Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 16

Vaccine Cold Chain Management and Associated Factors in Public Health Facilities and District Health Offices of Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia

Authors Erassa TE, Bachore BB, Faltamo WF , Molla S, Bogino EA

Received 23 August 2022

Accepted for publication 29 December 2022

Published 12 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 75—84

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S385466

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Tsegaye Eka Erassa,1 Behailu Balcha Bachore,2 Wolde Facha Faltamo,3 Simegn Molla,2 Efa Ambaw Bogino4

1Maternal, Neonatal, Child Helath and Nutrition Directorate, Wolaita Zone Health Department, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia; 2School of Public Health, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia; 3Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia; 4Department of Dermatovenereology, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Efa Ambaw Bogino, Email [email protected]

Background: Vaccines are medical products with a short shelf life and are easily damaged by deviations in temperature from the recommended ranges. Vaccines lose their quality if the cold chain system is not properly managed. Cold chain management is still a major challenge in developing countries, including Ethiopia. Thus, this study aimed to assess vaccine cold chain management and associated factors at public health facilities and district health offices.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study design was applied from March 1– 28, 2021. One hundred and thirty-six health institutions were selected by simple random sampling method. Data was collected using the observation check list and interviewer-administered pre-tested structured questionnaires. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 25. The binary logistic regression was employed and those variables with a p-value less than 0.25 in the bivariate analysis were used for multivariable logistic regression. Then multivariate analysis at a p-value < 0.05 and AOR with 95% CI was used to measure the degree of association between independent variables and the outcome variable.

Results: The study indicates that 83 (61%) public health facilities had good cold chain management practice at 95% CI (52.2– 68.4). Experience greater than 2 years (AOR=2.8, 95% CI=1.13– 6.74), good knowledge on cold chain management (AOR=3.02, 95% CI=1.2– 7.4), training on cold chain management (AOR=1.86, 95% CI=1.36– 9.84), and supportive supervision on cold chain management (AOR=2.71, 95% CI=1.1– 7.14) were statistically significantly associated with good cold chain management practice.

Conclusion: The result of the study indicated that there was low cold chain management practice in the study area. Strengthening the knowledge of healthcare workers and supportive supervision on cold chain management by giving training and monitoring their practice toward cold chain management may help to improve the cold chain management practice.

Keywords: cold chain, vaccine, cold chain management, Ethiopia

Introduction

Globally the high impact of vaccine-preventable diseases has been averted by introducing immunization, which saves two to three million lives per year and it was recognized as a powerful public health intervention.1,2 In Ethiopia, the Expanded Program on Immunization started in 1980 to decrease the mortality and morbidity of children and mothers from vaccine-preventable diseases.3

Globally 29% of under-five mortalities were due to poor vaccine cold chain management and poor immunization uptake in developing countries but, nowadays, many countries of the world enforce and achieve a high coverage of required vaccinations for every resident, making efforts to eliminate constraints to vaccination among vulnerable classes, but problems still remain in the vaccine storage and handling.4

The cold chain system is assumed to be at greatest risk, particularly in developing countries where a power supply is unreliable and facilities for its maintenance are not well developed.5 Studies have also reported that improper vaccine storage leading to the administration of sub-potent vaccines may have been associated with outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in several developing countries.5,6 Maintaining the cold chain is the main duty of producers, distributors, public health staff, and health care providers.7

In Ethiopia, vaccine-preventable diseases are substantially contributing to under-five mortality.8 The main problem in Ethiopia has been vaccines losing their potency during storage at the center, even if they were potent on arrival, which enhances the chances of several outbreaks from different parts of Ethiopia.9 In addition according to reports from several findings in Ethiopia, the majority of facilities in Ethiopia have registered poor vaccine management practices and factors like EPI-related training, work experiences, and knowledge of cold chain management were reported as factors related to cold chain management practices.10–12

The major challenges of vaccination programs are associated with the vaccine cold chain management and cold storage facilities, thus vaccine cold chain management practice would be the backbone of successful immunization programs.13 So, the aim of this study was to assess the vaccine cold chain management and associated factors at public health facilities and the district health office of Wolaita zone, Ethiopia and contributing factors to the paradox between high vaccination coverage rates and the appearance of vaccine preventable disease.

Methods

Study Setting

The study area was the public health facilities of Wolaita Zone. Wolaita zone is located 360 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city. The authors select this area because it is a densely populated area in the southern region of Ethiopia. In addition, in some of the health facilities in the Wolaita zone providing EPI service is challenging since it is found in very remote areas where there is no access to transport service.14

Study Design and Period

A facility-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from March 1–28, 2021.

Source Population

All assigned health workers at the EPI unit in public health facilities of Wolaita Zone were the source population.

Study Population

Assigned health workers in the EPI unit who were found in randomly selected public healthcare facilities were included as the study population.

