Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

Cross Culture Examination of Perceived Overqualification, Psychological Well-Being and Job Search: The Moderating Role of Proactive Behavior

Authors Abdalla AA, Saeed I, Khan J

Received 4 November 2023

Accepted for publication 16 December 2023

Published 14 February 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 553—566

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S441168

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Alaa Amin Abdalla,1 Imran Saeed,2 Jawad Khan3

1Academic Programs for Military Colleges, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 2IBMS, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan; 3College of Management, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Imran Saeed, Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study delves into the intricate interplay between perceived overqualification, job search behavior, psychological well-being, and proactive behavior, within two distinct and diverse work settings.

Methods: Drawing upon the Person-Job Fit theory, we investigated these dynamics in two unique samples: Sample 1 encompassed corporate sector employees in the United Arab Emirates (N=409), while Sample 2 comprised IT sector workers in Pakistan (N=337). Hayes PROCESS macro were used to examine the proposed hypotheses and AMOS (Version 28) were conducted to examine model fitness.

Results: In Study 1, we established a positive association between perceived overqualification and job search behavior among employees in the UAE corporate sector. Notably, this relationship was mediated by psychological well-being, suggesting that the impact of perceived overqualification on job search behavior is, in part, channeled through its effects on individuals’ psychological well-being. Study 2 showed that proactive behavior exhibited a moderating effect on the negative link between perceived overqualification and psychological well-being. Specifically, employees displaying higher levels of proactive behavior demonstrated a less adverse influence of perceived overqualification on psychological well-being. Importantly, this adaptive effect of proactive behavior was found to indirectly influence job search behavior.

Discussion: The findings highlight the nature of perceived overqualification in the workplace and its varying impact on employee behavior and well-being across different cultural and work settings. The mediation by psychological well-being and moderation by proactive behavior in these relationships underscores the importance of individual responses to perceived job fit issues. These insights are crucial for understanding employee behavior in diverse work environments and can inform practices for managing perceived overqualification.

Keywords: perceived overqualification, psychological well-being, job search behavior, proactive behavior, P-J fit theory

Introduction

Employee overqualification refers to a scenario in the workforce where an employee possesses qualifications like skills, education, and experience that surpass the requirements set for a particular job.1 This mismatch between an employee’s credentials and the demands of the job has become more prevalent globally.2 For instance, approximately 43% of college graduates in the United States were employed in positions that did not necessitate their obtained degrees.3 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) statistics reveal even higher instances of this phenomenon in developing economies like Cyprus, Peru, Romania, and Turkey (OECD, 2019). As an illustration, in Turkey, around 29% of the workforce is believed to be overqualified for their current positions, and an additional 36% are engaged in jobs that significantly differ from their formal educational backgrounds. This situation can result in a person-job misfit, as individuals may have to settle for jobs that they perceive as beneath their skills or expectations due to limited opportunities.4

In recent years, the field of management research has increasingly focused on the concept of perceived overqualification (POQ) and its impact on employee attitudes and behaviors.5 Numerous studies have been conducted, revealing that the feeling of being overqualified for a job has significant implications for employees. These studies have demonstrated that perceiving oneself as overqualified is associated with negative outcomes, including negative job attitudes,6 reduced well-being,7 heightened career stress,8 and a higher likelihood of leaving one’s current job.1 However, a noteworthy trend has emerged in the previous research, indicating that overqualified individuals might actually have positive effects on organizations when certain conditions are met. Despite this potential value that overqualified employees could bring to an organization, the prevailing understanding is that their effectiveness and career prospects often overlooked. Going beyond the simple dichotomy of positive and negative outcomes linked to overqualification, researchers have shifted their focus towards understanding how perceived overqualification influences employees’ career trajectories.8–10 Align with person job fit theory,11 this study will examine how perceived overqualification impacts job searching behavior. The study will delve into the effects of POQ on job search behavior, seeking to understand whether individuals who perceive themselves as overqualified for their current positions are more inclined to actively seek out alternative job opportunities that better align with their qualifications and abilities. This investigation is rooted in the idea that when individuals feel that their current job does not utilize their full potential, they may be motivated to explore roles that offer a better fit for their skill set and aspirations.

The current research endeavors to bridge existing gaps in the literature by exploring a fresh avenue, the role of: psychological well-being as a mediator in the relationship between perceived overqualification and employee job search behavior. Psychological well-being encompasses an individual’s emotional state, life satisfaction, and sense of purpose.12 According to P-J fit theory,13 it is plausible that employees who perceive themselves as overqualified experience lower psychological well-being due to the misalignment between their qualifications and job roles. This reduced well-being might serve as a psychological catalyst for initiating job search behaviors. We argue when individuals experience perceived overqualification, resulting in a decline in their psychological well-being within the workplace, they are likely to exhibit an increased tendency to engage in job searching activities. In other words, as the feeling of being overqualified negatively impacts an employee’s mental and emotional state, they are more inclined to actively seek out alternative job opportunities.

