Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 13

The Iranian Protocol of Group Reminiscence and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Institutionalized Older People

Authors Kousha A , Sayedi A, Rezakhani Moghaddam H , Matlabi H

Received 21 June 2020

Accepted for publication 7 September 2020

Published 28 September 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 1027—1034

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S263421

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Ahmad Kousha,1 Adnan Sayedi,1 Hamed Rezakhani Moghaddam,2 Hossein Matlabi1

1Department of Health Education and Promotion, Faculty of Health Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; 2Department of Public Health, Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences, Khalkhal, Iran

Correspondence: Hossein Matlabi

Faculty of Health Sciences, Attare Neishabouri St, Tabriz 5165665811, Iran

Tel +984133357583

Fax +984133344731

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Reminiscence has a positive role in improving memory performance. It may increase the attention of the older adults to themselves, helping them to cope with the crises and the process of aging. We aimed to investigate the impacts of memory recalling, sharing life experiences and stories confidently from the past on promoting numerous domains of quality of life (QoL), among institutionalized older people in the Ilam province of Iran.

Methods: The study was carried out, using a quasi-experimental approach (a pre- and post-one group design). The statistical population consisted of all older people who were institutionalized in nursing homes. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 43 potential participants were recruited, and the status of QoL was assessed, using the Iranian short-form health survey (SF-36) and face to face interviews. Then, eight sessions were designed and implemented. The participants expressed their memories such as bitter and sweet memories at various periods of life, and finally, the QoL of the participants was re-evaluated according to the same questionnaire, three months after the intervention.

Results: There was a significant difference between the scores of pre- and post-intervention in most of the sub-scales of QoL, including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health and emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, and general health.

Conclusion: Reminiscence may, in certain circumstances, be an effective care option for people living in long-term care with the potential to impact positively on the QoL of residents.

Keywords: reminiscence, quality of life, older people, nursing homes, Ilam

Introduction

Improving living conditions and increasing life expectancy have led to the aging phenomenon. The implications of an aging population are one of the most important economic, social and health challenges for health care providers, family members as well as societies.1,2 At present, the older adults have the highest population growth rate, in comparison with the other groups.3 These changes are a revolutionary sign in the demographic dimension of communities that take strict attention to policy-makers, worldwide.4 World statistics show that the population of this age group will double until 2050. The rate of the aging population in developing countries such as Iran is rising as the population structure changes.5 Moreover, changes in disease patterns have increased chronic difficulties among older people, and consequently led to improved attention to the concepts of health and quality of life (QoL), in the past decade.6–8 From the perspective of the World Health Organization, this represents an individual’s perception of the status of life based on culture, goals, value system, standards and personal interests.9

Furthermore, one thing to keep in mind is how life is spent. Having a proper social relationship, a beneficial role in society, the opportunity to make fun, being healthy, and financial independence, all together determine the status of QoL.10 According to the special needs of older people, their QoL can be easily threatened.11 Nowadays, improving the QoL among institutionalized older people is one of the important aspects of nursing care standards.12

Reminiscence may improve cognitive health (the ability to clearly think, learn, and remember) by boosting memory and enhancing the effects of other treatments.13 It covers also a situation that is often used for the older adults based on remembering events, feelings and thoughts of the past, in order to create and facilitate the feeling of pleasure, and to enhance the QoL or to adapt to current situations.14 Most studies recommended that it can be used in nursing homes, different schemes and private houses. Reminiscence may have a positive role in improving the QoL, memory performance, awareness and health status as applied as a psychological treatment and, in fact, a kind of past-calling and can be smart for older persons.14,15 This attraction can have three reasons as follows: first, as a part of daily activity, the participants do not have to learn new words and form an initial form of human experiences that are semantically motivated; second, many older people are returning to the past through reminders, as remembering these memories may help people to get more balance in their lives. Finally, because of the challenges faced by their age-class drawbacks in social relations, the residents share experiences, feelings and memories in small groups.16

Several studies have used reminiscence for improving QoL among older people.17 The literature suggested that structured reminiscence may be beneficial in treating depression. In examining the psychological benefits of the program, a study confirmed that two components of subjective well-being, including life satisfaction and happiness, have been increased by improving social skills and emotional supports.18 Another study concluded that reminiscence was associated with positive emotions among older people.19 Due to the feasibility of this technique and different findings concerning its effect, there is a need for further research on reminiscence to improve the well-being of older adults.

