Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 11

Tramadol: a valuable treatment for pain in Southeast Asian countries

Authors Vijayan R , Afshan G, Bashir K , Cardosa M , Chadha M, Chaudakshetrin P , Hla KM, Joshi M, Javier FO, Kayani AG , Musba AT, Nimmaanrat S , Pantjawibowo D, Que JC, Vijayanand P

Received 11 January 2018

Accepted for publication 17 April 2018

Published 24 October 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 2567—2575

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S162296

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

Ramani Vijayan,1 Gauhar Afshan,2 Khalid Bashir,3 Mary Cardosa,4 Madhur Chadha,5 Pongparadee Chaudakshetrin,6 Khin Myo Hla,7 Muralidhar Joshi,8 Francis O Javier,9 Asif Gul Kayani,10 Andi Takdir Musba,11 Sasikaan Nimmaanrat,12 Dwi Pantjawibowo,13 Jocelyn C Que,14 Palanisamy Vijayanand15

1Department of Anaesthesiology, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2Department of Anaesthesiology, The Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan; 3Department of Anaesthesia, Hameed Latif Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan; 4Department of Anaesthesiology, Hospital Selayang, Selangor, Malaysia; 5Department of Pain Medicine, Primus Hospital and Fortis Group of Hospitals, New Delhi, India; 6Pain Management Clinic, Department of Anesthesiology, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 7Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Yangon General Hospital, University of Medicine-1, Yangon, Myanmar; 8Department of Anaesthesia & Pain Medicine, Virinchi Hospitals, Hyderabad, India; 9Pain Management Center, St Luke’s Medical Center, Metro Manila, Philippines; 10Department of Anesthesiology, Kulsum International Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan; 11Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia; 12Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hatyai, Songkhla, Thailand; 13Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Therapy, and Hospital Pain Management, Premier Bintaro Hospital, South Tangerang, Indonesia; 14Center for Pain Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines; 15Pain Management Department, Sri Ramakrishna Hospital, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Background: The supply of controlled drugs is limited in the Far East, despite the prevalence of health disorders that warrant their prescription. Reasons for this include strict regulatory frameworks, limited financial resources, lack of appropriate training amongst the medical profession and fear of addiction in both general practitioners and the wider population. Consequently, the weak opioid tramadol has become the analgesic most frequently used in the region to treat moderate to severe pain.

Methods: To obtain a clearer picture of the current role and clinical use of tramadol in Southeast Asia, pain specialists from 7 countries in the region were invited to participate in a survey, using a questionnaire to gather information about their individual use and experience of this analgesic.

Results: Fifteen completed questionnaires were returned and the responses analyzed. Tramadol is used to manage acute and chronic pain caused by a wide range of conditions. Almost all the specialists treat moderate cancer pain with tramadol, and every one considers it to be significant or highly significant in the treatment of moderate to severe non-cancer pain. The reasons for choosing tramadol include efficacy, safety and tolerability, ready availability, reasonable cost, multiple formulations and patient compliance. Its safety profile makes tramadol particularly appropriate for use in elderly patients, outpatients, and for long-term treatment. The respondents strongly agreed that tighter regulation of tramadol would reduce its medical availability and adversely affect the quality of pain management. In some countries, there would no longer be any appropriate medication for cancer pain or the long-term treatment of chronic pain.

Conclusions: In Southeast Asia, tramadol plays an important part in the pharmacological management of moderate to severe pain, and may be the only available treatment option. If it were to become a controlled substance, the standard of pain management in the region would decline.

