Back to Journals » Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice » Volume 9

Unlicensed “Special” Medicines: Understanding the Community Pharmacist Perspective

Authors Wale A , Ireland M, Yemm R , Hiom S, Jones A, Spark JP, Francis M, May K, Allen L, Ridd S, Mantzourani E

Received 21 May 2020

Accepted for publication 16 July 2020

Published 13 August 2020 Volume 2020:9 Pages 93—104

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IPRP.S263970

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Jonathan Ling

Alesha Wale,1 Mark Ireland,2 Rowan Yemm,1 Sarah Hiom,3 Alison Jones,3 John Paul Spark,3 Mark Francis,4 Karen May,5 Louise Allen,5 Steve Ridd,6 Efi Mantzourani1,7

1School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, UK; 2Community Pharmacy Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK; 3St. Mary’s Pharmaceutical Unit, Cardiff, Wales, UK; 4Swansea Bay University Health Board, Swansea, Wales, UK; 5Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, Swansea, Wales, UK; 6Mayberry Pharmacy, Cardiff, Wales, UK; 7NHS Wales Informatics Service, Cardiff, Wales, UK

Correspondence: Efi Mantzourani Email [email protected]

Objective: Community pharmacy staff are responsible for obtaining and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines to patients in primary care. Less well-defined parameters for safe and effective use of unlicensed compared to licensed medicines, along with issues around maintaining consistency between care settings or among manufacturers, have been associated with increased risks. This study aimed to explore the views and experiences of community pharmacy staff on accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines to patients in Wales and the perceived impact of challenges faced on patient care.

Methods: A qualitative, phenomenological approach was employed, involving semi-structured interviews with pharmacists and pharmacy technicians working at one small chain of community pharmacies in Wales. The interview schedule focused on the personal experiences and perceptions of the participants on the processes involved in accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines from a community pharmacy. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Results: A total of six participants completed the interview. Three main themes were constructed from inductive thematic analysis of the transcribed interviews: requirement for additional patient responsibilities; influences on the confidence felt by pharmacy staff when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines; and continuity of supply.

Conclusion: This study gives a preliminary insight into the views and experiences of community pharmacy staff in Wales when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines. Further research is required to see if these views and experiences are representative of community pharmacy staff across the country.

Keywords: unlicensed medicines, “special” medicines, specials, community pharmacy, transfer of care, medicines supply, transmural care, off-label, compounding

Introduction

In the United Kingdom (UK), it is expected that medicines being sold and supplied to the public have undergone clinical trials and hold a license, or marketing authorisation1 granted by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). This license ensures a medicine has passed through clinical trials and has met the MHRA’s standards of safety and efficacy.2 However, sometimes there is no licensed product available to treat a patient’s specific clinical needs, for example, those in paediatric and elderly populations, as medicines are rarely tested and licensed for use within these age groups;3 those with rare diseases;4,5 those physically unable to take a licensed medicine, such as patients with dysphagia,6 or in times of drug shortages.7 When no suitable licensed product is available, unlicensed medicines, often known as ‘specials’ are supplied. Unlicensed “special” medicines do not hold a marketing authorisation and therefore have not been held to the same standards of safety and efficacy testing as licensed medicines.8 It has been suggested that the resulting less well-defined parameters for their safe and effective use, along with issues around maintaining consistency between care settings or among manufacturers,9 may lead to increased risks associated with their uses.10 Traditionally community pharmacists would compound special medicines within the pharmacy,11 however overtime, this role has changed. Internationally, community pharmacists have a more patient-focused role themselves12 and in the UK they obtain specials from a specials manufacturer who holds the required license.13

Many guidelines have been created to assist healthcare professionals in safely prescribing, accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines to patients. Donovan et al (2018)14 identified 52 of these guidelines that were in use within the UK during 2017 and analysed them using the Appraisal of Guidelines for REsearch and Evaluation instrument (AGREE) II tool. A lack of consistency was found in the guidelines with varying definitions for what an unlicensed “special” medicine is. Others have also found differing definitions between the General Medical Council (GMC) and the MHRA and it has been suggested that this variation may lead to confusion for healthcare professionals.15

A lack of consistency in the information supplied will inevitably lead to differing levels of understanding across care settings, and a range of perceptions on the acceptability of unlicensed “special” medicines among healthcare professionals, creating challenges for community pharmacists who are the point of contact for supply of specials in the community setting. The limited literature available from within the UK suggested that healthcare professionals have concerns over their legal responsibility when supplying unlicensed “special” medicines in primary care,16 and concerns over their use particularly in children,17 often associated with disruptions in prescribing of further supplies in primary care after patients have been discharged from hospital where the “special” was initiated.18 Studies have also highlighted difficulties for community pharmacy staff when sourcing medicines needed in the community setting.19 The difficulties experienced were reported to lead to increased concerns for patients and carers and suggest a potential for suboptimal patient care for patients requiring unlicensed medicines in community, regardless of whether the unlicensed medicine was initiated in primary or secondary care. Despite this, there are a limited number of studies exploring the experiences of community pharmacy staff with unlicensed medicines, within the UK.20 To the authors’ knowledge, there are no studies solely focussing on exploring healthcare professional views in Wales, where the responsibility for National Health Service (NHS) Wales lies within the Welsh Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Service after devolution, even though almost £4m was spent on “specials” alone in Wales between August 2015 and July 2016 (Dr Mantzourani, email communication, January 3, 2019).

