Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

The Healthy Context Paradox Between Bullying and Emotional Adaptation: A Moderated Mediating Effect

Authors Pu J, Gan X, Pu Z, Jin X, Zhu X, Wei C

Received 3 November 2023

Accepted for publication 9 April 2024

Published 16 April 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 1661—1675

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S444400

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Junwei Pu,1 Xiong Gan,1 Zaiming Pu,2 Xin Jin,1 Xiaowei Zhu,1 Chunxia Wei3

1College of Education and Sports Sciences, Yangtze University, Jingzhou City, Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Marxism, ENSHI POLYTECHNIC, Enshi City, Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China; 3Foreign languages college, Jingzhou University, Jingzhou City, Hubei Province, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiong Gan, Department of Psychology, College of Education and Sports Sciences, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, 434023, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 7168062663, Email [email protected] Chunxia Wei, Foreign languages college, Jingzhou University, Jingzhou, 434023, Hubei, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Bullying is a significant concern for young people, with studies consistently showing a link between bullying and negative emotional consequences. However, the mechanisms that underlie this association remain unclear, particularly in terms of the classroom environment. This study aimed to explore the paradoxical phenomenon between bullying victimization and emotional adaptation among junior high school students in China, using the hypothesis of the healthy context paradox.

Methods: The study involved 880 students (565 girls; Mage=14.69; SD=1.407 years), and data were collected using self-reported surveys. The findings of the study, utilizing multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) techniques, demonstrated a cross-level moderated effect of classroom-level bullying victimization on the relationship between individual bullying victimization and emotional adaptation.

Results: Specifically, the results indicated that in classrooms with higher levels of victimization, the association between individual bullying victimization and increased depressive symptoms and State&Trait anxiety was more pronounced. These findings support the “Healthy context paradox” hypothesis in the Chinese context and provide insight into the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

Discussion: The results suggest that the classroom environment plays a crucial role in shaping the emotional consequences of bullying and that addressing classroom victimization is crucial for promoting emotional health among young people. By understanding the mechanisms that underlie the association between bullying and emotional consequences, interventions can be developed to target the underlying factors that contribute to this paradoxical phenomenon. Overall, the study provides new insights into the complex relationship between bullying and emotional health among young people, highlighting the importance of considering the classroom environment in addressing this issue.

Keywords: the healthy context paradox, bullying victimization, emotional adaptation, the level of classroom victimization

Introduction

Bullying victimization, commonly defined as “being physically or mentally hurt by other people for a special time”, is a significant issue,1 particularly within the school education system. Research in this field has gained substantial popularity globally, including within the Chinese education system. In recent years, there has been a growing interest and a significant body of research dedicated to studying bullying prevalence2,3 and its impact on students4–6 within the school system in China. Some studies have demonstrated that being bullied in school may lead to depressive and anxiety symptoms,7 as well as other negative behaviors such as aggression, self-harm, and criminal behavior.8,9 As a result, researchers have investigated the causes and factors that contribute to bullying victimization in order to prevent it. One such theory contends that the environmental circumstances play a critical role in bullying victimization,10 and bullying behaviors are more likely to occur in challenging environments.11 However, with the development of research in this field, some researchers have suggested that bullying victimization can still occur even in healthy environments, and victims of bullying may experience more severe problems in adaptation, leading to a phenomenon known as the “Healthy context paradox”.12,13

“The Healthy Context Paradox”

This concept has garnered significant attention from scholars in China and abroad. It is generally committed that a healthy context is positive, safe and chilling, and an individual feels comfortable in such environment.14 In addition, some research has indicated that the rate of individual victimization in a healthy classroom was lower than a bad classroom, and it becomes one indicator of the healthy contexts.12,15 However, recent studies have found that a healthy classroom may be more harmful to those who get victimization. These effects can manifest in various ways, including internalizing problems such as depression,16,17 as well as academic difficulties and learning challenges.18 Compared to the unhealthy context, students who get hurt in a healthy context may report more problems with adaptation. Furthermore, some studies have indicated that even if significant efforts are made to improve the original negative environment, the problems in adaptation may worsen.19 The paradox has attracted scholars’ eyes for years, and it has been confirmed in many countries and areas. But there’s not much empirical evidence on this field in Chinese context. Thus, it is necessary to examine the “healthy context paradox” in Chinese context.

The Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Emotional Adaptation

According to the Mental Health Development Report of Chinese Citizens for 2019–2020, adolescents in China are facing many problems, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, and pressure.20 Therefore, the current study focuses on these problems, which are all aspects of emotional adaptation. However, most studies have not normalized the classification of problems in emotional adaptation. Studies have examined the relationship between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms, while others have examined the relationship between bullying victimization and anxiety symptoms,12,13,16,21 but none have proposed the concept of emotional adaptation. Therefore, this study incorporate the comprehensive concept into our research framework. Emotional adaptation is an indicator of measuring the mental health condition in adolescence and represents one’s internal moods. Scholars have reached a consensus that depressive symptoms, anxiety, happiness, and other emotions are indicators of emotional adaptation.22 When an individual experiences bullying, it can lead to negative cognition and, in turn, bad moods or even emotional problems. Empirical evidence confirms that students who experience bullying in school may develop depressive and anxiety symptoms.7,23,24 Scholars have looked for interventions that can impact bullying and emotion, and many of them have strong opinions about the environment, believing that promoting a healthy environment can make an individual feel better and avoid bullying victimization.10 So far, it has been generally accepted that a healthy environment is positively helpful to humans, and it has become an unconscious cultural cognition. Therefore, the current study hypothesizes that the relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation will also be confirmed.

