Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 13

Why Women in Ethiopia Give Birth at Home? A Systematic Review of Literature

Authors Weldegiorgis SK , Feyisa M

Received 17 July 2021

Accepted for publication 12 October 2021

Published 9 November 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 1065—1079

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S326293

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Everett Magann

Seifu Kebede Weldegiorgis, Mulugeta Feyisa

Department of Midwifery, Salale University, Fiche, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Seifu Kebede Weldegiorgis Tel +251 912 461827

Email [email protected]

Objective: This study aimed at reviewing identifying reasons for home delivery preference, determining the status of homebirth in Ethiopia, and identifying socio-demographic factors predicting home delivery in Ethiopia.

Methods: A systematic literature review regarding the status of homebirth, reasons why women preferred homebirth and socio-demographic determinants of home deliveries was performed using CINAHL, MEDLINE, Google Scholar and Maternity and Infant Care. Keywords and phrases such as home birth, home delivery, childbirth, prevalence, determinants, predictors, women and Ethiopia were included in the search.

Results: A total of 10 studies were included in this review. The mean proportion of homebirth was 73.5%. Maternal age, ANC visits, maternal level of education, distance to facilities, and previous facility birth were significantly associated with homebirth. Perceived poor quality of service, distant location of facilities, homebirth as customary in the society and perceived normalness of labour were identified as reasons for choosing homebirth.

Conclusion: Despite the significance of skilled birth attendants in reducing maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, unattended homebirth remains high. By identifying and addressing socio-demographic enablers of home deliveries, maternal health service uptake can be improved.

Keywords: childbirth, homebirth, maternal health, facility birth

Introduction

Ethiopian institutional birth is one of the lowest in the world. According to the 2016 National Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey,1 only 29% birth occurred in health facilities.1 The remaining births are at home. However, since there is no care system that allows professionals to attend labour at home, homebirth in Ethiopia is unattended, unless by Traditional Birth Attendants.2 The lack of skilled attendance at birth is associated with the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity observed in Ethiopia.3 According to the World Health Organisation, in 2017 the maternal mortality rate was 401 per 100,000 live births, which although significantly reduced from 2010 levels (1030, per 100,000 live births), is still high compared with the global rate of 211 per 100,000 live births.3

There are several health policies and strategies in place, which aim at increasing the proportion of childbirth attended by skilled professionals such as midwives. In 2010, the most ambitious growth plan in the history of the country was announced—to be a middle-income country, as of 2020–2023.4 The plan was divided into two: Growth and Transformation Plan 1 (over a period of five years, 2010–2015), and Growth and Transformation Plan 2 (for the succeeding five years, 2015–2020). One of the objectives of the Growth and Transformation Plan 1 (GTP1) was to bring the proportion of births attended by skilled professionals to 60% by 2015. To do so, health professionals training institutions have been expanded, more than 38, 000 health extension workers have been deployed over the five-year period of GTP 1, and health centres and health posts were expanded to improve access to essential health care services including maternity health services.5 However, improving accessibility could not guarantee the effective utilisation of the service. Affordability was also a concern for consumers. As a result, to increase the uptake of service during childbirth, the government, with the help of foreign aid, made every service related to childbirth free, including C-section. To this day, any health care service related to pregnancy and childbirth is therefore free in Ethiopia.6

Despite those efforts, in Ethiopia, the proportion of women seeking care at a health facility during childbirth remains one of the lowest in the world. According to the latest Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey, only 29% of women gave birth at health facilities, while the rest 42%, 15% and 14% received support from TBAs, No One and Family or Friend, respectively.1 Moreover, the same survey also reported that four in five women did not attend health services for postnatal checks either. During their pregnancy, only 30% of women have had at least 4 antenatal visits—the minimum number of ANC visit recommended by the World Health Organisation.7 Despite an unsatisfactory response to the expansion of health care services, the successor of GTP1, GTP2, also focused on further expanding the health care service.

Strategies implemented so far have missed the fact that improving accessibility alone is not enough to increase service uptake. Exploring the perspective of those who choose home birth should be as important as health service expansion. Identifying crucial factors that play a significant role in the decision-making processes can provide an additional element of quality maternity service, the service that women want. This review focused on determining why women—despite health infrastructure expansion, health workforce boosts and a several awareness-creation campaigns about the importance of facility birth—prefer homebirth. It also attempts to identify demographic characteristics that affect women’s preference of place of birth.

Significance of Facility Birth in Ethiopia

According to the World Health Organisation, in 2017, globally, 810 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth.8 That is 295,000 maternal deaths in just one year. About 94% of these deaths occur in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Roughly, two-thirds of all maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan countries.9

About 75% of all maternal deaths are due to known and preventable causes, such as severe bleeding, infections (usually after childbirth), high blood pressure during pregnancy, complications from delivery, and unsafe abortion.10 All these causes can be prevented, detected early and managed if women can have access to skilled care before, during and after childbirth. This is what the developed countries have done to make maternal mortality a distant memory. For example, Liz Ford highlighted three elements of Britain’s maternal health success: 1) the establishment of its National Health Service to improve access to quality maternity service; 2) women empowerment in order to seek professional service during pregnancy and childbirth; 3) quality health professional education particularly midwifery education.11 This is to suggest that if poor countries like Ethiopia improve access to health services, then it is possible that they can reduce the unacceptably high maternal mortality. As a result, the Ethiopian government and international organisations are working toward improving accessibility of maternal health services. It has recorded a significant reduction in maternal mortality following the efforts to improve health service infrastructures.5 However, the service uptake is not satisfactory. Despite the increased number of health professionals, despite making the service charge-free, and regardless of significant improvement in health infrastructure, Ethiopia is still among the lowest facility birth. It is one of the countries with the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. Every year, about 22,000 women die in Ethiopia due to preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth.9

