Back to Journals » OncoTargets and Therapy » Volume 8

Clinicopathological significance of fascin-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer

Authors Ling X, Zhang T , Hou X, Zhao D

Received 10 March 2015

Accepted for publication 24 April 2015

Published 30 June 2015 Volume 2015:8 Pages 1589—1595

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S84308

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Faris Farassati

Xiao-Ling Ling,* Tao Zhang,* Xiao-Ming Hou, Da Zhao

Department of Oncology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University (The Branch Hospital of Donggang), Lanzhou, Gansu Province, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Purpose: Fascin-1 promotes the formation of filopodia, lamellipodia, and microspikes of cell membrane after its cross-linking with F-actin, thereby enhancing the cell movement and metastasis and invasion of tumor cells. This study explored the fascin-1 protein’s expression in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues and its relationship with clinical pathology and prognostic indicators.

Methods: Immunohistochemical analysis was used to determine the expression of fascin-1 in NSCLC tissues. We used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis to further verify the results. The fascin-1 expression and statistical method for clinical pathological parameters are examined by χ2. Kaplan–Meier method is used for survival analysis. Cox’s Proportional Hazard Model was used to conduct a combined-effect analysis for each covariate.

Results: In 73 of the 128 cases, NSCLC cancer tissues (57.0%) were found with high expression of fascin-1, which was significantly higher than the adjacent tissues (35/128, 27.3%). The results suggested that the high expression of fascin-1 was significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis (P=0.022) and TNM stage (P=0.042). The high fascin-1 expression patients survived shorter than those NSCLC patients with low fascin-1 expression (P<0.05). Univariate analysis revealed that lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, and fascin-1 expression status were correlated with the overall survival. Similarly, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, and fascin-1 expression status were significantly associated with the overall survival in multivariate analyses by using the Cox regression model.

Conclusion: The fascin-1 protein may be a useful prognostic indicator and hopeful new target for NSCLC patients.

Keywords: fascin-1, NSCLC, biomarker, prognosis

Introduction

The incidence of lung cancer remains high, and lung cancer ranks first in terms of cancer-related mortality. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 80% of all cases of lung cancer. NSCLC is usually discovered at advanced stages, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 15% among patients with advanced-stage NSCLC.1 Over the past few years, some progress has been achieved in diagnostic and treatment technologies for NSCLC; however, the survival rate of patients with NSCLC has not yet improved significantly. The infiltration of adjacent tissues and organ or lymph node metastasis are commonly discovered at the time of early diagnosis of NSCLC, and are the main reasons for treatment failure. Therefore, it is especially important to explore the etiology and pathogenesis of NSCLC, and to search for new therapeutic targets and markers.

As a member of the class of cytoskeleton proteins, fascin-1 promotes the formation of filopodia, lamellipodia, and microspikes of the cell membrane after cross-linking with F-actin, thereby enhancing the movement, metastasis, and invasion of tumor cells.2 A number of recent studies have shown that fascin-1 presents high expression in a variety of malignant tumors, such as breast cancers, pancreatic cancers, esophageal cancers, and colorectal cancers.3–6 The high expression of fascin-1 is often associated with the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of these tumors. To the best of our understanding, the expression of fascin-1 remains unclear in NSCLC. In order to assess the potential value of fascin-1 expression in clinical applications, this study explored fascin-1 expression in NSCLC tissues and its relationship with clinicopathological and prognostic indicators.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

NSCLC tumor tissues were obtained from 128 patients who were diagnosed and underwent complete surgical resection at The First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Lanzhou City, People’s Republic of China) from 2003 to 2007. All patients were diagnosed with primary NSCLC based on pathological evaluations. The study included 54 women and 74 men (median age: 61 years, range: 31–75 years). Cases were only selected for this study if follow-up examinations and clinical data were available. The patients did not receive any chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery. We excluded patients who had non-curative resection or died of postoperative complications. The histological grade and clinical stage of the tumors were defined according to the seventh edition of the TNM classification of the International Union Against Cancer.7 All specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The ethical committee of The First Hospital of Lanzhou University authorized the study, and each patient signed an informed consent form for research with resected samples.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemistry streptavidin-peroxidase method was adopted to examine paraffin sections. The immunohistochemical staining procedure was operated according to the kit’s instruction, as follows: the paraffin sections were dewaxed using the normal method, antigen retrieval was performed, 3% hydrogen peroxide was used for blocking endogenous peroxidase, goat serum was used for blocking, mouse anti-human fascin-1 monoclonal antibody was diluted (1:400; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA), secondary antibody and streptavidin-peroxidase complex were used, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine coloration and contrast staining were performed before sealing the slice. Known positive biopsies of normal tissues were employed as a positive control and phosphate-buffered saline was employed to provide a negative control (in place of the preliminary antibody).