Consequently, we introduce proactive behavior – a type of behavior where individuals take initiative and engage in actions that anticipate and shape future events or outcomes, as a moderator. According to person job fit theory, overqualified individuals may experience feelings of frustration or underutilization due to the mismatch between their qualifications and job responsibilities. However, we argue by engaging in proactive behavior, such as taking on additional responsibilities, suggesting improvements, or seeking skill-enhancing projects, they can enhance their psychological well-being.14 Taking a proactive approach can empower overqualified individuals to improve their psychological well-being and optimize their job search efforts in alignment with their qualifications and desired job roles. By adopting a proactive mindset, individuals can actively address the challenges posed by perceived overqualification and work towards creating a more fulfilling and satisfying career trajectory.15 Our proposed moderated mediation model is depicted in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework. |

This study makes several notable contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it delves into the association between the POQ, and job search behavior provides insights into the behavioral responses of individuals who experience perceived overqualification. It highlights that the experience of being overqualified goes beyond mere dissatisfaction; it prompts proactive efforts to find more suitable job roles. This expanded understanding contributes to a more nuanced comprehension of how employees navigate their careers in response to this specific form of job-role mismatch. Second, the inclusion of psychological well-being as a mediator adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the perceived overqualification-job search relationship. It explains the “why” and “how” behind this relationship. By recognizing that individuals who feel overqualified are more likely to engage in job search activities because their psychological well-being is affected. Third, the identification of proactive behavior as a moderator, contributes to the advancement of theoretical frameworks by integrating the concept of proactive behavior into the perceived overqualification context. It showcases how individual traits interact with perceived overqualification to influence psychological well-being and indirectly job search behavior. This expanded perspective enriches existing theories by accounting for the complexity of employee responses.

Theoretical Overview and Hypotheses Development

Perceived Overqualification and Job Search

Overqualified individuals possess skills, education, and potential that exceed the demands of their current job, they can experience a lack of challenge and fulfillment.2 In alignment with the person-job fit theory, the active job search behavior of overqualified individuals is a direct response to their pursuit of roles that are more in tune with their skills, qualifications, and aspirations.10 The core idea of person-job fit theory is that individuals are more satisfied and perform better when there is a high degree of compatibility between their personal attributes – such as skills, knowledge, and abilities – and the demands of the job.16 By targeting positions that are a better fit, overqualified employees aim to find roles that not only challenge them but also fully utilize their expertise.17 This pursuit is not just about job satisfaction, but also about personal and professional growth. Engaging in work that matches their skill level allows these individuals to apply their knowledge effectively, thus providing a sense of accomplishment and purpose.18 Seeking roles that align with their capabilities not only enhances their engagement and job satisfaction but also opens up prospects for advancement within the organization.4 Such opportunities allow them to contribute meaningfully, experience a sense of accomplishment, and pave the way for career progression.19 Perceived overqualification can drive individuals to look for positions that provide a more stimulating and engaging work environment. Individuals with advanced qualifications and skills often have aspirations for continuous career growth and development.20 When they perceive that their current job does not provide adequate opportunities for advancement, they are more inclined to actively search for positions that offer better prospects.21 Having honed their expertise and knowledge, these individuals seek roles that align with their capabilities and challenge them further. If their current job fails to provide avenues for growth, they may feel stagnant and unfulfilled. The desire for career progression drives them to explore opportunities where they can contribute at a higher level, learn new skills, and take on increased responsibilities.9

When individuals possess talents and qualifications that go unrecognized or unused, they might feel unappreciated and undervalued. This can lead to a sense of frustration and even self-doubt, as they begin to question the worth of their skills and the impact they can make.17 Over time, this can result in decreased self-confidence and a diminished sense of personal value. To address this, individuals might actively seek out roles where their skills are acknowledged and utilized to their fullest potential. Finding a job that aligns with their capabilities not only improves their self-esteem but also reignites their passion for work and their overall sense of purpose. Being valued for their skills and contributions fosters a more positive self-perception and a stronger sense of professional identity.22

H1. POQ is positively related to job search

Psychological Well-Being as a Mediator

According to person-job fit theory, when individuals feel that their skills are underutilized in their current roles, it can lead to a range of negative emotions, such as frustration, boredom, and a sense of being undervalued. This, in turn, can significantly impact their psychological well-being.7 Feeling unrecognized or undervalued for one’s skills can significantly impact an individual’s emotional and psychological well-being. This sense of not being appreciated or valued can stem from various environments, such as the workplace, personal relationships, or within community groups.2 When an individual feels that their skills and contributions are not acknowledged, it can lead to a decrease in self-esteem. They may start doubting their abilities and worth, which can lead to a negative self-perception. This lowered self-esteem can impact various aspects of life, including decision-making, relationships, and openness to new opportunities. As a result of the above factors, individuals may experience psychological distress, including feelings of anxiety, dissatisfaction, and overall negative emotions. This distress can have broader impacts on their mental health and well-being.23 When individuals are unable to fully apply their skills and expertise, their sense of competence and self-esteem may suffer. This can further contribute to a negative cycle of dissatisfaction and diminished well-being.24

As individuals experience job dissatisfaction due to underutilization, their psychological well-being may decline. Their self-esteem, sense of competence, and overall happiness can be negatively affected. This diminished psychological well-being then acts as a driving force for seeking out new opportunities.7 Overqualified individuals may actively look for roles that better align with their skills, aspirations, and values in an attempt to improve their overall well-being.25 Pursuing roles that provide more challenging tasks, growth opportunities, and a sense of purpose can help them restore their psychological well-being and regain a positive self-perception.6 Psychological well-being also affects the intensity and effectiveness of job search efforts. If an individual’s self-esteem and overall mental health have been negatively impacted by feeling overqualified, they might approach job search with a sense of urgency and determination.9 Those with higher psychological well-being might engage in more strategic and focused job search activities, as they are better equipped to evaluate potential opportunities objectively and make well-informed decisions.26 Overqualified individuals may indeed be more inclined to seek out new opportunities where their skills can be better utilized, leading to improved job satisfaction, engagement, and overall well-being.20