The aim of this study was to explore the views and experiences of community pharmacists and community pharmacy technicians who access and supply unlicensed “special” medicines in Wales and the perceived impact of challenges faced on patient care.

Methods

This study formed the first phase of a mixed methods approach, whereby quantitative methodology would be informed by a qualitative methodology. For the current study, a qualitative phenomenological approach with a constructivist outlook was adopted. This involved face to face semi-structured interviews.

Sample

A pragmatic approach was taken with a combination of convenience and purposive sampling. The sampling frame consisted of eight registered pharmacists and seven registered pharmacy technicians working at one small chain of community pharmacies in South Wales (number of pharmacies = 7). Potential participants were required to have a minimum of 1-year experience working in a community pharmacy. All participants were presumed to be aged 18+ and able to give informed consent due to their profession and registration with the General Pharmaceutical Council, the regulatory body of pharmacy professionals in the UK.

Recruitment

One pharmacist, who worked within the chain of pharmacies sampled, agreed to act as a gatekeeper prior to the start of the study and was involved in disseminating the recruitment materials. Potential participants were identified and contacted by the gatekeeper through email between September and November 2018, and were supplied with the study documentation, consisting of an email invitation, a participant information sheet, and a consent form. All participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any point and were instructed to either contact the gatekeeper to pass along their contact details to the researcher, or to contact the researcher directly. A reminder was sent out by email 2 weeks after the original email invitation had been sent, and again after 2 months. The researcher had no access to identifying information prior to a potential participant getting in touch with them to ask for information for the study.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as the topic is an under-researched area and the method would allow individual participants to raise issues of importance to them, that may not have been previously identified in the available literature. Data collection was conducted between September 2018 and January 2019, interviews were audio-recorded with consent, and transcribed verbatim, with each audio recording deleted immediately after transcription. The interview schedule focused on the processes involved when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines, and the participants’ personal experiences related to this.

Data Analysis

Participants were anonymised during transcriptions and all identifiable information was removed. Inductive thematic analysis was chosen to analyse the interview transcripts, following the method suggested by Braun and Clarke.21 NVivo® software was used to allow the researcher to code the transcripts, retrieve the codes and sort into subthemes and themes. A second researcher reviewed coding and independently assigned themes; any differences in coding were discussed and resolved.

Ethical Considerations

The study was reviewed and gained ethical approval from Cardiff School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Ethics Committee in August 2018 (reference number 1718–28). All participants signed a consent form consenting to the recording of interviews and publication of their responses.

Researcher Characteristics and Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

The researcher collecting data is not a pharmacist, did not personally know any of the participants prior to conducting the interviews and had not experienced receiving an unlicensed “special” medicine, and as such had no predetermined views of what the participants’ experiences should be. The researcher aimed to meet the criteria for trustworthiness as described by Lincoln & Guba (1985),22 and in an effort to increase rigour, transparency and replicability, the structure of the report was based on the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (Supplementary Table 1).23

Results

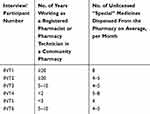

Seven of the 15 potential participants who were invited to participate in the study initially agreed to take part, of which 6 proceeded to complete an interview within the data collection period (response rate 40%). All interviews were conducted face-to-face, taking place in the consultation rooms of the community pharmacies, and lasting between 15 and 40 minutes. Table 1 presents an overview of the participants’ interview number, work experience and the average number of unlicensed “special” medicines dispensed per month at their workplace. Certain demographic information such as occupation, age, sex and the previous work experience of participants are not presented to prevent the possibility of identifying participants from the small sampling frame available. Inductive thematic analysis of transcribed interviews revealed three main themes: requirement for additional patient responsibilities; influences on the confidence felt by pharmacy staff when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines; and continuity of supply (Figure 1). Further examples of representative quotes for each theme can be seen in Supplementary Table 2.

|

Table 1 Overview of Relevant Participant Demographics and Average Monthly Dispensing of Unlicensed Medicines in the Premises |

|

Figure 1 Themes and subthemes identified by thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with community pharmacy staff (pharmacists and registered technicians). |

Theme 1: Requirement for Additional Patient Responsibilities

Participants described how patients receiving unlicensed “special” medicines held additional responsibilities compared to receiving licensed medication. Patient awareness and understanding of the challenges associated with accessing and supplying of specials was perceived as vital in ensuring the patient successfully took on these additional responsibilities, and strategies used as communication tools to improve patient outcomes were highlighted.

Importance of Patient Awareness and Understanding of the Implications of Receiving Unlicensed “Special” Medicines

Patient awareness of the implications of receiving unlicensed “special” medicines was identified as essential in ensuring the increased responsibilities were taken on board consistently by the patients.

[Patients need] an understanding that [unlicensed ‘special’ medicines are] not something that we can just take off the shelf, that, we need a little bit of warning, that we can’t order it in advance without having the prescription … and they need to allow us enough lead time. [INT2]

Clearly explaining issues that patients would need to be aware of was perceived as part of the pharmacy staff role. However, it was noted that a balance was needed between informing the patient about differences between their unlicensed and licensed medicines and reassuring them in relation to potential risks.

