Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

The Paradoxical Effects of the Contagion of Service-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Authors Guo G, Jia Y, Mu W, Wang T

Received 28 September 2021

Accepted for publication 18 January 2022

Published 22 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 405—424

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S341068

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Gengxuan Guo,1 Yu Jia,2 Wenlong Mu,3 Tao Wang4

1School of Business, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Journalism and Communication, Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Economics and Management, Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei, People’s Republic of China; 4Research Center for Organizational Marketing of Wuhan University, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yu Jia, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Previous research on the service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of employees has mainly focused on the examination of its driving factors, and has ignored the consequences that it may bring to the workplace. To bridge this research gap, by shifting the focus to the event observers, a double-edged sword model is constructed in the present study, which helps explain whether, when, and why the service-oriented OCB of coworkers is contagious.

Methodology: Multi-wave data of 239 employees from seven service-oriented companies in the hospitality industry in central and southwestern China were used to support the proposed model. The time-lag method and critical incident techniques were introduced during the data collection stage. OLS regression and the bootstrapping method were employed for hypothesis testing.

Findings: Drawing on attribution theory, it is argued that the contagion (vs non-contagion) effects of service-oriented OCB work through the dual cognitive pathways (hypocrisy perception vs serving self-efficacy) of observers, which depend on the self-serving attribution of the observers to the behaviors of their coworkers. Specifically, when the self-serving attribution of observers is high, the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers is positively associated with the hypocrisy perception of the observers, which in turn inhibits their own service-oriented OCB. In contrast, when the self-serving attribution of observers is low, the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers is positively associated with the serving self-efficacy of the observers, which in turn promotes their service-oriented OCB. This framework provides a valuable theoretical explanation perspective and empirical evidence for the exploration of how service-oriented OCB affects observers.

Keywords: contagion, service-oriented OCB, attribution

Introduction

Currently, the service industry is playing an increasingly important role in the development of the global economy.1,2 The service quality of employees is a vital source for enterprises to gain competitive advantage; enterprises with higher service quality will establish a heterogeneous advantage as compared to other competitors. Against this background, the service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of employees is receiving increasingly more attention from service industry practitioners and scholars.3,4 Service-oriented OCB can be defined as the discretionary behaviors of employees that go beyond the requirements of their roles during the service process.5,6

Previous studies have extensively discussed the service-oriented OCB of employees, and can be roughly divided into the following three perspectives. First, the literature has reached a consensus on the necessity of service-oriented OCB to help promote the overall service quality, competitive advantage, and financial performance of hospitality enterprises.7–9 Second, scholars have discussed the driving factors of service-oriented OCB; factors such as the organization’s service climate, supervisory support climate, and high-performance human resource management system are all important antecedent variables of service-oriented OCB.5,6,10–12 The third perspective is primarily based on the viewpoint of employee-customer interaction; service-oriented OCB has been considered to provide more innovative service ideas, establish better customer interaction, provide better service quality, and yield higher customer satisfaction.13,14

Relatively rich research has been carried out on service-oriented OCB. However, previous studies have rarely considered the consequences of service-oriented OCB, especially in the workplace. Employees often work with colleagues, so their behaviors are often accompanied by some witnesses. Furthermore, the behavior observers in the workplace often occupy the majority position, which means that the positive behaviors of employees may have a “role model” effect and drive a positive atmosphere at the team level.15 In other words, within an organization, the service-oriented OCB of a small number of employees may stimulate the OCB of a larger number of employees, which will significantly promote the company’s service performance. However, this type of learning effect may also be counterproductive. For example, when subordinates attribute a supervisor’s humility to self-service, not only will they not show humility, but they will engage in deviant behavior.16 This means that the contagion effects of the behavior of employees may be dualistic (promote vs inhibit). Thus, is this the case for service-oriented OCB? Regrettably, the existing literature has ignored this topic. Therefore, the primary research question of the present study is raised as follows.

From the observer-centric perspective, does, when will, and how will the double-sword edge effect of the contagion of service-oriented OCB exist among colleagues?

To bridge this research gap, the current study investigates the impact of service-oriented OCB on observers from an observer-centric perspective. Specifically, drawing on attribution theory,17 a double-edged sword model is constructed, which helps explain whether, when, and why the contagion (vs non-contagion) effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers exists. Attribution theory clarifies how observers make causal explanations for the behavior of themselves and others.18–20 Service-oriented OCB can be viewed as either beneficial or detrimental behavior, which depends on whether the attributed motive for the behavior is driven by an authentic focus on helping others or a focus on only improving the image of oneself.21 Therefore, the cognitive judgments of employees depend on their attributions of the events they observe. Previous studies have shown that observers are more likely to make negative attributions (such as self-serving, eg, focusing on the image needs of the individual) to the OCB of coworkers.22 Based on the preceding analysis, it is argued in the present study that the self-service attribution of observers determines their different cognitive judgments of, and behavioral responses to, service-oriented OCB. Specifically, when observers have a high level of self-serving attributions about such positive behaviors, they tend to have hypocrisy perceptions, which will further inhibit their willingness to implement service-oriented OCB. On the contrary, when observers have a low of level self-serving attributions about positive behaviors, they tend to produce serving self-efficacy, which will further promote their willingness to implement service-oriented OCB. In summary, the present study aims to investigate the specific mechanism of the contagion (vs non-contagion) effect of service-oriented OCB. The theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model of the current research. |

The present study provides several theoretical implications for service-oriented OCB and attribution theory. First, based on the observer-centric perspective, the current study is the first to explore the impact of service-oriented OCB on observers. A contagion (vs non-contagion) model of employees’ service-oriented OCB is constructed; this compensates for the lack of actor-based perspectives in previous studies of service-oriented OCB, and provides a more comprehensive perspective for understanding the impact of proactive behaviors. Second, the proposed double-edged sword model helps to balance the contradictory views of previous research. By introducing the logic of dialectics into the research of service-oriented OCB, the current study explains why contradictory views exist, and provides a more complete and dialectical theoretical perspective for the relevant literature from the observer-centric perspective. Third, by identifying new factors that promote and inhibit the service-oriented OCB of employees, the current study further expands the relevant literature in the field of service-oriented OCB. Finally, a dual-pathway framework (hypocrisy perception vs serving self-efficacy) is identified, via which the contagion (vs non-contagion) of service-oriented OCB occurs. This framework provides a valuable theoretical explanation perspective and empirical evidence for the exploration of how service-oriented OCB affects observers.

Theoretical Grounding and Hypothesis Development

Attribution Theory

A key element in explaining human behavior is the attribution of the motivation for that behavior.23–25 Attribution theory clarifies how observers make causal explanations for the behavior of themselves and others,18–20 which suggests that individuals’ perceptions of the causes of past events will affect their own attitudes about and motivation toward future events, and they will then adjust their behavioral responses according to the social environment.26,27 In addition, the formation of attribution is based on the behavioral information available to observers, rather than objective facts.28 Therefore, individuals can make internal or external attributions based on the control points (factor sources), stability, and controllability that affect others’ behavior to help them better understand, predict, and control events.19

Based on the preceding discussion on attribution theory, observers’ attitudes about and responses to the behavior of their colleagues depend on their attribution of the motivation behind the behavior. In addition, emerging research has shown that the proactive OCB of coworkers may lead to the negative perceptions of observers, such as impression management attribution.29–31 Therefore, the motivation of coworkers for service-oriented OCB may be different from that of observers, which means that proactive and extra-role behavior may also result in some negative feedback effects.

