Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 5

Using professional interpreters in undergraduate medical consultation skills teaching

Authors Bansal A, Swann J, Smithson W

Received 18 July 2014

Accepted for publication 17 August 2014

Published 21 November 2014 Volume 2014:5 Pages 439—450

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S71332

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Video abstract presented by Aarti Bansal.

Views: 624

Aarti Bansal,1 Jennifer Swann,1 William Henry Smithson2

1Academic Unit of Primary Medical Care, University of Sheffield, UK; 2Department of General Practice, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Abstract: The ability to work with interpreters is a core skill for UK medical graduates. At the University of Sheffield Medical School, this teaching was identified as a gap in the curriculum. Teaching was developed to use professional interpreters in role-play, based on evidence that professional interpreters improve health outcomes for patients with limited English proficiency. Other principles guiding the development of the teaching were an experiential learning format, integration to the core consultation skills curriculum, and sustainable delivery. The session was aligned with existing consultation skills teaching to retain the small-group experiential format and general practitioner (GP) tutor. Core curricular time was found through conversion of an existing consultation skills session. Language pairs of professional interpreters worked with each small group, with one playing patient and the other playing interpreter. These professional interpreters attended training in the scenarios so that they could learn to act as patient and family interpreter. GP tutors attended training sessions to help them facilitate the session. This enhanced the sustainability of the session by providing a cohort of tutors able to pass on their expertise to new staff through the existing shadowing process. Tutors felt that the involvement of professional interpreters improved student engagement. Student evaluation of the teaching suggests that the learning objectives were achieved. Faculty evaluation by GP tutors suggests that they perceived the teaching to be worthwhile and that the training they received had helped improve their own clinical practice in consulting through interpreters. We offer the following recommendations to others who may be interested in developing teaching on interpreted consultations within their core curriculum: 1) consider recruiting professional interpreters as a teaching resource; 2) align the teaching to existing consultation skills sessions to aid integration; and 3) invest in faculty development for successful and sustainable delivery.

Keywords: interpreter, communication skills, curriculum

Background

In this paper, we report on our experience of developing and introducing an interpreted consultation skills session using professional interpreters in the core undergraduate medical curriculum.

In the UK, The General Medical Council (GMC) states in its document “Tomorrow’s Doctors”, that medical students must “Communicate clearly, sensitively and effectively with individuals and groups regardless of their age, social, cultural or ethnic backgrounds or their disabilities, including when English is not the patient’s first language”.1 Students at the University of Sheffield Medical School have a 3-hour diversity seminar in their fourth year. This provides an essential foundation as to the importance of cultural influences on the consultation necessary for conducting interpreted consultations.2 However, specific teaching on skills required for interpreted consultations was identified as a gap in the curriculum.

The 2011 UK Census showed that there are 0.9 million people living in England and Wales who are “not proficient in English” and that only 65% of the “not-proficient in English” group described themselves as being in “good health” compared to 88% of those who are “proficient in English”.3 Studies have shown that patients with limited English proficiency (LEPs) often have poorer uptake of preventative care, decreased comprehension of their diagnoses, reduced adherence to treatment, lower satisfaction with care, and increased adverse events.4–8

Interpreters appear to be underused by health professionals.9 This is sometimes related to a lack of availability of professional interpreting services but is also due to a culture of “getting by” without adequate interpretation.10 There is also overreliance on untrained, ad hoc bilingual staff and family members.11 Use of untrained interpreters may result in major errors in interpreting.12 Family members may sometimes be the patient’s preferred interpreters, but may also present issues of confidentiality and control.13 A systematic review in 2007 showed that the use of professional interpreters improved the quality of clinical care to approach or equal that for patients without language barriers.14 Comprehension, utilization of care, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care were improved, and in all these areas, professional interpreters were superior to untrained ad hoc and family interpreters.

A systematic review of cultural competence interventions showed that those targeting language barriers helped improve the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals.15 Given the evidence that professional interpreters significantly improve health outcomes for LEPs, one of the most important findings of training health professionals on consulting through interpreters is that they are more likely to use a professional interpreter.16

When developing interpreted consultation teaching for final year medical students, we considered it important to recruit professional interpreters to play the role of the interpreter in order to demonstrate best practice. The literature provides little guidance on recruiting professional interpreters to this role.

Institutional context

During their final primary care attachment, small groups of six to eight students are given the chance to role-play the doctor in three afternoon consultation skills workshops using actors as patients and general practitioner (GP) tutors as facilitators. Observing students give peer feedback based on the Calgary–Cambridge observation guides.17 These small groups have the same GP tutor for all three sessions.