I try not to bombard [patients] too much with, a lot of information about what has and hasn’t happened in the past, in terms of testing [for unlicensed ‘special’ medicines] because, you’ve got to get the balance between informing [patients] of what’s going on, but also, not saying too much to kind of worry them and put them off taking it. [INT4]

This balance was required as patients tend to have increased concerns once they have been fully informed about the potentially limited evidence available for unlicensed “special” medicines, occasionally leading to the questioning of the need for the medicine itself.

One of the common discussions I will have [with parents is] well you know, ‘is this really necessary?’ and the other thing is ‘is my child being used as an experiment?’. [INT1]

Patient Initiated Ordering of Further Supplies

Participants reported relying on patients to inform them in advance of when further supplies would be needed and discussed the main reasons why patients were required to continuously initiate ordering within the community.

I think because of the cost of the special we wouldn’t have kept it in [the pharmacy] just in case, especially with it only having a 28-day expiry …. so If we ordered it in advance and then [the patient] didn’t come in for another week or so, then it’s cutting into the expiry of the actual item. [INT3]

The need for patient-led management of the ordering was deemed critical in order to allow enough time for pharmacy staff to obtain the supply and was clearly explained to patients when they initially presented a prescription for an unlicensed medicine to the community pharmacy or when a formulation or dose would change.

Because you know, [unlicensed ‘special’ medicines are] not the run of the mill drugs, you just sit [the patient] down and have a little run through, and also they know that the, the process is different, once, once they’ve had the drug a couple of times they get to know and they will often ring me. [INT1]

Theme 2: Influences on the Confidence Felt by Pharmacy Staff When Accessing and Supplying Unlicensed “Special” Medicines

Participants outlined multiple factors that affected their confidence when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines. The complexity of the medicine itself and the amount of information received with the prescription or medicine led to a decrease in confidence. However, concerns were reduced through the professional trust felt across settings and the participant’s own personal experience within the role.

Ambiguity About Classification and Processing of Unlicensed “Special” Medicines

Varying definitions of the term unlicensed medicines were reported, with some participants describing the lack of license for a particular use and others encompassing the concept of off-label medicines.

[An unlicensed ‘special’ medicine is] something that’s being used away from the product license, meds [sic] that are licensed for one use and then used for different conditions. [INT3]

The wide range and variety of unlicensed “special” medicines available were perceived to add to the complexity and the increased anxiety when processing prescriptions, especially when receiving prescriptions for items that were unusual or unfamiliar to pharmacy staff.

If we’ve only got one patient on [an unlicensed ‘special’ medicine] and I can’t find anything where another patient has been on a dose similar or, or used in that indication then perhaps I might be a little bit more cautious. [INT4]

In these cases, participants highlighted the need to spend time researching the literature on the clinical efficiency of the products, in order to feel confident enough to continue with a prescription.

Information Needs for Safe Transfer of Care Across Settings

A lack of clinical information accompanying new prescriptions for unlicensed “special” medicines was reported and participants explained how they would often need to seek further information across settings before feeling confident enough to complete the clinical checks required. All participants agreed that for new prescriptions they needed to seek further information from the prescriber.

One participant described how providing background clinical information on prescriptions could help to reduce the workload within the pharmacy and increase the confidence felt.

It took a call to the surgery, a call to the hospital and a call to the patient, whereas if I’d had that information with the prescription, ‘this is an unlicensed medicine, the dose has been checked by a kidney specialist, the patient has been on it for years and years’, well, and it goes on, thatwould probably have saved me a bit of time. [INT4]

Professional Trust

Despite the lack of confidence reported above, participants described how the professional trust felt towards manufacturers involved in the supply chain helped to reassure them, and reduce concerns around the use of unlicensed “special” medicines. Trust was also reported towards the clinician who initiated the prescription for an unlicensed “special” medicine, who was perceived to hold specialist knowledge and experience.

If the prescriber [GP] tells me that the consultant or the specialist in a unit somewhere has prescribed [the unlicensed ‘special’ medicine], then that person has expertise in prescribing that kind of drug, in which case, although I might not feel comfortable with it, I wouldn’t go against what somebody says if they’ve got twenty years’ experience in a field. [INT4]

One participant gave an example of how that professional trust of a prescriber in primary care reinforced their own preconceptions about the need to continue the supply of a specific unlicensed medicine.

We’ve had it with the Armour Thyroid, where some surgeries have started to refuse doing that, you know … but they’re basing it on NICE guidance and, health authority guidance, so you know I’m not going to argue with that because, to be honest, I, don’t, think, we should be paying hundreds of pounds for it either …. [INT2]

Association of Confidence with Experience Within the Role

Participants who had more experience within their role reported feeling more confident about their responsibilities when supplying unlicensed “special” medicines and considered it as an integral part of their work activities.

One participant reflected on their own experiences and described how their concerns in relation to unlicensed medicines when first taking on the role of a community pharmacist had decreased, and their confidence had increased over time.

I think when I first qualified, even a one daily [unlicensed ‘special’ medicine] kept me up in the night cause it’s the first time I ever really signed things like that away, but I think in the start when doses were different to what you’d see with licensed items it was a bit, hard to sign it, just purely because no experience, and the worry that something might possibly happen to the patient and that my name is against it ….but as time has gone on, with experience, I know the right calls to make. [INT4]

Theme 3: Continuity of Supply

Participants described how factors such as keeping additional records about the unlicensed medicines supplied and the use of an online ordering system contributed positively to maintaining continuity of supply. However, tensions between care settings and issues with the accessibility and availability of the medicines were still experienced, occasionally resulting in supply delays or even treatment disruption.

