Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

Typology of end-of-life priorities in Saudi females: averaging analysis and Q-methodology

Authors Hammami M , Hammami S, Amer H, Khodr N

Received 2 February 2016

Accepted for publication 17 March 2016

Published 17 May 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 781—794

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S105578

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Muhammad M Hammami,1,2 Safa Hammami,1 Hala A Amer,1 Nesrine A Khodr1

1Clinical Studies and Empirical Ethics Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, 2College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Background: Understanding culture-and sex-related end-of-life preferences is essential to provide quality end-of-life care. We have previously explored end-of-life choices in Saudi males and found important culture-related differences and that Q-methodology is useful in identifying intraculture, opinion-based groups. Here, we explore Saudi females’ end-of-life choices.

Methods: A volunteer sample of 68 females rank-ordered 47 opinion statements on end-of-life issues into a nine-category symmetrical distribution. The ranking scores of the statements were analyzed by averaging analysis and Q-methodology.

Results: The mean age of the females in the sample was 30.3 years (range, 19–55 years). Among them, 51% reported average religiosity, 78% reported very good health, 79% reported very good life quality, and 100% reported high-school education or more. The extreme five overall priorities were to be able to say the statement of faith, be at peace with God, die without having the body exposed, maintain dignity, and resolve all conflicts. The extreme five overall dis-priorities were to die in the hospital, die well dressed, be informed about impending death by family/friends rather than doctor, die at peak of life, and not know if one has a fatal illness. Q-methodology identified five opinion-based groups with qualitatively different characteristics: “physical and emotional privacy concerned, family caring” (younger, lower religiosity), “whole person” (higher religiosity), “pain and informational privacy concerned” (lower life quality), “decisional privacy concerned” (older, higher life quality), and “life quantity concerned, family dependent” (high life quality, low life satisfaction). Out of the extreme 14 priorities/dis-priorities for each group, 21%–50% were not represented among the extreme 20 priorities/dis-priorities for the entire sample.

Conclusion: Consistent with the previously reported findings in Saudi males, transcendence and dying in the hospital were the extreme end-of-life priority and dis-priority, respectively, in Saudi females. Body modesty was a major overall concern; however, concerns about pain, various types of privacy, and life quantity were variably emphasized by the five opinion-based groups but masked by averaging analysis.

Keywords: end-of-life priorities, end-of-life dis-priorities, Q-methodology, score-averaging, Muslims, Saudi females

Background

Good death has been defined as one that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients and their families, in accordance with the patients’ and families’ wishes, and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards.1 End of life has been associated with unnecessary suffering1,2 and continues to be a global public health problem and health systems problem.3–5

Several studies have explored the general public’s end-of-life priorities in Western6–10 and other countries11–13 and showed important culture-related divergences. Most studies used independent rating of choices and analyzed the results by averaging across individuals, which tend to attribute maximum importance to a large number of choices14 and obscure individual priority structures.15 Exploratory factor analysis revealed that four latent domains underlie the Quality of Dying and Death instrument.16 Q-methodology is a special type of factor analysis that groups respondents based on the similarity of their rank-ordering of opinion statements.17,18 We have recently studied the usefulness of the Q-methodology in exploring Saudi males’ end-of-life choices and found that transcendence and dying in the hospital were the extreme priority and dis-priority, respectively, that there is less emphasis on the physiological aspects of life quality, and that averaging analysis may mask important priorities and dis-priorities that can be revealed by Q-methodology.15

The aims of this study were to explore Saudi females’ end-of-life choices, using averaging analysis and Q-methodology, and compare them to previously reported Saudi males’ choices.

Methods

This study was part of an exploratory cross-sectional study15 that was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki after approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSH&RC). All respondents provided verbal informed consent. The Research Ethics Committee waived the requirement of written consent because the study doesn’t present more than minimal risk and doesn’t involve any procedures for which written consent is normally required outside research consent, and to further protect confidentiality as the consent document would be the only identifiable link between the respondents and the study.

Study instrument

The development and validation of the study instrument (Q-set) have been reported previously.15 The instrument was constructed based on published conceptual frameworks19,20 and instruments, including the Preference About Dying and Death questionnaire,14,21 the Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire,16,22,23 and PRISMA (positive diversities of European priorities for research and measurement in end-of-life care) European survey questionnaire,7–12 as well as related Islamic literature. Q-sorting requires respondents to arrange statements according to their subjective relative importance into graded priority and dis-priority, using a symmetric forced distribution (sorting sheet). The sorting sheet for this study had nine categories (1= extreme dis-priority, 5= nonpriority, 9= extreme priority) with symmetrically distributed number of slots under each category: categories 1 and 9, three slots each; categories 2 and 8, four slots each; categories 3 and 7, six slots each; and categories 4, 5, and 6, seven slots each. The Q-set has 47 end-of-life opinion statements distributed in eight thematic domains: symptoms and personal control (n=7), treatment preferences (n=5), whole-person concerns (n=8), moment of death (n=5), family/friends (n=6), achieving sense of completion/spirituality/religiosity (n=5), preparation for death (n=5), and relationship with health care professionals (n=6). The first three domains are most related to life quality vs quantity concerns, the fourth and fifth to connectedness, the sixth to transcendence, the seventh to coping, and the eighth to information disclosure and decision making (Supplementary material).

