Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 13

The Rural Pharmacy Practice Landscape: Challenges and Motivators

Authors Hays CA , Taylor SM , Glass BD

Received 29 October 2019

Accepted for publication 4 February 2020

Published 2 March 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 227—234

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S236488

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Catherine A Hays,1 Selina M Taylor,1 Beverley D Glass2

1Centre for Rural and Remote Health, James Cook University, Mount Isa, Queensland, Australia; 2Pharmacy, College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Correspondence: Catherine A Hays

Centre for Rural and Remote Health, James Cook University, PO Box 2572, Mount Isa, Queensland 4825 Australia

Tel +61 7 4745 4500

Fax +61 7 4749 5130

Email [email protected]

Background: Health outcome delivery for rural and remote Australian communities is challenged by the maldistribution of the pharmacy workforce. High staff turnover rates, reduced pharmacist numbers, and reliance on temporary staff have placed great strain on both state health services and rural community pharmacies. However, recent changes to the demographic profile of the rural pharmacist including a lower average age and increased time spent in rural practice highlights a more positive future for the delivery of better health outcomes for rural communities. The aim of this study was to investigate the factors that motivate and challenge pharmacists’ choice to practice rurally.

Methods: Rural pharmacists were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews using purposive non-probability sampling. Twelve pharmacists were interviewed with early-, middle- and late-career pharmacists represented. Participants described their experiences of working and living in rural and remote locations. Three themes emerged: workforce, practice environment and social factors, which were examined to determine the underlying challenges and motivators impacting rural and remote pharmacy practice.

Results: Lack of staff presented a workforce challenge, while motivators included potential for expanded scope of practice and working as part of a multidisciplinary team. While social isolation has often been presented as a challenge, an emerging theme highlighted that this may no longer be true, and that notions of “rural and remote communities as socially isolated was a stigma that needed to be stopped”.

Conclusion: This study highlights that despite the challenges rural pharmacists face, there is a shift happening that could deliver better health outcomes for isolated communities. However, for this to gain momentum, it is important to examine both the challenges and motivators of rural pharmacy practice to provide a platform for the development and implementation of appropriate frameworks and programs to better support the rural pharmacy workforce.

Keywords: pharmacy, workforce, rural and remote, health outcomes

Introduction

There has, for many years, been a shortage of pharmacists in rural and remote Australia,1–3 with only 7.8% of Australian pharmacists working outside major cities or inner regional areas, as reported in 2017.4 In addition to being one of the most frequently consulted health professionals in Australia, pharmacists are often the first contact for primary health, especially in rural areas.5,6 Due to limited accessibility of health care in these isolated communities, rural pharmacists play an essential role in rural communities, often providing an expanded scope of pharmacy and health-care services compared to their metropolitan counterparts, including health promotion and education, vaccinations, and disease screening and management.5,7 However, there are currently no specific programs in Australia for rural pharmacy to play an enhanced role.

Despite an increase in pharmacists reported in Australia, analysis of global workforce capacity trends from 2006 to 2012, the authors mentioned that an increase in workforce density does not necessarily describe distribution.8 This has implications for accessibility, as health-care professionals generally tend to gravitate to urban rather than rural areas. It is therefore questioned whether the predicted over supply of pharmacists in Australia by 2025, will address the current maldistribution of pharmacists.1–4

A demographic profile of a rural and remote pharmacist in Australia was identified by Smith et al in 2013, which places these pharmacists as 15 years older than the national average, over 50% from a rural background with an even gender distribution.1 Rural pharmacists have expressed satisfaction with their role, giving reasons such as a rewarding and close relationships with their patients, lifestyle, business opportunity and financial incentives to practice rurally.9 On the negative side, balancing workload with lifestyle, and family commitments, professional isolation and some financial constraints have been put forward as being challenging.9,10

Taylor and Glass recently published on the influence of curriculum and clinical placements on pharmacists’ choice to practice rurally, where they found that rural placements had a significant impact, while the curriculum had little effect.11 There also appears to have been a shift in the demographic profile of the rural pharmacist from 2013, with 65% being female, which more accurately reflects the current gender distribution of pharmacists in Australia.11 This together with the fact that over 60% of the respondents were in the age group 25–45 years, having spent over 6 years in rural practice, signals a more positive future for the delivery of better health outcomes for rural communities.11 This is aligned with previous findings that rural lifestyle influences the decision to practice rurally. However in contrast to the findings by Smith et al in 2013, a rural origin was not found to be a significant determinant of choosing to practice rurally.1,11 The aim of this study was to investigate factors that motivate and challenge pharmacists’ choice to practice in rural and remote Australia.

