Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

The Effects of Leaders’ Prosocial Orientation on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior – The Roles of Affective Commitment and Workplace Ostracism

Received 15 June 2021

Accepted for publication 22 July 2021

Published 6 August 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1171—1185

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S324081

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Dan Wang,1 Yunyun Qin,1 Wenjie Zhou2

1School of Business Administration, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, 125105, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yunyun Qin; Dan Wang Tel +86-18342942214

; +86-13591991056

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: According to leadership trait theory, leaders’ personality traits are stable factors in organizational situations and exert significant effects on employees’ organizational behaviors. However, studies related to this topic are very limited. In this study, from the leadership trait perspective and based on social identity theory and social exchange theory, the influencing mechanisms of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors are investigated. Specifically, leadership prosocial tendency, affective commitment and workplace ostracism are selected as the independent variable, mediating variable and moderating variable, respectively.

Methods: The data collection is conducted in two stages in which the leader–employee pairing method is adopted. Ultimately, 347 valid questionnaires are collected from 73 teams. Later, the hierarchical regression analysis and bootstrap methods are used to test the study’s hypotheses.

Results: Leadership prosocial tendencies have significant positive effects on affective commitment (β = 0.282, p < 0.001), affiliation-oriented (β = 0.648, p < 0.001) and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors (β = 0.521, p < 0.001). There is a significant positive effect of affective commitment on affiliation-oriented (β = 0.103, p < 0.05) and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors (β = 0.122, p < 0.05). At the same time, the influence of leadership prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented (β = 0.619, p < 0.001) and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors (β = 0.487, p < 0.001) remains significant. In other words, affective commitment partially mediates the relationships between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affiliation-oriented, challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Workplace ostracism plays a negative moderating role between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affective commitment (β = − 0.098, p < 0.05). Furthermore, workplace ostracism can also mediate the mediating role of affective commitment with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals [− 0.146, − 0.017] and [− 0.114, − 0.003].

Conclusion: The results show that leaders’ prosocial tendencies have significant positive effects on both affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Affective commitment partially mediates the relationships between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Workplace ostracism significantly negatively moderates the relationship between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affective commitment. Moreover, the study verifies that the mediating effect of workplace ostracism on affective commitment has a significant moderating effect.

Keywords: leader’s prosocial orientation, affiliation-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, affective commitment, workplace ostracism

Introduction

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), as an extrarole behavior that has a positive effect on organizational performance (OP) and growth, has always been the focus in the field of organizational behavior. Today, organizational operating environments are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambivalent, especially those against the background of rapidly growing economies.1 With the aim of adapting to the dynamic business environment and gain competitive advantages, organizations should pay attention to the soft power created by “good employees” in addition to hard power, eg, effective management systems, efficient operational processes, and advanced technology.2 Specifically, soft power refers not only to the human resource benefits demonstrated in employees’ work but also to the innovative and challenging behaviors that employees demonstrate outside of work. Therefore, OCB has become an important source of power for organizations to achieve competitive advantages in complex and uncertain environments.3 Many studies focus on OCB to help organizations become more adaptive and competitive.

