Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 15

Proportion of Attrition and Associated Factors Among Children Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Public Health Facilities, Southern Ethiopia

Authors Guyo TG , Toma TM , Haftu D , Kote M , Merid F , Kulayta K, Makisha M , Temesgen K

Received 20 May 2023

Accepted for publication 11 August 2023

Published 15 August 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 491—502

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S422173

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Olubunmi Akindele Ogunrin

Video abstract presented by Tamirat Gezahegn Guyo.

Views: 63

Tamirat Gezahegn Guyo,1,* Temesgen Mohammed Toma,1,* Desta Haftu,2 Mesfin Kote,2 Fasika Merid,1 Kebede Kulayta,3 Markos Makisha,4 Kidus Temesgen2

1Department of Public Health, Arba Minch College of Health Sciences, Arba Minch, Ethiopia; 2School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia; 3Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Arba Minch College of Health Sciences, Arba Minch, Ethiopia; 4Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Tamirat Gezahegn Guyo, Department of Public Health, Arba Minch College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 155, Arba Minch, Ethiopia, Tel +251 932573808, Fax +251 468811147, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a major global public health concern. Despite the improved access and utilization of antiretroviral therapy (ART), attrition from care among children continues to be a major obstacle to the effectiveness of ART programs. Hence, this study aimed to assess the proportion of attrition and associated factors among children receiving ART in public health facilities of Gamo and South Omo Zones, Southern Ethiopia.

Patients and Methods: A retrospective follow-up study was conducted in public health facilities of Gamo and South Omo Zones in Southern Ethiopia from April 12, 2022, to May 10, 2022. The proportion of attrition was determined by dividing the number of attrition by the total number of participants. Descriptive statistics were calculated. A binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with attrition. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

Results: The median age of the participants was 5.5 (IQR: 2– 9) years. The proportion of attrition from ART care was 32.4% (95% confidence interval (CI): 27.57% to 37.69%). Death of either of the parents (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.19; 95% CI:1.14, 4.18), or both parents (AOR = 3.19; 95% CI: 1.20, 8.52), hemoglobin level < 10mg/dL (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.21, 4.70), a cluster of differentiation (CD)4 count ≤ 200 cells/mm3 (AOR = 6.78, 95% CI: 3.16, 14.53), CD4 count 200– 350 cells/mm3 (AOR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.16, 6.03), suboptimal adherence (AOR = 6.38; 95% CI: 3.36, 12.19), and unchanged initial regimen (AOR = 6.88; 95% CI: 3.58, 13.19) were factors associated with attrition.

Conclusion: Attrition from care is identified to be a substantial public health problem. Therefore, designing interventions to improve the timely tracing of missed follow-up schedules and adherence support is needed, especially for children with either/both parents died, unchanged initial regimen, low CD4, and/or low hemoglobin level.

Keywords: proportion, antiretroviral therapy, attrition, children, Ethiopia

Introduction

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is attributable to the loss of approximately 40.1 million lives to now.1 By 2020, approximately 1.7 million people under 15 years of age are living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) worldwide.2 In the same year, approximately 99,000 children were lost because of AIDS-related mortality.3

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most affected by HIV, with 90% of adolescents and children living with the virus. 4 By 2020, 460,000 AIDS-related deaths had occurred in the region, predominantly in Southern and Eastern Africa, as indicated by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).2 Ethiopia has 620,000 people living with HIV, 7% of whom are under fifteen years old, with AIDS-related deaths estimated at 2000 per year.5

Attrition is an interruption in the continuum of HIV care, and it includes clients who lost follow-up, died, or stopped care.6,7 It is a central indicator for identifying progress towards achieving the 95 targets of the antiretroviral therapy program.7 Discontinuation of HIV care and support after ART initiation is alarming in resource-limited settings, where the majority of children living with HIV get lost or die.8,9 Globally, 5–29% of children with HIV experience loss to follow-up from HIV care or death within one year of ART initiation.10 The prevalence of attrition among HIV-infected children living with HIV is expected to be high. Attrition among children receiving ART in low-income and middle-income countries is high, ranging from 19% to 23%.8 The magnitude of attrition was determined to range from 14% to 22%, as revealed by studies done in Asia.6,11 Studies conducted in Sub-Saharan African countries showed that approximately 10% to 49.4% of children on ART were attrition from HIV care.12,13 Likewise, studies conducted in Ethiopia indicated that approximately 8–36% of under-fifteen-year-old children experienced attrition from HIV care.14–16