Methods

Setting

All institutionalized residents aged 60 years and over, living in two nursing home centers situated in the Ilam province of Iran, had an equal chance to participate in the study (n=60: Ilam=39 and Eyvan = 21). A nursing home is used in many countries to refer to the centers, where in addition to the housing, support and nursing services are also delivered for older people who cannot live independently in their own houses. In nursing homes, the short-term services are provided to those who require nursing care, assistance in personal activities, and mobility.20

Study Design and Data Collection

The study was carried out by using a quasi-experimental approach (a pre- and post-one group design) and a non-probability sampling technique during 2018–2019. A one-group pre-test–post-test design is a type of research that is most often used by behavioral researchers to determine the effect of a treatment or intervention on a given sample. The health status of the participants was examined based on medical records and applying for the Iranian Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). The MMSE consists of 11 questions examining orientation, memory, calculation, attention, comprehension, and visual-spatial function. The score ranges from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating better cognitive functioning.4

Older people were considered ineligible, if they had multiple chronic difficulties or cognitive impairment (a score of 23 or less), or were too frail to undertake the survey. Out of 60 older people in nursing homes, 17 did not have the desired characteristics. The status of the overall score of health-related QoL was assessed, using the Iranian short-form health survey (SF-36),15 and face to face interviews in a private area. Then, eight local sessions (Table 1) were designed and implemented. The institutionalized participants expressed their memories such as bitter and sweet memories at different periods of life and finally, the QoL of the participants was re-evaluated according to the same questionnaire, three months after the intervention. The study instrument and questionnaire were valid and reliable.

|

Table 1 Iranian Protocol for Structured Reminiscence |

The Reminiscence Program and Protocol

Based on an overview of qualitative and quantitative research on group reminiscence, Stinson (2009) offered a suggested protocol for group intervention.14 The original protocol involves 12 sessions, which has been validated among older Iranian people.15 The Iranian protocol consists of eight topics as follows:4,13,15

- Understanding the aims, team process and interesting topics;

- Expression of childhood memories, adolescence, and later life;

- Family history, life process and marriage;

- Life in the city and the village and its bitter and sweet memories;

- Expression of work memories and experiences, job positions and successes;

- Benevolence, charity, and worship;

- Memories of wars: front-line, the displacement, and the events of that era;

- Free discussions.

Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, scheme managers selected, organized, and facilitated reminiscence groups for older people. All participants attended an eight-weekly session of the reminiscence program, in which clinical psychologist acted as a facilitator to encourage the participants to share, teach and fabricate a personalized life-story based on the chosen reminiscence topics, using the local language (Southern Kurdish). The reminiscence program was structured in such a way that focuses on three functions including promoting interaction, teach, and inform and reinforcing self-image. During the sessions, the facilitator used various techniques as cognitive support to prompt the participants’ recall of past memories and to provide them structured opportunities to talk and share personal wisdom and past experiences related to the topics with other participants. They also supported the participants to fabricate a personalized life-story book based on the chosen reminiscence topics. Each session lasted for about 90 minutes.

Data Analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine if a data set was well modeled by a normal distribution (p > 0.05). Moreover, paired t-tests were used to test if the means of two paired measurements, such as pre-test/post-test scores, are significantly different. The significance level was considered 0.05.

Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (approval number.IR.TBZMED.REC.1397.021). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures performed in this study were following the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee.

Results

In this section, the characteristics of the 43 participants including gender, age, marital status and educational level are described. More than half of the respondents (60%) were women, as well as 79% of them aged 60–75 years old. Furthermore, approximately two-thirds of the participants were widowed and 88% were illiterate.

