Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 12

The Impact of a Training Program on Clinical Pharmacists on Pharmacy Clinical Services in a Tertiary Hospital in Hunan China

Authors Xu P, Hu YY, Yuan HY, Xiang DX, Zhou YG, Cave AJ , Banh HL

Received 24 August 2019

Accepted for publication 18 November 2019

Published 27 November 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 975—980

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S228537

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Ping Xu,1 Yi Yun Hu,1 Hai Yan Yuan,1 Da Xiong Xiang,1 Yan Gang Zhou,1 Andrew J Cave,2 Hoan Linh Banh2

1Department of Pharmacy, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan 410008, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

Correspondence: Ping Xu

Department of Pharmacy, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, 139 Renmin Middle Road, Changsha, Hunan 410008, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86-138-7488-2504

Email [email protected]

Hoan Linh Banh

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, 6-10 University Terrace, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Tel +1 780-248-1835

Email [email protected]

Background: Prior to 2015, clinical consultation was the only clinical service provided by clinical pharmacists in Changsha Second Hospital. Between 2015 and 2017, a train-the-trainer program was implemented to train clinical pharmacists to provide pharmaceutical care and to conduct clinical research. The objective of the study is to examine the impact on the clinical services provided by pharmacists after the implementation of the train-the-trainer program.

Patients and methods: Between 2004 and 2014, all completed clinical consultation activities were tallied and summarized. The results from the tallied consultation activities were used as a baseline for clinical activities provided by pharmacists prior to the training. A structured training program was implemented between 2015 and 2017 to train clinical pharmacists to provide pharmaceutical care. After the implementation of the training program was completed, all clinical activities provided by pharmacists between January 2017 and December 2017 were documented in the clinical workload form. The clinical activities completed by each pharmacist were tallied and summarized.

Results: Between 2004 and 2014, a total of 6569 (average 657 per year) pharmacy consultations were requested and completed from a total of 44 departments. In 2017, a total of 15,078 hrs of clinical activities were logged. The pharmacists completed 3481 consultations in 2017 (an increase of 430%), averaging 316 consultations for each pharmacist and 271.8 hr per pharmacist. Over 2000 hrs (of the 15,078 hrs) were spent on direct patient care by the pharmacists.

Conclusion: This study shows that there was a 430% increase in clinical pharmacy consultation services provided by the clinical pharmacists after the implementation of the training program. This is directly related to the number of well-trained pharmacists available. After the implementation of the train-the-trainer program, the range of services as well as the number of clinical services and clinical hours spent on providing pharmaceutical care have significantly increased.

Keywords: clinical pharmacy, pharmacy consultation, pharmacy services, pharmaceutical care

Introduction

Clinical pharmacy services are integral parts of patient care. It has been shown that clinical pharmacy services have reduced morbidity and mortality rates, reduced hospitalization and provided economic benefits to health-care system.1–3 In 2009, the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China introduced an aggressive policy to provide affordable and equitable basic health care for everyone in China by 2020. The areas of focus for the reform include expansion of insurance coverage for more than 90% of the people, creation of a national essential medicine system to meet the people’s medical needs, improvement of the primary care health system which would refer patients to specialists or hospitals, and provide equal and available public health-care services.4–6 As a result, dramatic change to the delivery of health-care efficiency is required to meet the objectives of the issued health-care reform. To assist this, the Ministry of Health in China mandated clinical pharmacy services be integrated into hospitals.7 The new role is aimed to provide direct patient care by pharmacists and to foster effective and efficient use of medications.

To prepare the pharmacists to assume this new role, universities such as Peking University have offered 6-year dual Bachelor and Master Degrees in clinical pharmacy since 2011.8 In addition, many pharmacists in China are training overseas and as well, foreign academics are visiting China to assist the pharmacists in implementing clinical services in China.9,10

The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, consists of almost 4000 inpatient beds with over 110,000 admissions annually. There are 44 medical service departments in the hospital. In early 2000, the department of pharmacy initiated the clinical pharmacy program, by providing consultation services to all physicians in the hospital. The service was fully implemented in 2004 when the department appointed a Clinical Pharmacy Leader. The physicians would submit a consultation request by completing a request form and notifying the clinical pharmacy department by telephone after patient care rounds. Each clinical pharmacist is assigned to cover consultations from specific areas such as oncology, pediatric intensive care unit, cardiovascular intensive care unit, cardiology, endocrinology, transplant, pulmonary and infectious diseases. The consultations must be completed on the same day of request.

In 2015, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University collaborated with the University of Alberta, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry/Department of Family Medicine to implement a train-the-trainer program in the department of pharmacy.9,11,12 A clinical pharmacist with a Doctor of Pharmacy degree, from the Department of Family Medicine, developed and implemented the program. The main objectives of the train-the-trainer program were to teach clinical pharmacists to 1) provide direct patient care, 2) conduct clinical research and 3) mentor other clinical pharmacists throughout China.

Aim of the Study

The objectives of the study are 1) to examine clinical services provided by the department of pharmacy prior to 2015 and 2) to evaluate the expansion of clinical pharmacy services post 2015.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University Ethics Committee.

