Back to Journals » Psoriasis: Targets and Therapy » Volume 14

Experiences of Dermatologists and Patients Regarding Psoriasis and Its Connection to Psoriatic Arthritis in Saudi Arabia

Authors Fatani MI , Al-homood I , Bedaiwi M , Al Natour S, Erdogan A, Alsharafi A, Attar SM

Received 16 August 2023

Accepted for publication 19 December 2023

Published 18 January 2024 Volume 2024:14 Pages 11—22

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PTT.S427775

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Uwe Wollina

Mohammad I Fatani,1 Ibrahim Al-homood,2 Mohamed Bedaiwi,3 Sahar Al Natour,4 Alper Erdogan,5 Aya Alsharafi,5 Suzan M Attar6

1Department of Dermatology, Heraa Hospital, Mecca, Makkah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Rheumatology, King Fahad Medical City (KFMC), Riyadh, Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 3Department of Rheumatology, King Saud University, Riyadh, Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Dermatology, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Eastern Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 5Eli Lilly and Company, Riyadh, Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 6Department of Internal Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Makkah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mohammad I Fatani, Department of Dermatology, Heraa Hospital, Al Madinah Al Munawarah Road, Mecca, Makkah, 24227, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated skin disease that has significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, yet it remains challenging for dermatologists to successfully identify and manage. Without effective screening, diagnosis and treatments, psoriasis can potentially progress to psoriatic arthritis. A descriptive, observational cross-sectional study of Saudi Arabian dermatologists and patients with psoriasis was conducted to explore dermatologist and patient perspectives of psoriasis, including diagnosis, management, disease course and unmet needs.

Patients and Methods: This study involved a quantitative questionnaire administered to 31 dermatologists and 90 patients with psoriasis at eight medical centers and was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results: Dermatologists and patients perceived that psoriasis treatment was initiated promptly and that follow-up visits were sufficient. Their perspectives differed in the time to diagnosis and patient reaction, symptom severity, input into treatment goals and educational needs. The dermatologists’ concerns about underdiagnosed psoriasis (13%) were primarily related to patient awareness (87%), physician awareness (58%), and the absence of a regular screening program (52%). Only 31% of patients with psoriasis were highly satisfied with their psoriasis treatment, with 78% experiencing unpleasant symptoms of pain or swelling in joints indicative of psoriatic arthritis. However, only 56% of these patients reported these symptoms to their physicians. When dermatologists were made aware of this difference, referrals to a rheumatologist increased.

Conclusion: The study highlights the importance of strengthening psoriasis management by enhancing dermatologist referral and screening practices, adopting a multidisciplinary approach to care, and improving education and resources for physicians and patients. These results can help to inform the improvement of psoriasis screening, diagnosis and treatment strategies and ensure that expectations meet treatment outcomes. Further research exploring the dermatologist and patient perspectives of the disease pathway from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis and tailor-made treatment approaches is recommended.

Keywords: autoimmune disease, disease pathway, patient satisfaction, provider perspective

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated, polygenic skin disease that affects 125 million people worldwide.1 It is associated with significant morbidity and increased rates of inflammatory arthritis, cardiometabolic diseases and diabetes mellitus.1–4 Currently, psoriasis is treatable but not curable.2

The patient experience of psoriasis is complex and involves a combination of physical and psychological domains that negatively impact their quality of life (QoL).5,6 For more than 50% of patients, this chronic skin condition causes pain, itching, scaling and redness, leading to a diminished capacity to work, sleep disturbances, impaired mobility, irritability, depression, stigma, anxiety and social withdrawal.5 Unfortunately, coping strategies are often maladaptive, and current treatments provide partial but not complete relief. 3,7–11

The management of psoriasis is multifaceted and may be improved by early treatment, dermatology referral, and disease and treatment education, as well as the management of risk factors, comorbidities, and disease progression.12–15 Several studies of physician attitudes to the management of psoriasis have shown that this can be challenging and complicated, with patients with psoriasis requiring more time and support than patients with other conditions.16–19 Furthermore, managing the long-term safety and tolerability of current psoriasis medications can be challenging for physicians and their patients.17,18 There is also a need to determine the most effective treatments, which include pharmacotherapy, topical therapy, phototherapy, systemic non-biologic therapy and systemic biologic therapy, or a combination of these.1,14,20

