Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 12

The relation of serum prolactin levels and Toxoplasma infection in humans

Authors Mohammadpour A, Keshavarz H, Mohebali M, Salimi M, Teimouri A , Shojaee S

Received 28 September 2018

Accepted for publication 23 November 2018

Published 20 December 2018 Volume 2019:12 Pages 7—12

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S188525

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

A Mohammadpour,1 H Keshavarz,1 M Mohebali,1 M Salimi,1 A Teimouri,1,2 S Shojaee1

1Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 2Students Scientific Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan parasite distributed worldwide. Although the infection is benign in immunocompetent individuals, it is life threatening and complicated in immunocompromised patients and fetuses of pregnant women who received their first exposure to T. gondii during the pregnancy. Prolactin (PRL) is a hormone that is secreted by the pituitary gland, and it is confirmed that it plays a role in the immune system. The present study was carried out to assess the possible relation between serum PRL levels and Toxoplasma infection frequency in human.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, 343 serum samples (240 from women and 103 from men) were collected from individuals who were referred for PRL checking in laboratories of Karaj, Iran. Blood samples were collected, and sera were separated and analyzed for the detection of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody by ELISA method. The levels of PRL were measured by Roche Elecsys 2010 analyzer, electrochemiluminescence technology.

Results: Of 343 sera, 110 samples (32%) consisting of samples from 42 men and 68 women had anti-T. gondii IgG antibody. The prevalence of T. gondii infection in women with high PRL levels was lower than that in the comparison group with normal levels of PRL and the relationship between these two parameters was statistically significant (P=0.016). In women with hyperprolactinemia, by increasing of PRL levels, the prevalence of T. gondii infection was reduced.

Conclusion: The results of the current study confirmed the previous studies based on immunoregulatory role of PRL and indicated that high levels of PRL could be related to Toxoplasma seronegativity in women.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, IgG antibody, prolactin, ECL technology, hypoprolactinemia, cytokines, hyperprolactinemia, dopamine

Background

Toxoplasma gondii, the protozoan parasite distributed worldwide, is common among humans and a broad range of warm-blooded animals.1 The main routes of human infection are by the consumption of raw or undercooked meat containing tissue cysts and ingestion of oocysts via other food products, water, or vegetables.2 Congenital infection can occur by vertical transmission of rapidly dividing T. gondii tachyzoites during pregnancy.3 Prenatal infection leads to an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, chorioretinitis, or serious neurodevelopmental disorders such as hydrocephaly and microcephaly.3 Although T. gondii infection is benign in immunocompetent individuals, it is life threatening in congenital form and in immunocompromised patients due to reactivation of the infection.4 Therefore, accurate diagnosis of acute maternal toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients and pregnant women is critical.5 Prevalence of toxoplasmosis varies widely among different regions of the globe and depends on meat cooking habits, socioeconomic status, and geographical conditions such as temperature and humidity.6,7 In Iran, seroprevalence ranged from 14.8% to 66% with typically increasing level according to age, and the overall seroprevalence rate of toxoplasmosis among the Iranian general population was 39.3%.8

Prolactin (PRL) hormone is secreted by pituitary gland which is located below the cerebral cortex. Low levels of this hormone are secreted in blood of female and male individuals and the secretion is under control by PRL inhibitory factors such as dopamine.9 Hyperprolactinemia is a situation in which large amounts of PRL exist in blood of men and pregnant women. The role of PRL has been proven in immune system as PRL receptors are located on the surface of B and T lymphocytes and macrophages and production of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interferon γ (IFNγ), and interleukin-12 (IL-12) are induced by this hormone.10 The inhibitory effects of PRL on proliferation of T. gondii in mononuclear cells of individuals with high levels of PRL have been shown previously.11 The present study was carried out to assess the possible relation between serum PRL levels and frequency of T. gondii infection in humans.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

Men and women aged 15–58 years with no clinical complications participated in this cross-sectional study. A total of 343 blood samples were collected from individuals who had been referred for PRL measurement in medical diagnostic laboratories in Karaj, Iran, from April to September 2016. Demographic characteristics such as sex, age, marital status, and current pregnancy status were recorded through questionnaires. Woman participants who were pregnant/nursing were excluded from the current study. Then, 3 mL of whole blood samples were collected from each of them; the sera were separated and stored at –20°C until use. After collecting samples, concentration of PRL was measured and the samples were divided into cases with high or low levels of PRL and comparison group with normal levels of PRL.