Methods

A qualitative method of semi-structured interviews was chosen due to the complexity of the research area, which is largely unexplored.12 Following a review of the literature, semi-structured interview questions were designed and developed to ensure alignment with the research aim, while allowing in-depth discussion. The interview questions were piloted with two pharmacists and minor changes to language were made.

Purposive non-probability sampling of pharmacists from membership lists of the following rural pharmacist networks was undertaken: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, Society for Hospital Pharmacists, Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health, Rural Pharmacists Support Network and James Cook University School of Pharmacy Alumni.

Pharmacists were invited to participate via multiple methods including email, newsletter distribution and Facebook posts. Semi-structured interviews (see Table 1) were conducted in September 2018 with 12 participants via telephone. Interviews took, on average, 30 mins to complete until a saturation point with the emerging themes was achieved. These interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

|

Table 1 Semi-Structured Interview Questions |

Data Analysis

The methodology for this project aligns with constructivist grounded theory tradition within qualitative research.13 The aim was to achieve a detailed understanding of the varying perspectives presented in interviews, and to position them within a continuum of broader underlying values and experiences, both personal and professional. This approach to data collection was progressive, in that knowledge and themes generated in the first interviews were considered, compared, and built upon throughout subsequent interviews.

Interview transcripts were thematically analyzed using NVivo (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018, http://www.qsrinternational.com/product) using line by line analysis with themes coded into common categories, independently validated by a second researcher and a third researcher dealt with any inconsistencies to ensure coherence and analysis triangulation.

Ethical Considerations

James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval (H7228). Participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. All interview transcripts were de-identified, including the removal of any potentially identifying words removed, to ensure participant confidentiality.

Results

Participants’ Profile

Table 2 describes the demographic characteristics of the 12 rural pharmacists (aged 21–65; 58% female) who participated in the study. While the largest proportion of interviewees (n=5) were in the early stages of their career (≤10 years), middle and late career pharmacists were also represented. Half of the participants (n=6) had been working in remote and very remote areas for over 15 years, while 5 of the participants originated from a rural or remote region of Australia. Remoteness was measured using the Modified Monash Model, used by Australian Government departments to classify towns and regions as metropolitan, regional, rural or remote according to population size and geographical remoteness.14 Areas assigned to categories MM3-7 can be classified as rural or remote.14

|

Table 2 Demographic Profile of Participants |

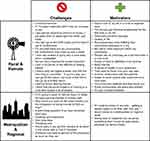

Figure 1 represents the analysis of the semi-structured interviews, which resulted in the emergence of three themes from the data: rural and remote pharmacy workforce, practice environment, and social factors. Locations and workplace names have been de-identified. Figure 2 provides additional verbatim quotes from participants, characterized as challenges and motivators for rural practice. These were also categorized according to location (rural and remote or metropolitan and regional).

|

Figure 1 Themes and sub-themes identified. |

|

Figure 2 Challenges and motivators: verbatim quotes from participants. |

Pharmacy Workforce

A variety of factors that contribute to the stability of the rural and remote pharmacy workforce were discussed, including a lack of staff, length of time to fill vacant positions, high turnover of staff, and difficulty finding both permanent staff and locums.

I went back to Sydney, went into the (pharmacy) guild, said, I would like a position somewhere on the coast, near the beach, and they said, (rural location) …. They were looking for a pharmacist for five years.

We struggled to have permanent pharmacists … it wasn’t until August last year we got our first full-time permanent, and she’s still here.

Fear and unfamiliarity of rural and remote locations were identified by five participants to be a barrier for choosing to relocate rurally for work. Having a rural background was described as having a positive influence on the choice to go rural.

You don’t come and work in a rural town if you’re not familiar with rural areas and you’ve lived in the city all your life.

Having grown up rurally and then living in the city …. Definitely ready to go back to a rural setting.

Financial incentives for rural and remote practice were discussed frequently, with seven of the participants stating that they received better pay for working in a rural or remote location, compared to a metropolitan or regional area. Better job security and permanent fulltime employment were also stated to be motivating factors in the choice to work rurally.