The Mediating Role of School Belonging in Healthy Context Paradox

School belonging refers to the psychological sense of comfort and security,25,26 which is gradually formed by students in the school environment by gaining the school’s dependence, teachers and students’ acceptance, support, and respect.5,27 Additionally, students have a clear identity and feel that they are an important member of the school and class.28 A student’s sense of school belonging is a necessary condition for establishing a foothold and pursuing excellence on campus, and this sense of belonging cannot be separated from the school and class environment.25–27,29,30 Thus, the current study also needs to link school belonging to the “healthy context paradox” and investigate the role of school belonging in this paradox.Based on previous studies, we conclude that school belonging plays a mediating role between bullying and emotional adjustment, as being bullied leads to a lower level of school belonging.2,31 It has been suggested that individuals perceive others’ aggression as a form of exclusion, hostility, and disrespect,30,32 resulting in a lack of school belonging. It has also been found that bullying can lead to the impairment of peer relationships,33 which, in turn, leads to a reduction in school belonging.34 On the other hand, the decrease in school belonging may lead to a series of problems in emotional adaptation. Some studies have shown that social support can significantly predict emotional adaptation, with more social support leading to fewer emotional adaptation problems.6,25,30 Conversely, the less social support there is, the more emotional problems there are.35,36 School belonging can also significantly predict an individual’s emotional state. According to the 2019 OECD study on the social and emotional capacities of the world’s adolescents, school belonging has been found to have a significant positive effect on an individual’s ability to regulate emotions.20 In conclusion, school belonging plays a mediating role between bullying and emotional adaptation.

The Moderated Role of the Level of Classroom Victimization in Healthy Context Paradox

According to the existed research, children who experienced bullying may reflect depressive or anxiety symptoms.3 On the flip side, a study revealed that not everyone shows the symptoms mentioned above in that way.37 That implies that something must play a moderating role and cause individuals to exhibit varying circumstances. Furthermore, it is well acknowledged that the environment has a significant impact on these issues, and it can be well reflected by the level of victimization of a classroom.38,39 So we have considerable reasons to believe that the level of classroom victimization moderates the relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation.

It is generally acknowledged that a classroom with low-level victimization does promote young teenagers’ wellbeing.40 However, even most of us know the great importance of interfering with bullying victimization, and the level of victimization had been already decreased, researchers have ignored the situation that the limited victimization still exist. On the flip side, students who still get hurt may report more and worse problems.12,41,42

The term “the level of classroom victimization” refers to the environmental extent of bullying, the incidence rate of it, and how students get victimization in a classroom. Students in a class get verbal, physical, psychological attack, these experiences can be well reflected by the level of classroom victimization.43 According to a study, the anti-victimization project’s efforts to raise the degree of anti-victimization attitudes of students had positively impacted the classroom atmosphere.23,44,45 Moreover, it has been found that a student’s positive emotional state is strongly correlated with the level of classroom victimization. However, when it comes to bullying-related issues, even those in a positive class may experience negative consequences.41

The Present Study

To our knowledge, existed studies have focused one’s academic performance and depression when it comes to the healthy context paradox,17,18,21 but little research has investigated the role of emotional adaptation when discussing the paradoxical relationship between individual bullying victimization and mental health outcomes. Based on the lack of validation of previous research findings in the Chinese context regarding the topic, this study aims to examine the relationship between individual bullying victimization and emotional adaptation. It employs a multi-level structural equation modeling approach to explore the associations between variables at both the individual and classroom levels, which is considered more advanced and scientifically rigorous than previous studies. Furthermore, this study introduces the concept of emotional adaptation, which has been rarely investigated in this field of research. Additionally, it utilizes a different mediator variable compared to previous studies to discuss the mechanisms underlying the healthy context paradox. Overall, it proposes a moderated mediating model to investigate this relationship, incorporating four hypotheses in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Hypothesized Model of the Relationship between IV and Emotional Adaptation, with SB as the Mediator and CV as the Moderator. |

H1: Individual victimization can positively predict emotional adaptation problems like depressed or anxiety symptoms.

H2: School belonging will mediate the relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation.

H3: The level of classroom victimization will moderate the relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation.

H4: The link between individual victimization and emotional adaptation will become stronger under the low level of classroom victimization.

