Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Workplace Friendship is a Blessing in the Exploration of Supervisor Behavioral Integrity, Affective Commitment, and Employee Proactive Behavior – An Empirical Research from Service Industries of Pakistan

Authors Guohao L, Pervaiz S , Qi H

Received 17 July 2021

Accepted for publication 10 September 2021

Published 21 September 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1447—1459

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S329905

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Li Guohao,1 Sabeeh Pervaiz,1 He Qi2

1School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Sabeeh Pervaiz Email [email protected]

Purpose: Workplace friendships are typically complicated, serving various goals, imposing varying levels of expectation on the members, and representing the interaction among employees. Recent research has highlighted the multifaceted nature of friendship; however, the purpose of this study is to quantify the benefits of friendship at work. The study investigates the impact of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior. Moreover, it constructed a moderated mediation model based on attachment theory to examine the function of affective commitment as a mediator and workplace friendship as a moderator.

Methods: In three stages, 266 employee data from 20 Pakistani service industries were gathered (including seven banks, four educational institutes, five travel firms, and four telecom providers). Data on supervisor behavioral integrity, workplace friendship, affective commitment, employee proactive behavior, and demographics were collected between March and September 2020.

Findings: The findings indicated that supervisor behavioral integrity had a beneficial impact on employee proactive behavior. Affective commitment mediates the relation between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior. Furthermore, workplace friendship moderates the relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and affective commitment and the indirect impact of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior through affective commitment.

Conclusion: According to the findings of this study, workplace friendship is an essential informal aspect in any organization. Leadership as a formal organizational component would be greatly agitated even when employees have a low level of workplace friendship. Friendship in the workplace inspires employees to take action in order to succeed.

Keywords: supervisor behavioral integrity, affective commitment, employee proactive behavior, workplace friendship, attachment theory

Introduction

The importance of leaders’ words and deeds in exercising leadership behavior has been proven through extensive research. Supervisors must demonstrate professional quality and ethics in their daily management functions, such as fairness, honesty, and virtue. Simons originally defined supervisor behavioral integrity as “a perception of the consistency of a leader’s words and deeds from the employee’s perspective.” Employees are frequently involved in daily affairs with their supervisors, and their emotions and behaviors are primarily dependent on supervisor interaction. Employees can intuitively understand their direct superiors’ words and actions, reflecting leadership qualities.1 According to theoretical and practical groups, supervisory behavioral integrity is widely recognized as a commuting force in bringing positive outcomes to a firm through employee in-role performance, trust, and organizational citizenship behavior.2–4 Employees respect a trustworthy supervisor, and are motivated to go beyond the supervisor’s expectations. When a supervisor-employee relationship is built on credibility, integrity, and camaraderie, it inspires workers to engage in constructive behaviors like OCB.5 Nonetheless, deception by leaders is expected in the real world, and it can have a wide range of negative consequences for subordinates, teams, and even organizations. As a result, supervisor behavioral integrity will impact significant leadership exertion in the workplace.6 As a result, it’s critical to understand the influence mechanism and boundaries of supervisory behavioral integrity.

Leaders are known as agents of the organization because of employee-leaders relationship characteristics.7 In an organizational role, the leader offers the essential support and insight to promote a sense of belonging.2 Employees’ belief in management, affective commitment.8 job satisfaction,9 and intent to stay10 can all be influenced by behavioral integrity. Thus their turnover intentions decrease if employees have a strong emotional attachment to an organization. Furthermore, individuals with high levels of commitment are more likely to identify with the organization and participate actively in work. Employees’ affective or emotional attachment to their employer is referred to as affective commitment.11 Employees are more likely to acquire affective commitment if their managers encourage them to do so. They may respond to superiors’ ethical leadership behavior to increase their affective commitment to the leaders and organization.12,13 In a nutshell, when supervisors’ words and actions foster employee commitment and acceptance within a company, employees’ affective commitment to the supervisor and company may increase.

The term “workplace friendship” refers to an informal and deliberate relationship amongst members of an organization.14 This kind of relationship makes employees more connected to the organization and aids in minimizing negativity.15 Supervisor behavioral integrity is one of the organizational supports felt by workers, ensuring that employees recognize, trust, and respect the organization. Although supervisory behavioral integrity is a formal consideration, other informal factors such as workplace friendship can impact organizational outcomes. Employees who perform well and exhibit innovative behavior have a strong sense of belonging to their supervisors. Such employees are more likely to try new things and present their tasks efficiently and ideally.14,16 Workplace friendship motivates members to go the extra mile to achieve the desired goal,17 which benefits the organization.

Bowlby proposed attachment theory as “Attachment is characterized by specific, such as seeking proximity to the attachment figure when upset or threatened”.18 Attachment theory, according to this research, is a crucial theoretical framework for comprehending proactivity. According to research, employees who receive inconsistent support from their leaders are more likely to become preoccupied with their own attachment needs. Employees who have their behavioral attachment system activated may become dissociated from their leaders or engage in attention-seeking behaviors, both of which are counterproductive to work. Employees who are less emotionally connected to their bosses are less likely to trust them.19 On the other hand, Associated employees are hyper-sensitive and overly reliant on leaders’ approval.20 According to one study, even when leaders did not exhibit transformational characteristics, friendly, attached followers rated them as transformational.21 Similarly, subordinates who do not have a friendly attachment may be resistant to leadership as a result of previous unsupportive relationships (Keller, 2003). In conclusion, This study backs up the theory that workplace friendship will moderate the relationship between behavior integrity and proactive behavior.