Finding core curricular time is often a constraint to innovation in medical curricula. We overcame this through conversion of the third existing consultation skills teaching session into an interpreted consultation skills session.

Design of teaching

The aim of the teaching session was to improve medical students’ ability to provide care for patients with LEP. The learning objectives were:

- To improve student confidence in consulting through interpreters.

- To recognize the strengths of using a professional interpreter in patients with LEP.

- To understand and experience the various techniques that help optimize the use of an interpreter in a triadic consultation.

There were four main principles guiding our design of the interpreted consultation skills workshop.

Using professional interpreters in role-play

In order for students to recognize the strengths of using professional interpreters, it was considered important to recruit professional interpreters to role-play as interpreters. Using professional interpreters overcame the problem of how to train lay bilingual people in the skills of professional interpreters. Further, this would be an opportunity for students to learn from professional interpreters about their perspectives on what is helpful in real-life consultations.

Professional interpreters recruited by the Sheffield Community Access and Interpreting Service (SCAIS), undergo a thorough language assessment of all the languages they speak as well as training on codes of practice, including the importance of full and accurate translation, confidentiality, and impartiality. Initial training lasts a minimum of 2 days and many go on to complete the Diploma in Public Service Interpreting from the Chartered Institute of Linguists.

Experiential learning techniques

There is a consensus in the literature that the most effective teaching methods for consultation skills teaching are experiential and that instructional methods are not effective.18 The essential characteristics of experiential learning about consultations skills include small-group/one-to-one learning, observation, detailed individualized feedback, and practice of skills.19 Published articles on teaching interpreted consultations that describe using role-play-based teaching report an improvement in student knowledge and skills.20–22 Some institutions have attempted to use web-based modules; however, evaluation of these courses has shown an improvement in knowledge of how to conduct interpreted consultations but no improvement in skills.23,24

Integration to core curriculum

Integrating this teaching with existing core consultation skills teaching would make sure that all students received teaching on this core skill as per the GMC. Additionally, it would help make the point that interpreted consultation skills are an extension of the standard consultation skills, with many skills being transferable to same-language consultations (Table 1).

| Table 1 Skills for consulting through interpreters |

Building in sustainability

GP tutors learn consultation skills during postgraduate specialist training and therefore have the foundations to facilitate such teaching. However, they are unlikely to have been taught how to consult though interpreters and, depending on where they were working, would have variable experience of interpreted consultations. Staff development of the small-group GP tutors was considered important to build sustainability into the session through developing skills, sharing a common vision, and creating a pool of expertise for future training needs.

Development of teaching

Format of session

We decided to use the existing resource of GP tutors who facilitate consultations skill sessions for two reasons: firstly, as they were experienced at experiential small-group teaching, and, secondly, as this would capitalize on the secure, small-group dynamic that they would have built up in the previous weeks.

Alongside the Calgary–Cambridge observation guides, additional feedback guidance was developed for students to use in giving peer feedback (Table 2). This was adapted from an interpreter scale that was developed for formative assessment of standardized patient interpreted consultations and validated against the Interpreter Impact Rating Scale (IIRS) and the Faculty Observer Rating Scale (FORS).25

| Table 2 Feedback sheet guide for observing students in interpreted consultations |

In our standard consultation skills sessions, each small group has the same actor for each session. This allows the GP tutor facilitating the session more agency in how long to spend on each scenario. For interpreted consultation skills teaching we required two people speaking the same language (language pairing) to play patient and interpreter for each scenario. We considered the model of training each language pairing in one scenario each and rotating them between small groups.21 However, we decided to maintain tutor flexibility of facilitation by allocating a language pairing to each small group for the whole session. Language pairings working with a student group for a whole session would need to learn more scenarios than having them rotate through groups; however, this had the advantage of minimizing the change to process for both students and tutors and reducing the risk of stereotyping through the inadvertent linkage of some scenarios with certain communities. The additional cost of having two people working with a small group instead of one was small and easily accommodated by the medical school.

