Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 8

The experiences of women with polycystic ovary syndrome on a very low-calorie diet

Authors Love J, McKenzie J, Nikokavoura EA , Broom J, Rolland C, Johnston K

Received 12 November 2015

Accepted for publication 1 April 2016

Published 21 July 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 299—310

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S100385

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

John G Love,1 John S McKenzie,2 Efsevia A Nikokavoura,3 John Broom,3 Catherine Rolland,3 Kelly L Johnston4,5

1School of Applied Social Studies, Faculty of Health & Social Care, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK; 2Rowett Institute of Health & Nutrition, University of Aberdeen, St Mary’s, Kings College, Aberdeen, UK; 3Centre for Obesity Research, Faculty of Health & Social Care, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK; 4LighterLife, Harlow, Essex, UK; 5Diabetes and Nutritional Sciences Division, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Kings College London, London, UK

Abstract: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is variously reported to affect between 5% and 26% of reproductive age women in the UK and accounts for up to 75% of women attending fertility clinics due to anovulation. The first-line treatment option for overweight/obese women with PCOS is diet and lifestyle interventions. However, optimal dietary guidelines are missing, with very little research having been done in this area. This paper presents the findings from a qualitative study (using semistructured interviews) of ten obese women who had PCOS and who had used LighterLife Total (LLT), a commercial weight loss program which utilizes a very low-calorie diet in conjunction with behavioral change therapy underpinned by group support. We investigated the women’s history of obesity, their experiences of other diets compared with LLT, and the on-going impact that this has had on their lives. Findings show that most women reported greater success using this weight loss program in terms of achieving and maintaining weight loss when compared with other diets. Furthermore, all the women nominated LLT as their model weight loss intervention with only a few modifications.

Keywords: PCOS, obesity, weight loss, diet

Introduction

This paper presents findings from a study of women who suffer from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and who have attempted to lose weight using a very low-calorie diet (VLCD)-based weight loss program, ie, LighterLife Total (LLT). The study sought to describe, in the words of the women themselves, the experience of living with PCOS, their use of other weight loss programs prior to LLT, as well as establishing their views on LLT. The paper also seeks to identify the barriers that the women face while trying to lose weight (comparing the experience of LLT with other weight loss interventions). In conclusion, it will be reported that although all the women recommended LLT as a model weight loss intervention, some would like to see modifications which they suggest may potentially enhance its efficacy for women with PCOS.

Background

PCOS is one of the most common female endocrine disorders, affecting 5%–26% of women of reproductive age in the UK.1–3 There is, however, a lack of consensus over the diagnostic criteria used by physicians, influencing the variability observed in its prevalence. PCOS has been associated not only with a variety of reproductive and skin disorders, but also with an adverse metabolic profile that includes systemic dysfunctions such as insulin resistance with compensatory hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.4,5 In addition, at least half of the women with PCOS are obese.6,7 However, it is still debatable whether heavier women are predisposed to PCOS, or are obese because they have PCOS, or if the differences between women with and without PCOS are due to environmental and lifestyle factors.8

Moreover, chronic disease itself is a risk factor for depressive disorders and decreased quality of life (QOL).9 In addition, many of the PCOS features, such as menstrual irregularities, difficulties in conceiving, and problems with physical appearance (eg, acne, hirsutism, excess weight, body shape, etc), intensify self-dissatisfaction and perceived lower QOL.10–12 This links to a high prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety among PCOS patients,13–15 which in some cases, appears significantly increased when compared with either weight-matched15 or aged-matched10 healthy women.

All these may affect the rate of weight loss; thus, it has been reported that obese women with PCOS face additional barriers in achieving weight loss when compared with healthy women without this condition.16 Herriot et al17 suggested that the barriers to weight loss among healthy obese individuals are summarized into two main categories: lifestyle (free time available, work, family obligations, exercise, etc) and psychological barriers (depression, stress, lack of focus, locus of control, etc). Other characteristics that predict success in weight reduction in overweight and/or obese populations include increased self-esteem, self-efficacy, high levels of motivation, and a small number of previous dieting attempts.18 However, such evidence has mainly been drawn from quantitative studies, and qualitative research investigating the link between PCOS, forms of psychopathology, and difficulties in weight loss is limited. Accordingly, further studies are needed, and the present report describes a qualitative study that seeks to help fill this gap.

Methods

The qualitative study from which the present paper is derived was cross-sectional in design and involved interviews with ten women, purposively selected,19 who suffered from PCOS and a comparative group of eight women without PCOS, all of whom made use of the VLCD-based weight loss program, ie, LLT. Focusing upon the “lived experience” of women with PCOS within an overall phenomenological approach,20–23 only results of the former are reported here.

