Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 15

Workplace Belonging of Women Healthcare Professionals Relates to Likelihood of Leaving

Authors Schaechter JD , Goldstein R , Zafonte RD, Silver JK

Received 15 August 2023

Accepted for publication 29 September 2023

Published 26 October 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 273—284

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S431157

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Pavani Rangachari

Judith D Schaechter,1,2 Richard Goldstein,1 Ross D Zafonte,1– 4 Julie K Silver1– 4

1Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Charlestown, MA, USA; 3Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 4Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Correspondence: Julie K Silver, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, 300 1st Ave, Charlestown, MA, 02129, USA, Tel +1 617-952-5000, Fax +1 508-718-4036, Email [email protected]

Purpose: There is a high rate of attrition of professionals from healthcare institutions, which threatens the economic viability of these institutions and the quality of care they provide to patients. Women professionals face particular challenges that may lower their sense of belonging in the healthcare workplace. We sought to test the hypothesis that workplace belonging of women healthcare professionals relates to the likelihood that they expect to leave their institution.

Methods: Participants of a continuing education course on women’s leadership skills in health care completed a survey about their experiences of belonging in workplace and their likelihood of leaving that institution within the next 2 years. An association between workplace belonging (measured by the cumulative number of belonging factors experienced, scale 0– 10) and likelihood of leaving (measured on a 5-point Likert scale) was evaluated using ordinal logistic regression. The relative importance of workplace belonging factors in predicting the likelihood of leaving was assessed using dominance analysis.

Results: Ninety-nine percent of survey participants were women, and 63% were clinicians. Sixty-one percent of participants reported at least a slight likelihood of leaving their healthcare institution within the next 2 years. Greater workplace belonging was found to be associated with a significant reduction in the reported likelihood of leaving their institution after accounting for the number of years having worked in their current institution, underrepresented minority status, and the interaction between the latter two covariates. The workplace belonging factor found to be most important in predicting the likelihood of leaving was the belief that there was an opportunity to thrive professionally in the institution. Belonging factors involving feeling able to freely share thoughts and opinions were also found to be of relatively high importance in predicting the likelihood of leaving.

Conclusion: Greater workplace belonging was found to relate significantly to a reduced likelihood of leaving their institution within the next 2 years. Our findings suggest that leaders of healthcare organizations might reduce attrition of women by fostering workplace belonging with particular attention to empowering professional thriving and creating a culture that values open communication.

Keywords: gender equity, diversity, turnover, retention, healthcare workforce, thriving

Introduction

Healthcare institutions have long struggled with retention of their physicians, nurses and other professionals essential for direct patient care. The rate of attrition prior to the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported to be 5–10% annually for physicians1,2 and 16% annually for nurses.3 The pandemic brought on a record-high efflux of healthcare professionals from their workplaces.3–5 While pandemic-level attrition rates have since declined some, recent surveys found that 25–50% of healthcare professionals intend to leave their workplace within the next few years,6–8 suggesting that healthcare institutions may face persistently high rates of attrition.

The costs of attrition of healthcare professionals from their workplaces are substantial. The direct cost of recruiting and training new clinicians is high – estimated to be $250,000-$1,000,000 per physician depending on specialty and experience and $50,000 per nurse.3,9 There are also indirect costs of turnover, including disruptive impacts on patients, reduced productivity of the clinical team, and added burden on professionals who remain in the institution.2,10,11 Attrition of faculty scholars from academic healthcare institutions can reduce grant dollars coming into the organization as well as diminish the organization’s contribution to healthcare sciences and the caliber of its intellectual environment. The collective cost of attrition of healthcare professionals threatens the economic viability of the institutions and the quality of patient care provided.

Several factors lead healthcare professionals to leave their institution, including burnout,12 seeking a more favorable workplace culture,13 and pursuing an opportunity for career advancement.14 Women healthcare professionals experience higher rates of burnout,15 bear a greater fraction of family responsibilities,16–18 and face more barriers to career advancement19,20 than their counterparts who are men. These gender disparities may elevate women’s risk of leaving their healthcare institutions.21–24 Women who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM; ie, racial, ethnic, sexual orientation or gender identity minority) face additional challenges in their workplace that may magnify their risk of leaving.25,26 Given the challenges faced by women healthcare professionals, there is a need for institutional leaders to better understand the experiences of women in order to develop strategies that improve their retention.

