Back to Journals » Vascular Health and Risk Management » Volume 10

Sex differences in long-term outcomes of coronary patients treated with drug-eluting stents at a tertiary medical center

Authors Shammas N , Shammas G, Jerin M, Sharis P

Received 23 March 2014

Accepted for publication 28 May 2014

Published 9 September 2014 Volume 2014:10 Pages 563—568

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S64696

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Nicolas W Shammas, Gail A Shammas, Michael Jerin, Peter Sharis

Midwest Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Davenport, IA, USA

Background: Limited data exist on contemporary sex-related differences in long-term outcomes of coronary patients receiving drug-eluting stents. In this study we evaluate differences for males (M) and females (F) in 2-year target lesion failure (TLF) in an unselected consecutive series of patients treated with everolimus-eluting stents (EES) and paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES) at a tertiary medical center.

Methods: Data on 348 consecutive patients (M 221, F 127) stented with EES and PES were retrospectively analyzed. The primary end point of the study was to compare sex-related outcomes in TLF, defined as the combined end point of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularization (TLR). Secondary end points included TLR, target vessel failure, target vessel revascularization, acute stent thrombosis as defined by the Academic Research Consortium, and cardiac death. The cineangiograms of the first consecutive 162 patients (M 105, F 57) were independently reviewed by a cardiologist blinded to clinical outcome, and SYNTAX scoring was performed. Follow-up was achieved using medical records and/or phone calls and was censored at 2 years. Descriptive analysis was performed on all variables. Univariate analysis compared the M and F cohorts. Multivariate analysis using Cox regression was performed to determine independent predictors of TLF with time, including sex as an independent variable in the model.

Results: M had more prior percutaneous coronary interventions and restenotic lesions and a higher prevalence of smoking. They also had longer length of disease and received more stents than F. F were older and had a higher prevalence of prior stroke. Angiographic complexity was not statistically different between the two groups, as judged by SYNTAX scoring (M 20.8±13.8, F 19.7±13.9, P=0.650). At 2-year follow-up, TLF was 27.4% and 24.8% (P=0.614) with no statistical difference between TLR (23.3% versus [vs] 21.6%), cardiac death (2.8% vs 3.2%), and definite and probable stent thrombosis (2.3% vs 0.0%) in M and F, respectively. Cox regression analysis using backward elimination showed that the number of stents per patient was the only independent predictor of TLF with time (hazard ratio 1.201, 95% confidence interval 1.126–1.280, P=0.001).

Conclusion: In this cohort of patients receiving EES and PES, M and F did not have statistically different outcomes at 2-year follow-up, consistent with recent reports in the current era of percutaneous coronary interventions.

Keywords: coronary stent, drug-eluting stent, outcome, target lesion revascularization, sex, woman, man, stent thrombosis

Introduction

Prior to the era of drug-eluting stents (DES), several reports indicated that female sex is an independent predictor of adverse events after percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).1–3 This difference between males (M) and females (F) in long-term outcomes seem to have diminished recently. Several reports suggest that female sex, after adjusting for various clinical and procedural variables, does not appear to independently predict adverse late outcome after PCI.4–16 To the contrary, other reports have continued to indicate that female sex predicts an increased risk of major adverse events and target lesion revascularization (TLR), even in the era of modern PCIs.17–19

In this report we examine our own data for differences between M and F in target lesion failure (TLF) in an unselected consecutive series of patients treated with everolimus-eluting stents (EES) and paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES) and followed for at least 2 years at our medical center, the Genesis Medical Center, Davenport, IA, USA.