Development of scenarios

In line with existing consultation skills sessions, scenarios were written to require the student to employ a patient-centered approach to explore the patient’s ideas, concerns, and expectations. The cultural aspects of these ideas, concerns, and expectations were written so that they could be true for patients from any community. Scenarios were developed from the real-life interpreted consultations experienced by GPs working in the department as well as through consultation with academics at the University of Leeds.21 Although the use of family interpreters can have disadvantages, this form of interpretation is common and it was considered important that students learn strategies to manage potential challenges such as the family member partially blocking access to the patient by speaking for them, not fully translating or having their own agenda. Similarly, telephone interpretation, which may be the only option or preferred option in some situations, has additional challenges to do with the lack of nonverbal communication. Four scenarios were written for use in the session: two for face-to-face professional interpreters, one for a family interpreter, and one for professional telephone interpretation. The topics for the scenarios were of a patient with a headache who has an underlying grief, a patient attending for blood results that show a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, a patient with viral diarrhea attending with a family interpreter whose agenda is to have the patient continue to work in the family food business, and a patient with indigestion (telephone interpreter).

GP tutor training

All existing GP tutors were trained in how to facilitate the session in 3-hour training sessions which contained the same elements of learning as the proposed student session. The training included looking at the evidence basis for this teaching in order to highlight the importance of this teaching in terms of patient health outcomes. Then a brainstorming exercise was carried out about GP tutors’ experience of what makes such consultations effective, as well as exercises illuminating the unconscious use of language full of idioms and medical jargon. Instead of role-play, we examined videotaped interpreted consultations from the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) resource “Valuing Diversity”.26

A handbook was developed as a resource for the GP tutors to help them deliver the sessions and covered all the material in the training sessions including the scenarios, student feedback guide, and how to draw out learning points. The handbook also lent sustainability to faculty training, as all new GP tutors shadow an existing GP tutor for a module (8 weeks) before they start teaching and so would have seen the teaching in action. The handbook would then act as additional guide to these GP tutors and substitute the need for further and on-going faculty training workshops.

Recruitment and training of interpreters

For recruitment of language pairings, we tried at first to find bilingual actors to play the role of patients who could work with professional interpreters. However, these were difficult to find and therefore it was decided to recruit language pairings of interpreters and train them to act in the role of the patient as well as family interpreter. This work was advertised through the local interpreting service, and interested language pairings were invited to training workshops. The workshops had similar elements to the GP tutor workshops although with a greater emphasis on practicing the role of the patient and family interpreter in the scenarios. Volunteer medical students were recruited to play the role of the doctor in these workshops so that we could refine the level of challenge in the scenarios as well as make sure we had given enough information on the scenario for the students to read prior to participating in the role-play. A number of interpreters struggled to act as patients or as a family interpreter, as this did not involve working from a script but understanding the role and being able to act flexibly in response to the student playing the doctor. It was therefore possible to recruit only six language pairings, who were then employed by the university on an ad hoc basis. The languages recruited were Cantonese, Mandarin, Arabic, Spanish, Punjabi, and Polish.

In the first year of delivery (2011), some of the interpreters canceled at short notice, resulting in the breaking of their language pairs. This was overcome in several ways such as asking a bilingual student of the right language from the small group to fill in as “patient”, drafting in a contact of the interpreter present, or asking an interpreter pairing to do two groups back to back. By employing these strategies, no sessions had to be canceled.

It was not possible to fully investigate the reasons for these late cancelations, although in some instances, it was a case of unforeseeable family issues taking priority. It was noted that the interpreters were being paid the same as other actors, and that this was less than for normal National Health Service (NHS) work, which may have taken priority. Also it was hypothesized that the infrequent commitment required from interpreters of only two sessions every 3–4 months was not enough to command loyalty to the program.

After running the session for a year (2011), recruitment of the interpreters was changed. From 2012, interpreters have been recruited directly from the local interpreting service instead of by the university on an ad hoc basis. This has had three advantages. Firstly, it puts the interpreter pay for the teaching session at par with their clinical work, eliminating the problem of NHS work being given priority. Secondly, interpreters deal with the same employer for all their work, easing processes. Thirdly, the interpreting service has access to other interpreters of the required language at the last minute if this is required.

Following the change in process to recruiting professional interpreters directly from the interpreting service, there have been no further issues with interpreter attendance in 2012. Since the session was first introduced, a cohort of professional interpreters has been developed who have worked with our medical school for a period of time. Annual training for our professional interpreters maintains quality of teaching and reinforces commitment to the session. This training is delivered by a GP tutor and a language pairing of interpreters who have been involved in the teaching session from the start and who are committed to its continuation. In terms of GP tutor training, on-going sustainability was demonstrated by two new GP tutors who joined in 2012. These tutors were able to deliver the sessions independently after shadowing an existing tutor for a single session and then using the handbook.