The sense of belonging has long been understood to be a fundamental human need.27,28 A definition of belonging is the sense that “everyone is treated and feels like a full member of the larger community and can thrive.”29 A wealth of literature has demonstrated that a stable sense of belonging, which is an integral aspect of social safety, has substantial psychological and physical health benefits, and conversely that a perceived lack of belonging has detrimental effects on health.30

Belonging has been increasingly recognized as critical to a positive workplace environment.31–34 The experience of belonging in the workplace involves numerous dimensions including interpersonal connections with colleagues, feeling supported to do your best work, feeling valued and appropriately rewarded for your work, and believing that your personal values align with the mission of the institution.31,35 An eroded sense of belonging has been suggested to be a strong aversive psychological experience and thereby a key risk factor of attrition.36–38 Women healthcare professionals have reported an eroded sense of belonging due to challenges in their workplaces (eg, microaggressions, slowed career advancement, and sub-optimal family-friendly policies).39–43 To our knowledge, however, a link between workplace belonging and attrition risk in women healthcare professionals has not been studied previously. As workplace belonging emerges from a broad range of experiences in the institution (eg, interpersonal relationships, comfort with institutional culture and policies), the current study conceived of workplace belonging as the cumulative experience across multiple dimensions of belonging. The primary aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that women healthcare professionals will report a reduced likelihood of leaving their workplace within 2 years in association with a greater cumulative experience of workplace belonging. Secondarily, we aimed to identify workplace belonging factors that are particularly important in predicting the likelihood of leaving reported by women healthcare professionals.

Methods

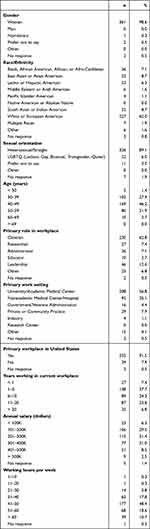

Using a sample of convenience, we surveyed attendees of a continuing education course on women’s leadership skills in healthcare was held virtually November 3–5 of 2022. The course was geared to healthcare professionals, including clinicians, researchers, and administrators, and was open to persons residing in all countries and all gender identities. All course attendees were invited to participate in the online survey via an introductory email sent by the office of continuing education on November 2 and a reminder email sent by the office on November 6. Attendees were also reminded verbally by the course director (JKS) about the survey once per day for the duration of the course. The online survey was implemented using Microsoft Forms (Microsoft 365), and the data were output in a Microsoft Excel file. Survey participants responded voluntarily and all survey responses were anonymous. Of the 856 course attendees, 366 completed the survey (43%). The study was deemed not human subjects research by the Mass General Brigham Research Office. Demographics of survey participants are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographics of Survey Participants (N = 366) |

The survey queried course participants about workplace belonging. A 10-item belonging instrument was created based on themes identified from a review of existing literature and instruments on workplace belonging, organizational culture, workplace engagement, and diversity and equity.35,44–48 We crafted the instrument to measure workplace belonging in the context of professionals working in healthcare organizations. We piloted the belonging instrument on colleagues who would not be attending the course and refined it based on feedback. Participants were asked to select all belonging factors they were experiencing in their current workplace (Table 2). The statement, “I am not experiencing any aspect of belonging listed above” was also available for selection. For each participant, the cumulative experience of workplace belonging was measured by the number of belonging factors selected, with 0 given for selecting “not experiencing any aspect of belonging” (scale 0–10).

|

Table 2 Survey on Belonging and Likelihood of Leaving |

The survey also queried course participants about the likelihood of leaving their current healthcare institution within 2 years, a time period used in previous large-scale surveys administered to physicians49–51 and academic medicine faculty,14,52 professionals who are comparable to our survey participants. Response options were on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “not likely” to “extremely likely” (scale 1–5, Table 2).