Observers’ Self-Serving Attribution for Coworkers’ Service-Oriented OCB

Attribution theory proposes that individuals construct causal explanations for others’ behavior to understand their environment.17 Correspondingly, individuals (such as observers) will interpret and assess their coworkers’ behavior in line with these explanations. Therefore, an individual’s cognition of the behavior of others depends on the motivational attribution of that behavior.19 Service-oriented OCB, which has gone beyond the basic work requirements, refers to the spontaneous behavior of front-line employees outside of their formal role when serving customers.3 Research has shown that observer employees in the third-party perspective are more likely to make negative (eg, self-serving motive) attributions about the OCB of their coworkers.22 The self-serving motive focuses on the image needs of the individual self. As such, the same performance of service-oriented OCB can be viewed as either beneficial or detrimental behavior, which depends on whether the attributed motive for the behavior is driven by an authentic focus on helping others or a focus on only improving the image of oneself.21 For example, one observer may view the early arrival of a coworker as showing concern for the organization, but another coworker may regard this same behavior as motivated by impression management.

There is a key difference between acting in a more authentic way and acting in an instrumental way.32,33 Therefore, the good behavior of coworkers may be considered negative when the behavior is attributed to instrumental (self-serving) motivation by the observer.34,35 Based on the preceding discussion, the current study aims to explore the different cognition and behavioral reactions of observers under different self-serving motivation attribution levels of their coworkers as perceived by the observer. By adopting the perspective of the perceptions of individuals, which focuses on how employees interpret information about their coworkers and draw conclusions about them, light can be shed on how the behavior of coworkers, such as service-oriented OCB, is perceived.

The Non-Contagion of Service-Oriented OCB: The Instrumentality Mechanism

The Interactive Effect of Coworkers’ Service-Oriented OCB and Observers’ Self-Serving Attribution on Observers’ Hypocrisy Perception

Drawing on attribution theory, it is argued that when observers attribute the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers to impression management, ie, the OCB of coworkers is perceived as self-serving, the service-oriented OCB of the coworkers may induce the hypocrisy perception of the observers. Attribution theory suggests that when employees observe a novel behavior, they will form attributions to understand this behavior.36 Service-oriented OCB, which consists of the three behaviors of service delivery, loyalty, and participation, refers to the citizenship behaviors toward customers performed by service employees.37 From this perspective, as a type of OCB, service-oriented OCB can be regarded as a tool with which actors can obtain organizational resources, such as high-level leader-member exchange (LMX), the trust of supervisors, etc.38,39 In public, coworkers may engage in service-oriented OCB to service customers, but in private, they may be self-interested in gaining the trust of their supervisors, which may lead to inconsistencies in their service-oriented OCB. Similarly, studies have shown that the behaviors displayed by individuals may not always be consistent.40,41

Service-oriented OCB refers to an employee’s proactive service behavior toward consumers, which is a consumer-oriented behavior; however, scholars have also pointed out the detrimental motivation of conducting such behavior to impress others (such as supervisors and observers).42–44 This evaluation of the motives of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may be labeled as self-serving, ie, a type of impression management. Specifically, when observers make self-serving attributions about the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers, they are interpreting that the coworkers are engaging in such behavior instrumentally, rather than authentically, with the goals of influencing the way that others view them and maintaining a hardworking and capable image in the eyes of others (eg, consumers, supervisors, and observer employees). Correspondingly, the observers may associate the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers with some negative perceptions and regard their behavior as hypocritical.

In addition, when observers make self-serving attributions about the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers, they may consider that their coworkers are acting in an instrumental way instead of a more authentic way. The connotation of authenticity depends on the context in which the observers witness their coworkers’ behaviors, which means that “authenticity” is a socially constructed variable.45 Similarly, studies have shown that authenticity does not necessarily exist objectively; on the contrary, it is often a motivational attribution of individuals to others.46 Therefore, it is suggested that when observers make self-serving attributions about the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers, they are implying that the behavior of their coworkers is a political tactic and not authentic, which may lead to the perception of the behavior as hypocritical. Furthermore, based on the definition of this construct, service-oriented OCB is a proactive service behavior of employees toward consumers. Therefore, the recipients of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers are not observer employees.47 This means that observers cannot directly benefit from the behaviors of coworkers, which may further result in the inconsistent perceptions of observers between their attributions and their coworkers’ actual behavior. Under these circumstances, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may be considered equivalent to impression management tactics, via which the coworkers desire to be seen as hardworking and capable.

Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1: The service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers will interact to influence the hypocrisy perception of the observers. The relationship between the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the hypocrisy perception of observers will be stronger and positive when the self-serving attribution of the observers is high, but will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is low.

The Mediating Role of the Hypocrisy Perception of Observers

The reactions of observers when they attribute the service-oriented OCB of coworkers to hypocrisy are subsequently examined. Drawing on attribution theory, once an employee has formed a certain explanation for the behavior of others (eg, perceiving the service-oriented OCB of coworkers as hypocrisy), the employee will rely on this explanation to make his/her own behavioral decisions.48,49 Therefore, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may also convey some hypocrisy information.Previous studies have shown that individuals tend to feel discomfort when they regard the behavior of their teammates as hypocritical.50 For example, Cha and Edmondson51 suggested that hypocrisy perception will positively predict the moral disengagement of an individual; an individual produces certain specific cognitive tendencies and uses these tendencies to adjust their inherent responsibility attribution to minimize the responsibilities of the actors themselves regarding behavioral consequences.52 Employees with a high level of moral disengagement tend to redefine their behaviors to find a moral norm for their unethical behaviors, and to ultimately protect themselves from the rebuke of their moral self.53 In other words, when observers have a high level of self-serving attributions about the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers, they may regard the behavior as hypocrisy, which may not make moral norms stand out; in contrast, it may set a bad example for observers (the hypocrisy cognition of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers), and give them reasons for moral disengagement, such as the inhibition of their own service-oriented OCB.54 Similarly, the emerging research has shown that the hypocrisy perception of the humility of supervisors may inhibit the OCB of subordinate employees.

Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: Hypocrisy perceptions of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers mediate the relationship between the interactive effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of the service-oriented OCB of observers. The indirect effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers on the service-oriented OCB of observers via their hypocrisy perceptions will be strong and positive when the self-serving attribution of the observers is high, and will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is low.