The criteria used for the diagnosis of PCOS in the present study were as follows: a medical record of a diagnosis of PCOS (provided by a GP) or no medical record of PCOS. Furthermore, the study employed the following exclusion criteria: participants who had previously been assessed and excluded from taking part in the LLT program on account of their health and fitness linked to the following conditions: type 1 diabetes; porphyria; total lactose intolerance; major cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease; history of renal disorder or hepatic disease; active cancer; epilepsy; seizures; convulsions; major depressive disorder; psychotic episodes; schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, or delusional disorders; currently suffering from anorexia, bulimia, or undergoing treatment for any other eating disorder; pregnant or breastfeeding; given birth or had a miscarriage in the last 3 months, were excluded from the present study too. (Anthropometric, weight loss, and blood pressure data have been reported elsewhere).24

Interviews with both groups, based upon a semistructured interview schedule, were conducted between February and April 2013. The women were asked a series of questions grouped around four themes: experience of PCOS, interventions used to attain weight loss, experience of LLT, and outcomes and future models of intervention. The results were subject to thematic analysis,25,26 and a process of interrater reliability was used to establish themes. The latter were both inductively and deductively derived. Ethical approval for the study was obtained through the ethical and governance procedures of the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen and, in line with ethical practice, all participants have been anonymized. Written informed consent was also obtained.

Very low-calorie diet, LighterLife Total

The study sought to assess the usefulness, from a user perspective, of LLT, a VLCD based weight loss program offered by LighterLife. LighterLife is a commercial organization offering, among other things, a nutritionally balanced VLCD in conjunction with behavioral change therapy underpinned by group support. (LighterLife UK Limited, trading as LighterLife, is a company registered in England and Wales [company registration number 03164308], Harlow, Essex, UK).

In practice, LLT replaces conventional food with four food packs that provide a daily average of 600 kcal, 50 g protein, 50 g carbohydrate, approximately 17 g fat, and at least 100% of references intakes for vitamins and minerals. Participants are advised to stay adequately hydrated while on the program. LLT has two distinctive stages: weight loss and weight management. During each of these stages, clients attend weekly group meetings of four to twelve people that offer group support and counseling to encourage long-term behavioral modification and weight management, which are delivered by a trained LLT counselor. Following the weight loss period, participants are gradually reintroduced to conventional food, following a standardized protocol, where food packs are gradually decreased while the consumption of the conventional food is increased.

Findings

The findings are presented below in four sections: experience of PCOS, other weight loss interventions, experience of LLT, and model intervention.

Experience of PCOS

The women were first asked about three aspects of their experience of living with PCOS: length of time since PCOS diagnosis, symptoms, and impact of PCOS on day-to-day life. The following was found.

Time and diagnoses

There was some difficulty in establishing how long the women had suffered from PCOS as not all the participants (n=2) were sure when the actual diagnosis had taken place. The suggestion was that symptoms were experienced for some time in advance of diagnosis and that diagnosis itself was a process of recognition rather than an event. One participant explained:

I can’t really remember. I think it was probably in my late twenties but it was sort of over a long period having the various tests and you know when I originally went to the doctors it was for other symptoms. [PCOS8]

For the eight others, diagnoses took place between 2 and 21 years ago (at the time of the study), with an average of 10 years. As such, the women generally had lived with the condition for considerable lengths of time.

Symptoms

Participants were next asked about the symptoms that prompted them to seek medical advice. The women experienced a range of symptoms that caused them to act and highlighted a mix of reproductive problems (n=6), hirsutism (n=4), problems with weight (n=4), and skin disorders (n=3). Six women reported multiple symptoms.

Individual accounts illustrate the difficulties experienced and the ways in which the women, sometimes in negotiation with health professionals, prioritized their symptoms and acted upon them. Thus, two of the women highlighted a combination of weight problems and unwanted facial hair (combined with irregular periods in one case) as the determining factors in seeking help. One explained,

I used to have irregular periods and then they were heavy and lasted quite a long time when I had them and then also facial hair. And obviously I’ve always been overweight […] and it was mainly like the facial hair really, all on my neck and my chin and my face. [PCOS1]

Three other women received diagnoses following consultation with their doctors about fertility problems, whereas another woman received a diagnosis as a result of seeking help with delayed onset of her periods. She recalled,

I got diagnosed when I was seventeen […] I actually had an oscopy – when I was seventeen because, I never started my periods and they couldn’t understand why. [PCOS4]

Impact on life

The final aspect of the experience of PCOS examined was the impact of the condition on the day-to-day lives of the women involved. A range of issues were reported, with a combination of weight gain and social and psychological difficulties commonly cited.

