Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

Unveiling the Paradox of Selflessness: Exploring Perceptions of Hypocrisy and Priority Outgroup in Intergroup Moral Dilemmas

Received 2 December 2023

Accepted for publication 14 March 2024

Published 20 March 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 1295—1311

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S452940

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Danni Yang, Xianyou He

Center for Studies of Psychological Application, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xianyou He, School of Psychology, South China Normal University, No. 55, West of Zhongshan Avenue, Tianhe District, Guangzhou, 510631, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study examines the impact of prioritizing the out-group in intergroup moral dilemmas. The research aims to achieve three primary objectives: 1) investigating the relationship between out-group prioritization and perceptions of hypocrisy, 2) exploring the influence of perceived hypocrisy and negative emotions on moral judgments, and 3) uncovering the underlying reasons for perceiving outgroup prioritization as hypocritical.

Methods: Experiments 1, 2 and 3 involved presenting Chinese participants with out-group rescuers and in-group rescuers and asking them to rate the two on three dimensions: level of hypocrisy, level of morality, and negative emotions toward the rescuers. In Experiment 3, the degree of similarity between participants and rescuers was manipulated to control for the level at which participants projected their own intrinsic motivations (ie, self-interest) onto the rescuers.

Results: Experiments 1 and 2 jointly showed that participants perceived the out-group rescuer as more hypocritical and immoral compared to the in-group rescuer, and that participants had stronger negative emotions toward the out-group rescuer. Mediation analysis also demonstrated that the perception of hypocrisy and negative emotions largely mediated the relationship between the different rescuers and participants’ evaluation of the rescuers’ morality. In Experiment 3, participants gave higher hypocrisy ratings to high projection out-group rescuers compared to low projection out-group rescuers.

Conclusion: In intergroup dilemmas, choosing to sacrifice the in-group to rescue the outgroup is perceived as more hypocritical, immoral, and objectionable. Perceived hypocrisy arises from an incongruity between individuals’ subjective judgments of the rescuers’ self-interest motives and the altruistic choice made by the rescuers to rescue the out-group.

Keywords: intergroup moral dilemmas, hypocrisy perception, negative emotions

Introduction

McManus, Kleiman-Weiner, Young1 have discussed the renowned altruist Peter Singer, whose philosophical stance argues for equal valuation of both our loved ones and strangers from afar. Singer’s commitment to his beliefs is demonstrated by his practice of donating 40% of his income to highly effective charities benefiting strangers. However, when faced with his mother’s Alzheimer’s disease, Singer deviated from his philosophy and allocated more resources to care for her than his moral argument would permit. Interestingly, Singer did not face criticism for this disparity, prompting our inquiry into the potential consequences had he adhered strictly to his philosophical principles.

Previous studies have explored the subsequent effects of the behavior of “sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group”. However, current research in this area remains limited, with only preliminary explorations in terms of social acceptability and the impulse to punish. McManus, Kleiman-Weiner, and Young (2020) conducted a study that found helping socially out-group individuals at the expense of helping close individuals was considered morally unacceptable Law, Campbell, Gaesser2 conducted a study that yielded similar results, indicating that individuals who prioritized the rescue of strangers over their own relatives were perceived as failing to uphold their familial obligations and consequently faced condemnation. However, a persistent question in the realm of research remains unanswered: why is the act of prioritizing assistance towards an external group in an intergroup dilemma considered morally unacceptable or even condemned, despite its highly altruistic nature? We acknowledge that there are numerous intricate factors at play, such as individuals’ failure to fulfill their responsibilities towards their own in-group when prioritizing assistance to an out-group.2 In our previous investigations into people’s general moral preferences in intergroup moral dilemmas, we found it fascinating that individuals, when asked about their preference for rescuing in-groups over out-groups, often cited the prioritization of strangers over their own relatives as an act of “hypocrisy”. This intriguing finding sparked our interest in exploring the concept of hypocrisy as an accurate descriptor for the perception of individuals who sacrifice the out-group at the expense of the in-group in intergroup dilemmas, whom we refer to as “out-group rescuers”.

In this article, our objective is to test this hypothesis by examining various types of intergroup moral dilemmas and assessing the role of perceiving hypocrisy in elucidating people’s negative moral evaluations of “out-group rescuers”. Furthermore, to illuminate this phenomenon, the present study integrates self-interest theory and social projection theory.3–7 Through the integration of these two theories, this study posits that during intergroup dilemmas, individuals not only speculate that others in society act in their own self-interest (prioritizing the in-group),8–10 but also project this belief onto others. However, when others make decisions contrary to their expectations (prioritizing the out-group), individuals are unwilling to acknowledge the fallacy of their initial expectations. Instead, they strive to maintain logical self-consistency by distorting the true intentions of others.7 They hold the belief that the other person prefers to prioritize the in-group but, due to certain factors (such as preserving a positive reputation), ends up behaviorally prioritizing the out-group. This internal/external inconsistency serves as the underlying source of the perception of hypocrisy”.

The present study holds significant theoretical implications as it offers valuable insights into individual attitudes in intergroup moral dilemmas and provides novel explanations for the negative moral evaluations directed at “out-group rescuers”. In addition, by integrating self-interest and social projection theories, this study contributes to the existing literature on moral psychology by presenting a comprehensive framework that unveils the underlying mechanisms shaping hypocritical evaluations. Moreover, this study holds practical significance as it sheds light on the generally unfavorable public attitude towards “out-group rescuers” and highlights the association between this attitude and perceived hypocrisy. The reasons for individuals’ aversion to “out-group rescuers” are often challenging to articulate, and a thorough examination of the psychological mechanisms involved can facilitate introspection and reduce prejudice against individuals who exhibit high ethical standards.

Hypocrisy

This study presents a novel investigation into the perception of hypocrisy among individuals who prioritize the interests of the out-group over the in-group. Hypocrisy, extensively studied by Batson, Kobrynowicz, Dinnerstein, Kampf, Wilson11, Batson, Thompson, Seuferling, Whitney, Strongman12, Batson, Thompson, Chen,13 refers to individuals who profess to uphold moral principles but act in ways that prioritize their self-interest. People’s aversion to hypocrisy reflects their aversion to inconsistency,14 as demonstrated by Simons’ seminal paper that conceptualized hypocrisy as “inconsistency between words and deeds”.15,16 However, unlike previous research, our experiment focuses on understanding how bystanders form perceptions of hypocrisy rather than assessing the actual hypocritical behavior of the individual. We argue that people’s perceptions of hypocrisy in others may influenced by subjective assumptions.

