Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 5

Training medical students in the social determinants of health: the Health Scholars Program at Puentes de Salud

Authors O'Brien M, Garland J, Murphy K, Shuman S, Whitaker R, Larson S

Received 10 May 2014

Accepted for publication 2 July 2014

Published 23 September 2014 Volume 2014:5 Pages 307—314

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S67480

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Matthew J O’Brien,1–4 Joseph M Garland,4,5 Katie M Murphy,4,6,7 Sarah J Shuman,3,4 Robert C Whitaker,1,3,8 Steven C Larson4,9

1Center for Obesity Research and Education, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 2Department of Medicine, Section of General Internal Medicine, Temple University of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 3Department of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 4Puentes de Salud Health Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 5Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 6Master of Public Health Program, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 7Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 8Department of Pediatrics, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 9Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Purpose: Given the large influence of social conditions on health, physicians may be more effective if they are trained to identify and address social factors that impact health. Despite increasing interest in teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education, few models exist.

Participants and methods: We present a 9-month pilot course on the social determinants of health for medical and other health professional students, which is based at Puentes de Salud, Philadelphia, PA, USA, a community health center serving a Latino immigrant population. This service-learning course, called the Health Scholars Program (HSP), was developed and implemented by volunteer medical and public health faculty in partnership with the community-based clinic. The HSP curriculum combines didactic instruction with service experiences at Puentes de Salud and opportunities for critical reflection. The HSP curriculum also includes a longitudinal project where students develop, implement, and evaluate an intervention to address a community-defined need.

Results: In our quantitative evaluation, students reported high levels of agreement with the HSP meeting stated course goals, including developing an understanding of the social determinants of health and working effectively with peers to implement community-based projects. Qualitative assessments revealed students’ perception of learning more about this topic in the HSP than in their formal medical training and of developing a long-term desire to serve vulnerable communities as a result.

Conclusion: Our experience with the HSP suggests that partnerships between academic medical centers and community-based organizations can create a feasible, effective, and sustainable platform for teaching medical students about the social determinants of health. Similar medical education programs in the future should seek to achieve a larger scale and to evaluate both students’ educational experiences and community-defined outcomes.

Keywords: social determinants of health, medical education, service-learning, Hispanic health

Introduction

Social conditions such as education, employment, and neighborhood conditions have a large influence on health and disease.1,2 Physicians may therefore be more effective if they are trained to identify and address social factors that impact health. Undergraduate medical education, with its primary emphasis on proximate health determinants such as specific pathogens, individual risk factors, and medical treatments, has been slow to incorporate a large body of knowledge about the social determinants of health.3,4 However, recent research has concluded that social conditions may have a greater impact on health and disease than proximate factors that have long been the focus of medical education.5–7 Although there is currently little emphasis on the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) recently acknowledged the importance of training future physicians in this area.8

There have been many efforts to integrate public health concepts into medical education, in the form of classroom teaching,9–11 field experiences,12–15 dual Doctor of Medicine/Master of Public Health degree programs,16–18 and residency rotations.19–21 However, our literature review revealed only two published programs that mention social determinants of health as a thematic focus,19,21 and few undergraduate medical education programs that incorporate teaching about the social determinants of health into their curriculums.22–24

We describe an innovative 9-month pilot course on the social determinants of health offered to medical and other health professional students. This course was developed by medical and public health faculty in partnership with a local community health center, Puentes de Salud (“Bridges of Health”), Philadelphia, PA, USA. In addition to providing primary health care to a Latino immigrant population, this organization offers several integrated service programs that address social determinants of health. Our course engages medical students directly in these service programs, while incorporating critical reflection on their volunteer experiences and didactic teaching on the social determinants of health. All course activities take place at Puentes de Salud, representing an innovative approach that puts the community at the center of participating medical students’ educational experience.

Material and methods

Course description

The Health Scholars Program (HSP) was designed as an interprofessional course to help students recognize diverse social factors that influence health and identify potential roles that health professionals can play to improve social conditions through multidisciplinary action. This course employs service-learning – an increasingly popular pedagogic tool in medical education25–27 – as its primary educational method. The HSP incorporates three linked learning activities that are central in service-learning: 1) community service, 2) didactic teaching, and 3) critical reflection. The HSP is led by volunteer university faculty and staff at Puentes de Salud.