The formal aspects of the workplace, such as leadership and management styles, have received ample attention from researchers.22,23 However, it is crucial to capitalize on the informal workplace characteristics. As a result, the focus of this study is on the moderating effect of workplace friendship, an informal component that necessitates further research into the formal effect process. This study adds to the current body of knowledge by thoroughly investigating the link between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior based on attachment theory. The addition of affective commitment as a mediator and workplace friendship as a moderator strengthens the overall relationship. Furthermore, this study is significant for organizations to understand the emotional state of workers as supervisors, develop a clear feeling of affective commitment and promote proactive employees’ behavior.

Hypotheses Development

Supervisor Behavioral Integrity and Employee Proactive Behavior

Behavioral integrity in the workplace has traditionally been regarded as a positive factor, with roots in transformational and charismatic leadership styles. Employees are eager to put their faith in leaders to influence their attitudes and behavior.24 Previous research has suggested that improving psychological safety and job roles flexibly will help leaders endorse employees’ proactive behavior.10,25,26 Strauss et al27 explained the readiness of employees to do the work and try many new things in good relations with the supervisor. Integrity in leadership fosters a work environment where employees are valued. They have their psychological needs met, and they are more likely to realize and achieve their goals.28 Workers can even be motivated to actively contribute to themselves and the organization by their leaders’ integrity, compassion, and ethical behavior, encouraging them to go beyond their responsibilities.

Emotional communications are involved in the relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and proactive employee behavior. The outcomes are more productive if expectations and responsibilities are clear, loyalty and faith are stronger, and relationships between employees and organizations are robust.29 To strengthen employees’ deep organizational support feelings, organizations implement ethical activities, rules of equality, and a caring environment. To ensure long-term growth in a harmonious and trustworthy working environment, employees must take proactive measures.30 Employees actively promote the interaction with work or organization when their emotional fulfillment needs are met, increasing job satisfaction and organizational commitment. It establishes a clear emotional commitment, which will significantly impact employees’ proactive behavior.31 Employees satisfied with their supervisors show extra dedication and loyalty to the organization.32,33 Leaders with moral personality qualities motivate workers to reach their full potential, urge them to take on additional organizational tasks, and inspire them to confront difficulties.34

Substitutes are qualities or variables that can be used to replace certain leadership behaviors. According to Kerr and Jermier35 in their Substitutes for Leadership Theory, contextual variables can influence the effects of leadership. Contextual variables such as the work environment, task, and employee characteristics can compensate for or cancel out the effects of a leader’s actions. The moral behavior of leaders shapes the altruistic environment. As a result, the altruistic environment can be used as a contextual variable, as suggested by the substitutes for leadership theory.35,36 Assume that, as a result of their emotional commitment, employees engage in proactive behavior toward the organization. Therefore, the leaders do not have to make further efforts to encourage them to show positive behavior. This perspective also addresses the point that

employees who perceive their supervisors to have behavioral integrity are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors than supervisors who lack behavioral integrity.

Therefore, this research explored the effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior by expanding the above research paths and put forward the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Supervisor behavioral integrity positively affects employee proactive behavior.

Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

Affective commitment is a psychological state formed by employees’ evaluation of the organizational environment, which will affect employees’ predictions of corporate events and work results.37 When treated respectfully during interactions with superiors, employees with clear personal commitment comprehend the company’s aims and actively contribute to the organization, demonstrating better organizational recognition, loyalty, and responsibility. Therefore, the consistency in the leader’s words and deeds is the most reasonable and adequate indicator for assessing employees’ affective commitment and is highly dependent on respect and trust between leader and employee.38 This trust can create a harmonious environment for the employees, resulting in a high-quality “leader-member” relationship.39

Discussion on affective commitment in the current academic circles mainly focused on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior.40–42 An employee’s psychological state is a prerequisite for proactive behavior, motivating subordinates to invest high enthusiasm in the work process. Employees recognized and rewarded for meeting their emotional needs and have a high degree of trust exhibit a more favorable work attitude and behavior. It can stimulate employees’ extra-role actions, encourage employees to complete work tasks, and achieve organizational goals.43,44

Managers may improve employees’ emotional commitment and psychological contract by providing an ethical workplace and developing a pleasant organizational climate, enhancing employee proactive behavior.45 Organizations that fostered a caring and established ethical environment instill a sense of security and fairness in their employees, resulting in a desire to proactively respond to the organization’s treatment with a positive work attitude, as well as stimulate professional commitment and constructive behavior.12,46 When employees perceive supervisor behavioral integrity at a low level, the resulting role ambiguity and role conflict will restrain employees from forming an emotional attachment.47

In summary, Affective commitment has a mediating effect on supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior. Based on the above discussion, this research proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Affective commitment mediates the relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior.