To support this conjecture, we draw on self-interest theory and social projection theory. According to self-interest theory,8–10 individuals generally perceive others in society as more inclined to prioritize their own interests. This perception likely stems from their general observations and experiences of human selfishness.9,10 Social projection theory posits that individuals unconsciously project their views and beliefs onto others.3–6,17 Combining these two theories leads to the prediction that, faced with intergroup moral dilemmas, individuals expect others to prioritize the in-group’s interests, and choose to save the in-group at the expense of the out-group. However, witnessing others prioritize the out-group over the in-group creates a discrepancy between their expectation and observed behavior, leading to cognitive dissonance and expectation violation.7 How do people react when conflict arises? In such cases, individuals often distort and misinterpret the rescuer’s underlying motives,18–20 attributing negative intentions to them,21 rather than admitting their own misjudgment and refuting self-interest theories. Many studies support this tendency in people. Critcher, Dunning22 found that individuals cynically misrepresent the altruistic behavior of others to maintain a strong belief in the power of egoism when confronted with contradictory evidence. The “Worst Motive Fallacy” theory,23 similar to self-interest theory, suggests that individuals may have multiple motivations for a particular behavior, some of which are more commendable than others. When all other factors are equal, observers tend to attribute the most negative motive as the primary driving force behind an individual’s actions. Additionally, studies on implicit discrimination against those with high moral standards partially support the research hypothesis that people will misrepresent the motives of the highly moral. Minson and Monin23 suggest that individuals strongly adhering to moral ideals that are not widely accepted may experience “do-gooder derogation”. Prioritizing saving the out-group over saving the in-group can be interpreted as publicly condemning those who prioritize the latter, posing a threat to their moral standing.24–26 In response to this self-threat, individuals tend to devalue or avoid the source of the threat.27,28 Furthermore, Smith29 demonstrated that people derive pleasure from witnessing the misfortunes of morally superior individuals. Developmental psychology research has also shown that even children exhibit reduced preference for generous peers during social comparisons.30

In summary, the cognitive dissonance arising from an individual’s subjective projections and a rescuer’s real choices,7 coupled with a misinterpretation of the rescuer’s motives,18–20 may serve as the primary basis for an individual’s judgment of the out-group rescuer’s hypocrisy. Furthermore, prior research consistently demonstrates individuals’ tendency to project their own characteristics onto objects that bear greater resemblance to themselves.3,31 Therefore, if our hypothesis holds, in intergroup dilemmas, individuals will not only perceive those who prioritize rescuing out-groups as more hypocritical but will also assign higher hypocrisy ratings to those out-group rescuers who share greater similarity with themselves. This occurrence stems from the positive correlation between the level of similarity and the degree of social projection.3,31 As similarity increases, so does social projection, leading to heightened cognitive conflict and elevated ratings of hypocrisy by individuals.

Negative Emotion

A previous study by Laurent, Clark, Walker, and Wiseman32 examined the emotional responses elicited by hypocritical behavior. The study showed that perceptions of hypocrisy primarily evoke emotions of disgust and anger toward the hypocrite, consequently increasing the likelihood of punishing the hypocrite. An open question remains as to whether the emotional responses triggered by individuals’ subjective assumptions of hypocrisy in the present study are consistent with the broader emotional responses elicited by hypocrisy. Moreover, past research confirms the significant role of emotions in moral decision-making alongside conscious reasoning.33–36 It has been demonstrated that individuals rely more on intuitive processes than deliberate reasoning when making moral judgments, underscoring the importance of emotions in moral decision-making.37 Therefore, utilizing emotions as a link could concurrently connect hypocrisy perception and moral evaluation. We hypothesized a mediating pathway whereby an individual’s perception of out-group rescuer hypocrisy leads to the individual experiencing emotions of disgust and anger toward the out-group rescuer, ultimately resulting in a lower moral evaluation of the out-group rescuer. This mediating relationship may unveil the mechanisms underpinning individuals’ low moral evaluations of out-group rescuers.

The Present Experiment

The present study aimed to investigate whether individuals exhibit hypocritical judgments towards those who prioritize the out-group in intergroup dilemmas. Experiments 1 and 2 involved presenting participants with scenarios that depicted “sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group” and “sacrificing the out-group to save the in-group”, and asked them to make hypocritical evaluations of different rescuers. Our primary hypothesis was as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Participants will perceive rescuers who sacrifice the out-group in intergroup dilemmas as more hypocritical.

Furthermore, this study aimed to investigate the mediating role of hypocrisy perceptions in explaining participants’ moral evaluations of rescuers with different options. Given the potent negative emotions that may arise from perceptions of hypocrisy32 and the pivotal role of emotions in moral judgment,37 one of the primary research hypotheses of this experiment posits that instances of hypocrisy related to various rescuer choices inherently elicit negative emotions in individuals, which subsequently shape their moral judgments. We hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2: The perception of hypocrisy and the experience of negative emotions will function as chained mediating variables, effectively accounting for participants’ moral evaluations of various rescuers.

The primary objective of Experiment 3 was to examine the explanatory power of self-interest and social projection theories in understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying individuals’ perceptions of hypocrisy towards different rescuers. To accomplish this, we manipulated the ethnic background of the rescuers in the scenarios as Vietnamese and Africans. In this experiment, all participants were of Chinese ethnicity, which suggests a higher level of self-projection onto other Asian ethnicities, leading to the expectation that Vietnamese individuals would be more likely to prioritize rescuing the in-group. This also implies a higher level of cognitive conflict among participants when Vietnamese chose to prioritize rescuing the out-group. Based on this rationale, we propose the following expectations:

Hypothesis 3: Chinese participants’ hypocrisy ratings will be significantly higher for Vietnamese who sacrifice out-groups compared to Africans who sacrifice out-groups.