I suppose the reason I have stayed in rural pharmacy … money would be the primary motivating factor.

When I was in (metropolitan city) I could not get full-time work … so security, a good remuneration package and paid holidays are good.

In contrast however, one of the pharmacists who had been in the workforce for over 20 years stated that they earned less now than they did 20 years ago, despite their experience and range of skills.

Working rurally was also associated with better career satisfaction, with participants reporting that they felt more appreciated and challenged compared to metropolitan areas.

I definitely find rural pharmacy more fulfilling than I do community pharmacy in a city … my role is more important and diverse, and people rely on pharmacy as a service more in a rural town.

Lifestyle factors included working hours, work-life balance, and reduced travel/commute time. However, one participant reported found that they were working longer hours, which impacted their lifestyle.

In these rural areas … You are working generally longer weeks because quite often you are the sole pharmacist.

Practice Environment

Participants in management positions highlighted some of the major differences between a metropolitan and rural or remote pharmacy, particularly the need for resilience, good stock control, and understanding the reduced access to services and logistical issues that affect rural and remote areas.

So many of the things that you do on a day-to-day basis in very remote areas, it’s different, it’s more difficult because you just don’t have access to the same resources as you do closer to the coast. You have to be on top of things … Organized and pay more attention to stock control due to potential delays in delivery.

Differences in health issues between metropolitan/regional and rural or remote regions were also described, such as the mental health crises following loss of livestock and property due to long-term drought or other natural disasters.

I think that there are public health issues to be more aware of … communities that have been really struggling for decades with drought and all sorts of other natural disasters. Some of those things are very challenging and very confronting.

An expanded scope of practice for pharmacists in rural and remote areas was viewed positively by participants, as it allowed them to gain a wider range of skills and experience while providing essential services to their communities. In very remote areas without a full-time doctor, pharmacy was viewed as filling an important health service gap.

We’ve got a doctor that comes out for two three-hour sessions a week … (patients) go to the pharmacy and hope that there’s something that you can do, so your triage skills have to be a lot better in rural pharmacy I think.

It’s just really quite bizarre where rural pharmacy has been; it’s taken a long time to realize that rural pharmacy has a role that’s distinct from other pharmacy.

Working as part of the multidisciplinary health team and being more deeply involved with the healthcare system were also viewed positively.

It was brilliant, because I think the thing that a lot of people don’t realize about very rural areas like that is the potential to really function as part of the whole multidisciplinary healthcare team … professionally it was very satisfying.

A difference in patient relationships was an important factor that positively affected participants’ choice to remain in a rural or remote location, including familiarity with patients and feeling trusted. Furthermore, patient contact experiences in metropolitan areas were often viewed negatively.

One of my patients came in for a prescription for antidepressants and she was so ashamed and so embarrassed … but she knew she could trust me enough to have this discussion and not judge her.

Participants also described that professional isolation was an issue, as they could sometimes be working alone as a sole pharmacist. Difficulties in attending conferences and a lack of professional development opportunities were also discussed.

Social Factors

One of the most frequently discussed positive social factors was a stronger feeling of community, familiarity with community members, and friendships and relationships made within remote areas. A sense of camaraderie was also felt with others that had relocated for work, and communities were admired for their resilience.

I think you either are used to it or you’re not, that familiarity that there is no anonymity, like it takes me half an hour to go and buy milk, because you bump into everybody, which is great. But some people like it and some people don’t. I do. I love it.

People are really nice; I’ve met some really great people up here … So everyone’s away from home, everyone’s up here for work, so everyone’s trying to make the most of an opportunity, while you’re living in such a great part of the world.

Some of these more rural communities are absolutely brilliant. (Very remote community) was just fabulous, absolutely fabulous community spirit, wonderful people, despite the drought, the resilience of the people is quite, quite amazing.

Despite these positive views of rural and remote communities, personal and social isolation were common themes, discussed by several participants. Difficulties making new friends and having to leave friends and family were perceived as negative consequences of choosing to live and work rurally. Additionally, the cost, distance, and frequency of plane travel to rural and remote areas exacerbated this issue, making it difficult to leave town.

In a small town that can actually be lonelier than living in a really big place. danger can be limitation to the provision of support services and there is lack of access to public and affordable transport e.g. flights which when they are available might be unreliable and costly.