The program and curriculum were designed by faculty and doctoral students in medicine, public health, and education. The goals of the HSP are to: 1) develop a collaborative, interdisciplinary course focused on improving the health and well-being of an underserved population; 2) expose health professions students to the social determinants of health and deepen their understanding of this topic; and 3) promote a longitudinal commitment to community health among participating students. Students are required to complete didactic and experiential learning activities over a 9-month period, which include lectures, readings, critical reflections, and community service. An outline of these course activities is provided in Table 1.

| Table 1 Health Scholars Program curriculum overview |

Lectures focus on the social determinants that impact the health of Puentes de Salud’s target population and that of similar communities nationwide. The introductory lecture focused on mechanisms through which social determinants impact individual and population health. Examples of other topics covered in the HSP pilot lectures include immigration, education, and occupation as social determinants of health. These lectures are given by participating university faculty, local practitioners, and invited national experts. To complement monthly classroom lectures, students complete a short number of readings and either attend a monthly group reflection session facilitated by course faculty or write an individual reflection focused on the program’s varied learning activities. The reflection activities encourage students to draw connections between classroom concepts and community-based experiences.28 In addition to attending lectures and completing readings and reflections, students attend training sessions provided by local advocacy organizations that are relevant to serving the target population. These training sessions focus on health care navigation for immigrants, accessing and analyzing immigrant health databases, and legislative advocacy for immigrants.

Community-based service is also an integral component of the HSP. During the 9-month program, participants volunteer for at least 8 hours per month in the Puentes de Salud clinic, its after-school tutoring program, or both. In addition, students in the HSP must also shadow at least one other of Puentes de Salud’s programs that address social determinants of health (examples in Table 2). The service component of the HSP curriculum also includes a longitudinal community project, in which teams of students design, implement, and evaluate a program to improve the health and wellness of Puentes de Salud’s target population. Students receive training from course faculty in principles of community engagement,29 consisting of relevant readings and facilitated group discussion on the topic. During meetings with community stakeholders, students explore community needs and brainstorm about potential projects to address those needs. Students then develop and implement a longitudinal project, with ongoing supervision by community leaders and the course faculty during formal monthly group sessions. Regular informal discussion among students, course faculty, and community stakeholders continues throughout the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the community projects. The first cohort of Health Scholars developed programs to lower stress among community residents and to navigate access to pediatric care for uninsured immigrant youth.

| Table 2 Puentes de Salud programs involving Health Scholars Program students |

Participants

We selected the first cohort of the HSP using an application that was sent to all area universities and medical schools. Applicants were chosen by the two course directors (JMG and SJS) based on their interest in the subject matter, previous relevant experience, and availability to participate in all course activities. This group comprised 12 students from the following disciplines: medicine (nine), public health (one), psychology (one), and Hispanic studies (one). Two-thirds of the cohort were women, and five participants were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, with half of the group consisting of minority students. These students’ formal programs of study were based at the following six institutions: Temple University, University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Bryn Mawr College.

Data collection

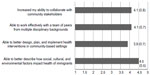

Our evaluation of the HSP consists of students’ qualitative reports collected from written reflections and a survey completed by students at the end of the program (Figure 1). On a five-point Likert scale, students reported their degree of agreement with statements about meeting HSP course goals.

| Figure 1 Student evaluations of the Health Scholars Program (Fall 2013).a |

Results

The numeric scores for each survey question, representing averages of all 12 students’ responses with associated standard deviations, are presented in Figure 1.

The following three themes emerged from medical students’ qualitative reports on the HSP: 1) this program has provided their first exposure to the social determinants of health, 2) they have learned more about the health challenges facing vulnerable populations through this program than through curricular efforts in their medical schools, and 3) this program has shaped their desire to serve vulnerable communities in their medical training and beyond. Specific comments from students include the following: “Until now, my formal education has not directly prepared me to work effectively with marginalized populations whose background is vastly different from mine … nor is it likely that my medical school curriculum will focus on addressing social determinants of health”, “There is a limit to how much you can learn from reading about social determinants of health – understanding a community and its specific health challenges comes from interacting directly with community members and building their trust”, and “The better we know our patients, the better we can serve them. This type of course should be a critical component to our formal education in any health care setting.” Participating students provided two primary suggestions for improving the HSP: 1) spend less class time on lectures and more time on facilitated group discussion and 2) provide more hands-on guidance in planning and implementing the community-based projects.

Discussion

Strengths, weaknesses, and challenges faced

We sought to develop an educational program to teach medical and other health professional students to identify and address the social determinants of health through multidisciplinary service-learning. According to our literature review, Puentes de Salud’s HSP is one of few programs that focus on the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education. The community-based setting for the HSP has enabled collaboration among students and faculty from many academic institutions in the region, and helps ensure that students’ learning activities address community needs. These defining features of our program – action-oriented, community-based, collaborative, multidisciplinary, and interinstitutional – create a unique setting to teach medical students about the social determinants of health.