Additional Record Keeping

Additional record keeping was described as a requirement before authorising the ordering of an unlicensed medicine, both in the patient medication record but also on a separate file. The recording of all the additional information was perceived as helpful for future re-ordering because it increased transparency.

If it’s something new, then I’m likely to, do it myself first, find out where we get [the unlicensed medicine] from, then we put a note on the patients record so that in future, somebody else could continue the ordering. [INT4]

Participants explained how the additional records kept were also useful when dealing with external queries from pricing bureaus about the cost of the medicines for reimbursement, especially in the case of very expensive items.

Notes were also kept of discussions with patients, so the participants had a record of the patients acknowledging the supply of, and details around, unlicensed medicines.

I confirm with the prescriber and understand the patient knows exactly, what the dose is, the fact that the dose is not licensed, and I usually document that on their records then to say they’ve acknowledged it. [INT4]

Tensions Within and Between Care Settings

Participants described how inaccuracies in selecting the correct product on the GP prescribing software when licensed alternative medicines were suitable, could lead to friction between pharmacy and GP staff, with increased workload while the prescription was corrected and potential for increased costs to the NHS.

I mean we had some last year, with the flu vaccination and two of the [GP] surgeries I think, or it might even have been three of the surgeries, picked the specials liquid for the anti-viral by mistake, instead of the licensed one, which was going to cost an absolute arm and a leg. [INT2]

The inaccurate selection of unlicensed medicines when licensed alternative medicines were suitable, was reported to lead to an increased workload within the pharmacy and delayed supply, while the prescription was corrected.

Examples of differences in the perceived benefit of unlicensed medicines between staff in the same GP surgery were also given, particularly when the responsibility of prescribing moved to a different GP.

We’ve had a few [instances] where historically the GP has prescribed [an unlicensed medicine] and then where the GP that had prescribed it has retired, and then the new GP is going ‘why are we doing this?, I’m not doing this’. [INT2]

Tensions were also mentioned in the interface of primary and secondary care, mainly linked to different acceptability and perceptions of the potential benefit of unlicensed medicine by healthcare professionals across care settings.

In hospitals they’ve got consultants, and consultants have a far wider brief, as regards to prescribing, so they can step outside of certain limitations and when a patient then is transferred to the community, what was ok in a hospital is not necessarily ok with the community GP. [INT1]

Participants explained how the tensions described above can directly impact the continuity of supply, with individual perceptions of acceptability causing disruption in timely access to the medicines.

I have one parent who, the surgery will often have a locum in place, and I understand if the locum doesn’t feel comfortable about signing a repeat prescription for this [unlicensed] drug, but it’s landing that patient’s care … you know suddenly their, perhaps their regular doctor might not be in until the Friday. [INT1]

Challenges with Accessibility and Availability

In addition to different attitudes towards unlicensed medicines, multiple issues were reported with the accessibility and availability of unlicensed “special” medicines. Lack of availability of specific formulations of the unlicensed medicines resulted in disruption of supply and increased workload for the pharmacy staff, who had to change suppliers in order to access the medicine.

The inconsistent availability and varying timelines involved in accessing unlicensed medicines also posed a challenge. An example of manufacturing issues was provided, which led to a sudden increase in the timeline involved when obtaining a specific unlicensed medicine. Pharmacy staff had to adapt the ordering process to ensure continuity of supply. One participant described how the lack of accessibility of a specific medicine from the manufacturer, coinciding with a lack of availability between pharmacies and across care settings, led to treatment disruption for a patient.

Three years ago … we were unable to get the medication in and the patient had a lapse of three days ….in this case, no other pharmacy could supply ….the hospital couldn’t supply after ….and so the patient was without medication for three days, they were monitored and they didn’t suffer adversely, but it’s not a situation that I would ever like to be in. [INT1]

Perceived Advantages of Online Ordering

Most of the participants involved in the study were using the same main supplier for unlicensed medicines, which offered an online ordering system. This option for digital ordering facilitated workload and led to minimal delays, not only as the process did not involve time-consuming phone calls but because it also adopted a “named patient” concept. With this approach, an initial order was linking a specific product with an individual patient, and any subsequent orders were using the same information by default.

The thing about a special, the patient needs it, fairly quickly and what we’ve found with this particular company is they understand that, we can order online, they respond to the order, the details, all the details go on, including the name of the patient ok, we do it as a named patient, it improves tracking ….rather than just give them a number, we do it under a named patient issue [INT1]

One pharmacy had not yet switched over to an online supplier and highlighted the longer process involved when ordering unlicensed “special” medicines.

We’ve got sort of fact sheets that we use for our regular specials, so it’s like a pro forma that we use, we’ll fax that off to the manufacturer, they’ll give us a ring back to confirm it, they’ll then send us an email, with everything in confirming it, letting us know what they expiry date is, pack sizes and if there’s any issues, we’ll then reply to that email confirming it and then it’ll come in, they’ll usually tell us when we’ll be getting it as well [INT2]

The participant was aware of an upcoming change of suppliers and anticipated the use of technology would help streamline the process of ordering and benefits of online tracking.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the views and experiences of community pharmacy staff who access and supply unlicensed “special” medicines in Wales. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in Wales that describes the challenges experienced by pharmacy staff and the resulting adaptations to the workflow that are put in place to optimise patient care. Despite these efforts, the lack of a coherent, consistent, integrated, and transparent pathway between care settings meant issues were still experienced that led to delays and disruption in the continuity of supply.