Several demographic characteristics were queried. A subset of these demographic data (ie, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity) was used to classify each participant as a URM or non-URM. URM was defined as any non-majority race/ethnicity (ie, not “White or European American”), sexual orientation (ie, not “heterosexual/straight”), or gender identity (ie, not a “woman” or “man”). Note that we asked participants about gender identity (ie, sense of self related to social and cultural expectations)53 rather than biological sex (ie, related to anatomical and physiological traits) because we presumed the former to be more closely linked to belonging, which is also rooted in a social context.54

Statistical tests were performed using Stata software (version 18, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Reliability of the 10-item belonging instrument was assesses using Cronbach’s α.55 The primary hypothesis that the cumulative experience of workplace belonging was associated with likelihood of leaving was tested using ordinal logistic regression. Several models that included the primary variable of interest (cumulative workplace belonging), one or more covariates (ie, URM status, age, and years in the current workplace), and their interactions were fitted. For each model, the estimated odds ratio (OR) with the 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were computed for each variable. Significance of the p-value was set at the two-sided 0.05 level. The significance of a combined set of covariates was tested using Wald χ2. Model selection was based on goodness-of-fit using Akaike information criteria, test of the proportional odds assumption, and parsimony.

Two approaches were used to identify workplace belonging factors particularly important in predicting the likelihood of leaving. First, the final model was fitted after replacing the main variable of interest (cumulative workplace belonging) with the set of 10 belonging factors each coded as a binary indicator variable. Second, dominance analysis was used to rank the importance of each independent variable. Dominance analysis is a method for rank ordering the predictive usefulness of independent variables in a regression model.56 Given our main interest in ranking the belonging factors, we did post-hoc ranking that excluded any independent variable other than the belonging factors. To evaluate the sensitivity of ranking the belonging factors to changes in the regression model, dominance analysis was repeated using alternative models that added and/or removed predictors other than the belonging factors.

Results

The percentage of survey participants who identified as women was 99% (Table 1). Sixty-three percent of survey participants identified their primary role to be clinician. Forty-one percent of survey participants identified as a racial, ethnic, sexual orientation or gender identity minority and were thus classified as a URM.

The 10-item belonging instrument was found to have a Cronbach’s α of 0.84, which indicates good internal consistency.57

Figure 1A shows the frequency at which each of the 10 workplace belonging factors was experienced by survey participants. “Feeling valued by my colleagues” was experienced most frequently (70% of cohort) and “Believing that I am being treated equitably” was experienced least frequently (31% of cohort). Figure 1B shows the frequencies in the cumulative number of belonging factors experienced by participants, with three belonging factors experienced most frequently (23% of cohort).

Sixty-one percent of participants reported at least a slight likelihood of leaving their healthcare institution within 2 years (10% extremely likely, 8% very likely, 22% moderately likely, 21% slightly likely), and the remainder (39%) reported they were not likely to leave their workplace within 2 years.

The final regression model selected to test the hypothesis that the cumulative experience of workplace belonging was associated with the likelihood of leaving included four independent variables: “cumulative workplace belonging”, “URM status, “years working in current workplace”, and the interaction between “URM status” and “years working in current workplace.” Based on this model, the cumulative experience of workplace belonging was significantly associated with the reported likelihood of leaving, adjusting for covariates in the model (OR 0.68, CI 0.63–0.74; p < 0.0001; Figure 2A). This result means that for each unit increase in the number of belonging factors experienced (eg, one to two belonging factors), there was a 32% decrease in the odds of reporting a higher category of likelihood of leaving (eg, extremely likely relative to very likely). The likelihood of leaving was also found to be significantly associated with a set of three other covariates (ie, “URM status”, “years working in current workplace”, and their interaction) after adjusting for the cumulative experience of workplace belonging (χ2 p < 0.01, Figure 2B). Differences between URM and non-URM in the likelihood of leaving varied over years working in their institution, with URM notably reporting a lower likelihood of leaving than non-URM when employed for <1 year and >20 years.

To address the second aim of identifying workplace belonging factors that are particularly important in the likelihood of leaving reported by women healthcare professionals, we fitted the final regression model after replacing the “cumulative workplace belonging” variable with a set of 10 belonging factor variables. This analysis found that the odds in the likelihood of leaving was significantly reduced by experiencing the belonging factors “believing I can thrive professionally” (OR 0.40, CI 0.23–0.67; p < 0.001) and “having input into work-related policies” (OR 0.62, CI 0.39–1.00; p < 0.05) after adjusting for the eight other belonging factors, “URM status”, “years working in current workplace”, and the interaction between the latter two covariates.

