Back to Journals » Journal of Asthma and Allergy » Volume 17

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Childhood Asthma in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia

Authors Gohal G , Yassin A , Darraj H , Darraj A, Maghrabi R, Abutalib YB, Talebi S, Mutaen AA, Hamdi S

Received 28 October 2023

Accepted for publication 15 January 2024

Published 20 January 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 33—43

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S443759

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Luis Garcia-Marcos

Gassem Gohal,1 Abuobaida Yassin,2 Hussam Darraj,3 Anwar Darraj,3 Rawan Maghrabi,3 Yumna Barakat Abutalib,3 Sarah Talebi,3 Amani Ahmed Mutaen,3 Sulaiman Hamdi3

1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia; 3Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Gassem Gohal, Email [email protected]

Background: The prevalence of asthma among children has been on the rise worldwide, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Our study was conducted to determine the prevalence of asthma and its related risk factors among school-age children in the Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Method: The study was a cross-sectional prospective study that used Phase I ISAAC protocol and was conducted from March to June 2023. The sample size was calculated to be 1600 among school-age children in the Jazan Region Saudi Arabia. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 23.0, Descriptive statistics were calculated for study variables, and appropriate tests of significance were performed to determine statistical significance.

Results: The total study population was 1368 the majority of them, 96.6% (n=1321), were Saudi nationals, and most of them lived in rural areas (70.6%, n=966). The prevalence of life-long wheezing, wheezing in the last 12 months, and exercise-induced wheezing was 28.0%, 29.2%, and 30.9%, respectively. Risk factors such as having indoor plants, having a pet, and a smoker in the household were reported by 48.0%, 24.6%, and 36.4% of participants, respectively. Living near an industrial area was determined as a risk factor in 98 (7.2%) of the children. Asthma-related symptoms were strongly correlated with all risk factors based on the chi-square test, and some risk factors based on multivariate linear regression.

Conclusion: The prevalence of asthma among children in the Jazan Region is higher than previously reported, and the reported risk factors are significantly correlated with symptoms of asthma.

Keywords: asthma, children, epidemiology, risk factors, Jazan Region, prevalence, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

It’s alarming to note that the prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of childhood asthma have increased significantly over the past four decades. Despite being the most common chronic disease among children, underdiagnosis and undertreatment remain major concerns. The prevalence of asthma symptoms among children varies significantly across the globe, with up to a 13-fold difference between countries.1 Both children and adults worldwide have a variable prevalence of asthma, ranging from 1–20%. This variation in prevalence can be attributed to different epidemiological definitions of asthma, the use of various measurement methods, and environmental differences between countries.2 Although rural areas tend to have a lower incidence of asthma, this is because factors associated with traditional rural lifestyles protect against allergic diseases. In contrast, numerous exposures related to urbanization have been identified as potential risk factors for asthma.3 Unfortunately, most asthma-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

The prevalence of asthma is high in both children and adults in Saudi Arabia (SA). According to the Saudi Initiative for Asthma (SINA 2016), the prevalence of asthma in children ranges from 8–25%. This increase in prevalence is due to several factors such as improved living standards, rapid modernization, and increased rates of urbanization.4 Studies have shown that the highest prevalence of asthma in Saudi children is in Hofuf (33.7%), Najran (27.5%), and Madinah (23.6%), while the lowest prevalence is in Abha (9%), Qassim (3.2%), and Dammam (3.6%), a center for the Saudi oil industry located on the Arabic Gulf.5 The studies show that multiple factors contribute to the high rate of asthma prevalence. These include changes in lifestyle and urbanization, as well as socioeconomic status and dietary habits. Additionally, exposure to indoor animals, allergens, dust, tobacco smoke, sandstorms, and industrial and vehicular pollutants can also play a role. While the location of residences has been identified as a factor, more research is needed to determine the impact of climate on asthma prevalence.6 Determining whether recurrent wheezing during the first years of life represents a clinical manifestation of future asthma is a challenge that can facilitate decision-making in clinical practice and the issue of guidance relating to specific preventive measures.7

The measurement of asthma-related symptoms in children and adolescents is mainly based on the International Study on Asthma and Allergy in Children (ISAAC), which aims to standardize the methodology and promote global collaboration for epidemiological research on asthma and allergic disease. The ISAAC protocol involves three phases, with the first phase utilizing core questionnaires to evaluate the prevalence and severity of asthma and allergic disease in specific populations.8

