Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Towards Examining the Link Between Workplace Spirituality and Workforce Agility: Exploring Higher Educational Institutions

Authors Saeed I, Khan J , Zada M , Ullah R, Vega-Muñoz A , Contreras-Barraza N

Received 27 October 2021

Accepted for publication 23 December 2021

Published 7 January 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 31—49

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S344651

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Video abstract presented by Imran Saeed.

Views: 242

Imran Saeed,1 Jawad Khan,2 Muhammad Zada,3 Rezwan Ullah,4 Alejandro Vega-Muñoz,5 Nicolás Contreras-Barraza6

1IBMS, The University of Agriculture Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan; 2Department of Business Administration, Iqra National University, Peshawar, Pakistan; 3Business School Henan University, Kaifeng, Henan, 475000, People’s Republic of China; 4Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, 100081, People’s Republic of China; 5Public Policy Observatory, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Santiago, 7500912, Chile; 6Facultad de Economía y Negocios, Universidad Andres Bello, Viña del Mar, 2531015, Chile

Correspondence: Muhammad Zada

Business School Henan University, Kaifeng, Henan, 475000, People’s Republic of China

Tel +8618595590712

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Spiritual inherited employees quickly shift to new changes that occur very quickly in our daily lives in different ways. We are inspired by the dynamic changes in our daily lives due to the Covid 19 situation, an urgent need to specify the shift from the traditional approach to the agile approach during a pandemic. This study aimed to figure out the effect of workplace spirituality on workforce agility; further, this study underpinning spillover theory to examine the role of job involvement as a mediator.

Methods: This study investigates a sample of 236 teaching and administrative staff working in public sector institutes located in Peshawar, Pakistan. For data analysis, we used SPSS v. 25, and for model fitness, we used AMOS version 22. Furthermore, we used Process Hayes (Model 4) to test the theoretical model and research hypothesis for mediation.

Results: This unique study offers a paradigm in which spirituality in the workplace substantially influences the agility of teaching and administrative professionals by positively mediating the effects of job involvement.

Discussion: An in-depth examination of the literature showed that no prior research had studied the connection between WPS, job involvement, and workforce agility. Furthermore, there is very little research regarding WPS and its connection with other components in the Covid 19 scenario. The current study was a modest attempt to address this gap in the literature. This research has succeeded in making substantial additions to management literature.

Keywords: workplace spirituality, workforce agility, job involvement, workforce performance, spillover theory

Introduction

In a highly uncertain economic climate, organizations nowadays confront intense competition from domestic and international firms delineated by diligent work, a fast working environment, creative tactics, and the Covid 19 pandemic. As a result, businesses are constantly developing new methods to combat unpredictable changes in the workplace.1 Employees need to be agile to adopt new ways to a fast, demanding, and changing business environment,2,3 while employees are expected to be active, robust, and forward-looking.4 Potential researchers to conduct their investigations under these circumstances are compelled to consider workforce agility. Organizations are well aware that they must continuously adapt to changes to remain in today’s competitive and dynamic settings.5 This issue has led academics to develop agility in the workplace in response to rapid environmental changes.6

Workforce agility is a swift and active adaptation to unpredictable and unexpected changes in organizational components.7 Workforce agility has two main characteristics: (a) the most effective and timely identification and realization of opportunities in the shortest possible time and (b) the most effective and timely response to dynamics and risks in the shortest possible time.6,8 It concentrates on getting the finest for the organization and providing everything concrete and promptly. In the agile approach, employees value their colleagues and their interactions.9 Few studies have examined employee agility from a conceptual viewpoint, especially in education units.10 Learning organizations require teachers who are willing to learn and progress rapidly while maintaining a pleasant atmosphere, especially during Covid 19. Teachers face difficulties while attending online classes, such as increased absenteeism, students’ concentration, internet issues, and space for taking classes during pandemics.11 Organizations require delighted and energetic workers to survive, handle, deliver and cope with unforeseen situations.11,12

On the other hand, employees are concerned, discouraged, and uneasy due to economic downturns and crises, especially during Covid 19.13 These uncertainties encourage workers’ spiritual demands and seek significance in their jobs. Therefore, academics must realize those spiritual elements must be included in an educational environment. Spirituality among teachers must be nurtured to enhance their performance and wellbeing, leading to more agility in complex situations.14,15 Furthermore, studies in the education sector found that lecturers, educational managers, and higher education sector students are key players of workplace spirituality.16 The concept of WPS in the higher education sector has contributed to the literature.17,18 In HEIs, teaching staffs are mainly concerned with positive associations with students and colleagues. Teaching staff are concerned with their personal beliefs and work behaviours which contribute to improving students’ human impending.19 Pakistan is a collectivist culture, and people have strong bonds with one another.20 In Pakistani culture, youngsters follow their elders and respect teachers, leaders, and managers.21 On the basis of the above justification, this study will contribute more in the Pakistani context. Job satisfaction and employee engagement have positive effect on workforce agility in transportation administrative staff.22 WPS has significant effects on administrative employees’ organizational citizenship behavior in the banking sector.23 A similar study conducted by Jeon and Choi24 found that administration staff WPS has a significant effect on organizational commitment.

The development of a country is impossible unless the potential and prominence of teachers are vital to a social system. Teachers who are content with their employment demonstrate a commitment to their organizations.13 It is fascinating to know why spirituality plays a part in our working lives. Studies on spirituality regarding work attitudes have increased.25 Most studies have shown a link between workers’ spiritual aspects and workplace behavior. While quantifying spirituality is a challenging and dubious job, research in this field is progressing rapidly. In the present business context, organizations are always searching for methods to surpass their opponents, to which outstanding employees are unavoidable. This makes it realistic for organizations to investigate spiritual elements by building meaningful and flexible workplaces.15

Spirituality in the workplace has been acknowledged as a unique approach to improving employee performance. Laabs26 stated that “the spiritual approach causes a change in the values at work to promote collaboration rather than fear at work.” A particular pattern of spiritual guidance emerges when the workplace may provide appropriate conditions for professionals, where they share their behavior and attitudes to foster moral values and a sense of meaning in their work. Spirituality in the academic workplace thus needs to foster a teaching community and administrative professionals with persistence, assertive behaviour, and agile thinking to achieve their organization’s objectives, particularly in the Covid 19 scenario. The education sector is one of the agile sectors in the world where, on a regular basis, innovation in technology changes, new methods of teaching direction change, and pedagogical methods also change.27 All these changes are possible when there is agility in the teaching staff of the education sector.18 This “revolution in the measurement of collective human behaviour”28 effects the mindset of teaching staff, who are gradually necessary to become more agile. Agile workforce (lecturers) can create a positive attitude toward new challenges in schools and HEIs.29 A study was conducted by Soliman, Di Virgilio30 in the education sector in Portugal and Italy. They found that WPS had a positive and significant relationship with the W.F.A. Furthermore, this study calls for future research that there is a dire need for intervening mechanics between WPS and W.F.A. among lecturers of H.E.I. Paul, Jena13 studied spirituality and agility in the workplace and suggested avenues for further research. We expand the model (see Figure 1) in the lens of spillover theory by adding job involvement as a mediator in the Pakistani context between WPS and workplace agility. The expected result would contribute to the agility of education and administrative professionals in higher education institutions in Pakistan.

|

Figure 1 Proposed study model. |

Literature Review

Workforce Agility (W.F.A.)

