Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 12

The surgical ward round checklist: improving patient safety and clinical documentation

Authors Krishnamohan N, Maitra I, Shetty VD

Received 2 July 2018

Accepted for publication 14 January 2019

Published 16 September 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 789—794

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S178896

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Nitya Krishnamohan, Ishaan Maitra, Vinutha D Shetty

Department of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Preston, UK

Correspondence: Nitya Krishnamohan

Department of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sharoe Green Lane, Fulwood, Preston PR2 9HT, UK

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The daily surgical ward round (WR) is a complex process. Key aspects of patient assessment can be missed or not be documented in case notes. Safety checklists used outside of medicine help standardize performance and minimize errors. Its implementation has been beneficial in the National Health Service. A structured WR checklist standardizes key aspects of care that need to be addressed on a daily surgical WR. To improve patient safety and documentation, we implemented a surgical WR checklist for daily surgical WRs at our hospital. We describe our experience of its implementation within the general surgical department of a teaching hospital in the UK.

Methods: A retrospective review of case note entries from surgical WRs (including Urology and Vascular surgery) was conducted between April 2015 and January 2016. WR entries of 72 case notes were audited for documentation of six parameters from the surgical WR checklist. A WR checklist label with the parameters was designed for use for each WR entry. A post-checklist implementation audit of 61 case notes was performed between Jan 2016 and August 2016. To assess outcome on patient safety, adverse events relating to these six parameters reported to the local clinical governance team were reviewed pre – and post-checklist implementation.

Results: Overall documentation of the six parameters improved following implementation of the WR checklist (pre-checklist=26% vs post-checklist=79%). Documentation of assessment of fluid balance improved from 8% to 76%. Subsequent audit at 3 months post-checklist implementation maintained improvement with documentation at 72%.

Conclusion: The introduction of the surgical WR checklist has improved documentation of key aspects of patient care. The WR checklist benefits patient safety. It improves communication, documentation and ensures that key issues are not missed at patient assessment on WRs. A crucial factor for successful documentation is engagement by the senior clinicians and nursing staff on its benefits which ensures appropriate use of WR checklist labels occurs as doctors rotate through the surgical placement.

Keywords: ward round, checklist, patient safety, documentation

Introduction

The daily surgical WR is a complex process. A comprehensive list of parameters needs to be considered (Table 1). Once assessment is complete a management plan for the next 24 hours is completed. This is communicated to patient, medical and nursing staff involved in patient care and clearly documented in patient case notes.

|

Table 1 Parameters assessed on surgical WR |

Most often the Consultant or Surgical Registrar leads the surgical WR. The documentation in the case notes is delegated to the most junior member of the team usually the foundation year one doctor. These WRs last several hours, sometimes all day due to the large number of acute in-patients in the hospitals, thus earning the colloquial name of ‘marathon’ WRs. The clinician leading the WR is likely to be interrupted several times, often while assessing a patient. It is inevitable that assessment of one or more variables may not occur. Furthermore, even if assessment is complete, the interpretation of these vital assessments can easily be lost in translation when transcribed to documentation in the case notes.

There is significant variability in the conduct of surgical WRs in the NHS and potential for errors.1 Safety checklists are used in various fields outside of medicine, namely the aviation industry to help standardize performance and minimize human factor-related errors.2,3 These principles have been adapted to its use in health care.2 Checklists aid completion of complex tasks and reduce omissions and variations in practice while strengthening team communication, performance and patient experience.1 The WHO safety checklist is a key example that has improved patient safety and reduced mortality and morbidity in surgery.4,5

The considerative checklist developed by Caldwell et al streamlined the complex process of the WR into a systematic approach describing key aspects of care.3 Pitcher et al identified the deficiencies in general surgical WRs and the benefits of a checklist approach in overcoming this.6 A randomized controlled trial conducted in a simulated environment showed improved standardization, evidence-based management of post-operative complications and quality of WRs.7 These findings and other studies reported in literature demonstrate the benefits of the WR checklist and its impact on patient safety, improving documentation, communication and patient outcomes.3,6,8,9

To improve patient safety and documentation, we implemented a surgical WR checklist for daily surgical WRs at our hospital. We describe our experience of its implementation within the general surgical department of a teaching hospital in the UK.

