Back to Archived Journals » International Journal of Wine Research » Volume 6

Consumers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward the role of oak in winemaking

Authors Crump A, Johnson T, Bastian S , Bruwer J, Wilkinson K

Received 1 July 2014

Accepted for publication 17 July 2014

Published 29 October 2014 Volume 2014:6 Pages 21—30

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWR.S70458

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Anna M Crump,1 Trent E Johnson,1 Susan EP Bastian,1 Johan Bruwer,1,2 Kerry L Wilkinson1

1School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, The University of Adelaide, Glen Osmond, SA, Australia; 2Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, The University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Abstract: Oak plays an important role in the production of some white wines and most red wines. Yet, consumers’ knowledge of the use of oak in winemaking and their preference for oak-related sensory attributes remains unclear. This study examined the knowledge and attitudes of 1,015 Australian wine consumers toward the use of oak in winemaking. Consumers who indicated a liking of oak-aged wines (n=847) were segmented according to their knowledge of the role of oak in wine production. Four distinct consumer clusters were identified, with significantly different preferences for wine sensory attributes and opinions regarding the use of oak alternatives for wine maturation. One segment comprised more knowledgeable consumers, who appreciate and value traditional oak maturation regimes, for which they are willing to pay a premium price. However, a segment comprising less knowledgeable wine consumers was accepting of the use of oak chips, provided wine quality was not compromised. Winemakers can therefore justify the use of oak alternatives to achieve oak-aged wines at lower price points. The outcomes of this study can be used by winemakers to better tailor their wines to the specific needs and expectations of consumers within different segments of the market.

Keywords: maturation, segmentation, wine, wine consumers

Introduction

Oak plays an important role in the production of some white wines and most red wines, affecting both physical attributes and sensory properties. The volatile compounds extracted from oak wood1–4 can contribute to a wine’s overall aroma, flavor, and complexity,5,6 while the maturation process leads to increased color and stability7 and reduced astringency.8 However, oak is an expensive raw material and barrels contribute significantly to production costs. Therefore, while barrel maturation is still preferred for the production of premium wines, the range and application of alternative oak products (eg, oak battens, chips, shavings, and powder), as more rapid and economical methods of oak treatment, has increased.9,10 The increased surface area of oak alternatives, compared to barrels, results in greater rates of flavor extraction, so both the quantity of oak and the duration of contact with wine are greatly reduced. Additionally, less oak is rejected for alternatives than for barrel cooperage, since oak with structural defects, ie, knots, cracks, or poor grain quality, is perfectly acceptable for the preparation of alternative oak products. Furthermore, the use of micro-oxygenation techniques, in conjunction with oak alternatives, also enables the introduction of small quantities of oxygen, thereby more closely replicating traditional maturation in barrels.11

Compared with traditional barrel maturation, some wine consumers may consider the use of oak alternatives to be “industrial”, which might negatively impact their perceptions of quality. A greater understanding of consumers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward different oak maturation regimes is therefore required to ascertain the acceptability of wines aged using alternative oak products.

Consumer research is often used to gain insight into consumers’ acceptance, preference, and perception of different foods and beverages; in particular, the relative influence of extrinsic and intrinsic cues, such as region of origin, packaging, branding, and sensory properties, on consumer liking and purchase intent.12 For example, a study into the effect of bottle closures on the perception of wine quality found North American wine consumers considered wine bottled under screw cap closures to be of lower quality than wine bottled under natural cork.13 The situational dependency of wine selection influences has also been investigated, with grape variety, geographical region of origin, and food matching found to be important to consumers with high levels of wine involvement.14,15 This information can be applied by industry to better tailor products to the specific needs and expectations of consumers; ie, to provide a basis for production and/or marketing strategies which target specific consumer segments.