Evaluation of teaching

Methods

Evaluation of the session was sought in two ways: firstly through a student questionnaire, and secondly, through GP tutor feedback. Ethics approval for these two forms of evaluation was granted by the University of Sheffield Medical School’s Ethics Committee.

Student questionnaire

A student questionnaire was developed containing quantitative and qualitative components to evaluate the learning objectives of the session (Supplementary material). It was presented to students at the end of the teaching session in order to maximize recruitment.

A confidence rating ranking scale using a Likert scale with five categories was used to determine whether the students felt that the teaching had resulted in a change in their self-rated ability. Students were asked to rate their confidence in consulting through interpreters “before the session” and “after the session” on the same questionnaire. As they were recording their “confidence before the session” retrospectively, this had the potential to exaggerate their response. We tried to mitigate this effect by placing the questions on separate pages.

A nonparametric statistical hypothesis test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, was used to compare the two measurements (before and after) on the single (student) sample to assess whether the population mean ranks differed. P-values <0.05 were regarded as significant.

Qualitative free-text data was obtained through an open-ended question on what they felt had informed any change in confidence.

Students were asked to tick which characteristics of interpretation they thought were useful so that these could be matched against the strengths of a professional interpreter.26 An options list of possible characteristics was offered and included those associated with professional training (accuracy, neutrality, confidentiality, and professional training) and those that are not (known to the patient). This was done to provide an internal check for reliability.

Knowledge and understanding of the various techniques that are helpful in interpreted consultations were assessed by asking students to mark techniques against a scale of usefulness. Again, statements on desirable techniques were interspersed with undesirable techniques to check whether the statements were read and answered consciously.

Students were also asked whether they would recommend the session to their peers. An open-ended question for further comments or suggestions was included to allow students to expand on their feedback.

In terms of Kirkpatrick’s four-level model of evaluation, the questionnaire looked at two levels of evaluation outcomes: Level 1 (reaction) and Level 2 (learning). However, it was unable to look at Level 3 (behavior), which would need longitudinal follow-up to see whether the skills learned in training were being employed by doctors in their clinical practice, or Level 4 (results) to ascertain whether patient outcomes had actually been improved as a result of this training.

Over 2 years, 274 students were asked to fill in the questionnaire. The questionnaires were numbered, and responses were coded and entered into an SPSS database for analysis. Thematic analysis of the student comments from the open-ended questions was conducted separately by the lead author and a colleague familiar with the session.

GP tutor feedback

GP tutor feedback was sought at the end of the first year of implementation through group discussion. The group discussion format was used to allow GP tutors the opportunity to identify and discuss the potential strengths and weaknesses of the session and for the possibility of group consensus on any view about future developments. We used a convenience sample of the eight GP tutors due to teach the first module of 2012. These tutors had all taught at least two modules in the first year of implementation. At the time we had a total of 13 small-group GP tutors of whom eight work in any given module, and there are four modules in a year. As the allocation of teaching modules is a random process with eight tutors constituting over 60% of all tutors, the group was considered a representative sample of GP tutors.

Participant information sheets and consent forms were included in the University Ethics Approval to conduct the feedback groups. GP tutors were emailed invitations to participate, with an attached information sheet. This detailed the purpose of the feedback group, its voluntary nature, that they were free to withdraw at any time, why they had been chosen, and how the data would be recorded, kept secure, and anonymized.

The lead author facilitated the group discussion, with another researcher taking field notes to aid transcription. The group discussion lasted approximately 1 hour and was audiotaped and later transcribed using a transcription service. Thematic analysis was conducted independently by both researchers, who then met to agree on key themes.

Results

Student questionnaire

The response rate was 89% (243/274) over the 2 years. Ninety-four percent (228/243) of students marked that they would recommend the session to their peers.

Twenty-four percent (58/243) of students provided additional free-text comments in the “any other comments/suggestions” area. The comments concentrated on the usefulness of the teaching to future clinical practice and requests for more teaching in this. Requests for more teaching were further detailed with suggestions on how this may be achieved, such as additional sessions or smaller groups.