Respondents were observed while Q-sorting and were requested to comment on their extreme choices after completing the Q-sort. Time spent and Q-sort completeness (ie, each statement is sorted only once) were checked, and respondents were asked to correct identified mistakes.

The following data were also collected: age, sorting time, self-declared religiosity (compared to Muslims in Saudi Arabia; 5-point scale, much less =1 to much more =5), general health (5-point scale, excellent =1 to poor =5), life quality (4-point scale, excellent =1 to fair =4), employment status (student, employed, self-employed, not employed, housewife), living arrangement (with spouse, with parents, with children, with other family members, alone), and death experience in family/close friends (last year, last 5 years, none in last 5 years).

Volunteer sample

KFSH&RC Saudi employees, patients, and patients’ companions attending outpatient clinics were invited to participate through direct contact and advertisement. Eligibility criteria included Saudi nationality, age ≥18 years, high school education or more, and ability to understand study purpose and procedures. The original study recruited both males and females; however, due to limitation of the Q-methodology software program and the fact that analyzing mixed male and female Q-sorts obscured important sex differences, males’ results were reported separately.15

Analysis

Data were verified by double entry and validity checks. Q-sorts were analyzed by by-person centroid factor analysis (Q-methodology analysis), using PCQ for Windows (PCQ Software, Portland, OR, USA). Data analysis in Q-methodology involves sequential application of correlation, factor analysis, and computation of factor scores. Centroids were extracted and then subjected to Varimax rotation to mathematically find a solution for which each Q-sort (respondent) has large loading, preferably on one factor (factor loading indicates the strength of respondent’s association with the identified factor or opinion type). In order to facilitate factor interpretation, some factors were, in addition, judgmentally rotated to minimize negative loading. Q-sorts with loading in excess of 0.38 (P<0.01) on one, and only one, factor were considered definer Q-sorts. A model Q-sort for each factor was composed from statements’ scores calculated as weighted (based on factor loading) average across definer Q-sorts. This idealized Q-sort represented how a hypothesized respondent with 100% loading on the factor would have ordered all the Q-set statements. Interpretation of factors involved comparing composite statement scores across factors and reviewing respondents’ postsorting comments. Respondents whose Q-sorts loaded significantly were compared as groups with regard to their age, sorting time, religiosity, general health, life quality, attitude to death, and life satisfaction. The z-test was used to compare mean ranking scores of individual statement between males (previously reported) and females; combined standard error was calculated as the square root of the sum of squares of the separate standard errors.24 Two-tailed P-values are reported.

Results

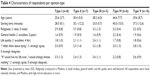

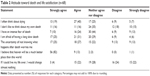

All 68 Q-sorts were evaluable. Mean (SD) sorting time was 35.1 minutes (13.7 minutes). Respondents’ demographics are presented in Table 1. Their attitude toward death and degree of life satisfaction is summarized in Table 2.

| Table 2 Attitude toward death and life satisfaction (n=68) |

Averaging analysis

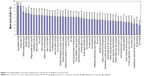

Mean (SD) ranking scores of the 47 statements are shown in Figure 1. We arbitrarily considered the ten statements with the highest mean scores as priorities, the ten with the lowest mean scores as dis-priorities, and the remaining 27 as nonpriorities.

Priorities

Four of the statements that received priority scores were in the transcendence domain, “I want to die being able to say the statement of faith” (mean [SD], 8.6 [1.0]), “I want to die at peace with God” (8.5 [0.9]), “I want to resolve any conflict before I die” (6.3 [2.0]), and “I want my religious death rituals to be respected” (6.0 [1.9]); five were related to life quality/quantity, “I want to die without having my body exposed” (6.9 [1.6]), “I want to die maintaining my dignity” (6.4 [1.7]), “I want to die being able to bathe and feed myself” (5.8 [1.9]), “I want to die free of pain” (5.8 [2.0]), and “I want to die being able to control my bowels” (5.8 [2.0]); and one was in the moment of death domain, “I want to have my family/friends with me at my last moments” (5.9 [2.0]).

Dis-priorities

One of the statements that received dis-priority score was in the moment of death domain, “I want to die in hospital” (2.8 [1.7]); five were related to life quality/quantity, “I want to die well dressed” (3.2 [2.1]), “I want to die at the peak of my life” (3.4 [2.2]), “I want to live longer regardless of my medical condition” (3.7 [2.2]), “If I go into coma, I do not want to be placed in an intensive care unit” (3.9 [1.6]), and “I want to receive medical care with compassion” (4.0 [2.0]); two were in the family/friends domain, “I want my family/friends, rather than my doctor to inform me about my impending death” (3.3 [1.5]) and “I want my doctor to discuss any concern relating to my illness and care in the presence of my family” (3.7 [1.8]); one was in the preparation for death domain, “If I have a fatal illness, I don’t want to know” (3.7 [2.0]); and one was in the transcendence domain, “I want to avoid being a financial burden to my society” (3.9 [1.5]).