Exclusion Criteria

Health workers at public health facilities whose EPI unit was closed after three visits at the time of data collection were excluded.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

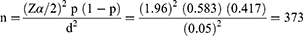

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula for a cross-sectional study using the following formula.15

where:

• Z=level of confidence (95% CI=1.96);

• P=proportion of baseline level of the indicators, which is 58.3% (15/14); and

d=margin of error (5%).

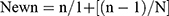

Where there is a predetermined population, in this case, there were 212 facilities in Wolaita Zone. Then the sample size generated from the above equation needs to be multiplied by the Finite Population Correction (FPC) factor (N<10,000). For our purpose, the formula can be expressed as:  .

.

where:

New n=the adjusted new sample size;

N=the population size=212; and

n=the sample size (373) obtained from the general formula using the example above, ensuring a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level would require:

n = = 373/ 2.75 = 136

Contingency (for non-response and incompleteness=10%).

The total sample size from the sample proportion is 150.

First, we stratified by type of healthcare facility into hospitals, health centers, and Woreda health office. Afterward, the sampling frame was prepared using a list of health facilities obtained from the zonal health department. Then from the 212 health facilities (Hospitals, health centers, health post and health offices) with refrigerators in Wolaita Zone, 150 health institutions were selected by simple random sampling. Then sample size was allocated proportionally to the total health facilities in the zone. From the selected health facilities, four were hospitals, 47 were health centers, 83 health posts, and 16 district (woreda/town) health offices were selected randomly. The schematic presentation of sampling procedure to select health institutions and study participants are shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Schematic presentation of sampling procedure to select health institutions from Wolaita zone public health facilities, 2021. |

Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

A modified questionnaire from the Federal Minister of Health (FMOH) on cold chain monitoring indicators was used to collect data.16 The questionnaire consists of six main parts, mainly: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, availability of cold chain equipment, states of infrastructure, attitude towards cold chain management practices, knowledge towards cold chain management practices, and cold chain management practice. The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated into local language and finally to English. The questionnaire was also tested for internal consistency (reliability) by Cronbach’s Alpha test. Data was collected by interviewing assigned responsible persons at Woreda health offices, Hospitals, health centers, and health posts. At the same time observations were done simultaneously during interview. During observation, temperature monitoring charts, VVM states, ledger books for vaccine balance, and vaccine arrangement in the refrigerator were observed.

Data Quality Assurance and Analysis

Data quality was assured by pretesting on six health centers out of the study area. Two data collectors and one supervisor who were working as EPI coordinators in other Health centers were selected and trained for data collection. The data collectors and supervisor were trained health professionals who had taken EPI training. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical review committee of the Wolaita Sodo University (Ref. No 41764/2021). The study did not expose participants to unnecessary risk as a result of interviewing and also written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the interview.

Data were collected by open data kit (ODK) and exported into SPSS version 25 for analysis. After cleaning data for inconsistencies and missing value in SPSS, descriptive statistics such as mean, SD, and frequency was done. The necessary assumption of logistic regression was checked using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit-test to assess the fitness of the model (p-value=0.184). Multicollinearity was checked using a cut-off point based on the variance inflation factor (VIF) <10 or tolerance test >0.1.

Bivariate analysis was done and all explanatory variables which have an association with the outcome variable at a p-value <0.25 was selected for multivariate analysis. Then multivariable analysis at a P-value <0.05 and AOR with 95% CI was used to measure the degree of association between independent variables and the outcome variable.

Result

The study was conducted from 136 facilities that incorporated all assigned health care workers in EPI service, gaining a 91% response rate.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The dominant age interval of EPI focal person across 136 health facilities of Wolaita zone is 26 to 35 years and the mean age of respondents were 28.2 years with a standard deviation of 5. More than half (84; 61.8%) of respondents were female. The majority (56; (41.2%) of the respondents were health extension workers (HEWs), while 38 (27.9%) were nurses. The educational background of the respondents indicated that 50 (36.8%) were HEW level-4 and 42 (30.9%) of them were degree level and above. The socio-demographic characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of EPI Focal Persons in Public Health Facilities and District Health Offices of Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia 2021 |

From a total of 136 health care workers included in this study, 53 (39%) of them had work experience of less than 2 years. Fifty-three (39%) of EPI focal persons interviewed took EPI related in-service training and, of 136 respondents, 90 (66.2%) did not use vaccine cold chain management guidelines during cold chain management.

Eighty-six (63.2%) health facilities who provided EPI services had taken EPI specific supportive supervision from their respective woreda or zonal health department. Regarding the type of fridge, the majority (91.9%) of health facilities had top opening vaccine refrigerators for vaccine cold chain management.