By empirically validating these hypotheses, whether the “healthy context paradox” applies to the relationship between individual bullying victimization and emotional adaptation can be also examined. This research will provide insights into whether the paradox holds true within the Chinese context. Through the examination of this phenomena, this study will make contributions to the advancement of knowledge and provide valuable insights for addressing the complex issue of bullying and its impact on emotional well-being within the Chinese context.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sampling method employed in this study was cluster sampling. To account for the relationship between individual and classroom levels, the entire classroom was selected as the primary sampling unit, with individuals nested within each class. The selection of classrooms was randomized to ensure unbiased representation. Due to the specific focus of our research topic, it was imperative to consider a comprehensive range of participants, not solely limited to students who have experienced bullying victimization. This necessitated the inclusion of other groups for comparison with the victimized group. Therefore, a comprehensive participant selection strategy was adopted. The final sample consisted of 880 students (565 girls) with a mean age of 14.69 ± 1.407 years, drawn from 20 classrooms in various middle schools located in Hubei, China. The classroom sizes ranged from 35 to 50 students, with an average of 44 students per classroom. Participants were recruited from all grades (7th: 262; 8th: 191; 9th: 427, equivalent to 6th, 7th, and 8th grade in the US public school system), and 190 of these students were only-children. In terms of participants’ parents, 24.8% of fathers and 33.5% of mothers possessed a primary education or lower, while only 5.8% of fathers and 4.1% of mothers had received higher education or post-graduate education. The recruitment period for this study started on February 22th, 2022 and ended on May 15th, 2022. Participants provided informed consent before participating in this study. We obtained both written and verbal consent from the participants. For minor participants, we first obtained verbal consent from their parents or guardians through phone calls or face-to-face communication. The verbal consent was documented by our research staff. This granted permission for their child to participate. We also kept a record of any students whose parents did not provide consent, and excluded them from the study. When administering surveys to the minors, we also obtained verbal assent from the children to confirm they were willing to participate. The verbal assent was witnessed by research staff members on site. In this way, we ensured proper informed consent procedures were followed, with consideration for both parental permission and child assent. To ensure the accuracy of the language, all the words on the questionnaire were translated into Chinese, and all the words on the paper were definitely understandable. Prior to testing, the survey was introduced to teachers and students, and the test was conducted with the headmaster’s permission. During the test, students were asked to answer all the questions on the questionnaire paper honestly. Students completed the confidential questionnaire paper during their regular school time, taking a total of 30–45 minutes. The testing process was approached in a relaxing and natural context to ensure that there was no effect on the subjects. Following testing, all survey forms were gathered, and as a reward, students could choose between receiving snacks or cash. The test period lasted for about 3 months, and data from 880 samples were obtained.

Measures

Individual-Level Bullying Victimization

Participants reported their experiences of bullying victimization using a six-item questionnaire adapted from the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire.1 To ensure linguistic accuracy, the present study opted for the revised Chinese version of the questionnaire.46 The questionnaire used a scoring system ranging from 1 to 5 points (1 = never; 2 = once or twice; 3 = several times a month; 4 = once a week; 5 = several times a week), with higher scores indicating greater self-reported bullying victimization. The questionnaire demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.905, and strong validity with a high KMO coefficient of 0.893. Each student’s score was aggregated and averaged to reflect the level of individual-level bullying victimization.

School Belonging

The Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale28 was used to assess how students feel about being accepted or respected in their classroom, using a total of 18 items. The scale includes two portions: 13 belonging items and 5 resistance items, with all items rated on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all; 2 = disagree; 3 = basically disagree; 4 = basically agree; 5 = agree; 6 = of course). Belonging items were normally aggregated, while resistance item scores were reversed. Both portions demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.922 for belonging items and 0.773 for resistance items, and an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.899. Additionally, the questionnaire demonstrated good validity, as evidenced by a high KMO coefficient of 0.941.

Emotional Adaptation

Previous studies have used various indicators of emotional adaptation, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, happiness, and loneliness, to reflect an individual’s emotional condition. In the current study, depressive and anxiety symptoms were chosen as the indicators, and two separate survey instruments were used to assess their quality.

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale47 was used to assess whether students experienced symptoms of depression, using a total of 20 items. All items were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = never or seldom; 2 = sometimes; 3 = usually or half-time; 4 = most of the time), enabling students to receive a total score ranging from 20 to 80 points. A previous study suggested that participants may experience depressive symptoms when they score above 20 points (out of a total score of 0–60). In the present study, students were considered to have depressive symptoms if they scored above 40 points. The scale demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.928, and strong validity with a high KMO coefficient of 0.952.

The State-Trait Anxiety

We used The State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI) to assess individuals’ levels of anxiety, including both State Anxiety Scale and Trait Anxiety Scale.48 The scale consisted of a total of 40 items (20 items in each portion) and used a 4-point response scale (1 = not at all; 2 = a little; 3 = some extent; 4 = very much), with higher scores indicating a higher level of anxiety. Both portions demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.923 for state anxiety and 0.829 for trait anxiety. Additionally, the questionnaire demonstrated good validity, as evidenced by a high KMO coefficient of 0.946.

The Level of Classroom Victimization

To assess the quality of the class-level environment, we aggregated and averaged the scores of individual victimization in a classroom to reflect the level of classroom victimization.38,42,43

Control Variables

At the individual level, we selected gender, age, and parents’ education experience as control variables. At the class level, we used grade, class number, and the number of students in a classroom as control variables.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 23.0 and Mplus Version 8.3. Our initial database check revealed no missing values. Harman’s single-factor test was used to examine common method bias, and the results indicated no significant bias (the first factor’s rate was 23.51% < 40%).