Surprisingly, despite the importance of oak to wine production, few studies have considered consumers’ knowledge of the role of oak in winemaking or even their preference for oak-aged wines. Instead, wine-related consumer studies have tended to focus on purchase drivers, product involvement, and wine expertise.14,16–18 Lockshin and Rhodus investigated the influence of price and oak flavor on the perception of wine quality and found that consumers had no real preference for oak, whereas wine wholesalers held oak maturation in much higher regard, particularly with respect to the marketability of wine.19 A more recent study evaluated consumer preferences for wines aged in oak barrels or with oak chips.20 The authors observed considerable disparity in consumers’ wine preferences, but since consumers did not significantly reject wines made with oak chips, they concluded that markets exist for wines using both oak maturation regimes.

Winemakers are receptive to the adoption of innovative winemaking processes, including the use of oak alternatives, provided economic benefit can be demonstrated and neither wine quality nor consumer acceptability will be compromised. The objective of this study was therefore to gain insight into wine consumers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward different oak maturation regimes, in particular, consumers’ perceptions and acceptance of wines made using alternative oak products; ie, to investigate whether or not knowledgeable consumers hold traditional oak barrel maturation of wine in high regard, while less knowledgeable consumers are accepting of oak alternatives, justifying their use by winemakers for wines at lower price points.

Materials and methods

Focus groups

Focus groups were conducted to gain preliminary insight into wine consumers’ knowledge of the role of oak in winemaking, in order to inform the structure and content of a larger, more detailed consumer survey. Participants were recruited by distributing fliers to residential letterboxes in suburbs located within an 8 km radius to the west, south, and southeast of the Adelaide (SA, Australia) central business district. These suburbs were specifically chosen for their proximity to the focus group venue, and therefore increased likelihood of participation. Participants were screened against inclusion criteria comprising wine consumption at least once a month and being of legal drinking age (ie, at least 18 years of age) and exclusion criteria precluding participation by wine industry professionals and university staff and students.

Participants (12 females and 18 males, aged between 18 and 65 years) were assigned to one of three focus groups, held during May and June 2010, according to their availability. Two researchers attended each focus group, ie, a moderator and an assistant. The moderator led the focus group activities, which comprised: 1) a triangle test21 to investigate differentiation of oaked and unoaked wines (using a commercial 10 Australian dollar [AUD] Chardonnay, with and without the addition of 10 g/L toasted oak); 2) an evaluation of wine bottle labels and the relative importance of label content; and 3) a series of preprepared questions pertaining to winemaking, the role of oak in wine production, and wine purchasing behavior. Group discussions were transcribed by the assistant, with each focus group also being recorded to ensure all responses were captured. The moderator remained neutral and did not try to influence the participants or bias their responses in any way. The duration of each focus group was ~90 minutes and participants were compensated with a bottle of wine.

Consumer survey

Themes identified during the focus groups were used to develop an online consumer survey, which was administered nationally using SurveyMonkey™. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods, including social networking sites, wine blogs, local and interstate media, and national distribution of a flier. Screening was performed using the same inclusion criteria applied to focus group participants. The survey took ~10–15 minutes to complete and data were collected over an 8-month period. A convenience sample of 1,447 consumers was achieved, with a completion rate of 78% (ie, 1,128 responses). Participants residing outside Australia (n=113) were excluded, resulting in a total of 1,015 responses from Australian wine consumers.

The survey was divided into three sections. The first section comprised sociodemographic questions (Table 1), while the second and third sections explored consumers’ wine involvement and knowledge of the use of oak in winemaking.

| Table 1 Consumer demographic, consumption, and knowledge characteristics |

The second section comprised questions relating to participants’ wine purchasing and consumption behavior, incorporating questions from previous research.14 These questions were intended to ascertain how much consumers typically spend on a bottle of wine, the factors that most strongly influence their selection of wine for consumption at home, how often they read wine bottle labels, and their tendency to cellar wines. Section 3 comprised questions relating to consumers’ knowledge and opinions regarding the use of oak during winemaking (Table 2), and their liking of wine sensory attributes, including descriptors associated with oak maturation (Table 3). Questions also sought to determine consumers’ preferences for oak-aged wines and French versus American oak (Table 4). The survey required participants to give either “yes” or “no” responses or to indicate agreement or disagreement to statements using 5-point category scales, as used elsewhere.15,22 For example, the section concerning purchasing behavior required participants to indicate how strongly different factors influenced their wine purchasing decisions, again using 5-point category scales, ranging from 1, “very unlikely” to 5, “very likely” (Table 5).

