Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 16

Exploring the Peer Leadership Network of Rehabilitation Healthcare Professionals Following Leader Development Training

Authors Becker ES

Received 3 November 2023

Accepted for publication 16 January 2024

Published 25 January 2024 Volume 2024:16 Pages 39—52

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S443203

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Pavani Rangachari

Emily S Becker1,2

1Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA; 2College of Graduate Studies, ATSU, Mesa, AZ, USA

Correspondence: Emily S Becker, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The researcher aimed to identify how rehabilitation professionals engage in their peer leadership network during the first year following leader development training for the purpose of understanding the networking experiences, development of the peer leadership network, and expansion of collective leadership in an organization.

Methodology: A sequential exploratory mixed method design including Q-Methodology and focus group interviews identified the experiences of 11 rehabilitation professionals in an urban rehabilitation hospital during the first year following leader development training.

Findings: Three themes were identified. These include: (a) an opportunity to connect, (b) a community of leaders, and (c) a healthy peer leadership network emerged from the data analysis. These results indicated that shared experiences and opportunities to connect in a robust peer leadership network can influence the growth of all leaders independent of their current leadership or networking competency. The opportunity to connect for shared discussions in a healthy peer leadership network can accentuate the learning following leader development curriculum as individual leaders develop leadership and as collectives advance organizational outcomes.

Practical Implications: Healthcare organizations should facilitate connections in a healthy leadership network to develop individual and collective leadership in an organization.

Keywords: leadership, leadership development, healthcare, peer leadership network

Introduction

Strong leadership is imperative for organizations to navigate the ever-changing healthcare environment. Developing effective leaders and collaborative collective leadership are essential strategies for healthcare organizations.1 Though research has identified the networking behaviors that leaders use to shape their social networks2 and a framework for how these networks influence the development of individual and collective leadership in an organization3 little is known regarding which networking behaviors leaders use following leader development training, how these networking experiences influence the development of the peer leadership network, and what networking experiences contribute to the development of the collective leadership in an organization.4,5

This study aims to provide a deeper understanding of the networking behaviors and experiences of rehabilitation professionals during the first year following leader development training. The researcher seeks to identify what networking behaviors rehabilitation professional implement to build their peer leadership network and explore how the experiences in their social network builds collective leadership in an organization. This social network analysis was undertaken to explore the connectively, strength, and outcomes of the peer leadership network and the leadership collective as potential contributors to long-term outcomes of leadership development in a rehabilitation services organization.

Literature Review

Formal training can be effective for increasing leaders’ knowledge and skills; however, training alone does not achieve the deep level changes required for long-term and sustained growth of leadership development.6,7 Leadership development is the learning beyond leader competencies into lasting leadership outcomes such as changing mental models, interpreting a variety of experiences, and effectively collaborating in the collective leadership of an organization.8,9 Leadership development is a social process that occurs in the social networks of an organization.8

Social networks influence the leader’s development through the behaviors and experiences within the networks in an organization.10 Networking behaviors include strategies for building, maintaining, leveraging, and transitioning relationships.11 While these networking strategies are consistent across various types of networks, the leader’s engagement and activities in the social network can be influenced by the participants role, gender, related outcomes, perceptions of leadership in the context of their work, and the leaders’ autonomy and agency within an organization.4

One type of social network is the peer leadership network. The peer leadership network is an autonomous connection of leaders around shared interests, commitments, work, or information. It is vital to the development of individual and collective leadership in an organization.12 The peer leadership network is an informal network of blended social and leader relationships built on trust and mutual respect through a series of experiences in the network. Following leader development training, the leader and the peer leadership network mutually shape the individual’s leadership development and the development of collective leadership in an organization.4

A leader’s engagement in their network influences their success as a leader and the collective success of an organization.4 Leaders can learn to successfully engage in their social network through education, practice, and feedback.11 These network-enhancing approaches have been shown to improve the leadership capacity of the individual and the capacity of the collective leadership in an organization.10

Collective leadership is the organized exchange among leaders, teams, and their social networks through active connections of trust, mutual respect, and understanding.5 Collective leadership is a complex and multilayered social construct in the organization or social context in which it occurs.8,10 These interdependent, multiple layered networks of leadership support the complex modern organizational structures that are increasingly more collaborative and decentralized in structure.10