Infrastructure in Public Health Facilities

Greater than half of the public health facilities (91; 66.9%) use electricity as the main power source for the vaccine refrigerator, whereas the rest use solar options as the main power source for the vaccine refrigerator. Among the 91 (66.9%) health facilities that used electricity as the main power source for vaccine refrigerators, 25 (27.5%) used an automatic voltage stabilizer for vaccine refrigerators, 32 (31.2%) had a functional backup generator in the facility to use at a time of electric power break, and 132 (97.1%) health facilities had a separate room for the vaccine refrigerator.

Availability of Cold Chain Equipment

The results of this study indicated that 133 (97.8%) health facilities had functional vaccine refrigerators in the facilities, 108 (79.4%) had a cold box, 107 (78.7%) had ice packs, and 133 (97.8%) of them had vaccine carriers. Fifty-nine (43.4%) of the health facilities use a fridge tag for temperature monitoring in the facility, whereas 77 (56.6%) use a thermometer for temperature monitoring.

Knowledge of Health Care Workers on Cold Chain Management

The individual response was counted and calculated to classify respondents as having good knowledge and poor knowledge. Based on the knowledge score respondents were asked six questions and those who scored greater than or equal to 4 (75%) were considered as “good knowledge” and those who scored less than 4 considered as having “poor knowledge”. Accordingly, 107 (78.7%) respondents had good knowledge, while others had poor knowledge. Knowledge of health care workers towards cold chain management is shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Knowledge Towards Cold Chain Management Among Health Care Workers in Public Health Facilities and District Health Offices of Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia 2021 |

Attitude Towards Cold Chain Management Among Health Care Workers in Public Health Facilities and District Health Office

The result of the attitude assessment among the respondents in public health facilities of Wolaita zone indicate that the majority (89; 65.4%) of the respondents had a positive attitude towards vaccine cold chain management practices.

Cold Chain Management Among Health Care Workers in Public Health Facilities and District Health Offices

Eighty-three (61%) of the public health facilities had good cold chain management practice at a 95% CI (52.2–68.4), whereas 53 (39%) of public health facilities had poor cold chain management.

Associated Factors of Cold Chain Management

Bivariate Analysis

Results of bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that experience, sex, type of profession, EPI training, presence of cold chain guideline, supportive supervision, presence of cold box, presence of fridge tag and thermometer, presence of separate room, attitude and knowledge of respondents were candidate variables for a multivariable logistic regression model at a p-value <0.25.

Multivariable Analysis

The model was checked for fitness using the Hosmer and Lemeshow tests before running the multivariable analysis, which indicated that the model was fit. Thus, in the adjusted multivariable analysis at a p-value of less than or equal to 0.05 work experience of health professionals, presence of supportive supervision, EPI related training, and knowledge of health professionals were statistically significant.

Facilities whose cold chain is managed by health workers with two or more years of work experience had 2.8-times higher odds of good cold chain management than facilities whose cold chain is managed by health workers with less than two years of work experience: AOR (95% CI)=2.8 (1.13–6.74).

Health care workers who had a good cold chain management knowledge were 3.02-times more likely to practice cold chain management compared to health care workers with poor knowledge: AOR (95% CI)=3.02 (1.2–7.4). Health care workers who had taken in-service training on cold chain management were 1.86-times more likely to practice cold chain management than those who had not received in-service training: AOR (95% CI)=1.86 (1.36–9.84). Health care facilities with supportive supervision in their facilities were 2.71-times more likely to have good cold chain management compared to those health care facilities without supportive supervision: AOR (95% CI)=2.71 (1.1–7.14). Multivariable analysis for associated factors is shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Multivariable Analysis of Associated Factors for Cold Chain Management, Wolaita Zone, 2021 |

Discussion

Vaccine cold chain management is one of the most important challenges in public health facilities. This study assessed vaccine cold chain management and associated factors in public health facilities and revealed that 61% of public health facilities had a good cold chain management practice. This finding was consistent with studies conducted in South India (61.8%)16 and Oromia special zone Amhara region of Ethiopia (63%).17 On the other hand, this finding was lower than the findings in Benin City, Edo State Southern Nigeria (73.9%),18 and Bahir Dar city Ethiopia (71.4%).19 This study finding was higher than reports from the Northwest region of Cameroon (24%) and the three Indian states (7%) at Gujarat health facilities.20 The higher or lower differences could be due to the time of study period, socio-demographic characteristics, economic and cultural factors of the current study area and study settings and type of healthcare facilities. In addition, inadequacy and unavailability of the equipment and infrastructure used for cold chain management practice could be another possible reason for variation between the studies.

In this study having work experience greater than two years had a positive association with good cold chain management practice. This finding was similar to the study conducted in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia.19 This might be related with higher/longer work experience making them more familiar to cold chain management which helps them to acquire better essential information on cold chain management practice.