The Contagion of Service-Oriented OCB: The Authenticity Mechanism

The Interactive Effect of Coworkers’ Service-Oriented OCB and Observers’ Self-Serving Attribution on Observers’ Serving Self-Efficacy

Drawing on the service-oriented OCB literature55 and attribution theory,19,27 it is suggested that the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may also lead to an overall increase in the serving self-efficacy of observers, especially when observers attribute the service-oriented OCB of coworkers to a low self-serving manner. Serving self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in his/her or capabilities to engage in serving behaviors that can benefit the consumers.56,57 Previous studies have shown that the self-efficacy of individuals can be enhanced by witnessing workplace events.58 The impact of this path depends on the observers’ perception of the event.59,60

Specifically, when observers attribute the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers to a low self-serving manner, they may be more inclined to think that their coworkers are acting with authentic motivation. In other words, observers in this attribution situation may consider that their coworkers are taking actions to improve the service quality by communicating with the organization, exhibiting attentive service performance to consumers, and promoting the image of the organization.37 Meanwhile, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may bring high-level performance, customer satisfaction, and loyalty to the organization.61,62 Such cognition, namely vicarious learning, enables observers to learn the behaviors of their coworkers, which helps them avoid spending unnecessary effort on unnecessary trials.63 Vicarious learning includes the stages of attention, retention, and reproduction, which respectively refer to the observer’s behavior awareness, ability to remember behavior, and ability to repeat behavior.64 The vicarious learning process provides observers with a mental script to repeat the witnessed service-oriented OCB of their coworkers.65

Previous studies have shown that vicarious learning can help promote individual self-efficacy beliefs.66 Therefore, it is further suggested that individuals who observe their coworkers engaging in service-oriented OCB may feel more confident about the effectiveness of their own service-oriented OCB, and may be more likely to consider that their own service-oriented OCB can provide consumers with high-level service quality and improve the organization’s performance. Witnessing the engagement of coworkers in service-oriented OCB may provide the observers, especially those with a low level of self-serving attribution, with a cognitive schema that mentally guides them in their attempts to undertake service-oriented OCB. This socially constructed confidence is especially necessary for service-oriented OCB, which is often associated with immense social risks, as it may disturb others.67 Therefore, exemplification by coworkers is critical to the construction of the serving self-efficacy beliefs of observers.

Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3: The service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers will interact to influence the serving self-efficacy of observers. The relationship between the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the serving self-efficacy of observers will be stronger and positive when the self-serving attribution of observers is low, and will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is lower.

The Mediating Role of Observers’ Serving Self-Efficacy

Drawing on attribution theory, as the witnesses of the behavior of their coworkers, observers tend to adjust their behaviors according to their attribution of the service-oriented OCB of their coworkers.68 As such, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers plays a crucial role in demonstrating serving behaviors to observers via observational learning, which may influence the observers’ confidence and ability to identify the consumers’ needs and serve them proactively.69 Therefore, it is first proposed that the service-oriented OCB of coworkers plays a vital role in instilling serving self-efficacy to observers with a low level of self-serving attribution.Self-efficacy has been considered a potential psychological mechanism that drives employee performance improvement.56 In addition, the implementation of proactive behavior (including service-oriented OCB) is socially risky, so individuals must be confident to implement this behavior.70 The confidence of an individual in a certain behavior will encourage him/her to implement that behavior.57,58 Therefore, consistent with the self-confidence nature presented in the definition of self-efficacy, observers with a high level of serving self-efficacy are more inclined to engage in service-oriented OCB.71 Similarly, emerging research has shown that when employees witness the voice behavior of their coworkers, their own voice self-efficacy beliefs will be enhanced, which will further trigger their voice behavior.72 Taken together, it is suggested that serving self-efficacy serves as a conduit that transmits the interaction between the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers into their own service-oriented OCB.

Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 4: The serving self-efficacy of observers mediates the relationship between the interactive effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers on the service-oriented OCB of observers. The indirect effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers on the service-oriented OCB of observers via their serving self-efficacy will be strong and positive when the self-serving attribution of observers is low, and will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is high.

Methods

Samples and Procedure

Since the over-arching theory of present study is attribution theory, we should test our model at the individual-level.73 In the sample collection phase, we used the critical incident technique method, which can effectively evaluate the employees’ perception and response to specific events.74,75 Previous studies have shown that service-oriented OCB occurs in the service industry, so we collected samples from 7 hotels in central and southwestern China.55,61 Furthermore, to better control the common method variance, a time-lag longitudinal tracking research design was adapted for data collection. Specially, the participants were asked to report the core variables at intervals. Our field survey was completed in three phases, with two weeks between each phase, for a total of four weeks. The specific process is as follows.

Before the formal survey, all the participants were asked to recall their coworker C’s service-oriented OCB in the past month as much as possible. After the incident was reviewed, we formally started the questionnaire survey. In the first stage, the participants were asked to report demographic information and the coworker C’s service-oriented OCB observed by themselves. 350 questionnaires were distributed and 305 were effectively returned. Two weeks later, we started the second investigation, and the previous valid questionnaires were distributed again. This time, we mainly investigated the employees’ (serving self-efficacy and hypocrisy perception) cognitive judgment. 305 questionnaires were distributed and 267 were effectively returned. After another two weeks, the last investigation was conducted. Employees reported their own service-oriented OCB and self-serving attribution. In summary, 267 questionnaires were distributed and 239 were effectively returned. The remaining 28 questionnaires were discarded because they were not completed.

Measures

Coworkers’ Service-Oriented OCB

In order to measure the coworkers’ service-oriented OCB observed by employees, we refer to the scale developed by Bettencourt et al.37 The participants were asked to score their coworkers’ service-oriented OCB (1 for strongly disagree, 5 for disagree). One example item is: “My colleague C will follow up customer requests and problems in time.” We calculated the Cronbach’s alpha (α) to evaluate the internal consistency reliability of the scale, wherein a value of 0.70 or above is suggested to ensure internal consistency reliability.76 In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency reliability (α = 0.984).

Observers’ Hypocrisy Perception

In order to measure the observers’ hypocrisy perception, we refer to the scale developed by Dineen et al.77 The participants were asked to score their coworkers’ hypocrisy (1 for strongly disagree, 5 for disagree). One example item is: “I hope my colleague C will practice what he preached more.” The scale had excellent internal consistency reliability (α = 0.951).

Observers’ Serving Self-Efficacy

In order to measure the observers’ serving self-efficacy, we refer to the scale developed by Wu et al.57 The participants were asked to score their serving self-efficacy (1 for strongly disagree, 5 for disagree). One example item is: “I think I can put the best interests of consumers ahead of my own.” The current study had an alpha value of 0.960 indicating excellent internal consistency reliability.

Observers’ Self-Serving Attribution

Following the previous study, self-serving attribution here means observers’ impression management attributions.32,42 In order to measure the observers’ self-serving attribution, we refer to the scale developed by Rioux and Penner.78 The participants were asked to score their self-serving attribution (1 for strongly disagree, 5 for disagree). One example item is: “My coworker C behave nicely for it may make him look good to the supervisor.” The scale yielded an alpha value of 0.969 indicating excellent internal consistency reliability.

Observers’ Service-Oriented OCB

In order to measure the observers’ service-oriented OCB, we refer to the scale developed by Bettencourt et al.37 The participants were asked to score their own service-oriented OCB (1 for strongly disagree, 5 for disagree). One example item is: “I will follow up customer requests and problems in time.” The scale exhibited excellent internal consistency reliability (α = 0.992).