As the data collected in our study had two levels (individual-level and class-level), direct analysis was complicated, and the interaction effects between these two levels needed to be confirmed. Due to limited resources and time, our study focused on classroom-level analysis rather than school-level analysis, so we used a two-level structural equation model (MSEM) created using Mplus, and followed the subsequent analytical steps:

Result

Preliminary Analyses

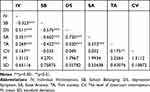

The means (M), standard deviations (SD), and correlation coefficients of main variables are presented in Table 1. In this study, individual victimization (IV) exhibited a mean of 1.3112 (SD=0.65116), indicating that, on average, individuals experienced a moderate to low level of victimization. However, it is noteworthy that approximately 16.2% of the participants reported a level exceeding 1.5, this suggests a considerable prevalence of bullying within the school context. Furthermore, regarding depressive symptoms (DS) with a mean of 1.7967 (SD=0.55782), approximately 32% of individuals reported levels exceeding 2.0. Additionally, for trait anxiety (TA) with a mean of 2.2564 (SD=0.43076), about 25% of individuals exhibited levels surpassing 2.5. These results underscore the significant challenges associated with the emotional adaptation within the school environment in the Chinese context. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the potential link between bullying victimization and emotional adaptation. As expected, individual victimization was positively related to depressive and anxiety symptoms, that means higher level of victimization equals to more emotional problems. Furthermore, individual victimization was negatively related to school belonging, and there’s no correlation between emotional adaptation problems and the level of classroom victimization.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables |

Two-Level Structural Equation Model Analyses

The Null Model

A null model is used to assess the proportion of variance between the individual level and class level, known as the intraclass correlation (ICC). In our study, the ICC values for individual victimization, school belonging, depressive symptoms, state anxiety, and trait anxiety were 0.026, 0.010, 0.012, 0.003, and 0.102, respectively. These results indicated that a multiple structural equation model was needed.

Individual-level Model(M1)

To examine the role of individual victimization, we added “gender” and “individual victimization” into the null model, and the relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation was investigated. To decrease the variance between the individual and class levels, we centered individual victimization by group mean, and “gender” was coded as a dummy variable (gender: boy=1; girl=2). The estimation results indicated that individual victimization had a positive effect on depressive symptoms, state anxiety, and trait anxiety (Bd=0.417, Bs=0.351, Bt=0.161, p<0.001). As there was no significant variability in the slopes for individual-level variables on depressive and anxiety symptoms, the results in the random model were removed.

The Mediating Model(M2)

To test the mediating hypothesis of the effect of school belonging, we added this variable into the individual-level model (M1). The results indicated that school belonging had a significant mediating effect between individual victimization and emotional adaptation. The mediating effect sizes of school belonging between victimization and depression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety were 0.128, 0.147, and 0.083, respectively. Meanwhile, the direct effects of victimization on each indicator of emotional adaptation were 0.357, 0.147, and 0.080, respectively. The mediating effect rates were approximately 28.89%, 50%, and 50.92%, which means that 28.89% of the effect of victimization on depressive symptoms came from school belonging; 50% of the effect of victimization on state anxiety came from school belonging; and 50.92% of the effect of victimization on trait anxiety came from school belonging.

The Class-level Model(M3)

To confirm the “healthy context paradox”, we tested the moderated role of the class-level variable using the model. The results of model 3 showed that the level of classroom victimization had a negative effect on emotional adaptation (Bd=−.827, Bs=−.380, Bt=−1.657), but the relationship between the level of classroom victimization and state anxiety was not significant (ps>0.05). Since the class-level variable belongs to Level 2, we confirmed the cross-level interaction effect. Eventually, we found that the level of classroom victimization played a moderated role between individual victimization and trait anxiety. To further investigate this interaction, we conducted a test of simple slopes for individuals in classrooms that were either high (+1 SD) or low (−1 SD) on the level of classroom victimization. Consistent with the hypothesized “healthy context paradox”, the association between individual victimization and state anxiety was significantly stronger for individuals in classrooms with higher levels of classroom victimization than for students in classrooms with lower levels.

The Moderated Mediating Model(M4)

We combined model 2 and built a moderated mediating model (M4) to test how school belonging works in the moderated model underlying the “healthy context paradox”. To confirm the cross-level moderated effect, we ran a cross-level regression with the regression coefficient from level 1 and the mediating variable from level 2. We then ran another regression with “s” and the moderated variable “w”49. The results of model 4 in Tables 2–4 showed that when the Y variable was “trait anxiety”, the cross-level moderated effect of the level of classroom victimization between school belonging and trait anxiety was significant (B=−1.499, p=0.022<0.05), and the moderated effect between individual victimization and trait anxiety was also significant (B=0.888, p<0.05). When the Y variable was “depressed symptoms”, the moderated effect of the class-level victimization between individual victimization and depressed symptoms was significant (B=−.458, p<0.05). When the Y variable was “state anxiety”, there were no significant cross-level mediating effects.

|

Table 2 Two-Level Model(Y Variable is DS) |

|

Table 3 Two-Level Model(Y Variable is SA) |

|

Table 4 Two-Level Model(Y Variable is TA) |

According to the results presented in Table 4, we noticed that students in a class with a better climate reported a higher level of trait anxiety when they experienced increased victimization. In contrast, the link between individual victimization and trait anxiety becomes weaker when the classroom environment is not good.

As illustrated in Figure 2, a positive relationship was observed between the level of individual victimization and depressed symptoms. This trend line intersected with another trend line and rapidly surpassed its level, indicating that individuals who experience bullying in classrooms with low levels of victimization may suffer more severe negative consequences. Specifically, victims of bullying in such classrooms exhibit higher levels of depression than those in classrooms with high levels of victimization.

|

Figure 2 Moderating Model of CV on the Relationship between IV and DS, with Higher IV Exhibiting Higher Levels of DS in Environments with Lower CV. |

The graphical representation in Figure 3 reveals a positive correlation between the level of individual victimization and trait anxiety, as evidenced by the trend line’s intersection with another at high levels of individual victimization. This observation suggests that individuals who experience victimization in classrooms with low levels of victimization may suffer more severe negative consequences. In particular, such victims exhibit higher levels of trait anxiety in comparison to those in classrooms with high levels of victimization.