Most respondents mentioned the impact of PCOS-associated weight gain on their physical and psychological well-being (n=7). Thus, putting on weight was associated with feelings of tiredness, guilt, and low self-esteem. One woman talked about her lack of energy and appetite, which nevertheless left her gaining weight:

Yeah, I mean obviously sometimes I can be really tired. Like, I can go days where I’m not hungry yet I’m still putting on weight. [PCOS3]

Elsewhere, another woman indicated that she felt constrained physically by PCOS and appeared also to harbor feelings of guilt about associated weight gain:

I’ve struggled with the weight gain issue and losing weight and controlling my weight. That’s had the most effect on me psychologically with the PCOS and, my everyday movement, because of excess weight or whether it’s been sweating or whether just feeling uncomfortable being overweight, whether it’s mentally right or wrong. [PCOS5]

Issues of self-worth, resulting in poor psychological health, were evident in the response of another woman. As such, a change in her physical appearance as a result of PCOS left her feeling bad about herself and vulnerable to depression. She explained,

Especially having been sort of a size eight to ten my self-esteem was really low, loss of libido, dry skin, increase in lethargy, mood swings […] very, very umm, low about myself. I wouldn’t say I was depressed but I didn’t feel good about myself. [PCOS8]

Two women also discussed the impact associated fertility problems had on their lives. For one woman, infertility attributed to PCOS had undermined a significant personal relationship,

It has ended quite a significant relationship because that it, well, contributed to that ending. It, yeah I mean it’s on my mind constantly because I don’t have children and I want to have children and it affects what I do. [PCOS6].

Other weight loss interventions

The second main topic explored with the women was the use of weight loss interventions prior to embarking on LLT. The women were asked about the types of weight loss interventions used, their motivation in using such interventions, the effectiveness of the interventions used, and any barriers experienced (with respect to achieving weight loss) when using such interventions.

Types of intervention

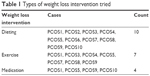

In trying to lose weight, all participants had tried various methods. Table 1 shows that the women had used three main types of intervention: dieting, exercise, and medication.

| Table 1 Types of weight loss intervention tried |

Dieting and exercise

The most reported method of seeking weight loss was dieting. All participants reported trying a variety of different diets prior to making use of LLT. On occasion, the women were directed to such diets by health professionals:

The doctor sent me to the dietitian. I’ve been on Cambridge diet, Slimmer’s World, Atkins, emm, yeah that’s about it really […] I regularly walk. I walk to work and home again so I’m walking about three miles a day, five times a week so that doesn’t help me lose weight but it helps me maintain my weight. [PCOS7]

Furthermore, the use and abandonment of multiple diets was a feature of the women’s experience. Dieting was often combined with exercise, in keeping with the regimens promoted by diet companies, and the women reported engagement in a number of fitness programs to complement a change in eating habits. One woman explained,

I don’t know where to start. Atkin’s, Rosemary Connelly several times, Weight Watchers, Slimming World […] And with the Rosemary Connelly, the exercising was a lot better. I joined a gym several times and then unjoined it several times. Umm, I’ve tried at home and we’ve had a personal gym instructor. But never really stuck at anything. [PCOS5]

Finally, another participant again indicated that dieting had been a long-term approach to her own weight loss, although in retrospect she felt that a lack of regular exercise over time might have been more significant. She explained,

I done some swimming but now I have two twins, they’re aged three. Twin boys, so that kind of gives me quite a lot of exercise but really I’ve never been a big exerciser, that’s been sort of one of my downfalls. [PCOS10]

Medication

The third main type of weight loss intervention tried was medication. Four women had tried a range of weight loss medications. One woman recalled her use of a prescription-based medication,

Emm, the only thing that I’ve tried, medication wise was, now what was it called, it was like emm, I got it through the doctor and it was, it’s when fat passes through your body […]. Xenical, that’s it. [PCOS10]

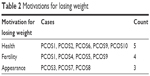

Motivations for losing weight

The study next explored the women’s motivation to lose weight. Three main reasons were advanced: health, fertility, and appearance (Table 2).

| Table 2 Motivations for losing weight |

Health

Five women mentioned that their motivation for wanting to lose weight was to improve their overall health. Responses indicate a complex understanding of the meaning of health, which was viewed as a mix of self-esteem, physical and psychological well-being, latent potential, and a moral obligation.27–31 Several women expressed a combination of these aspects of health. Thus, a mother with two young children explained her motivation to lose weight and become healthy as a combination of an attempt to improve feelings of self-worth, enhance her own physical and mental well-being, and as an obligation owed to her family. She reflected,

Well, the major incentive was my health, having, you know, the two little ones. I was struggling, emm, sort of to keep up with them, all very lethargic. I had an arthritis type condition which came with being overweight and, I felt very down in the dumps. So it was a bit of everything but initially it was health I thought, ‘I can’t have a stroke now with two young children so, umm, so that was my initial reason for losing it. [PCOS10]

Elsewhere another participant similarly sought treatments to enhance her own physical and mental well-being. However, for her, becoming healthy would also allow her to become a mother. She explained,

It’s because I am creeping towards middle age […] Emm, I want to be healthier. I don’t like feeling like this. I don’t, you know, I’m sore and I’m tired and I want to be healthy so that hopefully I can have children before I get too old because I know that if I want to have children and if I have problems with the polycystic ovaries that they’re not even going to look twice at me unless I’m a healthy weight. [PCOS6]