Collective leadership is created through developing individual leaders, forming relationships, networking across the organization, and coordinating actions among workgroups through the extension of the social network in the organization.8 The development of individual leaders and collective leadership networks influence each other through the exchange of information and goals that are embedded in the network’s structure and communication.9

Conceptual Framework

Cullen-Lester et al3 provided a framework for how social networks influence the process of moving from leader competency into leadership development of individuals and collectives in an organization. This framework includes three approaches for leadership development (1) developing individual social competence, (2) shaping individuals’ networks, and (3) cocreating collective networks. Once initial competency for intrapersonal and intrapersonal communication is achieved, approaches for developing an individual’s networks can be deployed. Concurrent to this process for the individual, social networks are forming to develop of the collective leadership in an organization.

Though this framework illustrates an approach to developing individual and collective leadership in a social network, little research is available to identify which networking behaviors leaders implement to develop their peer leadership network.4,9 Currently, little is known regarding the influence of networking experience on leadership development or how the peer leadership network influences the development of the collective leadership.5,13 While much work has focused on improving human capital related to leadership competency, there is an emerging opportunity to understand the social capital and networking experiences that influence leadership development.11,14

Sarpy and Stachowski12 suggested future leadership research include social network analysis to examine the effects of leader development programs on network development and organizational outcomes. By examining the connectivity, health, and outcomes of the peer leadership network following leader development training, the influence of training on the development of the individual leader and collective leadership in an organization can be better understood.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify the networking experiences of rehabilitation professionals during the first year following leader development training. The researcher explored how rehabilitation professionals engage in their peer leadership network to influence the development of the individual and collective leadership following leader development training.

Research Question

Research Question 1: What are the networking behaviors of rehabilitation professionals following leader development training?

Research Question 2: How do rehabilitation professionals experience their peer leadership network to build collective leadership in an organization following leader development training?

Methodology

This sequential exploratory mixed-methods design including Q-Methodology and focus group interviews was implemented to explore the experiences of rehabilitation professionals in the peer leadership network during the first year following leader development training. Q-Methodology has been identified as an ideal method to study leadership development1 as it can identify and quantify the social experiences of a collective. The Q-Methodology in this study provided the frequency of collective experiences and behaviors within the social network. In keeping with best practices in Q-Methodology and social network analysis, a mixed methods research design was implemented to provide additional information not available when using only one of these methods. The semistructured focus groups were chosen to capture the interactions, attitudes, and experiences of the collective within the social setting.15 The interactions in the focus groups elicited information regarding the quality, connectivity, health, and net outcomes of the experiences of the collective in the peer leadership network.

Sample

Rehabilitation professionals in a large urban rehabilitation hospital 1 year following participation in a standardized national curriculum for leadership development were recruited for this study. Participants had a professional title of physical therapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), or speech-language pathologist (SLP), participated in the same offering of the leader development curriculum, and were employed in the same institution over the same timeframe. Participants from other professional disciplines, clinicians with additional previous degrees in management or leadership, direct reports, and participants from other offerings of leader development curricula were excluded from participation in this study. Based upon the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14 participants were eligible to participate. All eligible participants were contacted via their work email for voluntary participation.

Instrumentation

In Q-Methodology, participants are given a set of statements called the Q-set. While the number of statements in a Q-set is not limited, a 30–40 statement Q-set is considered ideal to balance statistical power and participant engagement in the study.16 Participants rank the statements in the Q-set through a process called the Q-sort. The statistical power in Q-Methodology is determined by the number of items in the Q-set rather than the number of individuals that participate in the Q-sort.16

Q-Methodology in this study was implemented using the 30 networking behaviors identified by Cullen-Lester et al2 as the Q-set. The Q-Methodology was followed by semistructured focus groups interviews. The researcher-designed moderator guide for these semistructured interviews consisted of questions established for social network analysis by Hoppe and Reinelt15 and questions developed following Q-sort.