Factor analysis

We were able to extract nine factors with eigenvalues >1. However, based on inspection of the scree plot (graphs eigenvalues against number of extracted factors) and logical analysis of the results, we determined that the practically appropriate number of factors to extract is 5. The five factors (opinion types) accounted for 45% of the total variance and 62% of the 68 Q-sorts. Of the remaining Q-sorts, ten did not have significant loading on any of the five factors and 16 were confounded (loaded significantly on more than one factor).

Consensus statements

There were five consensus statements. All opinion types assigned similar priority scores to “I want to die at peace with God” (rounded scores 9), “I want to die being able to say the statement of faith (shahadah)” (rounded scores 8–9), and “I want to resolve any conflict before I die” (rounded scores 6–7). Respondents’ justifications included, “The most important thing is to be at peace with God to enter paradise”, “Life is a pathway, God satisfaction is most important”, “I am always anxious because I feel that I am not righteous enough”, “This is what we have been created for”, and “It is the sign that I was successful in this life” for the first statement; “Human beings make mistakes; saying the statement of faith and asking for forgiveness is very important”, “It is the key to paradise”, “I wish I can, they say those who are worthy will be able to say it”, “So that those around me will be assured, which will make it easier for them when I leave”, and citing Prophet Muhammad’s saying “He, whose last words are: there is no God but Allah will enter Paradise” for the second statement; and “I want to die with peace of mind with no one having a right on me”, “So that there will be no conflict after my death”, and “So people will remember me in a good way” for the third statement. In addition, all opinion types assigned similar dis-priority scores to two statements, “I want to die in the hospital” (rounded scores 1–2) and “I want my family/friends, rather than my doctor to inform me about my impending death” (rounded scores 2–3). Justifications included, “Because I hate hospital and know doctors play with patients and experiment on them”, “So that I don’t suffer during my death”, “The important thing is that my family will be with me”, and “I want to die in my home, self-dependent” for the first statement and “I want to prepare them for the news” and “So that they do not suffer unnecessarily” for the second.

Differentiating statement

There was only one differentiating statement, “I want to die without having my body exposed”. It differentiated opinion type III from the rest (rounded scores 4 vs 8–9, respectively). Justifications for giving priority scores included, “I don’t want to reach that sad disrespectful state”, “As a female, this is very important to me even when I am unconscious”, and “God ordered that”.

We arbitrarily considered that a statement represented an issue important to respondents belonging to a particular opinion type if it received one of the seven highest (priority) or seven lowest (dis-priority) mean scores (corresponding to the two extreme categories in the sorting sheet, bilaterally). The rest of the statements were considered to represent nonpriority issues. All the five opinion types were highly transcendent. Privacy, whether physical, emotional, informational, or decisional, was an important differentiating issue among the five opinion types, along with attitudes toward family (family caring, family dependent), pain, and life quantity (Table 3).

| Table 3 Opinion types identified by by-person factor analysis |

Opinion type I (physical and emotional privacy concerned, family caring)

The eigenvalue and explained variance of opinion type I were 7.7% and 11%, respectively. Eight respondents belonged to this opinion type only, and eight belonged both to this and other opinion types.

Opinion type I was life quality concerned, more specifically physical and emotional privacy concerned. First, it assigned dis-priority scores to “I want to live longer regardless of my medical condition” and “I want to receive all available treatments no matter what the chances of success are”. Second, in addition to assigning a priority score to “I want to die without having my body exposed”, it assigned priority scores to “I want to die being able to control my bladder”, “I want to die being able to control my bowels”, and “I want to die being able to bathe and feed myself”. Third, it gave the most extreme dis-priority score to “I want to discuss my fears about dying with my physician” and a dis-priority score to “I want to receive medical care with compassion”. Justifications included, “I don’t trust doctors; they don’t care about their patient’s emotions”, “What would compassion give me? Nothing at all”, and “I don’t want compassion and mercy from anyone”. Consistent with its physical and emotional privacy inclination and in variance with the other four opinion types, having an Islamic clergy at the time of death was a dis-priority for opinion type I. Justifications included, “I don’t need that, what I know about my religion is adequate. I just need to remember God in my own way” and “I feel nervous if there is a clergy with me”.

Opinion type I was described as family caring because, in addition to assigning a dis-priority score to “I want my family/friends rather than my doctor to inform me about my impending death”, it assigned a priority score to “I want to die knowing that my family/friends are prepared to accept my death”. Justifications included, “My mother is very much connected to me, I don’t think she will accept my death easily”, “I would like to prepare them even if partially so”, “I don’t want to be a cause of their suffering after my death”, and “I will be relieved if they are not crying or saddened due to my departure”. Furthermore, a respondent in this group justified giving a priority score to “I want to die at the peak of my life” by “So that I will not be a burden on my family”, and another respondent justified giving a dis-priority score to “I want to live longer regardless of my medical condition” by “I will torture myself and my family without benefit”.

Two priorities (being able to control bladder and having family/friends prepared to accept death) and three dis-priorities (discussing dying fears with physician, receiving all available treatment regardless of the chances of success, and having an Islamic clergy at the last moments) for this opinion type were not among the ten priorities and ten dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample.

Opinion type II (whole person)

The eigenvalue and explained variance of opinion type II were 5.6% and 8%, respectively. Seven respondents belonged to this opinion type only, and seven belonged both to this and other opinion types.