Previous studies have mainly investigated employees’ OCB in terms of influencing factors and outcome variables. A review of the literature4–10 shows in the OCB research, limited attention has been given to the following two aspects. On the one hand, many studies focus only on the general forms of OCBs with a concentration on self-voluntary and prosocial behaviors. More recent studies suggest that there are two complementary types of citizenship, namely, affiliation-oriented OCB and challenge-oriented OCB.11 The former behavior is a type of organizational citizenship behavior that centers on consolidating interpersonal relationships and maintains the organization’s current status and social relationships. The development of existing organizational tasks can be prompted by this behavior.12 The latter behavior refers to the transformational efforts related to work styles, policies, and procedures proposed or implemented by individuals. Such behavior challenges the current status of an organization and aims to improve organizational performance.13 From a contingency perspective, Li et al14 noted that affiliative behaviors exert a positive influence in relatively stable organizational situations, whereas challenging behaviors are more helpful for organizations in complex and unpredictable environments. As organizations’ business environments can shift over time between stable and unstable states, the affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs are helpful to organizations’ survival and success. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the above two OCBs. On the other hand, previous studies have focused on investigating the influencing factors of OCBs from the perspective of individual employees and the external environments. For example, individual employee psychological factors include job satisfaction,5,15 organizational commitment,8,16 self-efficacy9,17 and insider identity perceptions,18,19 and external environmental factors include transformational leadership,2 servant leadership behaviors20 and authoritative leadership.21 Currently, the exploration of external environmental influences focuses on the “leader”. As a key situational driver, leadership’s impact on employees’ OCB has received much attention in recent years. However, most studies have explored the influence of leadership on OCB from a behavioral perspective, and few studies have explored it from a trait perspective. As stated by Derue et al,22 in addition to the behavior perspective, the trait perspective is another important perspective to study the mechanisms of how leaders affect employees’ behavior. A leader’s personality traits are a more stable predictor of organizational behavior in organizational situations. This deep-seated factor is an important perspective for predicting employee behavior because it does not easily change with the influence of other organizational situational factors. At present, few studies have explored organizational behavior from the perspective of leader traits, which needs to be further studied.

With the aim of exploring the influencing mechanisms of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on OCBs, the personality trait of prosocial tendencies is selected as the antecedent variable in this study from the leadership trait perspective. In the situation of Chinese organizational management, leaders are affected by traditional Chinese culture and tend to pay attention to aspects of Confucianism such as “benevolence”, “people-oriented”, and the ethos of “cultivating oneself and others”. Leaders with a “people-oriented” philosophy understand that employees are an organization’s greatest source of capital and power. Therefore, such leaders engage with employees as the organization’s core and pay attention to employees’ interests. Moreover, the philosophy of “cultivating oneself and others” emphasizes that leaders should set good examples and pay attention to the cultivation of morality. Based on the “benevolence” philosophy, leaders realize that they should care for, look after and treat employees like family at work to build a harmonious working environment. Therefore, the leadership personality trait of “prosocial tendencies” is widespread in Chinese organizations. In this study, enterprises located in Shandong, Liaoning and Hebei provinces of China are selected to investigate the relationship between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and OCBs. These locations were selected as they are situated near the birthplace of Confucius (the founder of the Confucian school). Due to the geographical advantage, the selected three provinces are deeply influenced by Confucianism. In organizations, leaders with a high level of prosocial orientation are willing to provide humanitarian help and pay attention to employees’ interests.18 Therefore, based on the reciprocity principle, employees under such leadership may have a strong sense of giving back to the organization.15 Such employees might be motivated to implement OCBs that are beneficial to the organization. It is necessary to study the relationship between the leader’s prosocial orientation and employees’ OCBs and reveal the underlying mechanisms.

In this study, affective commitment is selected as the mediating variable to study the influencing mechanisms of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. According to social identity theory, the psychological factors of individual perception, such as employees’ affective commitment, can act as important mediating variables in the path of leadership influence on employees’ behaviors. Furthermore, many studies23,24 point out that affective commitment acts as a mediating variable between leadership and employee behavior. Zhou et al23 demonstrated that affective commitment mediates the relationship between humble leadership and employee constructive behavior. Phomane et al24 showed that affective commitment has a mediating effect between transformational leadership and employees’ innovation behavior. Thus, affective commitment is selected as the mediating variable in this study. As a key situational factor in organizations, leadership style significantly affects employees’ cognition and emotion, which ultimately has an impact on their behaviors. Specifically, leaders with a high level of prosocial orientation are more attentive to employees’ emotional changes and show more care, support and encouragement.5 As a result, employees will develop a high sense of belonging and identification with the organization, which will further increase the level of affective commitment. Moreover, Bizri et al25 showed that affective commitment has a direct impact on employees’ OCBs. Therefore, affective commitment can be treated as a key psychological path through which the leader’s prosocial orientation affects the implementation of employees’ OCBs. In addition, the boundary conditions between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and employees’ OCBs are explored in this study. Based on social cognitive theory, as an external environmental factor, workplace ostracism can affect employees’ psychological states.26 In summary, we posit that workplace ostracism plays an important moderating role between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affective commitment. Specifically, workplace ostracism, as an important organizational situational factor, can threaten the individual’s psychological state in terms of aspects such as self-esteem, sense of belonging, control and self-existence value.2 Furthermore, employees with a high perception level of workplace ostracism are more likely to feel a discordant atmosphere in the organization and experience exclusion from colleagues and leaders. As a consequence, such employees’ sense of belonging and emotional dependence on the organization may be reduced. In this condition, employees’ emotional commitment to the organization can be significantly affected. Therefore, workplace ostracism can be treated as an important situational factor that can influence the effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ affective commitment. Moreover, the indirect effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ OCBs through affective commitment may also be affected.