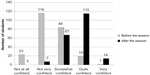

Figure 1 illustrates a clear positive shift in confidence with most students going up one or two points on the Likert scale. This shift was statistically significant (using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test) with a P-value of <0.001. There was one student whose confidence decreased from “very confident” to “quite confident”. Twelve (5%) students did not change in confidence.

| Figure 1 Student self-rated change in confidence in consulting through interpreters before and after the teaching session. |

Table 3 summarizes the themes that emerged from the factors students thought had influenced their change in confidence.

| Table 3 Student free-text themes on factors influencing change in confidence |

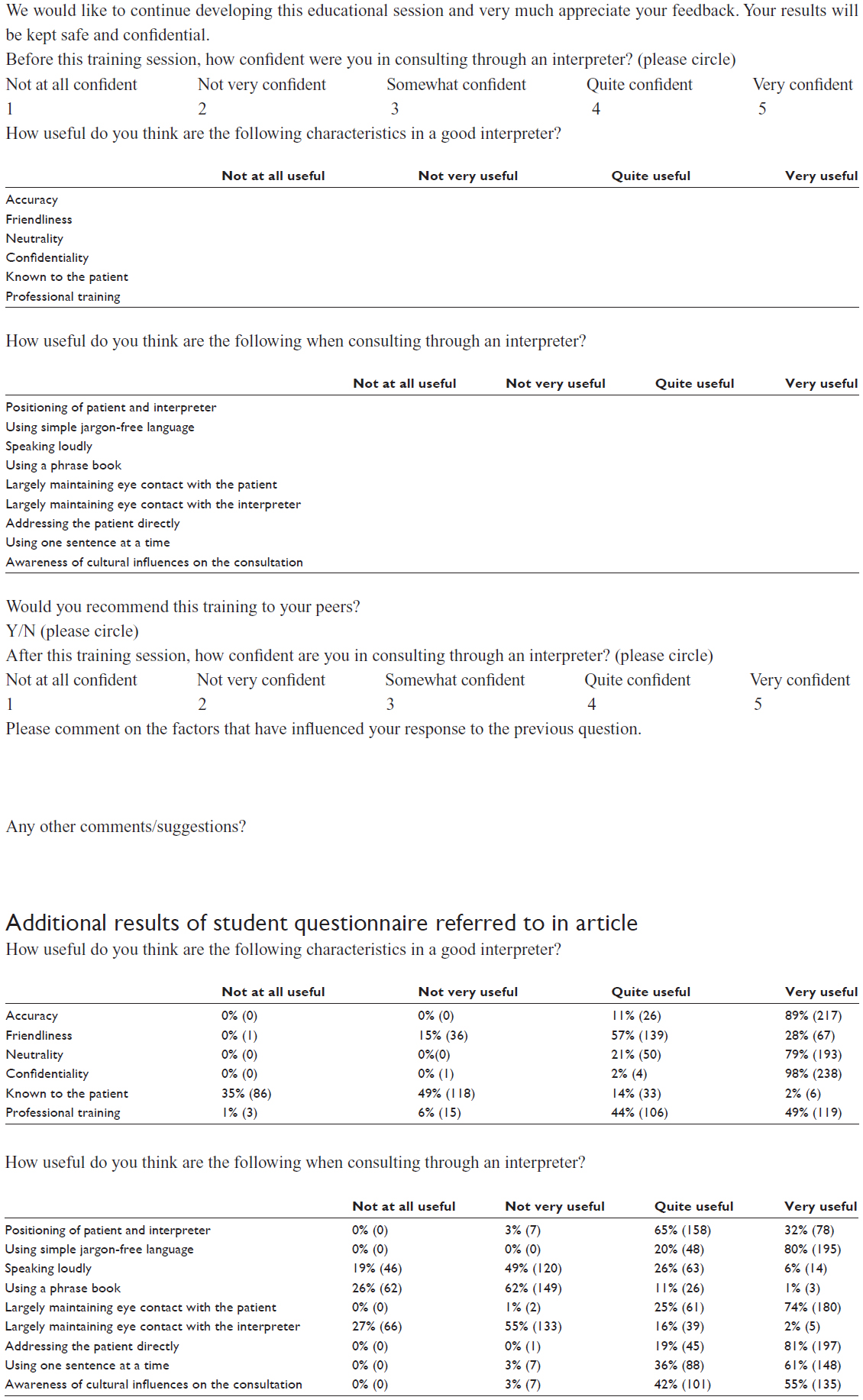

Students consistently ticked as “useful” the attributes associated with professional interpreters such as accuracy (100%), neutrality (100%), confidentiality (100%), and professional training (97%), as opposed to those that are not, such as “known to the patient” (16%) (Supplementary material).

Students marked as “useful” those skills and techniques that are associated with effective interpreted consultations such as positioning of patient and interpreter (97%) maintaining eye contact with patient (99%), addressing patient directly (99%), and using simple jargon-free language (100%), and marked those that are not associated with effective consultations as “not useful” such as largely maintaining eye contact with interpreter (84%) and speaking loudly (68%) (Supplementary material).