Methods

Unselected consecutive patients treated with the PES Taxus® Liberte® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) (n=159) and the EES Xience V® (or Promus®) (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) (n=189) were retrospectively recruited from a single center from October 2008 to September 2009. An earlier manuscript has been published from this data by our group.20 As we have previously described, “Patients who received mixed stents during the index procedure or bypass graft treatment were excluded. The choice of the drug eluting stent was left to an individual operator.” All patients were treated using a femoral approach. Intravascular ultrasound was not used to verify stent apposition and expansion. The majority of patients received unfractionated heparin (82.5%) and the remaining bivalirudin (17.5%) during PCI. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (eptifibatide and abciximab) was in <5% of patients. Demographics, clinical, procedural, and angiographic variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Angiographic variables (including ejection fraction from left ventriculography) were obtained by an independent blinded review of the angiograms to patients’ clinical variables and outcomes. Treated length included the entire stented segment rather than just lesion length. SYNTAX scoring was conducted on the first 162 patients (M 105, F 57) (46% of patients and consecutively) with statistically near identical results. Therefore, scoring the remaining patients would not likely have altered this conclusion.

| Table 1 Demographic and clinical variables |

| Table 2 Procedural and angiographic variables |

Complete follow up on all patients was achieved at 2 years from index procedure using phone calls, medical records or both. The Institutional Review Board at our medical center approved the protocol. A verbal consent was obtained from patients by a phone call after they have been mailed a letter describing the protocol. A standardized script was used to obtain history from patients. “Patients who died during the follow up period had their death certificates retrieved to verify the cause of death.”20

The primary outcome of the study was differences between M and F in TLF, defined as cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) related to target vessel, and TLR. Differences in secondary outcomes (target vessel revascularization [TVR], target vessel failure, acute stent thrombosis as defined by the Academic Research Consortium,21 nonfatal MI, and cardiac death) were prespecified as secondary end points.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed on all variables. Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables and chi-square testing for dichotomous variables. Univariate analysis compared the demographic, clinical, angiographic, and outcome variables between M and F. TLF survival analysis (Kaplan–Meier) was performed for both subgroups. Cox regression analysis used backward elimination modeling for age, New York Heart Association classification, renal failure, history of prior angioplasty, ejection fraction, smoking history, number of stents per patient, total lesion length treated per patient, and patients with treated aorto-ostial, bifurcating, or restenotic lesions. SPSS version 11 (IBM, Amonk, NY, USA) software was used to conduct the analysis.

Results

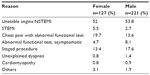

Table 1 illustrates descriptive and clinical variables. M had a higher prevalence of smoking and prior PCIs. F were older and had higher prevalence of prior stroke. Procedural and angiographic variables are shown in Table 2. M had lower ejection fraction, larger coronaries, longer treated lesion length, and more restenotic lesions on presentation and received more stents per patient. Both M and F received an equal proportion of EES and PES. SYNTAX scoring was statistically not different between M and F (M 20.8±13.8, F 19.7±13.9, P=0.650). Unfractionated heparin was the predominant antithrombin used in the laboratory in 82.5% of patients. The rest of the patients received bivalirudin (17.5%), with no statistical difference between M and F (M =37 [16.7%], F =24 [18.9%]). The majority of both M and F were still on dual antiplatelet agents at 1-year follow-up and on aspirin at 2 years. The reasons for the index angiogram are listed in Table 3 and appear not to be different for M and F. The majority of patients were symptomatic with either acute coronary syndromes or chest pain/dyspnea with abnormal functional testing. Less than 20% of patients had no symptoms and were treated for an abnormal functional test or as part of a staged procedure. Despite the complex disease treated, angiographic success, defined as obtaining a residual stenosis of <30%, was achieved in all cases.

| Table 3 Reasons for the index angiogram |

At 2-year follow-up, the primary end point of TLF was 24.8% and 27.4% in both F and M, respectively (P=0.614) (Table 4), with no statistical difference in the secondary end points between target vessel failure (31.5% versus [vs] 35.9%, P=0.414), TLR (21.6% vs 23.3%, P=0.789), cardiac death (3.2% vs 2.8%, P=1.00), definite and probable stent thrombosis (M 2.3% vs F 0.0%), and nonfatal MI (3.2% vs 5.0%, P=0.715). Cox regression analysis using backward elimination showed that the number of stents per patient was the only independent predictor of TLF with time (hazard ratio 1.201, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.126–1.280, P=0.001). TLF was not statistically different between M and F (hazard ratio 0.815, 95% CI 0.460–1.444, P=0.483) (Figure 1).

| Table 4 Two-year primary and secondary outcomes |

| Figure 1 Hazard ratio of target lesion failure (TLF) at 2-year follow-up in males (interrupted line) and females (solid line) who received drug-eluting stents at a tertiary medical center. |