Unlike the developed world, in Ethiopia there is no system that provides home-based professional care during childbirth. Thus, in order to have optimal experience and outcome, women need to seek care from health care facilities. Otherwise, having unattended labour can put women and their babies at a higher risk of complications and negative birth outcomes.12 As explained above, government and international NGOs have implemented several strategies to encourage women to give birth at health facilities. Improving access to services through expanding health infrastructure and increasing number of health professionals is one of the focus areas. Moreover, creating awareness about the dangers of unattended labours, information on the impact of having an unskilled care provider, and the information on the importance of seeking care were provided to women and families using several media outlets.13 But the service uptake rate is still among the lowest in the world.1

What is Missing?

Strategies implemented by the government and other partners to improve maternal health in Ethiopia are making a difference. They, for sure, have improved the maternal and child health in the country. Over the last decade, for example, Ethiopia has significantly reduced its maternal and child mortality.3 These strategies directly contributed to the MMR reduction in the country. However, compared to the commitments and efforts, improvements are not satisfactory. The country has still got a long way to reduce preventable mortalities related to pregnancy and childbirth. To do so, it is important to assess the nature of strategies already in place.

Almost all plans are focused on improving access and/or quality of the service.14 As a result, women’s input or perspectives on the service have been neglected. Any strategy that does not include women’s—the direct participants, particularly when it comes to pregnancy and childbirth—input has less likelihood of achieving its objectives. There are many successful attempts in listening to women’s views. However, many of these attempts considered the attitude, opinions, and inputs of women who come to hospitals to give birth.15–17 But they mainly lack the perspectives of the majority of women—those women who preferred home birth. To improve facility birth utilisation, the target group should be those who chose to give birth at their home. It is very important to reach out to those women and try to determine their reasons and justifications. It is through this way that we can create hospital services that value women’s principles during childbirth. What is important for women during childbirth so that hospitals will attract women for childbirth? This is a crucial information that the current body of childbirth research is missing. This review attempted to close that missing insight.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

The review included articles:

- Published in peer-reviewed journals from 2010 and on ward

- That examined three outcome variables: homebirth proportion, determinants of homebirth preference, and reasons for choosing homebirth (regardless of other additional outcomes examined)

- Written in English

- Conducted in Ethiopia

Table 1 indicates inclusion criteria following a framework comprising population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS),18 giving examples of excluded articles. Moreover, a sample of articles excluded for the respective reasons is provided in Annex 1.

|

Table 1 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Articles Selected for This Review |

Information Sources

Four databases were searched during June 2020: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Maternity and Infant Care, and Google Scholar. Moreover, further articles were searched using one of the complementary searching techniques—Citation chaining.19 Backward searching—one of the types of citation chaining—is the technique used, where biographic lists of some selected articles were searched to locate additional articles. Mendeley was used as a database software to save and record search results. The software’s notification system was activated for the arrival of new articles after initial search was conducted.

Search Strategy

This review used a combination of coined terms encompassing different concepts. Factors associated with home birth and reasons for choosing home birth were searched using mainly two Boolean terms (“OR” and “AND”2). Terms under column A (Box 1) were combined using Boolean term “OR”, as well as terms under column B were combined with the same Boolean term.

Then, the resulting terms under column A were combined with terms under column B using a Boolean term “AND”. The search syntax is provided as Annex 2.

|

Box 1 Review Search Terms |

Study Selection

The first electronic database search yielded 1672 articles. The first step was to remove the duplicated articles. There was a “remove duplicates” tool on the Mendeley software, which was used to manage the database. Using this tool, duplicated search results were removed. This left 929 articles that entered the stage of screening for eligibility. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1), titles and abstracts were screened. Titles that were clearly out of the scope of this review were removed. Abstracts from the remaining articles were assessed for study eligibility. The form applied for screening and selection of studies is provided as Supplementary 1.

After screening the titles and abstracts for eligibility, 49 articles were acquired to enter the next stage—full-text screening to assess eligibility for the review. The full text of all articles were acquired and reviewed using the inclusion criteria: 1) quantitative studies; 2) reported outcome variables—mainly homebirth prevalence, determining factors of homebirth, and reasons to give birth at home; 3) Conducted on Ethiopian women 4) full text available (see Table 1). Almost all of the qualitative studies acquired addressed only the third objective of this review, missing the first two objectives. In contrast, quantitative studies conducted on the review topic addressed all three objectives, leading to the decision of qualitative studies to be excluded from this review. After reviewing the acquired full texts and assessing their eligibility against the criteria, 10 studies were included in this review. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the search and inclusion process. Examples of full articles excluded from the review are presented in Annex 1. And the sample inclusion and exclusion processes are provided as Supplementary 2 and Supplementary 3, respectively.

|

Figure 1 A flowchart diagram showing the selection process of included studies. Note: Adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.21 |