To better understand the disease pathway of psoriasis, its progression to psoriatic arthritis is worth noting. The slow progression of psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis occurs in one-third of patients with psoriasis.21 Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the joints that often goes undiagnosed because of a lack of screening21 and insufficient patient knowledge.22 The complexity of psoriasis management is further compounded by the need for tailor-made psoriasis treatment programs.9,23,24 Patients with psoriatic arthritis have unique and different treatment goals for psoriasis, and while treatments are usually initiated quickly, satisfaction levels with psoriatic arthritis care remain low.16

The study reported herein was a quantitative questionnaire administered to patients with psoriasis and dermatologists who treat psoriasis in Saudi Arabia. The objectives of this study were to explore the dermatologists’ and patients’ perspectives of psoriasis and understand whether symptoms indicative of psoriatic arthritis were experienced. This included diagnosis, disease management, treatment, referral, priorities, experience, expectations, unmet needs and identification of barriers to and gaps in the optimal management of psoriasis from a dermatologist and patient perspective. A concurrent study exploring the experiences of patients with psoriatic arthritis and rheumatologists was conducted, the results of which have been previously published.16

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a descriptive observational cross-sectional study conducted in Saudi Arabia. Participants included 31 dermatologists, 34 rheumatologists, 90 patients with psoriasis and 98 patients with psoriatic arthritis who consented to participate in the research at eight medical centers. In this paper, we report the results gained from the questionnaires administered to dermatologists and patients with psoriasis. Data collected from rheumatologists and patients with psoriatic arthritis have been published separately.16

In this study, IQVIA, a global provider of clinical research services, was contracted as an independent consultant to coordinate the research. Physicians who routinely treat psoriasis were recruited from a list compiled by IQVIA. Patients were recruited from treating physician offices. To be included, patients had to have an existing diagnosis of psoriasis and be aged ≥18 years; be able to read, speak and understand Arabic or English; and be able and willing to complete the questionnaire. All subjects signed a consent form that outlined the conditions of the research prior to study participation.

Data Source

Data were collected from dermatologists from July to November 2020 and from patients with psoriasis from February to June 2021. The questionnaires were co-designed by clinical experts from Eli Lilly and a steering committee of expert rheumatologists and dermatologists. IQVIA was contracted to recruit participants. IQVIA representatives conducted all face-to-face and telephone interviews and collected and reported data in compliance with ethical principles.

Structured dermatologist interviews included 27 questions completed over 30 minutes (see the Questionnaire for Dermatologists in Supplementary Material 1). Dermatologists answered screening questions on practice location and volume of patients, and survey questions about multidisciplinary approaches, patient volumes, treatments, treatment goal setting and disease management practices. Structured patient interviews included 28 questions completed over 15 minutes (see the Questionnaire for Patients with Psoriasis in Supplementary Material 2). Patients answered demographic screening questions and survey questions on disease course, symptom and disease burden, disease management and disease-related needs and expectations.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted utilizing SPSS version 23; no inferences were made. There were no missing data. Categorical data were presented as percentages of participants; ordinal data were presented as percentage scores for each category and top 2 box (T2B) percentages for ease of comparison. T2B scores combine the proportions of respondents who have selected the two highest possible Likert scale survey responses into a single number.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in Brazil in 2013 and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh (IRB log number 21–192).

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic data from patients who were enrolled at dermatologists’ offices (Table 1) showed that the majority of psoriasis patients in the study held a university degree, and most of them were female. A significant proportion of patients had no history of smoking, and a substantial portion of them worked full-time. Interestingly, none of the patients lived alone, and the average age of participants was approximately 46 years. Many patients had previously received treatment for various comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and thyroid disease, with a quarter of them reporting no comorbid conditions. Notably, these patients demonstrated a good understanding of their condition and could readily recognize common symptoms associated with psoriasis (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Surveyed Participants |

Survey data from dermatologists indicated that more than 80% of their time was spent in public hospitals, with the remaining in privately funded settings (Table 1). At any one time, these dermatologists actively managed 52 cases of psoriasis (range 10–150) and reported a monthly caseload of approximately 370 patients regardless of their condition, of which 35 were being treated for psoriasis.