Aside from the fact that workforce agility is critical in today’s changing business climate, there is no precise theory or definition of workforce agility.31 Many academics and scholars have described workforce agility as a skill or behavior needed by employees in a rapidly changing global economy. Kidd7 noted that worker agility includes two major components: the capacity of the workforce to react appropriately and promptly to changes and the strength of the workforce to consider threats as opportunities. Zhang and Sharifi32 explain that the agile workforce can overcome market turbulence by harnessing the advantages of these dynamic circumstances occurring in the corporate culture. Plonka33 noted that agile employees have a friendly approach toward learning, self-development, excellent troubleshooting, easy adaptation to changes, creative ideas, and a constant acceptance of new tasks.

Kidd7 stated, agility is the ability to respond quickly and proactively to both anticipated and unforeseen events in a company’s environment.

W.F.A. was previously described from a behavioural point of view34. Saeed, Khan35 defined agile individuals as proactive, adaptive, and resilient in their actions and decisions. Predicting difficulties associated with change is called proactive behaviour, starting actions that help address these issues. Adaptive behaviour relates to professional adaptability, which can manage numerous responsibilities in different teams concurrently. Resilient conduct takes a favorable view of changes, new ideas, sophisticated technologies, broad-based thinking and acceptance, contradictions in beliefs and methods, stress management and abnormal situations.36

Workplace Spirituality (WPS)

In the last decade, management scholars have been more interested in defining the notion and significance of spirituality in an organizational setting. Several scholars have offered different definitions and thoroughly contextualized WPS from organizational and individual perspectives.24,37 The presence of spirituality in the workplace implies having a framework of values and a corporate culture that reflects inner life, openness, care, interaction, respect, humility, compassion, and transcendence from the organization’s perspective.38 From the individual’s point of view, spirituality at works “the conscious awareness and manifestations of one’s spirituality” at the workplace.39 It is conceived as a multidimensional approach seeking meaning and purpose in life.40–42 Pioneering research on workplace spirituality, which included the transcendental component, found seven different elements of WPS.25

Petchsawang and Duchon43 workplace spirituality is defined as having feelings of grateful to others, having inner satisfaction to perform job roles and having passion towards organizational values.

The literature available on W.S.P. is replete with various definitions of WPS. Kinjerski and Skrypnek44 had up to 70 W.S.P. definitions, but none were widely accepted and unanimously recognized by scholars. A Few W.S.P. definitions are presented as follows:

|

|

Lodahl48 and Kejnar49 developed the term job involvement. According to Kanungo,50 jobs that have a greater capacity to fulfill their immediate needs are more likely to positively affect one’s job involvement. Furthermore, he said that people considered extremely engaged in their jobs to view their jobs as an important part of their identity. According to Joiner and Bakalis,51 job involvement is defined as the degree to which individuals inside an organization are engaged, connected, and concerned about the organization’s goals and mission. Individuals who are very involved in their jobs are less likely to consider leaving their jobs, and they contribute to the long-term success of their employers.51–53 According to Kanungo48 findings, job involvement indicates that employees have a cognitive connection with their jobs.

According to Kanungo,48 workers are the driving force behind a company’s success. Employee-related outcomes must first be achieved in order for a company to meet its objectives. Employees’ performance may run smoothly if they are paid accordingly with their expectations, get training and development, work in a positive culture, receive career planning support, and receive feedback from the organisation.

Mudrack54 found that when employees have significant job engagement, they see their jobs as making way to their identities, life objectives, and interests. Therefore, greater employee involvement leads to higher job satisfaction and loyalty to the company.55 According to Chen and Chiu,56 individuals who have a high level of involvement in their professions have self-confidence and identity in their work. Sarros, Cooper57 highlighted the apparent link between job involvement and intellectual activity. Paullay, Alliger58 defined job involvement as an employee’s deeper interest in their present employment. Thus, job involvement refers to a person’s psychological connection to the kind of work they do.59

Workforce Performance (W.F.P.)

Developing and maintaining an effective and competent workforce is essential for an organization’s stability. According to Van Horn and Fichtner,60 skilled staff and other organizational factors contribute to the success of an organization; therefore, maintaining its capacity to remain efficient in a highly competitive economic environment is essential. To achieve effective performance, it is necessary to have well-trained staff. Workforce performance is related to organizational performance and quality.58 It provides the foundation for an organization’s success.2,61

Furthermore, small misunderstandings between employers and employees may create a great deal of aggravation and have serious consequences for employee performance, attrition, and the desire to leave the company. Papis62 states that it is essential to understand the workforce if organizational goals are achieved. It was observed in a study of Scottish Hostel Assistants that knowing the workforce is important for work to be done effectively, systemically, and professionally. A balanced environment and workforce identity are required for work to be done effectively, systemically, and professionally.2,62 By 2030, the United Nations predicts that between 15 and 24 years of age, there will be about 1.3 billion people on the globe. Africa, proving to be a fountain of youth globally, has the world’s top ten nations with the highest proportions of youthful people. Nigeria, Somalia, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) are those countries that come among the top ten list. Niger is the world’s youngest nation, with almost half of the population under 15. The figures for 2021 show that the Niger workforce (49.8%) is considered young and energetic, compared to industrialized nations such as China (17.8%), the United States (18.5%), Japan (12.6%), and Great Britain (17.7%). Young nations have a ton of potential in front of them. A younger population implies a larger future workforce, as well as greater possibilities for innovation and development. At the same time, Africa’s internal markets expand in terms of labor supply, innovation, and prospective customers. Still, this continent faces specific difficulties in corruption, political instability, and unemployment, which are all possible obstacles to success for the continent’s Gen Z population, especially in Africa.63

Formation of Hypothesis and Theory Underpinning

Spillover Theory

According to the spillover theory, an effect always spreads; therefore, when employees are spiritually motivated, they become more agile and positively engaged in their jobs. According to spillover theory, all of the relationships suggested in the model are supported by the theory. The idea of spillover describes sentiments, emotions, and behavior and its effect from one domain to another. Positive and negative spillovers are possible, depending on the circumstances. Unwanted spillover occurs when procedures in one area that are accepted over time hinder the fulfillment of difficulties in a subsequent field from occurring. On the other hand, positive spillover occurs when practices carried over from one field improve performance in a subsequent area of influence64 Spillover’s theory65 suggests that our desires, emotions, and professional lives are not cleanly categorized, and their consequences extend over a wide range of sectors of life. Initially, this idea was used to study a person’s quality of life and work-life balance.66 In this research, spillover theory investigates WPS and its impact on employees’ professional lives. Employees have a more favorable perception of their workplace, and their belief in their ability to contribute to the company is reinforced, motivating them to participate in more agile ways.