Data Items

The elaboration of variables that were used to answer the review question is presented in Box 2.

|

Box 2 Definition of Data Terms |

Quality Assessment

In terms of appraisal tools, we were not able to locate suitable appraisal tools for quantitative surveys. Therefore, we used a general tool that focused on common elements of research publications: clear description of methodology, presence of ethical approval process, specific objectives in line with the topic under study, result’s alignment with the intended objectives.20 Based on these points, we have categorized studies into high, average and low qualities. There were no excluded studies based on the appraisal, and there were no studies under the category of “low quality” (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Characteristics of Selected Studies |

Data Extraction

The steps and procedures used to identify the types of data to extract were as follows: 1) skim-read all selected studies to have the general idea of variables reported; 2) review the objectives of the review; 3) review the inclusion and exclusion protocols and; 4) read some published articles on the same area to further explore the data types needed to answer our review question. As a result, we identified descriptive data types such as study place and year, study design, study population and sample size. Regarding analytical data, we identified variables such as homebirth prevalence, predictors of homebirth, reasons for homebirth, women’s empowerment or autonomy, ANC visits and birth attendants at home.

After determining the data to be extracted, the next step was developing and piloting the Data Extraction Form (DEF). Piloting had two aims—to be familiar with the form and procedure, and to ensure all necessary data types are included.19 After applying the form on a couple of articles, there were no reduced variables (see Supplementary 4). However, we added one additional variable: “Presence of Birth attendant at home or not.”

After verifying the DEF, the next step was extracting data from the selected studies. We extracted descriptive data and analytical data (see Supplementary 5). During extraction, we used a highlighting technique to easily pick the data taken from the original articles, in case reviewing is required. To reduce extraction error or bias, besides conducting pilot on the DEF, we checked the actual data extraction twice. Doing data extraction for the second time after a few weeks of the first extraction can optimize the quality of data extraction and minimize errors.19 There were no major discrepancies in the two sets of data. We requested the authors of one of the selected studies,22 for further detail of their data collection and analysis method, which was not reported in detail. Following their response and clarifications, we have included the study for the review.

Data Analysis

The findings of this review have been presented as a narrative summary of the reviewed studies and therefore coded the data in themes related to key terms. A narrative summary involves a thematic or content analysis, which can be defined as a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting information in the form of themes within a text.23,24 Hence, in this review, factors that were significantly associated with women’s preference of homebirth were coded using key terms: “Socio-economic”, “Obstetric”, and “Infrastructure.” Moreover, findings related to women’s reasons to choose home delivery were coded using keywords such as: “The Beauty of Homebirth”, “Service Quality”, “Previous Experience” and “Societal”. These terms were refined several times as the coding progressed, and eventually the selected studies were recoded where necessary. Microsoft Excel was used for data extraction, coding and data management.

Findings

Study Selection

Electronic searches identified 1672 citations, which once duplicate was removed left 929 unique citations to be screened for inclusion. Their titles and abstracts were assessed for their relevance to the review, resulting in 49 potential citations being retained. Then, the full texts of all citations were obtained. After applying the inclusion criteria to full-text papers, 39 citations were excluded for reasons, such as not reporting outcome variables, out-of-Ethiopia study, focused on antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care services. As such, ten citations were included in the review (Figure 1). The following synthesis, therefore, is based on those selected ten studies. The synthesis follows a sequence of titles: Description of Selected Studies; Prevalence of homebirth; Factors associated with homebirth; Reasons to Give Birth at Home.

Description of Selected Studies

A total of 10 studies were selected, published 2013–2019. Table 2 summarizes further details of the characteristics of selected studies. Four studies were originated from Amhara state,16,22,25,26 three were conducted at the national level,27–29 two from Tigray state,30,31 and one from Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ (SNNP) state.15 Research designs included 7 cross-sectional studies, one case-control, one follow-up, and one comparative study.

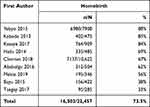

Prevalence of Homebirth

Only one study did not report the prevalence of homebirth.28 The mean proportion of homebirth in this review was 73.5%, ranging from 25%25 to 88.3%.29 In the majority of selected studies, the prevalence of homebirth was higher than 50% (Table 3).

|

Table 3 The Reported Proportion of Homebirth in the Selected Studies |

Half of selected studies in this review reported the status of women’s autonomy in terms of preference of place of delivery. The majority of respondents in these studies reported that women have been empowered to independently decide their preferred place of delivery. Five studies reported women’s participation in making decision regarding place of delivery. More than 74% of women in three studies reported that they independently decided on their preferred place.16,25,29

Determinants of Homebirth

Table 4 summarizes independent variables associated with women’s preference of home as a place of delivery.

|

Table 4 Demographic Characteristics Associated with Homebirth |

Parity, ANC Visits, Maternal Age

Multiparous women preferred homebirth over primiparous.15,26,29 On the other hand, this review found that ANC visits predicted facility birth, given women have had at least four visits during their entire pregnancy. Those who have had just one visit were more likely to give birth at home.16,22,26,29,31 Regarding maternal age, the review found that older women preferred homebirth over their counterparts.15,16,27

Residence and Access to Mass Media

Two studies reported the significance of residency. Rural residency positively affected homebirth, while women living in urban areas preferred facility birth.28,29 Access to media has a statistical significance in affecting women’s preference of place of birth. In three studies, women who had access to media preferred facility birth to homebirth.27,29,31