The diversity of participating students with respect to academic institution, discipline, and race/ethnicity provided a rich experiential base that contributed to monthly reflection sessions. This opportunity to engage in dialogue about readings and volunteer experiences was an important complement to didactic instruction in the course. The integral involvement of community members in the development of students’ longitudinal service projects represents another strength of the HSP. Community health workers and other recognized community leaders provided guidance to students throughout the design and implementation of their community-based projects. Involving these local leaders in the course helped ensure that students’ service projects were responsive to community needs, and implicitly taught the value of iterative stakeholder input in community-based work. However, similar courses that are developed elsewhere in the future will naturally draw on different community resources and address different community-defined needs. The duration and intensity of the HSP offered students an opportunity to engage meaningfully with both the course content and the community in which the course was based.

The HSP was conducted exclusively outside of academic medical centers, which may marginalize the content for some medical students. Although this was not the case for the participants in our pilot program, integrating some learning activities into academic centers may help promote an understanding of how community and clinical contexts are related. The HSP did not include training in multidisciplinary program structures or ethics, which may help students to engage community leaders and organizations more effectively. We plan to include such background training for subsequent cohorts of the HSP. Our evaluation of the HSP, which used mixed methods, provides preliminary evidence of its effectiveness. However, our evaluation was limited by a small sample size, a narrow scope of both quantitative and qualitative components, and the lack of an experimental design. We plan to address these limitations in future research on this program. Future evaluation efforts should also explore differing perceptions of the program among medical students versus those from other disciplines.

Developing and sustaining the HSP has presented unique challenges. While recruiting volunteer faculty and teaching assistants has required little concerted effort, we have increasingly recognized the need for dedicated staff. Scheduling course activities around students’ formal educational programs based at six different institutions required more effort than was anticipated. Students’ feedback soliciting more direct guidance on community-based projects highlights the need to provide salary support to protect faculty and community leaders’ time for this purpose. Course faculty and community members might be more effective mentors on community projects if they received training on this topic. Funding constraints have limited our capacity to accommodate the large number of students who want to participate in the HSP. Also, because the course is based outside of an academic medical center and its traditional funding streams, improving and sustaining the program will ultimately require a business model that reaches beyond time-limited philanthropic support. This model may include funding from the academic medical centers whose students participate in the program.

The HSP in context

Several medical schools have recently developed undergraduate curricular elements that address the social determinants of health.22–24 Some of these published programs mention the social determinants of health as a topic that is covered in a larger curriculum focused on integrating population health22 or public health23 concepts into undergraduate medical education. Meurer et al24 describe a longitudinal program for a self-selected group of medical students that employs community-engaged learning with a primary focus on the social determinants of health. This 3-year program integrates didactic and experiential learning activities – the same curricular components used in the HSP. This course is longer in duration than ours but includes fewer monthly contact hours.

Most curricular attempts to teach medical trainees about the social determinants of health are directed on academic medical campuses or combine university-based didactic instruction with community-based experiences. Only one published program was developed jointly with a community-based organization and engages all of its trainees there, as Puentes de Salud’s program does.19 Gregg et al19 created a social medicine curriculum to teach medical residents about the social determinants of health through partnership with an organization addressing homelessness and addiction. While embedding medical trainees within one community-based organization may limit the range of their real-world exposure to the social determinants of health, it promotes a deep understanding of the population that that organization serves. In addition, engaging a number of trainees at the same site provides a collective effort to dedicate to service-based projects.

Conclusion

Our experience with the HSP suggests that partnerships between universities and community-based organizations can play a joint role in offering medical education programs on the social determinants of health. Community-based organizations understand the social forces that impact health in their communities and have experience confronting such problems. This community-informed perspective is critical and often lacking in university-led outreach efforts.30 In addition, their position outside of academia insulates community-based organizations from many of the challenges universities face when trying to address social determinants of health. Universities have limited experiential knowledge of their surrounding communities,31 structural barriers to collaborating across disciplinary boundaries,32 and financial barriers to funding multidisciplinary, community-based education programs.33 However, most community-based nonprofit organizations lack the motivation and capacity to develop medical education programs alone. Partnerships with universities can provide nonprofit organizations with both technical and content expertise of involved faculty and financial resources that offset the costs of integrating students into service programs.

Creating meaningful partnerships between academic medical centers and community-based organizations represents a unique opportunity to teach medical students about the social determinants of health – an increasingly important topic in medical education. Efforts to develop mutually beneficial partnerships between universities and community-based organizations will face challenges to sharing resources equitably, hiring staff jointly, and adequately compensating all individuals involved. However, the unique assets of each partner are necessary to help students develop meaningful theoretical and applied foundations in the social determinants of health. In addition to helping meet this curricular goal in medical education, such partnerships may also help improve the reputation of academic medical centers in the communities they serve and contribute to meaningful improvements in local health. Future courses on this topic should evaluate both participating students’ educational experiences and also community-defined outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Thomas Inui and Judy Shea for their thoughtful review and comments on previous drafts of this manuscript. This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (K23-DK095981 O’Brien).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work, financial or otherwise.