Fertility

The second factor motivating the women to lose weight was the perception that extra weight would compromise their fertility. As such, three women specifically wanted to lose weight to improve their chances of conception. Thus, a woman who had been trying to conceive for some time observed,

Obviously it increases your infertility as well. No matter what, I’ve never fallen pregnant. No matter if I’ve been fifteen stone, seventeen stone, eighteen. It’s never really, it’s never happened to me, no matter what. [PCOS1]

Appearance

Three of the women expressed concerns related to body image as a factor influencing their decision to seek to lose weight. Such a concern reflected issues in relation to body consciousness and self-objectification.32 With respect to the former, the women voiced concern about their physical appearance, expressed in terms of feeling dissatisfied with how they looked:

I think just to be happier within myself. I’ve never really liked myself, I’ve never really liked the way I looked although my partner is happy with the way I am. It’s not about anybody else, it’s about what I want. [PCOS3]

With respect to the latter, they acknowledged that their own sense of self-worth was heavily dependent upon how others judged their physical appearance. In short, although not inevitable, it mattered to them what others thought of their appearance, and they believed others judged them harshly. Thus, one woman explained her own struggle with body image and her perceived fear of being found wanting by members of her own family,

It was the birth of my nieces and nephews actually because I didn’t want them to have an Auntie that they were embarrassed to be seen with. [PCOS7]

Effectiveness and barriers

The interview then went on to explore how effective these weight loss interventions had been and the barriers to weight loss faced. The general picture that emerged was that such programs had been ineffective, especially in the longer term (Table 3). All participants reported a range of barriers to losing weight on using the various approaches tried.

| Table 3 Efficacy of other weight loss interventions |

Many of the women felt that the interventions used offered a very slow return on effort and as such caused them to become disheartened and to give up trying to lose weight. One participant explained,

Umm, not, not losing weight initially fast enough compared to how other people would and I suppose hardly losing any weight sort of knocked my motivation so it was a case of ‘Oh well, you know, I’m trying all the time to lose weight but I’m actually not so what’s the point?’. [PCOS8]

Another participant reported similar frustration with the speed of weight loss associated with the interventions used but alluded to a further confounding factor in the feeling of guilt that was associated with “managing” the slow weight loss by having the occasional “treat”. She explained,

I could lose probably up to half a stone and often, you’d have a better weight-loss in the first week, but then after that it becomes harder and harder to lose any weight […]. It can be really de-motivating because at the same time, you know, you’ve got to have a life and you feel guilty if you go out and have a really nice meal and have dessert and you end up, this complete guilt cycle of eating and feeling guilty. [PCOS4]

Another woman appeared to reach a plateau of weight loss beyond which she could not go and would then subsequently regain weight. She explained,

Every diet I manage to lose about two stone and I can’t lose any more. So I’ve never actually reached my goal, I’ve got very close to it but never reached it and then I just put it back on. [PCOS7]

Three women also reported that the speed with which they put weight back on following the abandoning of a diet was a barrier to successful dieting. One woman commented,

I felt poorly motivated and the weight that I lost, I did put back on again […]. To be truthful, I didn’t really lose a great deal. My weight sort of gradually, it crept up, umm so it’s maybe about half a stone a pop and with the appetite suppressants which I maybe lost about two stone but I did put that back on. [PCOS8]

Another woman found that the quantity and type of food she had to eat while dieting proved difficult to manage and a barrier to successful dieting, explaining,

Emm, just the sheer volume of food you were being asked to eat and the type of food as well. Emm, it was a lot of pasta and rice and, you know, a lot of the diet foods, things that are labelled as low fat, or diet this or diet that but whatever. I think there was a lot of reliance on them rather than actually proper, you know, portion control and things. [PCOS6]

Finally, one woman felt that her motivation to diet was linked to her own moods, and as such moods varied, then “she” was in fact the barrier to losing weight. She argued,

Myself, definitely. Emm, I’m very much, very much an emotional eater so if I was feeling a little bit low and also the fact that it’s so hard to lose weight and continue to lose weight and to stick at it so if anything was the barrier it was myself. It wasn’t other people, it was definitely kind of my own doing […] almost like self-sabotage. [PCOS10]

Experience of VLCD-based weight loss program – LLT

The interview went on to explore the women’s experience of LLT. In particular, the women were asked how effective the diet was in comparison with the other weight loss interventions tried; how useful the counseling sessions were; the problems encountered with LLT and the outcome of being on LLT. The following was found.