Participants described varying levels of confidence in their role of accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines. The differing definitions they provided themselves for an unlicensed “special” medicine reflect the wider variation and inconsistencies in the information seen in guidance available to healthcare professionals within the UK. It has been suggested that this lack of consistent information is another contributing factor to the propagation of the risks associated with the use of unlicensed “special” medicines24 and this study further supports the highlighted need for clearer information to be created for healthcare professionals across care settings.25

Transfer of care between settings has been noted by the World Health Organisation as a major area where medication errors occur.26 In response, various initiatives have been developed internationally to improve communication around discharge and minimise the associated risks, as community pharmacists do not traditionally receive information across settings about discharge medicines.27 One of the main challenges reported by participants in this study, was the lack of accompanying clinical information provided with prescriptions initiating therapy with an unlicensed medicine in primary care or continuing with a therapy introduced in secondary care, explaining how they often needed to seek further information from a range of resources about the medicine before feeling confident enough to proceed with the supply. This was usually accompanied by keeping additional records compared to licensed medicines not only as a legal requirement1 but also as a means of increasing transparency within the workplace and across care settings, as well as for documenting their professional judgement as discussed in guidance by the professional (Royal Pharmaceutical Society) and regulatory (General Pharmaceutical Council) bodies for pharmacists in the UK.28,29

In Wales transfer of care between hospital and community is facilitated by the national community pharmacy Discharge Medicines Review Service introduced in 2013 and rolled out nationally in 2015.30 The DMR service has been shown to be associated with decreased hospital readmissions,31 its value further reinforced by Welsh Government in its response to a global pandemic by being the only advanced service maintained in community pharmacies.32 Despite this, and even though the need for clinical information to be made accessible for community pharmacists has been recognised in the literature and seen as a method of improving continuity after discharge,33 the DMR and other such schemes do not usually provide clinical reasons for medication changes during a patient’s in-hospital stay. Additionally, many unlicensed medicines are initiated in secondary care by specialist consultants in outpatient clinics, with no established pathway to communicate clinical reasoning to the follow-up prescriber and community pharmacist in primary care. Participants reported feeling reassured from the perceived specialist knowledge and experience of the hospital prescriber, and this trust reduced their concerns and increased their confidence to proceed with the supply, similarly to outcomes reported elsewhere in the literature.34 Professional trust is vital when working as part of a team with improved patient outcomes as a goal. However, and despite evidence to suggest community pharmacy staff can play a crucial role in assisting patients during care transfers,35 and that allowing community pharmacists insight of and input into full patient records would enable them to make informed decisions and increase patient safety (Pharmaceutical journal 2019),36 the exchange of clinical information between GPs and community pharmacists is reported in the literature as suboptimal.37

Integrated care pathways, outlining the patient journey and detailing what should happen at each step during treatment, have been in use in the UK for a range of different conditions.38 Used as a means to improve consistency and patient experience, care pathways have been found to be beneficial in improving clinical outcomes,39 interprofessional teamwork40 and in providing a basis for recommendations to improve services.41 A lack of an established care pathway for unlicensed medicines was shown in this study to impact on the perceived responsibility of key stakeholders, with prescribing clinicians in secondary care transferring the responsibility for further prescribing and supplies to the general practitioner and community pharmacist to share.42

Participants discussed how different awareness levels around, and perceptions of this responsibility, often led to delays or disruptions of the continuity of supply, for example, with GPs unintentionally prescribing unlicensed medicines or refusing to prescribe the unlicensed medicine required. This has been reported previously in the UK with GPs giving costs, lack of available evidence, or personal inexperience, as reasons to refuse to continue prescriptions for unlicensed medicines.18 Organisations such as the international foundation for integrated care have been developed that provide an education network with a focus on integrated care and aims to improve patient care by sharing the perspectives of those throughout the different healthcare settings.43 The issues around transmural care (ie where primary and secondary care interact) identified in this study and described above provide further evidence to support that an establish care pathway, integrating a short, standardised template with key clinical information to accompany each prescription from one setting to another, as suggested by one participant, would help to reduce the workload within the pharmacy and the GP surgeries when dealing with unlicensed medication, increase the confidence felt by primary care staff and ultimately improve patient safety. The previous and repeated individual experience was found to be associated with increased levels of confidence when supplying an unlicensed medicine in this study, in line with literature reporting how community pharmacists build their understanding of unlicensed and off-label medicines through their experiences within their role.44 This experience is usually built post registration, as Undergraduate pharmacy curricula do not traditionally include guidance on how to use unlicensed medicines as an explicit clinical topic due to its complexity.45 In the USA, the national Association of Speciality Pharmacy offers continued education for healthcare professionals around speciality pharmacies and speciality medications.46 No similar body exists in the UK. However, structured and targeted support for continuous professional development on unlicensed medicines provided by existing national institutions such as Health Education England (HEE) and Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW) can ensure consistency of information and lead to increased levels of confidence for all pharmacy staff.