H2. POQ is negatively related to psychological well-being H3. Psychological well-being mediates the link between POQ and job search

Moderating Role of Proactive Behavior

Proactive individuals may actively seek opportunities to enhance their job roles or address the dissonance between their qualifications and job requirements. By doing so, they can mitigate the negative impact of perceived overqualification on their psychological well-being.27 This mismatch between their capabilities and job responsibilities can lead to frustration, dissatisfaction, and a decrease in psychological well-being.24 These negative emotions stem from the perception that their potential is being wasted, and their professional growth is hindered.28 However, we argue when employees engage in proactive behaviors such as seeking additional responsibilities, volunteering for challenging projects, or pursuing skill development opportunities, they can experience a greater sense of control and satisfaction in their roles. This, in turn, can mitigate the adverse effects of perceived overqualification on their psychological well-being.19 Moreover, proactive individuals may find ways to better align their qualifications with their job tasks, making their work more meaningful and satisfying. They are also more likely to take charge of their career development, which can enhance their overall sense of well-being.29 Engaging in proactive behaviors allows overqualified individuals to reshape their roles to better align with their capabilities. This, in turn, can lead to a more positive psychological well-being.30 Proactive employees experience a greater sense of accomplishment, as they are actively contributing to their work environment and making the most of their skills.31 Actively seeking additional tasks or responsibilities within their current job can provide overqualified individuals with a sense of purpose and challenge. This can help counteract feelings of underutilization and boredom, ultimately improving their job satisfaction and psychological well-being.32

H4a. Proactive behavior moderates the negative relationship between POQ and psychological well-being so that the relationship is low when proactive behavior is high compared with when proactive behavior is low.

Integrated Model

In summary, our proposition posits that employees who perceive themselves as overqualified may harbor surplus capabilities but experience a diminished level of psychological well-being, which in turn stimulates job-searching behaviors. However, the influence of POQ on specific employee attitudes and behaviors, mediated by psychological well-being, may be contingent on the degree of proactive behavior exhibited. Elevated levels of proactive behavior can potentially mitigate the connection between overqualification and psychological well-being, thereby maximizing the strength of the indirect effect. Consequently, we hypothesized that the indirect relationships between POQ and job-searching behaviors, mediated by psychological well-being, are subject to moderation by proactive behavior, as articulated in the ensuing hypothesis:

H4b. The indirect effect of POQ on job search, via psychological well-being, is conditional on proactive behavior so that the indirect effect is weak when proactive behavior is high but higher when proactive behavior is low.

Materials and Methods

We conducted two separate studies to investigate our research hypotheses. In Study 1, we examined the association between POQ and job search while also examining the mediating role of psychological well-being. Study 2 had a dual purpose: to replicate the primary findings from Study 1 and to investigate the moderating impact of proactive behavior. We recruited participants from diverse cultural and organizational backgrounds. Specifically, Study 1 involved employees from the corporate sector in the United Arab Emirates, while Study 2 focused on individuals in the IT sector in Pakistan. This broad recruitment approach aimed to ensure that our conclusions regarding the connections between POQ, psychological well-being, proactive behavior and job search were not limited to a specific, narrowly defined context.

Study 1 – Participants and Procedure

Sample 1 encompassed corporate sector employees in the United Arab Emirates (N=409). Participants were from the textile sector (25.23%), service (32.56%), telecommunication (22.45%) and educational (19.76%). The data was collected via an online questionnaire platform. Convenience sampling technique with time lag study was adopted. Informed consent was taken from the participants before sending the questionnaire and affirming that their participation in the study will be confidential and the collected data will be used for research purposes only and has been confirmed that they actually overqualified. In the current research, we collect data at time 1 regarding demographic variables and perceived overqualification, at time 2, we collected data regarding psychological well-being and at time 3, we collected data regarding job search to reduce common method bias.33 It was communicated that all the participants must be over 18 years of age. The ratio of male participants in the study were (63.8%), while female were (32.2%) and the average age of the participants were 36.28 years. According to the respondents’ levels of education, 29.6% had completed high school, 59.7% had earned a bachelor’s degree, and 10.8% had earned a master’s or above.

Measures

Perceived Overqualification

To measure perceived overqualification we used the scale of Maynard, Joseph, Maynard34 with nine-items. Sample item of the scale is “My job requires less education than I have” (α = 0.92).

Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being were measured by using 8 items from the flourishing scale developed by Diener, Napa Scollon, Lucas.35 Sample items includes “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life” and “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities”, (α = 0.89).

Job Search

We used six-item active job search behavior scale to measure employees’ job searching behaviors developed by Blau.36 The scale slightly modified from original scale to reflect current job searching practice. The items includes “Sent out resumes to potential employers”, “Filled out a job application”, “Telephoned a prospective employer”, “Listed yourself as a job applicant on job recruitment websites or in a professional association”, “Contacted an employment agency, executive search firm, or professional employment service”, and “Had a job interview with a prospective employer”. (α = 0.74).

Control Variables

Previous research suggests that age and gender are associated with job search behaviors.37,38 Therefore, our data analyses controlled for age and gender.

