Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 13

The relationship between childhood trauma and adult psychosis in a UK Early Intervention Service: results of a retrospective case note study

Authors Reeder FD, Husain N, Rhouma A, Haddad PM, Munshi T, Naeem F, Khachatryan D, Chaudhry IB

Received 19 October 2015

Accepted for publication 5 May 2016

Published 8 February 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 269—273

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S98605

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Francesca D Reeder,1 Nusrat Husain,2 Abdul Rhouma,3 Peter M Haddad,2 Tariq Munshi,4 Farooq Naeem,4 Davit Khachatryan,4 Imran B Chaudhry2

1School of Medicine, 2Neurosciences and Psychiatry Unit, University of Manchester, Manchester, 3Early Intervention Service, Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust, Preston, UK; 4Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Aim: There is evidence that childhood trauma is a risk factor for the development of psychosis and it is recommended that childhood trauma is inquired about in all patients presenting with psychosis. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of childhood trauma in patients in the UK Early Intervention Service based on a case note review.

Methods: This is a retrospective case note study of 296 patients in an UK Early Intervention Service. Trauma history obtained on service entry was reviewed and trauma experienced categorized. Results were analyzed using crosstab and frequency analysis.

Results: The mean age of the sample was 24 years, 70% were male, 66% were White, and 23% Asian (ethnicity not documented in 11% of the sample). Approximately 60% of patients reported childhood trauma, 21% reported no childhood trauma, and data were not recorded for the remaining 19%. Among those reporting trauma, the prevalence of most frequently reported traumas were: severe or repeated disruption (21%), parental mental illness (19%), bullying (18%), absence of a parent (13%), and ‘other’ trauma (24%) – the majority of which were victimization events. Sixty-six percent of those reporting trauma had experienced multiple forms of trauma.

Conclusion: A high prevalence of childhood trauma (particularly trauma related to the home environment or family unit) was reported. This is consistent with other studies reporting on trauma and psychosis. The main weakness of the study is a lack of a control group reporting experience of childhood trauma in those without psychosis. Guidelines recommend that all patients with psychosis are asked about childhood trauma; but in 19% of our sample there was no documentation that this had been done indicating the need for improvement in assessment.

Keywords: childhood trauma, psychosis, abuse, bullying, family

Introduction

An abundance of literature documents an association between childhood trauma and the later development of a broad list of physical and mental illnesses including; eating disorders, substance abuse, phobias, personality disorder, irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disorders.1–5 More recently, evidence has accumulated to link the childhood adversity to the development of adult psychosis. A meta-analysis showed a significant association between adversity and psychosis across three research designs that were systematically reviewed (prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and case-control studies) with an overall effect of odds ratio 2.78 (95% confidence interval 2.34–3.31).6 A causal link between childhood trauma and psychosis has been suggested and it is postulated that this is mediated via a neuropathological stress response that involves dysregulation of the hypothalamic pituitary axis, disruption of dopamine and neurotransmitter systems, and hippocampal damage.7

The existing evidence highlights the need for a routine, systematic trauma history to be taken from every patient presenting with significant mental health problems in order for the most effective care to be provided.8 This includes the provision of evidence based psychosocial therapies such as those recommended in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence schizophrenia guidelines.9 Failure to assess whether past trauma can impact on current problems means a failure to fully determine the potential benefits of referral to therapy, thus hindering a patient’s recovery from psychosis. Furthermore, a patient bias to underreport experiences of trauma has been documented, further obviating the need for direct questioning from mental health care professionals.10,11

In this study we aimed to determine the proportion of patients in an early intervention service with a history of trauma and to describe the types of trauma most commonly experienced.

Methodology

The data for this paper were derived from a retrospective case note audit, and an evaluation of an UK Early Intervention Service. The audit aimed to assess service accessibility, quality of assessments, and to gain a better understanding of the characteristics of patients within the service in order to assist future service development. The study was approved by the Lancashire Care Research and Development department as a retrospective case note audit. All the data was anonymized and patients were not contacted at anytime for any information, hence consent was not obtained.

Setting

The Early Intervention Service is located in the north of England and criteria for entry include; aged between 16 and 35 years and within 3 years of commencing treatment for a psychotic disorder. Data were collected from all patients currently in the service at the time (n=296). Every patient entering the service was assessed by a member of the Early Intervention team.