The prevalence of asthma and asthma-related symptoms in Saudi Arabia has been increasing in recent years and has been attributed to various environmental factors. These include the rapid industrialization of the country, which has led to the establishment of numerous factories in the industrial city of Baysh, located about 60 km north of Jazan city. Other factors include the proximity of farms to housing, traffic-related air pollution, frequently encountered sandstorms, and family awareness of asthma symptoms. It is recommended that periodic assessments of the prevalence of asthma and its associated risk factors be conducted to develop effective prevention and control strategies.6 The current study aims to investigate the prevalence of asthma and asthma-related symptoms and related risk factors among school-age children in the Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

This study was conducted in the Jazan Region, one of the thirteen regions of SA. Located on the tropical Red Sea coast in southwestern Saudi Arabia, Jazan covers an area of 11,671 km2 and includes approximately 5000 villages and cities, with a total population of 1.5 million. Geographically, the region is divided into three areas - coastal, plain, and mountain - which are intersected by perennial rivers. These geographical factors may have an impact on the prevalence of bronchial asthma (BA) in the region.

Study Design

To fulfill the proposed objectives, the study utilized a cross-sectional design and administered the ISAAC questionnaire to school-age children in Jazan Region, SA. The questionnaires were completed during a three-month period starting from March 2023.

Sample Size

The primary objective of the research was to estimate the prevalence of BA among school children in the Jazan Region of SA. To this end, the researchers employed multistage cluster random sampling. The sample size for estimating the prevalence of BA among school children in Jazan was determined using Cochran’s formula, targeting a 95% confidence level and 5% precision based on a 15.1% anticipated prevalence rate. The final count of 1690 children accounts for anticipated non-responses and is stratified by the geographical regions, ensuring representativeness across different geographic areas and gender. Detailed calculations and considerations for the design effect and sample adjustment are available in the Appendix 1. The sample was evenly distributed between areas, education level (elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools), and both sexes, according to the sex ratio of the participating schools. Schools and students in the different clusters were chosen using a simple randomization technique, and the sample was distributed among the three geographical areas as 355, 1050, and 285 participants for coastal, plain, and mountain regions, respectively.

Data Collection

The researchers used the ISAAC - Phase I Questionnaire, which is a validated Arabic version, to evaluate the prevalence of asthma and asthma symptoms in children and adolescents. The questionnaire was used in a worldwide multicenter study that assessed the prevalence and severity of asthma in children from different populations.9 The study randomly selected children between the ages of 5 and 18 years. The questionnaire is divided into four sections, each with questions that analyze different aspects of the study’s goals. The first section collected data on the child’s age, gender, place of residence, level of education, and body mass index (BMI). The second section recorded asthma-related symptoms as defined by the ISAAC manual. Life-long wheeze was defined as wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past including wheezing due to cold, chest infection, or bronchitis. Wheezing in the chest in the last 12 months refers to the presence of whistling or wheezing sounds in the chest during the past 12 months. Moreover, exercise-induced wheezing was defined as the occurrence of wheezing or shortness of breath during or after exercise. Past medical history of BA is considered whether the individual has ever been diagnosed with asthma by a doctor or other health professional.

The third section contained six questions to determine the relationship between the prevalence of asthma and various risk factors. Finally, the fourth section contained seven questions to assess the risk of asthma among children and adolescents. The questionnaires were sent electronically by the academic advisors in the selected schools to the parents of the selected students who were accepted to participate in the study. The parents filled out the questionnaire based on their selected child for the study. The medical history and risk factors were reported in the questionnaire by the parents. The academic advisors played a great role in distributing the survey and following them regularly till reached the target response from the study population, which was 85% of the sample size.

Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 23.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to enter and analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the study variables, including frequency and percentage for qualitative variables and mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables. Appropriate tests of significance such as chi-square and t-tests were performed, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted before the main study to evaluate participants’ understanding of the survey used for data collection. The pilot study accounted for 10% of the required sample size. Specific improvements were made and some questions were reordered based on the pilot study results. It’s worth noting that the results of the pilot study were not included in the final data analysis.