Effectiveness of LLT

All the women reported positively on LLT and highlighted a number of welcome features of the program including weight loss, adopting healthier lifestyles, and practicality (Table 4). All the women interviewed reported significant amounts of weight loss while on the program. However, they qualified this assessment with the observation that regaining some weight upon cessation of the diet was an expected feature of their experience too. Thus, one woman praised LLT while acknowledging her own supplementary weight gain upon coming off the diet.

| Table 4 Effectiveness of VLCD-based LighterLife Total |

That’s the best thing I did. It was the most weight I lost when I was on LighterLife. I lost five and a half stone but obviously as soon as you come off it you put about nearly two stone back on within a few months because you’re going back to normal food again and they told me that you would put on at least a stone, stone and a half when you come off LighterLife. [PCOS1]

Eight participants claimed that they have adopted a healthier and happier lifestyle after coming off LLT in an on-going pursuit to maintain a healthier weight. One woman explained:

I’ve actually, I just changed my lifestyle, I do exercise everyday which I never used to do so I do aerobics or Zumba or whatever but I do an hour at the gym every day. I just check my weight all the time to make sure that if I go over, if I gain a couple of pounds, I’ll never go over that. Then I go back to dieting, yeah, you usually put on I think when you have this condition […] I eat quite normally but I don’t eat potatoes, bread, pasta, anything like that. That’d just put the weight back on. [PCOS4]

Four of the women reported positively on how easy the diet was to manage, suggesting that it compared favorably with other diets in this respect. Thus, one participant was particularly appreciative of the food packs provided which ensured that she enjoyed a healthy diet, remarking,

It’s good I think because it sort of totally removes you from food so you can lose the weight quickly, and you don’t have to think about what you’re eating, calorie counting or making up meals because I’m not very good at cooking so I can’t be bothered to cook omelettes and things like that. [PCOS2]

Elsewhere, three women reported improvements in their ovarian health and menstrual cycles. Thus, one woman explained a positive assessment from her gynecologist following LLT, recalling,

I went to see my gynaecologist after I’d lost all the weight and I actually had healthy follicles on both ovaries. [PCOS6]

Finally, one woman highlighted an improvement in self-confidence, observing,

My confidence was boosted. I got promoted at work and I felt confident enough to travel. I did a lot of the things that I didn’t do before. [PCOS7]

However, two women felt resigned to always being overweight, despite experiencing LLT. For one, a failure on her part to engage with a related maintenance program after coming off the diet was at least partially to blame. She argued,

What I didn’t do, the biggest mistake is that I didn’t go and do the maintenance program and learn how to eat again but now, I’m not even convinced whether that would work because I’m not, you get yourself in to a mind-set where you think ‘I’m always going to be this weight because I’ve got polycystic ovaries so it doesn’t matter what I do.’ [PCOS4]

For another woman, a lack of motivation and willpower was her own assessment of a less than positive outcome from following LLT. She confessed,

I’m finding it hard to find the motivation because something comes up like a party and I just keep putting it off. Things just happen which is, I think, the hardest bit because when you start I think its fine but I do struggle in the end […]. LighterLife taught me a lot but I just can’t be bothered. I’m really lazy. [PCOS9]

Counseling

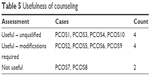

The interview next explored the women’s experience of the counseling sessions provided on LLT.

As Table 5 shows, eight women found the counseling sessions useful, half of whom offered a qualified endorsement of this part of LLT. Two women reported that they found the counseling sessions not useful.

| Table 5 Usefulness of counseling |

For those offering an unequivocal and positive assessment of the counseling sessions, the combination of counselor-led personalized support and peer support was highlighted as a crucial factor. The significance of such supports was in the information and understanding provided and in the motivation given to the women to continue dieting. Thus, one woman explained,

When I did LighterLife, we had a closed group and that worked really well because there was probably twelve or thirteen of us and we all got to know each other very well over three months and we all saw each other lose weight, we built up quite a bond while we were in it which kept the motivation going. [PCOS4]

For those offering a qualified endorsement of the counseling, satisfaction with the sessions, especially in relation to motivation to continue dieting, was tempered by a perception that beyond group counseling, postdiet interventions needed to include one-to-one support. In addition, the management of the group sessions was an issue for some. With respect to the former, one woman argued,

[…] I really looked forward to the counseling sessions and I needed them to keep motivating me, […] but I would like more, because […] before I used to get one-to-one help and now I don’t so before it used to be tailored and this time when I came off my diet they didn’t really help me in how I should come off my diet. [PCOS9]

With respect to the latter, enjoyment of the counseling sessions could be undermined by a failure of the counselor to manage strong characters who could dominate a group session. Thus, one woman recalled,

I did like the counselling sessions but there could be problems with the group. The participants not the poor counsellor. If there’s a very strong character in the group, the poor counsellor, they’re not as strong to be able to manage them. This person used to take over and you wouldn’t then get the full benefit because they’ll take too long dealing with them and next thing you know they haven’t got any more time. [PCOS5]

Two participants did not regard their counseling sessions as particularly useful. Such dissatisfaction arose out of perceived lack of empathy from the counselors involved:

Not really. Emm, the first, because I’ve been twice now, the first person was the one that accused me of eating […] And she hadn’t ever had a weight problem herself so she didn’t really understand, you know, the problems and the other lady that I went to […] she had followed the program but she wasn’t someone I would naturally warm to. [PCOS7]