Interruption of HIV care leads to increased morbidity and mortality, increased expenditure on care, and onward transmission.17 It can also weaken clinical outcomes, such as the ongoing provision of opportunistic infection prophylaxis, assessment of functional status and developmental milestones, and timely identification of treatment failure.18 Furthermore, because of this effect of care interruption, only 40% of children living with HIV under the age of 15 were virally suppressed compared with the expected 90% target, globally.3

The factors associated with children’s attrition from HIV care include disclosure-related issues, stigma, the younger age of the children, financial constraints, distance from the care-providing health facility, long waiting times at the health facility, a low hemoglobin level, and a low CD4 count.6,11,17,19,20

Ethiopia has implemented measures to reduce ART attrition among HIV-infected children living with HIV. These interventions include decentralization, free ART treatment, awareness creation, counseling, and phone calls and messages.21,22 Despite these interventions, care interruption is still growing and continues to be a considerable impediment to the effectiveness of ART programs. Hence, assessing attrition and its associated factors is essential to designing effective retention strategies.23

There is limited evidence regarding attrition from care among children receiving ART in Ethiopia, and no evidence in the study setting. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the proportion of attrition and its associated factors in children receiving ART.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Period

An institution-based retrospective follow-up study based on chart review was conducted in public health facilities in the Gamo and South Omo Zones of Southern Ethiopia from April 12, 2022, to May 10, 2022. The town of Arba Minch is 505 Kilometers (KM) southwest of the capital city of Addis Ababa. Jinka Town is approximately 563 kilometers from Addis Ababa and 399 kilometers from Hawassa. In these two Zones, approximately 23 health facilities (two generic hospitals, five Primary Hospitals, and 16 Health Centers) are currently providing pediatric ART services. There were 256 children living with HIV during active ART follow-up in the two Zones. The follow-up schedule was based on the Ethiopian national ART guideline of Ethiopia.17

Population

All children (<15 years) living with HIV who had started ART and registered for care in the public health facilities of Gamo and South Omo Zones were the source population. All children (<15 years) living with HIV who had started ART and registered for care in the selected public health facilities from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021, and who fulfilled the eligibility criteria were the study population.

Inclusion Criteria

All children (<15 years old) living with HIV who were on ART and had at least one follow-up visit from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021, were included.

Exclusion Criteria

Children living with HIV whose charts were missing during the data collection period, those with incomplete data, and those with no follow-up after ART initiation were excluded from the study. Accordingly, 19 charts (8 due to missing client’s chart during data collection, 6 due to incomplete data, and 5 with no follow-up after ART initiation) were excluded from the study.

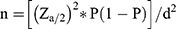

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula [ ] by considering a 95% confidence interval with a confidence level of Za/2 = 1.96, the proportion of attrition (P) of 30.5% taken from a study done in Northwest Ethiopia,16 and 5% margin of error (d). The previous study was selected for sample size calculation due to the similarity of the study topic, it’s being a recent study, and the fact that it was done in a similar setup (country) as the current study. By using the above assumption and adding 5% for incomplete data, the final sample size used in this study was 343.

] by considering a 95% confidence interval with a confidence level of Za/2 = 1.96, the proportion of attrition (P) of 30.5% taken from a study done in Northwest Ethiopia,16 and 5% margin of error (d). The previous study was selected for sample size calculation due to the similarity of the study topic, it’s being a recent study, and the fact that it was done in a similar setup (country) as the current study. By using the above assumption and adding 5% for incomplete data, the final sample size used in this study was 343.

Sampling Technique and Procedure

The public health facilities in the Gamo and South Omo Zones were stratified based on their type of health facility: General Hospitals, Primary Hospitals, and Health Centers. Two primary hospitals and five health centers were selected using a lottery method. Both General Hospitals were included in this study. Children aged <15 years were identified in each of the selected public health facilities using medical record numbers (MRN) obtained from ART electronic databases. By doing this, a total of 349 children (age <15 years) on ART were identified within the time period from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021, in the health facilities. Finally, all 349 patient charts were reviewed, and 330 patient charts that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were included in the study (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 A flow chart of recruitment among children receiving ART in Gamo and South Omo Zones public health facilities, Southern Ethiopia, 2022. |

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

Data were collected using a data extraction checklist developed in English from the standardized ART intake and follow-up forms from national HIV guidelines,17 and by reviewing the related literature.6,11–16,20,24,25 The checklist contained sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-related characteristics of the participants. Data were collected by reviewing the registration books and patient follow-up charts by 14 data collectors and were supervised by three supervisors.