Level of Education

Women’s level of education was one of the most frequently reported determinants in selected studies. Six studies reported its significance, and found that educated women were more likely to give birth at facilities than their counterparts.15,16,25,27,29,30

Distance to Facilities

The second most frequently reported factor that affected women’s decision of place of delivery was distance from health facilities. Five studies reported that women who lived far from health facilities were more likely to give birth at home than those who lived closer to health facilities.22,26,29–31

Previous Facility Birth

Three studies attempted to explore the effect of previous facility birth on mother’s preference of place of delivery for the current pregnancy. Two of those studies found that women with previous facility birth chose home for their current pregnancy. Ababulgu and Bekuma15 found that women who have a history of hospital birth are less likely to give birth at facilities again (AOR=0.24 and 95% CI = 0.11, 0.52). In another study, previous use of facilities for childbirth has reduced re-attendance for the next pregnancy by 45%.26 In contrast, one study found that previous institutional delivery was significantly associated with preference for facility delivery.22

Women Empowerment

Women’s involvement in decision-making process regarding place of delivery is significantly associated with the preference. Hailu and Berhe30 found that independent women tend to prefer facility birth than those who do not. Moreover, socio-economic status has significantly affected women’s preference of place of delivery. Women who are among higher socio-economic status are more likely to give birth at hospitals than those from poor economic status.27,29

Reasons for Homebirth Preference

Selected studies explored possible reasons provided by participants for deciding to give birth at home. Eight studies have reported participants’ reasons to give birth at home (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Reasons to Give Birth at Home |

Poor Quality of Service

Concerns about the quality of maternity health services provided in health institutions were one of the frequently reported reasons for giving birth at home. Poor service is explained in selected studies including bad approaches of health professionals and the issue of privacy during delivery. Bayu et al16 found that 28% of study participants chose home because of the “unwelcoming approach” of health professionals. About half of women who gave birth at home in one study stated that “disliking facilities” is one of the reasons for their homebirth preference.30 About 12.8% of participants reported that health professionals’ approach is “unfriendly” and that made them chose homebirth.22

Reasons Related to Distance and Transport

Four studies reported distance-related reasons for choosing home birth over a facility-based birth. Mekie and Taklual22 found that transport accessibility and distance from facilities were the reasons for 28.1% and 26% of respondents, respectively. The analysis of national health survey data has found that 14% of women who deliver at home stated that too far from facilities as a reason for homebirth.28 About 13% of participants in another study reported that the transport cost is unaffordable to get to health facilities.15 Moreover, Kebede et al26 found that too far to get to facilities was a reason for 12% study participants who have had a preference for homebirth.

Home Birth is Customary

In some studies, home birth has been found to be a social norm and customary. Yaya et al28 found that for 29% of participants, homebirth is just a customary practice that they do not need to go to facilities. Moreover, in another study, for 27.6% of study participants, homebirth is customary.25 A follow-up study selected in this review also found homebirth to be a customary practice. In other study, 31% of homebirths are due to customary reasons.16

The “Beauty” of Homebirth

In the selected studies, the uninviting approach of health professionals has not been the only reason to prefer homebirth. It is also because home has been perceived to be better than hospital birth. The presence of family support, familiarity of the place, freedom and privacy were among the attributes of preference for home. About 36% of homebirth in one study were due to the family support at home.25 In other study, 30.4% of participants said that “home is more comfortable than hospitals”,30 and this reason was true in 24% of homebirths in other studies.16 Kebede et al26 found that 35% of respondents believed that homebirth provides the needed family support, and 21% believed home maintain privacy at optimum level.

Normality of the Childbirth

Conditions such as normality of childbirth and the nature of how labor started were among the reasons for homebirth. Women chose homebirth because the condition was “normal.”16 More than half of women who gave birth at home in one study stated that everything was normal and there was no reason to seek professional care.28 About 77% of homebirths in another study stated their reasons for homebirth as: “labor was normal.”25 Besides the perceived normality of childbirth, the way labor started has also been mentioned as the reason for homebirth. In three studies, respondents stated that labor started incidentally, and the process was too short and too fast to go to health facilities.16,22,25

Discussion

This review examined the status of homebirth in Ethiopia by determining demographic characteristics, which are significantly associated with respondents’ preferred place for delivery. Moreover, the review attempted to explore women’s reasons to prefer home as their choice of place to give birth to their babies.

Limited studies in this area make this review unique in its way. If maternal health service must improve in the country, an understanding of women’s opinion is vital. Conena32 outlined that the data we have access to regarding maternal and child health lack women’s opinion. Without considering women’s say on their own health issues, the implementation of any strategy to improve women’s health becomes significantly difficult. This review tried to consider women’s say about childbirth services, particularly those who are not using the service provided.

In addition, one of the objectives of this review was to determine the prevalence of homebirth. This review identified an average homebirth prevalence of 74%. This suggests that giving birth at home is a commonplace practice among study participants (Refer Table 2). This is consistent with findings of Ethiopian National Health Survey,1 in which the national homebirth prevalence is 72%. The similarity might be due to both the survey and this review were on the national level, considering various demographic areas within the country.