We also addressed the second aim of identifying workplace belonging factors that are particularly important in predicting the likelihood of leaving using dominance analysis. The regression model used in this analysis treated the set of three covariates “URM status”, “years working in current workplace”, and their interaction as a single variable “set” given the aforementioned finding that this collective set of covariates was significantly associated with the likelihood of leaving. Considering the belonging factors only, dominance analysis ranked “believing I can thrive professionally”, “having input into work-related policies”, and “feeling psychologically safe” as the first, second, and third most important predictors, respectively (Table 3). The belonging factor “feeling valued by my colleagues” ranked least important in predicting the likelihood of leaving. To evaluate the sensitivity of ranking the belonging factors to changes in the regression model, dominance analysis was repeated using three alternative models: 1) adding the predictor “cumulative workplace belonging”; 2) removing the predictor “set” and adding the predictor “cumulative workplace belonging”; and 3) removing the predictor “set.” Dominance analysis of the base model and the three alternative models consistently ranked the belonging factor “believing I can thrive professionally” as the most important and “feeling valued by my colleagues” as the least important among the 10 belonging factors in predicting the likelihood of leaving, indicating robustness of these two rankings. “Having input into work-related policies” and “feeling psychologically safe” ranked among the top three belonging factors in the base model and ranked among the top four in the alternative models, indicating confidence that these two belonging factors are moderately important in predicting the likelihood of leaving relative to all 10 belonging factors.

|

Table 3 Ranking of Predictors by Dominance Analysis |

Discussion

Women healthcare professionals often face challenges in their workplace (eg, burnout, slow advancement, microaggressions, and competing work-life demands) that erode their sense of workplace belonging.39–42 Women physicians21,24 and women in academic medicine23 have also been shown to have an elevated risk of attrition from their healthcare institution compared to their counterparts who are men. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the multidimensional experience of workplace belonging among women healthcare professionals in relation to their likelihood of leaving their institution. The main finding was that an increase in the cumulative number of workplace belonging experiences was associated with a significant reduction in reported likelihood of leaving within the next 2 years (Figure 2A). Self-reported likelihood of leaving of healthcare professionals has been shown to be a strong predictor of actual departure from the institution in the next two to five years.9,58,59 Accordingly, our result points to the cumulative experience of workplace belonging across multiple dimensions, including interpersonal relationships and comfort with organizational culture and policies, as a key factor affecting retention of women in their institutions. This finding is consistent with the growing body of literature demonstrating that the perceptions of healthcare professionals about their workplace – such as engagement,60,61 trust,62 and organizational factors13,63–65 - relate to retention. As workplace belonging can be understood as emerging from felt experiences of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the organization, our finding suggests that organizational DEI efforts may lead to a sense of belonging, which in turn may improve retention of women healthcare professionals.

Among the 10 workplace belonging factors available for selection, we found that “believing I can thrive professionally” was particularly important in the likelihood of leaving. Regression analysis found this belonging factor to be significantly associated with the likelihood of leaving after accounting for experiencing the other belonging factors. Dominance analysis consistently ranked this belonging factor as the most important predictor among all 10 belonging factors (Table 3). The concept of professional thriving has been described as involving intrapersonal factors (resilience, love of work), interpersonal factors (relationships with patients and colleagues), and institutional factors (support from leadership, team-spirited workplace, value-oriented practice, agency in the workplace).66,67 These factors of thriving overlap substantially with the multidimensional experience of workplace belonging. Accordingly, professional thriving might have been found to be the most important belonging factor for predicting the likelihood of leaving because its scope was broader than any of the other belonging factors available for selection and aligned closely with the cumulative experience of workplace belonging. The intent of clinicians to leave their institution in the next 2 years has been shown to be reduced, albeit modestly, by interventions aimed at improving communication within the workplace or improving workflow.68 Our findings raise the possibility that interventions targeting the multidimensional experience of workplace belonging might be effective in reducing the likelihood that women healthcare professional leave their institutions.