In particular, the difficulties of finding a long-term partner in rural and remote areas were highlighted.

These populations are very mobile, so you could meet someone and they could be gone in three months or six months … even if they’re happy … creates problems with sustaining relationships.

However, two participants had different experiences, with one even saying that the notion of rural and remote communities being socially isolated was a “stigma” that needed to be stopped:

I met somebody, had a family, all of that. Got a lot of friends in this area. Decided it was pretty much one of the perfect areas on this earth and stayed here.

I think that’s one area that we can work on … to break down that stigma, because I can tell you right now that in (rural town), I don’t think that anyone is feeling socially isolated.

Discussion

The majority of Australia’s health workforce reside in metropolitan or regional cities, while rural and remote areas are often chronically understaffed.10,15,16 This maldistribution has been well documented in the past, in the fields of medicine, nursing, and allied health disciplines as well as pharmacy.4,16-19 High rates of turnover, a lack of staff, and reliance on the recruitment of short-term locums not only has a high financial cost, but may lead to safety risks to staff and patients and a lower quality of health-care provision.5,20-23 In pharmacy, this may include limited medication management services and reduced access to services.15 Despite programs and incentives being in place to improve the state of the pharmacy health workforce throughout rural and remote Australia, such as the Sixth Community Pharmacy Agreement Rural Support Programs (6CPA)24 and rural placement opportunities25 for undergraduate pharmacy students, the pharmacy workforce maldistribution persists.4

Pharmacy Workforce

In addition to high turnover rates, health professionals also tend to have shorter stays in rural areas.22 Rural and remote health professionals tend to have a higher workload than their regional and metropolitan counterparts, which can be exacerbated by short staffing, difficulty accessing locums, a wider range of duties, and being a sole pharmacist.1,9,10,19,26 Despite this, rural and remote pharmacists have often reported to have a better lifestyle or quality of life than their metropolitan counterparts, and job satisfaction is generally high.1,10,18,25,26 Additionally, 50% of participants in this study have worked rurally for over 15 years, demonstrating a long-term commitment to rural pharmacy.

Practice Environment

Lack of access to professional development opportunities and conferences are not uncommon to the rural and remote pharmacy workforce.9,10,17,19,25 Geographical distance, cost of travel and accommodation, and inability to replace pharmacy staff on leave are factors that may interfere with the ability to attend educational training and conferences.18 However, pharmacists generally view rural practice positively, particularly enjoying the challenges of an expanded scope of practice and working as part of a multidisciplinary team.1,10,15 Rapport and familiarity with patients, and feeling valued and respected are also consistently cited as drivers for staying in rural and remote practice.1,10,18,25,26

Social Factors

Perhaps the most important factors influencing pharmacists’ decision to live and work rurally are those related to perceptions of personal and social isolation. Experiences and perceptions regarding distance from family and friends, loneliness, and concerns regarding making new friends are often reported in the literature.1,18,25,26 However, family can also be a motivating factor, as some may choose to relocate to meet their partner’s needs or move their family to a rural area. Interestingly, the lack employment for partners and availability or quality of rural and remote schooling, which have been previously described were not discussed by participants in this study.1,9,10 Feelings of belongingness and “sense of community” are also important to rural and remote pharmacists, and may increase retention.1,16,19,26

Having a rural background is known to be associated with willingness to live and work rurally.1,10,26,27 Of the twelve participants of this study, seven were of rural origin, and five of these had spent over 15 years working in rural pharmacy, which supports this association.

Conclusion

Pharmacists are well-recognized health-care providers working in diverse and complex rural and remote locations around Australia. As the chronic disease burden rises, the need to look closely at the current motivators and challenges is pertinent to addressing poor health outcomes from the perspective of access to quality medicines and pharmaceutical care. Studies from 10 years ago describe some similar enablers and barriers to rural pharmacy practice, which indicates that many of the issues that rural pharmacists face are ongoing. This highlights the importance of considering this data closely, and the notion that change is needed to support the rural pharmacy workforce and consequently improve health outcomes for rural and remote Australians. The findings of this study can be applied to future pharmacy workforce recruitment and retention strategies in rural and remote locations in Australia.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the rural and remote pharmacists who generously gave up their time to participate in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Smith JD, White C, Roufeil L, et al. A national study into the rural and remote pharmacist workforce. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(2):2214.