Determinants of Homebirth

In the four studies selected in this review, women who perceived their pregnancy as “normal and without any problem” did not seek for a skilled birth attendant during labour and delivery.16,22,25,28 The finding is similar to other studies where the perceived normality of pregnancy prevented women from attending facilities during labour.17 This suggests that there is an important opinion among women that can be described: facility births are for abnormal and complicated pregnancy and childbirth.

As we discussed above, in our review, lower education was one of the strong predictors of homebirth. Greater education alongside higher socio-economic status is significantly related to facility birth. One systematic review conducted in sub-Saharan countries reported a similar finding.33 Another study conducted to examine a relationship between women’s economic independence and their health-seeking behavior reported that women with higher educational level (hence independent women) are 4 times more likely to seek health care service, particularly during pregnancy and childbirth, than their counterparts.34 In contrast, studies in developed countries reported contradicting findings. For example, a meta-analysis conducted in Australia to compare childbirth outcome with women’s place of birth reported that women with advanced education chose home over facilities to give birth.35 The difference between educated women in developing and developed countries in terms of place of delivery can be explained by the movement of normalizing childbirth in the latter countries. The concept of physiologic childbirth is very immature in developing countries, medically advanced childbirth is still considered as good practice. We could not find studies on physiologic childbirth focused on developing countries which, by itself, can be an evidence of how new the concept is in those nations. Regarding developed countries, the efforts to change the misconception about childbirth as a condition that requires immediate and continuous medical interventions is strong.36–38 Even the World Health Organization is calling, through its intrapartum care guideline, for de-medicalization of childbirth unless there are medically proven indicators.8

In recent years, several studies are questioning the benefit of secondary and tertiary institutions as an optimum place for labour and delivery. For example, a study conducted in New Zealand reported that women who gave birth at tertiary institutions are at a higher risk of unnecessary intrapartum interventions such as assisted birth and caesarean delivery than those who have had homebirth.39 This suggests that medicalising birth may have an adverse effect on the labour process and its outcome than we might think. The movement is already taking a shape that women are seeing childbirth as normal—not a disease condition—that they are starting to prefer homebirth to facility births. This difference is evidently showing discrepancy of women’s preference of place of birth between developing and developed countries. That is why higher education predicts homebirth in western nations, while it is a common factor significantly associated with women’s preference of facility-based childbirth in third-world countries like Ethiopia.

In most studies selected for this review, ANC attendance was identified as one of the most common variables associated with facility-based childbirth. A systematic review aimed at determining the effect of antenatal care attendance on women’s preference of place of delivery in Ethiopia found a similar relationship between ANC attendance and hospital birth.40 This might be because of the health education during ANC that has been designed to inform women about the importance of facility birth in preventing adverse childbirth outcomes, and to timely manage in case the process gets complicated. Similarly, a case–control study conducted in Ethiopian state of Oromia reported that ANC attendance during pregnancy was a strong predictor of facility-based childbirth.41 However, the finding contradicts with the study conducted by Bohren et al, where women’s ANC attendance during pregnancy reduced their likely of giving birth at health institutions. The study highlighted that women thought attending ANC prevents problems related to pregnancy and childbirth that they do not need to seek out skilled birth attendants during labour and delivery.17

In this review, higher parity is one of the strong determinants of homebirth. This can be explained by the fact that fear of childbirth and eagerness to seek help in order to feel “safe” reduced as a woman becomes more experienced with pregnancy and childbirth. Multiparous, based on their previous facility birth experience, might also decide not to come to facility services. For example, in a recent qualitative study on women’s experience of facility-based childbirth in Ethiopia, women reported that they suffered more from disrespectful and abusive care than the labour pain itself.42 This can explain why multiparous women are not coming to facilities again. Similarly, a study conducted in Nigeria found that the odds of giving birth at home was 2.7 times higher in multiparous than those who were having their first babies.43

The health service coverage in Ethiopia favors urban areas, leaving most (more than 85% of population lives in rural areas) of the country behind34 This has also been identified in our review. Residency was one of the significant factors associated with women’s preference of place of birth; rural women were more likely to give birth at home than their urban counterparts. This can be explained by the physical distance of health facilities in rural areas. Moreover, access to media has played a significant role in encouraging urban women to give birth with the attendance of skilled professionals in health facilities. In most of the selected studies for this review, the physical distance of health facilities has been found to be one of the significant determinants of the place of deliveries. Those who are living 2 or more hours away from the facilities are more likely to give birth at home than those living closer. Several studies also found that distance from health facilities could independently affect women’s preference of place of delivery favoring homebirth.17,41,44 Naturally, it is expected to see a high prevalence of homebirth where facilities are located remotely. This can explain why rural areas record significantly higher homebirth rates compared to urban areas—of course, in addition to other factors.

Surprisingly, our review identified a significant association between previous facility-based childbirth and homebirth. In other words, those women who gave birth in hospitals previously are not coming again for their next pregnancies. This might be due to the rising problem related to sub-optimal maternity services, such as disrespectful approach of the health care providers. Studies report that the probability of having unpleasant experience during childbirth is significantly higher than having satisfactory experience; women felt “abusive approach was more painful than the labour itself.”42 Another explanation could be that women are becoming more aware of and concerned with unnecessary but common interventions in hospitals, which could lead them to the decision to stay at home.45 Our finding is also similar to a study conducted in Ethiopia to determine why women do prefer homebirth.46 According to this study, previous facility-based birth was significantly associated with homebirth that poor qualities in facilities were main attributes to not going again. A study conducted in Senegal similarly found that previous institutional birth was associated with homebirth of the consecutive pregnancy, highlighting poor quality and male care providers as the major elements of the unpleasant experience.47 Similarly, Jouhki M-R,48 reported that previous hospital birth experience has led women in Finland to prefer homebirth over their current pregnancy.