Statement of Ethics

The Jazan University’s Scientific Research Ethics Committee (R.E.C) approved the study with the reference number REC-44/03/334. The study was conducted in adherence to SA’s ethical principles and the Declaration of Helsinki. Before completing the anonymous questionnaire, informed consent was obtained from each participant. The informed consent is taken in two steps, the first one is by academic advisors in the schools by sending an official email and message through WhatsApp to the parents of selected students to inform them about their children’s participation in the study. The second step for those who accept their children to participate in the study, is by sending the survey link via WhatsApp, the informed consent embedded in the cover page of the survey. If the parents click on the accept icon, that means they accept their children to be enrolled in the study. The participants had the freedom to withdraw from the survey at any point during the research process. The privacy and confidentiality of the participants were maintained as none of the answers contained information that could reveal their identity. Additionally, all information was kept confidential and only accessed for specified research purposes (Appendix 2).

Results

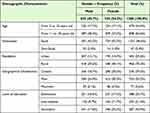

The study collected a total of 1368 questionnaires out of 1690 that were distributed to students in the Jazan Region. The response rate of the study was 91.2%. The study found that out of the respondents, 1321 (85.0%) were Saudi nationals, with 743 (54.3%) females and 625 (45.7%) males. The mean age of the participants was 12.98 ± 4.447 years, and the median age was 14 years. The majority of the participants, 966 (70.7%), lived in rural areas, while 402 (29.6%) lived in urban areas. In terms of geography, most of the participants, 755 (55.2%), lived in the plain area, while only 77 (5.6%) lived in the mountain area. The study also revealed that the distribution of students based on their education level was as follows: elementary 488 (35.7%), intermediate 293 (21.4%), and secondary 587 (42.9%). The distribution of students based on their education level is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Background Characteristics of the Study Population |

The data presented in Table 2 illustrates the prevalence of BA-related symptoms among the students. Out of all the students, 383 (28.0%) were found to have symptoms suggestive of life-long wheezing. Interestingly, females accounted for 58.7% of those with life-long wheezing, and the difference in prevalence between male and female students was statistically significant (p = 0.040). Additionally, the prevalence of exercise-induced wheezing and wheezing during the last 12 months was found to be 423 (30.9%) and 400 (29.2%), respectively. Furthermore, the study found that 27.5% (n= 377) of the student population had a medical history of BA, with no significant difference in frequency between males and females (p = 0.379). Out of the students with a medical history of asthma, 88.9% (335) had confirmed asthma diagnosis from a doctor.

|

Table 2 Prevalence of BA-Related Symptoms |

Table 3 provides an overview of various risk factors and their frequencies in relation to the outcome variable. The odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values allow for an assessment of the strength and significance of the associations.

|

Table 3 Risk Factors |

According to the table, the presence of plants in the house is the most common risk factor with a prevalence rate of 48.0% among all participants. The OR for the presence of a plant was 0.890, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.719–1.101. The p-value associated with this risk factor was 0.453, indicating that there was no statistically significant association between the presence of a plant and the outcome variable. Similarly, the presence of a smoker at home had a frequency of f 36.4% among all participants with OR indicating a strong relationship as a risk factor, but this association was without statistical significance (p-vale=0.159. The presence of a pet in the house (cat, dog, bird) was found to be a risk factor for 24.6% of the participants. Living near an industrial area was identified as a risk factor in only 7.2% of the students. Body mass index was also found to be a significant risk factor in relation to gender.

Table 4 presents a comprehensive analysis of the correlation between background characteristics, risk factors, and the prevalence of bronchial asthma (BA)-related symptoms in the study population, with statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05. The findings underscore the complex interplay of demographic factors and risk elements in shaping the prevalence of BA-related symptoms, providing valuable insights for tailored intervention strategies.

|

Table 4 Correlation Between the Prevalence of Asthma-Related Symptoms, Some Background Chrematistics and Asthma Risk Factors |

Life-long wheezing showed varying prevalence across demographic factors, with higher rates in the plain area (10.4%) compared to coastal (5.2%) and mountain (2.1%) areas. Rural locations had a higher prevalence (10.8%) than urban areas (6.9%), but these differences lacked statistical significance. No significant variations were observed based on nationality and education level.

Wheezing in the last 12 months exhibited significant associations with age group, nationality, and educational level (p-values 0.002, 0.028, and 0.001, respectively). The 11–18 age group reported higher wheezing frequency (17.4%) compared to the 5–10 age group (11.8%). Saudi nationals experienced wheezing more frequently (28.7%) than non-Saudis (0.5%). Elementary school students had a higher prevalence (12.0%) than those in intermediate and secondary schools.