Similarly, meaningful work, a sense of belonging, and alignment with company values may all contribute to making the workplace a vibrant and enjoyable place. This inner awareness affects one’s attitude toward doing a job favorably. People with an inner spiritual life are more inclined to utilize hidden resources to function thoroughly. Interestingly, spirituality improves the workforce’s agility via the mediating impact of job involvement.

Workplace Spirituality and Workforce Agility

Spirituality at work is an official slogan for many business organizations and the education sector. Academic institutions have launched unique, innovative, and functional initiatives to meet competitive market needs. The main goal is to provide a flexible learning environment where students may discover new things and teachers can comprehend and react to their students appropriately.27,67 Executives and upper management should be adaptable, but workers at all levels should be as well.2 It becomes more important to educate employees to find purpose in their work responsibilities to deal with crises and embrace changes autonomously.68 It may be accomplished in many ways, including (1) retaining experience and competencies, (2) strengthening human resources, (3) giving more weight to human values, (4) collaborating, and (5) encouraging experimentation, all of which are characteristics of spirituality in the workplace.13,69 According to the results of Paul, Jena,13 we can conclude that spiritually oriented employees are always more agile than their non-spiritual peers in the workplace. Professional workers who have spiritually inherited their positions can overcome any difficulties and view them as an even more amazing chance to advance their careers by making the required changes.70,71

H1: There is a positive relationship between WPS and workforce agility

Workplace Spirituality and Job Involvement

There is substantial evidence of a link between WPS and job involvement.72 According to Milliman, Czaplewski,73,74 WPS positively impacts employee job involvement. Even though75 identified a direct link between WPS and job involvement, they found no relationship between individual spirituality and work-related results. A previous study defined job involvement in the workplace based on the degree of psychological bonding.50,76,77

Individuals can perform their job roles more effectively when working in a psychologically secure setting.78,79 According to Brown and Leigh,80 the development of inner awareness among workers is an unavoidable characteristic of a spiritual environment that allows them to engage in meaningful tasks. Workplace spirituality has proven to be beneficial for employee job involvement.80 Until now, the study performed by Kolodinsky, Giacalone75 has been the most thorough investigation of the relationship between spirituality and job involvement. They discovered that having spirituality in the workplace is linked to a higher level of job involvement.

H2: There is a positive relationship between WPS and job involvement

Job Involvement and Workforce Agility

Job involvement is essential to ensure that the workforce is agile.81 Research conducted by Muduli82 proved that employee involvement plays a significant role in workforce agility. According to Sumukadas and Sawhney,83 employee involvement is a predictor of agility in the workplace itself. A group of academics developed agility in 1991 to help organizations adapt to rapid environmental changes.82,84 Several approaches for generating and fostering worker agility have been suggested in the literature. A few empirical studies have been conducted on the effect of job involvement practices on the agility of a company’s employees.83,85 Muduli,5,82,83 found that low-order employee involvement activities enhance workforce agility more effectively than high-order employee involvement practices found that employee’s psychological and emotional presence is an essential possibility of promoting agility. Employees’ ability to make decisions independently is one of the most important factors influencing workforce agility.86 Job involvement improves the motivation of the workforce to accept, manage and adjust to organizational changes, as they possess better knowledge and relevant skills.87,88 Limited participation may reduce employee’s readiness to embrace change.89

H3: Job involvement is positively and significantly related to workforce agility

Job Involvement as a Mediation

Precedents for job involvement have been established based on an organization’s capacity to fulfill the requirements of its employees.50 Trott III90 states that those who find significance in their job roles reflect a profound sense of purpose and meaning in their jobs. Forming a constructive, ongoing engagement or relationship with others that are essential elements of a community is more likely to engage employees in their jobs, develop, learn, and experience agility. Spirituality in the workplace motivates employees intrinsically, resulting in greater job involvement.91,92 Organizations that generate a spiritual environment are more attentive to the purpose and values of their employees in t). According to Milliman, Czaplewski,73 a strong sense of community and corporate values are linked to employees’ satisfaction and involvement in the workplace. Kolodinsky, Giacalone,75,93 showed a strong link between WPS and job involvement. Muduli82 showed that job involvement is essential to workforce agility. Employees who are spiritually driven and positively involved in their jobs react swiftly to changes, allowing them to survive and flourish in a competitive working climate.83

H4: Job involvement positively mediates between WPS and WFA

Workforce Agility and Workforce Performance

Agile workers may achieve several benefits, such as high-quality job roles, better services, high performance, practical learning possibilities, and an optimal workforce.2,94 According to recent research findings of Goodarzi, Shakeri,95 there is a significant correlation between worker agility and performance. A study conducted by Sumukadas and Sawhney83 found that agile employees contribute to handling decision-making processes and improve strategic planning within organizations. Ultimately, workforce agility is a consequence of workers’ ability to adapt, respond swiftly, and be prepared to meet new demands as they emerge in the workplace.96,97 As stated in the introduction, the agility of the workforce is especially essential to the success of all organizations. Varshney and Varshney,2,31 stated that workforce agility has a beneficial effect on workforce performance. We incorporated a hypothesized connection between employee agility and performance in our model.

H5: There is a positive relationship between workforce agility and workforce performance

Research Methodology

Research Design

The nature of this study was quantitative, and data were collected using standard questionnaires. During COVID 19, it was difficult to collect data from other organizations, so we chose the education sector for this study. During Covid 19, the education sector was the only sector in Pakistan that was fully operated, and faculty members were taking classes online. Pakistan is a third-world country where basic facilities are not available to the people, but the education sector did not stop their learning process during Covid 19. Therefore, teaching and administration staff were involved in performing their duties. For this reason, we chose Peshawar.

Population and Sample

The study target population was the teaching and administration staff of six public institutes in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. It was not easy to collect data from public educational institutes due to Covid 19 situation in the country. Teachers were taking classes online due to the closure of institutes, and only 50% of the administrative staff were allowed to be in office as per government notification. For data collection, 60 employees (60 × 6 = 360) from each institute were targeted. Convenient sampling techniques with a proportion allocation method were used to collect data from the employees. Due to Covid 19, it was impossible to collect data from the whole population; therefore, we selected only those employees who were conveniently available to respond. The survey method was used to collect data from respondents. In this study, we designed proper questionnaires and sent them through email, different WhatsApp groups, Facebook, and some were contacted physically to collect data. The details of the response rate and questionnaire are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2. The data were collected in three waves, the best technique to minimize common method bias.98 In the first wave, the data were collected regarding demographic variables and WPS; the attrition rate was 36.06%. After 15 days, data were collected regarding job involvement (attrition rate was 31.45%). In the third wave, the data were collected regarding workforce agility and workforce performance; at this stage, the attrition rate was 41.22 (see Table 2 and Figure 3). Three hundred sixty employees were targeted; in the end, we received a response of 236 employees (65% of total) (see Table 1). The anticipated response rate of the convenience sample method in the above computation was higher than 60%, as suggested by Kiess and Bloomquist.99

|

Table 1 Distribution of Questionnaires |

|

Table 2 Data Attrition |

|

Figure 2 Graphical presentation of the target population. |

|

Figure 3 Graphical presentation of questionnaires attrition. |

Instruments

Workforce Agility (W.F.A.)