Q-Methodology is considered a reliable and valid assessment tool because it represents an individual’s point of view.17 Using previously established networking statements and interview questions provided additional validity and reliability. The researcher attempted to limit bias and support validity and reliability by eliciting a content expert to review language changes, implementing member checking following focus groups, and incorporating triangulation through reviewing participant feedback surveys following the leadership course.

Data Collection

The data were collected 1 year after leader development training. Following IRB approval, eligible participants received an emailed link including informed consent, online Q-sort, and schedule to participate in one of four Zoom focus groups. Using online Q-Methodology software,18 participants arranged the 30 networking behaviors into three categories (1) implemented often, (2) sometimes implemented, or (3) did not implement over the past year. The participants sorted the responses into subcategories by frequency of use for each behavior across a preestablished 9-point quasinormal bell-shaped curve with the right-most column labeled “most frequently used” (+4), left-most column labeled “least frequently used” (−4), and a neutral response in the center of the distribution (0). Subjects were then scheduled to participate in participated in one of four focus groups conducted through the Zoom online platform.

Data Analysis

Sample Description

Thirteen of the 14 eligible participants completed the Q-Methodology portion of the study; however, two participants did not participate in the study’s focus groups resulting in 11 out of 14 participants completing both portions of the study (see Table 1).

|

Table 1 Participant Demographics |

Research Question 1: What are the networking behaviors of rehabilitation professionals following leader development training?

The Q-Method software18 was used to assist the researcher in analyzing the data. The Q-sorts were reviewed. No errors or incomplete sorts were detected. The researcher applied Pearson’s correlation matrix as a standardized measure of linear association between the scores. Next, the researcher chose factor extraction analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) based on the classification in learning and the potential for multicollinearity between the variables. These collective responses were then reviewed to create additional questions for the focus groups.

Research Question 2: How do rehabilitation professionals experience their peer leadership network to build collective leadership in an organization following leader development training?

The focus group data collected were transcribed by the Zoom platform, downloaded into the NVivo qualitative software program, and text errors updated with brackets to indicate changes made in the text. The exploratory factors identified from the Q-Methodology were then used as deductive codes in the initial analysis of the focus group data. Following the deductive coding, open coding was performed to identify additional codes and codes were grouped to make connections across the data. Open coding resulted in four nodes. No additional codes were found during the analysis of the final two focus groups indicating saturation had been reached. Codes were collapsed to represent salient themes.

Results

Research Question 1: What are the networking behaviors of rehabilitation professionals following leader development training?

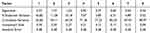

The factor extraction of the Q-Methodology produced eight principal components (see Table 2). A significant factor loading at the 0.01 level was calculated using the following equation: 2.58(1/√30). This resulted in a correlation of 0.47 or greater. Three factors that achieved this level ranged between 0.48–0.87. The three factors that met this level also met the Kaiser-Guttman criterion for inclusion. The three extracted factors explained 64.29% of the total variance and each accounted for at least 10% of the variance individually. Additionally, the drop-off in eigenvalues and review of the scree plot supported the retention of these three factors.

|

Table 2 Determination for Factor Rotation |

Varimax rotation of these three factors resulted in the Q-sort values and z-scores for each factor (see Table 3). Factor loadings were then reviewed for negative and bipolar associations, non-confounding factor loadings and nonsignificant factor loadings, and for covariance, commonality, and hyperplane percent. The covariance among the three variables ranged from −0.03–0.09, indicating little relationship among variables. Communality ranged from 0.57–0.79, indicating that the extracted factors may explain more of the variance than an individual item.

|

Table 3 Factor Scores for Networking Behaviors |

The latent constructs of the three factors derived from the Q-Methodology were identified for answering Research Question 1 and included as deductive codes in the analysis of the focus group data. First, most characteristic and quite characteristic statements for each factor were identified. Then, each networking behavior was identified as one of four types: (a) building, (b) maintaining, (c) leveraging, and (d) transitioning. The type of networking behaviors for each of these characteristic statements was determined and used to name the factors based on the meaning of their latent constructs. The latent constructs of these factors were (1) actively seeking opportunities, (2) relationship centered networking, and (3) networking for personal development. Table 4 includes each factor and the networking behaviors most characteristic or quite characteristic unique to that factor.