The main contributions of this study are as follows. (1) From the perspective of leadership traits, the psychological paths and boundary conditions of leaders’ prosocial tendencies to influence OCB are explored, which provides a new perspective for studying the influencing factors of OCB. (2) From the perspective of psychology, the mechanisms of the mediating role of leader personality traits on OCB are revealed. Specifically, affective commitment is selected as the mediating variable. This proves that affective commitment mediates the influence of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. This has theoretical implications for opening the “black box” of the influencing process of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on OCB. (3) A moderated mediating model is established by introducing the important organizational situation of workplace ostracism as the boundary condition. Under the proposed model, the differences in leadership effectiveness under different workplace cold violence situations can be considered. The study also has significant implications the knowledge improvement with regard to the influencing mechanism of leadership traits on employees’ OCBs.

Theoretical Basis and Hypotheses

Leader’s Prosocial Orientation and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

As a hot research topic in the psychology field, a prosocial orientation is an altruistic value tendency that focuses on the needs and welfare of other people.27 Generally, a prosocial orientation consists of mutual aid, humility, altruism, sharing, and cooperation.28 A leader’s prosocial orientation is manifested by caring for employees, valuing their interests, and providing them with emotional support, time, and material and other resources as needed. A leader’s prosocial orientation can not only lead to more harmonious interpersonal relationships but also affect the survival and development of the organization.29 OCB is a type of extrarole behavior that is spontaneously developed by organization members. It is not included in the organization’s formal reward and punishment system but has positive effects on the performance and growth of the organization.30 Using Vandyne’s division method based on typological ideas,11 OCBs can be classified into two categories from different perspectives: affiliation-oriented OCB and challenge-oriented OCB. The former behavior is a type of organizational citizenship behavior that centers on consolidating interpersonal relationships and maintaining the organization’s current status and social relationships. The development of existing organizational tasks can be promoted by this behavior.12 The latter behavior refers to the transformational efforts proposed or implemented by individuals with regard to work styles, policies, and procedures. Such behavior challenges the current status of an organization and aims to improve organizational performance.13

A leader’s prosocial orientation is a relatively stable, deep-seated personality trait that is prevalent in management situations. It exerts significant effects on employees’ OCBs. On the one hand, leaders with a high level of prosocial orientation are more concerned about the well-being of employees. They always care and give timely help to employees,31 which may even extend beyond the scope of their job duties. More empathy, compassion, understanding and support are provided to employees by such leaders.32 When employees feel care and attention from leaders, they will have a strong sense of belonging and form cognitions as “inner employees” in the organization. Employees are encouraged by this perception to take initiative in their civic duties and proactively serve the organization.33 For example, under leaders with this trait, employees will actively participate in work, comply with rules and regulations, help colleagues build a harmonious atmosphere, protect the honor and interests of the organization. Furthermore, the generation of affiliation-oriented OCB among employees will be promoted. On the other hand, leaders with a high level of prosocial orientation focus more on cooperative and win-win relationships with employees. They tend to delegate more to employees and give timely support in terms of work resources.34 Based on the mechanism of reciprocity, when employees perceive support and trust from leaders, they will develop a sense of responsibility to help the organization achieve its goals.35 When employees feel responsible for the organization,36 they will be obligated to engage in behaviors that will benefit the organization. They will express concern about existing situations and take initiatives to give back to the organization through constructive effort.35 Thus, the generation of challenge-oriented OCB among employees will be promoted. Based on the above discussions, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): A leader’s prosocial orientation has positive effects on employees’ affiliation-oriented OCB.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): A leader’s prosocial orientation has positive effects on employees’ challenge-oriented OCB.