Sherehiy100 developed a 26-item scale of workforce agility. The scale consists of three subscales: proactively, adaptability, and resilience. Proactive conduct involves feelings of readiness. The adaptive component refers to the capacity of a person to adjust to a new environment, and resilience refers to working well under duress. The alpha value of this study was 0.82.

Workplace Spirituality (WPS)

Spirituality at work was assessed using the measures established by Ashmos, Duchon,101 and Milliman, Czaplewski73 used 13 questions to evaluate spirituality at work. This tool has three subscales: meaningful work-five items; a feeling of community - this scale contains five items; Milliman et al found a spirituality scale alpha value of 0.88. Examples are: “I feel pleasure at work,” “I feel part of a community,” and “I feel good about my company’s principles.” The scale includes a 5-point Likert response style from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Job Involvement (J.I.)

Lodahl and Kejnar49 used the scale created to assess job involvement. For this study, 16 items of this scale were adapted. It had an alpha value of 0.76. The examples are: “I will remain overtime even if I’m not paid; in my life, the greatest pleasure doesn’t come from my work.”

Workforce Performance (W.F.P.)

Two significant aspects of individual job performance were questioned by participants: task performance and contextual performance. Koopmans, Bernaards102 modified the measurement of task performance and contextual performance. All 17 items were evaluated on a Likert 5-point scale. The alpha reliability was 0.86.

Demographic Statistics

Table 3, shows demographic statistics. The male employees filled the maximum number of questionnaires (88% of the total employees). Due to the Covid 19 situation, most female employees were working from home (50% staff as per Government Notification). Most questionnaires were completed by employees who were experienced with a service of 6–10 years. Master and M.S. /Phil/Ph.D. qualified employees were 61% and 41% of the total respectively (see Figure 4).

|

Table 3 Demographic Details |

|

Figure 4 Graphical representation of demographic variables. |

Measurement Model

Items with a low loading factor (at least.50) for each latent variable should be removed based on the results of the C.F.A. Table 4 lists the eliminated items and standardized loading factor of each latent. In addition, after removing certain items from every construct, the table shows the surviving objects and their standardized loading factor. While the factor load value for the other items was substantial and exceeded 0.5, the convergent validity of each construct was verified.103

|

Table 4 Survivor and Removed Items After Each Latent Variable |

Confirmative Factor Analysis of Each Variable

After the improper elements were removed, the measuring model was verified for each variable. For all latent variables, Table 5 shows the outcomes of C.F.A. of each variable. Table 5 reveals that the measurement model CMIN/DF value of 2.4 which is acceptable as < 2 or 3 is in excellent agreement.104,105 The GFI, CFI, RMR, AGFI, and RMSEA values were 2.3, 0.93, 0.94, 0.04, and 0.92, respectively, indicating excellent fitness.106 RMSEA was calculated at 0.05, indicating a good match; Steiger107 recommended that RMSEA be less than 0.07. Hu and Bentler108 say RMSEA values of 0.08 indicate an excellent match. Because of this, as shown in Table 5, the overall measurement model of the study was well-fit. The Goodness of fit index (G.F.I.), AFGI, R.M.R., comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) in Table 5 indicate the goodness of fit indices; they all fall within the acceptable range. According to Table 6, the C.F.A. was confirmed for research model 1. The measurement model initially had somewhat higher acceptable values, which was not good. Obtain the model’s fitness; some indicators have been removed showing a lower load factor after running C.F.A. Some alteration indices were created, which were required in AMOS to suit the model. The measurement model is displayed in Figure 5, indicating that the theoretical model is supported by empirical data drawn from the sample (n = 236).

|

Table 5 The Results of the Goodness of Fit Indices |

|

Table 6 Fit Indices for C.F.A. of a Research Model |

|

Figure 5 Model fitness model. |

Confirmative Factor Analysis of Model 1

Data Analysis and Results

Validity and Reliability

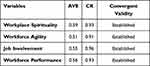

Table 7 presents a descriptive analysis of all variables, including the mean, standard deviation, and correlation matrix. For WPS, WFA, JI, and WFP mean values were 3.5, 3.6, 3.5, and 3.5 with standard deviation values of 0.66, 0.44, 0.69, and 0.70 respectively. The correlation matrix for all research variables was satisfactory, and all constructs had values less than 0.90, indicating that multicollinearity did not create issues in the study.110 The variables’ reliability was determined using the Cronbach Alpha coefficient, which was satisfactory. As shown in Tables 8 and 9, Constructs validity was determined using C.F.A. in AMOS V. 22, widely regarded as an acceptable method for determining construct validity by researchers.111 Campbell and Fiske112 defined construct validity as having two components: (a) convergent validity and (b) discriminant validity. “Confirmatory factor analysis examines the degree to which measures of a latent variable share their variance and how they vary from other measures”.113 As indicated in Table 8, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (C.R.) computed convergent validity measures. In the range of acceptable values of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, AVE and C.R. values were observed.114 Hu and Bentler108 claimed to fulfill convergent validity, the loading must be higher than 0.5. Thus, the convergent validity of all variables was determined. To demonstrate discriminant validity (see Table 9), the squared correlation between all constructs must be smaller than the average value of each construct examined (Walsh et al 2009). The squared correlations between all constructs were then compared to the AVE values for each variable. In Table 8, the AVE values are greater than the squared correlations. Consequently, the discriminant validity of the constructs was also established.

|

Table 7 Mean, Std. Deviation, Reliability and Correlation Matrix (n = 236) |

|

Table 8 Convergent Validity Analysis |

|

Table 9 Discriminant Validity Analysis |

Hypotheses Testing

Direct Relationship

To determine the effects, we used SPSS Version 25 for the regression analysis. As shown in Table 10, WPS positively correlated with workforce agility (R2 = 0.60, β=0.50, t=19.81, p < 0.000), and the study’s first hypothesis was significant. Workplace spirituality was positively correlated with job involvement (R2 = 0.50, β= 0.73, t= 15.33, p < 0.000), thereby endorsing the second hypothesis. Likewise, the third hypothesis was confirmed by a positive correlation between job involvement and workforce agility (R2 =0.43, β=0.41, t=13.48, p < 0.000). Workforce agility in Table 11 shows a positive relationship with workforce performance, supporting the fifth hypothesis of the study (R2 =0.31, β=0.91***t=10.26, and F= 105.27).

|

Table 10 Direct and Indirect Effects |

|

Table 11 Workforce Agility and Workforce Performance |

Mediation Analysis

The Hayes Model 4 (SPSS V. 25) was used for the mediation study using the bootstrapping method. This technique is also based on the methods developed by.115 The significance of the indirect impact was identified by the 2000 iteration bootstrapping method as indicated by Preacher and Hayes.116 WPS is indirectly linked to workforce agility through job involvement (effect = 0.0993, BootSE=0.0325, BootLLCI=0.0393 and BootULCI=0.1654), showing partial mediation (see Table 10).