Also, one woman complained about the failure of a counselor to properly manage all members of the group, which led to individual group members dominating sessions and undermined their value:

I mean in terms of the counselling sessions, which it, it sort of gave, it did give me some slightly more insight in to my attitude towards food but I think it was rather brief and rather superficial and as always when you get in group therapy, certain more vulnerable members would monopolise it. [PCOS8]

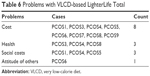

Problems with LLT

Although all participants enjoyed some success regarding weight loss on LLT, most participants also experienced difficulties with the program. In particular, four main problems were identified: cost, health, social costs, and the attitudes of others (see Table 6).

| Table 6 Problems with VLCD-based LighterLife Total |

Cost

Eight participants reported that the cost of the VLCD posed a problem. In January 2014, the cost of LLT food parcels was around £65 per week and counseling cost £15 per session. As such, adopting LLT made significant demands upon individuals’ budgets, as one woman explained,

LighterLife is good in one way but it’s not so good in the other, you know. It is a costly thing to do with money, especially with the new price changes that I can’t afford to do. [PCOS3]

Costly in absolute terms, the value of LLT was weighed against other commitments and outlays, and on occasion was not given priority, as another woman explained,

LighterLife was brilliant, absolutely brilliant but then our circumstances changed and we’ve now gone in to business and, we’ve been going through a prolonged recession time […] So I’ve had to cut costs, not just for my business but also my outgoings because that’s how life is at the moment. So, I would love to go back to LighterLife but I don’t think I’d be able. [PCOS5]

Finally, the cost of LLT was assessed in terms of its effectiveness and for some it did not appear to offer value for money. Thus, another woman argued,

Emm, no. I’ve stopped doing LighterLife. I started LighterLife again in January and I came off it again in February because I went away on holiday. I did then want to come back to LighterLife but I didn’t because obviously it’s very expensive, and I didn’t find I was getting enough help from them so I didn’t see the point. [PCOS9]

Health problems

A second problem reported was the subjective view that ill-health resulted from following the diet. Three women felt that they had encountered health problems in this way. Thus, one woman explained how the initial effectiveness of the diet, in terms of significant weight loss, was tempered in time by increasing ill-health. She recalled,

When I did the LighterLife I thought I saw results instantly and that was amazing but then I went from one extreme to another, I went to an extreme where I’d lost loads of weight and I didn’t look good for it, I looked ill, and then I actually became very ill. [PCOS3]

Social costs

Three of the women highlighted the social dimension of food and how adopting LLT restricted their opportunity to engage with others in terms of sharing meals. Thus, although assured that LLT would not be an obstacle to eating and mixing with others, the reality was that following the diet did limit social contact in some way. One woman explained,

LighterLife was the one that was the most successful for me and I lost three stone and obviously the barriers to that was going into ketosis for long periods of time and the social issue it causes because you literally, I know they say you can go out and do what you like but it’s very hard when you want to go out and socialise. So for three months it does restrict your life a bit. [PCOS4]

Other people’s attitude

Finally, one woman reported problems caused by the attitudes of others toward the diet and her associated weight loss:

I found the, the support from outwith my group varied immensely. I had some friends who actually told me that they hated it and I remember one incident at a wedding where it was with some people from University and they knew I was doing the plan. Initially they’d been quite supportive but when I got to a point where they thought I had lost enough weight they become quite hostile and I did actually have a friend complain said, ‘But I’m the only fat one left now’. [PCOS6]

Model intervention

By way of concluding the interview, the women were asked what they would consider to be a model weight loss intervention for women with PCOS. Four dimensions were highlighted as being crucial to any such program: food, meetings, exercise, and speed of (weight) change (Table 7).

| Table 7 Model intervention |

Identifying the “correct” types of food was the most reported element of any new approach to devising a weight loss intervention. Doing so was a combination of promoting the use of a diet lower in starch, prescribing foods that could be more readily sourced, and offering menus that were less restrictive and allowed for high-protein meals that were more compatible with “eating out”. Thus, one woman called for a diet with fewer carbohydrates, arguing,

[…] maybe they could do a specific diet for people with polycystic ovaries because I think the starchy stuff, you know, the carbs like bread and crisps and things like that I just don’t think that we can eat that because I think it makes my stomach very bloated. [PCOS2]

Another called for a diet built around foods more easily found in the supermarket. Thus, although LLT offers a total dietary replacement approach obviating the need to source additional foods, she argued,

It [LLT] was very good but it’s just so restrictive on what you can [eat], the things that you use in it, they’re not everyday items. You need to hunt them down. There’s actually lists of foods. It looks like a lot but it’s not lots of everyday food that you can get every day in a supermarket sort of thing. [PCOS5]

Another woman sought a (new) intervention that allowed the user to continue to enjoy the social aspect of food and partake of a diet that others, not dieting, enjoyed. She explained,