Moderated Mediation of Workplace Friendship

Elton Mayo48 brought workplace friendships to light; he was the first to advocate the role of emotional factors in determining employee behavior and argue that the extent to which employees received social satisfaction in the workplace has been the most influential on productivity. Workplace friendship was initially defined as “A unique, non-compulsive interpersonal relationship formed based on voluntary principles”.49 Apart from the official task assigned, this type of friendship refers to an interpersonal relationship that employees develop. This encourages employees to form responsibilities and obligations to their coworkers and supervisors voluntarily, thereby strengthening their emotional bonds with other company members.16 Research suggests that workplace friendship can improve an organization’s performance because friendly staff like to help each other with tasks, communicate with moral behaviors, have limited communication problems, and can thus increase efforts and production rates.50

Healthy supervisor-employee relationships are built on the foundations of friendship, respect, and trust. These qualities can help both the supervisor and the employee, as well as the entire workplace. According to previous research, supervisory behavioral integrity significantly impacts employee proactive behavior, so the relationship is strengthened when workplace friendship exists between supervisors and employees. This friendship can buffer during difficult times, encouraging employees to stay proactive and trust their supervisor.15,51 Employees’ attachment and emotional connection to the organization may be strengthened through workplace friendship, which improves their feeling of belonging and promotes their commitment to the firm.17 On the one hand, employees take the initiative to act based on their leaders’ integrity behaviors; on the other, their actions are strengthened by friendship at the workplace. To put it another way, employees will exhibit positive behaviors as a result of improved emotional relationships.

Employees must demonstrate a professional and more profound connection with their bosses, while supervisors must treat their employees with respect and dignity.52 Affective commitment can be characterized as employees’ willingness to assist in the achievement of the organization’s goals and their levels of identification, loyalty, and involvement. Employees develop a network of relatively familiar relationships, which increases their trust and boosts overall productivity. This idea of friendship fosters the innate drive to work.53 Strengthening employees’ internal identity perceptions and consolidating affective commitment is an important part of the organization. As a result, employees will take several steps to help the company grow.54

The affective commitment brought by interpersonal relationships’ satisfaction in the workplace will also promote employees’ positive work behavior. According to Hui et al41 workplace friendship provides emotional support to employees, improves work attitudes, and positively impacts work-related outcomes such as proactive behavior. As a result, it provides emotional support to employees to effectively achieve institutional participation, creates a supportive environment, and improves employees’ job satisfaction.55 The main structure of Bowlby’s18 attachment theory is the system of affection, which motivates people to perform better under the support of others. Hence a better and more profound connection will lead to a high relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and proactive employee behavior.56

Based on the above discussion, this research proposed workplace friendship will moderate the overall relationship, hence proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Workplace friendship moderates the indirect relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and proactive behavior through affective commitment.

To sum up, this research aims to discuss the impact of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior based on attachment theory. Also, it discusses affective commitment (mediating variable) and workplace friendship (moderating variable) in the moderated mediation model. The theoretical model can be seen in Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Methodology

Data Collection

The survey was developed as a web link and sent to HR managers in 20 different service industries (including 7 banks, 4 educational institutes, 5 travel companies, and 4 telecom companies). 18 questionnaires were distributed to corresponding HR managers for distribution among employees. Because the questionnaire had to be completed in three stages with time intervals, each respondent was assigned a code.

The first round of data collection, which began in March 2020, focused on workplace friendship, supervisor behavioral integrity, and demographic information. A total of 360 questionnaires were mailed, with 322 being returned. Incomplete and influenced questionnaires were discarded at each stage of evaluating the returned questionnaires. As a result, 316 legitimate questionnaires were obtained during Phase One. The second round of data collection on affective commitment was completed in July 2020. 316 questionnaires were distributed to employees, and 303 were returned. During this time period, the legitimate questionnaire recorded a total of 299. The third phase of data collection began in September 2020. A total of 299 questionnaires were distributed in order to assess employees’ proactive behavior, with 272 responses. When the questionnaires were finally validated, 266 valid data samples were obtained, accounting for 73.89% of all valid data samples.

All research processes have been meticulously monitored and standardized. Participants were required to complete the survey items consistently over the course of the allotted time, and the research objective was communicated. As a result, the acquired data’s neutrality, confidentiality, and legitimacy were all ensured to some extent.

Measures and Variables

The average number was calculated after respondents reported a Likert 5-point scoring method between 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated that employees were in a better situation.

This research measured supervisor behavioral integrity through the seven items scale developed by Simons et al.57 One of the items from the scale states, “My manager delivers on a promise.” Respondents were asked to rate the point on a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate a better understanding of supervisor behavior integrity. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability for the scale was 0.862.

Allen and Mayers37 affective commitment subscale was coupled with continuous commitment and normative commitment to producing an organizational commitment full scale, which was employed in this study. This subscale has six items, and one of the items states, “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.” This research used a Likert 5-point scale to measure affective commitment. Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.718 in this research, which met the basic standard of psychometrics.

For measuring employee proactive behavior, the Frese et al58 scale was used in this research, having a Cronbach Alpha value of 0.847. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale. One of the seven items states, “Whenever the opportunity arises, I will take the initiative.”

The workplace friendship scale was developed by Nielson et al59 and revised by Cho et al.8 Five items are used to measure friendship opportunity, and four items are used to measure friendship strength. One of the items states, “I can work with my colleagues to solve problems.” These two dimensions together explained the existence and the extent of friendship in the workplace. This research’s measurement showed that Cronbach’s Alpha of the scale was 0.853 and attained the psychometric standard.