Exercise-induced wheezing significantly varied by geographic area, with the plain area reporting the highest occurrence (18.2%). However, other background characteristics did not show statistical correlation. Most reported risk factors exhibited a significant statistical relationship with asthma-related symptoms, as indicated by odds ratios greater than 1.0 and p-values less than 0.05, except for life-long wheezing, presence of plants in the house, history of BA, and living near an industrial area.

Table 5 presents the results from the multiple linear regression model for the predictors of the prevalence of BA-related symptoms, which revealed a strong statistically significant relationship between symptoms and having at least one parent with a history of asthma and the presence of a smoker in the household. Having a pet at home was a trigger factor for life-long wheezing (95% CI 0.003–0.142, p = 0.002). Other risk factors were not considered as a trigger for asthma symptoms in the study population based on the returned p-values.

|

Table 5 Correlation Between Prevalence of Asthma-Related Symptoms and Asthma Risk Factors Based on Linear Regression |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of asthma-related symptoms among school-aged children using the ISAAC protocol. The ISAAC phase I methodology was a global initiative that involved collaboration to investigate the patterns and causes of asthma.10 It is the most extensive international survey ever conducted on the prevalence of asthma symptoms.11 The ISAAC phase I methodology was straightforward, and the protocol was rigorously enforced. Several validation studies have indicated that the ISAAC core questions on wheezing had appropriate sensitivity and specificity when compared to other indicators of asthma, such as physician diagnosis, other questionnaires, and physiological measures.12

A total of 1368 students, with a mean age of 12.98 ± 4.447 years old and ranging from 5–18 years were screened using the Arabic translation of the ISAAC phase I questionnaire. More female students than males participated in the study (54.3% vs 45.7%). In this respect, the study population differs from a similar study using the same methodology conducted in Jazan Region in 2017,9 and another study conducted in the Taif area.13

The prevalence of life-long wheezing was 28.0% (n=383). Females accounted for 58.7% of those with life-long wheezing, with a clear statistically significant difference in prevalence according to gender (p = 0.040). This rate is higher than has been reported by similar studies in Jazan Region in 2017 (17.7%)9 and in 1995 (23.0%),14 as well as other regions of SA including Rabigh (23.0%), Taif area (13.4%), Ahad Rubaida (9.5%), Najran (27.5%), Riyadh (19.6%), Madinah (15.5%), Makkah (24.0%),15 Riyadh (17.7%), Jeddah (14.1%), Alkhobar (9.5%), and Abha (9.0%).5,13,16–23 The rate is lower than was reported by a similar study in Hofuf (33.7%).21 The prevalence of other asthma-related symptoms, wheezing in the last 12 months, and exercise-induced wheezing in the last 12 months were 29.2 and 30.9, respectively, with the female predominance of 54.3% and 56.0%. Female predominance of asthma-related symptoms prevalence is strikingly different from the previous study in Jazan Region,9 and other local studies.17,20,24,25

Compared to neighboring Gulf countries, the prevalence of lifelong wheezing is higher in this region. Kuwait, Sultanate Oman, and Bahrain reported a prevalence of 11.9%,21 12.7%,22 and 10.8%,23 respectively,26–28 which is lower than the prevalence in Qatar (34.6%),29 and the United Arab Emirates with 44.2% for the age group 6–7 years and 33.1% for the age group 13–14 years.30 Globally, the prevalence of asthma among school children ranged from 1.1% (Lucknow, India) to 23.2% (Costa Rica),31 which is lower than the reported prevalence in the current study.

According to a study, the prevalence of asthma was higher among students living in rural areas (20.5%) than those in urban areas (7.5%), but the difference was not statistically significant. Another study conducted in SA showed that the prevalence of asthma in urban and rural children was 13.9% and 8%, respectively.9 The current study found that students living in mountainous areas reported more symptoms than those who lived in plain and coastal areas, with prevalence rates of 39%, 27.7%, and 21.3%, respectively.