Assessment

The assessing health care professional gathered a range of data on the patients’ history and mental state in a systematic fashion and recorded this on a Health and Social Needs Assessment proforma, which also acted as a prompt and guide during the assessment. Information was collected on fifteen categories of childhood trauma including physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, sexual abuse, witnessing domestic abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual), death of one or both parents, absence of one or both parents, parental mental illness, family suicide, forced marriage, bullying, and severe or repeated disruption. Categories were not exclusive ie, a patient could be recorded as experiencing one of the categories of trauma, or any number of them. The parents included biological and non-biological parents, and legal or non-legal guardians. Severe or repeated disruption included frequent, repeated, or traumatic house or school moves, including suspension or expulsion from a number of schools, repeated custodial sentences, placement in state or foster care, and separation from parents or siblings. An ‘other’ category allowed qualitative information to be collected and documentation of trauma not fitting into the other fifteen categories. Results were analyzed using crosstab and frequency analysis to show trauma correlates and to compare different groups of patients. In conducting the audit we recorded in what proportion of cases the Health and Social Needs Assessment proforma had not been fully completed.

Results

Patient demographics

The majority of patients within the service were male (70%, n=207). The most predominant ethnicity was White (66%, n=195), followed by Asian (23%, n=68), and mixed race (0.7%, n=2). Ethnicity was not documented in 11% of patients (n=32). The mean age of patients was 24 years.

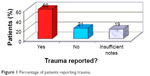

Of the 296 patients studied, 178 (60%) had experienced some sort of childhood trauma (Figure 1). Fifty-five patients (19%) had insufficiently completed Health and Social Needs Assessments documented to determine whether or not childhood trauma had occurred, and 63 patients (21%) had no evidence of childhood trauma.

| Figure 1 Percentage of patients reporting trauma. |

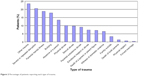

As shown in Figure 2, the most common types of trauma reported were: 1) other trauma (24%); 2) severe or repeated disruption (21%); 3) parental mental illness (19%); 4) bullying (18%); and 5) absence of a parent (13%). It is interesting to note that three out of five of the most common traumas relate to factors within the family unit.

| Figure 2 Percentage of patients reporting each type of trauma. |

Qualitative analysis of the ‘other trauma’ category revealed victimization events to be the most common, with isolated sexual assaults making up the majority (29%). Traumatic parental divorce was second to this with 17% describing this as contributing to their current problems. Interestingly, 22% of patients in this category stated they had a ‘difficult relationship’ with one or both parents.

Multiple trauma

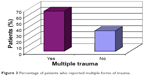

Of the 178 patients who reported childhood trauma, 118 (66%) had experienced multiple forms. This is in keeping with the finding that ‘severe or repeated disruption’ was the second most common trauma type (Figure 3).

| Figure 3 Percentage of patients who reported multiple forms of trauma. |

Discussion

Our finding that the majority (60%) of patients presenting to the Early Intervention Service had experienced some form of childhood trauma is consistent with other studies that have reported a high prevalence of childhood trauma in those with adult psychosis.5–7 We must also take into account previous evidence that patients are biased to underreport trauma. This, and the high proportion of insufficient notes, might have resulted in misleadingly lower rates of trauma.10,11 Based on extrapolation from our data, another 32 patients in this sample could reasonably be expected to have experienced unreported trauma.

The number of patients with incomplete notes is concerning – we cannot provide sufficient help for patients coping with trauma sequelae if we are not aware of the trauma in the first place. The ideology behind the most commonly offered psychological therapies in Early Intervention Services – cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) – is to understand how one’s past experiences affect current thoughts and behaviors and to try and break unhelpful cycles. Failure to document or explore trauma prevents us fully assessing whether a patient is likely to benefit from therapy and potentially hinders referral rates and ultimately, the patient’s recovery. As suggested by Read et al,8 by failing to provide timely psychological intervention to patients we could be ‘unnecessarily exposing them to the side-effects of neuroleptic medication’. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication are a particular concern in first episode psychosis patients.12

Possible reasons for failing to explore trauma may be suboptimal staff training, resulting in a lack of confidence to approach the subject with patients, fear of jeopardizing staff-patient relationship, and uncertainty of what to do should a patient respond positively when asked about trauma.

Multiple trauma

Lardinois et al13 proposed that those who have experienced childhood trauma develop an acquired vulnerability to psychosis through previous trauma exposure, creating increased emotional reactivity to daily stressors. Essentially, it appears that the patient is able to cope with their trauma but they are less able to cope with daily stressors in addition to their trauma and it is this that ultimately leads to their deterioration in mental health.13 Neria et al14 also found an increased rate of psychosis in those exposed to repeated or ongoing trauma.