Control Variables

Gender, age, education, tenure, and income were among the demographic information recorded. According to a review of the existing literature, this demographic research information may affect employees’ mental state, and behavioral responses can significantly impact the study’s results.60,61 As a result, during the analysis process, demographic information should be controlled.

Ethical Issues

This study was carried out according to the recommendations of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct by the American Psychological Association (APA). The research was granted access by the ethics committee of the School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, People’s Republic of China, and COMSATS University, Pakistan. The participating companies’ HR departments were informed, and all the participants provided the written consent. The research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Findings and Discussions

The proportion of male employees in the effective sample subject was 54.14%. Employees aged 20–25 made up 33.08%, employees aged 26 to 30 accounted for 11.28%, employees aged 31 to 35 accounted for 36.84%, employees aged 36 to 40 made up 17.67%, and employees aged 41 and up made up 1.13%. The proportion of bachelor’s degree and above was 92.86%. The proportion of tenure in the current company below one year was 9.77%, the proportion of 1 to 3 years was 39.47%, the proportion of 4 to 7 years was 40.98%, the proportion of 8 to 11 years was 8.27%, the proportion for 12 years and above was 1.50%. The proportion of earning 15,000–20,000 per month was 53.76%, the proportion of earning 21,000–35,000 per month was 16.54%, the proportion of earning 36,000–50,000 per month was 19.55%, the proportion of earning 51,000–100,000 per month was 5.64%, and the proportion for more than 100,000 was 4.51%. In contrast, 137 employees were reported as having the same gender as their direct supervisors and accounted for 51.50% of the total samples. The majority of employees stayed with the same company for more than two years, and a significant proportion of supervisors stayed for more than four years.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results are exhibited in Table 1: Supervisor behavioral integrity is positively related to employee proactive behavior (r=0.315, p<0.001), supervisor behavioral integrity is positively related to affective commitment (r=0.243, p<0.001), affective commitment is positively related to employee proactive behavior (r=0.642, p<0.001), workplace friendship is positively related to affective commitment (r=0.191, p<0.01) and employee proactive behavior (r=0.196, p<0.05). As a result, the above findings preliminarily confirmed the research’s theoretical hypothesis.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis |

Measurement Models

Harmon’s one-factor test was conducted to check common method deviation. An unrotated factor analysis was performed on all items and extracted four factors with values greater than 1. The cumulative variance was reported at 65.4%. The first-factor variance was recorded as 21.2%, far below the standard empirical value of 50%. The results supported no single factor can explain most variation,62 hence there was no serious common method deviation. Furthermore, every factor loading is higher than 0.50, stating that the variables have good convergent validity.

To assess discriminant validity, this study used the Fornell Larcker test. Supervisor behavioral integrity (0.740), affective commitment (0.645), employee proactive behavior (0.723), and workplace friendship (0.687) have more significant AVE square root values than other correlation coefficients in the same rows and columns. This implies that the variables have a significant level of discriminant validity.

This research also conducted CFA using the AMOS to check structure validity among four variables. Table 2 shows that the four-factor model’s fitting index has reached the ideal standard and is significantly better than other factor models, indicating that the variables have good structure validity.

|

Table 2 CFA |

Hypothesis Testing

Process Macro has recently received a lot of attention and is a useful tool for testing hypotheses.63,64 The theoretical hypotheses are classified as direct effect, indirect effect, and moderated mediation. The Hayes Models 4 and 7 were used in this study to investigate the direct, indirect, and moderated mediation effects.65 Condition process modeling was used to investigate the direct effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior, the mediating effect of affective commitment between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior (indirect effect), and the moderating effect of workplace friendship in moderated mediation. The findings are summarized in Table 3: Supervisor behavioral integrity had a direct effect of 0.170 on employee proactive behavior. The values for CI=[LLCI=0.064, ULCI=0.277] at 95% confidence interval did not include 0. As a result, the direct effect has reached a significant level and supports Hypothesis 1. On the other hand, through the mediating effect of affective commitment, the indirect effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior was 0.161. The indirect effect has reached a significant level, as the 95% confidence interval CI=[LLCI=0.0793, ULCI=0.259] did not include 0. As a result of the findings, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

|

Table 3 Main Effect |

Prior to testing the moderated mediation model, the moderating role of workplace friendship between supervisor behavioral integrity and affective commitment should be investigated. The interaction item of supervisor behavioral integrity and workplace friendship has a significant positive impact on affective commitment (=0.079, p0.05), as shown in Table 4, Model 4. Supervisor behavioral integrity has a significant positive impact on affective commitment (=0.227, p0.001), with both coefficients pointing in the same direction. This investigation found that workplace friendship has a stronger moderating effect on the relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and affective commitment.

|

Table 4 Moderating Role |

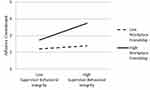

Subsequently, this study created a schematic diagram of the interaction effect to visualize the direction and intensity of the workplace friendship moderating effect. As shown in Figure 2, When there is a low level of workplace friendship, the regression slope of supervisor behavioral integrity to affective commitment is gentler and lower. When there is a high level of workplace friendship, the regression slope of supervisor behavioral integrity to affective commitment is more inclined and higher. The increased moderating effect of workplace friendship has been graphically evidenced.