Opinion type II had a whole-person concern. In addition to embracing “I want to die without having my body exposed”, it embraced “I want to die being able to control my bowels”, “I want to die being able to communicate with others”, “I want to die maintaining my dignity”, and “I want to have my financial affairs in order before I die”, stressing different aspects of life quality. On the other hand, it opposed, “I want to die free of depression”, “I want to die well dressed”, “I want to avoid being a financial burden to my society”, “I want to have no tubes inserted into my body”, and “I want to die instantaneously”, suggesting a concern for life quantity as well. Justifications included, “What is important to me is how effective the treatment is, not what it is or how it is done” and “Sickness and suffering before death are among the causes of God forgiveness of sins”.

Two priorities (being able to communicate and having financial affairs in order) and four dis-priorities (dying free of depression, discussing dying fears with physician, having no tubes inserted into the body, and dying instantaneously) for this opinion type were not among the ten priorities and ten dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample.

Opinion type III (pain and informational privacy concerned)

The eigenvalue and explained variance of opinion type III were 4.6% and 7%, respectively. Five respondents belonged to this opinion type only, and four belonged both to this and other opinion types.

Opinion type III was clearly life quality concerned, particularly, regarding pain and informational privacy. It gave the most extreme priority score to “I want to die free of pain”. Justifications included, “I believe pain is what scares humans the most, I fear it” and “If I am in pain I would not be able to communicate with my family/friends, they will only remember my pain, and my cheerful image will be lost”. It also gave priority score to “I want to die maintaining my dignity”, “I want to have my financial affairs in order before I die”, and “I want to die being able to communicate with others”. Concerns about informational privacy were inferred from embracing, “I want the doctor to inform me about my impending death before informing my family”, and opposing, “I want my doctor to discuss any concerns relating to my illness and care in the presence of my family” and “I want my family/friends rather than my doctor to inform me about my impending death”. Justifications included, “I prefer to know that before them”, “Such information should be confidential; my permission should be obtained before informing others”, and “I don’t want to see them suffer for my suffering”. Interestingly, this was the only opinion type that did not assign priority score to “I want to die without having my body exposed”, indicating less concern about physical privacy. In the same vein, it gave the most extreme dis-priority score to “I want to die well dressed” and a dis-priority score to “I want to die clean”. It was also the only opinion type that did not have “I want to die being able to say the statement of faith” within the top two priorities.

Three priorities (having financial affairs in order, being able to communicate, and to be informed before family about impending death) and two dis-priorities (to die clean and to receive care from health care professionals trusty religious-wise) for this opinion type were not among the ten priorities and ten dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample.

Opinion type IV (decisional privacy concerned)

The eigenvalue and explained variance of opinion type IV were 4.4% and 6%, respectively. Six respondents belonged to this opinion type only, and three belonged both to this and other opinion types.

Opinion type IV displayed a strong decisional privacy concern. It assigned the third extreme priority score to “I want to make my own medical decisions” and priority scores to “I want the doctor to inform me about my impending death before informing my family”, “I want to receive medical information regularly from medical staff”, and “I want my medical status to be kept confidential from my family/friends”. Further, it assigned a dis-priority score to “I want my doctor to discuss any concerns relating to my illness and care in the presence of my family”. Justifications included, “I am used to making my own decision myself”, “I am the best to know my needs and wants”, “There may be opportunities for treatment that I want to be consulted about”, and “I want to make my decisions myself, it is nobody else’s business”. This opinion type was not concerned about some other aspects of life quality; it gave dis-priority scores to “I want to die maintaining my sense of humor”, “I want to die free of depression”, and “I want to die free of anxiety”. It was also not particularly concerned about life quantity as it gave dis-priority score to “I want to live longer regardless of my medical condition”.

Four priorities (making own medical decisions, being informed before family about impending death, receiving medical information regularly, and keeping medical status confidential from family/friends) and three dis-priorities (to die maintaining sense of humor, to die free of depression, and to die free of anxiety) for this opinion type were not among the ten priorities and ten dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample.

Opinion type V (life quantity concerned, family dependent)

The eigenvalue and explained variance of type V were 8.7% and 13%, respectively. Sixteen respondents belonged to this opinion type only, and 12 belonged both to this and other opinion types.

In contrast to the other four opinion types, opinion type V was life quantity concerned. It gave the most extreme dis-priority score to “I want to die at the peak of my life” and a dis-priority score to “If I go into coma, I don’t want to be placed in an intensive care unit”. Justifications included, “I don’t want to die if there is an opportunity to live”, “I want to live the full life”, and “I want to enjoy my life and see my kids married and do more of the good deeds”. Furthermore, dying in the hospital was only a weak dis-priority. Consistent with being life quantity concerned, it had a monitoring coping style as it strongly disagreed with “If I have a fatal illness, I don’t want to know”. Justifications included, “To seek treatment or accept death” and “I should know to evaluate my status”.

Opinion type V was described as family dependent as it strongly embraced “I want to have my family/friends with me at my last moments” and “I don’t want to die alone” and disagreed with “I want my medical status to be kept confidential from my family/friends”. Justifications included, “So that I don’t feel lonely”, “I want them to be around me to say good bye”, “I need them to pray for me”, and “They may help me”. Finally, it can be classified as rituals-apt; it was the only opinion type that assigned priority score to “I want my religious death rituals to be respected”, which may be an explanation for being family dependent.