Perspectives on Psoriasis Referral and Diagnosis

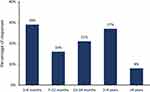

Dermatologists reported concern about the number of patients with psoriasis who are underdiagnosed (13%) and attributed this to a lack of patient awareness (87%), a lack of physician awareness (58%) and the lack of a regular screening program for psoriasis (52%). They reported that most patients with psoriasis (65%) referred to them had a physician contact within 2.5 months and on average had a diagnosis confirmed within 6 months. Half of these dermatologists used a psoriasis screening tool (52%), such as The Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Questionnaire, or Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation. In contrast, almost all (90%) surveyed patients reported that they had their first physician contact within 6 months and, on average, received a psoriasis diagnosis 20 months (range 0–72) after their first psoriasis symptom. However, many were diagnosed within 1–6 months (29%), 7–24 months (37%), or 2–4 years (27%), with the remaining 8% receiving a diagnosis after 4 years (Figure 1). Most patients (70%) stated that their initial visit was with a dermatologist and those who waited to see a dermatologist waited for less than 3 months.

Half of the patients reported accepting their psoriasis diagnosis (52%), with the other half reporting feeling anxious/fearful, shocked or sad (Figure 2a). In contrast, dermatologists perceived that most patients responded with worry/fear (61%) or frustration/depression (19%) when hearing their psoriasis diagnosis (Figure 2b).

Perspectives on Psoriasis Treatment

Psoriasis treatment was initiated on the day of diagnosis in 66% of patients. When patients showed signs of psoriatic arthritis, approximately three-quarters (77%) of dermatologists said they referred patients to a rheumatologist. At the time of referral, 53% of patients were already receiving biologics for suspected psoriatic arthritis. The most common signs and symptoms that prompted these dermatologists to initially refer patients to a rheumatologist included joint swelling/tenderness/inflammation (94%), morning stiffness (81%), enthesitis (58%), asymmetrical joint symptoms (48%), swelling of fingers/toes (45%), back pain (39%), nail changes (26%) and fatigue (13%).

All dermatologists and 80% of patients reported that treatment plans were established. The degree of patient participation in the treatment plan development varied. Patients reported that, in most cases, treatment goals were set solely by the physician (22%) or with some patient input (47%) (Figure 3). Few patients felt that they had the majority of input in their treatment goals, and even fewer believed that they had equal input. Dermatologists reported setting treatment goals for 52% of patients and that <5% of patients set their own goals (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Input on treatment goals from the perspective of patients and dermatologists. In Figure 3, the perspectives of patients and dermatologists regarding treatment goals are presented. It highlights how patients and healthcare professionals may differ in defining and prioritizing treatment objectives. |

Follow-up visits were scheduled routinely, with the majority of patients reporting visits monthly (42%) or every 2–3 months (47%). Most patients were seen for an average of 10–20 minutes (83%) by the dermatologist, with some (6%) needing 20–30 minutes. Similarly, most dermatologists reported that follow-up visits were arranged monthly (45%) or every 2–3 months (48%) and took 10–20 minutes (84%), with some patients requiring 20–30 minutes (13%).

Perspectives on Psoriasis Symptoms and Disease Impact

Patients reported fatigue, itching, sleep disturbance and skin appearance/pain/burning as the most concerning symptoms for them, and dermatologists viewed skin appearance and cracked skin as the top concerns (Figure 4).

To further assess the burden of psoriasis on QoL, the disease’s impact on certain areas of life was rated. For patients, the disease impact was most profound on daily life, social life and family life (T2B: 11%, 10%, 8%, respectively). Similarly, dermatologists perceived the greatest impact to be on social life and intimacy with a partner (T2B: 55%, 45%, respectively).