Serological tests

ELISA was designed to detect anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody in blood sera. The cutoff values of ODs were calculated according to Hillyer et al.12 The OD of each sample was compared with the cutoff and recorded as positive or negative result. The cutoff value with 95% CI was determined to be 0.45 for the detection of anti-T. gondii IgG.

Preparation of soluble antigens of T. gondii

Tachyzoites of T. gondii, RH strain was maintained in BALB/c mice with serial passages.13 Tachyzoites that had been inoculated in peritoneal cavity of BALB/c mice were harvested by peritoneal washing with PBS (pH 7.2). The tachyzoites were washed two times with cold PBS, sonicated, and centrifuged at 4°C, 14,000×g for 1 hour. Then, supernatant was collected as soluble antigen, and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford method.

Detection of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody using ELISA technique

Microtiter plates were coated with soluble antigens of T. gondii, RH strain. Sera were added in dilution of 1:100 in PBS followed by incubation and washing. Anti-human IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Dako Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was added after incubation. After washing, chromogenic substrate ortho-phenyline-diamidine (OPD) was added and the reaction was stopped by adding sulfuric acid. The optical density was read and recorded by an automated ELISA reader at 490 nm.14

PRL assessment

Concentration of PRL was measured by Roche Elecsys 2010 analyzer, electrochemiluminescence (ECL) technology for all the collected sera according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In the first step, 10 µL of the samples were incubated with a biotinylated monoclonal PRL-specific antibody. In the second step, a monoclonal PRL-specific antibody labeled with a ruthenium and streptavidin-coated microparticles were added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was aspirated to a measuring cell and the microparticles were magnetically captured on the surface of an electrode. Unbound substances were removed with ProCell/ProCellM. Chemiluminescence was measured by a photomultiplier and the concentration of PRL was determined via a calibration curve.15 Interpretation of the PRL concentration was based on the manufacturer’s recommendation as follows: normal range for men, 86–324 µIU/mL; and for non-pregnant women, 102–496 µIU/mL. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the mean was calculated for each sample.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out according to the principles of Declaration of Helsinki. The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Approval No: 28451) on December 11, 2015. All animal procedures were carried out according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health and approved by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

All participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and the method used did not pose any potential risk and their information will be kept strictly confidential. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before being involved in the study. All participants signed an informed consent and received a complete copy of the signed consent form. In case the person is illiterate, informed consent was obtained by thumbprint and a signature of an impartial witness. Parental consent was obtained from the parents of the minor participants included in this study.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 22.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were analyzed using multiple univariate ANOVA and chi-squared test. Comparison of quantitative variants between two groups was assessed by Student’s t-test. Data description was carried out by calculating frequencies and 95% CIs. Differences were considered as significant when P≤0.05.

Results

Distribution of participants

Of the total participants, 70% (240/343) were women and 30% (143/343) men. The highest frequency of participants (152/343, 43%) were found in the age group of 30–39 years.