|

Figure 2 Workplace friendship moderating effect. |

The Hayes Model 7 was used to examine the moderating effect of workplace friendship in the indirect effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior via affective commitment. The indirect effect is not significant in the case of low workplace friendship (95% confidence interval CI=[LLCI=−0.065, ULCI=0.193], which includes 0). However, the indirect effect is significant in high workplace friendship (95% confidence interval CI=[LLCI=0.128, ULCI=0.375], which does not include 0). As a result, the moderated mediation model is significant, and the results support Hypothesis 3. The results of the moderated mediation model are shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Moderated Mediation |

Discussions

Previous studies suggested that supervisor behavioral integrity positively affects both employees and organizations.56 The outcomes of this research are in line with previous studies. When employees are treated with dignity and integrity, their faith in the company grows. They behave as excellent soldiers for the organization, according to PaustianUnderdahl and Halbesleben 2014.66 Integrity in the workplace can take various forms. However, it primarily relates to outstanding character qualities and work ethics, such as intellectual honesty, trustworthiness, reliability, and loyalty. According to the findings, integrity may lead to ethical thinking and better decision-making, leading to improved work performance. If integrity is not a workforce trait, the entire business will be plagued by severe internal issues such as corruption, which will finally bring the company apart.

Secondly, this study discovered that affective commitment has a mediation function between supervisor behavioral integrity and proactive employee behaviors. Which is to state, supervisor behavioral integrity can influence workers proactive behavior directly and indirectly through increasing employees’ affective commitment to the organization. Many studies show that someone’s emotional state has a big influence on the overall personality. As the company’s representative, the supervisor has the most frequent contact with employees, and leadership behavior directly impacts employees’ affective commitment to the company. Employees’ esteem, support, and insight are reflected in management’s concern, assistance, and empathy. When guided by the concept of reciprocity, especially in Pakistani culture, which places a high value on human sentiments, it is easier to inspire workers’ appreciation and return, improve their emotional return to supervisors and organizations, and thus boost their initiative at work.

Finally, the findings suggested that when there is a low level of workplace friendship, supervisor behavioral integrity to affective commitment is lower, and when there is a high level of workplace friendship, it is higher. To support our reasoning, we used attachment theory in this study. Attachment theory has recently been proposed as a promising theoretical framework for investigating the effects of workplace friendship.17 Specifically, unlike previous research that focused on the formal aspects of the workplace, this research included workplace friendship as an informal variable that can significantly impact. On the other hand, for employees who have a poor sense of workplace friendship, the effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on affective commitment will be weaker, even insignificant, and employees proactive behavior will be reduced. This is in line with substitute theory, which states that the substitute element’s effect may be stronger than the original element’s and can exert an effect in place of the leadership.

To summarize the results of this study revealed supervisor behavioral integrity’s relationship on employee proactive behavior, supplementing the positive influence results related to supervisor behavioral integrity. Employees with a higher level of supervisor behavioral integrity are more likely to engage in proactive behavior. On the other hand, employees with a lower level of supervisor behavioral integrity are more likely to refrain from engaging in proactive behaviors, which refers to low-intensity retaliation. This study also discovered a link between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior via affective commitment. Employees can have a high affective commitment because of their supervisor’s behavioral integrity, leading to proactive behavior. As a result, this study complemented how an employee’s behavioral reaction to a supervisor’s behavioral integrity supplemented affective commitment’s theoretical and practical research findings.28,38

Theoretical Contributions

This research explicated that workplace friendship can positively moderate supervisor behavioral integrity on employee proactive behavior through affective commitment in a moderated mediation model. Boğan and Dedeoğlu66 proposed that employees who were seriously engaged in workplace friendship can enhance their professional and emotional resources obtained from other organizational members. They will report positive emotions, perform well to try out new affairs at work, and add career success chances. Nevertheless, empirical test results also showed that workplace friendship would moderate the formal factors’ (supervisor behavioral integrity) influence process as an informal factor in the workplace. When the informal factor is at a low level, even the formal factors are not operative, which is also consistent with substitute for leadership theory. Hence, this study settles workplace friendship as a blessing. It helps create deep ties to people, enhances a person’s overall satisfaction, and increases the productivity and commitment culture in the organization. The claim of this study of friendship as a blessing is consistent with the previous researchers.67 According to attachment theory, the effect of supervisor behavioral integrity on affective commitment and employee proactive behavior is more prominent for employees who have a better sense of workplace friendship. In contrast, When there is a low sense of workplace friendship, the mediating mechanism of affective commitment is weakened, and the influence process of formal factor (supervisor behavioral integrity) effects on employee proactive behavior is insignificant.

Pakistan’s service sector is one of the country’s fastest-growing industries. This sector is primarily made up of private companies that rely heavily on good relationships between employees and supervisors to retain employees and make them proactive for the company. The majority of research in the Pakistan service sector has focused on the formal side of the organizational setting, and there is still much room for research in other informal aspects of organization. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to look into these sets of variables, particularly workplace friendship in Pakistan’s service sector. This study validates Wu and Parker56 assertion, based on attachment theory, that the supervisor plays a critical role in the development of proactive employee behavior.