Method

Design

The train-the-trainer program consisted of a mix of one-on-one and group teaching methods. As a group, the pharmacists were given weekly therapeutic lectures. Each morning, the clinical pharmacists attended daily patient care rounds and addressed any patient issues with the physicians. In the afternoon, the trainer and the pharmacist had a one-on-one discussion about the patients for whom he/she provided care.

In 2015, prior to the implementation of the train-the-trainer program, the clinical pharmacy leader and the trainer assessed all clinical services provided by the department of pharmacy. Following the implementation of the train-the-trainer program, a workload documentation form was developed to assist clinical pharmacists to document their daily clinical activities. The clinical activities consisted of six categories: consultation, clinical (patient care rounds), training and education, research, academic, and others. All clinical pharmacists were required to log the time spent on 15 mins increment on each category daily and submit the documentation to the clinical pharmacy leader each month.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the total activities and the frequency of each of the categories.

Results

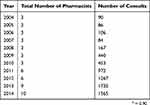

Prior to 2015, consultation was the predominant clinical service that was provided by the clinical pharmacists. Between 2004 and 2014, there was a total of 6569 pharmacy consultations requested and completed from a total of 44 departments (Table 1). Majority (n=1596, 28.4%) of the consultations came from the neurosurgical ward, which was the first department to be serviced by a pharmacist. The most frequent consultation requests (57.8%) were from surgical departments (Neurosurgical, Orthopedic, Thoracic surgery, Spinal Surgery, Urological Surgery). The consultation requests generally increased over 11 years (Table 2). The most common reason for consultation requests was regarding antimicrobial therapy (Table 3). Of note, there is a positive correlation with the number of clinical pharmacists available and consultation requests (r = 0.95), p < 0.01. After the completion of the training, the clinical pharmacists began the documentation of clinical activities starting January 2017. In 2017, there were 13 clinical pharmacists, which is an increase of three clinical pharmacists since 2014. The total number of pharmacist hours logged was 15,078 with most time spent on research which was closely followed by consultation. The pharmacists completed 3481 consultations in that year averaging 316 consultations each and 271.8 hrs per pharmacist. Over 2000 hrs were spent on patient care rounds by 12 out of 13 pharmacists (Table 4).

|

Table 1 Overall Total Consults by Services |

|

Table 2 Total Number of Pharmacists and Consults Completed |

|

Table 3 Consultation Services Provided Between 2004 and 2014 |

|

Table 4 Clinical Services Provided by Clinical Pharmacists in 2017 |

Discussion

Since the early 1990s, the economic benefits of clinical hospital pharmacists in North America are well documented.13–15 In addition, it has been shown that clinical pharmacists reduced medication errors, improved medication utilization, enhanced medication adherence and engaged in antibiotic stewardship.16–19 New policies in China have recently led to the implementation of clinical pharmacy services in hospitals across the country. There is a mandate by the government to have at least five clinical pharmacists in each tertiary hospital. The new government policies provide clinical pharmacists an opportunity to demonstrate to both the hospital administration and physicians that their training and skills offer enhanced patient care.

The results from this study clearly show that the clinical pharmacist service was greatly in demand and utilized at the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Between 2004 and 2010, the pharmacy department only had three clinical pharmacists. During the period of 2006 and 2007, two of the pharmacists were pursuing their PhD degree while working in the hospital. As a result, the number of consultations declined (Table 1). The number of consultations, however, more than doubled when the two pharmacists completed their degree (2008 = 167, 2009 = 440). In 2011, the number of pharmacists doubled and so did the consultations (2010 = 453, 2011 = 972). It appears that pharmacist availability has a direct effect on consultation rate, which has a major effect on clinical management. Because the computerized patient electronic database was not fully completed until January 2014, we selected 2014 to analyze the type of services requested by consultation. Antimicrobial use consultation was the service most requested in 2014.

After the implementation of the train-the-trainer program, the clinical pharmacists were able to expand clinical pharmacy services beyond consultations. A new activity introduced was to participate in patient care rounds. The clinical pharmacists were able to integrate into medical teams and participate in providing direct patient care with the physicians. The clinical pharmacists proactively identified therapy-related problems, adjusted dose based on patient age or comorbidity such as renal insufficiency, monitored both efficacy and toxicity and followed up on daily patient care rounds. One of the pharmacists (#10) spent significant amount of time in research and did not complete any consultation or patient care rounds. The main reason is this pharmacist was prepared to submit a grant application to go abroad to extend his research. He did extra research hours and another pharmacist (#9) took over his consultations. This also demonstrates the flexibility according to skill sets within the department. In addition, one pharmacist (#7) only submitted 724 hrs of clinical activities because she was on maternity leave for 6 months in 2017. The last two pharmacists (#12, #13) are new clinical pharmacists who joined the clinical pharmacy department mid-2017. As a result, their total clinical activities are much lower than the rest of the pharmacists. Clinical pharmacist #1 contributed significant amount of time in academia. The main reason is because that pharmacist has a faculty cross-appointment with the Central South University to teach pharmacy students clinical pharmacy.