Evaluation of fascin-1 protein expression

As viewed under a microscope at medium magnification (200×), five visual fields were randomly selected with a single-blind method for image reading (pathologists were blinded to clinical data). For each visual field, 200 tumor cells were counted, amounting to a total of 1,000 cells. Cells were divided into the following categories according to staining intensity: 0 points for no staining, 1 point for pale yellow staining, 2 points for yellowish-brown staining, and 3 points for brown staining. Tumor cells could also be divided based on the proportion of positive cells (ranging from 0% to 100%). In this study, if the product of the cell nucleus staining intensity and the cell nucleus positive percentage was greater than 0, we defined the specimen it as fascin-1 positive. Otherwise, it was defined as negative. In addition, we defined 0- and 1-point fascin-1 staining intensity as low expression, whereas 2- and 3- point staining were defined as high expression.

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Following the relevant instructions, the Trizol one-step method was used to extract the total RNA of the lung cancer and adjacent normal lung tissues before the obtained RNA was dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate water. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to verify RNA integrity, and an ultraviolet spectrophotometer was used to test purity and quantify results. The RNA absorbance fell within the range of 1.8–2.0. The amplification conditions were 95°C for 3 minutes, 94°C for 45 seconds, 53°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, and 35 cycles of 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products (5 μL) plus bromophenol blue (1 μL) were taken for the 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis examination. The results were transferred to video using a DNA gel imaging scanner, and band absorbance was measured with Gel-Pro Analyzer 3.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). In the course measurement, (brand gray scale ×area)/(reference gray scale × area) was employed as the parameter for fascin-1 mRNA expression levels, to quantify the relative fascin-1 product. The fascin-1 gene-specific primers for PCR amplification were as follows: 5′-CTGGCTACACGCTGGAGTTC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CTG AGTCCCCTGC TGTCTCC-3′ (reverse primer).

Western blot

Protein lysis buffer was applied to extract the protein in tissues. The bicinchoninic acid assay method was used to measure protein concentrations, collecting protein at 80 μg/hole to conduct 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferring the proteins to polyvinylidene difluoride film after electrophoresis separation. Skimmed milk powder solution (5%) was added and the system was sealed at room temperature for 1 hour. Subsequently, mouse anti-human fascin-1 monoclonal antibody and GAPDH mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; Yan Jing Reagent Company, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China ) were added, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. On the next day, the film was washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 three times for 10 minutes each. Next, 1:1,000-diluted goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G/horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody was added, a reaction was allowed at room temperature for 1.5 hours, and washing with Tween 20 was performed three times. After being developed with electrochemical luminescent reagent, ECL chemiluminescent reagent was used for autoradiography. The relative amount of fascin-1 is represented by the fascin-1/GAPDH gray-scale ratio, which was analyzed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Statistical methods

Fascin-1 expression and clinicopathological parameters were examined using the χ2 test. Fascin-1 mRNA expression in NSCLC tissues was compared with expression in normal adjacent tissues using the Mann–Whitney test (for two groups), the results were analyzed by 2−dCt method. The Kaplan–Meier method was employed for the survival analysis. In this study, the main outcome measures were overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival. We used Cox’s proportional hazards models to perform a combined-effect analysis for each covariate. The statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS 17.0 statistical software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of fascin-1 in NSCLC

Fascin-1 expression was detected in 128 primary NSCLC and adjacent tissues by immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical results showed that fascin-1 was mainly localized in the in the nucleus and cytoplasm of tumor (Figure 1). The results suggest fascin-1 have different levels of expression in NSCLC and adjacent tissues. In accordance with the evaluation criteria described previously, we found that in 73 of 128 cases, NSCLC cancer tissues (57.0%) had high expression of fascin-1, which significantly higher than the adjacent tissues (35/128, 27.3%). In order to further verify this result, we observed the expression levels of fascin-1 mRNA and protein using reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blot. The result indicated that the expression of fascin-1 was significantly higher in NSCLC tissues than that in adjacent tissues (P<0.01), (Figures 2 and 3).