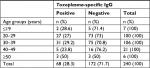

Seroprevalence of anti-Toxoplasma IgG

Of 343 blood serum samples, 110 samples (32%) had anti-Toxoplasma IgG. Participants were divided into five age groups of ≤19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and ≥50 years. According to the age of participants, the prevalence of anti-Toxoplasma IgG in 343 blood serum samples was as follows: ≤19 age group, 3/16 (18.7%); 20–29, 37/124 (29.8%); 30–39, 53/152 (34.9%); 40–49 age group, 12/38 (31.6%); and ≥50 age group, 5/13 (38.5%) (Tables 1 and 2). Of 240 serum samples of women, 68 (28.3%) had anti-Toxoplasma IgG while of 103 serum samples of men 42 (40.8%) had anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody (Tables 1 and 2).

| Table 1 Frequency of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody in 240 blood serum samples of women according to particular age groups by ELISA |

| Table 2 Frequency of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibody in 103 blood serum samples of men according to particular age groups by ELISA |

Serum PRL levels

In total, of 343 serum samples, 171 (49.8%) were considered as normal range of PRL, 16 (4.7%) and 156 (45.5%) samples were considered as hypoprolactinemia and hyperprolactinemia, respectively. The detailed data of serum PRL levels according to the sex of participants are shown in Table 3.

Association of anti-T. gondii IgG antibody and serum PRL levels

According to Tables 4 and 5 the prevalence of T. gondii infection in the groups of women and men with high levels of PRL was lower than the comparison group with normal levels of PRL. The statistically significant differences were found between Toxoplasma seropositivity in women with high levels of PRL and comparison group (P=0.016), but this difference in men with high levels of PRL was not statistically significant (P=0.74). Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were seen between Toxoplasma seropositivity in men and women with low level of PRL and comparison group (P=1). Moreover, in hyperprolactinemia women, by increasing the PRL levels, the prevalence of T. gondii infection decreased.

Discussion

Complex hormonal regulations are necessary for specific immune responses to parasite antigens and effects on interleukins or interferon gamma.16 Proliferation of lymphocytes in primary and secondary lymphoid organs depends on the interactions between PRL and growth hormone. PRL is a hormone secreted by the pituitary gland which is located below the cerebral cortex.17 PRL is produced by the placenta uterus, B and T lymphocytes, and NK cells. B and T lymphocytes and macrophages have PRL receptors. PRL secretion is controlled by PRL inhibitory factors, and both men and women have low levels of this hormone in their blood.18 The situation in which large amounts of PRL are in blood of men or non-pregnant women is called hyperprolactinemia that is fairly common in women.19 Observed differences between men and women in the prevalence of many parasitic infections can indicate the potential role of sex hormones in the immunity against parasites.20 One of the hormones that exhibits a wide range of biological activities, including immunomodulatory effects, is PRL. In this study, we have attempted to explain if there was an association between the level of PRL and the frequency of T. gondii infections among women and men. Preliminary data, comparing the prevalence of T. gondii infection in the population of patients with the PRL level below and above the normal with the population of those having normal PRL level, revealed lower seroprevalence in the group of men and women with hyperprolactinemia. However, differences of Toxoplasma seropositivity in women with high levels of PRL was statistically significant in comparison with the population of those having normal levels of PRL (P=0.016). In addition, in hyperprolactinemia women by increasing of PRL levels, the prevalence of T. gondii infection decreased. No Toxoplasma seropositivity was observed in five serum samples of participants with the highest concentration of PRL.