Control Variable

In addition, previous studies have shown that some background variables (such as age, gender, education level and tenure) are also important factors affecting employees’ service-oriented OCB.11,55 Therefore, this study intends to put the gender (1 for male, 2 for female), age (coded with 1 to 5, respectively, representing 20 years and below, 21–25 years, 26–35 years, 36–45 years, 46 and above), education level (1 for below senior high school, 2 for senior high school, 3 for junior college, 4 for bachelor, 5 for master and above), tenure (1 for 1 year and below, 2 for 1–3 years, 3 for 3–5 years, 4 for 5–7 years, 5 for 7 years and above) and jobs (1 for hotel room related jobs, 2 for hotel reception, 3 for catering related jobs, 4 for marketing related jobs, 5 for the others) as the control variables of this study, which were reported by employees themselves.

Analytic Strategy

To verify our four hypotheses, quantitative methods were performed including descriptive statistics, inter-correlations analysis, verification of statistical hypotheses, and multivariable approaches.79,80 Multivariable approaches included multiple regression, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).81,82 Additionally, Bootstrap method and Johnson-Neyman method were also adopted to test our hypotheses. The specific analysis strategies are as follows.

Before testing the hypothesis, we performed two preliminary analyses. First, considering that the core variables in this paper were all reported by the observers themselves, the empirical results may be affected by the common method variance. Two main methods were proposed to control possible common method variance: (a) strengthening the research design and (b) employing statistical controls.83,84 In this study, we have adopted a time-lag longitudinal tracking research design to reduce common method variance. As for statistical controls, Harman’s single-factor test is widely used to examine common method variance.85 Based EFA with all study variables, the common method variance is not an issue if the first unrotated factor accounts for less than 50% of the variance in data.86 Second, we adopted model fit comparison techniques to test the discriminant validity of the five study variables. Based on the CFA, we compared the five-factor model against the other five alternative models, including a four-factor model that combined observes’ hypocrisy perception and observers’ serving self-efficacy, a four-factor model that combined observers’ serving self-efficacy and observers’ self-serving attribution, a four-factor model that combined observes’ hypocrisy perception and observers’ self-serving attribution, a three-factor model that combined observes’ hypocrisy perception, observers’ serving self-efficacy, and observers’ self-serving attribution, and a single-factor model combined all the five variables. Model fit was evaluated by several commonly used indices.87–89 chi square (χ2, χ2/df < 3, for acceptable), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90 for acceptable), standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR, < 0.08 for acceptable), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA, < 0.08 for acceptable).

Subsequently, we began to test our hypotheses. First, inter-correlations coefficients of all variables were calculated. Second, multiple regressions were performed. Finally, we further used process macro to test the moderated mediating effect.90 Specifically, we measured the difference of indirect effects between higher (+1 standard deviation) and lower (−1 standard deviation) level moderators (observers’ self-serving attribution).91

In generalizing conclusions, we adopted a flexible method to the assumed significance level.80,92 Specifically, significance level below 0.05 was conventionally used, but sometimes significance level below 0.10 was used.

Results

Common Method Variance

We performed EFA according to the Harman’s single factor method to analyze all the items in the questionnaire and separate the unrotated common factors. The results show that there are 5 factors with a characteristic root greater than 1. The first factor accounts for 38.724% of the total load of all factors, and the total explained variance is 85.092%. Therefore, the result meets the requirement that the maximum extracted variance should be less than the 50% critical value of the total explained variance, which indicates that the common method variance of this study is within an acceptable range and the empirical test can be continued.

Discriminant Validity

A series of confirmatory factor analysis was conducted before the hypothesis testing, which may help to ensure that the discriminant validity of our core constructs (coworkers’ service-oriented OCB, observers’ service-oriented OCB, serving self-efficacy, hypocrisy perception and self-serving attribution) meets the requirements. Based on the comparison among the follow six models in Table 1, the indices of the five-factor model all pass the threshold standard, and are significantly better than other models, which indicates that the variables have discriminant validity.

|

Table 1 Model Fit Results for Confirmatory Factor Analyses |

Hypothesis Testing

Table 2 depicts the correlation analysis results . According to theTable 2, there are significant correlated relationships between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB, observers’ service-oriented OCB, serving self-efficacy, hypocrisy perception. The correlation between these variables is basically consistent with the theoretically expected relationship of this study, which also lays the foundation for subsequent hypothesis testing.

|

Table 2 Correlation analysis |

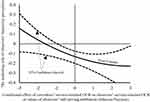

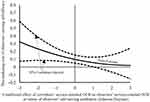

We further conducted a series of multiple regressions to test our model. Table 3 presents the results for Hypothesis 1. As shown in model 3 in Table 3, the interaction between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ self-serving attribution has a significant positive effect in predicting the observers’ hypocrisy perception (b = 0.190, t = 3.210, P < 0.01). As shown in Figure 2, a simple slope analysis shows that, the relationship between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ hypocrisy perception will be strong and positive when observers’ self-serving attribution is high, but weaker when observers’ self-serving attribution is low. Therefore, hypothesis 1 is verified. Similarly, as shown in model 3 in Table 4, the interaction between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ self-serving attribution has a significant negative effect on the prediction of observers’ serving self-efficacy (b = −0.116, t = −1.903, P < 0.1). As shown in Figure 3, a simple slope analysis shows that, the relationship between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ serving self-efficacy will be strong and positive when observers’ self-serving attribution is low, but weaker when observers’ self-serving attribution is high. Therefore, hypothesis 2 has also been verified.

|

Table 3 Regression Results for the Predictors of Observers’ Hypocrisy Perception |

|

Table 4 Regression Results for the Predictors of Observers’ Serving Self-Efficacy |

|

Figure 2 The moderating role of observers’ self-serving attribution on the relationship between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ hypocrisy perception. |

|

Figure 3 The moderating role of observers’ self-serving attribution on the relationship between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ serving self-efficacy. |

In order to test the moderated mediating effects of hypothesis 3 and 4, we first test the significance level between the mediating variables (hypocrisy perception and serving self-efficacy) and the dependent variable (observers’ service-oriented OCB). The results are demonstrated in Table 5. As shown in model 2 in Table 5, there is a significant negative relationship between observers’ hypocrisy perception and their service-oriented OCB (b = −0.328, t = −5.518, P < 0.01), there is a significant positive relationship between the observers’ serving self-efficacy and their service-oriented OCB (b = 0.309, t = 5.364, P < 0.01). This laid a preliminary foundation for the test of moderated mediating effects. Furthermore, we use Process Macro program and Bootstrap method for the further test. As shown in Table 6, with the observers’ self-serving attribution from one standard deviation below the average to one standard deviation above the average, the mediating effect of observers’ hypocrisy perception increases significantly in turn, and the whole model is significant (index = −0.0575, 95% CI [−0.1131, −0.0146]). Next, referring to the suggestion of Hayes and Matthes,90 we used Johnson-Neyman method to draw the mediating effect map.93,94 As shown in Figure 4, among the regions of significance in the range of the moderator (observers’ self-serving attribution), the mediating role of observers’ hypocrisy perception between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ service-oriented OCB was significant, which means that the indirect effect of coworkers’ service-oriented OCB on observers’ service-oriented OCB via observers’ hypocrisy perception will be strong and positive when observers’ self-serving attribution is high and will be weaker when observers’ self-serving attribution is low. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is supported. As shown in Table 6, with the observers’ self-serving attribution from one standard deviation below the average to one standard deviation above the average, the mediating effect of observers’ serving self-efficacy is significantly weakened in turn, and the whole model is significant (index = −0.0451, 95% CI [−0.0871, −0.0016]). Furthermore, it is indicated by the mediating effect diagram with regulation in Figure 5, among the regions of significance in the range of the moderator (observers’ self-serving attribution), the mediating role of observers’ serving self-efficacy between coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and observers’ service-oriented OCB was significant, which means that the indirect effect of coworkers’ service-oriented OCB on observers’ service-oriented OCB toward victims via observers’ serving self-efficacy will be strong and positive when observers’ self-serving attribution is low and will be weaker when observers’ self-serving attribution is high. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