Keywords: tramadol, questionnaire, indications, efficacy, safety, controlled substance

Introduction

The unmet need for effective pain management remains high, particularly in low and middle income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that tens of millions of people experience moderate to severe pain every year without access to treatment, including 5.5 million with terminal cancer and a million with late stage HIV infection.1 Research has shown that the availability of controlled opioid analgesics – such as morphine, hydrocodone and fentanyl – is very limited in many parts of the world, including the Asian region.2–4

WHO Expert Committees advise the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs about pharmaceutical agents which should be designated controlled substances – ie, have their manufacture, possession, or use regulated by a government – on the basis of their individual therapeutic profiles and risk of abuse. Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic combining both opioid and non-opioid mechanisms of action that has been used to treat moderate to (moderately) severe cancer and non-cancer pain for several decades.5 It has been assessed several times by the WHO, but in each case it was decided not to bring it under international control.6

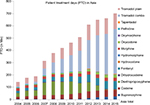

Intercontinental Marketing Services Kilochem statistics show that – except for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and paracetamol – tramadol and tramadol-containing products are the analgesics most often used in clinical practice in a large group of Asian countries, with increasing consumption over time (Figure 1).

To obtain a clearer picture of the role and clinical use of tramadol in the Far East, pain specialists from 7 countries in the region were invited to participate in a pilot survey, which was drawn up in compliance with the Healthcare Professional Code of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations.7 A questionnaire was developed to gather information about their use of tramadol, their experience of its abuse potential in clinical practice, and the influence of regulatory controls on medical availability.

Tramadol

Tramadol [2-(dimethylaminomethyl)–1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol] is a racemic 1:1 mixture of two enantiomers, (+)-tramadol and (−)-tramadol, which differ in their potencies at opioid receptors and monoamine uptake sites.8 Their mechanisms of action are complementary and synergistic: the (+)-enantiomer is a selective agonist at the µ-opioid receptor and inhibits serotonin reuptake, while the (–)-enantiomer mainly inhibits noradrenaline uptake.9,10 Furthermore, the (+)-enantiomer is rapidly metabolized to mono-O-desmethyltramadol (M1 metabolite), which binds to the µ-opioid receptor with an affinity two orders of magnitude higher than that of the parent compound and ~1/10 that of morphine.9,11

Tramadol is extensively metabolized in the liver by O- and N-demethylation and by conjugation reactions to form glucuronides and sulfates. The elimination of both tramadol and its metabolites is predominantly via the kidneys, with about 30% of the dose excreted in the urine as the parent drug and the rest excreted as metabolites.12

The contraindications for treatment with tramadol include acute respiratory depression, head injury, raised intracranial pressure, acute intoxication and uncontrolled epilepsy.13

Methods

The questionnaire shown in Table 1 was emailed to 17 pain specialists who expressed an interest in participating, in India (3), Indonesia (3), Malaysia (2), Myanmar (2), Pakistan (3), the Philippines (2) and Thailand (2). The questions were formulated to identify their individual reasons for prescribing tramadol and the conditions for which they prescribed it, as well as the significance of tramadol in the management of pain and the likely impact of tighter regulation on treatment – both in hospital and in the community – in their own countries. A total of 15 completed questionnaires were returned and the responses analyzed in November 2016.

| Table 1 Questionnaire on the role of tramadol in pain management Abbreviation: NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

Results

Indications for which tramadol is prescribed

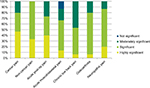

According to the experts, tramadol is used in the management of moderate to severe acute and chronic pain caused by a wide range of conditions. Their rating of the significance of tramadol as a treatment option for various pain indications is shown in Figure 2.

| Figure 2 Significance of tramadol in various acute and chronic pain indications. |

Almost all the specialists treat moderate cancer pain with tramadol, a modality that is supported in the literature.13–15 Most of them rated it as significant or highly significant in managing this condition. Important factors influencing their choice of analgesic was tramadol’s efficacy in both nociceptive and neuropathic pain,16 which often occur concurrently in cancer pain,17 its position as a step two analgesic on the WHO “pain ladder”, and patients’ preference for it over low-dose strong opioids. Respondents from India, Indonesia and Pakistan also stated that there is limited or no availability of controlled opioid analgesics in their countries. Although tramadol does not have the same potency as strong opioid analgesics such as morphine for treating severe cancer pain, tramadol is often the only option available.