Discussion

Studies prior to the widespread use of DES suggested that F had a higher in-hospital mortality and poorer outcome, late after PCI, than M.1–3 Recent data suggest, however, that long-term clinical outcomes and post-PCI mortality are unlikely to be different between the sexes.1–16 The Rapamycin-eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) studies showed no differences in 3-year outcomes between M and F using rapamycin and paclitaxel DES.5 Solinas et al,10 in a pooled analysis from four randomized trials of sirolimus-eluting versus bare metal stents, analyzed clinical outcomes based on sex. Using multivariate analysis, female sex was not a predictor of clinical outcomes regardless of stent type and despite more comorbidities found in F than in M (older with more frequent presence of diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure). Furthermore, a report from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium PCI registry indicated no difference in mortality between M and F post-PCI.6 Our data are consistent with these reports showing that in multivariate analysis, female sex is not a predictor of TLF at 2-year follow-up, despite older age and higher rate of strokes on presentation.

A higher rate of TLF was seen in both M and F in our study than was reported by several registries or randomized trials.22,23 In SPIRIT IV,21 TLF was 4.2% and 6.8% for EES and PES, respectively. Furthermore, in Second-generation Everolimus-eluting and Paclitaxel-eluting Stents in Real-life Practice (COMPARE),23 the primary composite end point of all-cause mortality, MI, and TVR at 1 year occurred in 6% in EES and 9% in PES. Published data from real-world registries24,25 also showed a low TLR. In the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Second-generation Paclitaxel-eluting Stents Versus Everolimus-eluting Stents in United States Contemporary Practice (REWARDS TLX) multicenter registry,24 the primary composite end point of all-cause death, Q-wave MI, TVR, and stent thrombosis at 1 year was 7.8% for EES and 10.8% for PES. This is in contrast to our data where TLF and TLR were clinically significantly higher than reported in the literature.

The etiology of higher TLF in our data is unclear, but it is likely related to a higher complexity of disease,26 including a larger percentage of bifurcating lesions, ostial disease, and left main disease. Also, the number of stents used, as a reflection of the length of disease treated per patient, is considerably high in both sexes, and more so in M than in F. These lesion subsets correlate with higher TLR and adverse event rates. When adjusting for these complex angiographic variables, sex was not a predictor of TLF. Unadjusted TLF occurred in 32.3% for PES versus 21.5% for EES (P=0.027). However, we have noted no differences in the use of EES versus PES within each sex category (Table 2).

Conclusion

Our data confirm that PCI is safe and effective in women and that differences between the older studies and those that are more recent reside mostly in adjusting for several variables that are independent of the sex category and that correlate with poorer outcomes after PCI. These factors include age (F present to PCI at an older age than M), time to presentation (F tend to recognize fewer heart attack symptoms),27 comorbid factors such as diabetes, and anatomic differences (F have smaller coronary arteries than M, a risk factor for TLR).

One of the limitations of this study is its relatively small size and its retrospective design. An unselected consecutive cohort of patients treated with EES and PES has reduced selection bias. Also, there was no statistical difference on cross-analysis between the choice of the DES and sex category. Another limitation of the study is that the two cohorts are not matched on several variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed, however, to model for these differences and determine the role of sex category as an independent predictor for TLF. Finally, our data are consistent with recently published data on DES showing outcomes were not different statistically between sexes in the current era of post-PCI.

Disclosure

The Midwest Cardiovascular Research Foundation (MCRF) has received research and educational grants from Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. This paper was supported in part by the Nicolas and Gail Research Fund at MCRF and was presented in part, in abstract form at Cardiovascular Research Technologies 2013, Washington DC, USA.