Perspectives on Psoriasis Education

Many dermatologists reported questioning patients monthly (32%) or every 2–3 months (42%) on non-skin symptoms, and proactively asking questions about morning stiffness (97%), joint pain (94%) and swelling (77%), and swollen fingers/toes (61%). Although most (90%) of the dermatologists educated their patients on disease progression and signs/symptoms of psoriatic arthritis, patients wanted more specific information on treatment convenience (47%), tolerability (26%), safety (19%) and goals/outcomes (19%). In addition, they wanted more discussion on the social impact on life (22%) and family (21%), work-life (18%) and well-being (3%).

Patient and Dermatologist Satisfaction

Patients were mostly satisfied with the management of psoriasis, including the time available to discuss treatments, overall physician interaction, the number of treatment options offered, education/training and level of involvement in decision-making (T2B: 49%, 34%, 32%, 31%, 25%, respectively). Only 31% of patients with psoriasis were highly satisfied with their current treatment. Many patients experienced pain or swelling in joints (78%); however, of these, only 56% informed their physicians, and 22% were referred to a rheumatologist.

Dermatologists indicated that having increased resources and time at their disposal would empower them to better manage various aspects of their patients’ well-being. They believed that additional resources could enhance their ability to address their patients’ emotional state, mitigate the impact of psoriasis on work life, ensure patient compliance and adherence to treatment, address social implications, improve the effectiveness of treatment in controlling disease progression, and ultimately enhance their patients’ overall QoL. Table 2 highlights the similarities and differences in the survey data reported by dermatologists and patients with psoriasis.

|

Table 2 Comparison of the Perspectives of Dermatologists and Patients with Psoriasis on Psoriasis |

Discussion

This study, conducted in Saudi Arabia from 2020 to 2021, explored psoriasis from the perspectives of both dermatologists and patients to seek ways to better understand psoriasis and improve disease management. In addition to this, there was a need to explore whether the symptoms indicative of psoriatic arthritis were being experienced by patients with psoriasis and what actions were being taken by dermatologists to limit disease progression. Findings showed that the perspectives of dermatologists and patients with psoriasis had similarities and differences, with differences including aspects of diagnosis, symptom impacts, patient input into treatment goals and patient educational needs.

Surveyed dermatologists estimated that 13% of patients with psoriasis remained undiagnosed, primarily due to a lack of patient awareness. However, evidence suggests that this may also be a result of the heterogeneous nature of the disease and the challenges in accurately linking the varied skin symptoms specifically to psoriasis10,17,23,25,26 and – in more advanced cases – discerning psoriatic arthritis from other types of arthritis.17,27 Another cause of potential diagnostic delay is misdiagnosis of the pain from psoriatic arthritis-associated enthesitis as fibromyalgia in patients whose psoriatic arthritis manifests mostly as widespread chronic pain.28 Although recommendations on when to refer patients with psoriasis to a rheumatologist are clear,23 referral patterns vary. In this study, 77% of dermatologists stated they referred patients to a rheumatologist at the first sign of psoriatic arthritis. The published evidence suggests lower referral rates. Lebwohl and colleagues18 reported that 6.9% of dermatologists felt the need to refer patients for psoriatic arthritis care or to involve other specialists, and Strand and colleagues29 reported an even lower percentage (6%). Another study noted that 31% of rheumatologists reported delays in psoriatic arthritis referrals.17 Given that only 77% of dermatologists in this survey referred at the first sign of symptoms, and >50% of patients in this study were receiving biologics for suspected psoriatic arthritis at the time of initial rheumatologist referral, a referral delay appears to also be occurring in this population of respondents. It may be that the intent to refer does not translate into actual referrals; further investigation into this issue is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