Study Variables

The dependent variable was attrition from care, and independent variables included socio-demographic variables (sex, age, parent status, caregiver-child relationship, the entry point of care, educational status of caregiver, occupation of caregiver, and residence); Clinical variables (nutritional status, developmental milestone, Hemoglobin level, WHO (World Health Organization) clinical staging, CD4 cell count, presence of opportunistic infection (OI), disclosure status, and functional status); and treatment-related variables (ART initiation time after HIV diagnosis, Cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT), ART adherence, type of ART regimen, drug side effects, and regimen change).

Operational Definitions

- Attrition: Children on ART who were lost to follow-up or died within the follow-up time.14,15,24

- Loss to follow-up: Children who have not come for care for three or more consecutive months (≥90 days) after the last missed appointment and are not registered dead or transferred to other health facilities.14,26

- Mortality: Children registered as “died” at the exit form of patient.16

- CD4 count for severe immunodeficiency: The classification was based on children’s age. For children <5 years CD4 <200 cells/mm3, and CD4 <100 cells/mm3 in children ≥5 years.26

- Adherence: Categorized as good: ≥ 95% or ≤3 doses missed monthly; Fair:85–94% or 4–9 doses missed monthly; poor: < 85% or ≥10 doses missed monthly.17

- Nutritional status was measured by weight, age, and body mass index (BMI) for Age. Categorized as underweight (WFA or BMI for age < z-score) and normal (z-score ≥ −2).17

Data Quality Assurance

Data were collected by experienced health professionals trained in comprehensive HIV care and working on clients’ follow-up care. One-day training was provided to all the data collectors and supervisors on the objective of the study, how to review and extract the needed data from medical records, and how to maintain the confidentiality of the data. The checklist is numbered and coded. To ensure accuracy, completeness, and consistency, the data collection process was monitored daily by reviewing and checking completed checklists. The report of the current study was based on strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

The collected data were entered into Epi-Data version 3.1 and then exported to STATA version 14.0. Exploratory data analysis was performed to check for the presence of potential outliers, normality (by Skewness and Kurtosis tests; only baseline hemoglobin level was normally distributed), and level of missing values (viral load had 40.6% missing values and were excluded from analysis). Z-scores to assess nutritional status were generated using WHO Anthro-Plus software. Descriptive statistics were calculated using mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, frequencies, and percentages. A bivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the association between each independent and dependent variable. Variables with a p-value ≤0.25 in bivariable logistic regression, were candidates for multivariable analysis. A multivariable logistic regression model with a backward likelihood ratio method was used to identify the factors significantly associated with attrition. Multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF) value and the mean VIF = 1.14, indicating no threat of collinearity. The goodness of fit of the model was checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (Prob > X2= 0.3743). The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and corresponding p-values were used to identify statistically significant variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

From a total of 349 children (age <15 years) who were receiving ART from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021, approximately 330 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis with a 96.2% completeness rate of charts. Approximately 19 charts of children who did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Children Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy

The median age of the study participants was 5.5 (IQR: 2–9) years, and 46 (13.94%) children aged ≤3 years experienced attrition from ART care. Among the 157 (47.58%) male children receiving ART, 50 (15.15%) were attractive during follow-up. Forty-seven children (14.24%) who participated in this study had lost both parents, and 138 (41.82%) caregivers were aged 35–44 years. Regarding caregivers’ educational status, 170 (51.52%) did not attend formal education. Of the participants’ caregivers, 114 (34.55%) were daily laborers (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Children Receiving ART at Public Health Facilities of Gamo and South Omo Zones, Southern Ethiopia, 2022 (N=330) |