This opinion type contributed the largest number of respondents to the entire sample. Nevertheless, two of its priorities (to be referred to as a person rather than a disease or number and not to die alone) and one of its dis-priorities (to have medical status confidential from family/friends) were not among the ten priorities and ten dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample.

Comparing normalized factor scores

Contrasting normalized scores of the 47 statements among the five opinion types supported our factor interpretation. Examples include: 1) normalized scores of statements, “I want to have no tubes inserted in my body” and “I don’t want to be kept on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery”, were 5.9/5.4, 4.2/4.7, 4.8/5.4, 5.0/5.3, and 4.3/4.3; for opinion types I (physical privacy concerned), II (whole person), III (pain and informational privacy concerned), IV (decisional privacy concerned), and V (life quantity concerned), respectively; 2) normalized score of statement, “I want to avoid being a financial burden to my family/friends” was 5.1 for opinion type I (family caring) and 4.7 for opinion type V (family dependent); 3) normalized scores of opinion types I (physical privacy concerned), III (informational privacy concerned), and IV (decisional privacy concerned) were, respectively, 6.0, 4.8, and 5.8 for statement, “I want to die without having my body exposed”, 5.0, 5.5, and 5.6 for statement, “I want the doctor to inform me about impending death before informing my family/friends”, and 3.9, 4.6, and 4.6 for statement, “If I have a fatal illness, I don’t want to know”.

Although all the five opinion types were highly transcendent, there were quantitative differences. Opinion types I, II, and V were more transcendent than opinion types III and IV; normalized scores were 6.8–7.3 vs 5.9–6.1 for “I want to die at peace with God” and 6.9–7.1 vs 5.9–6.3 for “I want to die being able to say the statement of faith.”

Association between identified opinion types and respondents’ characteristics

Table 4 summarizes respondents’ characteristics per opinion type. Compared to the other opinion types, opinion type I (physical and emotional privacy concerned, family caring) tended to have a younger age and lower self-rated religiosity (although it was the most transcendent by Q-methodology analysis). Opinion type II (whole person) tended to have higher self-rated religiosity. Opinion type III (pain and informational privacy concerned) tended to have lower life quality and to think less often about dying (and it was the least transcendent by Q-methodology). Opinion type IV (decisional privacy concerned) tended to have older age, lower general health, and higher life satisfaction. Opinion type V (life quantity concerned, family dependent) tended to have high life quality and low life satisfaction.

Indifferent (nonpriority) statements

Seven (15%) of the 47 statements received nonpriority scores on both averaging analysis and factor analysis. Four statements were related to family/friends, “I want to die at home”, “I want to avoid being an emotional burden to my family/friends”, “I want to discuss my fears about dying with my family/friends”, and “I want to avoid being a financial burden to my family/friends”. Two statements were related to life quality/quantity, “I want to die having no difficulty breathing” and “I don’t want to be kept on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery”, and one to health care professionals, “I want to have my doctor available to answer my questions”.

Sex differences

We took advantage of the fact that the previously reported study in males15 and the current study in females were performed in the same setting and used the same instrument. We compared the priorities and dis-priorities of the two sexes. Eight of the ten overall priorities and six of the ten overall dis-priorities were shared. However, to have financial affairs in order and to die clean were priorities for males only, whereas to be able to self-bath and feed and to be able to control bowels were priorities for females only. Further, to keep medical status confidential from family/friends, to have no tubes inserted into the body, to discuss dying fears with physician, and to discuss dying fears with family/friends were dis-priorities for males only, whereas to die well dressed, doctor to discuss illness and care with family present, to avoid being financial burden to society, and to receive medical care with compassion were dis-priorities for females only.