Another key concept that was discussed by participants was the additional responsibility that patients receiving unlicensed medicines were required to take compared to patients on traditional medicines, an issue of concern considering that it has been suggested the general public in the UK have little awareness of the use of unlicensed “special” medicines.47 Varying timelines required to access the medicines, inconsistent bioequivalence in the products available and short expiry dates preventing automatic stock re-ordering were some of the issues highlighted by the participants and reported previously in the literature.19,48,49 This led to an increased need to negotiate shared goals with the patient as part of a patient-centred approach, with patients needing to maintain and manage communication across settings and often to take responsibility for initiating the ordering of further supplies, critical to ensure the best possible outcomes.50,51 The resulting increased involvement of patients in their care had to be achieved by maintaining the balance of providing additional information about unlicensed “special” medicines without causing concern. Participants gave examples of concerns raised by patients consistent with that in the literature, showing increased concern once fully informed about the use of unlicensed medicines,19,52,53 one participant explained how parents often questioned the need for the unlicensed medicine prescribed for their child, suggesting that the concerns and perceptions highlighted may lead to non-adherent behaviours.54,55 Literature reports the successful use of a range of educational interventions to increase patient awareness on medication use for different conditions.56,57 Development of such educational interventions, with patient input to ensure they meet the needs of the end-user,58 can be one way of informing patients about the uses and implications of receiving an unlicensed “special” medicine without causing concerns. Patients may benefit from the development of a common resource for information, for example, a booklet explaining what unlicensed “special” medicines are and providing some background using patient-tailored language. These have been produced locally within the UK59 but have not been standardised for more widely adopted use.

One aspect participants in this study identified in improving the continuity of supply was the use of the online ordering system. Participants described how this technology helped to reduce the workload when ordering unlicensed “special” medicines and allowed for better communication between care settings, supporting even further the examples in the literature of how technology can be successfully integrated into community pharmacy practice,60 with resulting benefits on patient care.61,62 Despite this, some participants were still using outdated forms of technology such as fax machines to place orders to suppliers, even though they have been linked to increasing security risks and expenses within community pharmacy.63 The results of this study suggest that community pharmacies may benefit from using an online ordering system and upgrading technological equipment where practical.

The department of health and social care (2019)64 has highlighted the issues associated with cost when accessing unlicensed “special” medicines. One option for their supply is directly from the hospital setting in which they are initiated, or from an NHS approved supplier. Some countries have responded to challenges associated with the increasing cost of external manufacturing of specials by introducing small-scale manufacturing by pharmacy departments in hospitals, on a patient named basis.65–67 A study conducted within the UK explored the impact of having unlicensed “special” medicines supplied directly by the hospital to children in the community, and showed a significant reduction in cost.68 When unlicensed “special” medicines cannot continue to be supplied directly by the hospital, commercial suppliers can charge higher fees/prices to cover the one-off formulations and production in their facilities, as they are not made on a commercial scale,69 and any post-production quality assurance testing. If the medicine is listed in the relevant Part VIIIB section of the Drug Tariff, then a pre-set price will be reimbursed to community pharmacy by the NHS.70 However, many unlicensed “special” medicines are not listed in the drug tariff, allowing suppliers to set their own prices for these medicines, leading to huge variations. Lack of prescribers’ awareness of these substantial costs and of cheaper alternatives was reported in this study, suggesting an unnecessary burden on healthcare costs that can be targeted for a more efficient system. The department of health and social care (2019) suggested a central service that would supply all specials that are not included in Part VIIIB of the Drug Tariff, and further work is underway to explore requirements for this mechanism.64

Limitations

The sample used in the study only involved a small number of participants working in one small chain of pharmacies in South Wales and therefore results may not be generalisable across all community pharmacies. However, the results offer an insight into the views and experiences some community pharmacy staff face when accessing and supplying unlicensed “special” medicines in Wales and form the base for developing a survey to be used in future research.

Future Work

Some topics were not raised by the participants in this study, such as the process and experiences related to importing unlicensed “special” medicines into the UK, and the similarities and differences between the views and perceptions of staff in different pharmacy settings such as independent, smaller and larger national chains.

The results of this study will be used alongside existing literature and stakeholder input to create a survey that will be disseminated to a wider sample of community pharmacy staff across Wales. This project is also part of a larger study not only exploring the views and experiences of community pharmacy staff but also primary and secondary care clinicians who prescribe, and patients who receive, unlicensed “special” medicines.

Conclusion

This study identified several factors that impact on pharmacy staff supporting patients receiving unlicensed medicines throughout their journey, from initial prescribing to continuing supply. Results suggest that an integrated, transparent care pathway that follows the patient across all care settings will result in reduced clinical risk and logistical problems associated with the transfer of care. Tailored support mechanisms for patients and healthcare professionals may provide further reassurance to the former and increase the confidence of the later, so a patient-centred approach can be adopted at all times. Further research on exploring the option of a hospital or centralised NHS-led supply may also be crucial to shaping a national strategy for reducing unnecessary costs often associated with supplies of unlicensed medicines.

Disclosure

SR, AJ, JPS and SH are representatives of organisations who contributed to the funding of this work as part of a PhD studentship (SR, Mayberry Pharmacy; JPS, SH and AJ, SMPU) . They engaged as key stakeholders in the conceptualisation of the project and development of the methodology . They had no influence on data analysis and interpretation, which was led by EM, AW and RY. AW reports grants, personal fees, non-financial support from Cardiff University, grants from Welsh European Funding Office, St Mary’s Pharmaceutical Unit, and Mayberry pharmacy, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Human medicines regulations 2012. Pharm J. 2012;289(7719–7720):200.

2. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The supply of unlicensed medicinal products (‘specials’). Guidance note 14. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/373505/The_supply_of_unlicensed_medicinal_products__specials_.pdf.

3. Hilmer SN, Gazarian M. Clinical pharmacology in special populations: the extremes of age. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2008;1(4):467–469. doi:10.1586/17512433.1.4.467

4. Limb L, Nutt S, Sen A. Experiences of rare diseases: an insight from patients and families. Rare Dis UK. 2010.

5. Dani KA, Murray LJ, Razvi S. Rare neurological diseases: a practical approach to management. Pract Neurol. 2013;13(4):219–227. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2012-000379

6. Wright DJ, Smithard DG, Griffith R. Optimising medicines administration for patients with dysphagia in hospital: medical or nursing responsibility? Geriatrics. 2020;5(1):9. doi:10.3390/geriatrics5010009

7. PSNC Main site. Medicine shortages; 2020. Available from: <https://psnc.org.uk/dispensing-supply/supply-chain/medicine-shortages/>.

8. Prescribing specials guidance for the prescribers of specials. Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2016. Available from: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Support/toolkit/professional-standards—prescribing-specials.pdf.

9. Bourns IM. Unlicensed medicines in the UK-legal frameworks, risks, and their management. Med Access Point Care. 2017;1:maapoc–0000006. doi:10.5301/maapoc.0000006

10. Sutherland A, Waldek S. It is time to review how unlicensed medicines are used. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(9):1029–1035. doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1886-z

11. Tucker R. The evolving role of community pharmacists. Br J Fam Med. 2018.

12. Wiedenmayer K, Summers RS, Mackie CA, Gous AG, Everard M, Tromp D, World Health Organization. Developing Pharmacy Practice: A Focus on Patient Care: Handbook (No. WHO/PSM/PAR/2006.5). World Health Organization; 2006.

13. The Human Medicines Regulations. Legislation.gov.uk.; 2012. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/contents/made.

14. Donovan G, Parkin L, Brierley‐Jones L, Wilkes S. Unlicensed medicines use: a UK guideline analysis using AGREE II. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(6):515–525. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12436

15. Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Unlicensed and off-label uses of medicines: definitions and clarification of terminology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(12):2615–2625. doi:10.1111/bcp.13394

16. Chisholm A. Exploring UK attitudes towards unlicensed medicines use: a questionnaire-based study of members of the general public and physicians. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:27–40. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S28341

17. Mukattash T, Hawwa AF, Trew K, McElnay JC. Healthcare professional experiences and attitudes on unlicensed/off-label paediatric prescribing and paediatric clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(5):449–461. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0978-z

18. Wong ICK, Basra N, Yeung VW, Cope J. Supply problems of unlicensed and off-label medicines after discharge. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(8):686–688. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.093724

19. Husain NR, Davies JG, Tomlin S. Supply of unlicensed medicines to children: semi-structured interviews with carers. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1):1–5. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000051

20. Donovan G, Parkin L, Wilkes S. Special unlicensed medicines: what we do and do not know about them. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(641):e861–e863. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X688033

21. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

22. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Establishing trustworthiness. Naturalistic Inq. 1985;289(331):289–327.

23. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

24. Donovan G, Parkin L, Brierley-Jones L, Benson A, Wilkes S. Exploring Multidisciplinary Use of Unlicensed Medicines Across Primary and Secondary Care (EMULSION). 2016.

25. Donovan G, Parkin L, Brierley-Jones L, Wilkes S. Use of unlicensed medicines by prescribers, pharmacists and patients across primary and secondary care: a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(S3):9.

26. Medication Safety in Transitions of Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. (WHO/UHC/SDS/2019.9). Available from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/medication-safety/TransitionOfCare.pdf?ua=1.

27. Wilcock M, Bearman D. Community pharmacist management of discharge medication summaries in primary care. Drug Ther Bull. 2019;57(12):179–180. doi:10.1136/dtb.2019.000052

28. RPS. Advice: professional judgement. Pharm J. 2013;290:272.

29. Council, GP. Standards for pharmacy professionals. London, UK: General Pharmaceutical Council; 2017. Available from: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017.pdf.

30. Hodson K, Blenkinsopp A, Cohen D, et al. Evaluation of the Discharge Medicines Review Service. Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care, University of South Wales;March 2014.

31. Mantzourani E, Nazar H, Phibben C, et al. Exploring the association of the discharge medicines review with patient hospital readmissions through national routine data linkage in Wales: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e033551. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033551

32. Welsh Government. 2020. Available from: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-03/coronavirus-covid-19-important-information-for-community-pharmacies.pdf.

33. Urban R, Paloumpi E, Rana N, Morgan J. Communicating medication changes to community pharmacy post-discharge: the good, the bad, and the improvements. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):813–820. doi:10.1007/s11096-013-9813-9

34. Frankel GEC, Austin Z. Responsibility and confidence: identifying barriers to advanced pharmacy practice. Can Pharm J. 2013;146(3):155–161. doi:10.1177/1715163513487309

35. Kooyman CD, Witry MJ. The developing role of community pharmacists in facilitating care transitions: a systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2019;59(2):265–274. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.11.009

36. Pharmacy access to full patient records is more critical than ever. Pharm J. 2019;303.

37. Hindi AM, Jacobs S, Schafheutle EI. Solidarity or dissonance? A systematic review of pharmacist and GP views on community pharmacy services in the UK. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(3):565–598. doi:10.1111/hsc.12618

38. Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ. 1998;316(7125):133–137. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7125.133

39. National Council for the Professional Development of Nursing and Midwifery. Improving the patient journey: understanding integrated care pathways. NCPNW. 2006.