Feedback from GP tutors

The GP tutors all expressed support and commitment to the teaching on the basis of its value to medical students’ future clinical practice. Additionally, some tutors mentioned that the students were well aware of the importance of this session. The following quotes illustrate these sentiments.

I think it’s extremely effective. There are very few things where one session makes a significant impact on your career and this is one of them. [GP 8]

And I think they are really up for it. They are aware of the fact that they are going to come across it or they’ve already come across it. [GP 6]

The majority of GP tutors felt that the session integrated well into the core consultation skills teaching in terms of process as well as learning. This is illustrated by the following quote:

It’s the same skills as the Cambridge–Calgary framework but just emphasized. [GP 1]

Only one tutor partly dissented from this view, being concerned that conversion of an existing session may have had a negative effect on acquisition of other consultation skills.

It would have been better to have this session as an extra session so that students could all still have three attempts at normal consultation skills. [GP 3]

All tutors found that professional interpreters facilitated teaching as they engaged the students in an authentic experience as well as giving them practical tips from real clinical practice. This is illustrated by the following quotes:

I think the students actually listen to what the interpreters say because this is real and I found that quite valuable that they’re getting it direct from somebody not me telling them this is what I found. [GP 2]

The interpreter I had for my session was excellent and gave them lots of actual practical tips and kind of said this is what makes my job harder or easier. [GP 4]

One tutor also pointed out that, in order for the teaching resources to be effective, professional interpreters need to be engaged with the teaching and we should bear this in mind during recruitment.

Source some of the good ones from the ones that were really keen on the role. You are using them much more as a teaching resource then. [GP 6]

All tutors commented that they felt the training had been important to help them deliver the session. They felt that additional training sessions for new tutors were not required given that the existing training process involved shadowing an existing tutor for a module and they would have the benefit of the handbook guide. There were no dissenting voices.

The training day was very good and I think you have to think about people who are coming in the future so I think the handbook does cover kind of what we were discussing at the training. [GP 2]

A strong theme that emerged in the GP tutor feedback was the usefulness and relevance of the training they had received to their clinical practice and how this training had filled a gap in their own skills. The following quotes are illustrative:

It’s revolutionized how I do my own practice with interpreting patients. [GP 2]

It makes you feel some of our colleagues should go through the same training. [GP 5]

In terms of improvements in the content of the session, one GP mentioned that her students had felt they would have all liked to have had an opportunity to play doctor in this teaching session.

One of the main things that my students have said is that they would all like to practice with the interpreters. It is like oh I wanted to do it with them and I wouldn’t have volunteered last week if I’d have known I could have done it with them this week. [GP 7]

As this mirrored the student feedback, the GP tutors were asked about potentially “hot-seating” to give the students all an opportunity for active participation. This involved the scenario being interrupted halfway and another student coming in to complete the consultation. This was debated but rejected, as the general consensus was that observing students are still very much active in learning and should get as much out of the experience. This was consistent with the principle guiding the other consultation skills sessions.

Discussion

The purpose of developing this session on interpreted consultations was to improve students’ ability to care for patients with limited English proficiency. The analysis of the evaluation provides many reasons for optimism that the delivered teaching session did indeed move toward this aim.

Students’ self-reported confidence moved definitively (Figure 1). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated a highly significant shift, showing this increase in confidence to be a true result. The large proportion of students who gained confidence in the session, and their comments on the reasons behind this, reinforce the need for this teaching session. Although measuring student self-rated confidence is evaluation at Level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s model (reaction), the GP tutors’ comments about the applicability of the training to their own clinical practice could be argued to equate to Level 3 on the Kirkpatrick model, indicating transfer of learning and change of behavior.27 The tutor comments add face validity to the applicability of this training for future clinical practice and are a useful surrogate for longitudinal studies.

The qualitative feedback in the student free-text comments (Table 3) helps to both understand and validate the quantitative shift in student confidence and represents a form of methodological triangulation. Many students commented on how they had not previously participated in interpreted consultations and this was not covered elsewhere in the curriculum, which would explain the general low level of confidence prior to the session. The magnitude of the shift (in most cases being one or two points up the Likert scale) is what would be expected from a single teaching session. Students recognized that confidence would come with iteration of the experience and reflection on the experience. Indeed, the small-group experiential nature of the learning was mentioned by many students as important in helping to improve their confidence. This is consistent with evidence on the best methods for learning consultation skills.18 In detailing their increased ability to conduct interpreted consultations, students often commented on specific skills that constituted new knowledge for them (positioning, use of first person, eye contact, effect of jargons, etc.). This qualitative data tallies with the tick-box questions (Supplementary material) where students have only marked as “useful” those skills that are known to be important to effective interpreted consultations.28

Learning on cultural aspects of interpreted consultations was embedded in the scenarios, and these were commented on as being realistic, diverse, and challenging.