The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

Affective commitment refers to an individual’s identification with an organization’s goals and values, emotional attachment, and level of commitment to the organization.37 It represents the employee’s inner motivation to devote to the organization and influences the employee’s degree of work involvement. It is a high-level emotional factor for organizations and is also an internal motivation that drives employees to engage in positive behaviors for the organization’s benefit.38

According to social identity theory, employees’ behaviors can be affected by leaders by changing their cognitive, emotional and psychological states. Specifically, leaders with a high level of prosocial orientation tend to care and help their employees and give timely support to employees by providing various resources. They will actively convey the organization’s care, support and trust to employees. This positive exchange between leaders and employees can enhance employees’ senses of belonging and identification with the organization. Employees who feel valued by the organization will develop psychological perceptions of being very closely connected to the organization.30 This can result in the employees experiencing high emotional dependence on the organization. Thus, employees’ affective commitment to the organization will be reinforced, which will thereby strongly influence their work attitudes and behaviors.39 Many studies have shown that positive outcomes can often be obtained with the implementation of affective commitment. Moreover, affective commitment is an important antecedent for employees’ task performance, organizational citizenship behavior,3 creativity, and innovative behavior.40 Feldman et al41 pointed out that employees will actively implement extrarole behaviors when they develop emotional attachment to the organization. On the one hand, employees with a high level of affective commitment tend to identify highly with the organization, and their personal values will be highly compatible with the organization’s values.30 Such employees tend to be proactive in their work to help the organization achieve its goals. Under this situation, employees can develop great enthusiasm and dedication to their work and invest much time and effort to improve job performance.37 At the same time, such employees will be spontaneously concerned about the interests and development status of the organization. They will be more inclined to establish harmonious working relationships with colleagues and help each other at work.42 This will promote the implementation of affiliation-oriented OCBs among employees. On the other hand, a high level of affective commitment often implies a high-quality exchange relationship between leaders and employees.43 Under such organizational conditions, employees will receive a greater degree of empowerment and adequate resources, which can ensure job autonomy and effectively enhance psychological security and a sense of responsibility.35 Based on the principle of reciprocity, such employees will demonstrate willingness to give back to the organization and practice pro-organizational behaviors with the purpose of balancing the exchange relationship and improving their self-image.44 Such participation in organizational development is regarded as the responsibility and obligation of employees.37 Meanwhile, a high sense of psychological security causes employees to be unafraid when they face potential risks and failures in transformative behaviors.45 Employees will be more inclined to share tasks and demonstrate positive building behaviors to their leaders, which will promote the generation of challenge-oriented OCB. In contrast, employees with a low level of affective commitment lack a sense of mission and belonging to the organization, and they will be mostly unenthusiastic about work and less likely to take initiative to engage in extrarole behaviors. In summary, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Affective commitment has a mediating role between leaders’ prosocial orientation and affiliation-oriented OCBs.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Affective commitment has a mediating role between leaders’ prosocial orientation and challenge-oriented OCBs.

The Moderating Effect of Workplace Ostracism

Workplace ostracism refers to unfair treatment of employees such as through exclusion or neglect by others in the workplace.46 In Chinese organizational situations, the influences of traditional culture, such as “relationship-based” influences and the influence of “community thinking”, are obvious. Thus, workplace ostracism is a common phenomenon that has evolved into a common form of workplace “cold violence”. In general, employees who perceive high levels of workplace ostracism feel ignored or isolated by others. However, employees who perceive low levels of workplace ostracism believe that others treat them as insiders and care about their needs and feelings.47 It is evident that workplace ostracism is a very important factor that affects employees’ cognitions, emotions, and behaviors.