| Table 4 Consumers’ preferences for oak maturation of wine |

Data analysis

Consumer data were analyzed using a combination of descriptive techniques, including analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Fisher’s test, correlation analysis, and principal component analysis. For those participants who indicated they liked oaked wines (n=847), data were also analyzed by factor and cluster analysis to allow segmentation on the basis of oak knowledge. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (v 19; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and XLSTAT 2012.1.01 (Addinsoft, New York, NY, USA).

Results and discussion

The primary objective of the focus groups was to inform the structure and content of the online consumer survey. Participants’ responses to questions pertaining to wine production, the role of oak in winemaking, and wine purchasing behavior, including the importance of information presented on wine bottle labels, varied considerably depending on factors such as sex, wine involvement, and frequency of wine consumption (data not shown), highlighting a need for segmentation of consumer data from the online survey. Participants also completed a triangle test, with oaked and unoaked Chardonnay wines presented in a balanced, randomized presentation order.21 Twenty (out of 30) consumers correctly identified the different sample (P<0.001), but only four participants attributed oak-related sensory attributes as the basis for their difference. Most participants instead used basic sensory descriptors such as bitterness, sweetness, and/or fruit intensity to describe differences between the wines. This suggests consumers readily perceived the sensory attributes associated with oak maturation, but could not adequately describe them, in agreement with an earlier study.23

Demographic characteristics of consumers

One thousand and fifteen respondents completed the online survey. A higher proportion of participants were female, ie, 63% female and 37% male (Table 1), which was consistent with previous wine consumer research.22 A relatively even distribution of consumers was obtained across the different age groups. The number of respondents with tertiary qualifications (76.8%) was greater than in the general population,24 but again consistent with other studies that demonstrated wine consumers are more likely to hold tertiary qualifications.16,25,26 This was also reflected in respondents’ household incomes; ~50% of respondents had an average household income above 100,000 AUD, with the majority of participants’ household earnings exceeding the 64,168 AUD per annum Australian median household income.27

Segmentation of wine consumers according to their oak knowledge

The wine industry has long understood the benefits of market segmentation. A number of segmentation studies involving Australian wine consumers have been reported in the literature, in which variables such as lifestyle, wine knowledge and involvement, and wine expertise were used to segment the market.14,17,18,25,28

In the current study, wine consumers’ knowledge regarding the use of oak in wine production was used to identify four distinct market segments. Consumers’ responses to 13 oak knowledge statements (Table 2) were subjected to correlation analysis, which revealed multiple coefficients >0.3. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was 0.81 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant. Principal component analysis identified three factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, which explained 28.9%, 15.2%, and 9.1% of the variance, respectively. Parallel analysis supported retention of the three-factor solution and oblimin rotation showed strong loadings with all but one of the variables from one factor (data not shown). The variable “no difference in quality” (Table 2) was excluded from further analysis as it did not load positively against any factor. Factor 1 related to the effect of oak on wine quality; factor 2 comprised consumers’ opinions toward the use of oak alternatives; and factor 3 related to the contribution of oak to wine flavor. Hierarchal cluster analysis followed by k-means cluster analysis was performed on these three factors and yielded a four-cluster segmentation solution, with the final cluster centers reported in Table 6. Subsequent discriminant analysis revealed that this solution provided a 93% accurate fit to the data.

Cluster 1 (C1), n=461

These predominantly female consumers made up the largest segment; C1 consumers indicated they “don’t care how it’s made as long as it tastes good”, but otherwise did not have strong opinions (positive or negative) to statements concerning oak quality or the use of oak alternatives. This cluster comprised the highest proportion of occasional drinkers, who typically spend the least on wine for home consumption (ie, 57.5% spend less than 15 AUD/bottle). The majority of C1 considered their wine knowledge to be limited to basic, and constituents were least likely to read the back label of a wine bottle.