Conclusion and Discussion

Discussion

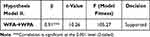

This study comprises four direct relationships, all of which have significant and positive links with others. Our first hypothesis demonstrates a constructive, positive effect of WPS on W.F.A. These hypothesized results were consistent with the findings of Paul, Jena.13 The study’s second hypothesis illustrates that WPS and the mediating variable (J.I.) are significantly linked, which is supported by.72,77,117,118 The third hypothesis is that job involvement plays a positive role in workforce agility. This hypothesis is aligned with the results of Natapoera and Mangundjaya.87 The hypothesized relationship between W.F.A. and W.F.P. is positive and significant, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.2,6 The fourth hypothesis of this study creates a positive and significant link between WPS and W.F.A. via J.I., as suggested by30 UTAMI, Sapta 119,120 (see Figure 6).

|

Figure 6 Study model results. Note: ***Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed). |

Conclusion

Creating a flexible organization comprised of agile people is viable in an unexpected and dynamic corporate environment. An agile workforce includes employees who are upbeat, adaptable, flexible, adventurous, and versatile in their job roles. They approach new knowledge with an open mind to further their personal growth while improving analytical abilities and adapting to a constantly changing work environment. Their openness to new ideas and technology and their willingness to assume new tasks and obligations distinguish them from others. Job involvement includes intrinsic drive and self-efficacy, contributing to the workforce’s resilience and strength by increasing their sense of self. Academic institutions will be unable to remain nimble unless they have a community of genuinely motivated teaching professionals. Teaching effectiveness improves when teachers experience inner pleasure from their jobs, maintain positive relationships with students and colleagues, have a sense of purpose at work, and make independent choices, which results in emotional enrichment for both students and teachers. Teacher’s performance will increase when an ethical corporate culture, mainstream practices, and a varied student community are in place.

To attain the agility needed for employee success, we must rethink our workforce due to these developments. Regular practitioners of spiritual methods, such as yoga and meditation, may enhance their physical and mental flexibility, beneficial for both employers and employees. They learn to concentrate better at work, be more attentive in the classroom, and acquire the spiritual consciousness required to address various issues delicately. Yoga and meditation are two such techniques. Employees with spiritual ancestry can listen to virtually anything without losing their anger or self-confidence in the meantime. WPS instills a sense of compassion in teachers, which allows them to manage children effectively. Thus, via job involvement, spiritual components in the workplace contribute to workplace agility to manage changes in the workplace.

Future Managerial Implications

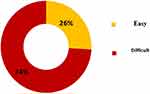

Pakistan was among the first nations to implement extensive institutes closures in response to Corona virus 2019121 Some important questions to be answered responding to the Covid 19 pandemic and its changes in our daily life. When it comes to teaching problems that instructors may encounter during online lectures? Will children’s education be harmed as a result of institutions’ closures? The authors of this note provide an overview of how WPS impacts workforce agility in the face of a pandemic. The HEC encouraged university administrators to begin offering online classes. It has been successful in various nations. Pakistan faced many obstacles, as only 36.86% of the population had access to the Internet in 2019, according to a recent study by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority122 A survey was conducted in fifty-five universities from 407 students in 11 cities throughout Pakistan to continue online education. 71% of the target population did not support online education; 29% of students support online education (see Figure 7). Second, 74% of students find online education very difficult, and only 26% of students find it easy survey (see Figure 8).123

|

Figure 7 Students reaction to online education. Note: Gallup Pakistan Survey on Digital Learning and Online Education during COVID-19, April 2020. |

|

Figure 8 Students response to online education. Notes: Gallup Pakistan Survey on Digital Learning and Online Education during COVID-19, April 2020. |

The Higher Education Commission (H.E.C.) remained pragmatic throughout the crisis, providing technical support to institutions and producing a series of policy advice documents on online education. These suggestions are included in several documents and are available on the H.E.C. website. Schools and universities worldwide have discontinued in-person instruction in favor of online education as part of a large global experiment in interactive learning. Respond to Covid 19 situation, H.E.C. must provide support in terms of internet facilities, laptops or smartphones, electricity problems and space conditions. 41% of students attend online classes while sitting with to 2–3 people.123

Without workforce agility, organization flexibility is impossible. Organizations need to reinvent themselves to arrange resources flexibly in response to changing circumstances.82 By hiring high-quality teachers and sustaining better teaching standards, higher education institutions (H.E.I.s) are developing and striving to offer ample possibilities for teaching and administrative professionals’ wellbeing and professional growth to attain academic success.27,124 Teaching professional development is defined as “actions that improve an individual’s skills, knowledge, competence, and other teacher characteristics.” At higher educational institutions, faculty development may take a variety of forms, from official to informal. It can be designed to be accessible by inviting external experts to participate in targeted skill development workshops, conferences, and symposiums, organize lectures featuring eminent figures from the teaching and research fields or establish formal programs taught by corporate personnel. Long-term benefits will accrue to the organization due to faculty development and administrative development programs, as well as trips to other renowned academic institutions for collaborative planning, mentoring, and best practice exchange.

In terms of spirituality, the connections between teachers and students change as they learn from one another in a classroom setting. Teachers must behave as facilitators rather than as providers of pertinent knowledge and learning tools to ensure that students learn effectively. Presently teaching professionals make good use of class time by experimenting with different teaching pedagogies and techniques and improving their oratory skills. Within the classroom, students and instructors often interact, enabling teachers to understand each student. Introvert students collaborate online to engage in class discussions and gain a more global viewpoint. Ignacio Estrada’s statement is very pertinent in this context: “If a kid cannot learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn”. As a result, instructors must continuously develop themselves in a variety of ways. Academic institutions must provide competitive salaries, internet facilities, research grants, and fellowships for further study. Educators may increase their activity level by embracing new teaching assignments and other challenges by cultivating an agile attitude. Teachers benefit from opportunities to teach at foreign institutions and research in other developed countries by establishing faculty exchange programs with other educational institutes. Teachers may improve their spiritual awareness and self-awareness by regularly attending wellness programs, spiritual lectures, and mindfulness meditation classes. This allows them to immerse themselves in their daily teaching practices, accomplish their work assignments diligently, find meaning in their job, gain confidence, and improve their teaching effectiveness. Academic institutions must offer resources and services to the faculty. Educational institutions must provide research advancement and library service opportunities to access significant research journal databases.

Limitations and Future Avenues

In the absence of worker agility, organization agility is difficult to achieve. Adaptability requires organizations to flexibly organize resources to cope with changing conditions.5 Like every research, there are limitations to this one. The first constraint that may affect the study’s outcome was the participant units and participant size. The participant comprises six units (public sector institutes) in Peshawar, Pakistan, with a total sample size of just 236 employees. The findings may not be generalizable on a global scale. Due to the limited sample size in this study, it is recommended that a larger sample size be used in the future. The data collection was cross-sectional, and follow-up research with different techniques is suggested. Future studies may identify and examine the mediating impact of many other mindset-related factors, including job satisfaction, organization commitment, and trust, in connecting organizational practices and workforce agility.29,125 This would eventually result in academics feeling psychologically empowered and, as a result, improving their agility in the job. This research was conducted at public institutions in Peshawar, Pakistan region. I would suggest conducting a study at private institutes to understand workplace spirituality and workforce agility better. Finally, the proportion of female respondents is insufficient to ensure better results of this study and will be better collected from employees in an equal ratio.