Quantitatively, females assigned significantly higher scores to the following statements: “I do not want to die alone”, “I want my medical status to be kept confidential from my family/friends”, “I want to make my own medical decisions”, “I want to have no tubes inserted into my body”, and “I want to die without having my body exposed”, with mean (95% confidence interval) difference of 1.25 (0.61–1.89, P<0.001), 0.86 (0.27–1.44, P=0.004), 0.81 (0.24–1.38, P=0.006), 0.72 (0.12–1.33, P=0.02), and 0.57 (0.06–1.07, P=0.03), respectively. Moreover, females assigned significantly lower scores to the following statements, “I want to die well dressed”, “I want to have my financial affairs in order before I die”, “I want to have an Islamic clergy with me at my last moments”, “I want to die clean”, and “I want to avoid being a financial burden to my society”, with mean (95% confidence interval) difference of 1.11 (0.50–1.72, P<0.001), 0.94 (0.31–1.57, P=0.003), 0.85 (0.20–1.51, P=0.01), 0.71 (0.17–1.24, P=0.009), and 0.64 (0.16–1.11, P=0.008), respectively.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to explore Saudi females’ choices regarding end-of-life priorities, using averaging analysis and Q-methodology, and compare them to previously reported choices of Saudi males. We found: 1) in females, the extreme ten priorities were to be able to say the statement of faith (shahadh), be at peace with God, not have the body exposed, maintain dignity, resolve all conflicts, have religious death rituals respected, have family/friends at last moments, be able to self-bath and feed, die free of pain, and be able to control bowels; 2) the extreme ten dis-priorities were to die in the hospital, die well dressed, be informed about impending death by family/friends rather than the doctor, die at peak of life, not know if one has a fatal illness, have doctor discuss illness and care in the family presence, live longer regardless of medical condition, avoid financial burden to society, not receive intensive care if in coma, and receive medical care with compassion; 3) Q-methodology analysis classified 62% of the 68 respondents into five opinion types: “physical and emotional privacy concerned, family caring”, “whole person”, “pain and informational privacy concerned”, “decisional privacy concerned”, and “life quantity concerned, family dependent”. Nevertheless, all the five opinion types were highly transcendent; 4) out of the extreme 14 priorities/dis-priorities for each of the five opinion types, 5 (36%), 6 (43%), 5 (36%), 7 (50%), and 3 (21%), respectively, were not among the extreme 20 priorities/dis-priorities identified by averaging analysis for the entire sample; 5) seven issues were identified as nonpriority both on averaging analysis and Q-methodology analysis, to die at home, to avoid being an emotional burden to family/friends, to discuss fears about dying with family/friends, to avoid being a financial burden to family/friends, to die having no breathing difficulty, not to be kept on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery, and to have the doctor available to answer questions; 6) compared to males, females assigned higher values to connectedness, physical privacy and self-dependence, informational and decisional privacy, and lower values to financial issues, spruceness, and rituals.

Transcendence

Consistent with our results in Saudi males15 and in contrast to results of North American25 and European26 studies, our respondents were highly transcendent; six of the ten end-of-life priorities were clearly (to be at peace with God, to be able to say the statement of faith, to resolve all conflicts, and to have religious death rituals respected) or arguably (to maintain dignity, not to have the body exposed) in the transcendence domain. However, to have religious death rituals respected was a priority for only one opinion type and to have an Islamic clergy at the last moments was actually a dis-priority for another, indicating that for some, intrapersonal aspects of religiosity are more important than its interpersonal expression. Interestingly, opinion type I, the group with the lowest self-declared religiosity, placed higher priority than the other groups on being at peace with God and being able to say the statement of faith, suggesting that spiritual needs at the end of life may not be easily predicted from apparent religious practices. Further, opinion type III appeared to be transcendent in a relatively less religious way, putting more value on being free of pain, maintaining dignity, and having financial affairs in order.

Life quality vs life quantity

Life quality and life quantity are often irreconcilable at the end of life, forcing people to choose. More than 60% of the African11,12 and European10 general public preferred life quality over life quantity. In this study, two of the overall ten dis-priorities indicated preference for life quantity (not to receive intensive care if in coma, to die at peak of life), whereas one of the ten dis-priorities (to live longer regardless of medical condition) and five of the ten priorities (to die without having body exposed, to die maintaining dignity, to die being able to self-bath and feed, to die free of pain, and to die being able to control bowels) indicated preference for life quality. Further, only one of the five opinion types was found to be life quantity concerned, whereas the others were either whole person concerned or life quality concerned.

Life quality is conceptualized differently among people. Pain was the most concerning of nine common end-of-life symptoms and problems to the Namibian general public.12 However, to die free of pain was the ninth priority in this study and the tenth priority in Saudi males.15 Moreover, to die free of pain was one of the seven top priorities for only one of the five opinion types. Further, while some psychological (freedom from depression, freedom from anxiety, maintaining sense of humor, being referred to as a person not a disease or number, receiving medical care with compassion) and physiologic (freedom from difficulty breathing, being able to communicate) aspects of life quality were nonpriorities or weak dis-priorities for Saudi females, aspects related to physical privacy and self-dependence (without having the body exposed, maintaining dignity, being able to self-bath and feed, being able to control bowels) were important priorities.

Privacy

Privacy can be classified into physical, decisional, informational, and emotional. The importance of physical privacy was apparent from averaging analysis. However, Q-methodology analysis revealed preferences for other types of privacy that were otherwise masked.

Self-decision making was an overall nonpriority for our respondents. However, it was a priority for one of the five opinion types along with receiving medical information regularly. We have previously found that Mill’s individual autonomy, including self-decision making, was the preferred model for the purpose of clinical informed consent among Saudis.27 On the other hand, a shared decision-making model for end-of-life care was preferred by 74% of the European general public10 and ~50% of the Kenyan and Namibian general public.11,12

One of the ten overall dis-priorities indicated preference for terminal illness disclosure to the patient and two indicated preference for information confidentiality from family/friends. In addition, two opinion types assigned priority score to being informed about impending death before the family/friends, embracing informational privacy. This finding agrees with other studies showing that ~56% of the general public wanted to be told if they had limited time left without having to ask11,12 and suggests that “Western” reasonable patient standard of information disclosure may be appropriate in the Saudi culture,28 in contrast to what have been hypothesized.29 It is of note that governing codes on disclosure of terminal illness to patients and families vary considerably in Islamic countries.30

Finally, for one opinion type, the importance of emotional privacy was highlighted by assigning the extreme dis-priority to discussing dying fears with the physician.