Clinical and Treatment-Related Characteristics of Children Receiving ART

Of the total participants, more than three-fourths (78.48%) were from hospitals, of which 80 (25.45%) experienced attrition. The median BMI for age z-score for both males and females was −1.195 (IQR −2.45–0.18). Regarding baseline weight for age and height for age z-scores, 33.81% and 32.42% of the children had z-scores of <-2, respectively. Among children aged 5–10 years, more than half (66.02%) had an ambulatory baseline functional status. The mean baseline hemoglobin level was 12.51 mg/dl (±2.44 mg/dl SD). A total of 160 (48.48%) study participants received both CPT and Isoniazid prophylaxis therapy (IPT) to prevent opportunistic infections. Based on the study report, the median baseline CD4 count was 470.5 (IQR 293–783) cells/mm3. Of the participants, 176 (53.33%) initiated a Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine (AZT+3TC+NVP)-containing regimen, and only 21 (6.36%) received a dolutegravir (DTG)-containing regimen. The main reason for changing the regimen was new drug availability in more than half (64.9%) of children. In addition, for 15 (862%), 8 (4.6%), 20 (11.4%), and 18 (10.34%) children, the regimen was changed for treatment failure, drug stock-out, other reasons, and unknown reasons, respectively (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Clinical and Treatment-Related Characteristics of Children Receiving ART at Public Health Facilities of Gamo and South Omo Zones, Southern Ethiopia, 2022 (N=330) |

Proportion of Attrition and Associated Factors

This study found that the proportion of patients with attrition was 32.4% (95% CI: 27.57%, 37.69%). Of the overall proportion of attrition cases, loss to follow-up and death accounted for 58.88% and 41.12%, respectively.

In the bivariate logistic regression analysis, attrition was significantly associated with the age of the child, place of residence, parent status, age of the caregiver, educational status of the caregiver, occupational status of the caregiver, mode of entry into the care, presence of tuberculosis, CPT, IPT, hemoglobin level, CD4 count, WHO clinical stage, adherence to treatment, regimen change, and disclosure at a significance level of <0.25.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, parent status, hemoglobin level, CD4 count, adherence to treatment, and regimen change showed a statistically significant association with attrition (p <0.05). The odds of attrition from ART care were doubled (AOR = 2.19; 95% CI: 1.14, 4.18) among children whose either of their parents died when compared to those whose both parents were alive. Likewise, the odds of attrition were three times (AOR = 3.19; 95% CI: 1.20, 8.52) increased among children who lost both of their parents when compared to those whose both parents were alive. Children receiving ART with a hemoglobin level below 10 mg/dL had a 2.39 time increased odds of attrition from care compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.21, 4.70). The odds of attrition among children receiving ART with a CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3 were more than six-fold higher than that among children with a CD4 count ≥350 cells/mm3 (AOR = 6.78, 95% CI: 3.16, 14.53). The odds of being attrition from care among children with a CD4 count 200–350 cells/mm3 was 2.65 times increased than that of children with a CD4 count ≥350 cells/mm3 (AOR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.16, 6.03). Children with suboptimal treatment adherence had 6.38 time increased odds of being attrition from ART care compared with their counterparts (AOR = 6.38; 95% CI: 3.36, 12.19). The odds of attrition were nearly seven times higher among children whose initial regimen was changed than among those whose initial regimen was not changed (AOR=6.88; 95% CI:3.58, 13.19) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, 32.4% of the children living with HIV had attrition from ART care. Parental status, hemoglobin level, CD4 count, adherence to treatment, and regimen change were found to be statistically significant factors associated with attrition from ART care.

This study revealed that 32.4% of patients had attrition. This finding is lower than that of a study conducted in Nigeria,13 which reported a prevalence of 49.4%. This discrepancy may be due to the large sample size and use of long-term data (17 years).13 Differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants may be another reason. The results of this study are in line with those of studies conducted in Northwest Ethiopia (30.5%)16 and Gedeo, Southern Ethiopia (36.2%).14 This consistency may be due to the similarity in data-recording formats and follow-up charts in Ethiopia’s ART program.27 In addition, this may be due to the similarity in the measurements of LTFU.14,16 In contrast, the findings of this study are higher than those of studies conducted in low and middle-income countries,8 22%; Myanmar Asia,6 14%; Mingalardon in Myanmar,11 9.7%); and Southwest China,25 (18.1%). It is also higher than that reported in studies conducted in Eritrea28 (24.2%), the Oromia region, and Addis Ababa15 (7.9%). This discrepancy may be due to differences in the study population; the study done in Myanmar excluded children aged <18 months6 and dissimilarity in the measurement of attrition, defined as discontinuation of ART or loss to follow-up, as defined by a study in China.25 In addition, the difference may be due to the difference in study settings, the Myanmar study11 included only a specialized hospital, the difference in the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants, and improvements in the current healthcare system than former times.