Every one of the respondents considered tramadol to be either significant or highly significant in the treatment of moderate to severe non-cancer pain in their home country, specifically mentioning acute indications such as labor pain, postoperative and post-traumatic pain, and chronic indications such as low back pain and osteoarthritis. It is considered an alternative to NSAIDs or strong opioids, particularly suitable for elderly patients or those with poor liver and/or renal function.18

The majority of respondents rated tramadol as significant or highly significant in the management of acute postoperative pain and acute musculoskeletal pain. Specific examples quoted were the combination of tramadol with WHO step one analgesics or as an alternative to them, and its use as a step-down analgesic from strong opioids following surgery.

Efficacy must be carefully balanced against safety when long-term treatment is required for chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain, and around three-quarters of respondents regarded tramadol as being significant or highly significant in managing these conditions. Factors contributing to this rating included its efficacy in mixed pain (ie, with nociceptive and neuropathic components), and its favorable benefit/risk ratio in prolonged use. It was specifically noted that the safety issues associated with NSAIDs often limit their use, particularly in chronic pain patients and the elderly, so tramadol is frequently substituted – an approach which is reflected in the current literature.19,20

Over three-quarters of the specialists also rated the use of tramadol in neuropathic pain as significant or highly significant in their own country, mostly as a second line option after drugs such as gabapentin. This is in line with international recommendations.21

One respondent from India also prescribes tramadol for fibromyalgia; both tramadol monotherapy and tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets have been shown to reduce pain levels associated with this poorly understood condition.22,23

In the case of specific patient groups, around three-quarters of respondents considered the current use of tramadol to be significant or highly significant for adult and elderly patients. The proportion was lower for children, at less than one-third, primarily because the specialists have much less clinical experience with pediatric patients. The reasons given for the high significance accorded to tramadol in pain management are listed in Table 2, and broadly mirror the factors influencing the choice of analgesic outlined below.

| Table 2 Reasons for the high significance of tramadol in pain management Abbreviation: NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

Reasons for prescribing tramadol

Efficacy

The main reason for choosing tramadol to manage pain in Asia – reflected by its high usage – is the wide-ranging effectiveness resulting from its unique multimodal mechanisms of action, which are well established.16,24–27 The responses confirm that tramadol effectively treats both acute and chronic pain, as well as nociceptive and neuropathic pain. This makes it particularly valuable for managing pain states such as cancer pain and chronic low back pain, which often have both nociceptive and neuropathic components.28 In the case of chronic pain, its risk-benefit profile in long-term use offers advantages over other drugs, such as NSAIDs. Some respondents referred specifically to the advantages of tramadol’s classification as a WHO step two compound, positioned after simple analgesics (NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, paracetamol) and before the need for strong opioids. In countries with limited or no access to strong opioids, tramadol may be the only reliably available stronger analgesic for pain patients.

Safety and tolerability

Another decisive factor in the choice of tramadol is its safety profile. It is frequently chosen in preference to NSAIDs, which may cause renal and gastrointestinal impairment in long-term use. Selective COX-2 inhibitors and especially NSAIDs are associated with an elevated risk of severe gastrointestinal, renal and cardiovascular side effects,29–32 and the risk increases with the duration of treatment. It is therefore recommended that the lowest dose of these agents to control symptoms should be prescribed for the shortest time.33 Tramadol is not associated with these side effects, and several responders specifically cited its suitability for long-term use in patients with chronic pain as a strong influence on their choice of analgesic.

The side effect profile of strong opioids may include nausea and vomiting, hypotension, tachycardia, respiratory depression, abuse and neurological symptoms.34 While the incidence of nausea and vomiting is not significantly different between tramadol and strong opioids, especially in opioid-naïve patients and depending upon the route of administration, the general experience of the specialists is that tramadol is well tolerated. Patients have fewer typical µ-opioid side effects, particularly a reduced risk of respiratory depression,25 which has been confirmed by randomized clinical trials.35–37 This is in line with the observation from Vazzana et al that the advantages of tramadol over other opioid medications are its unique pharmacological profile, the lower incidence of typical µ-opioid side effects and its lower abuse potential.38 Like many other opioids, tramadol can induce seizures.39 However, these occur mainly after administering tramadol in doses which exceed the recommended upper limit or in combination with medicinal products that lower the seizure threshold. In patients with epilepsy or who are susceptible to seizures it should be avoided. The concomitant use of tramadol and serotonergic drugs may cause serotonin toxicity.