The current study revealed good knowledge of cold chain management had a positive association with cold chain management practice. This finding was similar with a study conducted in Bahir Dar city and East Gojjam Ethiopia.11,19 This could be associated with having in-service training regarding cold chain management which upgrades the knowledge and skill of health workers and benefits them to get updated information and then easily understand basic principles, standards of practice, and implement consistently on cold chain management.

In our study the presence of supportive supervision in the facility had a positive association with good cold chain management practice. This study was similar to the study conducted in Southern Nigeria.12 The possible explanation for this finding could be associated with the benefits that health workers gain updated information and support from their supervisors to fill their gaps regarding cold chain management and practice.

Some of the health facilities reported that there was high staff turnover, especially in those taking EPI training, which could be seen as a limitation of the study.

Conclusion

The result of the study indicated 61% of public health facilities had a good cold chain management practice in the study area. Greater than 2 years work experience, presence of supportive supervision, good knowledge on cold chain management, and training on cold chain management were predictors of good cold chain management practices.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Wolaita zone health department and all health facilities that provide us with necessary materials to conduct this research. We would also like to acknowledge the local health administration in the study area for their cooperation by providing all necessary information when needed.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Lin Q, Zhao Q, Lev B. Cold chain transportation decision in the vaccine supply chain. Eur J Oper Res. 2020;283(1):182–195. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2019.11.005

2. Lutukai M, Bunde EA, Hatch B, et al. Using data to keep vaccines cold in Kenya: remote temperature monitoring with data review teams for vaccine management. Global Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(4):585–597. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00157

3. Belete H, Kidane T, Bisrat F, Molla M, Mounier-Jack S, Kitaw Y. Routine immunization in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2015;29:1.

4. World Health Organization. Mid-Level Management Course for EPI Managers: Block III: Logistics: Module 9: Immunization Safety. World Health Organization; 2017.

5. Storage V, Toolkit H. CDC; 2019.

6. Peters T, Sayin L. Sustainable Cold Chain Development, in Cold Chain Management for the Fresh Produce Industry in the Developing World. CRC Press; 2021:55–68.

7. Dairo DM, Osizimete OE. Factors affecting vaccine handling and storage practices among immunization service providers in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(2):576–583. doi:10.4314/ahs.v16i2.27

8. Gebretnsae H, Hadgu T, Ayele B, et al. Knowledge of vaccine handlers and status of cold chain and vaccine management in primary health care facilities of Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia: institutional based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0269183. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269183

9. Amare G, Seyoum T, Zayede T, et al. Vaccine safety practices and its implementation barriers in Northwest Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2021;35(3):1.

10. Feyisa D, Ejeta F, Aferu T, Kebede O. Adherence to WHO vaccine storage codes and vaccine cold chain management practices at primary healthcare facilities in Dalocha District of Silt’e Zone, Ethiopia. Tropical Diseases. Travel Med Vaccines. 2022;8(1):1–13.

11. Bogale HA, Amhare AF, Bogale AA. Assessment of factors affecting vaccine cold chain management practice in public health institutions in east Gojam zone of Amhara region. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–6. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7786-x

12. Mohammed SA, Workneh BD, Kahissay MH, Gurgel RQ. Knowledge, attitude and practice of vaccinators and vaccine handlers on vaccine cold chain management in public health facilities, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247459. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247459

13. Pambudi NA, Sarifudin A, Gandidi IM, et al. Vaccine cold chain management and cold storage technology to address the challenges of vaccination programs. Energy Rep. 2022;8:955–972. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.12.039

14. Wolaita. Zonal Health Department Annual Report. Sodo: WZHD; 2021:8–10.

15. Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121–126. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.116232

16. Rao S, Naftar S, Unnikrishnana B. Evaluation, awareness, practice and management of cold chain at the primary health care centers in Coastal South India. J Nepal Paediatr Soc. 2012;32(1):19–22. doi:10.3126/jnps.v32i1.5946

17. Mohammed SA, Workneh BD. Vaccine Cold chain management in public health facilities of Oromia special zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: mixed Study. J Drug Alcohol Res. 2021;10(8):1–9.

18. Ogboghodo EO, Omuemu V, Odijie O, et al. Cold chain management: an assessment of knowledge and attitude of health workers in primary health-care facilities in Edo State Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2018;21(2):75. doi:10.4103/smj.smj_45_17

19. Mulatu S, Tesfa G, Dinku H. Assessment of factors affecting vaccine cold chain management practice in Bahir Dar City Health institutions, 2019. Am J Life Sci. 2020;8(5):107–113. doi:10.11648/j.ajls.20200805.14

20. Yakum MN, Ateudjieu J, Pélagie FR, et al. Factors associated with the exposure of vaccines to adverse temperature conditions: the case of North West region, Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1257-y

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.