|

Table 5 Regression Results for the Predictors of Observers’ Service-Oriented OCB |

|

Table 6 Bootstrap Results for the Moderated Mediation Effect |

|

Figure 4 Conditional effect of coworkers’ service-oriented OCB on observers’ service-oriented OCB at values of observers’ self-serving attribution (observers’ hypocrisy perception as mediator). |

|

Figure 5 Conditional effect of coworkers’ service-oriented OCB on observers’ service-oriented OCB at values of observers’ self-serving attribution (observers’ serving self-efficacy as mediator). |

Discussion

The theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and future research prospects are subsequently discussed based on the findings of the previous sections.

Theoretical Implications

This research has several important theoretical implications for the extant literature on service-oriented OCB, serving self-efficacy, hypocrisy perception, and attribution theory.

First, based on the observer-centric perspective, the present study was the first to explore the impact of service-oriented OCB on observers. Previous research on service-oriented OCB mainly focused on its antecedent variables. For example, studies have shown that factors such as hotel customer-employee exchange, the organization service climate, the supervisory support climate, and high-performance human resource practices are all important driving factors for the service-oriented OCB of employees.5,6,10,11 The role stressors will inhibit employees from implementing service-oriented OCB.95 However, these previous studies paid less attention to the outcome variables of service-oriented OCB. Moreover, very few studies that explored the outcome variables of service-oriented OCB exclusively focused on the perspective of the behavior recipient, ie, the exploration of the benefits of the behavior to the others, such as consumers and organizations.61 Furthermore, few investigations have focused on the impacts of employees’ adoption of service-oriented OCB on third parties (observers), which urgently require deeper insights. Although the impacts of service-oriented OCB on the observers are indirect effects, they often reflect the “majority effect” in reality, ie, the third parties are usually the majority, but the behavior recipients may be the minority.15

To bridge this research gap, by utilizing an observer-centric perspective, a contagion (vs non-contagion) model of the service-oriented OCB of employees was constructed in the present study, which expanded the research of service-oriented OCB to behavior observers. The theoretical model compensates for the lack of actor-based perspectives in previous studies on service-oriented OCB, and provides a more comprehensive perspective for understanding the impacts of proactive behaviors. Furthermore, based on attribution theory, an in-depth exploration of the internal mechanism and boundary conditions of the contagion (vs non-contagion) effects of service-oriented OCB was conducted. Specifically, the dual cognition (serving self-efficacy vs hypocrisy perception) of employees plays a mediating role, and their self-serving attribution plays a moderating role, which provides an important theoretical explanation and empirical evidence for revealing the mechanism of the impact of service-oriented OCB on observers. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to shift focus to the behavior of observers in the investigation of the consequences of the service-oriented OCB of employees, which will greatly enrich the understanding of this pro-social behavior.

Second, and more importantly, previous research based on the observer-centric perspective has been controversial. Specifically, some studies have found that some behaviors that are widely considered to have positive effects (ie, voice, high-level creativity, etc.) have important positive impacts on the observers themselves, while other studies have suggested that these positive behaviors have negative impacts on the observers. For example, Ng et al72 argued that witnessing the voice of a coworker may promote observers to engage in this voice. On the contrary, other studies have shown that employees with a high level of creativity may cause the envy of, and ostracism by, their coworkers.96,97 Therefore, previous studies have overlooked the boundary conditions under which positive behaviors take effect. With regards to this, a double-edged sword model that explores the positive and negative impacts of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers on the behavior of observers was constructed in the present study. The empirical results demonstrated that the influences of proactive behaviors (ie, service-oriented OCB) on observers can be either positive or negative, depending on the observers’ attribution of the behavior. By introducing the logic of dialectics into the research of service-oriented OCB, the present study provides a more complete and dialectical theoretical perspective for the relevant literature from the observer-centric perspective.

Third, this research uncovered new behavioral factors that affect the service-oriented OCB of employees. Existing relevant research has rarely considered how the service-oriented OCB of employees is affected by factors related to their coworkers. As stated in previous studies, the impacts of coworkers and the relationships between coworkers and observers on OCB must be considered, as OCB is likely shaped by social and relationship factors.98,99 Unfortunately, empirical research in this area is relatively lacking. The existing literature on the antecedent variables of service-oriented OCB has mainly focused on climate- and supervisor-related variables. Furthermore, the present study enriches the existing literature from the perspective of observers. It was found that the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may also inhibit or promote the service-oriented OCB of observers by dual cognitive pathways (hypocrisy perception vs serving self-efficacy). By identifying new factors that promote and inhibit the service-oriented OCB of employees, the present study further expands the existing literature in the field of service-oriented OCB.

Finally, a dual-pathway framework (hypocrisy perception vs serving self-efficacy) via which service-oriented OCB contagion (vs non-contagion) occurs was identified. It was determined that as the cognitive paths of employees differ, their corresponding behavioral responses will also be different. The hypocrisy mechanism focuses on the willingness of employees to engage in service-oriented OCB, which is necessary to satisfy the proactive nature of service-oriented OCB.55 When employees feel that their coworkers or supervisors are hypocritical, they usually feel uncomfortable, which may inhibit them from implementing OCB.50 The self-efficacy mechanism focuses on the confidence of employees in engaging in service-oriented OCB.71 Moreover, it was further examined why employees can have two different reactions to the certain behavior of a coworker. Drawing on attribution theory, the causal inferences of individuals about past events will affect their own attitudes about and motivation toward future events, and they will adjust their corresponding behavioral response according to the social environment.26,27 Therefore, it is suggested that the attributions (self-serving attribution) of individuals determine the dual cognitive pathways. Specifically, when observers have a high level of self-serving attributions about such positive behaviors, they tend to have hypocrisy perceptions, which will further inhibit their willingness to implement service-oriented OCB. In brief, the present study provides initial evidence that the hypocrisy and serving self-efficacy perceptions of observers are the pathways that separately explain the contagion and non-contagion processes of service-oriented OCB, which provides a deeper understanding of this proactive workplace behavior.

Practical Implications

In addition to the theoretical implications, the present study also has the following implications for the daily management of the hospitality industry.

Service-oriented OCB is widely encouraged in the hospitality industry due to its role in improving enterprise-customer relationships, service performance, etc. However, not all employees are willing to engage in this kind of proactive behavior; on the contrary, many employees implement counterproductive work behaviors.100 Therefore, an in-depth study was conducted on differences in behavioral choices. This research has revealed a very important situation, ie, in a workplace in which the service-oriented OCB of employees is encouraged, blindly asking employees to engage in OCB may have counterproductive effects. On the contrary, managers can refer to the contagion and non-contagion mechanisms proposed in the present study to propose corresponding measures.