By investigating these hypotheses, we aim to gain insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying individuals’ perceptions of hypocrisy and how it relates to moral evaluations in intergroup dilemmas.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 aimed to investigate perceptions of hypocrisy in the context of intergroup dilemmas, specifically when confronted with different rescue choices. Participants were presented with scenarios in which a rescuer had the options of “sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group” and “sacrificing the out-group to save the in-group”, and were subsequently asked to assess the rescuer’s level of hypocrisy. Carrigan, Adlam, and Langdon38 have shown that the nature of rescue behaviors in intergroup dilemmas can influence individuals’ moral judgments. For instance, when faced with a choice between harming an in-group or an out-group object, people tend to prefer the in-group; when deciding which side to benefit, people also tend to favor the in-group. Furthermore, our previous research has found that an individual’s level of input in intergroup dilemmas affects their moral evaluations of different choices. Therefore, we considered these two variables in our experiment to better explore participants’ perceptions of hypocrisy towards the “out-group rescuers”.

Method

Ethical Issues

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained. The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the research program and applicable laws and regulations. Furthermore, the study adhered to the principles outlined in the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants and Design

A total of 141 Chinese participants (99 females, 42 males; aged 18 to 25) were recruited for the experiment. Prior to their participation, all participants were provided with comprehensive information about the voluntary nature of the experiment and the anonymity of their involvement. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of the experiment. The sample size was determined using a power analysis conducted with G*power software, indicating a minimum sample size of 76 participants to detect a small effect size (f = 0.025) with an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.95 (Fowler, Law, Gaesser.39 To compensate participants for their time and effort, a payment of 5 RMB was provided to each participant. It is important to note that the experiments were not pre-registered, which applies to all experiments conducted in this experiment. No data were omitted from the final data analysis.

Procedure

The experimental procedure was based on the work of Carrigan, Adlam, and Langdon38 and utilized a mixed design with 2 (Rescue Choice: Sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group; Sacrificing the out-group to save the in-group) * 2 (Nature of Behavior: Giving; Taking) * 2 (Monetary Value: Low; High). Rescue Choice and Monetary Value were manipulated as between-participants variables, while the Nature of Behavior was a within-participants variable.

The experimental process, as depicted in Figure 1, began with the display of a cross symbol on a black background for 500 milliseconds. Participants were then informed that they would act as observers in a team dictator game involving three individuals: Allocator A, A’s friend (recipient B), and a stranger (recipient C). Allocator A faced a moral dilemma where they had to decide whether to give or take a sum of money from either their friend B or the stranger C to advance the game, and A was told that the game would not continue until they had made a decision. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions: 2 (rescue choice: Sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group; Sacrificing the out-group to save the in-group) * 2 Monetary Value (Low; High). The monetary value was set at RMB 10 (approximately USD$1.5) for the low level and RMB 100 (approximately USD $15) for the high level. Within each condition, participants were presented with both the “giving” and “taking” scenarios which were presented in a randomized order. For example, in the Save Out-group + High Level + Take Condition, participants see that Allocator A chooses to take 100 RMB from their friend B. It is important to note that in the giving condition, choosing the in-group represents “saving the in-group” behavior, whereas choosing the out-group represents “saving the out-group” behavior. Conversely, in the taking condition, the opposite holds true: choosing the in-group signifies “saving the out-group”, while choosing the out-group represents “saving the in-group” behavior.

|

Figure 1 Specific procedure for Experiment 1. |

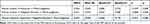

After each experimental condition was read, participants completed a survey where they evaluated Allocator A based on perceptions of hypocrisy. Detailed information about the scales used can be found in Table 1. The measurement scales ranged from 1 (extremely weak) to 7 (extremely strong). Participants underwent randomized testing sequences for both the “giving” and “taking” scenarios, completing all components of one condition before moving on to the next. Finally, they completed a questionnaire asking for demographic information including gender and age.

|

Table 1 Specific Measurements in Experiment 1 and 2 |

Results

Hypocrisy

The participant’s final hypocrisy score was derived by calculating the mean of questions 1 and 2 in Table 1. Through a repeated measures analysis of variance 2 (Rescue Choice: Sacrificing the ingroup to save the outgroup; Sacrificing the outgroup to save the ingroup) * 2 (Nature of Behavior: Giving; Taking) * 2 Monetary Value (Low; High), we investigated the phenomenon of hypocrisy in moral decision-making. Regarding the dimension of hypocrisy level, we found a significant interaction effect between behavioral nature and input level on hypocrisy ratings (see Figure 2A), F (1, 137) = 3.019, p = 0.085, ηp² = 0.022. Specifically, the difference in hypocrisy ratings between giving and taking behaviors was significant at the low monetary value level (giving M = 3.083, SD = 0.171; taking M = 3.596, SD = 0.191), but this difference disappeared at the high monetary value level. In addition, we observed a significant interaction effect between rescue choice and monetary value on hypocrisy ratings (see Figure 2B), F (1, 137) = 4.302, p = 0.040, ηp² = 0.030. In the “saving the out-group” condition, as monetary value increased, participants rated the hypocrisy of the rescuer higher (low level: M = 3.096, SD = 0.224; high level: M = 3.601, SD = 0.173, p = 0.077). Furthermore, we observed a significant main effect of behavioral nature, F (1, 137) = 4.938, p = 0.028, ηp² = 0.035. Participants rated the hypocrisy level of giving behavior (M = 3.19, SD = 0.129) significantly lower than that of taking behavior (M = 3.486, SD = 0.144).

Discussion

The findings from Experiment 1 provide initial support for the hypothesis that out-group rescuers are more likely to receive higher hypocrisy scores compared to in-group rescuers. However, it is important to acknowledge the presence of uncertainties associated with these results. Notably, participants displayed significantly elevated hypocrisy ratings for out-group rescuers only in the high monetary value condition. This suggests that the experimental manipulation might not have adequately elicited emotional responses from participants, given the relatively inconsequential impact of the Dictator game. Additionally, participants’ role as bystanders in the experiment may have dampened their emotional engagement.