|

Table 4 Networking Behaviors for Each Factor |

Factor 1: Actively Seeking Opportunities in the Organization

Actively seeking opportunities across the organization was associated with maintaining (n=5/42, 42%) and leveraging (n=5/12, 42%) network strategies to coordinate the participants’ work across the organization. This factor includes bonding activities in the current collective and bridging behaviors to extend the network outside the current collective network. The most common networking strategies included both two-way directed bonding engagements and one-way directed bridging activities to link in the extended collective-level network. Based on the inclusion of collectives exhibiting strong tendencies to build in their network and leverage outside of the network, this factor is closely aligned with Approach 3: Collectives Co-creating Networks in the Cullen-Lester et al3 conceptual framework.

Factor 2: Relationship-Centered Networking

Relationship-centered networking was associated with building (n=3/12, 25%) and maintaining (n=6/12, 50%) networking strategies in and external to the organization. The strategies identified establish new connections with undirected network connections and deepen connections with two-way directed connections in the collective. The network behaviors in this collective are primarily bonding as they are building and maintaining the connections in the collective. This factor most closely aligns with Approach 2: Individuals Shaping Their Networks in the Cullen-Lester et al3 conceptual framework.

Factor 3: Networking for Personal Development

Personal development was associated with building (n=4/12, 33%) and maintaining (n=5/12, 42%) networking strategies. The most characterizing networking behaviors associated with this factor were directed one-way or undirected networking activities with influence at the individual level. These factors align with Approach 1: Individuals Developing Competence in the Cullen-Lester et al3 conceptual framework.

Research Question 2: How do rehabilitation professionals experience their peer leadership network to build collective leadership in an organization following leader development training?

Codes reported in two or more focus groups with at least five instances in each transcript were ranked according to their frequency. The most frequently identified codes were shared learning (n = 67, 14.2%), informal social connections (n = 39, 8.3%), regularly scheduled activities (n = 31, 6.7%), meetings (n=28, 5.9%), expanding network (n = 28, 5.9%), support and encouragement (n = 27, 5.7%), investment in relationships (n = 21, 4.4%), shared understanding (n = 21, 4.4%), the effect of COVID on networking (n = 20, 4.2%), and variety of perspectives (n = 20, 4.2%). Each factor identified in the Q-sort was represented in the most frequently identified codes. The thematic analysis supported the span of experiences across each of the approaches in the Cullen-Lester et al3 conceptual framework.

Themes

The researcher identified three themes through the open coding process. These themes include the opportunity to connect, a community of leaders, and outcomes of a healthy peer leadership network (see Table 5).

|

Table 5 Opportunity to Connect |

Opportunity to Connect

Every focus group identified the importance of an opportunity to connect. Participants mentioned a variety of formal activities such as meetings, small group activities, learning partners, team retreats, and professional conferences. The participants also recognized the importance of informal connections such as having discussions after formal meetings, eating lunch together, or engaging in social relationships outside of work. These events provided an opportunity to connect and engage with each other for shared discussions.

Informal social connections were the most frequently mentioned opportunity to connect with others. The informal social discussions motivated these leaders to grow and eased their efforts when subsequently engaging in the professional context. As one participant shared,

It’s social, but it really is very much like professional networking, too…people getting to know each other on a deeper level and allowing them to then later approach each other much more easily.

Many leaders mentioned discussions with learning partners and small groups as opportunities for learning. One participant shared, “The small groups have been sharing a space for professional growth”. Participants identified that these discussions were important learning opportunities as they were not overly complicated, did not require preparation, and were highly applicable to relatable circumstances. Both individuals connecting for personal mentorship and groups connecting for shared discussions were highly valued experiences for these leaders.

Participants also valued the time to connect and discuss during formal meetings, retreats, and conferences. As one participant shared,

We talk about an off topic. But that’s our chance to connect… that’s really the micro networking pieces that are so valuable.

Other teams included a standing agenda item provided as a constant reminder for leadership development. The standing agenda item created an opportunity to share and build leadership without the need for an additional meeting. Professional conferences provided opportunities for informal discussions for participants to expand connections in their professional network. In all circumstances, the after-meetings discussions were mentioned as the most important opportunities to create connections with different leaders both inside and outside their organization.