Ethical Standards

The University Review committee (U.R.C.) involving Human Subjects for Iqra National University, Peshawar, Pakistan, has reviewed the proposal stated above and confirmed that all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The participants of this study was the teaching and administration staff of six public institutes in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study to publish this paper. Further, formal approval was obtained from the competent authorities of the organizations that participated in the study. The university research committee approved all the procedures on research involving Human Subjects of Iqra National University Peshawar, Pakistan.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the higher education lecturers and administrative staff that took the time to participate in our research.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Trachsler T, Jong W. Crisis management in times of COVID‐19: game, set or match? J Contingenc Crisis Manage. 2020;28(4):485–486. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12306

2. Varshney D, Varshney NK. Workforce agility and its links to emotional intelligence and workforce performance: a study of small entrepreneurial firms in India. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2020;39(5):35–45. doi:10.1002/joe.22012

3. Ali M, Zhang L, Zhang Z, et al. Can leaders’ humility enhance project management effectiveness? Interactive effect of top management support. Sustainability. 2021;13(17):9526. doi:10.3390/su13179526

4. Jukic I, Calleja-González J, Cos F, et al. Strategies and Solutions for Team Sports Athletes in Isolation Due to COVID-19. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020.

5. Muduli A. High performance work system, HRD climate and organisational performance: an empirical study. Eur J Train Dev. 2015;39:239–257. doi:10.1108/EJTD-02-2014-0022

6. Munteanu I, Newcomer K. Leading and learning through dynamic performance management in government. Public Adm Rev. 2020;80(2):316–325. doi:10.1111/puar.13126

7. Kidd P. Agile Manufacturing: forging New Frontiers. Wokingham, England: Reading, Massachussets, Addison-Wesley. 1994.

8. Sharifi H, Zhang Z. A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations: an introduction. Int J Prod Econ. 1999;62(1–2):7–22. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00217-5

9. Highsmith J. History: the agile manifesto. Retrieved from January 10, 2019; 2021. Available from: http://agilemanifesto.org/history.html.

10. Khattak SR, Saeed I, Rehman SU, Fayaz M. Impact of fear of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nurses in Pakistan. J Loss Trauma. 2020;2020:1–15.

11. Storme M, Suleyman O, Gotlib M, et al. Who is agile? An investigation of the psychological antecedents of workforce agility. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2020;39(6):28–38. doi:10.1002/joe.22055

12. Jena LK, Pradhan S. Workplace spirituality and employee commitment: the role of emotional intelligence and organisational citizenship behaviour in Indian organisations. J Enterpr Inform Manag. 2018;31:380–404. doi:10.1108/JEIM-10-2017-0144

13. Paul M, Jena LK, Sahoo K. Workplace spirituality and workforce agility: a psychological exploration among teaching professionals. J Relig Health. 2020;59(1):135–153. doi:10.1007/s10943-019-00918-3

14. Muduli A, Pandya G. Psychological empowerment and workforce agility. Psychol Stud (Mysore). 2018;63(3):276–285. doi:10.1007/s12646-018-0456-8

15. Ghosh S, Muduli A. Learning agility, culture and outcome: an empirical study. Int J Indian Culture Bus Manage. 2021;23(1):95–110. doi:10.1504/IJICBM.2021.115413

16. Shephard K. Higher Education for sustainability: Seeking Affective Learning Outcomes. International journal of sustainability in Higher Education; 2008.

17. Qadir G, Saeed I, Khan SU. Relationship between motivation and employee performance, organizational goals: moderating role of employee empowerment. J Bus Tour. 2017;3(1):734–747 .

18. Bakar BA. Integrating spirituality in tourism higher education: a study of tourism educators’ perspectives. Tour Manag Perspect. 2020;34:100653. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100653

19. Barkathunnisha AB, Diane L, Price A, et al. Towards a spirituality-based platform in tourism higher education. Curr Issues Tour. 2019;22(17):2140–2156. doi:10.1080/13683500.2018.1424810

20. Ullah R, Saeed I, Khan J, Shahbaz M, Vega-Muñoz A, Salazar-Sepúlveda G. Have you heard that—“GOSSIP”? Gossip spreads rapidly and influences broadly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:13389. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413389

21. Nazir S, Malik S. Workplace spirituality as predictor of workplace attitudes among Pakistani doctors. Sci J Psychol. 2013;2013. doi:10.7237/sjpsych/232

22. Azmy A. The effect of employee engagement and job satisfaction on workforce agility through talent management in public transportation companies. Media Ekonomi Dan Manajemen. 2021;36(2):212–229. doi:10.24856/mem.v36i2.2190

23. Mushtaq R, Shafqat T, Muddassar khan M, et al. Does psychological empowerment mediates the association of workplace spirituality with organizational citizenship behavior and employee burnout? Asia Proc Soc Sci. 2021;7(2):145–149. doi:10.31580/apss.v7i2.1795

24. Jeon KS, Choi BK. Workplace spirituality, organizational commitment and life satisfaction: the moderating role of religious affiliation. J Organ Change Manage. 2021;34:1125–1143. doi:10.1108/JOCM-01-2021-0012

25. Ashmos DP, Duchon D. Spirituality at work: a conceptualization and measure. J Manag Inquiry. 2000;9(2):134–145. doi:10.1177/105649260092008

26. Laabs JJ. Balancing spirituality and work. Personn J. 1995;74(9):60–77.

27. Wu YJ, Chen J-C. Stimulating innovation with an innovative curriculum: a curriculum design for a course on new product development. Int J Manag Educ. 2021;19(3):100561. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100561

28. Kleinberg J. The convergence of social and technological networks. Commun ACM. 2008;51(11):66–72. doi:10.1145/1400214.1400232

29. Paul R, Pradhan S. Achieving student satisfaction and student loyalty in higher education: a focus on service value dimensions. Services Market Quarter. 2019;40(3):245–268. doi:10.1080/15332969.2019.1630177

30. Soliman M, Di Virgilio F, Figueiredo R, et al. The impact of workplace spirituality on lecturers’ attitudes in tourism and hospitality higher education institutions. Tour Manag Perspect. 2021;38:100826. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100826

31. Junior GT, Saltorato P. Workforce agility: a systematic literature review and a research agenda proposal. Innovar. 2021;31:81.