In this study, the odds of receiving ART care were higher in children whose parents died than in those whose parents were alive. This could be due to the absence of parents’ critical role in providing various types of care to children, such as proper feeding, administration, and supervision of medication, combined with the severe economic and social disruption caused by the death of a child’s parents.29

Children receiving ART with low hemoglobin levels had 2.39 times higher odds of attrition. The findings of this study are in line with those of studies conducted in Asia,6 Bali Indonesia,20 and Ethiopia.14–16 This is likely due to exacerbation of previously existing anemia among children who started zidovudine (AZT)-containing regimen, which can further lead to additional opportunistic infections and subsequent attrition.17 Moreover, it may be due to reduced ART tolerance resulting from decreased absorption and immune defenses.

Children with lower CD4 counts had higher odds of attrition than those with higher CD4 counts. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in resource constraint settings,10 Myanmar Asia,6,11 Sub-Saharan Africa,12 and Ethiopia.14 This may be due to reduced CD4+ cells being associated with prompt HIV copying, advancement of AIDS disease, and increased risk of opportunistic infections and other illnesses. Consequently, this will result in exhaustion and noncompliance with ART follow-up exposure to attrition.

Children with suboptimal treatment adherence had increased odds of being attrition to ART care compared with their counterparts. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Ethiopia.14 This can be explained by the fact that suboptimal treatment adherence can result in a high viral load, prompt poor treatment outcomes, and develop antiretroviral drug resistance. This can further lead to a reduced CD4 count, advancement of AIDS, and a flare-up of OIs, which results in attrition.19 However, children are dependent on their caregivers for timely refilling of ARV medications, to properly take prescribed dosages, and for follow-up visits. Moreover, the reduced awareness of caregivers about the treatment benefits of ARV medications might lead to less concern about the regular follow-up schedule.

The odds of attrition were higher for children whose initial regimen did not change than for those who had changed the regimen. The findings of this study are supported by evidence from a study conducted in Eritrea.28 This may be because the majority of old ART regimens have side effects that enhance the progression of the disease and result in subsequent complications. A zidovudine-based ART regimen is associated with anemia, which has an additional effect on the immune system.30 Furthermore, retention in care can lead to an increased likelihood of regimen changes owing to new drugs and treatment guidelines that may be available at different times.

This study used long-term data to estimate the proportion of attrition among children receiving ART. This was a cross-sectional study and did not show a cause-effect relationship. Viral load was not assessed because of incomplete recordings. Though the study included all eligible children found in the study settings to the study, using a relatively smaller sample might affect the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation of the study was it does not identify and report causes of death and loss to follow-up.

Conclusion

Attrition from care is identified to be a substantial public health problem in the study settings. Death of parents, low hemoglobin levels, low CD4 counts, suboptimal adherence, and unchanged regimens were the identified factors associated with high attrition. To minimize attrition from care, special attention should be paid to the early tracing of children with missed follow-up schedules, those whose parents died, children with poor baseline clinical characteristics (CD4 and hemoglobin level), suboptimal adherence, and those who were taking an old regimen. Further longitudinal studies using larger samples to address the effect of the variables with missing data are highly demanding.

Abbreviations

AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; AIDS, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; ART, Antiretroviral Therapy; ARV, Antiretroviral, AZT, Zidovudine; BMI, Body Mass Index; CD4, Cluster of differentiation 4; CI, Confidence Interval; CPT, Cotrimoxazole preventive therapy; DBS, Dried Blood Spot; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; INSTIs, Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors; IPT, Isoniazid Prophylaxis Therapy; LTFU, Loss to Follow-Up; MRN, Medical Record Number; NNRTI, None Nucleated Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors; OI, Opportunistic Infection; PI, Protease Inhibitor; TB, Tuberculosis; UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; VIF, Variance Inflation Factor; VCT, Voluntary Counseling and Testing; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Before the study began, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, with reference number IRB/123/2022. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Convention on Health Research. An official support letter was received from the School of Public Health at Arba Minch University. After explaining the aim of the study, a letter of cooperation was submitted to administrators of the public health facilities and formal official permission was obtained to obtain full access to ART patients’ history and medical records. As the study was retrospective in nature and required a record review, informed consent was not obtained from each participant. The IRB waived this requirement so that the research could be conducted by record review without contacting patients since the study was retrospective (performed by record review). To ensure confidentiality, identifiers (names and unique ART numbers) of the study participants and healthcare providers who examined each study participant were excluded from the data collection tool. After completing data entry, the data were locked with a password, and all filled checklists were locked on a shelf at the end of the study to maintain confidentiality. COVID-19 precautions were ensured throughout the data-collection process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Arba Minch, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Graduate Studies for Ethical Clearance. We also acknowledge the participants, data collectors, and supervisors for their unreserved efforts. The authors would also like to thank hospital administrators and staff for their support.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study did not receive any financial support from funding bodies in public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global situation and trends of HIV; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/hiv-aids.

2. UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2021 fact sheet; 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

3. UNAIDS. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf.

4. UNICEF. Child, HIV and AIDS-regional snapshot-sub-Saharan Africa; 2019. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/south-africa/children-hiv-and-aids-regional-snapshot-sub-saharan-africa-december-2019.

5. UNAIDS. HIV and AIDS estimates country factsheet 2020- Ethiopia; 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/ethiopia.

6. Minn AC, Kyaw NTT, Aung TK, et al. Attrition among HIV positive children enrolled under integrated HIV care program in Myanmar: 12 years cohort analysis. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1510593. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1510593

7. World Health Organization. Consolidated HIV strategic information guidelines: driving impact through programme monitoring and management; 2020.

8. Carlucci JG, Liu Y, Clouse K, Vermund SH. Attrition of HIV-positive children from HIV services in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2019;33(15):2375. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000002366

9. Fox MP, Rosen S. Systematic review of retention of pediatric patients on HIV treatment in low and middle-income countries 2008–2013. AIDS. 2015;29(4):493–502. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000559

10. Abuogi LL, Smith C, McFarland EJ. Retention of HIV-infected children in the first 12 months of anti-retroviral therapy and predictors of attrition in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156506. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156506

11. Kaung Nyunt KK, Han WW, Satyanarayana S, et al. Factors associated with death and loss to follow-up in children on antiretroviral care in Mingalardon Specialist Hospital, Myanmar, 2006–2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195435. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195435

12. Ben‐Farhat J, Schramm B, Nicolay N, et al. Mortality and clinical outcomes in children treated with antiretroviral therapy in four African vertical programmes during the first decade of paediatric HIV care, 2001–2010. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(3):340–350. doi:10.1111/tmi.12830

13. Onubogu CU, Ugochukwu EF. A 17-year experience of attrition from care among HIV-infected children in Nnewi South-East Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06099-3

14. Bimer KB, Sebsibe GT, Desta KW, Zewde A, Sibhat MM. Incidence and predictors of attrition among children attending antiretroviral follow-up in public hospitals, Southern Ethiopia, 2020: a retrospective study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2021;5(1):e001135. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001135

15. Biru M, Hallström I, Lundqvist P, Jerene D. Rates and predictors of attrition among children on antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0189777. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189777

16. Chanie ES, Tesgera Beshah D, Ayele AD. Incidence and predictors of attrition among children on antiretroviral therapy at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019: retrospective follow-up study. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10:20503121221077843. doi:10.1177/20503121221077843

17. Ethiopia FMo HF. National consolidated guidelines for comprehensive HIV prevention. Care and Treatment; 2018.

18. Geng EH, Nash D, Kambugu A, et al. Retention in care among HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: emerging insights and new directions. Curr HIV. 2010;7(4):234–244. doi:10.1007/s11904-010-0061-5

19. World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery, and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery, and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach; 2021:592.

20. Juergens S, Sawitri A, Putra I, Merati P. Predictors of loss to follow up and mortality among children? 12 years receiving anti retroviral therapy during the first year at a referral hospital in Bali: udayana University. Med Arch. 2016;4(2):101–106.

21. Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111421

22. UNAIDS U, and World Health Organization. The incredible journey of the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive; 2016.

23. World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact, and opportunities; 2013.

24. Melaku Z, Lulseged S, Wang C, et al. Outcomes among HIV‐infected children initiating HIV care and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(4):474–484. doi:10.1111/tmi.12834

25. Zeng X, Zhang X, Zhu Q. Treatment outcomes of HIV infected children after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Southwest China: an observational cohort study. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:916740. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.916740

26. World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; 2016.

27. Health EFMo. Guidelines for paediatric HIV/AIDS care and treatment in Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office Addis Ababa; 2008.

28. Mengistu ST, Ghebremeskel GG, Rezene A, et al. Attrition and associated factors among children living with HIV at a tertiary hospital in Eritrea: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2022;6(1):e001414. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001414

29. Vreeman RC, Ayaya SO, Musick BS, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a clinical cohort of HIV-infected children in East Africa. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0191848. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191848

30. Gebremedhin KB, Haye TB. Factors associated with anemia among people living with HIV/AIDS taking ART in Ethiopia. Adv Hematol. 2019;2019:1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/9614205

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.