The leadership development course was another opportunity to connect for expanding personal growth and relationships in the peer leadership network. While all participants agreed that a strong core network has been sustained since the leadership course, some members recognized that continued connections are necessary to maintain the strength of the network. “I’m not sure how we’re gonna keep it going, if we don’t have an annual check-in, or something. Everyone has great intentions, but it’s just you get busy”. Another informal opportunity to connect that the participants mentioned that they greatly missed was eating lunch together. Not eating lunch together was identified as a limitation for connection with team members throughout 2022 due to continued COVID precautions at that time.

Throughout the focus groups, participants shared multiple ways in which they fostered continued connections. Each of these events offered leaders the opportunity to discuss, share, connect, and build relationship with other leaders. These formal or informal experiences in their networks created their peer leadership network and developed the collective leadership in an organization.

Community of Leaders

A community of leaders was another theme extracted from the focus group data (see Table 6). This high-trust community provided individuals, dyads, and the collective leadership opportunities for growth through support and advice sharing among its members. This supportive culture was evident throughout the focus groups in the participants’ words and their interactions. Many participants were complimentary, supportive, encouraging, and interested in others’ perspectives throughout the focus group discussions. The participants reported that they frequently reached out to others as a resource and also provided support to others with their own strengths as well. One participant reported, “[It] also really helps to have connections with people who might have a little bit of a different role than you to help you gain a different perspective”.

|

Table 6 Community of Leaders |

Participants reported that sharing advice about professional development and personal experiences helped them grow as leaders. “[Sharing professionally] as well as what they’re doing in life, and what their interests are. It helps us all”. Advice sharing and support were identified between individual leaders and groups of leaders in the collective. As one participant shared,

I think [it’s] people building off of the relationships they have in place or just informally [connecting with] other people. It made it even more personal making those strong relationships.

Independent of the leaders’ stages of leadership development, a community for support and sharing advice was a valued characteristic among all members in this learning community.

Participants identified location and the frequent changing of teams related to the great resignation as limitations in building a community. The great resignation was a mass voluntary quitting of employees starting early 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic that greatly affected healthcare. The high number of resignations and subsequent role transitions during this time limited the leaders’ ability to create and maintain connections among team members. Location was also mentioned as a limitation to growth. Network locations were described as “isolating” and limited the engagement and connection in the peer leadership network.

While location was a factor, participants shared the strong, people-first culture across their organization. One participant noted,

People are so invested in forming healthy and strong relationships with each other. And then it makes me want to do that for other people. Those relationships have been really instrumental [in] helping me [with] advancing my career and [my] confidence [as a] whole.

The participants shared this culture was evident not only in their peer leadership network, but in the entire leadership of the organization. This supportive culture provided positive network experiences and a strong community for individual and collective leadership to grow throughout the organization.

Outcomes of a Healthy Peer Leadership Network Following Leader Development Training

Participant responses indicated a very healthy peer leadership network (See Table 7). Every focus group identified the strength and health of the peer leadership network through increased trust, connectivity, and diversity following the leader development course. The enriched engagement following leader development training expanded the effect of the network through greater collaboration and coordination among its leaders. This strong and healthy peer leadership network provided a positive context for growth following the leader development course.

|

Table 7 Outcomes of the Peer Leadership Network |

The peer leadership network increased job satisfaction and network outcomes such as improved coordination, collaboration, and connections in the organization. As one participant shared,

And how terrible would it be if we didn’t have…a strong …and healthy relationship…for me, my job satisfaction depends on [it].

Every focus group agreed that coordination, collaboration, and network connectivity increased as a result of the shared learning in the leader development course. The leader development course provided a connection that was later expanded upon later in the organization which improved information sharing between members with varied expertise.

Participants shared that the course created connections and gave them additional skills to engage in their social network. As one participant stated,

[My network is] healthier and stronger than it was before and maybe its’s just that I have a confidence to communicate what I need or have different … and more skills that [now] I can go to people more. [sic]

Another participant reflected on their experience by sharing “[The course] has opened up more doors. It’s beyond the network that I would have imagined”.