Cluster 2 (C2), n=133

These consumers did not have an opinion, either positive or negative, regarding the use of oak alternatives, but they did agree that oak has an impact on the taste and quality of wine. This cluster comprised a high proportion of young consumers (with 41.4% aged 18–34 years), with moderate wine consumption and an average spend of 16–20 AUD per bottle. C2 were also the cluster most likely to read wine bottle labels.

Cluster 3 (C3), n=141

The consumers in this segment neither agreed nor disagreed that oak influences the taste or quality of wine, but they did have a moderately strong, negative opinion regarding the use of oak alternatives. This cluster was not weighted toward one sex or the other, comprised the highest percentage of older consumers (21.3% over 55 years), and were well educated, with 55.3% holding postgraduate qualifications.

Cluster 4 (C4), n=112

The consumers within this segment were predominantly male (64.3%), and considered themselves more knowledgeable about wine than consumers from other clusters, with 42.9% rating their knowledge as expert or professional. These consumers were largely frequent wine drinkers, with strong opinions regarding the impact of oak on wine quality and strong negative views on the use of oak alternatives for wine maturation. Interestingly, this cluster had no real opinion on the effect of oak on wine taste. These consumers had high average household incomes and more than one-third spend 21–30 AUD/bottle of wine for home consumption.

Consumers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward different oak maturation regimes

Within the segment of consumers who enjoy oaked wines (n=847), a large proportion of respondents answered “neither agree nor disagree” to the majority of statements relating to the use of oak in winemaking. Participants’ mean responses ranged from 2.6 to 3.5 for oak knowledge statements and from 3.0 to 3.6 for opinions concerning oak maturation (Table 2), suggesting a general lack of knowledge regarding the role of oak in wine production. Indeed, more than 10% of these consumers thought wine was always aged in oak barrels (data not shown). Sex largely did not influence participants’ perceptions of oak alternatives, but females agreed that oak alternatives were “the way of the future” slightly more than males, possibly because males perceived wines made with oak alternatives to be “cheap” (data not shown).

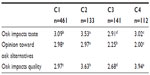

By comparison, significant differences were observed between the four clusters’ opinions regarding the maturation of wine using oak barrels or oak chips. C1 responses were similar to those of the total population; mean knowledge responses ranged from 2.83 to 3.18 and mean opinion responses ranged from 2.93 to 3.77, demonstrating the tendency of C1 to “neither agree nor disagree”. In contrast, C2, C3, and C4 responses reflected broader use of the category scale. C2 and C4 shared similar attitudes toward oak alternatives. Both clusters agreed that wines aged with oak chips are “not as socially acceptable or impressive”, are “cheap”, and “don’t sound romantic”, compared to barrel-aged wine; but C4 disagreed that “oak alternatives are the way of the future” and indicated that “production method has no influence on purchase decision”. Like C1, C3 constituents indicated they “don’t care how it’s made as long as it tastes good”. C3 generally considered oak alternatives more favorably than the other clusters; ie, they disagreed that wines made with oak chips were “cheap” and “less socially acceptable”. Interestingly, all clusters agreed the method of oak treatment should be specified on the label. This is consistent with recent work that suggests modern consumers are increasingly interested in the production, traceability, and labeling of foods and beverages.29

These results support our assertion that consumers with increased wine knowledge, ie, consumers within C4, are less accepting of alternate methods of oak maturation and hold traditional barrel maturation in higher regard. This segment comprised more knowledgeable wine consumers (42.9% rated their wine knowledge as expert or professional), with a higher disposable income (>60% have a household income above 100,000 AUD), who were willing to pay a higher premium for a quality product (>40% spend more than 20 AUD/bottle). In contrast, less knowledgeable consumers were more accepting of oak alternatives. More than 88% of consumers in C3 and 95% of consumers in C1 and C2 rated their knowledge as novice, basic, or intermediate. These clusters, in particular C1 and C3, were also more accepting of oak alternatives. C1, C2, and C3 generally purchase wines at lower price points (>80% spend less than 20/bottle AUD); ie, wines which are more likely to be matured using oak alternatives. These findings suggest winemakers are justified in using oak alternatives; ie, the target market does not consider these wines to be inferior.