First, according to the non-contagion mechanism, the hypocrisy perception interrupts mutual trust between employees. Therefore, managers should promote team building and enhance the mutual trust among employees, which will help dispel employees’ suspicions about the behaviors of their coworkers and promote their improved involvement in work. Second, according to the contagion mechanism, another pathway proposed in the present study, namely self-efficacy, is the key factor that may drive the contagion of service-oriented OCB among employees. Therefore, managers should regularly organize skills training to enhance the confidence of employees in implementing OCB. On the other hand, for those employees who wish to actively contribute to the organization but have no way of starting, the proposed contagion path model also provides a certain reference. These employees can first observe the behaviors of their coworkers, which will help cultivate their confidence in the ability to implement service-oriented OCB. This belief will further promote the implementation of service-oriented OCB.

Moreover, it was further explored why the same employee facing the same incident will have two diametrically opposite cognitive mechanisms. It was found that the attributions of employees determine the dual pathways. Therefore, managers should occasionally conduct moral education and shape the vision of all employees to work hard. In addition, it is necessary to disseminate the benefits of service-oriented OCB to employees, as this will help deepen employees’ awareness of these behaviors. Via these mechanisms, observers will greatly reduce the self-serving attributions of their coworkers’ behavior; this will block the non-contagion mechanism and enhance the contagion mechanism, thereby ultimately promoting the service-oriented OCB of the entire team.

Limitations and Future Research

Consistent with all studies, this article still has the following limitations:

First, the samples for this study were collected from seven large hotels in central and southwestern China. Future studies can collect data from other service-related industries and examine our theoretical model again, which will help verify the universality of our model. At the same time, as mentioned above, our field survey was conducted in China, where the traditional cultural background is different from Western countries. Studies have shown that cultural elements play a key role in the employee OCB’s decision-making process.101 Therefore, it is necessary for the following research to collect samples from countries with other cultural backgrounds and compare the empirical results with this article to analyze the reasons for the differences.

Second, we focused on observers’ behavioral responses to coworkers’ service-oriented OCB. During the survey process, the participants were asked to report their perceptions of the core constructs such as service-oriented OCB, hypocrisy perception, serving self-efficacy and self-serving attribution. Therefore, the variables were all reported by a single source, that is, the observers, which may lead to the common method variance.102 In order to circumvent this problem, a time-lag survey was conducted, and our common method variance met the requirements as well. Future research can try to collect data from multiple sources through sophisticated experiments (such as both coworkers and observers) and use multi-level regression (such as hierarchical linear regression) or random coefficient method to verify our theoretical model again, which may help to improve the research results’ robustness.

Third, present study identified a dual-pathways framework (hypocrisy perception vs serving self-efficacy) through which service-oriented OCB contagion (vs non-contagion) occurs, which constitutes a great complement and enrichment to the existing literatures. However, the other mechanisms have not been considered. Existing literatures on the antecedent variables of service-oriented OCB mainly drawing on social exchange theory, justice theory, social comparison theory, and the job demand-resource model etc. examined the mediating role of justice climate, perceived LMX difference, and depersonalization etc.6,61,95,103 Therefore, it is of great importance for future research to examine the internal mechanism among service-oriented OCB contagion (vs non-contagion) effects, which is more through the present study’s dual-pathways mechanism than the justice, LMX, and other mechanisms mentioned above. Future research can further develop our model and attribution theory by controlling the above alternative mechanisms.

Fourth, future research can further explore the other outcomes of service-oriented OCB. Drawing on attribution theory, this study takes observers’ dual-pathways cognitions (hypocrisy perception and serving self-efficacy) as the mechanism to the double-edged sword effect of coworkers’ service-oriented OCB. However, in addition to attribution perspective, there are still many mechanisms that need to be further examined. For example, from the perspective of conservation of resource, future research can test the loss and acquisition of observers’ own resources after observing coworkers’ service-oriented OCB and their next behavioral decision.

Conclusion

Drawing on attribution theory, it was found that witnessing the service-oriented OCB of coworkers may cause different behavioral responses of observers (ie, promoting vs inhibiting their own service-oriented OCB) via two distinct attribution pathways (serving self-efficacy vs hypocrisy perception); this depends on the self-serving attribution of observers to their coworkers’ behaviors. Specifically, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers will interact to influence the hypocrisy perception of the observers. Thus, the relationship between the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the hypocrisy perception of observers will be stronger and positive when the self-serving attribution of the observers is higher, and will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is lower. Hypocrisy perceptions of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers mediate the relationship between the interactive effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers regarding service-oriented OCB. Furthermore, the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the self-serving attribution of observers will interact to influence the serving self-efficacy of the observers. Thus, the relationship between the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and the serving self-efficacy of observers will be stronger and positive when the self-serving attribution of the observers is low, and will be weaker when the self-serving attribution is lower. The serving self-efficacy of observers mediates the relationship between the interactive effect of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers and self-serving attribution on the service-oriented OCB of observers. Data from seven hotels in central and southwestern China support the proposed theoretical model. By integrating the proposed double-edged sword model of the service-oriented OCB of coworkers, the proposed study makes both theoretical and practical contributions to the field.

Data Sharing Statement

Data supporting the findings presented in the current study will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Statement

Our study did not involve human clinical trials or animal experiments. Meanwhile, current paper did not involve any sensitive topics that may make the participants feel uncomfortable. No deception or concealment of participant information. Based on the above reasons, the research is deemed to meet the institutional requirements and is therefore exempt from ethical recognition. All participants were informed of the research process and provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The above investigation process has been approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the School of Business, Sichuan University.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [72102170; 72172107] and Independent Research Project of Wuhan University [2021XWZY009].

Disclosure

All the authors declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ma E, Qu H. Social exchanges as motivators of hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: the proposition and application of a new three-dimensional framework. Int J Hosp Manag. 2011;30(3):680–688. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.12.003

2. Feng CL, Ma RZ, Jiang L. The impact of service innovation on firm performance: a meta-analysis. J Serv Manag. 2021;32(3):289–314. doi:10.1108/JOSM-03-2019-0089

3. Bettencourt L, Brown S. Contact employees: relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. J Retail. 1997;73:39–61. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90014-2

4. Hur WM, Shin Y, Moon TW. Linking motivation, emotional labor, and service performance from a self-determination perspective. J Serv Res. 2020;1094670520975204. doi:10.1177/1094670520975204

5. Chen W-J. The model of service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior among international tourist hotels. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2016;29:24–32. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.05.002

6. Kloutsiniotis PV, Mihail DM. The effects of high performance work systems in employees’ service-oriented OCB. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;90:102610. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102610

7. Fu H, Li Y, Duan Y. Does employee-perceived reputation contribute to citizenship behavior? Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2014;26(4):593–609. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-02-2013-0082

8. Liang YW. The relationships among work values, burnout, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2012;24(2):251–268. doi:10.1108/09596111211206169