Methods

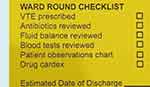

A retrospective review of case notes entries from surgical WRs (including Urology and Vascular surgery) was conducted between April 2015 and January 2016. Recommended standards of WR practice were obtained from joint guidance by the Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Nursing.1 The concept of the surgical WR checklist was derived from the WHO safety checklist.4 The surgical WR checklist summarizes parameters described in Table 1 into key categories. 72 case notes were randomly selected and reviewed pre-checklist implementation. The WR entry for that day was reviewed for documentation of six parameters from the surgical WR checklist (Figure 1). The inclusion of details of a parameter within the WR entry was considered as compliance with documentation of a parameter.

|

Figure 1 Ward round checklist template. |

A yellow label containing key parameters was designed for use for each WR entry (Figure 1). Information regarding the WR checklist was provided to nursing staff and junior doctors via clinical governance meetings and teaching sessions. During the surgical WR, the yellow label was placed within the clinical entry and completed following assessment, review and documentation of each of these parameters.

A post-checklist implementation audit was performed on 61 case notes randomly selected between January 2016 and August 2016. A re-audit was completed 3 months post-checklist implementation.

To assess outcome on patient safety, adverse events relating to these six parameters reported to the local clinical governance team were reviewed between January 2014 and December 2015 prior to implementation of the checklist and between January 2016 and December 2016 post-checklist implementation.

The audit was registered with the Clinical Audit Department at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Data collected was anonymous and non-identifiable. Data was kept confidential in accordance with Trust policy. Patient consent was not required.

Results

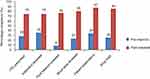

The overall documentation of the six parameters was only 26% in the pre-checklist group and assessment of fluid balance was documented in only 8%.

Following introduction of the WR checklist, overall documentation improved to 79%. The documentation of fluid balance improved to 76% and patient observations to 87%. A subsequent re-audit done 3 months post implementation maintained improvement with overall documentation at 72%. Results are summarized in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2 Documentation of aspects of care pre- and post-checklist implementation. Abbreviation: VTE, venous thromboembolism. |

Adverse events related to the six parameters reported pre- and post-checklist implementation are summarized in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Reported adverse events pre-and post-checklist implementation |

Discussion

The introduction of surgical WR checklist has made a clear improvement in documentation of key aspects of patient assessment and care. Results from the subsequent 3-month re-audit confirm a sustained improvement.

Our findings are supported by recent studies in the surgical setting showing significant improvement in documentation of these key aspects of care with the use of the WR checklist.10,11

While various other types of checklists have been described, using the checklist as a label has its advantages. It prompts the clinician to address those aspects of patient care which might otherwise be missed. In comparison to other studies using the sticker format, our design has several advantages.10,12 They are the same size as patient identification labels and easily fit within a WR entry in the clinical notes. The yellow color also makes it stand out. The labels are concise and easy to follow, encouraging continued use. In this audit, the six parameters selected for the checklist were considered important aspects of care within our practice. These selected parameters were identified as often overlooked or inadequately reviewed during our surgical WRs and deemed requiring further attention. The checklist helps bring focus to these aspects of care. The list of parameters as outlined in Table 1 is not exhaustive and selection of parameters for the checklist can vary according to the requirements of the speciality and serve to highlight parameters commonly missed. The number of parameters selected also needs to consider the size of label used that is conducive with the clinical entry.

The sustained improvement at 3 months indicates that performance can be maintained beyond the initial implementation period. The use of the WR checklist has been established as part of our WR practice since the audit. Banfield et al showed improvement in compliance with the checklist over time and this was maintained even at 2 years, demonstrating the sustainability of such a change in practice.9

The reduction in reported adverse events could in part be indirectly attributed to the effect of the checklist. Most notably, the reduction in prescription errors. The checklist does not serve merely as a ‘tick box’ exercise. Instead, its purpose ensures that important aspects of care are properly addressed on the WR. This contributes towards a culture of improving patient safety. However, bias due to various factors such as efficacy of reporting these events is a limitation with this data. Data whether any cases of venous thromboembolism (VTE) diagnosed was directly due to failure of thromboprophylaxis prescription and implementation was not analyzed in this audit.