You’ve to have options as well because LighterLife is very restrictive but to have, you know, kind of like a list of things like of high protein foods or vegetables, you could have if you were going out for a night out or if you were invited somewhere. It could be awkward because sometimes it is really awkward to have a shake or whatever because people, you know, it’s, because it is such a private thing. [PCOS6]

The women’s ideas around developing a new weight loss program imply that the frequency and types of meetings offered to participants need some attention. Thus, more frequent meetings and one-to-one meetings were variously called for. One woman explained,

LighterLife is great but if you had the perfect system for women with PCOS, it would be to have maybe more regular meetings. To have maybe two or three meetings a week to start with because, you know, you can do a couple of days and you’re okay but then you think actually I need, that little boost, need that check-in. [PCOS6]

While another argued,

I would do something with LighterLife. I would do something with more one-to-one so it’s based on the individual. [PCOS9]

With respect to exercise, it was suggested that an increased, set amount of exercise would be necessary in a new model of weight loss. One woman explained the need for such exercise and argued,

Yeah, it probably would be like the LighterLife, but obviously I’d say increase exercise as well would help […] half an hour of exercise or walking a day or something like that. [PCOS2]

Finally, any new program would need to revisit the speed at which women with PCOS were expected to lose weight. In particular, it was felt that an extended time period that allowed the women a higher calorie intake would enable them to better adjust to changes in body weight. Thus, one woman satisfied with LLT, explained,

I don’t think you should do it as quickly for women with polycystic ovaries, I think the weight-loss should be slower. So actually, whereas on the very low calorie diets you were on kind of five-six hundred calories a day, I think it should be higher than that but still in ketosis but over a longer period of time because to try and get your body to adjust to the changes. Not being ketosis for too long because, I don’t know about other PCOS women but my, I had a lot of hair loss which is why I would be scared to do it again. [PCOS4]

Discussion

Like other studies of women with PCOS,4–7 this study found that the participants experienced a number of distressing symptoms, such as weight gain, facial hair, acne, and fertility problems, which, over time, led to their diagnosis with the condition. Again in line with other studies,9–15 the research participants reported feelings of low self-esteem and depression alongside a poor QOL, all of which they linked to their medical condition and obesity. Such experiences would form part of the motivation to seek remedy for their situation. Lifestyle changes are most commonly promoted in such circumstances, although research indicates that for certain obese women with PCOS, bariatric surgery can be effective.33

In the present study, the participants’ experience of weight loss interventions indicated that a range of (nonsurgical) approaches were used, involving exercise, medication, and dieting. The latter was the most reported and resulted in the women’s use of popular diets, such as Weight Watchers and Atkins, where weight loss was minimal and regained quickly, a finding consistent with earlier reports that women with PCOS face additional barriers when trying to use weight loss strategies.16 Attempting to understand such repeated attempts and failures to attain acceptable weight loss, the study found that the women were motivated to try through a combination of concerns about health, appearance, and fertility. Thus, some recognized the value of physical and mental well-being (including the importance of self-esteem) and sought to attain both. They recognized latent potential (eg, to be mothers) and sought to realize it, and they were driven by a moral imperative to be fit enough to care for family members. Others were driven by the pressures of the wider culture (often internalized) to attain an acceptable physical appearance, raising issues of body consciousness, and self-objectification.

Regarding LLT, the present study found that women experienced more significant and rapid weight loss compared with other weight loss interventions.18 This resulted in improvements in self-esteem,34 which may partly account for the women adopting a healthier lifestyle and, in turn, maintaining a significant amount of the weight loss on this VLCD. Indeed, all the women recommended LLT as the model weight loss intervention with some slight modifications to accommodate the particular needs of women with PCOS. As such, any future weight loss programs should combine four key elements: the “correct” food (ie, low in starch, easily obtained and flexible enough to allow, occasionally, for higher levels of protein), more frequent meetings that combined group support and one-to-one sessions, more frequent exercise, and a more relaxed timetable for expected weight loss that allowed for bodies to adjust to any change. Although no explicit examination of the women’s economic circumstances was carried out, the perceived high costs associated with adopting LLT, was reported as a barrier for some of the women, alongside concerns about health.

Conclusion

This study explored the experience of ten women with PCOS, who had tried to lose weight on the VLCD, LLT. Drawing upon the accounts of the women themselves, the study pointed to the chronic and distressing symptoms that the women experienced as a result of the condition and how a mix of psychological, physical, and social factors, linked to health, appearance, and fertility caused them to seek remedy for excessive weight gain through a variety of interventions. The latter included a mix of dieting, exercise, and medication, none of which were effective in the long term. Similarly motivated to try LLT, the women reported greater and more sustained weight loss (alongside improvements in reproductive, physical, and psychological well-being), suggesting that an effective solution to their difficulties might be found. Indeed, when invited, the women endorsed LLT and went on to call for a nuanced dietary program that included a VLCD of “balanced” foods (based upon produce that could be sourced locally through supermarkets and therefore affordable and socially acceptable), frequent meetings (including one-to-one sessions), exercise, and an acceptance that weight loss would be slower, thus enabling women with PCOS to adjust to changes in body weight.