It has been proven that PRL deficiency in mice may increase the probability and severity of infections. Bromocriptine, the inhibitor of PRL secretion, is used in organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases to inhibit the immune system.21 It is reported that human PRL has the ability to bind with live tachyzoites of T. gondii, RH and ME49 strains.22 It was shown that PRL has the inhibitory effects on Toxoplasma proliferation in mononuclear cells of individuals with high PRL levels. Meli et al in 1996 reported the protective role of PRL against salmonella typhimurium in rat model and found that macrophage phagocytic activity and nitric oxide production increased in the rats that had received PRL.23 Benedetto et al in 2001 showed that PRL can increase the production of interleukins 1 and 6 by microglial cells which stimulate anti-Toxoplasma function in the brain of infected mice.24 Zhang et al in 2002 examined two patients with benign pituitary tumors and found Toxoplasma cyst among these tumor cells. They reported that multiplication of pituitary cells result in PRL production and anti-Toxoplasma activation of microglial cells.25 Moreover, the hypothesis on the protective role of PRL in protozoan infections is additionally supported by Gomez-Ochoa et al.26 They concluded that lactating female hamsters that were infected with Leishmania infantum showed no symptom of infection compared with control group.26 Li et al in 2015 showed that PRL-inducible protein (PIP) can impair Th1 immune response and increase susceptibility to Leishmania major in mice. PIP is a 14 kDa protein that is present in saliva of mice and upregulates by PRL, and it seems that this protein plays a role in host defense against pathogens.27 In the study of Serrano et al in 2009 Neospora seropositive non-aborting cows had more PRL compared with non-infected ones.28 Dzitko et al in 2010 suggested the in vitro effects of recombinant PRL on intracellular replication of T. gondii, BK strain. It seems that PRL has no direct cytotoxic effects on host cells or parasite, but it can probably bind to parasite surface protein and block its receptors.29 In the study conducted by Dzitko et al in women with high PRL levels, T. gondii prevalence was lower than control group (33.9% vs 45.58%).30 PRL receptors are located on the surface of B and T lymphocytes and macrophages and the production of cytokines such as TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-12 is induced by this hormone. The higher levels of TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-12 in hyperprolactinemia patients may be the reason for protecting these individuals against toxoplasmosis. At the last stage of our analysis, the seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in women was 28.3% while this value in men reaches to 40.8% (P=0.038), confirming earlier observations carried out on several parasitic diseases. Similar results reported a higher prevalence and intensity of infections for men than for women in the case of protozoan parasites such as Entamoeba histolytica, Leishmania donovani, Leishmania braziliensis, and Plasmodium falciparum.31–34 The overall anti-Toxoplasma IgG prevalence was 32% in this study. The prevalence of toxoplasmosis in the general population of this area was 45.5% according to the study by Keshavarz et al in 1998.35 The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis among women and men was also estimated in relation to the age of the patients. The highest toxoplasmosis seroprevalence for men and women was found in 30–39 and ≥50 years age group, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). These data were in accordance with the range of general seropositivity expected for Iranian general population.8

Conclusion

The results of the current study confirmed the previous studies based on immunoregulatory role of PRL and indicated that high levels of PRL could be related to T. gondii seronegativity in women.

Data sharing statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to the privacy of the individuals’ identities. The dataset supporting the conclusions is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, New York: CRC Press Inc.; 2010:1–313. | ||

Tavalla M, Oormazdi H, Akhlaghi L, et al. Genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii Isolates from Soil Samples in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8(2):227–233. | ||

Weiss LM, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39(8):895–901. | ||

Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(12-13):1217–1258. | ||

Ali-Heydari S, Keshavarz H, Shojaee S, Mohebali M. Diagnosis of antigenic markers of acute toxoplasmosis by IgG avidity immunoblotting. Parasite. 2013;20:18. | ||

Sharbatkhori M, Dadi Moghaddam Y, Pagheh AS, Mohammadi R, Hedayat Mofidi H, Shojaee S. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infections in Pregnant Women in Gorgan City, Golestan Province, Northern Iran-2012. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9(2):181–187. | ||

Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé ML. Epidemiology and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(2):264–296. | ||

Daryani A, Sarvi S, Aarabi M, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in the Iranian general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Trop. 2014;137:185–194. | ||

Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1523–1631. | ||

Roberts CW, Walker W, Alexander J. Sex-associated hormones and immunity to protozoan parasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(3):476–488. | ||

Dzitko K, Lawnicka H, Gatkowska J, Dziadek B, Komorowski J, Długońska H. Inhibitory effect of prolactin on Toxoplasma proliferation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with hyperprolactinemia. Parasite Immunol. 2012;34(6):302–311. | ||

Hillyer GV, Soler de Galanes M, Rodriguez-Perez J, et al. Use of the Falcon assay screening test-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (FAST-ELISA) and the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) to determine the prevalence of human fascioliasis in the Bolivian Altiplano. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46(5):603–609. | ||