Consumers’ preferences for wine sensory attributes, including oak-derived sensory attributes

Consumers were asked to rate their preferences for eleven groups of sensory attributes commonly associated with wine aroma and flavor (Table 3). The majority of sensory attributes were scored favorably by participants, ie, mean scores were ≥3.4. The exceptions were “capsicum, cut grass, eucalyptus”, “floral, rose, geranium”, and “herbaceous, earthy, tobacco, cigar” attributes, which received mean ratings of 2.78, 3.00, and 3.02, respectively, from all participants. Berry fruit attributes, ie, “blackcurrant, blackberry, strawberry, cherry”, were most preferred, with a 3.87 rating. These attributes were also preferred by each of the oak knowledge clusters (3.82–4.16). Citrus (“citrus, lemon, lime”), spice (“spicy, black pepper, licorice”), and oak (“vanilla, coconut, woody, oak”) attributes were also highly rated, while green characters (“herbaceous, earthy, tobacco, cigar” and “capsicum, cut grass, eucalyptus”) were least popular.

C1 ratings ranged from 2.81 to 3.59, ie, somewhat lower and with a smaller range than for other clusters. There was no significant difference between C2 and C3 responses, while average ratings for C4 tended to be higher than other clusters – in some cases, significantly higher. Oak attributes were favorably rated by all clusters (3.43–3.65); C4 gave oak attributes the highest scores, although scores were not significantly different between clusters. These findings are similar to those reported in a study that compared liking scores of wine consumers and wine experts, in which consumers indicated they liked “confectionary”, “floral”, “vanilla”, “red berry”, “coconut”, and “caramel” attributes (of which vanilla, coconut, and caramel are generally considered to be oak-derived), but disliked “pepper”, “smoky”, and “woody” attributes.28 In contrast, “woody” had a positive influence on wine experts’ liking scores, but experts disliked “vegetal”, “coffee”, “smoky”, and “leather” characters.

Previous studies have found that the descriptions given by novice wine drinkers usually comprise basic terms such as “sweet” or “fruity” and therefore do not enable identification or discrimination of different wines.23,30 Additionally, since certain attributes are often associated with red and white wines, for example, red wines are typically described using dark attributes (pepper, blackberry) while white wines are described using white or yellow attributes (lemon, honey),31 untrained consumers may associate these terms with specific wine styles. Thus, if they prefer white wines, for example, they may respond less favorably to those attributes typically associated with red wines.

Consumers’ preferences for oak-aged wines

The vast majority (83.4%) of participants indicated they enjoy drinking oaked wines (Table 4). Of those consumers who enjoyed oaked wines, most had no preference for wines aged with French or American oak, but where a preference was given, it was overwhelmingly in favor of French oak, while most (78.3%) did not believe they would be capable of distinguishing between wine aged in a barrel and wine aged with oak alternatives. Segmentation of these consumers into their four oak knowledge clusters allowed interesting differences between clusters’ responses to be observed. An increasing acceptance of oaked wines was observed across C1 to C4, with a higher proportion of participants responding “yes” than “sometimes”; ie, more confident responses.

The majority of participants from C1, C2, and C3 indicated no preference for French versus American oak (90.9, 78.9, and 78.0, respectively), whereas the segment most knowledgeable about oak and wine, ie, C4, indicated a strong preference for French oak (56.3%). The majority of this cluster (74%) also believed they would be able to differentiate wines based on oak maturation regimes.