According to the current study, nearly 29.2% of individuals experienced exercise-induced wheezing, while about 30.9% of them reported wheezing in the last 12 months. Interestingly, these numbers are relatively higher than the results of the previous study in Jazan, which recorded the prevalence of exercise-induced asthma and wheezing in the past year at 14.7% and 11.4%, respectively.9 Additionally, among the students with a medical history of BA, 27.6% reported experiencing it, which is much higher than the 15.1% recorded in the previous Jazan study.9 However, the rate of physician-diagnosed asthma in the Jazan Region increased from 10.0% in the previous study9 to 24.5% in the current one, indicating a positive trend of seeking medical advice for asthma management and control of symptoms.

The questionnaire sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing students with BA-related symptoms were 78.8%, 76.7%, and 78.2% for life-long wheezing, wheezing in the last 12 months, and exercise-induced wheezing in the last 12 months, respectively. This means that 78.8% of those who reported life-long wheezing actually had asthma. On the other hand, the specificity was 88.5%, 86.2%, and 84.4% for life-long wheezing, wheezing in the last 12 months, and exercise-induced wheezing in the last 12 months, respectively, indicating that 88.5% of those who did not report any symptoms did not have asthma. Interestingly, the sensitivity of the questionnaire in the current study was much higher compared to the previous Jazan study (65.9%), while the specificity remained the same.9

Asthma-Related Risk Factors

It’s true that there are several triggers that can cause acute asthma attacks, which can be classified into three categories: indoor, outdoor, and occupational sensitizers. All of these risk factors have been linked to asthma and the varying distributions of these risk factors may account for the differences in prevalence.10

The current study indicates a close correlation between asthma-related symptoms and the following risk factors: the presence of plants, pets, or smokers in the house, family history of asthma, BMI > 25, and living near an industrial area (p < 0.05). Moreover, the prevalence of the co-existence of risk factors in students with asthma-related symptoms is less than reported by similar studies in Riyadh25 and Taif13 for all identified risk factors except the presence of plants in the home.

Smoking is considered a major risk factor for asthma development during childhood. Smoking by a family member has a positive impact on asthma prevalence rate among asthmatic children compared to non-asthmatic. This clearly indicates that increased tobacco exposure increases the incidence of asthma by irritation of the inflamed bronchial airways.11 The positive association between smoking and asthma from this study is consistent with local,12,14,22,32 and global studies.11,33–37

Air pollution is a significant concern for global health, as it is a risk factor for numerous respiratory conditions that can lead to morbidity and mortality. Over the years, research has shown that air pollution can worsen pre-existing asthma conditions. However, recent studies suggest that air pollution may also cause new-onset asthma.38 Primary pollutants are directly released into the environment, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, methane, and black carbon. Secondary pollutants, on the other hand, are formed through chemical reactions in the atmosphere between primary pollutants, such as ozone, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, sulfur trioxide, nitrates, and sulfates.39 Jazan has become one of the most industrialized regions in SA, following the development of Jazan economic city at Baysh for transformative industries. Industrialization has led to an increase in air pollution, which may result in a higher prevalence of respiratory diseases, particularly asthma. The findings of the current study are similar to a study conducted in Riyadh, where school children in Riyadh North had the highest rate of asthma among their peers in other areas of the city, while Riyadh South had the lowest rate. This discrepancy may be due to increased aeroallergens in Riyadh North, such as those found in farms, the industrial zone, Riyadh International Airport, and the airbase.25 Studies have shown that environmental exposure plays a crucial role in the development of tolerance to ubiquitous allergens found in natural environments.40 Other sources of outdoor air pollution are sandstorms and the presence of farms near housing. In the present study, most of the population lived in rural areas, which are mainly agricultural. Many studies have established that aeroallergens and sandstorms play a substantial role in aggravating asthma and other allergic diseases.41

Indoor pets have been found to significantly increase the risk of allergic diseases, including asthma, rhinitis, and skin allergy, in families that have them compared to those without pets, according to a study.42,43 Obesity is known to be a major risk factor and a disease modifier of asthma in children and adults.44 Obese children have a one-third higher risk of developing asthma than children of healthy weight.45 However, in the current study, only 13.8% of those with life-long wheezing had a BMI higher than 25, which is lower than other local studies.13,25 Based on our findings, BMI can be considered a risk factor for asthma, with a significant difference in gender (p-value=0.011).

Limitations

The study that used the ISAAC protocol to measure the prevalence of asthma-related symptoms among children has some significant limitations. For instance, the study relied solely on data collected from children and their families, which may have been affected by inaccurate recall of some information, especially those related to asthma/asthma-related symptoms events that took place some time ago. Additionally, it was difficult to exclude other factors that can cause wheezing apart from BA. As a result, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution. However, it is worth noting that the prevalence rates of childhood asthma/asthma-related symptoms in Jazan Region have increased compared to those reported by the previous study conducted in the region in 2017.