Study 1 – Results and Discussion

Preliminary Analysis

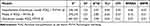

Table 1 presented means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities. Internal consistency across all variables was found to be satisfactory and met acceptable standards. Furthermore, it was observed that all correlations between variables exhibited consistent and expected directional relationships. The scale reliability of variables was in the acceptable range (α > 0.70). The correlation between POQ and psychological well-being is significant and negative (r = −0.334**), POQ and job search (r= 0.205**), followed by psychological well-being and job search (r= −0.564**). Results showed that POQ, psychological well-being, and job search were significantly correlated. These significant correlations among the study variables provided initial support to test the study’s proposed hypotheses.

|

Table 1 Correlations |

Using AMOS, we performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to evaluate the discriminant validity of the variables. Table 2 shows the results of a series of CFA’s. We compared the model fitness of the three-factor model consisting of all rated variables (POQ, psychological well-being and job search) with several other models. Table 2 shows that, compared to all other models that included combining latent variables, the three-factor model provided the best model fit (RMSEA= 0.06, CFI = 0.92, TLI=0.90, SRMR= 0.03).

|

Table 2 Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Study 1 |

Hypotheses Testing

In the statistical evaluation of our hypotheses, we employed the Process macro, a tool that facilitates the concurrent estimation of the direct, mediation, and moderation effects as advocated by Hayes et al (2017). As indicated in the results presented in Table 3, a significant negative association was observed between perceived overqualification (POQ) and psychological well-being (β= −0.192, SE= 0.027, p < 0.001). These findings substantiate the hypothesis that a misalignment between an employee’s qualifications and their job roles detrimentally impacts psychological well-being, thereby providing support for Hypothesis 1. Moreover, the results shows that there is a positive association between POQ and job search (β= 0.109, SE= 0.026, p < 0.001). Overqualified individuals may not feel a strong attachment to their current job due to the perceived lack of fit. This can lead to a higher likelihood of searching external job opportunities, thus supporting hypothesis 2. Table 3 lists the mediation-related findings, obtained from the Process macro’s Model 4. The results shows that psychological well-being mediates the path between POQ and job search (β= −0.127, SE= 0.013, p < 0.001, LL −0.154; UL −0.102), thus supporting hypothesis 3.

|

Table 3 Hypotheses Results for Study 1 |

Discussion

The negative coefficient (β = −0.192***) suggests that there is a significant negative association between POQ and Psychological Well-being. In other words, as POQ increases, psychological well-being tends to decrease. This result aligns with the general understanding that feeling overqualified for a job can lead to dissatisfaction, frustration, and potentially impact overall psychological well-being. The positive coefficient (β = 0.109***) indicates a significant positive association between POQ and Job Search behavior. This means that as POQ increases, individuals are more likely to engage in job search activities. This finding supports the idea discussed earlier that individuals who feel overqualified for their current roles are more likely to actively seek out new job opportunities that better match their qualifications and provide greater challenges. The coefficient (β = −0.127***) suggests that there is a significant negative relationship between POQ and Psychological Well-being, which in turn has a significant negative association with Job Search. This implies that as POQ increases, psychological well-being decreases, which then leads to an increase in job search behavior. This sequence of relationships indicates that feeling overqualified not only directly affects job search but also indirectly through its impact on psychological well-being.

Study 2 – Participants and Procedure

In study 2, we collected data from IT sector workers in Pakistan (N=337). The data was collected via paper pencil. Informed consent was taken from the participants before sending the questionnaire and affirming that their participation in the study will be confidential and the collected data will be used for research purposes only. In the current research, we collect data at time 1 regarding demographic variables and perceived overqualification, at time 2, we collected data regarding proactive behavior and psychological well-being and at time 3, we collected data regarding job searching behavior. It was communicated that all the participants must be over 18 years of age. The ratio of male participants in the study were (62.3%), while female were (37.7%) and the average age of the participants were 34.74 years. According to the respondents’ levels of education, 17.5% had completed high school, 65.3% had earned a bachelor’s degree, and 17.2% had earned a master ‘degree or above.

Measures

POQ (α = 0.72), psychological well-being (α = 0.91), and job searching behavior (a = 0.70) were all measured using the same scales as Study 1. In study 2, we measured proactive behavior by using a six items scale derived from39 proactive behavior scale. A sample item is, “I enjoy facing and overcoming obstacles to my ideas” (α = 0.73). Similar to the approach taken in Study 1, we conducted all hypothesis tests in duplicate, once with the inclusion of control variables and once without, in order to ascertain the stability of the results. This practice reaffirms the robustness of our findings.40

Control Variables

We used the same control variables as in study 1.

Study 2 – Results and discussion

Preliminary Analysis

In Table 4, we provided information on means, standard deviations, correlations, and the reliability of scales. The internal consistency among all variables was deemed satisfactory and met acceptable criteria. Moreover, the correlations between variables consistently demonstrated the expected directional relationships. The scale reliabilities of the variables were within the acceptable range, with all alpha (α) values exceeding 0.70. There was a correlation between the POQ and psychological well-being (r = −0.082*), POQ and job search (r= 0.443**), followed by psychological well-being and job search (r =−.522**). These significant correlations among the study variables provided initial support to test the study’s proposed hypotheses.

|

Table 4 Correlations and Descriptive Statistics |

Using AMOS, we performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to evaluate the discriminant validity of the variables. Table 5 shows the results of a series of CFA’s. We compared the model fitness of the three-factor model consisting of all rated variables (POQ, psychological well-being and job search) with several other models. Table 5 shows that, compared to all other models that included combining latent variables, the four-factor model provided the best model fit for study 2 (RMSEA= 0.06, CFI = 0.91, TLI=0.93, SRMR= 0.03).