These qualitative data taken in conjunction with those quantitative data already published from this retrospective study (and cited earlier) outline the need for a more appropriate prospective clinical trial of VLCD in the management of obese PCOS patients, where metabolic, hormonal, and fertility issues can be addressed in the trial design. Unusually, VLCD management of obese PCOS patients demonstrates similar weight loss to obese patients without PCOS, a similar situation to the management of obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients.35

Disclosure

The research was funded by an educational grant from LighterLife. Broom was the Medical Director for LighterLife at the time of the research. Johnson is the Head of Nutrition and Research at LighterLife. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Asuncion M, Calvo RM, San Millan JL, Sancho J, Avila S, Escobar-Morreale HF. A prospective study of the prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected Caucasian women from Spain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2434–2438. | ||

Hopkinson ZE, Sattar N, Fleming R, Greer IA. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: the metabolic syndrome comes to gynaecology. BMJ. 1998;317(7154):329–332. | ||

Michelmore KF, Balen AH, Dunger DB, Vessey MP. Polycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;51(6):779–786. | ||

DeUgarte CM, Woods KS, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Degree of facial and body terminal hair growth in unselected black and white women: toward a populational definition of hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(4):1345–1350. | ||

Escobar-Morreale HF, Luque-Ramírez M, González F. Circulating inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(3):1048–1058.e2. | ||

Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1523–1529. | ||

Boeka AG, Lokken KL. Neuropsychological performance of a clinical sample of extremely obese individuals. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(4):467–474. | ||

Hoeger KM, Oberfield SE. Do women with PCOS have a unique predisposition to obesity? Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):13–17. | ||

Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Slade T, Brownhill S, Andrews G. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV major depression in an Australian national survey. J Affect Disord. 2003;75(2):155–162. | ||

Elsenbruch S, Hahn S, Kowalsky D, et al. Quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5801–5807. | ||

Grogan S. Body image and health. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):523–530. | ||

McCook J, Reame N, Thatcher S. Health-related quality of life issues in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(1):12–20. | ||

Hahn S, Janssen OE, Tan S, et al. Clinical and psychological correlates of quality-of-life in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153(6):853–860. | ||

Trent ME, Rich M, Austin SB, Gordon CM. Quality of life in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Paediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):556–560. | ||

Weiner CL, Primeau M, Ehrmann DA. Androgens and mood dysfunction in women: comparison of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome to healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):356–362. | ||

Moran L, Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Deeks A. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a biopsychosocial understanding in young women to improve knowledge and treatment options. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31(1):24–31. | ||

Herriot AM, Thomas DE, Hart KH, Warren J, Truby H. A qualitative investigation of individuals? Experiences and expectations before and after completing a trial of commercial weight-loss programmes. J Hum Nutr Dietet. 2008;21(1):72–80. | ||

Rolland C, Johnson KL, Lula S, MacDonald I, Broom I. Long-term weight-loss maintenance and management following a VLCD: a 3-year outcome. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(3):379–387. | ||

Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. | ||

Schutz A. The Problem of Social Reality. The Hague: Nijhoff; 1962. | ||

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Enquiry. Newbury Park: Sage; 1985. | ||

Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Ontario, Canada: The Althouse Press; 1990/1994. | ||

Smith AS, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London, UK: Sage; 2009. | ||

Nikokavoura EA, Johnston KL, Broom J, Wrieden WL, Rolland C. Weight loss for women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome following a very low-calorie diet in a community-based setting with trained facilitators for 12 weeks. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:495–503. | ||

Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. | ||

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. | ||

Cronin de Chavez A, Backett-Milburn K, Parry O, et al. Understanding and researching wellbeing: its usage in different disciplines and potential for health research and health promotion. Health Educ J. 2005;64:70–87. | ||

Downie RS, Macnaughton J. Clinical Judgement: Evidence in Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. | ||

Blaxter M. Health and Lifestyles. London, UK: Routledge; 1990. | ||

Blaxter M. Health. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2004. | ||

Seedhouse D. Health: The Foundations for Achievement. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2001. | ||

Tiggerman M, Lynch JE. Body image across the lifespan in adult women: the role of self-objectification. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(2):243–253. | ||

Kyriacou A, Hunter AL, Tolofari S. Gastric bypass surgery on women with or without polycystic ovary syndrome – a comparative observational cohort analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(2):e23–e24. | ||

Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Sardinha LB, Lohman TG. A review of psychosocial pre-treatment predictors of weight control. Obes Rev. 2005;6(1):43–65. | ||

Rolland C, Lula S, Jenner C, et al. Weight loss for individuals with type 2 diabetes following a very-low-calorie diet in a community-based setting with trained facilitators for 12 weeks. Clin Obes. 2013;3(5):150–157. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.