We found that respondents who valued emotional privacy mostly tended to be younger and respondents who valued decisional privacy mostly tended to be older, suggesting a possible association between end-of-life preferences and respondents’ demographics; however, this needs to be prospectively studied.

Connectedness and preferred place of death

One of the ten overall priorities (to have family/friends at last moments) and the most extreme dis-priority (to die in hospital) indicated the importance of connectedness. Different reasons may underlie wanting to have family/friends present at the time of death. Q-methodology analysis was able to identify a family caring group who wanted to prepare family/friends to accept death and a family-dependent group who do not want to die alone.

To die in the hospital was the most extreme overall dis-priority; however, it was the seventh dis-priority for opinion type V that was classified as life quantity concerned. Home as a place of death was preferred by 51%–84%, 51%, and 32% of the European, Kenyan, and Namibian general public, respectively.7,11,12

Usefulness of Q-methodology

Forced ranking and factor analysis in Q-methodology avoid the independent-rating tendency to attribute maximum importance to a large number of priorities14 and the homogenization and depersonalizing effect of averaging analysis, respectively.15 Indeed, in this study, Q-methodology revealed latent constellations of end-of-life choices and unmasked 21%–50% of the 14 priorities/dis-priorities for the five opinion types.

Sex differences

Twenty percent of the top ten priorities and 40% of the top ten dis-priorities identified in this study were not among the ten top priorities and ten top dis-priorities reported previously for Saudi males.15 In addition, ranking scores were significantly different for ten (21%) of the 47 statements between males and females. It appears that compared to Saudi males, Saudi females assign higher values to connectedness (not to die alone, to discuss dying fears with physician, to discuss dying fears with family/friends), to informational privacy (confidentiality of medical status from family/friends, not to discuss concerns about illness and care in the family presence), to decisional privacy (to make own medical decisions), and to physical privacy and self-dependence (body modesty, to be able to self-bath and feed, to be able to control bowels, not to have tubes inserted into the body) and lower values to financial issues (to have financial affairs in order, to avoid being a financial burden to society), to spruceness (to die well dressed, to die clean), and to rituals (to have an Islamic clergy at last moments). The results indicate that there may be important sex-related differences in end-of-life priorities in addition to the known culture-related differences.

Study limitations

The following limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study. The study was based on a volunteer sample recruited at a single tertiary health care institution, and because of the mental demands of forced ranking, only individuals with high school education or more were eligible. Thus, the results may not be generalizable even though the institution is a governmental referral center for the entire country. Further, the study recruited healthy individuals rather than individuals at end of life. Nevertheless, studying such individuals have enriched our understanding of end-of-life choices6–12 since they are likely to reflect internalized norms and general beliefs of their society. Moreover, Q-methodology is by definition exploratory and nonexhaustive in nature and does not assume discontinuous data or clear cut-off points between categories. So, it is likely that there are opinion types other than the five identified in this study; the study is not likely to reflect the prevalence of the identified opinion types among the larger population, and the five opinion types should be considered impressionistic conclusion.

Conclusion

Our results support the following conclusion: 1) in adult Saudi females, transcendence was the extreme end-of-life priority and dying in the hospital was the extreme dis-priority; 2) body modesty and family presence at the last moments were among the overall priorities; 3) emotional, informational, and decisional privacy, pain, and life quantity were variably emphasized by different opinion-based groups identified by Q-methodology analysis; 4) several priorities and dis-priorities were masked by averaging analysis but disclosed by Q-methodology analysis; 5) there were important quantitative and qualitative sex differences in end-of-life choices; females assigned higher values to connectedness, physical privacy and self-dependence, informational privacy, and decisional privacy and lower values to financial issues, spruceness, and rituals. The results expand on worldwide literature on end-of-life preferences and on our previous study on Saudi males and emphasize the need to consider broader meanings of life quality, interculture and intraculture diversity in combining and prioritizing end-of-life issues, sex, and faith and religion to achieve the goal of quality death and dying.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by a grant from KFSH&RC to MMH. KFSH&RC had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. SH is the daughter of MMH.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, Institute of Medicine; 1997. | ||

The SUPPORT Principle Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatment (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591–1598. | ||

Singer PA, Bowman KW. Quality end-of-life care: a global perspective. BMC Palliat Care. 2002;1(1):4. | ||

Rao JK, Alongi J, Anderson LA, Jenkins L, Stokes GA, Kane M. Development of public health priorities for end-of-life initiatives. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5):453–460. | ||

Halpern SD. Toward evidence-based end-of-life care. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2001–2003. | ||

Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G. What are cancer patients’ preferences about treatment at the end of life, and who should start talking about it? A comparison with healthy people and medical staff. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(4):206–214. | ||

Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, et al; PRISMA. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2006–2015. | ||

Harding R, Simms V, Calanzani N, et al; PRISMA. If you had less than a year to live, would you want to know? A seven-country European population survey of public preferences for disclosure of poor prognosis. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2298–2305. | ||

Daveson BA, Bausewein C, Murtagh FE, et al; PRISMA. To be involved or not to be involved: a survey of public preferences for self-involvement in decision-making involving mental capacity (competency) within Europe. Palliat Med. 2013;27(5):418–427. | ||