Among the other workplace belonging factors available for survey participants to select, “feeling psychologically safe” and “having input into work-related policies” were found to strongly influence their reported likelihood of leaving (Table 3). Psychological safety in the workplace has been defined as the belief that one can express personal ideas and concerns, ask questions, and admit mistakes without fear of negative consequences in the workplace.69 “Having input into work-related policies” indicates feeling that one’s thoughts and opinions have an impact in the workplace. The relative importance of these two belonging factors suggests that a workplace environment in which thoughts, opinions and ideas are valued may lead to improved retention of women healthcare professionals.

We found that URM status affected likelihood of leaving differentially over the number of years working in the current workplace. Most notably, URM women reported a lower likelihood of leaving than non-URM women when employed in their current workplace for <1 year and >20 years after adjusting for the cumulative experience of belonging (Figure 2B). A previous study found that women in academic medicine who identified as Black or “other” reported lower intent to remain (ie, equivalent to higher likelihood of leaving) in their institution than women who identified as White.70 Our study suggests that the likelihood of URM women leaving (or remaining) depends on years working in the healthcare institution and the experience of workplace belonging.

Our study has limitations. First, survey participants were attendees of a course on women’s leadership skills in health care and therefore results may not generalize well to women healthcare professionals who do not share a strong aspiration for a leadership position. Second, the belonging section of the survey used a check-all format. This format has been suggested to limit survey participants from thinking deeply about each item available for selection and increase the tendency to select the first option presented.71 Indeed, we did observe that the first belonging factor on the list (ie, “feeling valued by my colleagues”) was most frequently checked-off when only one belonging factor was selected (4.6% of cohort) and among all belonging factors (70% of cohort) (Figure 1A). The increased tendency to select the first belonging factor may explain why it ranked the least important belonging factor in predicting the likelihood of leaving (Table 3). The value of the check-all format has been shown to be its time-efficiency.71 Our use of this format allowed us to collect relatively detailed information about participants’ sense of workplace belonging in a relatively short period of time, which in turn enabled us to examine both the cumulative experience of workplace belonging and relative importance of belonging factors.

Conclusion

This study found that an increase in cumulative workplace belonging involving a broad range of experiences (eg, interpersonal relationships, comfort with institutional culture and policies) reduced the reported likelihood that women healthcare professionals would leave their institution within the next 2 years. The experience of professional thriving and feeling that one’s thoughts, opinions, and ideas are valued were found to be particularly important in women’s expected likelihood of leaving. These findings lay the groundwork for testing whether interventions that strengthen workplace belonging, with an emphasis on empowering professional thriving and improving open communication, improves retention of women in healthcare institutions.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR002541) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. Unrelated to this work, Dr Silver disclosed participating in funded research on culinary medicine, cancer prehabilitation, and chronic pain, as well as being a venture partner at Third Culture Capital. Dr Zafonte reported receiving personal fees from Springer/Demos, serving on scientific advisory boards for Myomo and OnCare, and receiving grants from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard, which was funded in part by the National Football League Players Association.

References

1. Association of American Medical College. Retention of Full-Time Clinical M.D. Faculty at U.S. Medical Schools. 11; 2011. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/analysis-brief/report/retention-full-time-clinical-md-faculty-us-medical-schools.

2. Schloss EP, Flanagan DM, Culler CL, Wright AL. Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):32–36. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906dff

3. NSI Nursing Solutions. NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report; 2023. Available from: www.nsinursingsolutions.com.

4. Frogner BK, Dill JS. Tracking turnover among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(4):e220371. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0371

5. Johnson KV, Boston-Fleischhauer C, Duke-Mosier S Staff turnover: 4 key takeaways from Advisory Board’s survey of 224 hospitals; 2022. Available from: https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2022/03/09/hospital-turnover-survey.

6. Bork RH, Robins M, Schaffer K, Leider JP, Castrucci BC. Workplace perceptions and experiences related to COVID-19 response efforts among public health workers — public health workforce interests and needs survey, United States, September 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(29):920–924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7129a3

7. Elsevier Health. Clinician of the Future Report 2022. Available from: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/clinician-of-the-future.

8. Massachusetts Medical Society. Supporting MMS Physicians’ Well-being Report: recommendations to Address the On-going Crisis; 2023. Available from: https://www.massmed.org/Publications/Research,-Studies,-and-Reports/Supporting-MMS-Physicians--Well-being-Report---Recommendations-to-Address-the-Ongoing-Crisis/.

9. Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z

10. Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–766. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4011-4

11. Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(1):2–7. doi:10.1097/00004010-200401000-00002

12. Linzer M, Jin JO, Shah P, et al. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(11):e224163. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4163

13. Sood A, Rishel Brakey H, Myers O, et al. Exiting medicine faculty want the organizational culture and climate to change. Chron Mentor Coach. 2020;4(SI13):359–364. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.12.011

14. Zimmermann EM, Mramba LK, Gregoire H, Dandar V, Limacher MC, Good ML. Characteristics of faculty at risk of leaving their medical schools: an analysis of the StandPoint Faculty Engagement Survey. J Healthc Leadersh. 2020;12:1–10. doi:10.2147/JHL.S225291

15. Rotenstein L, Harry E, Wickner P, et al. Contributors to gender differences in burnout and professional fulfillment: a survey of physician faculty. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(11):723–730. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.08.002

16. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(7):532–538. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00004

17. Matulevicius SA, Kho KA, Reisch J, Yin H. Academic medicine faculty perceptions of work-life balance before and since the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113539. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13539

18. Mody L, Griffith KA, Jones RD, Stewart A, Ubel PA, Jagsi R. Gender differences in work-family conflict experiences of faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):280–282. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06559-7

19. Richter KP, Clark L, Wick JA, et al. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2148–2157. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1916935

20. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694–1699. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146

21. Lall MD, Perman SM, Garg N, et al. Intention to leave emergency medicine: mid-career women are at increased risk. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1131–1139. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.5.47313

22. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. 2019. doi:10.31478/201905a

23. Brod HC, Lemeshow S, Binkley PF. Determinants of faculty departure in an academic medical center: a time to event analysis. Am J Med. 2017;130(4):488–493.

24. Chen YW, Orlas C, Kim T, Chang DC, Kelleher CM. Workforce attrition among male and female physicians working in US academic hospitals, 2014-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323872. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23872

25. Kaplan SE, Raj A, Carr PL, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):616–622. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001968

26. Cech EA, Waidzunas TJ. Systemic inequalities for LGBTQ professionals in STEM. Sci Adv. 2021;7(3):eabe0933. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe0933

27. Maslow AH. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

28. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

29. Harvard University Office for Equity, Diversity, Inclusion & Belonging. Definition of Belonging. Available from: https://edib.harvard.edu/files/dib/files/dib_glossary.pdf.

30. Slavich GM. Social safety theory: a biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020;16(1):265–295. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045159

31. Center for Talent Innovation. The Power of Belonging: What It Is and Why It Matters in Today’s Workplace; 2020. Available from: https://coqual.org/reports/the-power-of-belonging.

32. Gordon D, Achuck K, Kempner D, Jaffe R, Papanagnou D. Toward unity and inclusion in the clinical workplace: an evaluation of healthcare workforce belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29454. doi:10.7759/cureus.29454

33. Carr EW, Reece A, Kellerman GR, Robichaux A. The Value of Belonging at Work; 2019. Available from: https://hbr.org/2019/12/the-value-of-belonging-at-work.

34. Waller L. Fostering a sense of belonging in the workplace: enhancing well-being and a positive and coherent sense of self. In: Dhiman SK, editor. The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Well-Being. Springer International Publishing; 2021:341–367.

35. Jena LK, Pradhan S. Conceptualizing and validating workplace belongingness scale. J Organ Change Manag. 2018;31(2):451–462. doi:10.1108/JOCM-05-2017-0195

36. Salles A, Wright RC, Milam L, et al. Social belonging as a predictor of surgical resident well-being and attrition. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):370–377. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.08.022

37. Reinhardt AC, Leon TG, Amatya A. Why nurses stay: analysis of the registered nurse workforce and the relationship to work environments. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;55:151316. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151316

38. Stevens SM, Ruberton PM, Smyth JM, Cohen GL, Purdie Greenaway V, Cook JE. A latent class analysis approach to the identification of doctoral students at risk of attrition. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280325. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280325