Furthermore, we recognize concerns regarding the potential perception of hypocrisy ratings as a distortion of moral evaluations by participants. It is possible that participants did not use the same definition of hypocrisy and would benefit from being explicitly provided with a clear definition of hypocrisy before the rating process. To address these concerns and further explore the aforementioned issues, we conducted Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

The primary objective of Experiment 2 was to further examine the perception of hypocrisy among out-group rescuers in intergroup dilemmas and explore the mediating role of hypocrisy perceptions and the negative emotions triggered by these perceptions in relation to different rescue choices and moral evaluations. The general procedure of the experiment was similar to Experiment 1, with participants being presented with moral dilemmas and the choices made by rescuers and asked to evaluate the rescuers.

Several modifications were made to Experiment 2 from Experiment 1. Firstly, to enhance the emotional engagement of the participants, we increased the difficulty of the intergroup dilemma. Unlike Experiment 1, in which participants in the dictator game were not significantly affected by gaining or losing, Experiment 2 introduced a food crisis scenario that posed a substantial threat to the immediate interests of the out-group. This allowed us to investigate individuals’ attitudes towards out-group rescuers within a genuine moral dilemma relevant to social reality. Additionally, in order to assess participants’ moral evaluation and emotional arousal, we incorporated the moral evaluation and negative emotion scores as supplementary measures. Besides, to ensure a clear understanding of hypocrisy, we explicitly asked participants to define hypocrisy and provided a brief explanation of the distinction between hypocrisy and immorality during the experimental procedure.

Method

Participants and Design

In Experiment 2, we recruited a total of 170 Chinese participants, including 50 females and 120 males, with a mean age of 22.5 years (SD = 4.49). Before the experiment, each participant provided informed consent after receiving detailed information about the voluntary nature of their participation and the confidentiality of their data. The sample size was determined based on a power analysis conducted using G*Power software, which indicated that a sample of 18 participants would be sufficient to detect a small effect size (effect size f = 0.025) with an alpha level of 0.05 and statistical power of 0.95 (Fowler et al, 2021). To compensate participants for their time and effort, all individuals received a payment of 5 RMB. No data were omitted from the final data analysis.

Procedure

The procedure for Experiment 2 employed a within-participant design, following the methodology outlined in Fowler, Law, and Gaesser39 ‘s experiment. The design utilized a 4 (proximity object type: same nation, same city, friend, family member) x 3 (rescue choice: sacrificing out-group to save in-group; sacrificing in-group to save out-group; save without intergroup conflict) factorial design. The experiment involved presenting participants with 12 vignettes, each depicting a scenario related to global food shortages.

In each dilemma, the rescuer faced a moral dilemma involving two individuals suffering from hunger, representing in-group and out-group social targets. The out-group target was consistently someone from a far away country (African), while the ingroup target varied, including someone from the same country as the rescuer, someone from the same city, and a friend or family member of the rescuer.

At the outset of the experiment, participants were instructed to define hypocrisy and provide a brief description of the distinction between hypocrisy and immorality. We posed a straightforward question to participants regarding the disparity between immorality and hypocrisy, without further intervention. During the formal experimental procedure, participants observed the rescuer acquiring knowledge about global food shortages. Subsequently, they were presented with a scenario in which the rescuer had to make a decision between helping the in-group target, thereby sacrificing the out-group target, or helping the out-group target, thereby sacrificing the in-group target. The “saving without intergroup conflict” condition involved a single person seeking support, with the person’s identity consistent with the in-group object type, including the same country, city, friend, or family. In this condition, the rescuer only needed to weigh their own interests against those of the person seeking assistance, without any involvement of out-groups. This aimed to examine whether intergroup conflict of interest is a necessary condition for hypocrisy perception by comparing “saving without intergroup conflict” and “sacrificing in-group to save out-group”.

The specific variations among the 12 vignettes can be found in Table 2. At the end of each narrative, participants were asked to rate the rescuer’s level of hypocrisy, morality, as well as their own emotions (see Table 1 for specific questions). The order of presentation for the 12 vignettes was randomized. The trial materials were presented in Mandarin, with a translated version provided in Table 2. Finally, participants provided personal information such as gender and age.

|

Table 2 Specific Experimental Materials for the 16 (4 Ingroup Type × 3 Rescue Choice) Conditions in Experiment 2 |

Results

Moral Judgment and Negative Emotions

We conducted a 4 (proximity object type: same country, same city, friend, family member) × 3 (rescue choice: sacrificing out-group to save in-group; sacrificing in-group to save out-group; saving without intergroup conflict) repeated measures ANOVA on ratings of moral judgment and negative emotions. The participant’s final negative emotion score was derived by calculating the mean of questions 3 and 4 in Table 1.

The results revealed a significant main effect of rescue choice on moral judgment, F (2, 338) = 97.461, p = 0.000, ηp² = 0.366. Post-hoc analyses (see Figure 3) demonstrated significant differences between each pair of conditions (all p = 0.000). The rankings of moral evaluations for the three conditions, from lowest to highest, were sacrificing the ingroup to save the outgroup (M = 3.968, SD = 0.112), sacrificing the outgroup to save the ingroup (M = 5.162, SD = 0.097), and rescuing without intergroup conflict (M = 5.560, SD = 0.093).

Furthermore, there was a significant main effect of rescue choice on ratings of negative emotion (see Figure 3), F (2, 338) = 83.367, p = 0.000, ηp² = 0.330. Participants reported experiencing more negative emotions towards the rescue choice of sacrificing ingroup to save outgroup (M = 4.536, SD = 0.122) compared to sacrificing outgroup to save ingroup (M = 3.126, SD = 0.131, p = 0.000) and engaging in rescuing behavior without intergroup conflict (M = 2.943, SD = 0.137, p = 0.000). Additionally, the negative emotion scores for rescuing without intergroup conflict were significantly lower than those for sacrificing outgroup to save ingroup (p = 0.004).

Hypocrisy

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of 4 (proximity object type: same country, same city, friend, family member) × 3 (rescue choice: sacrificing outgroup to save ingroup; sacrificing ingroup to save outgroup; rescuing without intergroup conflict) on hypocrisy scores. The results revealed a significant main effect of rescue choice on hypocrisy judgment (see Figure 3), F (2, 338) = 80.727, p = 0.000, ηp² = 0.323. Participants’ hypocrisy ratings were significantly higher for rescuers who chose to save the out-group (M=4.28, SD=0.126) compared to those who chose to save the in-group (M=2.99, SD=0.131, p = 0.000), as well as for rescuers in the rescue without intergroup conflict condition compared to those who chose to save the ingroup (M=2.83, SD=0.134, p = 0.003). These findings provide empirical evidence supporting the existence of hypocritical perceptions in intergroup moral dilemmas, specifically related to the “outgroup rescuer”, consistent with hypothesis 1.