Higginson IJ, Gomes B, Calanzani N, et al; Project PRISMA. Priorities for treatment, care and information if faced with serious illness: a comparative population-based survey in seven European countries. Palliat Med. 2014;28(2):101–110. | ||

Downing J, Gomes B, Gikaara N, et al; Project PRISMA. Public preferences and priorities for end-of-life care in Kenya: a population-based street survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):4. | ||

Powell RA, Namisango E, Gikaara N, et al. Public priorities and preferences for end-of-life care in Namibia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(3):620–630. | ||

Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH. Concordance of preferences for end-of-life care between terminally ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(6):510–518. | ||

Downey L, Engelberg RA, Curtis R, Lafferty WE, Patrick DL. Shared priorities for the end-of-life period. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(2):175–188. | ||

Hammami MM, Al Gaai E, Hammami S, Attala S. Exploring end of life priorities in Saudi males: usefulness of Q-methodology. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14(1):66. | ||

Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Herting JR, Engelberg RA. The quality of dying and death (QODD) questionnaire: empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(1):9–22. | ||

McKeown B, Thomas D. Q Methodology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988. | ||

Thomas DM, Watson RT. Q-sorting and MIS research: a primer. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. 2002;8:141–156. | ||

Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825–832. | ||

Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(3):727–737. | ||

Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Correspondence between patients’ preferences and surrogates’ understandings for dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(6):498–509. | ||

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):17–31. | ||

Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(3):717–726. | ||

Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. | ||

Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–2482. | ||

Miccinesi G, Bianchi E, Brunelli C, Borreani C. End-of-life preferences in advanced cancer patients willing to discuss issues surrounding their terminal condition. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2012;21(5):623–633. | ||

Hammami MM, Al-Gaai EA, Al-Jawarneh Y, et al. Patients’ perceived purpose of clinical informed consent: Mill’s individual autonomy model is preferred. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:2. | ||

Hammami MM, Al-Jawarneh Y, Hammami MB, Al Qadire M. Information disclosure in clinical informed consent: “reasonable” patient’s perception of norm in high-context communication culture. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:3. | ||

Del Pozo PR, Fins JJ. Islam and informed consent: notes from Doha. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2008;17(3):273–279. | ||

Abdulhameed HE, Hammami MM, Mohamed EA. Disclosure of terminal illness to patients and families: diversity of governing codes in 14 Islamic countries. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(8):472–475. |

Supplementary material

Q-set statements and domains

The final Q-set consisted of 47 statements with eight thematic domains: symptoms and personal control (7), treatment preferences (5), whole-person concerns (8), moment of death (5), family/friends (6), achieving sense of completion/spirituality/religiosity (5), preparation for death (5), and relationship with health care professionals (6). The first three domains are most related to life quality vs quantity concerns, the fourth and fifth to connectedness, the sixth to transcendence, the seventh to coping, and the eighth to information disclosure and decision making. Each statement was randomly assigned a number from 1 to 47.

Life quality vs life quantity

Symptoms and personal control

2. I want to die having no difficulty breathing

7. I want to die free of anxiety

8. I want to die free of pain

9. I want to die free of depression

30. I want to die being able to control my bladder

33. I want to die being able to bathe and feed myself

34. I want to die being able to control my bowels

Treatment preferences

1. I want to have no tubes inserted into my body

6. If I go into coma, I do not want to be placed in an intensive care unit

10. I want to receive all available treatments no matter what the chances of success are

11. I do not want to be kept on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery

12. I want to live longer regardless of my medical condition

Whole-person concerns

27. I want to die being able to communicate with others

31. I want to die at the peak of my life

35. I want to die maintaining my dignity

37. I want to die clean

41. I want to be referred to as a person not as a disease or a number

42. I want to die without having my body exposed

43. I want to die maintaining my sense of humor

44. I want to die well dressed

Connectedness

Moment of death

3. I want to die in the hospital

23. I do not want to die alone

26. I want to die at home

28. I want to have my family/friends with me at my last moments

40. I want to have an Islamic clergy with me at my last moments

Family/friends

13. I want my family/friends rather than my doctor to inform me about my impending death

21. I want my doctor to discuss any concerns relating to my illness and care in the presence of my family

22. I want my medical status to be kept confidential from my family/friends

25. I want to avoid being an emotional burden to my family/friends

29. I want to die knowing that my family/friends are prepared to accept my death

47. I want to avoid being a financial burden to my family/friends

Transcendence

Achieving sense of completion/spirituality/religiosity

24. I want to resolve any conflict before I die

36. I want to die at peace with God

38. I want to die being able to say the statement of faith (shahadah)

39. I want my religious death rituals to be respected

45. I want to avoid being a financial burden to my society

Coping

Preparation for death

14. I want to discuss my fears about dying with my physician

15. I want to discuss my fears about dying with my family/friends

18. If I have a fatal illness, I don’t want to know

32. I want to die instantaneously

46. I want to have my financial affairs in order before I die

Information disclosure and decision making

Relationships with health care professionals

5. I want to receive medical care with compassion

4. I want to receive care from health care professionals whom I religiously trust

16. I want the doctor to inform me about my impending death before informing my family

17. I want to make my own medical decisions

19. I want to have my doctor available to answer my questions

20. I want to receive medical information regularly from medical staff

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.