|

Table 5 Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Study 2 |

Hypotheses Testing

PROCESS Hayes41 were used to test the proposed hypothesis as examined in study 1, Table 6 results shows that there is a negative relationship between POQ and psychological well-being (β= −0.064, SE= 0.043, p > 0.005), supporting Hypothesis 1. Whereas there is a positive relationship between POQ and job search (β= 0.402, SE= 0.045, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis 2. The mediation results shows that psychological well-being mediates the path significantly between POQ and job search (β= −0.049, SE= 0.021, p < 0.001, LL −0.095; UL-0.009), supporting Hypothesis 3.

|

Table 6 Hypotheses Results for Study 2 |

To gain deeper insights into this interaction, we conducted a detailed analysis by plotting simple slope regression lines of psychological well-being regressed on POQ for both high and low levels of proactive behavior. Specifically, we considered values that were one standard deviation above (+1 SD) and one standard deviation below (−1 SD) the mean of proactive behavior, following the approach outlined by Aiken, West, Reno.42 The study showed that proactive behavior moderates the relationship between POQ and psychological well-being (β = −0.162, 95% CI [−.313; −0.010], p <0.005), such that when proactive behavior was high, the link between POQ and psychological well-being was found to be weak. The results suggests that, when the interaction between “POQ“ and “proactive Behavior” increases by one unit, ”psychological Well-being” is expected to decrease by approximately 0.162 units, all else being constant (see Figure 2); thus hypothesis 4a was accepted. Moreover, the results reveal that POQ is significantly related to job search, albeit indirectly via psychological well-being. The strength of this indirect effect is dependent on proactive behavior. Specifically, when proactive behavior is high, the impact of POQ on job search via psychological well-being is less pronounced (β = 0.0680, SE=0.0354) than when psychological safety is low (β = −0.0773, SE= 0.0305), as shown in Table 7, supporting hypothesis 4b.

|

Table 7 Moderated Mediated Results |

|

Figure 2 Moderating role of Proactive Behavior. |

General discussion

The study’s findings suggest a positive association between POQ and job search behavior among employees in the UAE corporate sector and IT sector of Pakistan. This means that individuals who feel overqualified for their current roles are more likely to engage in active job search behaviors, perhaps seeking positions that better align with their qualifications and capabilities. This aligns with previous research that overqualified individuals may engage in career planning to find more suitable positions that align with their skills and aspirations, increasing their motivation to achieve higher career goals.10 Moreover, the study identifies psychological well-being as a mediator. In other words, the negative impact of POQ on job search behavior is explained by its effect on individuals’ psychological well-being. This implies that when individuals feel overqualified and experience decreased psychological well-being as a result, they are more motivated to search for alternative job opportunities that might provide better job-person fit. Such results are align with Khan et al study, asserted that due to person job misfit leads to job boredom. Ma, Shang, Zhao, Zhong, Chan43 suggested that overqualified employees are prone to experience negative job attitudes and reduced motivation towards their job tasks. This phenomenon can also lead to a decrease in psychological well-being due to the mismatch between the person and the job requirements, commonly referred to as person-job misfit. When individuals perceive a significant misfit between their skills, qualifications, and the demands of their job role, it can result in feelings of frustration, dissatisfaction, and reduced psychological well-being. This misalignment may contribute to increased stress, lower job satisfaction, and overall negative emotional experiences for the overqualified employees.

In study 2, focusing on IT sector workers in Pakistan, the research examines the role of proactive behavior as a moderating factor. The findings suggest that proactive behavior has a buffering effect on the negative association between POQ and psychological well-being. In other words, individuals who exhibit higher levels of proactive behavior are better able to mitigate the adverse impact of feeling overqualified on their psychological well-being.30 This adaptive effect of proactive behavior is further extended to job search behavior. The study indicates that proactive behavior indirectly influences job search behavior by influencing the negative link between POQ and psychological well-being. According to Peng, Yu, Peng, Zhang, Xue,19 being proactive benefits highly skilled individuals by boosting their psychological well-being. This means taking initiative and being proactive can help those who are overqualified for their roles feel better mentally. This suggests that individuals with high proactive behavior not only experience less negative psychological impact from perceived overqualification but are also less driven to engage in job search behaviors as a coping mechanism.44

Theoretical Implications

By establishing a positive link between POQ and job search, this finding validates the concerns expressed in previous research about the potential negative impact of feeling overqualified.45,46 It supports the idea that overqualified individuals are more likely to actively seek person job fit.47 This validation reinforces the importance of addressing perceived overqualification as a genuine concern within the workplace. POQ and job searching behavior relationship provides insights into the behavioral responses of individuals who experience perceived overqualification. It highlights that the experience of being overqualified goes beyond mere dissatisfaction; it prompts proactive efforts to find more suitable job roles. This expanded understanding contributes to a more nuanced comprehension of how employees navigate their careers in response to this specific form of job-role mismatch. The positive association between POQ and job searching behavior contributes to the advancement of existing theories, such as person-environment fit theories. This relationship underscores the importance of aligning an individual’s qualifications and job roles to achieve job satisfaction and career success.48