Practical Implications

Interestingly, some employees perceived low supervisor behavioral integrity during the survey process, but they remained committed to their jobs. Such employees see proactive behavior as a part of their workplace obligation, regardless of their direct supervisor’s behavior. This sense of responsibility stems from a better personal relationship with leaders or a positive work attitude that allows them to demonstrate their competence, exceed supervisory expectations, and reduce the risk of punishment from supervisors. On the other hand, workplace friendship has received both positive and negative support as a relevant and influential organizational unit in the workplace. Encouragement of workplace friendship development comes with many risks, especially when workplace friendship is negative. As a result of the two-sided nature of workplace friendship, organizations should not invest heavily in its development.

Employees who perceive a supervisor’s lack of behavioral integrity limit their proactive behavior and are less likely to encourage further development. Many organizations now operate in a highly competitive market, and supervisors may change their instructions to employees on a regular basis. Objective setbacks caused by rising competitive pressure may cause them to behave in a specific way that leads to duplicity. They may also have a negative impact on employee recognition and affective commitment to the organization, resulting in less proactive behavior. This study advocates for supervisor behavioral integrity to be endorsed and encouraged in the workplace.

Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate these variables in Pakistan’s service industry sector, emphasizing the importance of supervisor behavioral integrity in fostering employee work enthusiasm and organizational development. The major contribution of this study is to the attachment theory literature by investigating the mediating effect of affective commitment and the moderating effect of workplace friendship in the process of supervisor behavioral integrity influencing employee proactive behavior. This study primarily supported the importance of workplace friendship in the organization. Workplace friendship can meet employees’ social needs, thereby improving their workforce through emotional attachment.

Limitations and Future Directions

This research also inevitably has some limitations. Firstly, this research collected time-lagged data. A further vertical investigation should be carried out for a relatively long period to determine a direct causal relationship between supervisor behavioral integrity and employee proactive behavior. The test results obtained from the collected data will be more reliable.

Second, this study only gathered information from employees. Employees may rate themselves higher in order to create better impression management. Future research should include data collection from supervisors and employees to form pairing samples. This type of multilevel research will aid in a better understanding of this relationship.

Thirdly, other control variables related to employee proactive behavior are not set except for the demographic information factors. An individual’s sense of control over performance payment and clear perception of fair distribution are conducive to maintaining high proactive behavior.12 Job competence, self-efficacy, and an appropriate atmosphere can raise an employee’s perception of organizational justice and affective commitment.46 Employee proactive behavior can be influenced by a cooperative and service environment, which can contribute to positive interpersonal communication, enhance interpersonal trust, and improve the reliability of mutual assistance between members.2 Furthermore, leader duplicity is more likely to manifest itself only in a small number of employees. According to the leader’s point of view, supervisor behavioral integrity is linked to employees’ role definition. Future research should look into the impact of employees’ role definitions from a leader’s perspective.

Finally, this study did not look into the perspectives of employees on supervisory behavior integrity. Employees, for example, will not be offended if they do not perceive the positive effects of supervisor behavioral integrity on themselves. This phenomenon can also be explained by incorporating inference theory. Future research should focus on the above issues to better understand how employees perceive supervisory behavioral integrity.

Ethical Issues

This study was carried out according to the recommendations of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct by the American Psychological Association (APA). The research was granted access by the ethics committee of the School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, People’s Republic of China, and COMSATS University, Pakistan. The participating companies’ HR departments were informed, and all the participants provided the written consent. The research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the Editor of Psychology Research and Behavior Management and the reviewers for providing us with insightful suggestions to make this work more valuable.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study received funding from Jiangsu University & JiangSu Haicore Technology Joint Stock Co., LTD. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

1. Simons T. Behavioral integrity: the perceived alignment between managers’ words and deeds as a research focus. Organ Sci. 2002;13(1):18–35. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.1.18.543

2. Choi Y, Yoon DJ, Kim D. Leader behavioral integrity and employee in-role performance: the roles of coworker support and job autonomy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4303. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124303

3. Vogelgesang GR, Crossley C, Simons T, Avolio BJ. Behavioral integrity: examining the effects of trust velocity and psychological contract breach. J Bus Ethics. 2020:1–16. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04497-2

4. Gatling A, Molintas DHR, Self TT, Shum C. Leadership and behavioral integrity in the restaurant industry: the moderating roles of gender. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour. 2020;19(1):62–81. doi:10.1080/15332845.2020.1672249

5. Zhang Y, Liu X, Xu S, Yang L-Q, Bednall TC. Why abusive supervision impacts employee OCB and CWB: a meta-analytic review of competing mediating mechanisms. J Manage. 2019;45(6):2474–2497.