The authors of this paper previously published the perspectives of rheumatologists and patients with psoriatic arthritis.16 While both dermatologists and rheumatologists acknowledge that these populations are underdiagnosed, patients with psoriasis were diagnosed in approximately one-third of the time taken to achieve diagnosis in patients with psoriatic arthritis (20 months versus 64 months), and those with psoriasis saw a specialist in less than half the time than patients with psoriatic arthritis (2.5 months versus 6 months).16 Although an increasing number of dermatologists do consider patient QoL when deciding on a treatment choice,30 the percentage remains low (28%). Most dermatologists still focus on treating the signs and symptoms of psoriasis.17 In this study, dermatologists prioritized both physical and social factors, with a focus on social life and skin appearance. The majority of study patients (66%) were started on psoriasis treatments by dermatologists; more than half started on the same day of diagnosis with psoriasis. As mentioned, >50% of study participants had already received biologics for psoriatic arthritis. This is similar to the topical therapy utilization (74.9%) and significantly higher than the biological therapy utilization (19.6%) reported by dermatologists in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.17 Such a high proportion of patients receiving biologics and reporting symptoms associated with psoriatic arthritis in this study suggests a substantial number of patient respondents with undeclared or undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis; if this was the case, this could limit the applicability of the results to other psoriasis-only populations.

In this study, dermatologists were the primary guide for treatment goals, with most patients having some or little input. The importance of involving patients in psoriasis decision-making has been well studied.6,27,31 There is a documented need to strengthen communication and shared decision-making between patients with psoriasis and physicians.32

Despite the early treatment initiation in the study population, less than one-third of surveyed patients were highly satisfied with their current treatment plan. The published literature indicates the same. The majority of patients with psoriasis are dissatisfied because their primary goals of therapy were not met with the current treatment.9,17,18,27,31 One study found that only 34% of patients and their dermatologists reported the same level of treatment satisfaction.33 Once progression to psoriatic arthritis occurs, the percentage of highly satisfied patients decreases even further to 22%.16 Some suggest that the ideal treatment goals should be pre-defined by the patient and individualized in a tailor-made treatment program,9 while others suggest a collaborative approach between physicians and patients to reach the goal of minimal disease activity.16 The need to incorporate patients in treatment decision-making is again highlighted here.

The disease burden associated with psoriasis has been linked to reduced QoL, increased comorbidities and increased utilization of healthcare resources.6 These are well documented, but 92% of dermatologists agree that the burden of disease is often underestimated.17 Dermatologists in this study reported that they did not have enough time and resources to better control the impact of psoriasis on patients’ psychological state or work and social life. Similarly, rheumatologists caring for psoriatic arthritis patients felt that they needed more time and resources to better understand how psoriasis impacts patient feelings/well-being.16

The impact of psoriasis on everyday life extends beyond the physical symptoms and significantly impacts the patient’s emotional, family and social life, and their QoL.6,18,27,33 Both dermatologists and patients in this study agreed that family, social and work aspects of life were significantly adversely affected by psoriasis. This aligns with the results of several studies, which confirmed a notable association between psoriasis and psychological comorbidities, including worsening QoL,6 depression, impaired work performance5 and absenteeism.33 For those who progress to psoriatic arthritis, the most profound impact was felt in their social life, and contributed to a decrease in QoL and mental health.16

Unmet education needs were reported in this study. Patients wanted more specific information on treatment convenience, tolerability, goals and safety, as well as additional discussion about the impact of psoriasis on social, family and work life. These results are also reflected in patients with psoriatic arthritis, where research shows that patients wanted more information on treatment convenience, safety, tolerability, impact on work life, family life, and treatment goals/outcomes.16 Increasing patient education has been shown to improve treatment adherence and expectations and to encourage self-care activities.1,30,33,34 Similarly, physicians can benefit from education to improve the accuracy and efficiency of screening, diagnosis and referral18 to reduce psoriasis nontreatment and undertreatment.34

Managing the disease continuum between psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving dermatologists, rheumatologists, other healthcare professionals, and patients and families. The value of close collaboration and joint conferences between dermatologists and rheumatologists has been reported, with benefits including earlier diagnosis and cost savings.35 Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are crucial to control symptoms, prevent joint damage and progression to psoriatic arthritis, and improve overall well-being for individuals affected by these conditions.16

Considerations of patient comorbidities and patient education in psoriasis management are of paramount importance due to the association of psoriasis with various chronic conditions, including chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, mental health, and cardiovascular issues,36,37 as well as smoking.38 Accurate communication and understanding of these comorbidities in terms of absolute risk are essential, as communicating relative risks can lead to unwarranted anxiety and misjudgment of priorities.36 Additionally, smokers with psoriasis tended to require more systemic treatments, emphasizing the adverse effects of smoking on psoriasis severity and management.38 Dermatologists play a vital role by recognizing the elevated occurrence of specific comorbidities in individuals with psoriasis and effectively educating their patients about these associations.37

This study highlights the importance of patient awareness, diagnosis, treatment initiation, and education in managing psoriasis. However, the disease impact and treatment goals differ between psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients, reflecting the distinct nature of each condition.