9. Karatepe OM, Yavas U, Babakus E. The effects of customer orientation and job resources on frontline employees’ job outcomes. Serv Mark Q. 2007;29(1):61–79. doi:10.1300/J396v29n01_04

10. Chen C-T, Hu HHS, King B. Shaping the organizational citizenship behavior or workplace deviance: key determining factors in the hospitality workforce. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2018;35:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.01.003

11. Tang YY, Tsaur SH. Supervisory support climate and service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in hospitality. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2016;28(10):2331–2349. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-09-2014-0432

12. Tuan LT, Rowley C, Masli E, Le V, Nhi LTP. Nurturing service -oriented organizational citizenship behavior among tourism employees through leader humility. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2021;46:456–467. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.02.001

13. Podsakoff NP, Whiting SW, Podsakoff PM, Blume BD. Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(1):122–141. doi:10.1037/a0013079

14. Raub S. Does bureaucracy kill individual initiative? The impact of structure on organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry. Int J Hosp Manag. 2008;27(2):179–186. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.07.018

15. Zhou X, Fan L, Cheng C, Fan Y. When and why do good people not do good deeds? Third-party observers’ unfavorable reactions to negative workplace gossip. J Bus Ethics. 2021;171:599–617.

16. Qin X, Chen C, Yam KC, Huang M, Ju D. The double-edged sword of leader humility: investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(7):693–712. doi:10.1037/apl0000456

17. Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol Rev. 1985;92(4):548–573. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

18. Kelley H. Attribution theory in social psychology. In: Levine D, editor. Nebraska Symposium of Motivation. Vol. 14. Chicago: University of Nebraska Press; 1967:192–238.

19. Weiner B. A theory of motivation for some classroom experience. J Educ Psychol. 1979;71(1):3–25. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.3

20. Weiner B. Reflections on the history of attribution theory and research: people, personalities, publications, problems. Soc Psychol. 2008;39(3):151–156. doi:10.1027/1864-9335.39.3.151

21. Banki S. Is a good deed constructive regardless of intent? Organization citizenship behavior, motive, and group outcomes. Small Group Res. 2010;41(3):354–375. doi:10.1177/1046496410364065

22. Bowler WM, Halbesleben JRB, Paul JRB. If you’re close with the leader, you must be a brownnose: the role of leader–member relationships in follower, leader, and coworker attributions of organizational citizenship behavior motives. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2010;20(4):309–316. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.04.001

23. Allen T, Rush M. The effects of organizational citizenship behavior on performance judgments: a field study and a laboratory experiment. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(2):247–260. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.247

24. Feldman J. Beyond attribution theory: cognitive processes in performance appraisal. J Appl Psychol. 1981;66(2):127–148. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.66.2.127

25. Heider F. Perceiving the other person. In: Tagiuri R, Petrullo L, editors. Person Perception and Interpersonal Behavior. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1958:22–26.

26. Martinko M, Harvey P, Douglas S. The role, function, and contribution of attribution theory to leadership: a review. Leadership Q. 2007;18(6):561–585. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.004

27. Weiner B, Kukla A. An attributional analysis of achievement motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1970;15(1):1–20. doi:10.1037/h0029211

28. Klein J, Dawar N. Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in product harm crisis. Int J Res Mark. 2004;21(3):203–217. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.003

29. Snell R, Wong Y. Differentiating good soldiers from good actors. J Manag Stud. 2007;44:883–909. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00699.x

30. Donai M, Johns G, Raja U. Good soldier or good actor? Supervisor accuracy in distinguishing between selfless and self-serving OCB motives. J Bus Psychol. 2016;31:23–32.

31. De Stobbeleir KEM, Ashford S, Sully de Luque M. Proactivity with image in mind: how employee and manager characteristics affect evaluations of proactive behaviours. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;83(2):347–369. doi:10.1348/096317909X479529

32. Bolino MC. Citizenship and impression management: good soldiers or good actors? Acad Manage Rev. 1999;24(1):82–98. doi:10.2307/259038

33. Impression management: a literature review and two-component model [press release]. US: American Psychological Association; 1990.

34. Eastman KK. In the eyes of the beholder: an attributional approach to ingratiation and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad Manage J. 1994;37(5):1379–1391.

35. Grant A, Parker S, Collins C. Getting credit for proactive behavior: supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Pers Psychol. 2009;62(1):31–55. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01128.x

36. Wong P, Weiner B. Why people ask “Why” questions and the heuristics of attributional search. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;40(4):650–663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.40.4.650

37. Bettencourt L, Gwinner K, Meuter M. A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(1):29–41. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.29

38. Shukla A. Soldier or actor? Int J Organ Anal. 2019;27(1):94–108. doi:10.1108/IJOA-08-2017-1214

39. Donia MBL, Johns G, Raja U, Khalil Ben Ayed A. Getting credit for OCBs: potential costs of being a good actor vs. a good soldier. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(2):188–203. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2017.1418328

40. Lanaj K, Johnson RE, Lee SM. Benefits of transformational behaviors for leaders: a daily investigation of leader behaviors and need fulfillment. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(2):237–251. doi:10.1037/apl0000052

41. Johnson RE, Venus M, Lanaj K, Mao C, Chang C-H. Leader identity as an antecedent of the frequency and consistency of transformational, consideration, and abusive leadership behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(6):1262–1272. doi:10.1037/a0029043

42. Bolino MC, Klotz AC, Turnley WH, Harvey J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(4):542–559. doi:10.1002/job.1847

43. Cheung M, Peng Z, Wong C-S. Supervisor attribution of subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior motives. J Manag Psychol. 2014;29(8):922–937. doi:10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0338

44. Parke MR, Tangirala S, Hussain I. Creating organizational citizens: how and when supervisor- versus peer-led role interventions change organizational citizenship behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106:1714–1733.

45. Moeran B. Tricks of the trade: the performance and interpretation of authenticity. J Manag Stud. 2005;42(5):901–922. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00526.x

46. Meindl JR. On leadership: an alternative to conventional wisdom. Res Organ Behav. 1990;12:159–203.

47. Vonk R. Self-serving interpretations of flattery: why ingratiation works. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(4):515–526. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.515

48. Takaku S. Reducing road rage: an application of the dissonance-attribution model of interpersonal forgiveness 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36(10):2362–2378. doi:10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00107.x

49. Karadenizova Z, Dahle K-P. Analyze This! Thematic analysis: hostility, attribution of intent, and interpersonal perception bias. J Interpers Violence. 2017;36(3–4):1068–1091. doi:10.1177/0886260517739890

50. Greenbaum R, Mawritz M, Piccolo R. When leaders fail to “Walk the Talk”. J Manage. 2012;41(3):929–956. doi:10.1177/0149206312442386

51. Cha SE, Edmondson AC. When values backfire: leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values-driven organization. Leadership Q. 2006;17(1):57–78. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.10.006

52. Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(2):364–374. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

53. Moore C, Detert J, Trevino L, Baker V, Mayer D. Why employees do bad things: moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Pers Psychol. 2012;65(1):1–48. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

54. Kish-Gephart J, Detert J, Treviño LK, Baker V, Martin S. Situational moral disengagement: can the effects of self-interest be mitigated? J Bus Ethics. 2014;125(2):267–285. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1909-6