32. Zhang Z, Sharifi H. A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations. Int J Operation Prod Manag. 2000;20:496–513. doi:10.1108/01443570010314818

33. Plonka FE. Developing a lean and agile work force. Human Factors Ergon Manuf Service Industr. 1997;7(1):11–20. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6564(199724)7:1<11::AID-HFM2>3.0.CO;2-J

34. Dyer L, Shafer RA. Dynamic organizations: achieving marketplace and organizational agility with people. 2003.

35. Saeed I, Khan SU, Qadir G, Din JU. How workplace spirituality moderates the relation between job overload and job satisfaction: an empirical evidence. J Administr Bus Stud. 2007;65:83.

36. Ma Y, Bennett D. The relationship between higher education students’ perceived employability, academic engagement and stress among students in China. Educ Train. 2021;63:744–762. doi:10.1108/ET-07-2020-0219

37. Karakas F. Spirituality and performance in organizations: a literature review. J Bus Ethics. 2010;94(1):89–106. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0251-5

38. Jurkiewicz CL, Giacalone RA. A values framework for measuring the impact of workplace spirituality on organizational performance. J Bus Ethics. 2004;49(2):129–142. doi:10.1023/B:BUSI.0000015843.22195.b9

39. Sheep ML. Nurturing the whole person: the ethics of workplace spirituality in a society of organizations. J Bus Ethics. 2006;66(4):357–375. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-0014-5

40. Khan J, Usman M, Saeed I, et al. Does workplace spirituality influence knowledge-sharing behavior and work engagement in work? Trust as a mediator. Manag Sci Lett. 2022;12(1):51–66. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2021.8.001

41. He P, Sun R, Zhao H, Zheng L, Shen C. Linking work-related and non-work-related supervisor–subordinate relationships to knowledge hiding: a psychological safety lens. Asian Bus Manag. 2020;2020:1–22.

42. Marques J, Dhiman SK, Biberman J. Teaching the un-teachable: storytelling and meditation in workplace spirituality courses. J Manag Dev. 2014;33:196–217. doi:10.1108/JMD-10-2011-0106

43. Petchsawang P, Duchon D. Measuring workplace spirituality in an Asian context. Human Resource Dev Int. 2009;12(4):459–468. doi:10.1080/13678860903135912

44. Kinjerski VM, Skrypnek BJ. Defining spirit at work: finding common ground. J Organ Change Manag. 2004;17:26–42. doi:10.1108/09534810410511288

45. Mitroff II, Denton EA. A study of spirituality in the workplace. MIT Sloan Manage Rev. 1999;40(4):83.

46. Giacalone RA, Jurkiewicz CL. Right from wrong: the influence of spirituality on perceptions of unethical business activities. J Bus Ethics. 2003;46(1):85–97. doi:10.1023/A:1024767511458

47. Gerald FC. Spirituality for managers: context and critique. J Organ Change Manage. 1999;12(3):186–199. doi:10.1108/09534819910273793

48. Kanungo RN. The concepts of alienation and involvement revisited. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(1):119. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.1.119

49. Lodahl TM, Kejnar M. The definition and measurement of job involvement. J Appl Psychol. 1965;49(1):24. doi:10.1037/h0021692

50. Kanungo RN. Measurement of job and work involvement. J Appl Psychol. 1982;67(3):341. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.341

51. Joiner TA, Bakalis S. The antecedents of organizational commitment: the case of Australian casual academics. Int J Educ Manag. 2006.

52. Choi Y, Choi JW. A study of job involvement prediction using machine learning technique. Int J Organ Anal. 2020.

53. Jose J, Panchanatham N. Influence of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on job involvement towards organizational effectiveness. Indian J Appl Res. 2014;4(1):280–282. doi:10.15373/2249555X/JAN2014/81

54. Mudrack PE. Job involvement, obsessive‐compulsive personality traits, and workaholic behavioral tendencies. J Organ Change Manage. 2004;17:490–508. doi:10.1108/09534810410554506

55. Cohen A. An examination of the relationships between work commitment and nonwork domains. Human Relations. 1995;48(3):239–263. doi:10.1177/001872679504800302

56. Chen -C-C, Chiu S-F. The mediating role of job involvement in the relationship between job characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. J Soc Psychol. 2009;149(4):474–494. doi:10.3200/SOCP.149.4.474-494

57. Sarros JC, Cooper BK, Santora JC. Leadership vision, organizational culture, and support for innovation in not‐for‐profit and for‐profit organizations. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2011;32:291–309. doi:10.1108/01437731111123933

58. Paullay IM, Alliger GM, Stone-Romero EF. Construct validation of two instruments designed to measure job involvement and work centrality. J Appl Psychol. 1994;79(2):224. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.224

59. Gopinath R, Yadav A, Saurabh S, Swami A. Influence of job satisfaction and job involvement of academicians with special reference to Tamil Nadu Universities. Int J Psychosoc Rehab. 2020;24(3):4296–4306.

60. Van Horn CE, Fichtner AR. An evaluation of state‐subsidized, firm‐based training: the workforce development partnership program. Int J Manpow. 2003;24. doi:10.1108/01437720310464990

61. Takala J, Suwansaranyu U, Phusavat K. A proposed white‐collar workforce performance measurement framework. Industr Manag Data Syst. 2006;106:644–662. doi:10.1108/02635570610666421

62. Papis J. Understanding the workforce: the key to success in a youth hostel in Scotland. Int J Contemp Hospital Manage. 2006;18:593–600. doi:10.1108/09596110610703020

63. Avery K. Mapping the world’s youngest and oldest countries. Visual Capitalist. 2021.

64. Cho E, Tay L. Domain satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between work–family spillover and subjective well-being: a longitudinal study. J Bus Psychol. 2016;31(3):445–457. doi:10.1007/s10869-015-9423-8

65. Wilensky HL. Work, careers and social integration. Int Soc Sci J. 1960;12:543–560.

66. Al Hassan S, Fatima T, Saeed I. A regional study on spillover perspective: analyzing the underlying mechanism of emotional exhaustion between family incivility, thriving and workplace aggression. Glob Region Rev. 2019;4(3):28–36. doi:10.31703/grr.2019(IV-III).04

67. Müller C, Mildenberger T. Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: a systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educ Res Rev. 2021;100394. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100394

68. Humrickhouse E. Flipped classroom pedagogy in an online learning environment: a self-regulated introduction to information literacy threshold concepts. J Acad Librariansh. 2021;47(2):102327. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102327

69. Rashidin MS, Javed S, Liu B. Empirical study on spirituality, employee’s engagement and job satisfaction: evidence from China. Int J Public Admin. 2020;43(12):1042–1054. doi:10.1080/01900692.2019.1665066

70. Kazu H, Demiralp D. Faculty members’ views on the effectiveness of teacher training programs to upskill life-long learning competence. Eur J Educ Res. 2016;63:205–224. doi:10.14689/ejer.2016.63.12

71. Kazemipour F, Mohamad Amin S, Pourseidi B. Relationship between workplace spirituality and organizational citizenship behavior among nurses through mediation of affective organizational commitment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(3):302–310. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01456.x

72. Mahipalan M, Sheena S. Mediating effect of engagement on workplace spirituality–job involvement relationship: a study among generation Y professionals. Asia Pacific J Manag Res Innov. 2018;14(1–2):1–9. doi:10.1177/2319510X18810995