39. Pololi LH, Jones SJ. Women faculty: an analysis of their experiences in academic medicine and their coping strategies. Gend Med. 2010;7(5):438–450. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2010.09.006

40. Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, Dottolo AL, Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):201–207. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1

41. Haggins AN. To be seen, heard, and valued: strategies to promote a sense of belonging for women and underrepresented in medicine physicians. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1507–1510. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003553

42. Lin MP, Lall MD, Samuels-Kalow M, et al. Impact of a women-focused professional organization on academic retention and advancement: perceptions from a qualitative study. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(3):303–316. doi:10.1111/acem.13699

43. Cochran A, Neumayer LA, Elder WB. Barriers to careers identified by women in academic surgery: a grounded theory model. Am J Surg. 2019;218(4):780–785. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.07.015

44. Carapinha R, McCracken CM, Warner ET, Hill EV, Reede JY. Organizational context and female faculty’s perception of the climate for women in academic medicine. J Womens Health. 2017;26(5):549–559. doi:10.1089/jwh.2016.6020

45. Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28–36, W6–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006

46. Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: the diversity engagement survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1675–1683. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000921

47. Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):859–869. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18

48. Thompson-Burdine JA, Telem DA, Waljee JF, et al. Defining barriers and facilitators to advancement for women in academic surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e1910228. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10228

49. Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Satele D, Balch C. Why do surgeons consider leaving practice? J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):421–422. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.11.006

50. Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(11):1625–1635. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.017

51. Mete M, Goldman C, Shanafelt T, Marchalik D. Impact of leadership behaviour on physician well-being, burnout, professional fulfilment and intent to leave: a multicentre cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e057554. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057554

52. Pollart SM, Novielli KD, Brubaker L, et al. Time well spent: the association between time and effort allocation and intent to leave among clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):365–371. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000458

53. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2022 doi:10.17226/26424..

54. Allen KA, Kern ML, Rozek CS, McInereney D, Slavich GM. Belonging: a review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Aust J Psychol. 2021;73(1):87–102. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

55. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

56. Luchman JN. Relative importance analysis with multicategory dependent variables: an extension and review of best practices. Org Res Methods. 2014;17(4):452–471. doi:10.1177/1094428114544509

57. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–55. doi:10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

58. Hann M, Reeves D, Sibbald B. Relationships between job satisfaction, intentions to leave family practice and actually leaving among family physicians in England. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(4):499–503. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq005

59. Degen C, Li J, Angerer P. Physicians’ intention to leave direct patient care: an integrative review. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):74. doi:10.1186/s12960-015-0068-5

60. Association of American Medical College. Promising Practices for Promoting Faculty Engagement and Retention in U.S. Medical Schools; 2017. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/standpoint-surveys/promising-practices.

61. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

62. Linzer M, Poplau S, Prasad K, et al. Characteristics of health care organizations associated with clinician trust: results from the healthy work place study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196201. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6201

63. Sancheznieto F, Byars-Winston A. Value, support, and advancement: an organization’s role in faculty career intentions in academic medicine. J Healthc Leadersh. 2021;13:267–277. doi:10.2147/JHL.S334838

64. Ellinas EH, Fouad N, Byars-Winston A. Women and the decision to leave, linger, or lean in: predictors of intent to leave and aspirations to leadership and advancement in academic medicine. J Womens Health. 2018;27(3):324–332. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6457

65. Dousin O, Collins N, Bartram T, Stanton P. The relationship between work-life balance, the need for achievement, and intention to leave: mixed-method study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(3):1478–1489. doi:10.1111/jan.14724

66. Gielissen KA, Taylor EP, Vermette D, Doolittle B. Thriving among primary care physicians: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(12):3759–3765. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06883-6

67. Kase J, Doolittle B. Job and life satisfaction among emergency physicians: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0279425. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279425

68. Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105–1111. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4

69. Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999

70. Onumah C, Wikstrom S, Valencia V, Cioletti A. What women need: a study of institutional factors and women faculty’s intent to remain in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2039–2047. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06771-z

71. Smyth JD, Dillman DA, Christian LM, Stern MJ. Comparing check-all and forced-choice question formats in web surveys. Public Opin Q. 2006;70(1):66–77. doi:10.1093/poq/nfj007

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.