| Figure 2 Fascin-1 mRNA was detected by RT-PCR. |

| Figure 3 Fascin-1 protein was detected by western blot analysis. |

Correlation of fascin-1 with clinicopathological parameters

Table 1 shows the relationships between fascin-1 expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with NSCLC. High expression of fascin-1 was significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis (P=0.022) and TNM stage (P=0.042). However, no statistically significant correlations were identified between high expression of fascin-1 and other clinicopathological characteristics, such as age, sex, smoking history, histological type, differentiation, and tumor size (P>0.05).

| Table 1 Correlation of clinicopathologic variables with fascin-1 protein in NSCLC |

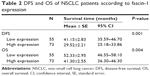

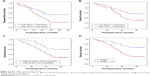

Prognostic significance of fascin-1 expression

Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the extent of fascin-1 expression (low vs high). Based on Kaplan–Meier curves, patients with high fascin-1 expression had shorter durations of survival than patients with low fascin-1 expression (P<0.05, Table 2 and Figure 4). A regression analysis was performed using the Cox’s proportional hazards model, which included all NSCLC clinical and pathological factors, as well as the fascin-1 expression status. Univariate analyses revealed that lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, and fascin-1 expression status were correlated with the OS. Similarly, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, and fascin-1 expression status were significantly associated with OS in the multivariate analyses that employed the Cox regression model (Table 3). According to the results of this regression analysis, high expression of fascin-1 is an independent prognostic factor for shorter survival in patients with NSCLC.

| Table 3 Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival |

Discussion

Fascin-1 protein is a kind of cytoskeletal protein, has a relative molecular mass of 55,000, and may bind specifically with F-actin.8 The fascin-1 gene is located on chromosome 7 q22.8 Fascin-1 protein is involved in the movement, transfer, and invasion of tumor cells. It generally has no expression in normal epithelial cells, but shows increased expression in many tumor cells.8,9 The thirty-ninth serine of fascin-1 protein is the site for the phosphorylation of protein kinase C, which can adjust the binding activity of fascin protein and actin.10 Direct, specific assemblage and disintegration of the actin filament changes the mobility of the tumor cells, by reducing the adhesive effect between the cells and other cells as well as between the cells and the matrix.11,12 In mouse tumor models, the expression of fascin-1 protein is elevated and the tumor cells’ abilities to invade and metastasize are strengthened.13 Another in vitro study has shown that high expression of fascin-1 protein can lead to protuberance of the cell membrane, decreasing the connection between the cells, and thereby enhance cell mobility for 15-fold.14 In the current study, fascin-1 protein showed higher expression in NSCLC tissues than in normal adjacent tissues. Fascin-1 protein was mainly located in the cell nucleus, and showed little expression in the cytoplasm.

Several speculations have been made regarding the molecular system by which fascin-1 expression is upregulated in tumor tissues.4,13–17 First, the protein coding products of fascin genes may be a variety of effect protein of C-erbB-2 on the cytoskeleton. C-erbB-2 has tyrosine protein kinase activity, which may activate the transcription of the fascin gene through certain nuclear factors and TATA core factors. Second, fascin-1 protein may be regulated by Wnt or para-insulin growth factor receptors. Third, fascin-1 protein expression may be regulated by multiple genes and transcriptional factors. However, space remains for additional in-depth studies on the identity of the channel that plays the main regulating role. Adams JC thinks that fascin-1 is absent in normal colonic epithelium, but its upregulation in colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas and its correlation with an aggressive clinical course has piqued the interest of many laboratories with research interests in cancer metastasis.6 In the study of Gao et al18 they used quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blot analyses to examine fascin-1 mRNA and protein levels in ten fresh laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma specimens and corresponding adjacent normal margin tissues. The results showed that high expression of fascin-1 was associated with poor prognosis, and they believe that fascin-1 may be prognostic of poor outcome with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma after surgery. In another study,4 overexpression of fascin-1 implies poorer tumor differentiation, advanced stage, and shorter survival rate in pancreatic and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinomas. The fascin-1 also has an abnormal expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hayashi et al propose that fascin-1 primarily acts as a migration factor associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and facilitates their invasiveness in combination with MMPs; it is a poor prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma.19