This supportive and diverse community expanded the knowledge and experience all leaders engaged in this peer leadership network during the first year following leader development training. Whether individuals were trying to grow their network, dyads were seeking to maintain their network, or the collective was leveraging its network to expand connections, all participants consistently identified these themes during the focus groups. As stated by one participant,

And so I think overall it was helpful in growing the network, but also [the] quality of the people in the network, and the quality of the relationships in those in the network. [sic]

Discussion

These results identify that shared experiences and opportunities to connect in a healthy learning community can influence the growth and development of all leaders. The three themes were independent of the individual’s current leadership competency or phase of leadership development. Leaders who were learning competencies for beginning to engage in their social network, those who were currently building or maintaining their networks, and those who were engaging in the collective leadership to leverage internal and external networks all recognized the opportunity to connect in a healthy peer leadership network contributed to their increased functionality in the organizational structure. The opportunity to connect in a healthy network community can accentuate the learning following leader development curriculum as individual leaders progress in their development and as collectives advance organizational outcomes.

These findings highlight that all stages of leadership benefit from shared learning, experiences, and the opportunity to connect in the peer leadership network. This community for learning provided professional and personal support, advice, and shared discussions amongst the group. These results support that leadership can be taught through a variety of methods including formal education, mentorship, and leadership experiences.19 Hoppe and Reinelt15 previously identified that shared work led to a greater connection in a leadership collective. The results of this study further identified that the informal discussions around the shared work in a supportive, open, and diverse peer leadership network created this opportunity for strengthening the collective leadership.

This research supports social-network and social-relational theories of leadership development in demonstrating a growth in leadership and collective leadership following leader development training.4,9 These findings further support Lieff et al4 in identifying the importance of personal and professional networking activities following leader development training. The findings of this study corroborate those of McCauley and Paulus8 who shared that the peer leadership network elevates and sustains the growth of the individual leader as part of the development of the organization’s collective leadership.

These findings align with previous research that identified a supportive community as a key factor in the development of leaders and the peer leadership network.12 This supportive community may not only be important in the development of the peer leadership network, but is also a mutually influencing contextual factor impacting the development of the individual leader’s identity and leadership self-efficacy. Becker et. al20 expanded these findings by identifying a supportive relationship as the most important best practice for facilitating mentorship outcomes. The findings from these studies suggest that the proximal indicators of leadership development including psychological safety, knowledge of team members expertise, and shared learning/mindsets for collectives continue to be important distal outcomes of leadership development.

The positive experience in the leadership network also contributed to increased job satisfaction, enhanced network connectivity, and expanded collaboration and coordination of work for improved organizational outcomes. Similar findings identified the importance of peer relationships in knowledge sharing, job performance, and overall organizational satisfaction.14 Floyd et al21 and Gerbasi et al22 further validated the findings of this study in connecting the importance of the peer network and collective leadership to the leader’s overall satisfaction, self-efficacy, and leadership outcomes.

While this study aligns with the Cullen-Lester et al3 framework for leadership development, the inclusion of the three study themes across all three factors which aligned with the stages of leadership development in the Cullen-Lester et al3 framework suggests a more fluid, less linear process between individual and organizational outcomes. The fluid and overlapping results following leader development training in this study may more closely align with a conceptual model proposed by Hofmann and Vermont.23 Hofmann and Vermont’s23 model includes overlapping individual and organizational outcomes following clinical leader development training. This model highlights the importance of engaging in interprofessional dialogues to improve overall organizational outcomes of collaboration and coordination to speed up practice change and innovation. As in both conceptual models, the results of this study supports that leader development training and subsequent network experiences can be a mechanism of growth for both individual and system outcomes. The experiences in the peer leadership network facilitates the growth of individual leaders and creates the collective leadership within an organization. These reported perceptions may indicate long-term changes following leader development training of increased collective leadership and improved organizational outcomes. The healthy community in the peer leadership network created personal and professional connections amongst all leaders. This connection was shown to be an important for factor for the development of individual leaders, development of the collective leadership, and the expansion of the overall outcomes of the organization.