The respondents generally considered the abuse potential of tramadol to be either lower or much lower than that of strong opioids, and that it presents a lower risk of addiction. This is supported by experimental and clinical findings40–42 and reflects the current view of the WHO, which concluded in its 2014 assessment that international control status is not warranted. Nevertheless, substances with a low abuse potential may lead to a level of abuse under certain circumstances, which may require targeted national measures to address the specific problem. This has been the case in Thailand, where the abuse of tramadol – mainly by adolescents – has led to targeted measures by the local authorities.

Overall, the experts concluded that the safety profile of tramadol makes it particularly appropriate for use in elderly patients, in the outpatient setting, and for longer periods of time.

Easy availability at reasonable cost

Tramadol is easily obtained on prescription in most Southeast Asian countries and – as it is a generic analgesic – is relatively inexpensive. Conversely, strong opioids are generally subject to restrictive legal controls and may not even be available to hospitals. The cost of morphine is generally low, but that of newer opioids such as oxycodone, fentanyl and buprenorphine – or specific formulations – is usually higher than that of tramadol. Also, supplies of strong opioids tend to be intermittent and, unlike tramadol, only a limited range of formulations is available. According to one respondent from India, tramadol is the only non-NSAID analgesic obtainable in that country in a formulation designed for oral administration.

Multiple formulations

The range of formulations available in the Far East includes 1) drops, capsules and tablets for oral use; and 2) solutions for intramuscular, intravenous and subcutaneous injection. Oral formulations are produced in both immediate release and sustained release versions. Among the benefits of sustained release are that it decreases peak plasma concentrations and thereby reduces adverse effects, while the concomitant simpler dosing regimen may improve patient compliance. In much of the Far East a range of formulations is available, allowing the clinician considerable scope to individualize treatment.

Patient compliance

Most respondents find that tramadol is well tolerated and one specifically mentioned patient compliance as a factor in the choice of analgesic. In some countries such as the Philippines there is also a cultural influence; morphine has a stigma and many patients believe they will become addicted to it, so compliance is poor. By contrast, tramadol is more readily accepted.

The potential impact of more stringent controls on availability and treatment

Respondents strongly agreed that tighter regulation would lead to a significant reduction in the medical availability of tramadol, especially in the outpatient setting. In order to compensate for this reduced availability, other analgesics would be substituted; mainly NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors and – in the hospital setting in a few countries – strong opioids. If NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors were to be prescribed, their lower efficacy means that fewer patients would achieve satisfactory pain relief, especially those with conditions which have a neuropathic pain component. There would also be a higher incidence of serious side effects on the gastrointestinal, renal and cardiovascular systems, especially over the long term or in elderly patients. Other possible consequences mentioned by respondents include the higher cost of alternative analgesics and a decline in patient compliance, owing to patients’ fears of addiction to strong opioids and their possible side effects.

All the respondents stated that the quality of pain management would be adversely affected, so many patients would be left without appropriate treatment for moderate to severe pain, especially in the outpatient setting. As strong opioids are not readily available in several countries, including India and Pakistan, some respondents foresee they would no longer have any appropriate medication for cancer pain or the long-term treatment of chronic pain. The experts’ opinion is supported by a survey, conducted by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) in 2013,43 which confirmed the negative impact of an international scheduling on the availability of tramadol. In total, 72% of responders (33 of 46 countries) expressed concern that the introduction of control measures would limit accessibility to tramadol and make doctors more reluctant to prescribe it, which reflects past experience of national tramadol controls leading to reduced medical availability.43,44

Discussion

Tramadol has become the analgesic mostly frequently used in the Far East to treat moderate to severe pain. It is readily available and relatively cheap. This survey indicates that the utilization of tramadol is based upon several factors:

- proven efficacy in treating various cancer and non-cancer indications, supported by its inclusion in national/medical society guidelines in 5 of the 7 countries surveyed;

- safety and tolerability compared to NSAIDs and strong opioids;

- ease of storage and prescription compared to controlled strong opioids;

- after major surgery, it can be used as a step-down analgesic following patient-controlled or epidural analgesia; and

- it can be combined with NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors or paracetamol to augment analgesia.