This study adds to the examination of how psychological factors interact with external job-related factors to shape employee behavior. The inclusion of psychological well-being as a mediator adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the perceived overqualification-job search relationship. It explains the “why” and “how” behind this relationship. By recognizing that individuals who feel overqualified are more likely to engage in job search activities because their psychological well-being is affected. This mediation contributes to the theoretical landscape by linking concepts such as perceived overqualification, psychological well-being, and job search in a coherent framework. It enhances existing theories by highlighting the internal psychological processes that bridge the gap between an employee’s perception of being overqualified and their subsequent proactive job search behaviors.49 This holistic approach allows researchers to better understand the interplay between these factors and their combined influence on an individual’s career decisions. It sheds light on the multifaceted nature of the association, emphasizing the significance of psychological well-being as a pivotal link. In essence, recognizing psychological well-being as a mediator enhances existing theories by providing a more nuanced explanation for the perceived overqualification-job search connection. It underscores the importance of addressing individuals’ internal experiences and emotional responses when studying how perceived overqualification drives job search behaviors. This deeper understanding can inform both research and practical strategies for organizations to create environments that foster employee well-being and encourage proactive career management.50

By incorporating proactive behavior as a moderator, researchers delve deeper into understanding the nuanced relationship between these factors. This addition acknowledges that overqualified individuals possess varying levels of proactivity, which can influence how they respond to the challenges posed by perceived overqualification. Proactive individuals are more likely to take charge of their circumstances and actively seek solutions, such as seeking additional responsibilities or skill development.29 This expanded perspective enriches existing theories by accounting for the complexity of employee responses. It recognizes that the impact of perceived overqualification is not uniform across all individuals. Instead, it is influenced by their individual tendencies to engage in proactive behaviors. This complexity adds depth to our understanding of how perceived overqualification affects psychological well-being and indirectly shapes job search behavior. Furthermore, the identification of proactive behavior as a moderator highlights the importance of individual agency in managing the consequences of POQ. It underscores that employees are not passive recipients of circumstances but active agents who can influence their experiences through their behaviors.49

Practical Implications

Organizations should recognize that employees who perceive themselves as overqualified may experience negative emotions and job dissatisfaction. It’s crucial for managers to engage in open communication with such employees to understand their concerns and explore ways to better align their skills with their roles. This might involve offering stretch assignments, additional responsibilities, or opportunities for skill development. Encouraging proactive behavior within the workforce can be beneficial. Managers should create an environment where employees feel empowered to take initiative, propose new projects, and suggest process improvements. Recognizing and rewarding proactive efforts can motivate employees to actively shape their roles, mitigating the negative effect of POQ. Organizations should prioritize the psychological well-being of their employees. Providing resources for stress management, fostering a positive work environment, and promoting work-life balance can help individuals cope with the emotional strain that might result from perceived overqualification. Offering opportunities for growth and advancement can address the concerns of overqualified employees. Providing avenues for skill development, lateral movement, or vertical progression can keep employees engaged and motivated. Encouraging employees to customize their roles to better suit their skills and interests can enhance job satisfaction and psychological well-being. This can be achieved by allowing employees to adjust certain job tasks or responsibilities to match their abilities and preferences. Organizations can provide training and workshops to enhance employees’ proactive behavior skills. Training sessions focused on communication, leadership, and innovation can equip employees to actively contribute to their roles and the organization’s success. During the hiring process, organizations should strive for a proper match between job requirements and the skills of potential candidates. Ensuring a good fit reduces the likelihood of perceived overqualification issues in the future. Implementing employee assistance programs (EAPs) can offer employees access to resources such as counseling and wellness programs to support their mental and emotional well-being.

Limitations and Future Avenues

While the examination of the associations between POQ, job search behavior, psychological well-being, and proactive behavior provides valuable insights, there are several limitations and potential areas for future research. Different countries have distinct cultural norms, values, and work-related practices. Perceptions of overqualification, psychological well-being, and job search behavior can vary significantly across cultures. It’s important to acknowledge these differences and consider whether the findings can be generalized beyond the specific countries studied. To enhance the validity of findings, future research could include a more extensive cross-cultural comparison involving a diverse range of countries. This could provide insights into how different cultural contexts impact the associations between POQ, psychological well-being, and job search behavior.

Ensuring that the measurement scales used in both countries are equivalent in terms of meaning and interpretation can be challenging. Differences in language, cultural understanding, and response tendencies might affect the validity of the comparisons. Combining quantitative data with qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, can provide a more holistic view of individuals’ experiences of perceived overqualification and its impact on job search behavior and psychological well-being. Investigating how cultural factors, such as collectivism vs individualism or power distance, moderate the relationships among these variables can lead to a deeper understanding of their dynamics in different cultural settings. Further analysis can explore whether the relationships observed are consistent across both countries or if there are differences in the strength or direction of the associations. Understanding these nuances can provide insights into the role of culture in shaping these relationships.

Conclusion

The study delved into the interplay between perceived overqualification, job search behavior, psychological well-being, and proactive behavior across diverse work settings. Drawing upon the Person-Job Fit theory, the research demonstrated a positive link between POQ and job search behavior in the UAE corporate sector, with psychological well-being mediating this relationship. Furthermore, in the context of IT sector workers in Pakistan, the study highlighted the pivotal role of proactive behavior as a moderator, buffering the negative effect of POQ on psychological well-being. This adaptive effect of proactive behavior extended its influence to job search behavior, indicating a nuanced mechanism of coping and adaptation. By juxtaposing two culturally distinct samples, this study expands our understanding of these dynamics and contributes valuable insights into the complex dynamics shaping individuals’ responses to perceived overqualification in their pursuit of meaningful and fulfilling work experiences.