In terms of recognizing the importance of using a professional interpreter, students marked as “useful” attributes associated with professional interpreters such as accuracy, confidentiality, professional training, and neutrality (Supplementary material). Student free-text comments highlight that feedback from the professional interpreters and their insights into real-life practice are important to their learning, and this is supported by GP tutor comments on high student engagement with professional interpreters.

General comments on “more sessions” and “really useful” suggest students felt that this teaching was filling a real educational void important to future clinical practice. Further support for the effectiveness of teaching session is shown by the fact that 94% of students would recommend it to their peers.

Limitations of the evaluation

There are certain limitations to the evaluation. The student evaluation is self-reporting and, as this teaching session was addressing a gap in learning, any teaching (regardless of length, design, and quality) may have been highly evaluated. In other studies, web-based teaching on consulting through interpreters was highly regarded by students despite the fact that, compared to role-play-based methods, it did not actually improve their skills.23 Also we recognize that students were not able to make an assessment of whether there had been a loss of learning from the conversion of an existing session. Having said this, it is interesting that none of the students commented on a loss of a “usual” consultation skills session which may have been, as they have had other opportunities for consultation skills training in previous years. Also, most of the tutors saw the session as teaching skills required for both “usual” and interpreted consultation skills.

Despite these limitations, 2 years of consistency in student feedback and positive feedback from GP tutors, gives credence to the conclusion that the session effectively delivered on teaching aims and that these aims were highly valued by students and tutors alike.

Recommendations

Consider recruiting professional interpreters as a teaching resource

The involvement of professional interpreters in this teaching was highly valued by tutors who felt that it improved student engagement with the session. However, we found that, although professional interpreters did not need any guidance to work in the role of a professional interpreter, many professional interpreters found it hard to act as patients or indeed to act in the family interpreter role for one of the scenarios. Some institutions may find that they have access to bilingual actors who can pair up with professional interpreters and act as patients. In this case, professional interpreters would only need to learn to act the role of a family interpreter if a family interpreter scenario is included in the teaching. However, training for interpreters also included the nature and purpose of the session and how to give students effective feedback, and we would therefore recommend this. We have instituted annual training for our professional interpreter pairings, which allows us to maintain quality as well as increase recruitment as required. Recruitment of professional interpreters directly from the interpreting service proved a reliable and sustainable way of providing role-play resources and we recommend this as an option to others wishing to develop interpreted consultation teaching.

Align the teaching to existing consultation skills sessions to aid integration

By integrating well in terms of process (small-group experiential learning), resources (GP tutors), and teaching content (Calgary–Cambridge consultation model), the complexity of the change was minimized, one of the key factors in terms of success in educational change.29 As this session works as an extension of usual consultation skills teaching, even where there are resource constraints in terms of core curricular time and funding, it can be integrated into core teaching through conversion of an existing consultation skills session.

This approach likely to be generalizable to other institutions interested in developing such teaching as they can align the teaching on the basis of their own standard consultation skills teaching and resources.

Invest in faculty development for successful and sustainable delivery

Previous published work has described how faculty development can be a powerful instrument of curricular change by developing consensus on educational content and generating support and enthusiasm for implementation of the change.30 Implementation of change often relies on the degree of value congruence between the developers and implementers of change. Value congruence is described as the extent to which individual teacher’s codes of practice coincide with the training providers’ views of “good practice”.31 In order to generate enthusiasm and support for delivering interpreted consultations, the tutor training sessions started with an outline of the evidence for the importance of this teaching. This value congruence was articulated by the GP tutors in feedback groups and can explain why, despite the problems with interpreter reliability in the first year, support from the GP tutors remained strong.

It has been noted that very few programs plan for the training of new members of staff who arrive after the program commences.29 Staff development through training all existing GP tutors significantly enhanced the sustainability of the session by providing a cohort of tutors skilled in facilitation and able to pass on their expertise to new staff through the existing shadowing process. This was backed up through written teaching resources in the form of a tutor handbook. Indeed, new tutors who joined us after the initial training was over did not require any training over and above existing shadowing processes. Staff development was therefore built in to the program without the need for on-going training programs. We recommend investing in staff development as the basis of successful and sustainable delivery.