The importance of oak as a purchase driver for wine consumers

Participants were asked to rate the importance of 24 intrinsic and extrinsic wine choice factors, to determine the relative influence of oak maturation on Australian consumers’ wine selection and purchasing behavior (Table 5). Prior consumption, wine style, grape variety, occasion, and price were identified as the five most important factors when selecting wine, in agreement with previous findings.14 Production method and oak treatment (ie, the use of French or American oak, new or old oak, and the duration of oak treatment) were ranked 19th and 24th, respectively, and are therefore unlikely to have any real impact on wine purchasing decisions. When specified, this information would generally be presented to consumers via the wine back label. In the current study, the majority of respondents (ie, 64%) indicated they were likely to read back label information. While the inclusion of manufacturing statements on wine labels is of interest to consumers,32 back label information has been shown to have considerably less influence on wine choice than price.25

Responses were also analyzed following segmentation according to oak knowledge. The four oak knowledge clusters also rated previous consumption, price, wine style, grape variety, and occasion as purchase drivers of considerable importance, as evidenced by mean scores ranging from 3.87 to 4.48. However, C4 rated the reputation of the winemaker (4.00) higher than price (3.96) and occasion (3.92). Wine region was an important consideration for C2, C3, and C4 (3.97–4.17), while C1 and C2 regarded recommendations from friends and family favorably (3.98 and 3.97, respectively). The segments’ self-assessed wine knowledge was reflected in their responses. C1, the segment with the least wine knowledge (Table 1), attached significantly more importance to wine brand, advertising, awards or medals, and packaging than C4, the most knowledgeable segment, who instead regarded recommendations from wine writers and the year of vintage to be of greater importance. While oak treatment and production method were not considered to be especially important purchase drivers by any of the oak knowledge clusters (2.35 to 3.25), the relative importance of these factors differed significantly between clusters, with C4 being more likely (3.25 and 2.92) to be influenced by these factors than C1 (2.51 and 2.35).

Conclusion

This study has shown that the oak maturation regime employed during winemaking has little influence on the purchasing decisions of most, but not all, consumers. Within the Australian wine consumer population, there exists a segment comprising knowledgeable consumers who appreciate and value traditional oak maturation regimes, for which they are willing to pay a premium. However, less knowledgeable wine consumers were not deterred by the use of oak chips provided wine quality was not compromised, and so winemakers can therefore justify the use of oak alternatives to achieve oak-aged wines at certain price points. Significant cost savings, in terms of both capital investment (ie, barrels) and labor associated with cellar management can be realized through the use of oak alternatives. Consumers’ responses confirmed their liking of oak-related sensory attributes, despite the fact that, in some cases, they may not have known such attributes originated from oak.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Heather Smyth from the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation for constructive discussions and suggestions, as well as the Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation (GWRDC) for research support.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Nishimura K, Ohnishi M, Masuda M, Koga K, Matsuyama R. Reactions of wood components during maturation. In: Piggott JR, editor. Flavour of Distilled Beverages; Origin and Development. Chichester: Ellis Horwood; 1983:241–255. | |

Sefton MA, Francis IL, Williams PJ. Volatile norisoprenoid compounds as constituents of oak woods used in wine and spirit maturation. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38(11):2045–2049. | |

Pérez-Coello MS, Sanz J, Cabezudo MD. Determination of volatile compounds in hydroalcoholic extracts of French and American oak wood. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1999;50(2):162–165. | |

Bozalongo R, Carillo JD, Torroba MA, Tena MT. Analysis of French and American oak chips with different toasting degrees by headspace solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1173(1–2):10–17. | |

Maga J. Formation and extraction of cis- and trans-β-methyl-γ-octalactone from Quercus alba. In Piggott JR, Paterson A, editors. Distilled Beverage Flavour: Recent Developments. Chichester: Ellis Horwood; 1989:171–176. | |

Spillman PJ, Sefton MA, Gawel R. The contribution of volatile compounds derived during oak barrel maturation to the aroma of a Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2004;10(3):227–235. | |

Pontallier P, Salagoity-Auguste M-H, Ribéreau-Gayon P. Intervention du bois de chêne dans l’évolution des vins rouges élevés en barriques. [Intervention of oak wood during barrel maturation of red wine]. Connaissance Vigne Vin. 1982;16(1):45–61. French. | |

Glories Y. Oxygen and wine aging in casks. Revue Française d’Oenologie. 1990;124:91. | |