References

Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt K, DiMaggio C, Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1456–1465. | |

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. | |

Hernandez LM, Munthali AW, editors . Training Physicians for Public Health Careers. 1st ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. | |

Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;(35):80–94. | |

McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):78–93. | |

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. | |

Schroeder SA. We can do better: improving the health of the American people. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221–1228. | |

Association of American Medical Colleges. Behavioral and Social Science Foundations for Future Physicians. Report of the Behavioural and Social Science Expert Panel. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2011. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/download/271020/data/behavioralandsocialsciencefoundationsforfuturephysicians.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2014. | |

Dannenberg AL, Quinlisk P, Alkon E, et al. US medical students’ rotations in epidemiology and public health at state and local health departments. Acad Med. 2002;77(8):799–809. | |

Finkelstein JA, McMahon GT, Peters A, Cadigan R, Biddinger P, Simon SR. Teaching population health as a basic science at Harvard medical school. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):332–337. | |

Rosenberg SN, Schorow M, Haynes ML. Bridging the gap between clinical medicine and public health: an experimental course for medical students. Public Health Rep. 1978;93(6):673–677. | |

Carney JK, Hackett R. Community-academic partnerships: a “community-first” model to teach public health. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008;21(1):166. | |

Carpenter DE, Dobs-Haske L, Foldy S. A public health sub-curriculum of a pediatrics clerkship. Acad Med. 1997;72(5):436–437. | |

Paterniti DA, Pan RJ, Smith LF, Horan NM, West DC. From physician-centered to community-oriented perspectives on health care: assessing the efficacy of community-based training. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):347–353. | |

McIntosh S, Block RC, Kapsak G, Pearson TA. Training medical students in community health: a novel required fourth-year clerkship at the University of Rochester. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):357–364. | |

Boyer MH, Madoff MA, Bennett AJE, et al. Tufts’ 4-year combined MD-MPH program: a training model for population-based medicine. Acad Med.1992;67(6):363–365. | |

Chauvin SW, Rodenhauser P, Bowdish BE, Shenoi S. Double duty: students’ perceptions of Tulane’s MD-MPH dual degree program. Teach Learn Med. 2000;12(4):221–230. | |

Harris R, Kinsinger LS, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Viera AJ, Dent G. The MD-MPH program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):371–377. | |

Gregg J, Solotaroff R, Amann T, Michael Y, Bowen J. Health and disease in context: a community-based social medicine curriculum. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):14–19. | |

Klein MD, Kahn RS, Baker RC, Fink EE, Parrish DS, White DC. Training in social determinants of health in primary care: does it change resident behavior? Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):387–393. | |

Schubert CJ, Volck B, Kiesler J, Klein MD. Teaching advocacy to physicians in multicultural settings. Open Med Educ J. 2009;(2):36–43. | |

Chamberlain LJ, Wang NE, Ho ET, Banchoff AW, Braddock CH, Gesundheit N. Integrating collaborative population health projects into a medical student curriculum at Stanford. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):338–344. | |

Geppert CM, Arndell CL, Clithero A, et al. Reuniting public health and medicine at The University of New Mexico School of Medicine Public Health Certificate. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S214–S219. | |

Meurer LN, Young SA, Meurer JR, Johnson SL, Gilbert IA, Diehr S. The urban and community health pathway: preparing socially responsive physicians through community-engaged learning. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S228–S236. | |

Buckner AV, Ndjakani YD, Banks B, Blumenthal DS. Using service-learning to teach community health: the morehouse school of medicine community health course. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1645–1651. | |

Seifer SD. Service-learning: community-campus partnerships for health professions education. Acad Med.1998;73(3):273–277. | |

Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Washington, DC: Liaison Committee on Medical Education; 2011. Available from: http://www.lcme.org/publications/2015-16-functions-and-structure-with-appendix.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2014. | |

Cashman SB, Seifer SD. Service-learning: an integral part of undergraduate public health. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(3):273–278. | |

Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. | |

Carney JK, Maltby HJ, Mackin KA, Maksym ME. Community–academic partnerships: how can communities benefit? Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S206–S213. | |

Butin DW. The limits of service-learning in higher education. Rev High Educ. 2006;29(4):473–498. | |

Hall P, Weaver L. Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: a long and winding road. Med Educ. 2001;35(9):867–875. | |

Kezar A, Rhoads RA. The dynamic tensions of service learning in higher education: a philosophical perspective. J High Educ. 2001:148–171. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.