40. Scaria MK. Role of care pathways in interprofessional teamwork. Nurs Stand. 2016;30(52):42–47. doi:10.7748/ns.2016.e10402

41. Baron S. Evaluating the patient journey approach to ensure health care is centred on patients. Nurs Times. 2009;105(22):20–23.

42. Professional guidance for the procurement and supply of specials. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. RPS; 2015. Available from: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Support/toolkit/specials-professional-guidance.pdf.

43. The International Foundation For Integrated Care. IFIC; 2020. Available from: https://integratedcarefoundation.org/.

44. Stewart D, Rouf A, Snaith A, Elliott K, Helms PJ, McLay JS. Attitudes and experiences of community pharmacists towards paediatric off‐label prescribing: a prospective survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(1):90–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02865.x

45. Future pharmacists standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists. General Pharmaceutical Council; 2011. [Pharmacyregulation.org. online]. Available from: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/future_pharmacists_standards_for_the_initial_education_and_training_of_pharmacists.pdf.

46. National Association Of Specialty Pharmacy. NASP. Naspnet.org. Available from: https://naspnet.org/#/ms-1/2.

47. Mukattash TL, Millership JS, Collier PS, McElnay JC. Public awareness and views on unlicensed use of medicines in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(6):838–845. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03290.x

48. Rawlence E, Lowey A, Tomlin S, Auyeung V. Is the provision of paediatric oral liquid unlicensed medicines safe? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract. 2018;103(6):310–313.

49. Venables R, Stirling H, Batchelor H, Marriott J. Problems with oral formulations prescribed to children: a focus group study of healthcare professionals. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1057–1067. doi:10.1007/s11096-015-0152-x

50. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. World Health Organization; 2015. (No. WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/155002/WHO_HIS_SDS_2015.6_eng.pdf;jsessionid=1122F886E1576D316194CD13750C10BD?sequence=1.

51. Kane PM, Murtagh FEM, Ryan K, et al. The gap between policy and practice: a systematic review of patient-centred care interventions in chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(6):673–687. doi:10.1007/s10741-015-9508-5

52. Mukattash TL, Jarab AS, Daradkeh A, Abufarha R, AbuHammad SH, AlRabadi NN. Parental views and attitudes towards use of unlicensed and off‐label medicines in children and paediatric clinical trials: an online cross‐sectional study in the Arab world. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2019;10(3):333–339.

53. Aston J, Wilson KA, Terry DR. The treatment-related experiences of parents, children and young people with regular prescribed medication. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(1):113–121. doi:10.1007/s11096-018-0756-z

54. Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity–concerns framework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):41–46. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004

55. Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):80633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080633

56. Nicolson DJ, Knapp P, Raynor DK, Spoor P. Written information about individual medicines for consumers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002104.pub3.

57. Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Howell M, Craig JC. Educational interventions for patients with CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):353–370. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.022

58. NHS Gaining insights from/working in partnership with health service users. NHS Improvement; 2018. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2138/partnership-working-health-service-users.pdf.

59. Unlicensed and “off-label” medicines. information for patients, parents and carers; 2014. Ouh.nhs.uk. Available from: https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/12048Punlicensed.pdf.

60. Goundrey-Smith S. Examining the role of new technology in pharmacy: now and in the future. Pharm J. 2014;292(11):10–1211.

61. Petrakaki D, Cornford T, Hibberd R, Lichtner V, Barber N. The role of technology in shaping the professional future of community pharmacists: the case of the electronic prescription service in the english national health service. In: Researching the Future in Information Systems. Vol. 356. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2011:179–195.

62. Mantzourani E, Way CM, Hodson KL. Does an integrated information technology system provide support for community pharmacists undertaking discharge medicines reviews? An exploratory study. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:145. doi:10.2147/IPRP.S133273

63. Implementing online fax technology in the pharmacy. Pharm J. 2017.

64. Community pharmacy drug reimbursement reforms consultation. Department of Health and Social Care; 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/819801/community-pharmacy-reimbursement-consultation-document.pdf.

65. Stokel-Walker C. DIY drugs: should hospitals make their own medicine? [online]. The Guardian. 2019. Available from: <https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/oct/15/diy-drugs-should-hospitals-make-their-own-medicine>.

66. Pascoe R. Dutch hospital challenges big pharma by making own version of very pricey drug. [online]. Dutchnews.Nl. 2018. Available from: <https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2018/04/dutch-hospital-challenges-big-pharma-by-making-own-version-of-very-pricey-drug/>.

67. Abelson R, Thomas K. Fed up with drug companies, hospitals decide to start their own. [online]. Nytimes.com. 2018. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/health/drug-prices-hospitals.html.

68. Terry DRP, Sinclair AG, Ubhi H, Wilson KA, DasGupta M. Cost benefit of hospital led supplies of unlicensed medicines for children at home. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(5):e15–e15. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-301728.31

69. Griffith R. Unlicensed medicines. Br J Nurs. 2019;28(17):1154–1155. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.17.1154

70. Chaplin S. How drug tariff specials have reduced prescribing costs. Prescriber. 2014;25(5):27–29.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.