55. Sun L-Y, Aryee S, Law K. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: a relational perspective. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(3):558–577. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

56. Bandura A, Freeman WH, Lightsey R. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. J Cogn Psychother. 1997;13(2):158–166. doi:10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

57. Wu J, Liden RC, Liao C, Wayne SJ. Does manager servant leadership lead to follower serving behaviors? It depends on follower self-interest. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(1):152–167. doi:10.1037/apl0000500

58. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

59. Judge T, Bono J. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(1):80–92. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

60. Otaye-Ebede L, Shaffakat S, Foster S. A multilevel model examining the relationships between workplace spirituality, ethical climate and outcomes: a social cognitive theory perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2020;166(3):611–626. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04133-8

61. Tang T-W, Tang -Y-Y. Promoting service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors in hotels: the role of high-performance human resource practices and organizational social climates. Int J Hosp Manag. 2012;31(3):885–895. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.007

62. Tung VWS, Chen PJ, Schuckert M. Managing customer citizenship behaviour: the moderating roles of employee responsiveness and organizational reassurance. Tour Manag. 2017;59:23–35. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.010

63. Hoover JD, Giambatista RC, Belkin LY. Eyes on, hands on: vicarious observational learning as an enhancement of direct experience. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2012;11(4):591–608. doi:10.5465/amle.2010.0102

64. Myers CG. Coactive vicarious learning: toward a relational theory of vicarious learning in organizations. Acad Manage Rev. 2017;43(4):610–634. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0202

65. Zimmerman BJ, Bell JA. “Observer verbalization and abstraction in vicarious rule learning, generalization, and retention”: Erratum. Dev Psychol. 1973;8(3):340. doi:10.1037/h0020254

66. Greve HR. Learning theory: the pandemic research challenge. J Manag Stud. 2020;57(8):1759–1762. doi:10.1111/joms.12631

67. Zhang Z, Liang Q, Li J. Understanding managerial response to employee voice: a social persuasion perspective. Int J Manpow. 2020;41(3):273–288. doi:10.1108/IJM-05-2018-0156

68. Spector PE, Fox S. Theorizing about the deviant citizen: an attributional explanation of the interplay of organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2010;20(2):132–143. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.06.002

69. De Dreu C, Nauta A. Self-interest and other-orientation in organizational behavior: implications for job performance, prosocial behavior, and personal initiative. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(4):913–926. doi:10.1037/a0014494

70. Parker SK, Bindl UK, Strauss K. Making things happen: a model of proactive motivation. J Manage. 2010;36(4):827–856. doi:10.1177/0149206310363732

71. Liden R, Wayne S, Zhao H, Henderson D. Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadership Q. 2008;19(2):161–177. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

72. Ng TWH, Lucianetti L, Hsu DY, Yim FHK, Sorensen KL. You speak, I speak: the social-cognitive mechanisms of voice contagion. J Manag Stud. 2021;58(6):1569–1608. doi:10.1111/joms.12698

73. Schwarz N, Clore G. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: informative and directive functions of affective states. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45(3):513–523. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.513

74. Gremler DD. The critical incident technique in service research. J Serv Res. 2004;7(1):65–89. doi:10.1177/1094670504266138

75. Viergever RF. The critical incident technique: method or methodology? Qual Health Res. 2019;29(7):1065–1079. doi:10.1177/1049732318813112

76. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

77. Dineen BR, Lewicki RJ, Tomlinson EC. Supervisory guidance and behavioral integrity: relationships with employee citizenship and deviant behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(3):622–635. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.622

78. Rioux SM, Penner LA. The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: a motivational analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(6):1306–1314. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1306

79. Jia Y, Yan J, Liu T, Huang J. How does internal and external CSR affect employees’ work engagement? Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms and boundary conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2476. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142476

80. Kowal J, Keplinger A, Mäkiö J. Organizational citizenship behavior of IT professionals: lessons from Poland and Germany. Inf Technol Dev. 2019;25(2):227–249. doi:10.1080/02681102.2018.1508402

81. Kowal J, Keplinger A. Characteristics of human potentiality and organizational behavior among IT users in Poland. An exploratory study. Ekonometria Econometrics. 2015;3:49.

82. Kowal J, Gurba A. Mobbing and burnout in emerging knowledge economies: an exploratory study in Poland.

83. Jia Y, Wang T, Xiao K, Guo C. How to reduce opportunism through contractual governance in the cross-cultural supply chain context: evidence from Chinese exporters. Ind Mark Manag. 2020;91:323–337. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.09.014

84. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

85. Tehseen S, Ramayah T, Sajilan S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: a review of available methods. J Manage Sci. 2017;4(2):142–168. doi:10.20547/jms.2014.1704202

86. Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage. 1986;12(4):531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408

87. Keplinger A, Kowal J, Mäkiö J Gender and organizational citizenship behavior of information technology users in Poland and Germany.

88. Drasgow F, Levine MV, Tsien S, Williams B, Mead AD. Fitting polytomous item response theory models to multiple-choice tests. Appl Psychol Meas. 1995;19(2):143–166. doi:10.1177/014662169501900203

89. Kowal J, Roztocki N. Do organizational ethics improve IT job satisfaction in the visegrád group countries? Insights from Poland. J Glob Inf Technol Manag. 2015;18(2):127–145. doi:10.1080/1097198X.2015.1052687

90. Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

91. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

92. Kowal J, Paliwoda-Pękosz G. ICT for global competitiveness and economic growth in emerging economies: economic, cultural, and social innovations for human capital in transition economies. Inf Syst Manag. 2017;34(4):304–307. doi:10.1080/10580530.2017.1366215

93. Hayes A. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

94. Spiller SA, Fitzsimons GJ, Lynch JG, Mcclelland GH. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: simple effects tests in moderated regression. J Market Res. 2013;50(2):277–288. doi:10.1509/jmr.12.0420

95. Kang J, Jang J. Fostering service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through reducing role stressors. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019;31(9):3567–3582. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-12-2018-1018

96. Breidenthal AP, Liu D, Bai Y, Mao Y. The dark side of creativity: coworker envy and ostracism as a response to employee creativity. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;161:242–254. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.08.001

97. Mao Y, He J, Yang D. The dark sides of engaging in creative processes: coworker envy, workplace ostracism, and incivility. Asia Pac J Manag. 2021;38:1261–1281.

98. Scott KL, Zagenczyk TJ, Li S, Gardner WL, Cogliser C, Laverie D. Social network ties and organizational citizenship behavior: evidence of a curvilinear relationship. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(6):752–763.

99. Morrison E. Employee voice and silence. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:173–197. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

100. Dalal RS. A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(6):1241–1255. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

101. Kwantes CT, Karam CM, Kuo BCH, Towson S. Culture’s influence on the perception of OCB as in-role or extra-role. Int J Intercult Relat. 2008;32(3):229–243. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.007

102. Podsakoff P, MacKenzie S, Podsakoff N. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2010;63(1):539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

103. Chiniara M, Bentein K. The servant leadership advantage: when perceiving low differentiation in leader-member relationship quality influences team cohesion, team task performance and service OCB. Leadership Q. 2018;29(2):333–345. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.002

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.