Rankine BC. Making Good Wine: A Manual of Winemaking Practice for Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: Macmillan; 1989. | |

Fernández de Simón B, Muiño I, Cadahía E. Characterization of volatile constituents in commercial oak wood chips. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(17):9587–9596. | |

Gómez-Plaza E, Cano-López M. A review on micro-oxygenation of red wines: claims, benefits and the underlying chemistry. Food Chem. 2011;125(4):1131–1140. | |

Mueller S, Szolnoki G. The relative influence of packaging, labelling, branding and sensory attributes on liking and purchase intent: consumers differ in their responsiveness. Food Qual Prefer. 2010;21(7):774–783. | |

Marin AB, Jorgensen EM, Kennedy JA, Ferrier J. Effects of bottle closure type on consumer perceptions of wine quality. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2007;58(2):182–191. | |

Johnson TE, Bastian SEP. A preliminary study of the relationship between Australian wine consumers’ wine expertise and their wine purchasing and consumption behaviour. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2007;13(3):186–197. | |

Jaeger SR, Danaher PJ, Brodie RJ. Wine purchase decisions and consumption behaviours: insights from a probability sample drawn in Auckland, New Zealand. Food Qual Prefer. 2009;20(4):312–319. | |

Johnson T, Bruwer J. An empirical confirmation of wine-related lifestyle segments in the Australian wine market. International Journal of Wine Marketing. 2003;15(1):5–33. | |

Bruwer J, Li E. Wine-related lifestyle (WRL) market segmentation: demographic and behavioural factors. J Wine Res. 2007;18(1):19–34. | |

Chrea C, Melo L, Evans G, Forde C, Delahunty C, Cox DN. An investigation using three approaches to understand the influence of extrinsic product cues on consumer behavior: an example of Australian wines. J Sens Stud. 2011;26(1):13–24. | |

Lockshin LS, Rhodus WT. The effect of price and oak flavor on perceived wine quality. International Journal of Wine Marketing. 1993; 5(2):13–25. | |

Pérez-Magariño S, Ortega-Heras M, González-Sanjosé ML. Wine consumption habits and consumer preferences between wines aged in barrels or with chips. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91(5):943–949. | |

Meilgaard M, Civille GV, Carr BT. Sensory Evaluation Techniques. 4th ed. New York: CRC Press; 2007. | |

Barber N, Ismail J, Dodd T. Purchase attributes of wine consumers with low involvement. Journal of Food Products Marketing. 2008;14(1):69–86. | |

Parr WV, Mouret M, Blackmore S, Pelquest-Hunt T, Urdapilleta I. Representation of complexity in wine: influence of expertise. Food Qual Prefer. 2011;22(7):647–660. | |

Education and Work. Cat no 6227.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS); 2010. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/mf/6227.0. Accessed November 21, 2013. | |

Mueller S, Lockshin L, Saltman Y, Blanford J. Message on a bottle: the relative influence of wine back label information on wine choice. Food Qual Prefer. 2010;21(1):22–32. | |

Bruwer J, Saliba AJ, Miller B. Consumer behaviour and sensory preference differences: implications for wine product marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2011;28(1):5–18. | |

2011 Census QuickStats [webpage on the Internet]. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) [updated March 28, 2013]. Available from: http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/0. Accessed November 21, 2011. | |

Lattey KA, Bramley BR, Francis IL. Consumer acceptability, sensory properties and expert quality judgements of Australian Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz wines. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2010;16(1):189–202. | |

Worsley A, Thomson L, Wang WC. Australian consumers’ views of fruit and vegetable policy options. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(4):397–407. | |

Gawel R. The use of language by trained and untrained experienced wine tasters. J Sens Stud. 1997;12(4):267–284. | |

Ballester J, Abdi H, Langlois J, Peyron D, Valentin D. The odor of colors: can wine experts and novices distinguish the odors of white, red and rosé wines? Chemosens Percept. 2009;2(4):203–213. | |

Shaw M, Keeghan P, Hall J. Consumers judge wine by its label. Aust NZ Wine Ind J. 1999;14(1):85–87. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.