Furthermore, the hypocrisy score for the “rescuing without intergroup conflict” condition was found to be significantly lower than that for the “sacrificing in-group to save out-group” condition. The primary distinction between these two conditions lies in the presence or absence of intergroup dilemmas. This indicates that perceptions of hypocrisy are largely contingent on conflicts of interest between internal and external groups. Besides, neither the proximity object type, nor the interaction between proximity object type and rescue choice was significant.

Alternative Model

To rigorously investigate the validity of Hypothesis 2 and provide novel insights into the differentiation of attitudes towards distinct rescue choices, we employed a hypothesized path model (see Figure 4). Our experiment aimed to explore the relationship between rescue choices, moral judgment, perception of hypocrisy, and negative emotions. In our path model, we manipulated the rescue choices (in-group vs out-group) as a predictor of perceived hypocrisy. Additionally, we included experimental conditions, perceived hypocrisy, and negative emotions as predictors of participants’ moral judgments. Furthermore, we investigated the mediating role of hypocrisy ratings on negative emotions and moral judgments using bootstrapped mediation analyses with 5000 samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

|

Figure 4 Predicted association between Rescue Choice (Saving Out-Group, Saving In-Group) and Moral judgement through Perceptions of hypocrisy and negative emotions (examined in serial mediation models in Table 3). |

The results, as presented in Table 3, demonstrate significant direct effects of rescue choices on moral judgment, hypocrisy ratings, and negative emotions ratings. We also examined the indirect effects of rescue choices on hypocrisy ratings and negative emotion ratings, hypocrisy ratings on negative emotions and moral judgment, and negative emotions on moral judgment. All these groups of indirect effects were found to be statistically significant, with detailed values provided in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Mediator Models Predicting Moral Judgement of Different Rescue Choices from Hypocrisy Perception and Negative Emotions |

Specifically, our analyses revealed that perceived hypocrisy significantly accounted for a portion of variance (Indirect effect = 0.526, SE = 0.034, 95% CI [0.083, 0.216]) in moral judgment (see Table 4), supporting the assumed model pathway of rescue choices ➔ hypocrisy ➔ negative emotion ➔ moral judgment. Moreover, negative emotions were found to account for a significant proportion of variance (Indirect effect = 0.016, SE = 0.015, 95% CI [0.022, 0.080]) in moral judgment. These findings align with our initial hypotheses, indicating that manipulating rescue choices significantly predicts perceived hypocrisy, which in turn predicts negative emotions. Ultimately, negative emotions significantly influence moral evaluations (Indirect effect = 0.403, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.066, 0.176]).

|

Table 4 Tests of Serial Mediation Predicting Moral Judgement from Rescue Choice Through Hypocrisy Perception and Negative Emotions |

Discussion

The findings of Experiment 2 provide strong support for Hypothesis 1, confirming individuals’ tendency to perceive “out-group rescuers” as hypocritical. Additionally, Experiment 2 offers a novel explanation for the low moral evaluations of out-group rescuers. Specifically, the act of rescuing out-groups elicits hypocritical judgments, which subsequently trigger negative emotions such as aversion and anger. Ultimately, these negative emotions contribute to the formation of low moral evaluations.

Experiment 3

The primary aim of Experiment 3 was to explore the psychological mechanisms underlying individuals’ perceptions of hypocrisy in various rescue options, utilizing the framework of self-interest theory and social projection. In this experiment, participants were once again presented with an intergroup dilemma in which the rescuer had to choose between an in-group and an out-group. We hypothesized that individuals would rate the hypocrisy of out-group rescuers who shared higher levels of similarity to themselves as significantly higher than those with lower levels of similarity. Building upon previous findings demonstrating that greater object similarity leads to heightened levels of self-projection,4,31 we argued that the cognitive conflict perceived by participants when encountering out-group rescuers with high similarity would also be elevated, thus resulting in higher hypocrisy ratings.

To achieve this goal, we introduced two main characters from different ethnic backgrounds, specifically Vietnamese and African, and informed the participants of their respective countries of origin. All participants in our experiment were of Chinese origin, indicating a higher inclination to attribute their own characteristics to individuals of Vietnamese descent rather than those of African descent. We chose Vietnamese faces instead of Chinese faces in our study to mitigate potential biases that could arise from using Chinese faces in intergroup dilemmas. Including Chinese faces may enhance the self-relevance of the participants, leading them to unconsciously adopt an in-group perspective towards the rescuer, potentially impacting the reliability of the experimental results, which we aimed to avoid.

Furthermore, driven by self-interested inclinations, individuals are likely to project their own thinking of “priority in-group” onto Vietnamese. If Vietnamese exhibit choices of a “priority out-group” that conflict with participants’ expectations, we hypothesized that this incongruity would result in a significant increase in participants’ evaluations of hypocrisy towards the Vietnamese compared to the African rescuer.

By incorporating these elements, Experiment 3 aimed to provide further insights into the mechanisms that shape individuals’ perceptions of hypocrisy, as well as the role of self-interest and social projection in this cognitive process.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 71 Chinese participants (41 females, 30 males) with a mean age of 21.72 years (SD = 5.24) were recruited for this experiment. The sample size was determined using a G*Power analysis, which indicated that 49 participants would be sufficient to detect a small effect size (effect size f = 0.25, alpha = 0.05, power = 0.99) (Fowler et al, 2021). Participants were compensated with a payment of 5 RMB for their time and effort. No data were omitted from the final data analysis.