References

Kelsey SF, James M, Holubkov AL, et al. Results of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in women. 1985–1986 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Coronary Angioplasty Registry. Circulation. 1993;87:720–727. | |

Malenka DJ, O’Connor GT, Quinton H, et al. Differences in outcomes between women and men associated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A regional prospective study of 13,061 procedures. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Circulation. 1996;94(Suppl 9):II99–II104. | |

Glaser R, Selzer F, Jacobs AK, et al. Effect of gender on prognosis following percutaneous coronary intervention for stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1446–1450. | |

Narins CR, Ling FS, Fischi M, et al. In-hospital mortality among women undergoing contemporary elective percutaneous coronary intervention: a reexamination of the gender gap. Clin Cardiol. 2006;29:254–258. | |

Onuma Y, Kukreja N, Daemen J, et al; Interventional Cardiologists of Thoraxcenter. Impact of sex on 3-year outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention using bare-metal and drug-eluting stents in previously untreated coronary artery disease: insights from the RESEARCH (Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) and T-SEARCH (Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) Registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:603–610. | |

Duvernoy CS, Smith DE, Manohar P, et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am Heart J. 2010;159:677–683. | |

Tillmanns H, Waas W, Voss R, et al. Gender differences in the outcome of cardiac interventions. Herz. 2005;30:375–389. | |

Ben-Ami T, Gilutz H, Porath A, et al. No gender difference in the clinical management and outcome of unstable angina. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:228–232. | |

Sheiban I, La Spina C, Cavallero E, et al. Sex-related differences in patients undergoing percutaneous unprotected left main stenting. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:795–800. | |

Solinas E, Nikolsky E, Lansky AJ, et al. Gender-specific outcomes after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2111–2116. | |

Presbitero P, Belli G, Zavalloni D, et al. “Gender paradox” in outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention with paclitaxel eluting stents. EuroIntervention. 2008;4:345–350. | |

Thompson CA, Kaplan AV, Friedman BJ, et al. Gender-based differences of percutaneous coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:25–31. | |

Suessenbacher A, Doerler J, Alber H, et al. Gender-related outcome following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: data from the Austrian acute PCI registry. EuroIntervention. 2008;4:271–276. | |

Lansky AJ, Costa RA, Mooney M, et al; TAXUS-IV Investigators. Gender-based outcomes after paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1180–1185. | |

Kovacic JC, Mehran R, Karajgikar R, et al. Female gender and mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: results from a large registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:514–521. | |

Buja P, D’Amico G, Facchin M, et al. Gender-related differences of diabetic patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents: a real-life multicenter experience. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(1):139–143. | |

Ogita M, Miyauchi K, Dohi T, et al. Gender-based outcomes among patients with diabetes mellitus after percutaneous coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. Int Heart J. 2011;52:348–352. | |

Tuomainen PO, Ylitalo A, Niemelä M, et al. Gender-based analysis of the 3-year outcome of bioactive stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an insight from the TITAX-AMI trial. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24:104–108. | |

Niccoli G, Sgueglia GA, Cosentino N, et al. Impact of gender on clinical outcomes after mTOR-inhibitor drug-eluting stent implantation in patients with first manifestation of ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:914–926. | |

Shammas NW, Shammas GA, Sharis P, Jerin M. Age differences in long-term outcomes of coronary patients treated with drug eluting stents at a tertiary medical center. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:471026. | |

US Food and Drug Administration. Circulatory System Devices Panel. Notice of Meeting. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cdrh06.html#circulatory. Accessed June 26, 2014. | |

Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, et al. Everolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1663–1674. | |

Kedhi E, Joesoef KS, McFadden E. Second-generation Everolimus-eluting and Paclitaxel-eluting Stents in Real-life Practice (COMPARE): a randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9710):201–209. | |

Waksman R, Ghali M, Goodroe R, et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Second-generation Paclitaxel-eluting Stents Versus Everolimus-eluting Stents in United States Contemporary Practice (REWARDS TLX trial). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(8):1119–1124. | |

Mahmoudi M, Delhaye C, Wakabayashi K, et al. Outcomes after unrestricted use of everolimus-eluting stent compared to paclitaxel- and sirolimus-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1757–1762. | |

Brodie BR, Stuckey T, Downey W, et al; STENT (Strategic Transcatheter Evaluation of New Therapies) Group. Outcomes and complications with off-label use of drug-eluting stents: results from the STENT (Strategic Transcatheter Evaluation of New Therapies) Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:405–414. | |

Flink LE, Sciacca RR, Bier ML, et al. Women at risk for cardiovascular disease lack knowledge of heart attack symptoms. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:133–138. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.