The above knowledge may inform the type of interventions offered to patients. Although evidence suggests that generally patients do not become distressed when asked about trauma, there are also patients who are not ready to or able to come to terms with or discuss their trauma.15 For individuals who decline CBT on this basis, an appropriate alternative may be offered which focuses on helping patients cope with daily stressors. Safeguarding issues are also raised here as those children exposed to trauma appear more likely to be exposed again. Similarly, those who have already been exposed to multiple trauma have obviously not been safeguarded appropriately.

The importance of factors within the family unit

In this study, 80% of the most common traumas reported were related to factors within the family home (severe or repeated disruption, parental mental illness, absence of a parent, and traumatic parental divorce). This echoes Janssen et al’s15 finding that parental rearing styles predicted the onset of psychosis and suggests factors within the family unit may have more clinical significance than previously thought. In particular, they appear to have more relevance than victimization events, such as sexual abuse, which have historically been the mainstay of research into trauma and psychosis.15,16 Increased mindfulness of this inference and efforts to strengthen family relationships may serve as protective factors in the development or relapse of psychosis. Family therapy may be especially beneficial and these findings warrant its increased role in the management of psychosis.

Limitations

This is a retrospective study. We also did not include a control group to establish the prevalence of trauma in people who never develop psychosis or display early signs of psychosis. The definition of trauma is open to researcher bias for some categories of trauma. ‘Severe or repeated disruption’ is a good example of this. The design of this study assumes only association between the childhood trauma and subsequent psychotic illness; it does not establish causality and therefore, other confounding factors have not been accounted for. We are also unable to rule out that more recent life events were causal factors in the development of patients’ psychosis. Furthermore, due to an apparent lack of direct questioning from health care professionals within the service or shortage of appropriately documented history taking, it is likely that a substantial amount of trauma has not been included in our results.

Conclusion

We found a high prevalence of childhood trauma in patients either with established psychosis or displaying signs of early psychosis. This is consistent with other research that has linked childhood trauma to psychosis. Irrespective of this, good psychiatric practice requires a comprehensive understanding of an individual’s problems. As such, mental health care professionals should ensure a full trauma history is taken from all patients presenting with psychosis in order that the most optimal mental health care can be delivered. This high prevalence of trauma reported within the family home raises the possibility that patients may benefit from family therapy or trauma focused CBT in the management of psychosis.

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to the staff at The Hub Early Intervention Service Blackburn, in particular, Lynda Dempsey, Kath Wilkinson, and Sharon Ingham for their help and support in this project.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–186. | ||

Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. | ||

Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1453–1460. | ||

Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(6):625–639. | ||

Larkin W, Read J. Childhood trauma and psychosis: evidence, pathways, and implications. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54(4):287–293. | ||

Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):661–671. | ||

Ruby E, Polito S, McMahon K, Gorovitz M, Corcoran C, Malaspina D. Pathways associating childhood trauma to the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Front Psychol Behav Sci. 2014;3(1):1–17. | ||

Read J, Hammersley P, Rudegeair T. Why, when and how to ask about childhood abuse. AdvPsychiatr Treat. 2007;13(2):101–110. | ||

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management; 2014 [updated March, 2014]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/About-this-guideline#copyright. Accessed July 22, 2016. | ||

Darves-Bornoz JM, Lempérière T, Degiovanni A, Gaillard P. Sexual victimization in women with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(2):78–84. | ||

Dill DL, Chu JA, Grob MC, Eisen SV. The reliability of abuse history reports: a comparison of two inquiry formats. Compr Psychiat. 1991;32(2):166–169. | ||

Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1350–1363. | ||

Lardinois M, Lataster T, Mengelers R, Van Os J, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and increased stress sensitivity in psychosis. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2011;123(1):28–35. | ||

Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Sievers S, Lavelle J, Fochtmann LJ. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: findings from a first-admission cohort. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):246–251. | ||

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Hanssen M, et al. Are apparent associations between parental representations and psychosis risk mediated by early trauma? Acta Psychiat Scand. 2005;112(5):372–375. | ||

Freeman D, Fowler D. Routes to psychotic symptoms: trauma, anxiety and psychosis-like experiences. Psychiat Res. 2009;169(2):107–112. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.