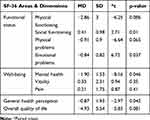

The distributions of SF-36-dimension scores, including physical and social functioning, role limitations (physical and emotional problems), mental health, vitality, pain, and general health perception are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 demonstrates the mean scores of the outcome measures before and after the intervention. Significant pre- and post-program differences were found for the most SF-36 areas and dimensions. No statistically significant changes were found for social functioning, vitality, and pain.

|

Table 2 The Distribution of SF-36 Areas and Dimensions (n=43) |

|

Table 3 The Association of SF-36 Dimensions and Reminiscence (n=43) |

As illustrated in Table 3, the results of paired t-tests indicated that the QoL scores have meaningfully increased after the intervention (p=0.081).

Discussion

The participants reported gains in the most SF-36 areas and dimensions, including physical functioning, role limitations (physical and emotional problems), emotional well-being and general health, as well as overall QoL scores. As hypothesized, the mean score of physical function was different before and after the intervention. This finding was consistent with the results of the other studies.18,21–24 Older people experience a better inner feeling by expressing and reviewing their past memories, spent in a busy period. Moreover, they may act more energetically by discharging their emotions while reminiscing.22,23 On the contrary, participation in group reminiscence sessions could not significantly increase physical functions among the older adults, living in the community.22–25 This discrepancy can be due to differences in research settings.

The structured group reminiscence improved the social functions of the participants (p=0.01). The determining factors of social functioning and psychological distress are not yet fully known among older people.18,19 When older people become more and more disabled and lose their capacity to participate in social activities, they may replace these activities with tasks that do not require much physical strength such as reminiscence.26 In fact, group reminiscence maintains the identity of older people by keeping them in a symbolic interactive framework.15–18

The results of the paired t-tests revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of role limitations (physical problems) before and after the intervention. Consistent results were reported in other literature.18,21–23 For older adults, leisure activities are a great way to stay healthy and fit.24 It has been repeatedly shown that staying active during the last period of life is associated with less disease and lower mortality rate as it promotes health.23

Before and after the intervention, the mean score of role limitations (emotional problems) was statistically significant. The findings of most studies were similar to the results of the present study.21,22,24 To explain this, it can be stated that the inevitable physical and mental weakness during life may make older people very vulnerable. Moreover, the residents of nursing homes have different unanswered needs, which often lead to increased behavioral and mental difficulties. Unfortunately, many of the symptoms of mental illness, being usually normal in the aging process either are ignored or underestimated, which will eventually give rise to numerous problems in these periods.14,18,23

Furthermore, the mean score of vitality before and after the intervention was 11.99 and 11.66 (p=0.35), respectively. This finding is inconsistent with the results of many studies, which might be caused by differences in gender and marital status of the participants.25–27 Factors such as resolving long-standing problems, increasing tolerance to conflicts, relieving feelings of guilt, fear and strengthening self-esteem, creativity, open-mindedness and acceptance can affect feelings of vitality. It can be said that factors such as solving long-standing problems, increasing conflict tolerance, reducing unhealthy guilt, strengthening self-esteem, creativity, generosity and acceptance may improve the feeling of vitality among older people.14,16

Regarding the status of mental health, the comparison of the scores revealed that there was a meaningful difference before and after the intervention, which was consistent with the results of other studies.28,29 Reminiscence plays a helpful role in supporting mental health and may have long-term effects on improving the QoL.15,26 The theoretical framework of reminiscence therapy is derived from Erikson’s theory of ego development. Erikson divided life span into eight stages. In his theory, Erikson believed people would experience a main crisis or conflict in each stage, which served as a turning point in development and needed to be solved.30 In the theory, reminiscence plays a key role in the end-stages of life and acts as a potential in resolving psychological problems by helping the older adults to regain their integrity. When older people living in nursing homes attend a reminiscence session, they will get an opportunity to make new friends, deepen their friendships, and be able to communicate with others. In addition, the group leads to a reduction in the feeling of distance in the new situation through interpersonal relationships and the provision of social support by others.14,29,30

The pain intensities of the participants did not decrease after the structured group reminiscence among institutionalized older people (p=0.41). This result was inconsistent with many reports.24,31 To explain this finding, it can be said that most of the participants (88%) were illiterate and had to do manual and physical works such as agricultural and animal husbandry occupations to earn incomes, and therefore the physical chronic pain continues to increase with age. To reduce this contradictory issue, it might be better to provide suitable conditions and facilities such as non-invasive pain relief techniques and rational coping in nursing home centers.