6. Peng H, Wei F. Trickle-down effects of perceived leader integrity on employee creativity: a moderated mediation model. J Bus Ethics. 2018;150(3):837–851. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3226-3

7. Ashforth BE, Schinoff BS, Brickson SL. My company is friendly,” “Mine’sa Rebel”: anthropomorphism and shifting organizational identity from “What” to “Who. Acad Manag Rev. 2020;45(1):29–57. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0496

8. Cho Y, Shin M, Billing TK, Bhagat RS. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and affective organizational commitment: a closer look at their relationships in two distinct national contexts. Asian Bus Manag. 2019;18(3):187–210. doi:10.1057/s41291-019-00059-1

9. Stankovska G, Angelkoska S, Osmani F, Grncarovska SP. Job motivation and job satisfaction among academic staff in higher education. Bulg Comp Educ Soc. 2017. doi:10.5296/ijhrs.v7i4.12029

10. Simons T, McLean Parks J, Tomlinson EC. The benefits of walking your talk: aggregate effects of behavioral integrity on guest satisfaction, turnover, and hotel profitability. Cornell Hosp Q. 2018;59(3):257–274. doi:10.1177/1938965517735908

11. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R, Armeli S. Affective commitment to the organization: the contribution of perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(5):825. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

12. Koopman J, Scott BA, Matta FK, Conlon DE, Dennerlein T. Ethical leadership as a substitute for justice enactment: An information-processing perspective. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(9):1103. doi:10.1037/apl0000403

13. Cheng C-Y, Jiang D-Y, Cheng B-S, Riley JH, Jen C-K. When do subordinates commit to their supervisors? Different effects of perceived supervisor integrity and support on Chinese and American employees. Leadersh Q. 2015;26(1):81–97. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.002

14. Pillemer J, Rothbard NP. Friends without benefits: Understanding the dark sides of workplace friendship. Acad Manag Rev. 2018;43(4):635–660. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0309

15. Mao H-Y, Hsieh A-T, Chen C-Y. The relationship between workplace friendship and perceived job significance. J Manag Organ. 2012;18(2):247. doi:10.5172/jmo.2012.18.2.247

16. Cao F, Zhang H. Workplace friendship, psychological safety and innovative behavior in China. Chinese Manag Stud. 2020;14:661–676. doi:10.1108/CMS-09-2019-0334

17. Coetzee M, Ferreira N, Potgieter I. Perceptions of sacrifice, workplace friendship and career concerns as explanatory mechanisms of employees’ organisational commitment. SA J Hum Resour Manag. 2019;17(1):1–9. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v17i0.1033

18. Bretherton I. The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Dev Psychol. 1992;28(5):759. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759

19. Han GH, Harms PD, Bai Y. Nightmare bosses: The impact of abusive supervision on employees’ sleep, emotions, and creativity. J Bus Ethics. 2017;145(1):21–31. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2859-y

20. Wu C-H, Parker SK, De Jong JPJ. Need for cognition as an antecedent of individual innovation behavior. J Manage. 2014;40(6):1511–1534.

21. Buil I, Martínez E, Matute J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: the role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;77:64–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.014

22. Obiekwe N. Employee motivation and performance; 2016.

23. Mulki JP, Caemmerer B, Heggde GS. Leadership style, salesperson’s work effort and job performance: the influence of power distance. J Pers Sell Sales Manag. 2015;35(1):3–22.

24. Williams R

25. Rogiest S, Segers J, van Witteloostuijn A. Matchmaking in organizational change: Does every employee value participatory leadership? An empirical study. Scand J Manag. 2018;34(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2017.05.003

26. Fuller B, Marler LE, Hester K, Otondo RF. Leader reactions to follower proactive behavior: Giving credit when credit is due. Hum Relations. 2015;68(6):879–898. doi:10.1177/0018726714548235

27. Strauss K, Parker SK, O’Shea D. When does proactivity have a cost? Motivation at work moderates the effects of proactive work behavior on employee job strain. J Vocat Behav. 2017;100:15–26. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.001

28. Kacmar KM, Tucker R. The moderating effect of supervisor’s behavioral integrity on the relationship between regulatory focus and impression management. J Bus Ethics. 2016;135(1):87–98. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2464-5

29. Andersson R. Employee communication responsibility: Its antecedents and implications for strategic communication management. Int J Strateg Commun. 2019;13(1):60–75. doi:10.1080/1553118X.2018.1547731

30. Domino MA, Wingreen SC, Blanton JE. Social cognitive theory: the antecedents and effects of ethical climate fit on organizational attitudes of corporate accounting professionals—a reflection of client narcissism and fraud attitude risk. J Bus Ethics. 2015;131(2):453–467. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2210-z

31. Khattab J, Van Knippenberg D, Pieterse AN, Hernandez M. A network utilization perspective on the leadership advancement of minorities. Acad Manag Rev. 2020;45(1):109–129. doi:10.5465/amr.2015.0399

32. Lee SM, Farh CIC. Dynamic leadership emergence: Differential impact of members’ and peers’ contributions in the idea generation and idea enactment phases of innovation project teams. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(3):411. doi:10.1037/apl0000384

33. Saleem MA, Bhutta ZM, Nauman M, Zahra S. Enhancing performance and commitment through leadership and empowerment. Int J Bank Mark. 2019;37:303–322. doi:10.1108/IJBM-02-2018-0037

34. Rahman S, Batool S, Akhtar N, Ali H. Fostering individual creativity through proactive personality: a multilevel perspective. J Manag Sci. 2015;9:2.

35. Kerr S, Jermier JM. Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1978;22(3):375–403. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(78)90023-5

36. Howell JP, Dorfman PW, Kerr S. Moderator variables in leadership research. Acad Manag Rev. 1986;11(1):88–102. doi:10.5465/amr.1986.4282632

37. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

38. Nadeem K, Akram W, Ali HF, Iftikhar Y, Shamshad W. The relationship between work values, affective commitment, emotional intelligence, and employee engagement: a moderated mediation model. Eur Online J Nat Soc Sci. 2019;8(3):469–482.