Teimouri A, Azami SJ, Keshavarz H, et al. Anti-Toxoplasma activity of various molecular weights and concentrations of chitosan nanoparticles on tachyzoites of RH strain. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1341–1351. | ||

Shojaee S, Teimouri A, Keshavarz H, Azami SJ, Nouri S. The relation of secondary sex ratio and miscarriage history with Toxoplasma gondii infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):307. | ||

Teimouri A, Modarressi MH, Shojaee S, et al. Detection of toxoplasma-specific immunoglobulin G in human sera: performance comparison of in house Dot-ELISA with ECLIA and ELISA. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(8):1421–1429. | ||

Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;5:491. | ||

Dorshkind K, Horseman ND. The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(3):292–312. | ||

Soares MJ. The prolactin and growth hormone families: pregnancy-specific hormones/cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:51. | ||

Mancini T, Casanueva FF, Giustina A. Hyperprolactinemia and prolactinomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37(1):67–99. | ||

Roberts CW, Walker W, Alexander J. Sex-associated hormones and immunity to protozoan parasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(3):476–488. | ||

McMurray RW. Bromocriptine in rheumatic and autoimmune diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;31(1):21–32. | ||

Galván-Ramírez ML, Gutiérrez-Maldonado AF, Verduzco-Grijalva F, Jiménez JM. The role of hormones on Toxoplasma gondii infection: a systematic review. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:503. | ||

Meli R, Raso GM, Bentivoglio C, Nuzzo I, Galdiero M, Di Carlo R. Recombinant human prolactin induces protection against Salmonella typhimurium infection in the mouse: role of nitric oxide. Immunopharmacology. 1996;34(1):1–7. | ||

Benedetto N, Folgore A, Romano Carratelli C, Galdiero F. Effects of cytokines and prolactin on the replication of Toxoplasma gondii in murine microglia. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2001;12(2):348–358. | ||

Zhang X, Li Q, Hu P, Cheng H, Huang G. Two case reports of pituitary adenoma associated with Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(12):965–966. | ||

Gomez-Ochoa P, Gascon FM, Lucientes J, Larraga V, Castillo JA. Lactating females Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) show protection against experimental Leishmania infantum infection. Vet Parasitol. 2003;116(1):61–64. | ||

Li J, Liu D, Mou Z, et al. Deficiency of prolactin-inducible protein leads to impaired Th1 immune response and susceptibility to Leishmania major in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(4):1082–1091. | ||

Serrano B, López-Gatius F, Santolaria P, et al. Factors affecting plasma pregnancy-associated glycoprotein 1 concentrations throughout gestation in high-producing dairy cows. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44(4):600–605. | ||

Dzitko K, Gatkowska J, Płociński P, Dziadek B, Długońska H. The effect of prolactin (PRL) on the growth of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites in vitro. Parasitol Res. 2010;107(1):199–204. | ||

Dzitko K, Malicki S, Komorowski J. Effect of hyperprolactinaemia on Toxoplasma gondii prevalence in humans. Parasitol Res. 2008;102(4):723–729. | ||

Acuna-Soto R, Maguire JH, Wirth DF. Gender distribution in asymptomatic and invasive amebiasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(5):1277–1283. | ||

Goble FC, Konopka EA. Sex as a factor in infectious disease. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1973;35(4 Series II):325–346. | ||

Jones TC, Johnson WD Jr, Barretto AC, et al. Epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis braziliensis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156(1):73–83. | ||

Landgraf B, Kollaritsch H, Wiedermann G, Wernsdorfer WH. Parasite density of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Ghanaian schoolchildren: evidence for influence of sex hormones? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88(1):73–74. | ||

Keshavarz H, Nateghpour M, Zibaei M. Seroepidemiologic survey of Toxoplasmosis in Karaj district. Iranian J Pub Health. 1998;27(3–4):73–82. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.