The experts’ responses clearly indicate that tramadol is a valuable option to treat moderate to severe pain of diverse origin. It is prescribed when non-opioids such as paracetamol, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors provide insufficient analgesia, are not tolerated, or are contra-indicated, and where strong opioids are not justified or are unavailable. This use is reflected by tramadol being included in a number of national and international guidelines,45–47 and is in line with its role in therapy as described in the international literature.25,48,49

Chronic pain is an important public health issue. The Declaration of Montreal states that access to pain management is a fundamental human right, and that all people with pain should have access to appropriate assessment and treatment without discrimination.50 However, studies have concluded that 5.5 billion people (~83% of the world’s population) live in countries with low to non-existent access to controlled opioid analgesics, and only 460 million (7%) have adequate access.1,2 The reasons for poor accessibility include strict national regulations, lack of training in their use, and fear of addiction among both health care professionals and the general population. The United Nations’ 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs states the dual obligation to ensure that controlled substances are available for medical purposes and to protect populations against abuse and diversion.51 The importance of making these substances available for those who need them is continuously highlighted, eg, by international human rights organizations, the WHO, the INCB, the World Health Assembly and regional intergovernmental organizations.

In the Far East, the limited supply of controlled drugs is illustrated by the fact that in 2005 the whole of Asia accounted for only 3% of the world’s consumption of opioids, compared to 67% for Europe.52 The situation has changed little since: between 2001–2003 and 2011–2013 the worldwide consumption of opioids has more than doubled, yet in India it increased by only 10% and in Myanmar it actually declined.53 A number of barriers to wider use in the region have been identified; these include onerous regulatory frameworks, restricted financial resources, and an absence of appropriate training amongst the medical profession.53 In some countries a fear of addiction among both general practitioners and the wider population also acts as a disincentive.53,54 The disparity between the availability of opioid analgesics and the prevalence of health disorders that warrant their prescription remains a major cause of concern. Moreover, the prevalence of certain pain syndromes (eg, joint pain, neuralgias) is projected to increase further in the coming decades, owing to the rapidly increasing elderly population55; eg, Asia is projected to see a >60% increase in the number of older people (60 years and over) between 2015 and 2030.56

If tramadol were to become a controlled substance, the responses reveal a widely held belief that the medical availability of tramadol would be severely curtailed in the region, especially in the outpatient setting, and the unmet need for pain relief would increase significantly.

A key limitation of this survey is the small sample size, but the responses from the disparate countries were highly consistent over the range of questions.

Conclusions

In Southeast Asia, tramadol or tramadol-containing analgesics play an important part in the pharmacological management of moderate to severe pain. It provides a stronger – and for many patients a safer – alternative to high doses of NSAIDs or low doses of morphine, oxycodone or other strong opioids. In addition, there are many situations where tramadol is the only available option for treating moderate to severe pain, accessible to inpatients and outpatients in regions where controlled opioids are unobtainable. Pain specialists in the region consider that access to tramadol would clearly be reduced if it were to become a controlled substance. As a direct consequence, the quality of pain management would decline, particularly for patients who require longer term treatment, and for some patients appropriate medication would no longer be available.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Derrick Garwood of Derrick Garwood Ltd, Cambridge, UK. Support for this assistance was funded by Grünenthal GmbH, of Aachen, Germany.

The survey and this manuscript were funded by Grünenthal GmbH of Aachen, Germany.