Turning to the link between school belonging and trait anxiety, the phenomenon of the “healthy context paradox” also existed. Upon adding two trend lines to the graph, as depicted in Figure 4, it was observed that the trend line representing low levels of classroom victimization intersected with another trend line and rapidly surpassed its level. This finding suggests that in classrooms with low levels of victimization, the negative impact of decreased sense of belonging resulting from bullying may be more pronounced. As seen in Figure 4, this link becomes stronger when students live in a class with a lower level of classroom victimization (+1SD), and it becomes weaker when they live in a class with a higher climate (−1SD). That means decreased school belonging in a good climate classroom represents higher trait anxiety, and decreased school belonging in a bad climate classroom is not as bad.

|

Figure 4 Moderating Model of CV on the Relationship between SB and TA, with Stronger Association between SB and TA in Environments with Lower CV, and Enhanced Negative Impact of SB on TA. |

Discussion

The present study aimed to confirm the hypothesis of the “healthy context paradox” between individual victimization and emotional adaptation, examine the mediating role of school belonging, and the moderated role of the level of classroom victimization, and discuss the mechanism behind them. The results showed that individual victimization could have both a direct impact on emotional adaptation and an indirect impact through the mediating role of school belonging. Furthermore, when exposed to a healthier classroom environment, more negative consequences emerged, and the connection between personal victimization and emotional adaptation became stronger. All of these findings supported the “healthy context paradox” phenomenon and significantly advanced future studies in this field.

Consistent with existing studies, the current study used the same indicator of the environmental level - The level of classroom victimization - as the standard of the environment. In order to reflect the level of environment, the study averaged the sum of all individual-level victimization scores in a class, based on previous research that had also used this method. This approach provides a way to capture the overall level of victimization in a classroom and examine how it interacts with individual experiences of victimization and emotional adaptation.

Building upon this foundation, The current research makes a unique contribution through the construction of three multi-level structural equation models examining emotional adaptation.This analytical approach facilitates the investigation of discrepancies between the individual and classroom environment levels, advancing beyond previous studies. Specifically, by incorporating school belonging as a mediating effect, the present study provides insights into the underlying mechanisms of the “healthy context paradox” and sheds light on how seemingly supportive environments can still have detrimental effects on the outcomes of bullying victims.

The “Paradox” of the Moderated Effect of Class-Level Victimization

The results indicate that the relationship between individual victimization and depressive symptoms, as well as the relationship between individual victimization and trait anxiety, were influenced by different levels of classroom victimization. The lower level of classroom victimization was considered a “healthy context”, while the higher level of it was considered a “bad context”. Consistent with previous research, stronger links were found between individual victimization and emotional adaptation when students were in a “healthy context”. Interestingly, the current study revealed that students in a higher level of classroom victimization reported fewer emotional adaptation problems following incidents of bullying and were more likely to exhibit lower levels of trait anxiety. This suggests that a higher level of classroom victimization may have paradoxically served as a protective factor for these students. And those in a class with a lower level of classroom victimization did worse when faced with incidents of bullying, conversely. These findings highlight the importance of considering the classroom context when examining the impact of bullying on emotional adaptation outcomes.

The “Healthy Context Paradox” Between Individual Victimization and Emotional Adaptation

Another significant finding of this study is the confirmation of the “healthy context paradox”, and the identification of the mediating effect of school belonging that underlies this paradox is a notable achievement. The results of the models indicated that students who experienced victimization in a healthy classroom may report more problems with emotional adaptation50. This conclusion is consistent with previous research that has also confirmed the existence of the “healthy context paradox”.4,42 Moreover, the current study developed a novel structural equation model that incorporates the mediating effect of school belonging and the moderating effect of the level of classroom victimization. The investigation of the mechanism behind this paradox is crucial in understanding how it operates.

Based on social identity theory, individuals are able to easily distinguish differences and perceive homogeneity or heterogeneity within groups.13,51,52 In a healthy classroom environment, individuals who experience victimization may be perceived as “heterogeneous” within the group, as most students in this context are doing well and have not reported any problems.53,54 Moreover, since healthy classrooms are generally associated with favorable outcomes for students, instances of bullying may be less likely to occur. As a result, individuals who experience victimization may feel misunderstood and rejected by their peers,55–57 leading to a loss of sense of safety and belonging and subsequent emotional problems.58,59 Furthermore, since bullying is less common in healthy classrooms, victims may find it difficult to locate peers with similar experiences and may have to cope with the aftermath of victimization alone.45,60 It is important to note that victimization at a young age can have serious emotional consequences, as victims may not yet possess the emotional maturity to handle such situations.53

According to the person-environment fit theory, when individuals feel like they do not fit in their environment, here comes pressure subsequently.61 In the case of students who experience victimization in a healthy classroom environment, the significant “misfit” between their experiences and the positive classroom context can lead to feelings of pressure and a lack of safety or belonging.53,60 Given the unique and specific growing period of adolescence, students may struggle to cope with victimization on their own and may seek comfort from peers who have had similar experiences.58 However, victims of bullying may find it challenging to receive support from peers, as few students may have experienced such victimization.58 Instead, victims may face rejection and misunderstanding, which can lead to hostile attribution bias.21,45,60 This bias causes victims to doubt the intentions of others and only trust those who have also experienced victimization, further exacerbating their feelings of isolation and lack of support.57 That’s why more emotional adaptation problems were reported by those victims in a class which is generally perceived to be positive.