Regarding women empowerment in the household, our review found that the uptake of services provided by skilled birth attendants is significantly higher among empowered and independent women than those whose voices and concerns are not heard well in the household. Those who were autonomously making decisions and those who were active participants in the decision-making process preferred health institutions to give birth. A study that explored women’s autonomy from the perspective of economic independence reported similar findings that women’s autonomy in the household predicted higher uptake of maternity health services, such as family planning, antenatal care, and skilled birth attendants during labour and delivery.34 A study conducted in Pakistan found that women’s decision-making power has a significant correlation with the uptake of maternal health services including facility-based birth.49 Ahmed et al50 analyzed a Demographic and Health Surveys of 31 developing countries to determine the relationship between women’s economic, educational and empowerment status and their maternal health service utilization. The analysis concluded that women with the highest empowerment scores were twice as likely as those with null empowerment scores to attend antenatal care services and the presence of skilled attendants at birth. This suggests that to accelerate the uptake of health service that has significant impact in reducing maternal and child mortality in developing countries, it is necessary to attend to parallel investments that aim at empowering women through access to education and economic independence. Moreover, Pratley,51 after systematically reviewing evidence from the developing world to determine the association between women’s empowerment and maternal health service uptake, concluded that improving women’s empowerment is a viable strategy to increase health service uptake.

Reasons for Homebirth

In this review, women have reported several reasons for giving birth at home. The perceived comfort of birthing at home was one of the reasons for preferring home births. The finding is broadly in consistent with a study conducted in the United Kingdom,20 in which respondents reported that “home-like” environment is more important than the “clinical appearances” of most health facilities. Another study conducted in Finland also reported that the convenience of the environment at home was one of the major reasons to give birth at home.48 It is understandable to perceive home as a more comfortable environment than hospitals, after all home is home. However, it is important to note, in case of developing countries like Ethiopia, that no matter how comfortable women think home is, since there are no home midwives, giving birth at home is totally unattended (or attended by traditional birth attendants), which could be dangerous.

In this review of selected studies, poor quality of services was one of the reasons women decided to choose homebirth. Several studies have reported poor qualities at health institutions as barriers to service utilization.17,45,47,48 This can explain why homebirth is higher in the rural area. As we have discussed elsewhere, health facilities in the rural and urban areas of Ethiopia are highly unbalanced. Therefore, a woman living in urban area might have a chance of changing facilities for the next pregnancy. However, this is not the case for rural women because facilities are rarely accessed, and if the quality is poor, they are likely to stay home—to find alternative facility is unthinkable. Therefore, as we are working to improve accessibility, it is vital to work on the quality of facilities—with much attention to the rural areas because it is vital to make sure that women will come whenever they are pregnant, not just once.

Another reason for choosing home as a place for delivery is the perceived normality of pregnancy. In this review, perceived normality of pregnancy and childbirth was identified as one of the reasons women chose homebirth. Studies from Ethiopia and other developing countries have reported similar findings.17,41 In other words, women seek professional services if and only if they think, or have been told, that their pregnancy is abnormal pregnancy with underlying medical or obstetrical problems.

Looking at homebirth as a customary practice in the society was another common reason mentioned by respondents for their birth experience to happen in their home. Women do not go to hospitals to give birth because no one is seeking for professional service in their society. The social significance of facility birth is very less. A comparative study between Ethiopia and Nigeria also reported that in both countries, a significant proportion of study participants reported that homebirth is customary.28 An analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey data also reported that the notion of homebirth as customary was one of the most common reasons women have had for homebirth.29 Despite the efforts to make facility-based childbirth customary in Ethiopia, ours and other related reviews found that, in some communities, homebirth is customary and has societal significance.

Conclusion

The prevalence of homebirth in this review is very high. Several socio-economic and demographic factors are keeping women from seeking professional care during pregnancy and childbirth. In our review, we have identified several factors significantly associated with homebirth in Ethiopia: parity, women’s level of education, distance to facilities, resident, previous facility-birth experience, and women’s empowerment and/or autonomy in the household were among demographic factors, which were significantly associated with homebirth in Ethiopia. Regarding reasons to choose homebirth, the review found some frequently mentioned reasons such as “previous bad experience at facilities”, “the pregnancy was normal”, “homebirth is customary”, “home is more private and/or comfortable than facilities”, and “distance from facilities.” Based on the findings of this review, empowering women can improve their tendency toward seeking health care service during pregnancy and childbirth, which will in turn reduce homebirth significantly. Women’s access to education improves not only their economic situation but also that they will be motivated to seek care during one of the most important events in their life—pregnancy and childbirth.