Conclusion

Our experience is consistent with previously published work in terms of the confidence and skills students gain through participating in teaching on interpreted consultations. What this work adds is that this teaching can be integrated into the curriculum even where there are resource constraints through alignment with existing consultation skills sessions. Also, training GP tutors to facilitate this session had a positive impact on their own ability to consult through interpreters, lending face validity to this teaching as well as sustainability to the delivery of the session. Finally, our experience suggests that professional interpreters can be recruited and trained as teaching resources and their real-life clinical experience can engage students in the learning. In terms of improving health outcomes for patients with LEP, the use of professional interpreters demonstrates best practice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teaching team at the Academic Unit of Primary Medical Care, University of Sheffield, who supported this initiative, the GP tutors for their enthusiasm, and all the interpreters who took part in this teaching.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Outcomes and Standards for Undergraduate Medical Education. London: GMC; 2009. | |

Diamond LC, Jacobs EA. Let’s not contribute to disparities: the best methods for teaching clinicians how to overcome language barriers to health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:S189–S193. | |

Office for National Statistics. English Language Proficiency in England and Wales. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Language. Accessed July 16, 2014. | |

Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Katz SJ, Welch HG. Is language a barrier to the use of preventive services? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:472–477. | |

Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26:1119–1128. | |

Crane JA. Patient comprehension of doctor-patient communication on discharge from the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:1–7. | |

Gandhi TK, Burstin HR, Cook EF, et al. Drug complications in outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:149–154. | |

Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:60–67. | |

Lee KC, Winickoff JP, Kim MK, et al. Resident physicians’ use of professional and nonprofessional interpreters: a national survey. JAMA. 2006;296:1050–1053. | |

Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A. Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:256–262. | |

Bischoff A, Hudelson P. Communicating with foreign language-speaking patients: is access to professional interpreters enough? J Travel Med. 2010;17:15–20. | |

Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111:6–14. | |

Leanza Y, Boivin I, Rosenberg E. Interruptions and resistance: a comparison of medical consultations with family and trained interpreters. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1888–1895. | |

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727–754. | |

Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence – a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–373. | |

Bischoff A, Perneger TV, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Stalder H. Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:541–546. | |

Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary–Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ. 1996;30:83–89. | |

Aspegren K. BEME Guide No 2: teaching and learning communication skills in medicine – a review with quality grading of articles. Med Teach. 1999;21:563–570. | |

Howells RJ, Davies HA, Silverman JD. Teaching and learning consultation skills for paediatric practice. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:367–370. | |

Jacobs EA, Diamond LC, Stevak L. The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:149–153. | |

Escott S, Lucas B, Pearson D. Lost in translation: using bilingual simulated patients to improve consulting across language barriers. Educ Prim Care. 2009;20(2):93–98. | |

McEvoy M, Santos MT, Marzan M, Green EH, Milan FB. Teaching medical students how to use interpreters: a three year experience. Med Educ Online. 2009;14:12. | |

Lie D, Bereknyei S, Kalet A, Braddock C. Learning outcomes of a web module for teaching interpreter interaction skills to pre-clerkship students. Fam Med. 2009;41:234–235. | |

Ikram UZ, Essink-Bot M, Suurmond J. How we developed an effective e-learning module for medical students on using professional interpreters. Medical teacher. 2014;0:1–6. | |

Lie D, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH, Encinas J, Ahearn S, Boker JR. Assessing medical students’ skills in working with interpreters during patient encounters: a validation study of the Interpreter Scale. Acad Med. 2009;84:643–650. | |

Kai J. Valuing Diversity: A Resource for Health Professional Training to Respond to Cultural Diversity. 2nd ed. London: RCGP; 2006. | |

Praslova L. Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in Higher Education. Educ Asse Eval Acc. 2010;22:215–225. | |

Phelan M, Parkman S. How to do it – work with an interpreter. Br Med J. 1995;311:555–557. | |

Fullan M, Stiegelbauer S. The New Meaning of Educational Change. 2nd ed. London: Cassell Educational Ltd; 1991. | |

Steinert Y, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Fuks A. Faculty development as an instrument of change: a case study on teaching professionalism. Acad Med. 2007;82:1057–1064. | |

Harland J, Kinder K. Teachers’ continuing professional development: framing a model of outcomes. Br J In-Serv Educ. 1997;23:71–84. |

Supplementary material

Consulting through interpreters: student evaluation form

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.