Limitations

While all focus groups were originally scheduled with greater than four participants in each session, last minute participant schedule changes resulted in focus groups of varying sizes which unintentionally altered discussion time for each participant across the groups Additionally, these data represented a small sample of rehabilitation leaders at one facility during the time of COVID and the great resignation. These unique circumstances may limit the generalizability of the results to other organizations and other time periods in the observed organization.24 As more is learned about the effects of the COVID pandemic on the healthcare workforce, the findings of this study may be contextualized differently considering those outcomes.

Additionally, analyzing these data based upon the demographic information may have been beneficial. During the analysis of the focus groups, it became apparent that work location limited engagement in the peer leadership network. Additionally, many studies have demonstrated the influence of gender on professional networking.11,25 If the demographic information would have been available to connect to each Q-sort, hand rotation of the data could have been performed to determine quantitative differences based upon the participants’ work location or gender.

Participant and researcher bias may limit these results. While the participants familiarity with the researcher may have increased their comfort throughout the focus groups, it could have introduced acquiescence, social desirability, habituation, and sponsorship bias. Though the researcher attempted to limit the influence of biases throughout the study there is always opportunity for bias to influence results shared though research.

Recommendations

Researchers should investigate proximal and distal changes in the leadership network, collective leadership, and organizational culture following leader development training. Researchers should conduct longitudinal studies to investigate how collective leadership shapes the individual leader’s development, as well as how the autonomy and self-efficacy of individual leaders drive the leaders to shape their own social networks. The interdependencies and cross-network effects of multiple social networks on the development of leadership and collective leadership in an organization should be explored.

Conclusions

The experiences of rehabilitation professionals in their peer leadership network following leader development training were explored. Results of this study indicated that the opportunity to connect for informal discussions in a healthy community of leaders can advance the growth of both individual leaders and the collective leadership in an organization. Learning in the social context augments the learning from leader development training through both continued individual and collective leadership development which ultimately impacts the organization’s functionality.

All leaders in this peer leadership network benefited from participation in the shared leadership course. By training a collective group of leaders, this education and experience allowed individuals to progress in their leadership development and for the peer leadership network to grow the collective leadership in the organization. As the leaders and collectives progressed in their development, the connectivity and engagement in their social network expanded through informal discussions and intensified communal support. These social interactions in their peer leadership network moved the learning beyond the proximal outcomes of leadership training into potentially more long-lasting distal outcomes of leadership development.

Organizational outputs can be improved when all leaders independent of their current leadership competency participate in shared leader development training. Organizations should seek to provide additional opportunities for shared discussions in a healthy community for learning to support leadership development beyond formal leader competency training. By providing these opportunities, healthcare organizations will expand the development of their peer leadership networks and the collective leadership for improved organizational outcomes across their systems of influence.

Ethical Statement

The proposal was reviewed by the ATSU Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine IRB and found to be in the exempt category according to 45CFR46.104 (d)(2)(ii). The IRB Number is EB20220829-001.

Informed consent in this study included publication of anonymized responses as stated within the consent process which included the wording: “You understand that the results of the research study may be published but that your name or identity will not be revealed and that your records will remain confidential…. The information will be de-identified before publication and throughout the dissemination process. Careful consideration including de-identification and quote selection during the dissemination”.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Day DV, Fleenor JW, Atwater LE, Sturm RE, McKee RA. Advances in leader and leadership development: a review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadersh Q. 2014;25(1):63–82. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004

2. Cullen-Lester KL, Woehler ML, Willburn P. Network-based leadership development: a guiding framework and resources for management educators. J Manag Educ. 2016;40(3):321–358. doi:10.1177/1052562915624124

3. Cullen-Lester KL, Maupin CK, Carter DR. Incorporating social networks into leadership development: a conceptual model and evaluation of research and practice. Leadersh Q. 2017;28(1):130–152. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.005

4. Lieff SJ, Baker L, Poost-Foroosh L, Castellani B, Hafferty FW, Ng SL. Exploring the networking of academic health science leaders: how and why do they do it? Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1570–1577. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003177