Disclosure

Ramani Vijayan has received consultancy fees from Pfizer and Grünenthal GmbH during the past 2 years. Mary Cardosa has acted as a consultant and/or received honoraria for scientific lectures from Pfizer, Menarini, Mundipharma, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Francis O. Javier has given lectures for Mundipharma Philippines, participated in Advisory Boards for Mundipharma Philippines and Menarini Philippines, and received travel grants for conferences from both these companies. Jocelyn C. Que has received honoraria for speaking at professional meetings from Abbott Philippines, Menarini, Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), Mundipharma and Pfizer-Hospira. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

National Drug Control Strategies and Access to Controlled Medicines. Human Rights Watch; 2016. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/national_drug_control_strategies_and_access_to_controlled_medicines_2016.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2016. | ||

Seya MJ, Gelders SF, Achara OU, Milani B, Scholten WK. A first comparison between the consumption of and the need for opioid analgesics at country, regional, and global levels. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(1):6–18. | ||

Cleary J, Silbermann M, Scholten W, Radbruch L, Torode J, Cherny NI. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in the Middle East: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 11):xi51–xi59. | ||

Duthey B, Scholten W. Adequacy of opioid analgesic consumption at country, global, and regional levels in 2010, its relationship with development level, and changes compared with 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(2):283–297. | ||

Raffa RB, Friderichs E. The basic science aspect of tramadol hydrochloride. Pain Rev. 1996;3(4):249–271. | ||

Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. Tramadol Update Review Report. Thirty-sixth Meeting. 16–20 June. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2014. | ||

Code H.P. European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations; 2018. Available from: https://www.efpia.eu/relationships-codes/healthcare-professionals-hcps/. Accessed April 9, 2018. | ||

Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, et al. Complementary and synergistic antinociceptive interaction between the enantiomers of tramadol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267(1):331–340. | ||

Frink MC, Hennies HH, Englberger W, Haurand M, Wilffert B. Influence of tramadol on neurotransmitter systems of the rat brain. Arzneimittelforschung. 1996;46(11):1029–1036. | ||

Dayer P, Desmeules J, Collart L. Pharmacology of tramadol. Drugs. 1997;53(Suppl 2):18–24. | ||

Gillen C, Haurand M, Kobelt DJ, Wnendt S. Affinity, potency and efficacy of tramadol and its metabolites at the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362(2):116–121. | ||

Gong L, Stamer UM, Tzvetkov MV, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: tramadol pathway. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24(7):374–380. | ||

British National Formulary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/tramadol-hydrochloride.html#contraIndications. Accessed February 12, 2018. | ||

Leppert W, Łuczak J. The role of tramadol in cancer pain treatment--a review. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(1):5–17. | ||

Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, Berti M, Roila F, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7):vii139–vii154. | ||

Hollingshead J, Dühmke RM, Cornblath DR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD003726. | ||

Vadalouca A, Raptis E, Moka E, Zis P, Sykioti P, Siafaka I. Pharmacological treatment of neuropathic cancer pain: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Pain Pract. 2012;12(3):219–251. | ||

Schug SA. The role of tramadol in current treatment strategies for musculoskeletal pain. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(5):717–723. | ||

Pergolizzi JV, van de Laar M, Langford R, et al. Tramadol/paracetamol fixed-dose combination in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:327–346. | ||

Makris UE, Abrams RC, Gurland B, Reid MC. Management of persistent pain in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(8):825–836. | ||

Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–173. | ||

Russell IJ, Kamin M, Bennett RM, Schnitzer TJ, Green JA, Katz WA. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2000;6(5):250–257. | ||

Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, Rosenthal N. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2003;114(7):537–545. | ||

Lehmann KA. Tramadol for the management of acute pain. Drugs. 1994;47(Suppl 1):19–32. | ||

Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(13):879–923. | ||

Campbell W. Current options in the drug management of nociceptive pain; 2007. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/psb.66/pdf. Accessed November 11, 2016. | ||

Mattia C, Coluzzi F. Tramadol: a wonder drug for the treatment of chronic pain? Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;5(1):1–4. Available from:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a104/cbfc306dc78a519f7028443b291f063f12c1.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018. | ||