Employees with a high perception level of workplace ostracism are more sensitive to the information transmitted by colleagues and leaders, and they are more likely to develop negative emotions.48 Eventually, under such conditions, employees can form negative perceptions of the organization. They may overinterpret a thoughtless remark by a colleague as hostility and feel that the colleague is targeting them. When leaders care about or help other colleagues, such employees can feel left out and neglected.47 Resentment, anxiety and other negative emotions can fill their thoughts. In addition, such employees often feel that they are sidelined at work and tend to worry that they are not doing well in some areas, which causes others to dislike them.49 Over time, these behaviors will enhance these employees’ sense of alienation from the organization and greatly reduce their sense of belonging and emotional attachment to the organization.50 An employee’s affective commitment to an organization is influenced by a leader’s prosocial orientation simply as a result of the leader’s promoting the employee experience a sense of belonging and emotional attachment to organization. The positive effects of a leader’s prosocial orientation on employees’ affective commitment can be weakened by a high perception level of workplace ostracism. Employees with a low perception level of workplace ostracism believe that they are treated as insiders and that their needs and feelings are well cared for by others in the organization.51 Therefore, leaders with a prosocial orientation are more likely to be treated and appreciated by employees with a low perception level of workplace ostracism. Employees’ affective commitment to the organization is more likely to be shaped by a leader’s prosocial orientation. In summary, the following hypothesis can be obtained:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Workplace ostracism has negative effects on the relationship between a leader’s prosocial orientation and employees’ affective commitment.

Furthermore, the relationship between a leader’s prosocial orientation and employees’ OCBs is mediated by affective commitment. It may be that the mediating effect is also moderated by workplace ostracism, ie, there is a moderated mediating effect. Specifically, workplace ostracism refers to the employees being ostracized or neglected by others in the workplace, such as avoiding contact, suffering from cold feet or having their legitimate needs ignored. Workplace ostracism causes tremendous psychological damage to employees, resulting in a reduced sense of belonging and emotional attachment to the organization. Employees with high levels of perceived workplace ostracism have difficulty perceiving goodwill from the organization because they have a deep sense of distance from other members of the organization. In this condition, employees have a low sensitivity to the leader’s prosocial tendencies. In other words, it is difficult for leaders’ prosocial tendencies to positively influence the employees with higher levels of perceived workplace ostracism, thereby reducing employees’ emotional commitment to the organization and further inhibiting the generation of organizational citizenship behaviors. Conversely, for employees with low levels of perceived workplace ostracism, they believe that the organization will take care of their needs and treat them as “insider”. Therefore, for employees with low levels of perceived workplace ostracism, they will deepen their perception that the organization cares and values them, further increasing their emotional commitment to the organization and promoting organizational citizenship behavior. It can be illustrated that workplace ostracism can moderate the mediating effect of affective commitment. Furthermore, the following hypotheses are put forward:

Hypothesis 6 (H6): The mediating role of affective commitment on the relationship between a leader’s prosocial orientation and employees’ affiliation-oriented OCB is moderated by workplace ostracism. The stronger the workplace ostracism, the weaker the mediating effect will be. Conversely, the weaker the workplace ostracism, the stronger the mediating effect will be.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): The mediating role of affective commitment on the relationship between a leader’s prosocial orientation and employees’ challenge-oriented OCB is moderated by workplace ostracism. The stronger the workplace ostracism, the weaker the mediating effect will be. Conversely, the weaker the workplace ostracism, the stronger is the mediating effect will be.

From the above analysis, the theoretical model can be proposed as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Study Design