5. Whitney JM, Henry SE, Bradley BH. Maybe it is who you know: social networks and leader–member exchange differentiation. Group Organ Manag. 2022;47(2):300–347. doi:10.1177/10596011221086327

6. Nagyo Fotso G. Leadership competencies for the 21st century: a review from the Western world literature. Europ J Train Develop. 2021;45(6/7):566–587. doi:10.1108/EJTD-04-2020-0078

7. Walker DOH, Reichard RJ. On purpose: leader self‐development and the meaning of purposeful engagement. J Leadersh Stud. 2020;14(1):26–38. doi:10.1002/jls.21680

8. McCauley CD, Palus CJ. Developing the theory and practice of leadership development: a relational view. Leadersh Q. 2021;32(5):101456.

9. Eva N, Cox JW, Herman HM, Lowe KB. From competency to conversation: a multi-perspective approach to collective leadership development. Leadersh Q. 2021;32(5):Article 101346. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101346

10. Maupin CK, McCusker ME, Slaughter AJ, Ruark GA. A tale of three approaches: leveraging organizational discourse analysis, relational event modeling, and dynamic network analysis for collective leadership. Human Relations. 2020;73(4):572–597. doi:10.1177/0018726719895322

11. Woehler ML, Cullen-Lester KL, Porter CM, Frear KA. Whether, how, and why networks influence men’s and women’s career success: review and research agenda. J Manage. 2021;47(1):207–236. doi:10.1177/0149206320960529

12. Sarpy SAC, Stachowski A. Evaluating leadership development of executive peer networks using social network analysis. Int J Leadersh Educ. 2020;19:2.

13. Piggot-Irvine E, Ferkins L, Rowe W. Leadership in action research: surfacing the collective nature of leadership. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2021;38(6):851–865. doi:10.1002/sres.2732

14. Swanson E, Kim S, Lee SM, Yang JJ, Lee YK. The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: social capital theory. J Hospital Tour Manag. 2020;42:88–96. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.11.004

15. Hoppe RC, Reinelt C. Social network analysis and the evaluation of leadership networks. Leadersh Q. 2010;21(4):600–619. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.06.004

16. D’Amato D, Droste N, Winkler KJ, Toppinen A. Thinking green, circular or bio: eliciting researchers’ perspectives on sustainable economy with Q Method. J Cleaner Prod. 2019;230:460–476. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.099

17. Cheng X, Van Damme S, Li L, Uyttenhove P. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: a review of methods. Ecosyst Serv 2019;37:100925. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100925

18. Lutfallah S, Buchanan L. Quantifying subjective data using online Q-methodology software. Ment Lexicon. 2019;14(3):415–423. doi:10.1075/mL.20002.lut

19. Channing J. How Can leadership be taught? Implications for leadership educators. Int J Leadersh Educ Leader Prepa. 2020;15(1):134–148.

20. Becker ES, Grant M, Witte MM, Deveikis LT, Traisman RK. Exploring outcomes in formal physical therapy mentorship programs. Educ Health Professions. 2023;6(1):34–41. doi:10.4103/EHP.EHP_2_23

21. Floyd TM, Cullen-Lester KL, Lester HF, Grosser TJ. Emphasizing “me” or “we”: training framing and self‐concept in network‐based leadership development. Human Resour Manage. 2023;62(4):637–659. doi:10.1002/hrm.22112

22. Gerbasi A, Emery C, Cullen-Lester K, Mahdon M. Satisfied in the outgroup: how co-worker relational energy compensates for low-quality relationships with managers. In: Understanding Workplace Relationships: An Examination of the Antecedents and Outcomes. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023:137–165.

23. Hofmann R, Vermunt JD. Professional learning, organizational change, and clinical leadership development outcomes. Med Educ. 2021;55(2):252–265. doi:10.1111/medu.14343

24. Ornell F, Halpern SC, Kessler FHP, Narvaez JC. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2020;36(4):e00063520. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00063520

25. Grosser TJ, Sterling CM, Piplani RS, Cullen-Lester KL, Floyd TM. A social network perspective on workplace inclusion: the role of network closure, network centrality, and need for affiliation. Human Resour Manage. 2022;2022:1.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.