Data Sharing Statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Statement

The procedures carried out in the studies involving human participants were approved by Academic Programs for Military Colleges, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi and IBMS, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan research review board. These procedures were in full compliance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent revisions, or equivalent ethical principles that govern the ethical treatment of human subjects in research.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study.

Funding

The research is funded by an internal grant from cost center 19300756 at Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bochoridou A, Gkorezis P. Perceived overqualification, work-related boredom, and intention to leave: examining the moderating role of high-performance work systems. Personnel Rev. 2023. doi:10.1108/PR-07-2022-0474

2. Allan BA, Sterling HM, Kim T, Joy EE, Kahng DS. Perceived overqualification among therapists: an experimental study. J Career Assess. 2023;2023:10690727231185173.

3. Rose SJ. How many workers with a bachelor’s degree are overqualified for their jobs? Urban Institute. 2017;1:1–33.

4. Khan J, Saeed I, Fayaz M, Zada M, Jan D. Perceived overqualification? Examining its nexus with cyberloafing and knowledge hiding behaviour: harmonious passion as a moderator. J Knowledge Manage. 2022;27(2):460–484. doi:10.1108/JKM-09-2021-0700

5. Tomás I, González-Romá V, Valls V, Hernández A. Perceived overqualification and work engagement: the moderating role of organizational size. Curr Psychol. 2022;2022:1–11.

6. Erdogan B, Bauer TN. Overqualification at work: a review and synthesis of the literature. Ann Rev Org Psychol Org Behavior. 2021;8(1):259–283. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-055831

7. Wassermann M, Hoppe A. Perceived overqualification and psychological well-being among immigrants. J Personnel Psychol. 2019;18(1):34–45. doi:10.1027/1866-5888/a000219

8. Ma C, Ganegoda DB, Chen ZX, Jiang X, Dong C. Effects of perceived overqualification on career distress and career planning: mediating role of career identity and moderating role of leader humility. Human Resour Manage. 2020;59(6):521–536. doi:10.1002/hrm.22009

9. Erdogan B, Karakitapoğlu‐Aygün Z, Caughlin DE, Bauer TN, Gumusluoglu L. Employee overqualification and manager job insecurity: implications for employee career outcomes. Human Resour Manage. 2020;59(6):555–567. doi:10.1002/hrm.22012

10. Khan J, Saeed I, Zada M, Nisar HG, Ali A, Zada S. The positive side of overqualification: examining perceived overqualification linkage with knowledge sharing and career planning. J Knowledge Manage. 2023;27(4):993–1015. doi:10.1108/JKM-02-2022-0111

11. Cable DM, Parsons CK. Socialization tactics and person‐organization fit. Personnel Psychol. 2001;54(1):1–23. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00083.x

12. Frost S, Kannis-Dymand L, Schaffer V, et al. Virtual immersion in nature and psychological well-being: a systematic literature review. J Environ Psychol. 2022;80:101765. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101765

13. C-q L, H-j W, J-j L, Du D-Y, Bakker AB. Does work engagement increase person–job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. J Vocational Behav. 2014;84(2):142–152. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.12.004

14. Tsai H-Y. Do you feel like being proactive day? How daily cyberloafing influences creativity and proactive behavior: the moderating roles of work environment. Computers in Human Behavior. 2023;138:107470. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107470

15. Matsuo M. The role of work authenticity in linking strengths use to career satisfaction and proactive behavior: a two-wave study. Career Dev Int. 2020;25(6):617–630. doi:10.1108/CDI-01-2020-0015

16. Wu IH, Chi NW. The journey to leave: understanding the roles of perceived ease of movement, proactive personality, and person–organization fit in overqualified employees’ job searching process. J Organizational Behav. 2020;41(9):851–870. doi:10.1002/job.2470

17. Khan J, Ali A, Saeed I, Vega-Muñoz A, Contreras-Barraza N. Person–job misfit: perceived overqualification and counterproductive work behavior. Front Psychol. 2022;13:936900. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.936900

18. Kengatharan N. Too many big fish in a small pond? The nexus of overqualification, job satisfaction, job search behaviour and leader–member exchange. Manage Res Practice. 2020;12(3):33–44.

19. Peng X, Yu K, Peng J, Zhang K, Xue H. Perceived overqualification and proactive behavior: the role of anger and job complexity. J Vocational Behav. 2023;141:103847. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103847

20. Dar N, Rahman W. Two angles of overqualification-The deviant behavior and creative performance: the role of career and survival job. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0226677. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226677

21. Peng X, Yu K, Kang Y, Zhang K, Chen Q. Perceived overqualification leads to being ostracized: the mediating role of psychological entitlement and moderating role of task interdependence. Career Dev Int. 2023;28(5):554–571. doi:10.1108/CDI-06-2022-0143

22. Huang C, Tian S, Wang R, Wang X. High-level talents’ perceive overqualification and withdrawal behavior: a power perspective based on survival needs. Front Psychol. 2022;13:921627. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921627

23. Sánchez-Cardona I, Vera M, Martínez-Lugo M, Rodríguez-Montalbán R, Marrero-Centeno J. When the job does not fit: the moderating role of job crafting and meaningful work in the relation between employees’ perceived overqualification and job boredom. J Career Assess. 2020;28(2):257–276. doi:10.1177/1069072719857174