2. Health Workforce Australia. Australia’s Health Workforce Series - Pharmacists in Focus. 2014. Available from: http://iaha.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/HWA_Australia-Health-Workforce-Series_Pharmacists-in-focus_vF_LR.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2019.

3. Gupte J. One workforce model doesn’t fit all. Aust J Pharm. 2010;91(1084):8.

4. Department of Health. Pharmacists 2017 Factsheet. 2019. Availabile from: https://hwd.health.gov.au/webapi/customer/documents/factsheets/2017/Pharmacists.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2019.

5. Wibowo Y, Berbatis C, Joyce A, Sunderland V. Analysis of enhanced pharmacy services in rural community pharmacies in Western Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1400.

6. Sunderland B, Burrows S, Joyce A, McManus A, Maycock B. Rural pharmacy not delivering on its health promotion potential. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14(3):116–119. doi:10.1111/ajr.2006.14.issue-3

7. Saini B, Filipovska J, Bosnic‐Anticevich S, Taylor S, Krass I, Armour C. An evaluation of a community pharmacy‐based rural asthma management service. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(2):100–108. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00975.x

8. Bates I, John C, Seegobin P, Bruno A. An analysis of the global pharmacy workforce capacity trends from 2006 to 2012. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):3. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0267-y

9. Smith JD, White C, Luetsch K, Roufiel L, Battye K, Pont L. What does the rural pharmacist workforce look like? Australian Pharmacist. 2011;30(12):1037–1039.

10. Harding A, Whitehead P, Aslani P, Chen T. Factors affecting the recruitment and retention of pharmacists to practice sites in rural and remote areas of New South Wales: a qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14(5):214–218. doi:10.1111/ajr.2006.14.issue-5

11. Taylor SM, Lindsay D, Glass BD. Rural pharmacy workforce: influence of curriculum and clinical placement on pharmacists’ choice of rural practice. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(2):132–138. doi:10.1111/ajr.2019.27.issue-2

12. Mills J, Birks M. Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide. London: Sage; 2014.

13. Birks M, Mills J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide.

14. Department of Health. Modified Monash Model. 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/modified-monash-model#what-is-the-modified-monash-model.

15. Tan ACW, Emmerton LM, Hattingh HL. Issues with medication supply and management in a rural community in Queensland: rural medication supply and management. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(3):138–143. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2012.01269.x

16. Campbell N, Eley DS, McAllister L. How do allied health professionals construe the role of the remote workforce? New insight into their recruitment and retention. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167256.

17. Cosgrave C, Hussain R, Maple M. Retention challenge facing Australia’s rural community mental health services: service managers’ perspectives. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23(5):272–276. doi:10.1111/ajr.2015.23.issue-5

18. Onnis LaL PJ. Health professionals working in remote Australia: a review of the literature. Asia Pac J Human Res. 2016;54(1):32–56. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12067

19. Cosgrave C, Maple M, Hussain R. An explanation of turnover intention among early-career nursing and allied health professionals working in rural and remote Australia - findings from a grounded theory study. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(3):4511. doi:10.22605/RRH4511

20. Russell DJ, Zhao Y, Guthridge S, et al. Patterns of resident health workforce turnover and retention in remote communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, 2013–2015. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12960-017-0229-9

21. Bragg S, Bonner A. Losing the rural nursing workforce: lessons learnt from resigning nurses. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23(6):366–370. doi:10.1111/ajr.2015.23.issue-6

22. Chisholm M, Russell D, Humphreys J. Measuring rural allied health workforce turnover and retention: what are the patterns, determinants and costs? Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(2):81–88. doi:10.1111/ajr.2011.19.issue-2

23. Zhao Y, Russell DJ, Guthridge S, et al. Cost impact of high staff turnover on primary care in remote Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2018;43(6):689–695.

24. Department of Health. 6th Community Pharmacy Agreement. 2015. Available from: http://6cpa.com.au/.

25. Kirschbaum M, Khalil H, Taylor S, Page AT. Pharmacy students’ rural career intentions: perspectives on rural background and placements. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8:615–621.

26. Khalil H, Leversha A. Rural pharmacy workforce challenges: a qualitative study. Australian Pharmacist. 2010;29(3):256–260.

27. Fleming CA, Spark MJ. Factors influencing the selection of rural practice locations for early career pharmacists in Victoria: rural pharmacy practice: demographics. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(6):290–297. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01234.x

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.