39. Halbesleben JRB, Leroy H, Dierynck B, et al. Living up to safety values in health care: The effect of leader behavioral integrity on occupational safety. J Occup Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):395. doi:10.1037/a0034086

40. Anand S, Vidyarthi P, Rolnicki S. Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviors: Contextual effects of leader power distance and group task interdependence. Leadersh Q. 2018;29(4):489–500. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.002

41. Hui C, Lee C, Wang H. Organizational inducements and employee citizenship behavior: the mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of collectivism. Hum Resour Manage. 2015;54:439–456. doi:10.1002/hrm.21620

42. Özduran A, Tanova C. Manager mindsets and employee organizational citizenship behaviours. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2017;10:23–27.

43. van der Hoek M, Groeneveld S, Kuipers B. Goal setting in teams: goal clarity and team performance in the public sector. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2018;38:472–493. doi:10.1177/0734371X16682815

44. Robescu O, Iancu A-G. The effects of motivation on employees performance in organizations. Valahian J Econ Stud. 2016;7:49–56. doi:10.1515/vjes-2016-0006

45. Yi C, Yan A. Research on high performance work systematic influences on employees work behaviour in environmental company. Ekoloji. 2018;27:337–349.

46. Zagladi AN, Hadiwidjojo D, Rahayu M. The role of job satisfaction and power distance in determining the influence of organizational justice toward the turnover intention. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2015;211:42–48. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.007

47. Chen C-HV, Yuan M-L, Cheng J-W, Seifert R. Linking transformational leadership and core self-evaluation to job performance: the mediating role of felt accountability. North Am J Econ Financ. 2016;35:234–246. doi:10.1016/j.najef.2015.10.012

48. Mayo E. The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization, Including, as an Appendix: The Political Problem of Industrial Civilization. Harvard: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration; 1945.

49. Wright PH, Scanlon MB. Gender role orientations and friendship: Some attenuation, but gender differences abound. Sex Roles. 1991;24(9–10):551–566. doi:10.1007/BF00288413

50. Bandura A. The anatomy of stages of change. Am J Heal Promot. 1997;12(1):8–10. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.8

51. Yu-Ping H, Chun-Yang P, Ming-Tao C, Chun-Tsen Y, Qiong-yuan Z. Workplace friendship, helping behavior, and turnover intention: the meditating effect of affective commitment. Adv Manag Appl Econ. 2020;10(5):1–4.

52. David A. Understanding the invention phase of management innovation: a design theory perspective. Eur Manag Rev. 2019;16:383–398. doi:10.1111/emre.12299

53. Aadland E, Cattani G, Ferriani S. Friends, gifts, and cliques: social proximity and recognition in peer-based tournament rituals. Acad Manag J. 2019;62(3):883–917. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.0437

54. Wen W, Yamashita A, Asama H. The influence of goals on sense of control. Conscious Cogn. 2015;37:83–90. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2015.08.012

55. Xiao J, Mao J-Y, Quan J, Qing T. Relationally charged: how and when workplace friendship facilitates employee interpersonal citizenship. Front Psychol. 2020;11:190.

56. Wu C-H, Parker SK. The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior: A perspective from attachment theory. J Manage. 2017;43(4):1025–1049.

57. Simons T, Friedman R, Liu LA, McLean Parks J. Racial differences in sensitivity to behavioral integrity: attitudinal consequences, in-group effects, and” trickle down” among black and non-black employees. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):650. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.650

58. Frese M, Kring W, Soose A, Zempel J. Personal initiative at work: differences between East and West Germany. Acad Manag J. 1996;39(1):37–63.

59. Nielsen IK, Jex SM, Adams GA. Development and validation of scores on a two-dimensional workplace friendship scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60(4):628–643. doi:10.1177/00131640021970655

60. Becker TE, Atinc G, Breaugh JA, Carlson KD, Edwards JR, Spector PE. Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(2):157–167. doi:10.1002/job.2053

61. Bernerth JB, Aguinis H. A critical review and best‐practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol. 2016;69(1):229–283. doi:10.1111/peps.12103

62. Fuller CM, Simmering MJ, Atinc G, Atinc Y, Babin BJ. Common methods variance detection in business research. J Bus Res. 2016;69(8):3192–3198. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

63. Sharif SMF, Naiding Y, Xu Y, Ur Rehman A. The effect of contract completeness on knowledge leakages in collaborative construction projects: a moderated mediation study. J Knowl Manag. 2020. doi:10.1108/JKM-04-2020-0322

64. Huang R-T, Yu C-L. Exploring the impact of self-management of learning and personal learning initiative on mobile language learning: a moderated mediation model. Australas J Educ Technol. 2019;35(3). doi:10.14742/ajet.4188

65. Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

66. Boğan E, Dedeoğlu BB. The effects of perceived behavioral integrity of supervisors on employee outcomes: Moderating effects of tenure. J Hosp Mark Manag. 2017;26(5):511–531.

67. Yan CH, Ni JJ, Chien YY, Lo CF. Does workplace friendship promote or hinder hotel employees’ work engagement? The role of role ambiguity. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2021;46:205–214. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.12.009

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.