As hypothesized, general health perception has increased over time (p=0.042). Tarugu et al considered group reminiscence to improve the general health of older adults, living in nursing homes and believed that this method would recover the physical and social functions.31 To explain this finding, reminiscence is usually a conceptual method for examining and reviewing life events and a psychological process, where past events and occasions are discussed.14,26,30

Finally, the comparison of the overall scores of health-related QoL indicated that the evidence-based protocol for an 8-week group intervention could suggest beneficial values for participants. This finding concurs with previous studies.32–34 This can partially explain that reminiscence may extend interpersonal communications, provide an opportunity to express positive and negative feelings towards the past, reconcile with the present, improve the career and family relationships, focus on high-quality interactions, and provide a supportive and relaxing environment.27–31,35,36

Limitations

This was a one-group pre-post design, with no control group, and the pre-intervention scores acting as the baseline control. Although most of the literature has explored the positive effects of reminiscence on older people such as social networks, psychological well-being and social status, the possibilities of negative consequences have been neglected. Finally, while the current research has contributed to increasing the understanding of the meaning of general health ratings, little or nothing is known about the clinical significance of these scores.

Conclusion

Structured group reminiscence has implications on improving the well-being of older persons. Discussing past events allows group members to become more familiar with each other, which increases the growth of group solidarity and received support; it also provides a warm and compassionate environment to feel free to reminisce. The structured group reminiscence helps the older adults to gain positive self-esteem by increasing self-confidence, emotional well-being, and a sense of satisfaction by reminding and rebuilding experiences.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the Deputy of Research and Technology for valuable supports. We are also most grateful for the assistance provided by the facilitators and participants.

Author Contributions

As scholars, we attempted to do high-quality research that advance science. We correspondingly used an appropriate research methodology. We also have read and reviewed the manuscript carefully several times, received feedback from our colleagues, and identified the aims and scope of the journals in our target research area. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas. Moreover, all authors drafted or written, or substantially revised or critically reviewed the article. They agreed on the journal where the article will be submitted, and reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission, during revision, and approved the final manuscript. All authors agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Baars J, Dannefer D, Phillipson C, Walker A. Aging, Globalization and Inequality: The New Critical Gerontology. Routledge; 2016.

2. Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, et al. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. McGraw-Hill Education/Medical; 2009.

3. World Health Organization. Good Health Adds Life to Years: Global Brief for World Health Day 2012. World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/whd2012_global_brief/en/.

4. Tajvar M, Grundy E, Fletcher A. Social support and mental health status of older people: a population-based study in Iran-Tehran. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(3):344–353. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1261800

5. World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/.

6. Chen HM, Chen CM. Factors associated with quality of life among older adults with chronic disease in Taiwan. Int J Gerontol. 2017;11(1):12–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijge.2016.07.002

7. Estes RJ. National Quality of Life and Well-Being: 50 Years of Development and Well-Being Challenges and Progress. In: The Social Progress of Nations Revisited, 1970–2020. Vol. 78. Springer, Cham: Social Indicators Research Series; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15907-8_6

8. Tuzikov AR, Zinurova RI, Emelina ED, et al. Global challenges of the 21st century and possible university’s answer. Ekoloji. 2019;107:33–38.

9. THE WHOQOL GROUP. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–558. doi:10.1017/s0033291798006667

10. Bowling A, Gabriel Z. Lay theories of quality of life in older age. Ageing Soc. 2007;27(6):827–848. doi:10.1017/s0144686x07006423

11. van Leeuwen KM, van Loon MS, van Nes FA, et al. What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213263. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213263

12. Miori V, Russo D. Improving life quality for the elderly through the Social Internet of Things (SIoT). Global Int Things Summit. 2017;6:1–6. doi:10.1109/giots.2017.8016215

13. Sheykhi MT. Social security and the elderly people’s pathology in Tehran: a sociological study. Iranian J Ageing. 2008;10:454–461.

14. Stinson CK. Structured group reminiscence: an intervention for older adults. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2009;40(11):521–528. doi:10.3928/00220124-20091023-10

15. Sharif F, Jahanbin I, Amirsadat A, Moghadam MH. Effectiveness of life review therapy on quality of life in the late life at day care centers of Shiraz, Iran: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2018;6:136–145.