According to the social standardization effect, individuals tend to align with the group gradually over time, influenced by the group’s norms and values. In a negative context where instances of bullying are more common, individuals may become accustomed to such behavior, potentially leading to a higher tolerance for bullying.12,13,17,18

Implications

The discovery that students who experience bullying may exhibit heightened emotional distress in a healthy classroom environment compared to an unfavorable one has significant implications for educators and school administrators. This finding indicates that merely fostering a positive and supportive classroom atmosphere may be insufficient in mitigating the detrimental effects of bullying on students’ mental well-being. Consequently, educational institutions and educators should consider devising more targeted interventions that cater specifically to the requirements of students who have endured bullying. Proactive measures should be taken to actively identify and address potential instances of bullying, even within seemingly healthy contexts. Additionally, awareness and education programs should be implemented to promote the understanding of the healthy context paradox among students. By incorporating this concept into the curriculum, students can develop a greater appreciation for the importance of respecting and supporting bullying victims. Parents, as key stakeholders in their children’s lives, should also play an active role in addressing this issue. They need to cultivate a heightened sensitivity and awareness towards it. Moreover, parents should strive to impart social skills, empathy, and conflict resolution techniques to their children, equipping them with the necessary strategies to navigate relationships and respond appropriately to such situations. In the realm of counseling, professionals should adopt rigorous and comprehensive assessment methods to increase awareness of the potential for bullying within the healthy context paradox. This entails gathering detailed background information, thoroughly understanding the individual’s real-life environment, and examining their social relationships. Students themselves should be encouraged to seek help from trusted adults, such as teachers or parents, when they experience bullying. Sometimes, bystanders may not offer help not because they do not want to, but because they are unsure of the specific reasons or how to provide assistance. Similarly, Adopting an appropriate perspective on bullying holds paramount importance as it may effectively prevent the occurrence of the healthy context paradox. In summary, the implications of this finding underscore the necessity for a multi-dimensional approach to tackling bullying in educational context settings, one that acknowledges the intricate and diverse experiences of victimized students.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations in the current study that should be acknowledged. Firstly, data variance is difficult to avoid as the variable “level of classroom victimization” in this study represents the environmental level, but was collected through self-reported measures. This methodological limitation has resulted in a variance between the environment and the individual. Secondly, “level of classroom victimization” was introduced in confirming the “healthy context paradox” and lacks empirical support in this field. Thus, further research is required to provide more evidence and references.Thirdly, this cross-sectional analysis did not allow for testing the causal relationship between individual victimization and emotional adaptation. It is unclear whether students experienced emotional problems after being bullied, or if they were more likely to be victimized because they already had emotional problems. Therefore, future longitudinal studies are needed to examine the cause-and-effect relationship.Thus, future studies conducted in a more culturally and ethnically diverse context are encouraged to be done, more sophisticated measurement techniques can be employed, and more of empirical evidence is produced.

Conclusion

The present study indicated that students may report more emotional problems in a healthy context with lower level of classroom victimization when they experienced increased victimization. While it is important to confirm the “healthy context paradox”, this finding will not directly improve the current situation. The implications of the current study suggest that traditional perceptions of the school environment may not be sufficient to address the “healthy context paradox”. Instead, educational efforts are needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. By focusing on the environmental perspective, the current study provides a deeper understanding of how the school environment affects the mental well-being of students and offers potential interventions. These findings highlight the importance of addressing the complex interplay between individual victimization and the mediating effect of “school belonging” on emotional distress in healthy school environments. Overall, the current study sheds light on a unique and important phenomenon and underscores the need for continued research and educational efforts to support the mental health of students in diverse contexts.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Psychology, Yangtze University. The informed consent process was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the committee, and all participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study. This research adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

The key projects of education science plan of Hubei Province in 2022: Study on the influencing factors and intervention mechanism of non suicidal self injurious behaviors in adolescents (2022GA030), and the Major Project for Philosophy and Social Science Research of Hubei Province (23ZD132). The Key Projects for Philosophy and Social Science Research of Department of Education of Hubei Province in 2022(22D035).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Olweus D. Bullying at school long-term outcomes for the victims and an effective school-based intervention program. In: R L editor. Aggressive Behavior. The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology;1994. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9116-7_5

2. Zhu X, Yang X, Zhang X, Liu Q. The effect of teacher-student relationship on middle school students being bullied: the mediating role of school belonging. Adv Psychol. 2021;11(04):910–918. doi:10.12677/ap.2021.114104

3. Zhang W, Xu J, Shen L, Wei H. The problem of bullying in schools--some basic facts we know. J Shandong Normal Univ. 2001;3:3–8. doi:10.16456/j.cnki.1001-5973.2001.03.001

4. Wang J. The relationship between middle school student bullying victimization and school membership: The moderating effect of the school climate. [Master’s thesis]. Hunan Normal University, China; 2018.