Procedure

This experiment employed a within-participant design with a 2 (rescue choice: sacrificing out-group to save in-group; sacrificing in-group to save out-group) * 2 (rescuer ethnicity: Vietnamese; African) factorial combination. Participants were presented with four vignettes featuring a rescuer (Vietnamese or African) facing an intergroup moral dilemma related to a global food shortage. In each vignette, the rescuer learned about two individuals in need of food, representing in-group and out-group objects, respectively. The rescuer had to decide whether to assist their friend (prioritizing in-group) or the suffering person in the other country (prioritizing out-group). The inclusion of rescuers from different ethnicities aimed to control the level of social projection participants had onto the rescuers, with the expectation that Chinese participants would project more onto Vietnamese than Africans due to greater cultural and ethnic similarities with the former group.

Similar to Experiment 2, participants were asked to define hypocrisy before the formal experiment began. The formal experiment consisted of two phases, as illustrated in Figure 5. The first phase was the social projection test, where participants were shown pictures of Vietnamese and African faces in random order. They were then instructed to rate the faces on 20 personality traits, with half being positive (eg, intelligent, resourceful, tolerant) and half negative (eg, aggressive, gullible, possessive). After evaluating the faces, participants rated themselves on the same personality traits using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strong nonconformity) to 7 (strong conformity). This approach aligns with established social projection scales.5

|

Figure 5 The specific procedure of experiment 3. |

The second phase consisted of the hypocrisy judgment task. Participants were initially informed about the global food crisis and subsequently presented with information regarding two individuals, namely a Vietnamese person and an African person, who were both facing the same moral dilemma. The image material was taken from a database of faces developed by Tottenham, Tanaka, Leon, McCarry, Nurse, Hare, Marcus, Westerlund, Casey, and Nelson.40 Participants were shown images of the rescuers’ faces along with descriptions of their respective moral dilemmas, as illustrated in Figure 6. After reviewing the materials, participants were first asked to indicate their own choices. Subsequently, they were instructed to rate the level of hypocrisy exhibited by the rescuers on a seven-point scale, based on the hypothetical scenario of the rescuer in the picture choosing to save either their friend or a person suffering in another country. The scale ranged from 1 (indicating “not at all hypocritical”) to 7 (indicating “very hypocritical”). The different rescue choices (sacrificing out-group to save in-group; sacrificing in-group to save out-group) and the characteristics of the rescuers (Vietnamese; African) were presented in a randomized order. Additionally, participants were requested to provide demographic information such as age and gender.

|

Figure 6 Moral Dilemma Experimental Materials Presentation Scenarios. |

Manipulation Check

To assess the extent of participants’ projection of traits onto Vietnamese compared to Africans in Experiment 3, a series of regression analyses were conducted. Separate regressions were performed to predict participants’ ratings of positive and negative traits for themselves based on their responses to Vietnamese and Africans, respectively. These regression analyses were used to calculate projection scores for each participant. The standardized beta weights from these regressions were utilized to measure a) the projection of positive traits and b) the projection of negative traits, following a similar procedure as described in Ames.4 This measure of projection captures the range from positive to negative projection, with higher mean beta values for positive traits indicating that participants attribute their self-perceived characteristics to the target object.

The results of the regression analyses indicated that participants’ ratings of positive and negative traits for themselves significantly predicted their ratings of positive and negative traits for Vietnamese: positive: ß = 0.884, t = 12.046, p = 0.000; negative: ß = 0.833, t = 12.046, p = 0.000. Similarly, participants’ ratings of positive and negative traits effectively predicted their ratings of positive and negative traits for Africans: positive: ß = 0.645, t = 5.745, p = 0.000; negative: ß = 0.686, t = 5.745, p = 0.000. However, it is evident that the Chinese participants exhibited higher levels of projection toward Vietnamese compared to Africans.

Furthermore, the experiment explored the prevalence of self-interested motivations in intergroup moral dilemmas. The findings revealed that a majority of participants (80.28%) prioritized the ingroup, while a minority (19.71%) prioritized the outgroup. These results provide evidence for the existence of self-interested motivational tendencies among individuals facing intergroup moral dilemmas.

Hypocrisy

In Experiment 3, the primary objective was to provide evidence for the unconscious projection of self-interested motives onto others, leading individuals to perceive them as hypocritical when their behavior is inconsistent with these motives. Hypothesis 3 was tested using a repeated measures ANOVA with a 2 (rescue choice: sacrificing out-group to save in-group; sacrificing in-group to save out-group) * 2 (rescuer type: Vietnamese vs African) design.

The analysis revealed a significant interaction between rescue choice and rescuer type on hypocrisy ratings, F (1, 70) = 4.143, p = 0.046, ηp² = 0.056 (as depicted in Figure 7). To further investigate this interaction, simple effects analyses were conducted. The results indicated that under the “sacrificing in-group to save out-group” condition, participants rated Vietnamese (M = 3.141, SD = 0.203) significantly higher in hypocrisy compared to Africans (M = 2.789, SD = 0.185, p = 0.019). Furthermore, the results revealed a significant main effect of rescue choice on hypocrisy ratings, F (1, 70) = 5.94, p = 0.017, ηp² = 0.078. Participants rated a person sacrificing in-group for out-group (M = 2.965, SD = 0.180) as significantly more hypocritical than a person making the opposite choice (M = 2.697, SD = 0.175).

|

Figure 7 The effect of rescue choice (saving out-group, saving in-group) and rescuer type (Vietnamese, African) on hypocrisy ratings (*p < 0.05). |

Discussion

In Experiment 3, our study aimed to explore the relationship between participants’ social projection of the rescuer and their perceptions of hypocrisy. The results consistently supported our hypothesis, demonstrating that perceiving others engaging in “saving out-group” actions led to a perception of hypocrisy. Specifically, participants perceived the highest levels of hypocrisy when those from socially projected groups, specifically Vietnamese, chose to save outgroup individuals. These findings provide support for Hypothesis 3, which suggests that participants’ perception of hypocrisy in the context of “saving out-group” is primarily influenced by the cognitive conflict between their subjective projection of self-interested motives and the selfless choices made by the people they had high self-projection onto. Consequently, participants perceived the rescuers as “hypocrites”.