In addition to consultations and patient care rounds, the clinical pharmacists were able to identify issues related to patient care in the hospital and conduct clinical research to improve the delivery of care. For example, the hospital uses acetaminophen and diclofenac combination product administered intramuscularly instead of opioid for post-operatively pain. A pharmacist noticed that there was an increased number of surgical patients with an elevated serum creatinine after surgery. The pharmacists conducted a chart review which showed that there was an association between diclofenac use and acute renal injury.20

To our knowledge, this is the first extensive descriptive reporting of clinical pharmacy services in a tertiary teaching hospital in China. The study highlights the clinical pharmacy activities provided in a tertiary teaching hospital after successfully implementing a train-the-trainer program. Because this was such a novel activity, there were some growing pains evident. For example, although clinical pharmacists logged their clinical activities daily, some data were still missing on the daily basis which needs to be corrected.

Conclusion

There has been an increase in clinical pharmacy services after the implementation of the train-the-trainer program. This is directly correlated to the number of well-trained pharmacists. After the implementation of the train-the-trainer program, the range of services as well as the number of clinical services and clinical hours spent on providing pharmaceutical care were significantly increased.

Ethics Approval

The study received ethics approval from the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the clinical pharmacists for their participation and Yi Wen Xiao, Yi Ping Liu, Qiong Lu, and Qiang Yong Yan for assisting with the clinical pharmacists.

Author Contributions

- Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; HLB, PX, AJC, DXX, YGZ, YYH, HYY

- Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; HLB, PX, AJC, DXX, YGZ, YYH, HYY

- Final approval of the version to be published; HLB, PX, AJC, DXX, YGZ, YYH, HYY

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. HLB, PX, AJC, DXX, YGZ, YYH, HYY.

Disclosure

All authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1. Schumock GT, Butler MG, Meek PD, Vermeulen LC, Arondekar BV, Bauman JL. 2002 task force on economic evaluation of clinical pharmacy services of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Evidence of the economic benefit of clinical pharmacy services: 1996–2000. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:113–132. doi:10.1592/phco.23.1.113.31910

2. Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:481–493. doi:10.1592/phco.27.4.481

3. MacLaren R, Bond CA, Martin SJ, Fike D. Clinical and economic outcomes of involving pharmacists in the direct care of critically ill patients with infections. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3184–3189. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f2269

4. Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet. 2009;373:1322–1324. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60753-4

5. Central Committee of the Communist Party and State Council. People’s Republic of China. The standing conference of State Council of China adopted guidelines for furthering the reform of health-care system in principle. Available from: http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/ 192009-04/06/content_11138803.htm.

6. Liu Q, Wang B, Kong Y, Cheng KK. China’s primary health-care reform. Lancet. 2011;377:2064-6.

7. WHO: Quality and accreditation in health care services A global review. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68410/WHO_EIP_OSD_2003.1.pdf;jsessionid=B012C17ABF0DB61618E8ACEBF1C3C721?sequence=1.

8. Ryan M, Shao H, Yang L, et al. Clinical pharmacy education in China. AJPE. 2008;72:129.

9. Banh HL, Xu P, Xiang DX, Cave A. Innovative training program for pharmacists in the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Int J Pharm. 2014;4(3):1–4.

10. Liu GJ. Hospital pharmacy practice in the People’s Republic of China. AJHP. 1982;39:1487–1490.

11. Banh HL, Cave AJ. Implementation of the train-the-trainer program for pharmacists in China. FMCH. 2016;4:60–63. doi:10.15212/FMCH.2016.0104

12. Xu P, Xiang DX, Cave AJ, Banh HL. Impacts from the implementation of a novel clinical pharmacist training program in Changsha, Hunan province, China. FMCH. 2017;5:1–4.

13. Anderson SV, Schumock GT. Evaluation and justification of clinical pharmacy services. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(6):539–545. doi:10.1586/erp.09.57

14. Schumock GT, Meek PD, Ploetz PA, Vermeulen LC. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services–1988–1995. The publications committee of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(6):1188–1208.

15. MacLaren R, Bond CA. Effects of pharmacist participation in intensive care units on clinical and economic outcomes of critically ill patients with thromboembolic or infarction-related events. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(7):761–768. doi:10.1592/phco.29.7.761

16. Bond CA, Raehl CL. 2006 national clinical pharmacy services survey: clinical pharmacy services, collaborative drug management, medication errors, and pharmacy technology. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):1–13. doi:10.1592/phco.28.1.1

17. Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and adverse drug reactions in United States hospitals. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(6):735–747. doi:10.1592/phco.26.6.735

18. Zhou Y, Ma LY, Zhao X, Tian SH, Sun LY, Cui YM. Impact of pharmacist intervention on antibiotic use and prophylactic antibiotic use in urology clean operations. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(4):404–408. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12275

19. Bessesen MT, Ma A, Clegg D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: comparison of a program with infectious diseases pharmacist support to a program with a geographic pharmacist staffing model. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(6):477–483. doi:10.1310/hpj5006-477

20. Zhu Y, Xu P, Wang Q, et al. Diclofenac—acetaminophen combination induced acute kidney injury in postoperative pain relief. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:19–26. doi:10.18433/J3SH21

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.