5. Zhang Y. Study on the relationship among peer relationship, sense of school belonging, school bullying of middle school students. [Master’s thesis], Southwest University, China; 2020.

6. Wang N. The relationship between bullying and friendship quality in middle school students: A study of self-esteem’s mediation and intervention. [Master’s thesis]. Shanxi Normal University, China; 2019.

7. Lyndal L, Bond L, Carlin J, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G. Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ. 2001;323:480–484. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7311.480

8. Khatri P, Kupersmidt JB, Patterson C, Griesler PC. Aggression and peer victimization as predictors of self-reported behavioral and emotional adjustment. Aggressive Behavior. 2000;26(5):345–358. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(2000)26:5<345::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-L

9. Eyuboglu M, Eyuboglu D, Pala SC, et al. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2021;297:113730. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113730

10. Kyriakides L, Creemers BPM, Papastylianou D, Papadatou-Pastou M. Improving the school learning environment to reduce bullying: an experimental study. Scand J Educ Res. 2014;58(4):453–478. doi:10.1080/00313831.2013.773556

11. Bradshaw CP, Evian Waasdorp T, Lindstrom Johnson S. Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: influence of school context. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(3):494–508. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.893516

12. Garandeau CF, Lee IA, Salmivalli C. Decreases in the proportion of bullying victims in the classroom. Int J Behavioral Develop. 2016;42(1):64–72. doi:10.1177/0165025416667492

13. Huitsing G, Snijders C, van Duijn MAJ, Veenstra R. The healthy context paradox: victims’ adjustment during an anti-bullying intervention. J Child Family Stud. 2019;28:2499–2509. doi:10.1007/s10826-018-1194-1

14. Lleras C. Hostile school climates: explaining differential risk of student exposure to disruptive learning environments in high school. J Sch Violence. 2008;7(3):105–135. doi:10.1080/15388220801955604

15. Bellmore AD, Nishina A, Witkow MR, Graham S, Juvonen J. Beyond the individual: The impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims’ adjustment. Develop Psych. 2004;40(6):1159–1172. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159

16. Yun HY, Juvonen J. Navigating the healthy context paradox: identifying classroom characteristics that improve the psychological adjustment of bullying victims. J Youth Adolescence. 2020;49(11):2203–2213. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01300-3

17. Liu X, Pan B, Li T, Zhang W, Salmivalli C. How does classroom environment impact the victims’ adjustments? Healthy context paradox and its mechanisms. Psycho Develop Edu. 2021;37(2):298–304. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.02.17

18. Huang Y, Gan X, Jin X, et al. The healthy context paradox of bullying victimization and academic adjustment among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 2023;18(8):e0290452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0290452

19. Melendez-Torres GJ, Warren E, Ukoumunne OC, Viner R, Bonell C. Locating and testing the healthy context paradox: Examples from the INCLUSIVE trial. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2022;22(1):57. doi:10.1186/s12874-022-01537-5

20. Liu Z, Zhu R, Cui H, Huang Z. Emotional regulation: report on the study on social and emotional skills of Chinese adolescence (II). Adv Psychol. 2021;11(09):47–61. doi:10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2021.09.003

21. Zhang W, Ji L, Li T, Chen L, Pan B, Liu X. Healthy context paradox in the association between bullying victimization and externalizing problems: the mediating role of hostile attribution bias. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2021;53(2). doi:10.3724/sp.J.1041.2021.00170

22. Wei Y. The relationship between external developmental assets and emotional adaptation in junior high school students: the mediator role of internal developmental assets [Master’s thesis]. Shandong Normal University, China; 2016.

23. Whitney I, Smith PK. A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educational Research. 1993;35(1):3–25. doi:10.1080/0013188930350101

24. Baldry AC. The impact of direct and indirect bullying on the mental and physical health of Italian youngsters. Aggressive Behavior. 2004;30(5):343–355. doi:10.1002/ab.20043

25. Zhao S. Study on conditions and relationship among school belonging, self-efficacy and interpersonal relation of the middle school students. [Master’s thesis], Hebei Normal University, China; 2012.

26. Chen X. Research on the relationship among senior high school students’ sense of school belonging, depression and anxiety: mediating role of mental resilience. [Master’s thesis], Central China Normal University, China; 2019.

27. Maslow AH. A dynamic theory of human motivation. In: Stacey CL, DeMartino M editors. Understanding Human Motivation. Howard Allen Publishers; 1958:26–47. doi:10.1037/11305-004

28. Goodenow C, Goodnow. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychol Schools. 1993;30:79–90. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

29. Weiner B, Frieze I, Kukla A, Reed L, Rest S, Rosenbaum RM. Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In: Jones EE, Kanouse DE, Kelley HH, Nisbett RE, Valins S, Weiner B, editors. Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987:95–120.

30. Cheng W, Guan Y, Luo Y. Campus bullying and sense of belonging to school and campus security among high school students: a cross-sectional survey. Chin J Public Health. 2020;36(6):889–894. doi:10.11847/zgggws1124168

31. Arslan G. School bullying and youth internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Do school belonging and school achievement matter? Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;1–14. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00526-x

32. Dong H, Zhang W, Kuang H, Liang G, Li L. Peer aggression and emotional adaptation in mid- and late childhood: the mediating role of attribution. Studies Psychol Behav. 2017;5:654–662.