Surprisingly, previous facility birth was one of the enabling factors for homebirth in this review. This finding implies that care providers’ approach and attitude toward laboring mothers determine not only the outcome of current pregnancy (not the only determinant but plays significant role) but also the decision that same woman will take for her next child’s place of birth. To improve facility birth prevalence, as it appears to be the safest place to give birth in Ethiopia, then it is health care providers’ responsibility to provide women with friendly, respectful and compassionate care for those who already came to facilities. Another implication of the findings of the review is that there is a significant community perception toward the necessity of seeking care during childbirth. It has been repeatedly reported that women do not seek care for childbirth, which they perceived to be normal. In other words, they only go to health facilities when they face problems during labour. Using ANC sessions as an opportunity, health providers can clarify these myths.

Recommendation

Ethiopia is a country with one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. Providing access to quality maternal health services is one of the essential strategies to reduce most of the deaths attributed to preventable causes. Over the last two decades, there has been a relatively significant reduction in the number of women dying due to childbirth complications. The government's commitment alongside the support of various partners is attributable to the reduction of maternal mortality. Despite efforts to improve access to health care in Ethiopia, the number of women seeking care during pregnancy and childbirth is still very low. It is crucial to determine why women are not seeking care. This review attempted to determine the prevalence of homebirth, the demographic characteristics that are significantly associated with homebirth, and reasons why women in Ethiopia are giving birth at home. Based on its outcome described under the Findings and Discussions, this review generated and discussed some of the important recommendations below.

The review identified that empowering women through access to education and employability can significantly accelerate their maternal health service uptake, which in turn plays a crucial role in reducing maternal mortality in Ethiopia. A 2000–2016 trend study on maternal health service utilization inequality also recommended that if we have to improve service utilization, then there must be a strategy, which targets poor and illiterate women to empower them so that they will be informed and empowered enough to seek care during childbirth.52

This review identified a misconception that facility birth is for abnormal pregnancy and childbirth. This misconception can be addressed during ANC visits by adding the issue to the topics facilities cover under ANC education sessions. Health care providers should also give emphasis on multiparous women during ANC service, as these women are more likely to give birth at home than their counterparts. Women who gave birth at facilities are not coming again for the next pregnancy. Previous facility birth is positively associated with homebirth. In other words, facilities, with their poor-quality services and abusive attitude of their employees, are forcing women to choose homebirth. Hence, by improving service quality and professionals’ competency, it is possible to improve the uptake of maternal health services in Ethiopia. One study from Kenya reported that by adhering provision of care to the required standard maternal health service uptake increased from less than 40% to 80–100% within three to six months.53

We suggest that it is important to improve the inequalities between rural and urban women regarding access to health care services, which is contributing to the higher prevalence of unattended birth among rural women. From rural women perspectives, it is understandable that they could not get to the facilities on time as those facilities are at an unreachable distance. Government’s effort of building maternity waiting homes so that rural women approaching their due dates will stay until childbirth is bringing a difference in the improving proportion of facility births in Ethiopia.54 However, alongside building health facilities in remote areas, those maternity waiting homes can be seen as effective and immediate interventions, and they should be further expanded into other areas. Further study should be conducted to find out the socio-demographic determinants of homebirth in Ethiopia.

Author Contributions

Both authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all three areas: took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. EDHS. Demographic and Health Survey 2016 Addis Ababa; Meryland: Central Statistical Agency; The DHS Program; 2017.

2. Roro M, Hassen E, Lemma A, Gebreyesus S, Afewerk M. Why do women not deliver in health facilities: a qualitative study of the community perspectives in south central Ethiopia? BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:556. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-556

3. World Health Organisation. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000-2017.Geneva, WHO;2018

4. Growth and Transformation Plan I. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Finance and Economic Development; 2010.

5. Growth and Transformation Plan 2. Addis Ababa: National Commission Plan; 2016.

6. Pearson L, Gandhi M, Admasu K, Keyes E. User fees and maternity services in Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(3):310–315. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.007

7. WHO. Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience; 2016.

8. WHO. Recommendation: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2018.

9. World Health Organisation. Maternal Mortality. Key Facts. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Accessed October 26, 2021.

10. Mekonnen W, Gebremariam A. Causes of maternal death in Ethiopia between 1990 and 2016: systematic review with meta-analysis. Afr J Online. 2018;32(4). Available from: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/60503. Accessed October 26, 2021.

11. Ford L. Why Do Women Still Die Giving Birth? London: The Gurdian; 2018.

12. Lindtjørn B, Mitike D, Zidda Z, Yay Y. Reducing stillbirths in Ethiopia: results of an intervention programme. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197708. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197708

13. Shifraw T, Berhane Y, Gulema H, Kendall T, Austin A. A qualitative study on factors that influence women’s choice of delivery in health facilities in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1). doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1105-7

14. Bernt L, Demissew M, Zillo Z, Yaliso Y. Reducing maternal deaths in Ethiopia: results of an intervention programme in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169304.

15. Ababulgu FA, Bekuma TT. Delivery site preferences and associated factors among married women of child bearing age in Bench Maji Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2016;26(1):45–54. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v26i1.9

16. Bayu H, Adefris M, Amano A, Abuhay M. Pregnant women’s preference and factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Debra Markos Town, North West Ethiopia: a community based follow up study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0437-z

17. Bohren M, Hunter E, Munte-Kass H, Souza P, Vogel J. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based deliveries in low-and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1). doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-71

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRSIMA statement. Plos Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

19. Dundar Y, Fleeman N. Developing my research search strategy. In: Boland A, Cheery MG, Dickson R, editors. Doing a Systematic Review: As Student’s Guide. london: SAGE Publications; 2017:62–78.