73. Milliman J, Czaplewski AJ, Ferguson J. Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: an exploratory empirical assessment. J Organ Change Manag. 2003;16:426–447. doi:10.1108/09534810310484172

74. Fatima T, Majeed M, Saeed I. Does participative leadership promote innovative work behavior: the moderated mediation model. Bus Econ Rev. 2017;9(4):139–156. doi:10.22547/BER/9.4.7

75. Kolodinsky RW, Giacalone RA, Jurkiewicz CL. Workplace values and outcomes: exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. J Bus Ethics. 2008;81(2):465–480. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9507-0

76. Rabinowitz S, Hall DT. Organizational research on job involvement. Psychol Bull. 1977;84(2):265. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.84.2.265

77. Word J. Engaging work as a calling: examining the link between spirituality and job involvement. J Manag Spiritual Religion. 2012;9(2):147–166. doi:10.1080/14766086.2012.688622

78. Kahn WA. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manage J. 1990;33(4):692–724.

79. Ali M, Zhang L, Shah SJ, et al. Impact of humble leadership on project success: the mediating role of psychological empowerment and innovative work behavior. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2020;41:349–367. doi:10.1108/LODJ-05-2019-0230

80. Brown SP, Leigh TW. A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):358. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.358

81. Van Oyen MP, Gel EG, Hopp WJ. Performance opportunity for workforce agility in collaborative and noncollaborative work systems. Iie Transact. 2001;33(9):761–777. doi:10.1080/07408170108936871

82. Muduli A. Workforce agility: examining the role of organizational practices and psychological empowerment. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2017;36(5):46–56. doi:10.1002/joe.21800

83. Sumukadas N, Sawhney R. Workforce agility through employee involvement. Iie Transact. 2004;36(10):1011–1021. doi:10.1080/07408170490500997

84. Hormozi AM. Agile manufacturing: the next logical step. Benchmarking. 2001;8:132–143. doi:10.1108/14635770110389843

85. Qin R, Nembhard DA, Barnes WL. Workforce flexibility in operations management. Surveys Operation Res Manag Sci. 2015;20(1):19–33. doi:10.1016/j.sorms.2015.04.001

86. Sherehiy B, Karwowski W. The relationship between work organization and workforce agility in small manufacturing enterprises. Int J Ind Ergon. 2014;44(3):466–473. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2014.01.002

87. Natapoera MP, Mangundjaya WL. The effect of employee involvement and work engagement on workforce agility. 2020.

88. He P, Jiang C, Xu Z, et al. Knowledge hiding: current research status and future research directions. Front Psychol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748237

89. Menon S, Suresh M. Enablers of workforce agility in engineering educational institutions. J Appl Res High Educ. 2020. doi:10.1108/JARHE-12-2019-0304

90. Trott DC. Spiritual Well-Being of Workers: An Exploratory Study of Spirituality in the Workplace. The University of Texas at Austin; 1996.

91. Fernando M. Spirituality and leadership. A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. 2011.

92. Fry LW. Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. Leadersh Q. 2003;14(6):693–727. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001

93. Chatterjee A, Naqvi F. Spirituality in organizational life: an empirical study of spirituality and job attitudes. Abhigyan. 2010;28(3):18–30.

94. Hopp WJ, Oyen MP. Agile workforce evaluation: a framework for cross-training and coordination. Iie Transact. 2004;36(10):919–940. doi:10.1080/07408170490487759

95. Goodarzi B, Shakeri K, Ghaniyoun A, et al. Assessment correlation of the organizational agility of human resources with the performance staff of Tehran Emergency Center. J Educ Health Promot. 2018;7. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_109_18

96. Bahrami MA, Kiani MM, Montazeralfaraj R, et al. The mediating role of organizational learning in the relationship of organizational intelligence and organizational agility. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2016;7(3):190–196. doi:10.1016/j.phrp.2016.04.007

97. Aghahosseini EM, Rezaie DH, Nilipour TSA. The impact of human resources agility on crisis management (case study: Blood transfusion organization of Isfahan and other Three accident-prone provinces throughout the country). 2016.

98. Podsakoff N. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;885(879):879–903.

99. Kiess HO, Bloomquist DW. Psychological Research Methods: A Conceptual Approach. Allyn & Bacon; 1985.

100. Sherehiy B. Relationships Between Agility Strategy, Work Organization and Workforce Agility. University of Louisville; 2008.

101. Ashmos DP, Duchon D, McDaniel RR, et al. What a mess! Participation as a simple managerial rule to ‘complexify’organizations. J Manage Stud. 2002;39(2):189–206. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00288

102. Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, et al. Construct validity of the individual work performance questionnaire. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(3):331–337. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000113

103. Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev. 2014;26:106–121.

104. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling.

105. Kline R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guiford; 1998.

106. Shevlin M, Miles JN. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Pers Individ Dif. 1998;25(1):85–90. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00055-5

107. Steiger JH. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;42(5):893–898. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.017

108. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

109. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford publications; 2015.

110. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using Multivariate Statistics. Vol. 5. MA: Pearson Boston; 2007.

111. Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and Validity Assessment. Sage publications; 1979.

112. Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959;56(2):81. doi:10.1037/h0046016

113. Alarcón D, Sánchez JA, De Olavide U. Assessing convergent and discriminant validity in the ADHD-R IV rating scale: user-written commands for Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). In: Spanish STATA Meeting. Universidad Pablo de Olavide; 2015.

114. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Sage CA; 1981.

115. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

116. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

117. Sudiro A, Adi A, Fakhri R. Engaging employees through compensation fairness, job Involvement, organizational commitment: the roles of employee spirituality. Manag Sci Lett. 2021;11(5):1499–1508. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2020.12.023

118. Van der Walt F, Swanepoel H. The relationship between workplace spirituality and job involvement: a South African study. Afri J Bus Econ Res. 2015;10(1):95–116.

119. Utami NM, Sapta I, Verawati Y, Astakoni I. Relationship between workplace spirituality, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J Asian Finance Econom Bus. 2021;8(1):507–517.

120. Bantha T, Nayak U. The relation of workplace spirituality with employees’ innovative work behaviour: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. J Indian Bus Res. 2020. doi:10.1108/JIBR-03-2020-0067

121. Kumar Bandyopadhyay S, Goyal V, Dutta S. Problems and solutions due to mental anxiety of it professionals work at home during COVID-19. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(3–4):604–605.

122. PTA. PTA annual report 2019. PTA official website; 2019. Available from: https://www.pta.gov.pk/en/annual-reports.

123. Gallup Pakistan Survey. Digital learning and online education during COVID-19. 2021.

124. Zada S, Wang Y, Zada M, et al. Effect of mental health problems on academic performance among university students in Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2021;23(3):395–408. doi:10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015903

125. Gruber E, Sarajlic Vukovic I, Musovic M, et al. Personal wellbeing, work ability, satisfaction with life and work in psychiatrists who emigrated from Croatia. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(4):449–462.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.