24. Pindek S, Shen W, Gray CE, Spector PE. Clarifying the inconsistently observed curvilinear relationship between workload and employee attitudes and mental well-being. Work Stress. 2023;37(2):195–221. doi:10.1080/02678373.2022.2120562

25. Raihan MM, Chowdhury N, Turin TC. Low job market integration of skilled immigrants in Canada: the implication for social integration and mental well-being. Societies. 2023;13(3):75. doi:10.3390/soc13030075

26. Deng Y. The silver lining of perceived overqualification: examining the nexus between perceived overqualification, career self-efficacy and career commitment. Psychol Res Behav Managem. 2023;2681–2694. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S420320

27. Dar N, Ahmad S, Rahman W. How and when overqualification improves innovative work behaviour: the roles of creative self-confidence and psychological safety. Personnel Rev. 2022;51(9):2461–2481. doi:10.1108/PR-06-2020-0429

28. Bao Y, Zhong W. Public service motivation helps: understanding the influence of public employees’ perceived overqualification on turnover intentions. Australian J Public Admin. 2023;2023:1

29. Demir M, Dalgıç A, Yaşar E. How perceived overqualification affects task performance and proactive behavior: the role of digital competencies and job crafting. Int J Hospitality Tourism Admin. 2022;1–23. doi:10.1080/15256480.2022.2135665

30. Ma C, Lin X, Wei W, Wei W. Linking perceived overqualification with task performance and proactivity? An examination from self-concept-based perspective. J Business Res. 2020;118:199–209. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.041

31. Wu CH, Weisman H, Sung LK, Erdogan B, Bauer TN. Perceived overqualification, felt organizational obligation, and extra‐role behavior during the COVID‐19 crisis: the moderating role of self‐sacrificial leadership. Appl Psychol. 2022;71(3):983–1013. doi:10.1111/apps.12371

32. Duan J, Xia Y, Xu Y, Wu CH. The curvilinear effect of perceived overqualification on constructive voice: the moderating role of leader consultation and the mediating role of work engagement. Human Resour Manage. 2022;61(4):489–510. doi:10.1002/hrm.22106

33. Rebecca E, Jayawardana AK. Telecommuting on women’s work-family balance through work-family conflicts. J Telecommun Digital Economy. 2023;11(2):77–98. doi:10.18080/jtde.v11n2.694

34. Maynard DC, Joseph TA, Maynard AM. Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. J Org Behavi. 2006;27(4):509–536. doi:10.1002/job.389

35. Diener E, Napa Scollon C, Lucas RE. The evolving concept of subjective well-being: the multifaceted nature of happiness. Collected Works Ed Diener. 2009;2009:67–100.

36. Blau G. Testing a two-dimensional measure of job search behavior. Org beha human decis processes. 1994;59(2):288–312. doi:10.1006/obhd.1994.1061

37. Guan Y, Guo Y, Bond MH, et al. New job market entrants’ future work self, career adaptability and job search outcomes: examining mediating and moderating models. J Vocational Behav. 2014;85(1):136–145. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.05.003

38. Liu S, Huang JL, Wang M. Effectiveness of job search interventions: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):1009. doi:10.1037/a0035923

39. Bateman TS, Crant JM. The proactive component of organizational behavior: a measure and correlates. J Organizational Behav. 1993;14(2):103–118. doi:10.1002/job.4030140202

40. Becker TE. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: a qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Res Methods. 2005;8(3):274–289. doi:10.1177/1094428105278021

41. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

42. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. SAGE; 1991.

43. Ma C, Shang S, Zhao H, Zhong J, Chan XW. Speaking for organization or self? Investigating the effects of perceived overqualification on pro-organizational and self-interested voice. J Business Res. 2023;168:114215. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114215

44. Kim J, Park J, Sohn YW, Lim JI. Perceived overqualification, boredom, and extra-role behaviors: testing a moderated mediation model. J Career Dev. 2021;48(4):400–414. doi:10.1177/0894845319853879

45. Wu Z, Zhou X, Wang Q, Liu J. How perceived overqualification influences knowledge hiding from the relational perspective: the moderating role of perceived overqualification differentiation. J Knowledge Manage. 2023;27(6):1720–1739. doi:10.1108/JKM-04-2022-0286

46. Andel S, Pindek S, Arvan ML. Bored, angry, and overqualified? The high-and low-intensity pathways linking perceived overqualification to behavioural outcomes. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2022;31(1):47–60. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2021.1919624

47. Luksyte A, Bauer TN, Debus ME, Erdogan B, Wu C-H. Perceived overqualification and collectivism orientation: implications for work and nonwork outcomes. J Manage. 2022;48(2):319–349. doi:10.1177/0149206320948602

48. Zhang X, Ma C, Li Z. Building “Well-known Trademark”: the effect of perceived overqualification on career success.

49. Wu J, Zhang L, Wang J, Zhou X, Hang C. The relation between humble leadership and employee proactive socialization: the roles of work meaningfulness and perceived overqualification. Curr Psychol. 2023;1–13. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04734-7

50. Howard E, Luksyte A, Amarnani RK, Spitzmueller C. Perceived overqualification and experiences of incivility: can task i-deals help or hurt? J Occupational Health Psychol. 2022;27(1):89. doi:10.1037/ocp0000304

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.