General discussion

This study successfully validated the phenomenon of hypocritical judgments towards individuals who prioritize out-group rescue in intergroup dilemmas. Through the implementation of a mixed experimental design and a within-subjects experimental design across various intergroup dilemma contexts in Experiments 1 and 2, we obtained robust findings. Experiment 2 further enhanced our understanding by establishing a mediating chain that connects the choice to rescue, hypocritical perception, negative emotion, and moral evaluation. Specifically, our results demonstrate that hypocritical perceptions and resulting negative emotions contribute to the tendency to evaluate acts of “sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group” with low moral regard. Experiment 3 delved deeper into the underlying mechanism behind hypocritical perceptions towards out-group rescuers by considering the level of self-interested motivation projected onto different racial targets. The findings revealed that these perceptions arise due to a cognitive conflict between the perceived self-interested motivations of the perpetrator and the altruistic behaviors they ultimately exhibit.

The theoretical significance of this study lies in its novel contribution to the framework of intergroup moral dilemmas by introducing the concept of hypocrisy perception. Our findings indicate that individuals tend to perceive the conduct of “sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group” as hypocritical. This discovery provides a comprehensive explanation for the enduring controversy surrounding divergent moral evaluations of “prioritizing the out-group”. Individuals exhibit a dual perception of this behavior, considering it both morally virtuous and ethically commendable, while also experiencing repulsion towards the act and the individuals performing it.41–43 The role of hypocrisy perception and its subsequent unpleasant emotions holds significant implications within this context. Furthermore, this study challenges the conventional understanding of hypocrisy as solely an incongruity between an individuals’ words and actions. Instead, we propose that the perception of hypocrisy is contingent upon the observer rather than the actor. It hinges on the disparity between the observer’s interpretation of the actor’s inner thoughts and the actor’s actual demonstrated behaviors. This proposition opens new avenues for future research on hypocrisy, suggesting that the determination of hypocrisy is not solely contingent upon the actor’s genuine hypocritical nature but also on the inconsistency between the observer’s perceived thoughts and the actor’s exhibited behaviors. Consequently, even if an actor is not inherently hypocritical, the possibility of a hypocrisy judgment arises when there is inconsistency between the observer’s perceived thoughts and the actor’s exhibited behaviors.

The practical significance of this study is evident. Research has shown that individuals or entities perceived as hypocritical face moral condemnation, punitive emotions, and various forms of blame more than instances of mere unethical behavior.44 The unique nature of the act of “priority the out-group”, where the actor not only does not benefit but is also criticized for their good intentions, provides an important reference point for individuals’ decision-making processes and their efforts to maintain their moral standing within society.

As with all studies, there are limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn. Firstly, it is worth noting that this study only included participants from a Chinese cultural background, which raises uncertainty regarding the universality of the perceived hypocrisy associated with “prioritize the out-group” across cultures. To determine the universality of this perception, future studies should include participants from diverse cultural backgrounds to allow for cross-cultural comparisons.

Another concern that warrants consideration is the potential influence of our experimental prompts on participants’ responses. It is plausible that participants may have been primed to contemplate the hypocritical nature of rescuing the out-group, rather than independently forming their perception of such behavior. Thus, future research should strive to employ more objective measures to substantiate the conclusions drawn from this study.

Additionally, it is important to note that our study solely compared participants’ ratings of hypocrisy between those who prioritized rescuing the out-group and those who prioritized rescuing the in-group. Consequently, the results can only indicate that participants perceived individuals who prioritize out-group rescue as more hypocritical relative to those who prioritize in-group rescue. Caution must be exercised when extending these findings beyond the immediate context of intergroup dilemmas.

To address these limitations, future research efforts could explore differences in people’s hypocrisy evaluations of preferential rescuing behaviors and non-rescuing behaviors. It is plausible that individuals’ assessments of hypocrisy may be diminished when confronted with scenarios involving “neither rescuing”, assuming the underlying mechanisms of hypocrisy perceptions hold true. This is because to the bystander, the actor’s intrinsic self-interested motivation is consistent with an outward display of self-interest, which is not hypocritical, albeit unethical.

Moreover, it would be valuable for future studies to extend their investigations beyond intergroup dilemmas and explore the potential general propensity to perceive highly altruistic behaviors as hypocritical. By adopting more rigorous methodologies and broadening the scope of investigation, subsequent studies can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals perceive and evaluate manifestations of high selflessness.

Conclusion

This study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature by uncovering and validating the phenomenon of hypocritical judgments regarding the prioritization of rescue for out-group individuals in intergroup dilemmas. The findings provide valuable insights into the experience of hypocrisy and its implications for moral evaluations. Specifically, individuals demonstrated a tendency to perceive the act of sacrificing the in-group to save the out-group as hypocritical, resulting in negative emotions and diminished moral evaluations. Moreover, this study challenges the traditional understanding of hypocrisy by distinguishing it from the focus on whether hypocrites’ words and actions are inconsistent with each other. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of observer interpretations, highlighting that hypocrisy perceptions may also arise from bystanders’ cognitive conflict between the target’s self-interested motivational projections and the targets ultimately demonstrated altruistic behaviors. This nuanced understanding adds depth to our comprehension of hypocrisy in intergroup contexts.

Data Sharing Statement

The data and material that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the South China Normal University Ethics Committee.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from individual.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was funded by The MOE Project of Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences in Universities (Grant Number: 22JJD190006), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (31970984).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. McManus RM, Kleiman-Weiner M, Young L. What we owe to family: the impact of special obligations on moral judgment. Psychol Sci. 2020;31(3):227–242. doi:10.1177/0956797619900321

2. Law KF, Campbell D, Gaesser B. Biased benevolence: the perceived morality of effective altruism across social distance. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2021;3:014616722110027.