Limitations of this study include those associated with the study design. Cross-sectional studies have value in determining the association between variables and establishing prevalence but not incidence. This type of study cannot be used to establish a temporal relationship or make causal inferences. Recruitment occurred in the community, which may have encouraged more candid accounts of participants’ experiences. However, the survey sample was small, may not be representative and has the potential for selection bias. Patient respondents were all treated by dermatologists, not rheumatologists, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Data on psoriasis disease severity or the specific treatments that were prescribed, other than biologics, were not collected in this study; the proportion of patients receiving biologics may also suggest a high degree of undeclared or undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, which could have impacted the results. In addition, results focused on one point in time and this precluded analysis of trends. Questions were related to past events, which could be impacted by recall difficulty, and findings have limited generalizability outside of the sampled population, population definition and geographical area.

Conclusion

The results of this comprehensive survey conducted among Saudi Arabian dermatologists treating psoriasis and patients with this condition provide valuable insights into the nuances of psoriasis management. While both medical practitioners and patients concur on the profound impact of psoriasis on social and family life, notable disparities emerge in areas such as patient reactions, diagnostic timelines, symptom significance, patient involvement in goal-setting, and the quality of provided education. These disparities underscore the need for a more holistic approach to psoriasis management, necessitating improvements in dermatologist referral and screening practices, embracing multidisciplinary care models, and enhancing educational resources for both healthcare providers and patients. Furthermore, the vital role of interdisciplinary collaboration with rheumatologists and ongoing communication channels between healthcare professionals and patients is highlighted as a means to align treatment expectations, promoting the timely adoption of effective interventions, including the early incorporation of biologics, to ensure patient-centered, safe, and efficacious strategies for managing psoriasis and averting its progression to psoriatic arthritis.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Clare Koning and Sheridan Henness (Rx Communications, Mold, UK), funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Funding

Funding for this study, manuscript writing, editing, approval, and decision to publish was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure

Alper Erdogan and Aya Alsharafi are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. Mohamed Fatani, Ibrahim Alhomood, Mohamed Bedaiwi, Sahar Al Natour, and Suzan Attar declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

1. Armstrong A, Charlotte R. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatments of psoriasis. JAMA. 2020;323(19):945–960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

2. Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475

3. Georgescu S, Tampa M, Caruntu C, et al. Advances in understanding the immunological pathways in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):739. doi:10.3390/ijms20030739

4. Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Risk factors for the development of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4347.

5. Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(1):91–102. doi:10.1007/s40744-016-0029-z

6. Griffiths CEM, S-J J, Naldi L, et al. A multidimensional assessment of the burden of psoriasis: results from a multinational dermatologist and patient survey. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(1):173–181. doi:10.1111/bjd.16332

7. Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(3):405–423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

8. Ljosaa TM, Bondevik H, Halvorsen JA, Carr E, Wahl AK. The complex experience of psoriasis related skin pain: a qualitative study. Scand J Pain. 2020;20(3):491–498. doi:10.1515/sjpain-2019-0158

9. Kouwenhoven T, van der Ploeg J, van der Kerkhof PCM. Treatment goals in psoriasis from a patient perspective: a qualitative study. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31(1):13–17. doi:10.1080/09546634.2018.1544408

10. Silverthorne C, Lord J, Bowen C, Tillett W, McHugh N, Dures E. Experiences of screening and diagnosis from the perspective of patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PSA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(Suppl.1):1426. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.1024

11. Merola JF, Qureshi A, Husni ME. Underdiagnosed and undertreated psoriasis: nuances of treating psoriasis affecting the scalp, face, intertriginous areas, genitals, hands, feet, and nails. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(3):e12589. doi:10.1111/dth.12589

12. Korman NJ. Management of psoriasis as a systemic disease: what is the evidence?. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):840–848. doi:10.1111/bjd.18245

13. Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: version 2—Advances in psoriatic disease management, COVID-19 vaccines, and COVID-19 treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1254–1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.058

14. Gionfriddo MR, Pulk RA, Sahni DR, et al. ProvenCare-Psoriasis: a disease management model to optimize care. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(3):13030.

15. Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Afach S, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1(4):CD011535.

16. Alhomood I, Fatani M, Bedaiwi M, et al. The psoriatic arthritis experience in Saudi Arabia from the rheumatologist and patient perspectives. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2023;19(4):470–478. doi:10.2174/1573397119666230516162221

17. van der Kerkhof PCM, Reich K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population‐based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(10):2002–2010. doi:10.1111/jdv.13150

18. Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, Van Voorhees AS. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based Multinational Assessment Of Psoriasis And Psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):87–97. doi:10.1007/s40257-015-0169-x

19. Nicolau G, Yogui MM, Vallochi TL, et al. Sources of discrepancy in patient and physician global assessments of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(7):1293–1296.

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psoriasis: assessment and management. Clinical guideline CG153; 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/ifp/chapter/Psoriasis. Accessed

21. Haroon M, Kirby B, Fitzgerald O. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with severe psoriasis with suboptimal performance of screening questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(5):736–740. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201706

22. Renzi C, Di Pietro C, Gisondi P, et al. Insufficient knowledge among psoriasis patients can represent a barrier to participation in decision-making. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(6):528–534. doi:10.2340/00015555-0145

23. Belinchón I, Salgado-Boquete L, López-Ferrer M, et al. Dermatologists’ role in the early diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis: expert recommendations. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111(10):835–846. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.06.004

24. Zheng Y-X, Zheng M. A multidisciplinary team for the diagnosis and management of psoriatic arthritis. Chin Med J. 2021;134(12):1387–1389. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001588

25. Gottlieb A, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis for dermatologists. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31(7):662–679. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1605142

26. Luelmo J, Gratacós J, Moreno Martinez-Losa M, et al. Multidisciplinary psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis unit: report of 4 years’ experience. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(4):371–377. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2013.10.009

27. Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871–881.e1–30. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.018

28. Marchesoni A, De Marco G, Merashli M, et al. The problem in differentiation between psoriatic-related polyenthesitis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology. 2018;57(1):32–40. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex079

29. Strand V, Chin M, Ganguli A, et al. Characterization of psoriatic arthritis [Psa] in a large, integrated health plan: demographics, referral patterns and care management. Arthrit Rheumatol. 2015;67(Suppl 10):673.

30. Moreno-Ramírez D, Fonseca E, Herranz P, Ara M. Treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in clinical practice: a survey of Spanish dermatologists. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101(10):858–865. Spanish. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2010.06.011

31. Polat M, Yalçın B, Allı N. Perspectives of psoriasis patients in Turkey. Dermatologica Sin. 2012;30(1):7–10. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2011.10.001

32. Larsen MH, Hagen KB, Krogstad AL, Wahl AK. Shared decision making in psoriasis: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(1):13–29. doi:10.1007/s40257-018-0390-5

33. Kubanov AA, Bakulev AL, Fitileva TV, et al. Disease burden and treatment patterns of psoriasis in Russia: a real-world patient and dermatologist survey. Dermatol Ther. 2018;8(4):581–592. doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0262-1

34. Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the national psoriasis foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1180–1185. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5264

35. Hein G. Management of dermato-rheumatic syndromes. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(4):463. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/37.4.463

36. Saleem MD, Feldman SR. Comorbidities in patients with psoriasis: the role of the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):191–192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.057

37. Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DM, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1073–1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

38. Temiz SA, Özer İ, Ataseven A, Dursun R, Uyar M. The effect of smoking on the psoriasis: is it related to nail involvement?. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e13960. doi:10.1111/dth.13960

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.