Morlion B. Pharmacotherapy of low back pain: targeting nociceptive and neuropathic pain components. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(1):11–33. | ||

Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding after the introduction of COX 2 inhibitors: ecological study. BMJ. 2004;328(7453):1415–1416. | ||

Whelton A. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med. 1999;106(5B):13S–24. | ||

Harbin M, Turgeon RD, Kolber MR. Cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(3):e166. | ||

Hsu CC, Wang H, Hsu YH, Chuang SY, et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of chronic kidney disease in subjects with hypertension: nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):524–533. | ||

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ktt13/resources/nonsteroidal-antiinflammatory-drugs-58757951055301. Accessed November 11, 2016. | ||

Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–120. | ||

Wilder-Smith CH, Hill L, Osler W, O’Keefe S. Effect of tramadol and morphine on pain and gastrointestinal motor function in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(6):1107–1116. | ||

Gritti G, Verri M, Launo C, et al. Multicenter trial comparing tramadol and morphine for pain after abdominal surgery. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1998;24(1):9–16. | ||

Grond S, Radbruch L, Meuser T, Loick G, Sabatowski R, Lehmann KA. High-dose tramadol in comparison to low-dose morphine for cancer pain relief. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(3):174–179. | ||

Vazzana M, Andreani T, Fangueiro J, et al. Tramadol hydrochloride: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse side effects, co-administration of drugs and new drug delivery systems. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;70:234–238. | ||

Serious reactions with tramadol: seizures and serotonin syndrome. New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority; 2007. Available from: http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/PUArticles/TramSerious.htm. Accessed February 7, 2018. | ||

Knisely JS, Campbell ED, Dawson KS, Schnoll SH. Tramadol post-marketing surveillance in health care professionals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68(1):15–22. | ||

Epstein DH, Preston KL, Jasinski DR. Abuse liability, behavioral pharmacology, and physical-dependence potential of opioids in humans and laboratory animals: lessons from tramadol. Biol Psychol. 2006;73(1):90–99. | ||

Raffa RB, Buschmann H, Christoph T, et al. Mechanistic and functional differentiation of tapentadol and tramadol. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(10):1437–1449. | ||

International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2013. New York: United Nations; 2014. | ||

World Health Organisation. Ensuring balance in national policies on controlled substances. Guidance for availability and accessibility of controlled medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. | ||

Section 2.2 – Opioid Analgesics, p 34. National List of Essential Medicines of India 2011. Available from: http://pharmaceuticals.gov.in/sites/default/files/NLEM.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2017. | ||

Section 1.8.2 – Opioid Analgesics, p 7. Philippines National Drug Formulary, Essential Medicines List 2008. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19477en/s19477en.pdf. Accessed July 07, 2018. | ||

World Health Organisation. WHO Technical Report Series: The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. | ||

McCarberg B. Tramadol extended-release in the management of chronic pain. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(3):401–410. | ||

Morón Merchante I, Pergolizzi JV, van de Laar M, et al. Tramadol/Paracetamol fixed-dose combination for chronic pain management in family practice: a clinical review. ISRN Family Med. 2013;1–15. | ||

International Pain Summit of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Declaration of Montreal: Declaration that access to pain management is a fundamental human right. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(1):29–31. | ||

United Nations. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs; 1961. New York: United Nations. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/pdf/convention_1961_en.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2017. | ||

Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Maurer MA. Opioid policy, availability and access in developing and nonindustrialized countries. Bonica’s Management of Pain. 4th ed. Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, editors. Baltimore: MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:194–208. | ||

Berterame S, Erthal J, Thomas J, et al. Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: a worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1644–1656. | ||

Manjiani D, Paul DB, Kunnumpurath S, Kaye AD, Vadivelu N. Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: global issues. Ochsner J. 2014;14(2):208–215. | ||

Kaye AD, Baluch A, Scott JT. Pain management in the elderly population: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(3):179–187. | ||

United Nations. World Population Ageing 2015 – Highlights; 2015. New York: United Nations. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Highlights.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2017. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.