Conclusion

To conclude, it appears that the prevalence of asthma among school-age children in Jazan Region is higher than what was previously reported by other local and regional studies. Notably, students residing in plain and rural areas seem to be more susceptible to asthma compared to those living in other areas. The study found a strong correlation between risk factors and asthma-related symptoms, which highlights the need for further interventions. To identify the full extent of asthma prevalence among children, it is recommended to conduct more studies with larger sample sizes and explore more risk factors.

Acknowledgments

Our deep thanks to the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University, for supporting this study. We also acknowledge the leaders of selected schools and academic supervisors in Jazan Region for facilitating data collection. Our acknowledgments are also extended to participants and their families.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Serebrisky D, Wiznia A. Pediatric asthma: a global epidemic. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):1–6. doi:10.5334/aogh.2411

2. Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy. 2004;59(5):469–478. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x

3. von Hertzen LHT, Haahtela T. Disconnection of man and the soil: reason for the asthma and atopy epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):334–344. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.013

4. Al-Moamary MS, Alhaider SA, Idrees MM, et al. The Saudi Initiative for Asthma - 2021 update: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma in adults and children. Ann Thorac Med. 2021;16(1):4–56. doi:10.4103/atm.ATM_697_20

5. Alahmadi TS, Hegazi MA, Alsaedi H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of asthma in children and adolescents in rabigh, Western Saudi Arabia. Children. 2023;10(2):1–15. doi:10.3390/children10020247

6. Hussain SM, Ayesha Farhana S, Alnasser SM. Time trends and regional variation in prevalence of asthma and associated factors in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. vol. 2018. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2.

7. Alfonso J, Pérez S, Bou R, et al. Asthma prevalence and risk factors in school children: the RESPIR longitudinal study. Allergol Immunopathol. 2020;48(3):223–231. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2019.06.003

8. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483–491. doi:10.1183/09031936.95.08030483

9. Khawaji AF, Basudan A, Moafa A, et al. Epidemiology of bronchial asthma among children in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;31:69–75.

10. Stern J, Pier J, Litonjua AA. Asthma epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(1):5–15. doi:10.1007/s00281-020-00785-1

11. Haley KJ, Lasky-Su J, Manoli SE, et al. RUNX transcription factors: association with pediatric asthma and modulated by maternal smoking. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;310:5.

12. AlFrayh A. Asthma patterns in Saudi Arabian children. J R Soc Health. 1990;110(3):98–100. doi:10.1177/146642409011000309

13. Hamam F, Eldalo A, Albarraq A, et al. The prevalence of asthma and its related risk factors among the children in Taif area, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Sci. 2015;4(3):179. doi:10.4103/2278-0521.171436

14. Al Frayh AR, Shakoor Z, ElRab MOG, Hasnain SM. Increased prevalence of asthma in Saudi Arabia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86(3):292–296. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63301-7

15. Harthi SA, Wagdani AA, Sabbagh A, et al. Prevalence of Asthma Among Saudi Children in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5(1):1209–1214.

16. Ali Imam S. Study of the prevalence rate of bronchial asthma among the secondary schools students in Ahad Rubaida City, district Abha, Assir Region, Saudi Arabia. Imp J Interdiscip Res. 2016;2:e1362.

17. Alqahtani JM. Asthma and other allergic diseases among Saudi school children in Najran: the need for a comprehensive intervention program. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(6):379–385. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2016.379

18. Al Ghobain MO, Amms A-HMS, Al Moamary MS. Asthma prevalence among 16- to 18-year-old adolescents in Saudi Arabia using the ISAAC questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):239. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-239

19. Nahhas M, Bhopal R, Anandan C, Elton R, Sheikh A. Prevalence of allergic disorders among primary school-aged children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia: two-stage cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):1–9.

20. SalmanAAl H, AbdulrahmanSAl W, AbdulrahmanY S, AdelMAl G, IbrahimHAbu D. Prevalence of Asthma Among Saudi Children in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5(1):1209–1214.