The present study examined the relationships between fascin-1 expression and other clinicopathological factors in cases of NSCLC. We detected fascin-1 in NSCLC and corresponding adjacent tissues, and we found that fascin-1 protein or mRNA was highly expressed in NSCLC tissues. In addition, high fascin-1 expression in NSCLC was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis and TNM stage. As shown by the Kaplan–Meier analysis, high fascin-1 expression was also significantly correlated with poor disease-free survival and OS. In addition to high fascin-1 expression, lymph node metastasis and advanced TNM stage were significantly associated with decreased survival. To determine independent prognostic factors, we performed univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to eliminate the effects of mixed factors that were relevant to prognosis in the statistical analysis. The results of these analyses showed that high expression of fascin-1 is an independent prognostic factor for shorter survival in patients with NSCLC. Our findings are similar to findings of the study of Pelosi et al.20 But should be noted that 89 cases of stage II and III of NSCLC patients were included in our study except 39 cases of patients, however only 220 with stage I NSCLC is included in the study of Pelosi et al.

To the best of our understanding, this article is the first English-language report of the prognostic implications of fascin-1 expression in NSCLC tissues. As supported by the results of our survival analysis, we suggest that fascin-1 protein may be a useful prognostic indicator for patients with NSCLC. Hopefully, it will also provide a new target in this group of patients.

Acknowledgments

The Science and Technology Project in Gansu Province of China (090NKCA126). The Project of Special technology research and development program in Gansu Province of China (1004TCYA023). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. | ||

Ma Y, Reynolds LE, Li A, et al. Fascin 1 is dispensable for developmental and tumour angiogenesis. Biol Open. 2013;2(11):1187–1191. | ||

Esnakula AK, Ricks-Santi L, Kwagyan J, et al. Strong association of fascin expression with triple negative breast cancer and basal-like phenotype in African-American women. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(2):153–160. | ||

Tsai WC, Lin CK, Lee HS, et al. The correlation of cortactin and fascin-1 expression with clinicopathological parameters in pancreatic and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma. APMIS. 2013;121(3):171–181. | ||

Cao HH, Zheng CP, Wang SH, et al. A molecular prognostic model predicts esophageal squamous cell carcinoma prognosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e106007. | ||

Adams JC. Fascin-1 as a biomarker and prospective therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(1):41–48. | ||

Chheang S, Brown K. Lung cancer staging: clinical and radiologic perspectives. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30(2):99–113. | ||

Ishikawa R, Sakamoto T, Ando T, Higashi-Fujime S, Kohama K. Polarized actin bundles formed by human fascin-1: their sliding and disassembly on myosin II and myosin V in vitro. J Neurochem. 2003; 87(3):676–685. | ||

Adams JC. Fascin protrusions in cell interactions. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14(6):221–226. | ||

De Arcangelis A, Georges-Labouesse E, Adams JC. Expression of fascin-1, the gene encoding the actin-bundling protein fascin-1, during mouse embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4(6):637–643. | ||

Kulasingam V, Diamandis EP. Fascin-1 is a novel biomarker of aggressiveness in some carcinomas. BMC Med. 2013;11:53. | ||

Yamashiro S. Functions of fascin in dendritic cells. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32(1):11–21. | ||

Ma Y, Li A, Faller WJ, et al. Fascin 1 is transiently expressed in mouse melanoblasts during development and promotes migration and proliferation. Development. 2013;140(10):2203–2211. | ||

Xu YF, Yu SN, Lu ZH, Liu JP, Chen J. Fascin promotes the motility and invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(40):4470–4478. | ||

Li D, Jin L, Alesi GN, et al. The prometastatic ribosomal S6 kinase 2-cAMP response element-binding protein (RSK2-CREB) signaling pathway up-regulates the actin-binding protein fascin-1 to promote tumor metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(45):32528–32538. | ||

Tan VY, Lewis SJ, Adams JC, Martin RM. Association of fascin-1 with mortality, disease progression and metastasis in carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:52. | ||

Jayo A, Parsons M, Adams JC. A novel Rho-dependent pathway that drives interaction of fascin-1 with p-Lin-11/Isl-1/Mec-3 kinase (LIMK) 1/2 to promote fascin-1/actin binding and filopodia stability. BMC Biol. 2012;10:72. | ||

Gao W, Zhang C, Feng Y, et al. Fascin-1, ezrin and paxillin contribute to the malignant progression and are predictors of clinical prognosis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50710. | ||

Hayashi Y, Osanai M, Lee GH. Fascin-1 expression correlates with repression of E-cadherin expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and augments their invasiveness in combination with matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(6):1228–1235. | ||

Pelosi G, Pastorino U, Pasini F, et al. Independent prognostic value of fascin immunoreactivity in stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(4):537–547. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.