In this audit, the quality of the documentation was not assessed. A separate audit would need to be conducted to address this. Further, the improved performance noted could be attributed to the Hawthorne effect as described in another study.5 Assessment of whether improved documentation using the WR checklist impacts patient outcomes such as length of stay or morbidity and mortality would be useful. However, focusing on key aspects of care such as antibiotics, patient observations and VTE prescription as identified in a recent study by Gilliland et al, contributes towards improved patient clinical outcomes.8 Ensuring correct antibiotic use can contribute towards reducing Clostridium difficile rates and prompt identification and management of the ill patient results in lower morbidity.8 Attention to these aspects of care indirectly ensure improved inpatient care and safer and timely discharges.8

Issues with adherence to checklists can be encountered. Reasons include duplication of documentation, time spent completing a checklist without perceived benefit, and poor communication within the team regarding the purpose and timing of checklist use.13 This was overcome by regular teaching and training on its use and benefits at surgical audit meetings and at junior doctor induction. Leadership by senior surgical and nursing staff ensuring its use during the WR encouraged sustained use. Ownership by the senior and junior members of the team of its use promoted continued use. Boland et al identifies these factors as lessons learnt in their study.14 Informal verbal feedback from FY1 doctors was positive. They found it a useful learning tool and a guide to good documentation, reinforcing its use. Qualitative data collected in a study by Ng et al reporting favorable feedback with 89% of respondents mentioning that the checklist should be used regularly reflects this observation.10

In our experience, the sheer volume of workload makes the ability for doctors to carry out thorough documentation suboptimal at times. Sadly, in a court of law, unless documented in the case notes it is considered not done. In an ideal world, all interactions with patients could be video recorded and stored in an inbuilt computer in each patient bed. However, this would be expensive and more importantly raises concerns of privacy and storage. Hence, until newer and more efficient methods of recording WR assessments are developed, the WR checklist labels remain beneficial in improving the efficiency of WR documentation.

We recommend the use of a standardized checklist be incorporated into daily surgical practice in the UK. Senior surgical and nursing colleagues are the key drivers in ensuring its successful implementation and promoting a culture to improve patient safety.

Conclusion

A succinct WR checklist improves documentation and ensures that key issues are not missed at patient assessment on WRs. This contributes towards improved communication between clinical staff and the patient and ultimately patient safety. Additionally, it serves as an educational tool for junior doctors reviewing patients who may be inexperienced in WR practice.

However, designing and issuing a WR checklist is unlikely to have an impact on its own. A successful and sustainable WR assessment and documentation requires a regular programme of focussed education on its benefits to all members of surgical and nursing staff. All junior doctors should be trained in ideal WR documentation and informed of the benefits of the checklist at each induction. A key factor for successful documentation is engagement by the senior clinicians and nursing staff on its benefits which ensures appropriate use of WR checklist labels occurs as doctors rotate through the surgical placement.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing. WRs in Medicine: Principles for Best Practice. London: RCP; 2012.

2. Clay-Williams R, Colligan L. Back to basics: checklists in aviation and healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(7):428–431.

3. Herring R, Caldwell G, Jackson S. Implementation of a considerative checklist to improve productivity and team working on medical WRs. Clin Gov Int J. 2011;16(2):129–136.

4. World Health Organisation. WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. World Health Organisation. Published 2009. Available from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/topics/safe-surgery/checklist/en/. Accessed 19 June 2018.

5. Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):491–499.

6. Pitcher M, Lin JTW, Thompson G, Tayaran A, Chan S. Implementation and evaluation of a checklist to improve patient care on surgical WRs. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(5):356–360.

7. Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Qurashi M, Singh P, Darzi A. Randomized clinical trial of the impact of surgical ward-care checklists on postoperative care in a simulated environment. Br J Surg. 2014;101(13):1666–1673.

8. Gilliland N, Catherwood N, Chen S, Browne P, Wilson J, Burden H. Ward round template: enhancing patient safety on ward rounds. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(2):e000170.

9. Banfield DA, Adamson C, Tomsett A, Povey J, Fordham T, Richards SK. ‘Take Ten’ improving the surgical post-take ward round: a quality improvement project. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(1):e000045.

10. Ng J, Abdelhadi A, Waterland P, et al. Do ward round stickers improve surgical ward round? A quality improvement project in a high-volume general surgery department. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000341.

11. Talia AJ, Drummond J, Muirhead C, Tran P. Using a structured checklist to improve the orthopedic ward round: a prospective cohort study. Orthopedics. 2017;40(4):e663–e667.

12. Alamri Y, Frizelle F, Al-Mahrouqi H, Eglinton T, Roberts R. Surgical ward round checklist: does it improve medical documentation? A clinical review of Christchurch general surgical notes. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(11):878–882.

13. Hale G, McNab D. Developing a ward round checklist to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):

14. Boland X. Implementation of a ward round pro-forma to improve adherence to best practice guidelines. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.