21. Al Frayh AS. A 17 Year Trend for the Prevalence of Asthma and Allergic Diseases Among Children in Saudi Arabia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(2):S232. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.938

22. Al-dawood K. Epidemiology of bronchial asthma among school boys in AlKhobar City, Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. 2001;22(1):61–66.

23. Alshehri MA, Abolfotouh MA, Sadeg A, et al. Screening for asthma and associated risk factors among urban school boys in Abha city. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(11):1048–1053.

24. Al Ghobain MO, Al-Hajjaj MS, Al Moamary MS. Asthma prevalence among 16- to 18-year-old adolescents in Saudi Arabia using the ISAAC questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):239.

25. Horaib YF, Alamri ES, Alanazi WR. The Prevalence of Asthma and Its Related Risk Factors among the Children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;70(6):965–973. doi:10.12816/0044345

26. Ziyab AH. Prevalence and risk factors of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema and their multimorbidity among young adults in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–10. doi:10.1155/2017/2184193

27. Al-Busaidi NH, Habibullah Z, Soriano JB. The asthma cost in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13(2):218–222. doi:10.12816/0003226

28. Al-Sindi H, Al-Mulla M, Bu-Saibaa A, Al-Sharaf B, Jawad JS, Karim OA. Prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in children aged 6–7 in the Kingdom of Bahrain. J Bahr Med Soc. 2014;25(2):71–74. doi:10.26715/jbms.25_2_2

29. Hammoudeh S, Hani Y, Alfaki M, et al. The prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema among school‐aged children in Qatar: a global asthma network study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57(6):1440–1446. doi:10.1002/ppul.25914

30. Ibrahim NM, Almarzouqi FI, Al Melaih FA, Farouk H, Alsayed M, AlJassim FM. Prevalence of asthma and allergies among children in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional study. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14(10):100588. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100588

31. Asher MI, Rutter CE, Bissell K, et al. Worldwide trends in the burden of asthma symptoms in school-aged children: global Asthma Network Phase I cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1569–1580. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01450-1

32. Matsumoto I, Araki H, Tsuda K, et al. Effects of swimming training on aerobic capacity and exercise induced bronchoconstriction in children with bronchial asthma. Thorax. 1999;54(3):196–201. doi:10.1136/thx.54.3.196

33. Blekic M, Kljaic Bukvic B, Aberle N, et al. 17q12-21 and asthma: interactions with early-life environmental exposures. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110(5):347–353. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.01.021

34. Wang MF, Kuo SH, Huang CH, et al. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, human E-cadherin C-160A polymorphism, and childhood asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(4):262–267. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.07.008

35. Robison RG, Kumar R, Arguelles LM, et al. Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy, Prematurity and Recurrent Wheezing in Early Childhood. Pulmonol Pediatr. 2012;47(7):666–673.

36. Rosa MJ, Jung KH, Perzanowski MS, et al. Prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, environmental tobacco smoke and asthma. Respir Med. 2012;105(6):869–876.

37. Der Voort AMM S-V, De Kluizenaar Y, Jaddoe VWV, et al. Air pollution, fetal and infant tobacco smoke exposure, and wheezing in preschool children: a population-based prospective birth cohort. Environ Health. 2012;11(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-1

38. Chatkin J, Correa L, Santos U. External environmental pollution as a risk factor for asthma. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022;62(1):72–89. doi:10.1007/s12016-020-08830-5

39. Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, Cowl CT, et al. Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: a review by the forum of international respiratory societies’ environmental committee, part 1: the damaging effects of air pollution. Chest. 2019;155(2):409–416. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.042

40. Wang DY. Risk factors of allergic rhinitis: genetic or environmental? Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(2):115–123. doi:10.2147/tcrm.1.2.115.62907

41. Haddadi Y, Khawaji A, Basudan A, et al. Allergic rhinitis among children, Jazan region Saudi Arabia. Role Environ Fact. 2017;5(1):74–82.

42. Al-Mousawi MS, Lovel H, Behbehani N, et al. Asthma and sensitization in a community with low indoor allergen levels and low pet-keeping frequency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(6):1389–1394. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.005

43. Bener A, Mobayed H, Sattar HA, et al. Pet ownership: its effect on allergy and respiratory symptoms. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;36(8):306–310.

44. Peters U, Dixon AE, Forno E. Obesity and Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1169–1179.

45. Mayor S. Obesity is linked to increased asthma risk in children, finds study. 2018. BMJ. 363:218AD.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.