3. Ames DR. Inside the mind reader’s tool kit: projection and stereotyping in mental state inference. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2004;87(3):340–353. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.340

4. Ames DR. Strategies for social inference: a similarity contingency model of projection and stereotyping in attribute prevalence estimates. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2004;87(5):573–585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.573

5. Cadinu MR, Rothbart M. Self-anchoring and differentiation processes in the minimal group setting. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1996;70(4):661–677. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.661

6. Krueger J, Clement RW. Inferring category characteristics from sample characteristics: inductive reasoning and social projection. J Experim Psychol. 1996;125(1):52–68. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.125.1.52

7. Greenwald AG, Ronis DL. Twenty years of cognitive dissonance: case study of the evolution of a theory. Psychol Rev. 1978;85(1):53–57. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.85.1.53

8. Miller DT. The norm of self-interest. Am Psychologist. 1999;54(12):1053–1060. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1053

9. Tsay C-J, Shu LL, Bazerman MH. Naivete and cynicism in negotiations and other competitive contexts. Acad Manag Anna. 2011;5:495–518. doi:10.5465/19416520.2011.587283

10. Walmsley J, O’Madagain C. The worst-motive fallacy: a negativity bias in motive attribution. Psychol Sci. 2020;31(11):1430–1438. doi:10.1177/0956797620954492

11. Batson CD, Kobrynowicz D, Dinnerstein JL, Kampf HC, Wilson AD. In a very different voice: unmasking moral hypocrisy. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1997;72(6):1335–1348. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1335

12. Batson CD, Thompson ER, Seuferling G, Whitney H, Strongman JA. Moral hypocrisy: appearing moral to oneself without being so. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1999;77(3):525–537. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.525

13. Batson CD, Thompson ER, Chen H. Moral hypocrisy: addressing some alternatives. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83(2):330–339. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.330

14. Tedeschi JT, Schlenker BR, Bonoma TV. Cognitive dissonance: private ratiocination or public spectacle? Am Psychologist. 1971;26(8):685–695. doi:10.1037/h0032110

15. Simons T. Behavioral integrity: the perceived alignment between managers’ words and deeds as a research focus. Organ Sci. 2002;13(1):18–35. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.1.18.543

16. Greenbaum RL, Mawritz MB, Piccolo RF. when leaders fail to “walk the talk”: supervisor undermining and perceptions of leader hypocrisy. J Manage. 2015;41(3):929–956. doi:10.1177/0149206312442386

17. Jones EE, Davis KE. From acts to dispositions the attribution process in person perception. Advan Experim Soc Psychol. 1966;2(4):219–266.

18. Bond CF, Omar A, Pitre U, Lashley BR, Skaggs LM, Kirk CT. Fishy-looking liars - deception judgment from expectancy violation. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1992;63(6):969–977. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.969

19. Lucas BJ, Galinksy AD, Murnighan KJ. An intention-based account of perspective-taking: why perspective-taking can both decrease and increase moral condemnation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2016;42(11):1480–1489. doi:10.1177/0146167216664057

20. Newman GE, Cain DM. Tainted altruism: when doing some good is evaluated as worse than doing no good at all. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(3):648–655. doi:10.1177/0956797613504785

21. Kahneman D, Dale T. Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:136–153. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.136

22. Critcher CR, Dunning D. Egocentric pattern projection: how implicit personality theories recapitulate the geography of the self. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):1–16. doi:10.1037/a0015670

23. Minson JA, Monin B. Do-gooder derogation: disparaging morally motivated minorities to defuse anticipated reproach. Soc Psycholog Person Sci. 2012;3(2):200–207. doi:10.1177/1948550611415695

24. Aquino K, Reed A. The self-importance of moral identity. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83(6):1423–1440. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423

25. Blasi A, Zimmerman KK, Mitchell MC. Moral functioning: moral understanding and personality. Moral Devel. 2004;131:435–446. doi:10.1242/dev.00922

26. Monin B. Holier than me? Threatening social comparison in the moral domain. Revue Internat De Psychol Soc Internat Rev Soc Psychol. 2007;20(1):53–68.

27. Alicke MD. Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(4):556–574. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.556

28. Tesser A. Emotion in social comparison and reflection processes. Jsul Twills Soc. 1991;1991:1.

29. Smith A. The theory of moral sentiments. Hist Econ Thought Books. 2005;2005:1.

30. Tasimi A, Dominguez A, Wynn K. Do-gooder derogation in children: the social costs of generosity. Front Psychol. 2015;6:6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00006

31. Davis MH. Social projection to liked and disliked targets: the role of perceived similarity. J Experim Soc Psych. 2017;70:286–293. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.11.012

32. Laurent SM, Clark BAM, Walker S, Wiseman KD. Punishing hypocrisy: the roles of hypocrisy and moral emotions in deciding culpability and punishment of criminal and civil moral transgressors. Cognit Emot. 2014;28(1):59–83. doi:10.1080/02699931.2013.801339

33. Saltzstein HD, Kasachkoff T. Haidt’s moral intuitionist theory: a psychological and philosophical critique. Rev General Psychol. 2004;8:273–282. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.273

34. Skoe EEA, Eisenberg N, Cumberland A. The role of reported emotion in real-life and hypothetical moral dilemmas. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(7):962–973. doi:10.1177/014616720202800709

35. Desteno D, Valdesolo P, Bartlett MY. Jealousy and the threatened self: getting to the heart of the green-eyed monster. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):626–641. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.626

36. Wisneski DC, Lytle BL, Skitka LJ. Gut Reactions. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(9):1059–1063. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02406.x

37. Merritt AC, Monin B. The trouble with thinking: people want to have quick reactions to personal taboos. Emotion Rev. 2011;3(3):318–319. doi:10.1177/1754073911402386

38. Carrigan B, Adlam ALR, Langdon PE. The neural correlates of moral decision-making: a systematic review and meta-analysis of moral evaluations and response decision judgements. Br Cognition. 2016;108:88–97. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2016.07.007

39. Fowler Z, Law KF, Gaesser B. Against empathy bias: the moral value of equitable empathy. Psychol Sci. 2021;32(5):766–779. doi:10.1177/0956797620979965

40. Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(3):242–249. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006

41. Cohen TR, Montoya RM, Insko CA. Group morality and intergroup relations: cross-cultural and experimental evidence. Personal Soc Psychol Bullet. 2006;32(11):1559–1572. doi:10.1177/0146167206291673

42. Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH. Mapping the moral domain. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2011;101(2):366–385. doi:10.1037/a0021847

43. Goodwin GP, Piazza J, Rozin P. Moral character predominates in person perception and evaluation. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2014;106(1):148–168. doi:10.1037/a0034726

44. Effron DA, Markus HR, Jackman LM, Muramoto Y, Muluk H. Hypocrisy and culture: failing to practice what you preach receives harsher interpersonal reactions in independent (vs. interdependent) cultures. J Experim Soc Psych. 2018;76:371–384. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.009

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.