16. Gaggioli A, Scaratti C, Morganti L, et al. Effectiveness of group reminiscence for improving wellbeing of institutionalized elderly adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):408. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-408

17. Jones ED, Beck-Little R. The use of reminiscence therapy for the treatment of depression in rural-dwelling older adults. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(3):279–290. doi:10.1080/016128402753543018

18. Cappeliez P, Guindon M, Robitaille A. Functions of reminiscence and emotional regulation among older adults. J Aging Stud. 2008;22(3):266–272. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.06.003

19. Elford H, Wilson F, McKee KJ, Chung MC, Bolton G, Goudie F. Psychosocial benefits of solitary reminiscence writing: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):305–314. doi:10.1080/13607860500131492

20. Ghavarskhar F, Matlabi H, Gharibi F. A systematic review to compare residential care facilities for older people in developed countries: practical implementations for Iran. Cogent Soc Sci. 2018;4(1):1478493. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1478493

21. Stinson CK, Young EA, Kirk E, Walker R. Use of a structured reminiscence protocol to decrease depression in older women. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(8):665–673. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01556.x

22. O’Shea E, Devane D, Cooney A, et al. The impact of reminiscence on the quality of life of residents with dementia in long-stay care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(10):1062–1070. doi:10.1002/gps.4099

23. Hsieh HF, Wang JJ. Effect of reminiscence therapy on depression in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(4):335–345. doi:10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00101-3

24. Poulin V, Carbonneau H, Provencher V, et al. Participation in leisure activities to maintain cognitive health: perceived educational needs of older adults with stroke. Soc Leisure. 2019;42:4–23. doi:10.1080/07053436.2019.1582901

25. Chiang KJ, Chu H, Chang HJ, et al. The effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well‐being, depression, and loneliness among the institutionalized aged. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):380–388. doi:10.1002/gps.2350

26. Taft LB, Nehrke MF. Reminiscence, Life Review, and Ego Integrityin Nursing Home Residents. The Meaning of Reminiscence and Life Review. Routledge; 2019:185–192.

27. Museums Victoria. Reminiscing kits. Available from: https://museumsvictoria.com.au/learning/outreach-program/reminiscing-kits/. Accessed September 16, 2020.

28. Peng XD, Huang CQ, Chen LJ, Lu ZC. Cognitive behavioral therapy and reminiscence techniques for the treatment of depression in the elderly: a systematic review. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(4):975–982. doi:10.1177/147323000903700401

29. MacKinlay E, Trevitt C. Living in aged care: using spiritual reminiscence to enhance meaning in life for those with dementia. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19(6):394–401. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00684.x

30. Chen T, Li H, Li J. The effects of reminiscence therapy on depressive symptoms of Chinese elderly: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):2–6. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-12-189

31. Tarugu J, Pavithra R, Vinothchandar S, et al. Effectiveness of structured group reminiscence therapy in decreasing the feelings of loneliness, depressive symptoms and anxiety among inmates of a residential home for the elderly in Chittoor district. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6(2):847. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190218

32. Siverová J, Bužgová R. The effect of reminiscence therapy on quality of life, attitudes to ageing, and depressive symptoms in institutionalized elderly adults with cognitive impairment: a quasi‐experimental study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(5):1430–1439. doi:10.1111/inm.12442

33. Hsu FY, Yang YP, Lee FP, et al. Effects of group reminiscence therapy on agitated behavior and quality of life in taiwanese older adults with dementia. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;11(57):30–36. doi:10.3928/02793695-20190315-01

34. Bissonnette BA, Barnes MA. Group reminiscence therapy: an effective intervention to improve depression, life satisfaction, and well-being in older adults? Int J Group Psychother. 2019;69(4):460–469. doi:10.1080/00207284.2019.1640610

35. Gil I, Costa P, Parola V, et al. Efficacy of reminiscence in cognition, depressive symptoms and quality of life in institutionalized elderly: a systematic review. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da USP. 2019:53. doi:10.1590/s1980-220x2018007403458

36. Chung JC. An intergenerational reminiscence programme for older adults with early dementia and youth volunteers: values and challenges. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(2):259–264. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00615.x

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.