33. Li L, Chen H, Sun Y. Junior school students’ victimization and peer relationships: mediating effect of core self-evaluation. In:

34. Bao K, Xu Q. Preliminary study on school belonging of school students. Psychol Exp. 2006;2:51–54. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2006.02.012

35. Yue D. Correlations between different relational-based social supports and emotional adjustment among adolescents. [Master’s thesis]. Shanxi Normal University, China; 2014.

36. Furlong MJ, You S, Renshaw TL, Smith DC, O’Malley MD. Preliminary development and validation of the social and emotional health survey for secondary school students. Soc Indic Res. 2013;117(3):1011–1032. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0373-0

37. Ladd K, Ettekal I, Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Rudolph A. Children’s coping strategies: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization? Develop Psych. 2002;38(2):267–278. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.267

38. Schacter HL, Juvonen J. The effects of school-level victimization on self-blame: Evidence for contextualized social cognition. Develop Psych. 2015;51(6):841–847. doi:10.1037/dev0000016

39. Yan Y, Tian L, Wang L, Tian S, Zhang D, Zhou J. The effect of cyberbullying on adolescents’ mental health: the mediating role of peer relationship stress. In:

40. Ren P, Zhang Y, Zhou Y. The positive participant role in school bullying: the defenders. Adv Psych Science. 2018;26(1):98–106. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00098

41. Yang C, Sharkey JD, Reed LA, Chen C, Dowdy E. Bullying victimization and student engagement in elementary, middle, and high schools: Moderating role of school climate. School Psychol Quat. 2018;33(1):54–64. doi:10.1037/spq0000250

42. Liu L, Zhai P, Wang M. Parental harsh discipline and migrant children’s anxiety in China: The moderating role of parental warmth and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Viol. 2021. doi:10.1177/08862605211037580

43. Huitsing G, Veenstra R, Sainio M, Salmivalli C. ”It must be me” or ”it could be them?” The impact of the social network position of bullies and victims on victims’ adjustment. Social Networks. 2012;34(4):379–386. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2010.07.002

44. Gaffney H, Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggr Violent Behav. 2019;45:111–133. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

45. Sijtsema JJ, Rambaran AJ, Ojanen TJ. Overt and relational victimization and adolescent friendships: selection, de-selection, and social influence. Social Influ. 2013;8(2–3):177–195. doi:10.1080/15534510.2012.739097

46. Zhang J, Wu Y, Kevin Jones K. Revision of the Chinese version of the Olweus child bullying questionnaire. Psycho Develop Edu. 1999;15(2):7–11, 37.

47. Gregory A, Cornell D, Fan X, Sheras P, Shih T-H, Huang F. Authoritative school discipline: High school practices associated with lower bullying and victimization. J Educ Psychol. 2010;102(2):483–496. doi:10.1037/a0018562

48. Auerbach SM, Spielberger CD. The assessment of state and trait anxiety with the Rorschach test. J Pers Ass. 1972;36(4):314–335. doi:10.1080/00223891.1972.10119767

49. Fang J, Wen Z, Wu Y. The analyses of multilevel moderation effects based on structural equation modeling. Adv Psych Science. 2018;26(5):781–788. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00781

50. Xiong Y, Wang Y, Wang Q, Wang H, Ren P. Can lower levels of classroom victimization be harmful? Healthy context paradox among Chinese adolescents. J Interpersonal Viol. 2022;38:2464–2484. doi:10.1177/08862605221102482

51. Xiao M. Emotion regulation self-efficacy and depressive mood: the mediating role of emotion regulation strategy. [Master’s thesis], Northwest Normal University, China; 2015.

52. Schachter S. The interaction of cognitive and physiological determinants of emotional state. In. 1964;49–80. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60048-9

53. Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, Flament C. Social identity and inter-group behavior. Social Sci Inf. 1974;13(2):65–93. doi:10.1177/053901847401300204

54. Wright JC, Giammarino M, Parad HW. Social status in small groups: individual-group similarity and the social ”misfit”. J Pers Social Psych. 1986;50(3):523–536. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.523

55. Sentse M, Scholte R, Salmivalli C, Voeten M. Person-group dissimilarity in involvement in bullying and its relation with social status. J Abnormal Child Psych. 2007;35(6):1009–1019. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9150-3

56. Raschke HJ. The role of social participation in postseparation and postdivorce adjustment. J Divorce. 1978;1(2):129–140. doi:10.1300/J279v01n02_04

57. Lerner MJ, Miller DT. The Belief in a Just World. Perspectives in Social Psychology. Boston, MA: Springer; 1980. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5_2

58. Pan B, Li T, Ji L, Malamut S, Zhang W, Salmivalli C. Why does classroom-level victimization moderate the association between victimization and depressive symptoms? The “Healthy Context Paradox” and two explanations. Child Devel. 2021;92(5):1836–1854. doi:10.1111/cdev.13624

59. Zhao Q, Li C. Victimized adolescents’ aggression in cliques with different victimization norms: The healthy context paradox or the peer contagion hypothesis? J School Psychology. 2022;92:66–79. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2022.03.001

60. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychil Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306

61. Edwards J, Caplan R, Harrison V. Person-environment fit theory: conceptual foundations, empirical evidence, and directions for future research. In: Cooper CL, editor. Theories of Organizational Stress. Oxford University Press; 1998:28–67.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.