20. Hollowell J, Li Y, Malouf R, Buchanan J. Women’s birth place preferences in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the quantitative literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–17.

21. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372–n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

22. Mekie M, Taklual W. Delivery place preference and its associated factors among women who deliver in the last 12 months in Simada district of Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):114. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4158-7

23. Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2019;104:333–339. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

24. Bruan V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2008;3(2):77–101.

25. Kasaye HK, Endale ZM, Gudayu TW, Desta MS. Home delivery among antenatal care booked women in their last pregnancy and associated factors: community-based cross sectional study in Debremarkos town, North West Ethiopia, January 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):225. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1409-2

26. Kebede B, Gebeyehu A, Andargie G. Use of previous maternal health services has a limited role in reattendance for skilled institutional delivery: cross-sectional survey in Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:79. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S40335

27. Chernet AG, Dumga KT, Cherie KT. Home delivery practices and associated factors in Ethiopia. J Reprod Infertil. 2018;20(2):102–108.

28. Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Uthman OA, Amouzou A. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a comparative study between Ethiopia and Nigeria. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196896. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196896

29 Yebyo H, Alemayehu M, Kahsay A. Why do women deliver at home? Multilevel modeling of Ethiopian national demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124718. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124718

30. Hailu D, Berhe H. Determinants of institutional childbirth service utilisation among women of childbearing age in urban and rural areas of Tsegedie district, Ethiopia. Midwifery. 2014;30(11):1109–1117. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.009

31. Tsegay R, Aregay A, Kidanu K, Alemayehu M, Yohannes G. Determinant factors of home delivery among women in Northern Ethiopia: a case control study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):289. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4159-1

32. Conena C. Redefining the challenge of maternal mortality in contemporary MCH: a seminar with Dr. Gene Declercq; 2019.

33. Moyer C, Mustafa E. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1). doi:10.1186/1742-4755-10-40

34. Woldemicael G, Tenkorang EY. Women’s Autonomy and Maternal Health-Seeking Behavior in Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:988–998. doi:10.1007/s10995-009-0535-5

35. Scarf V, Rossier C, Vedam S, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery. 2018;62:240–255. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.024

36. Thompson SM, Nieuwenhuijze MJ, Low LK, De Vries R. Creating guardians of physiologic birth: the development of an educational initiative for student Midwives in the Netherlands. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(5):641–648. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12999

37. Kennedy HP, Cheyney M, Lawlor M, Myers S, Schuiling K, Tanner T. The development of a consensus statement on normal physiologic birth: a Modified Delphi Study. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(2):140–145. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12254

38. Davis-Floyd R, Barclay L, Davis B-A, Tritten J. Birth Model That Work. London: University of Calefornia Press; 2009.

39. Davis D, Baddock S, Pairman S, et al. Planned place of birth in New Zealand: does it affect mode of birth and intervention rates among low-risk women? Birth. 2011;38(2):111–119. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00458.x

40. Fekadu G, Kassa G, Berhe A, Muche A, Katiso N. The effect of antenatal care on use of institutional delivery service and postnatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3370-9

41. Ejeta E, Nigusse T. Determinants of skilled institutional delivery service utilization among women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Bako District, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012/13 (Case-Control Study Design). J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;3(2):36–42. doi:10.11648/j.jgo.20150302.14

42. Welday M, Worku A, Medhaniye A, Edin K. Women suffer more from disrespectful and abusive care than from the labour pain itself: a qualitative study from Women’s perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–6.

43. Ashimi A, Amole T. Prevalence, reasons and predictors for home births among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Birnin Kudu, North-west Nigeria. Sexual Reprod Healthcare. 2015;6(3):119–125. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2015.01.004

44. Simkhada B, Teijlingen E, Porter M, Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2007;61(3):244–260. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x

45. Boucher D, Bennet C, McFarin B, Freeze R. Staying home to give birth; Why women in the United States choose home birth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(2):119–126. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.09.006

46. Shiferaw S, Spigt M, Tekie M. Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):1.

47. Faye A, Niane M, Ba I. Homebirth in women who have given birth at least once in a health facility: contributory factors in a developing country. Scand J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;90(11):1239–1243.

48. Jouhki M-R. Choosing homebirth: the women’s perspective. Women Birth. 2011;25:56–61. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2011.10.002

49. Hou X, Ma N. The effect of women’s decision-making power on maternal health services uptake: evidence from Pakistan. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28(2):176–184. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs042

50. Ahmed S, Creanga A, Gillespie D, Economic Status TA. Education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilisation in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011190

51. Pratley P. Associations between quantitative measures of women’s empowerment and access to care and health status for mothers and their children: a systematic review of evidence from the developing world. Soc Sci Med. 2016;169:119–131. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.001

52. Gebre E, Worku A, Bukola F. Inequities in maternal health services utilization in Ethiopia 2000–2016: magnitude, trends, and determinants. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0556-x

53. Mwaniki MK, Vaid S, Chome IM, Amolo D, Tawfik Y. Improving service uptake and quality of care of integrated maternal health services: the Kenya Kwale district improvement collaborative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–9.

54. Tiruneh GT, Getu YN, Abdukie MA, Eba GG, Keyes E, Bailey PE. Distribution of maternity waiting homes and their correlation with perinatal mortality and direct obstetric complication rates in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.