Participants and Procedures

The data in this study were collected from 14 enterprises in the Shandong, Liaoning and Hebei provinces of China including state-owned enterprises and private enterprises.The sample includes 80 teams and covers 6 different industries including construction, manufacturing, real estate, and finance. The member number of a participating team was guaranteed to be at least 3. Meanwhile, employees and leaders must have worked together for more than 6 months.Before the formal survey was conducted, a presurvey was performed to improve the participants’ understanding of the questionnaire. After the presurvey, the questionnaire was revised and improved based on feedback. When distributing questionnaires, all participants were informed that the questionnaires would be used for scientific research purposes only and that all information would be kept strictly confidential. We also guaranteed that the information filled in by participants would not have any influence on the individuals and the company they work for. A leader–employee pairing approach was used in the questionnaire collection to reduce the effects of common method bias on the data quality and study results. To analyze the data conveniently, the questionnaire numbers were the same for all employees on the same team, and the number varied from 1 to 80, corresponding to the 80 teams. The questionnaire survey was carried out twice with an interval of one month. For the first stage, the questionnaires were completed by the employees, and demographic data were collected including gender, age, working years and educational background. The questionnaires regarding prosocial orientation were completed by the leaders of each team, and the questionnaires about affective commitment and workplace ostracism were completed by the employees. For the second stage, the employees evaluated their own OCBs one month later.

A total of 430 questionnaires were distributed, and 372 were successfully returned. Invalid questionnaires were removed including incomplete questionnaires, questionnaires with obvious regularity and questionnaires that did not match the leader–employee pairs. Eventually, there were 347 valid questionnaires from 73 teams, and the valid feedback rate was 80.7%. Among the valid questionnaires, 59.9% were male and 40.1% were female. In terms of age, 11. 4% were under 25 years old, 33. 7% were 25 to 35 years old, 34. 5% were 35 to 45 years old, and 20. 4% were over 45 years old. For education background, below high school accounted for 6.9%, high school accounted for 11.7%, junior college accounted for 19.6%, bachelor’s degree accounted for 39.7%, and master’s degree and above accounted for 22.1%. For the working years, 1 year or less accounted for 9.7%, 1 to 3 years accounted for 34.7%, 3 to 5 years accounted for 35.2%, and more than 5 years accounted for 20.4%.

Measures

The data were collected by questionnaires. For the scales used in this study, some revisions were made regarding the specific issues based on the mature scales widely used by many researchers. All the questionnaire data were measured using a five-point Likert scale except for the statistical variables, and the values ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

For the leaders’ prosocial orientation, the scale from Feldman et al52 was used and included 8 question items. A sample item was “In any group, I believe the dignity and welfare of employees is the most important”. The value of the internal consistency coefficient α was 0.852.

For affective commitment, the scale from Allen et al53 was adopted and included 6 question items. An example was “I would like to spend the rest of my career in the current company”. The value of the internal consistency coefficient α was 0.845.

For workplace ostracism, the scale from Ferris et al46 was used and included 10 question items. A sample item was “Others exclude me when they talk in the workplace.” The value of the internal consistency coefficient α was 0.821.

For affiliation-oriented OCB, Mcallister et al’s13 scale was adopted, and 5 question items were included. A sample item was “I am willing to help new colleagues adapt to their work; I am willing to help colleagues solve their problems.” The value of the internal consistency coefficient α was 0. 803.

For challenge-oriented OCB, the scale developed by Mackenzie et al54 was used, and included 5 question items. A sample item was “I am willing to express opinions that are beneficial to the company’s development even if they are denied.” The value of the internal consistency coefficient α was 0. 834.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To determine the discriminant validity among the variables in the model, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for the five models using AMOS 22.0, and the results are listed in Table 1. The fitting effect of the five-factor model was better than that of the other four models, ie, χ2/df=1.562, RMSEA = 0. 028, GFI=0.912, IFI = 0. 936, CFI = 0. 936. Each variable in the five-factor model had good discriminant validity; thus, the next analysis could be conducted.

|

Table 1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Common Method Biases Test

Harman’s one-factor test method was used to test common method bias. A total of 6 factors with eigenroots greater than 1 were extracted from the results of unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The main factor explained only 26.118% of the total variance variation; thus, no serious common method bias was initially determined.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The mean values and standard deviations of each variable and the correlation coefficients between the variables are presented in Table 2. It can be seen that the leader’s prosocial orientation shows significant positive relationships with affiliation-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (r=0.643, p<0.01), challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (r=0.532, p<0.01), and affective commitment (r=0.265, p<0.01). Affective commitment is positively related to affiliation-oriented OCB (r=0.274, p<0.01) and challenge-oriented OCB (r=0.280, p<0.01) while, affective commitment was negatively related to workplace ostracism (r=−0.172, p<0.01). It can be concluded that the analyzed results are consistent with the theoretically expected relationships, and the study hypotheses are initially proved.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis |

Hypothesis Tests

Tests for the Main Effect and Mediating Effect

The main effect and mediating effect were tested by Hierarchical regression analysis in SPSS, and the results are shown in Table 3. When gender, age, years working and educational background remain constant, the leader’s prosocial orientation shows significant positive effects on affiliation-oriented OCB (β=0. 648, p<0. 001) and challenge-oriented OCB (β=0. 521, p<0. 001). Thus, the theoretical hypotheses H1 and H2 can be verified. The leader’s prosocial orientation has significant positive effects on affective commitment (β=0. 282, p<0. 001). Introducing the mediating variable to M2, affective commitment shows a significant positive relationship with affiliation-oriented OCB (β=0. 103, p<0. 05). Meanwhile, it is still positive for the effects of leader’s prosocial orientation on affiliation-oriented OCB (β=0.619, p<0. 001). This illustrates that there is a partial mediating effect of affective commitment between leader’s prosocial orientation and affiliation-oriented OCB. Thus, hypothesis H3 is verified. Similarly, hypothesis H4 can also be proved.

|

Table 3 The Analysis Results of the Main Effect and Mediating Effect |

Moderating Effect Tests

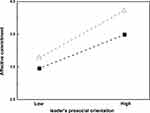

In this section, Hierarchical regression analysis was performed in SPSS based on the criteria proposed by Baron et al.55 After fixing the control variables, the independent variables, the moderating variables, and their interaction term were added into the model in turn. To exclude the adverse effects of multicollinearity on the data analysis, the leader’s prosocial orientation and workplace ostracism were centralized and used to construct the interaction term. Table 4 shows significant negative effects of the interaction term on affective commitment (β=−0. 098, p<0. 05), and hypothesis H5 can be validated. Using the two benchmarks, ie, one standard deviation above the mean value and one standard deviation below the mean value, the moderating effect analysis was performed, and the results are plotted in Figure 2. The positive effects of leader’s prosocial orientation on affective commitment gradually weaken with increasing workplace ostracism level. Workplace ostracism plays a negative moderating role in the influential relationship between leader’s prosocial orientation and affective commitment.

|

Table 4 Analysis Results of the Moderating Effect |

Moderated Mediating Effect Test

The existence of a moderated mediating effect was tested using the bootstrap method. In this study, the bootstrap sample size was set as 5000, and the confidence interval was set as 95%. The analysis results are shown in Table 5. When the perception level of workplace ostracism is low, the 95% confidence interval is [0.044, 0.227], excluding 0. Thus, the moderated mediating effect is significant. In contrast, when the perception level of workplace ostracism is high, the 95% confidence interval is [−0.016, 0.038], including 0. Thus, the moderated mediating effect is not significant. For the difference in the indirect effects between the two conditions, the confidence interval is [−0.146, −0.017], excluding 0. The relationship between the leader’s prosocial orientation and affiliation-oriented OCB illustrates that workplace ostracism significantly negatively moderates the mediating role of affective commitment. The moderated mediating effect is significantly higher under the low workplace ostracism condition than the value under the high workplace ostracism condition. Specifically, the higher the level of workplace ostracism, the weaker the mediating role of affective commitment will be. Conversely, the lower the level of workplace ostracism, the stronger the mediating role of affective commitment will be. Thus, hypothesis H6 is proved. Similarly, hypothesis H7 can also be validated.

|

Table 5 Path Analysis Results of the Moderated Mediating Effects |

Discussion

From the perspective of leadership traits, the influencing mechanisms and boundary conditions of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ OCBs are first explored. Then, a moderated mediating model is established. By analyzing the questionnaire data from the leader–employee pairs among the 347 employees of 73 teams, the following conclusions can be obtained. On the one hand, the leader’s prosocial orientation directly contributes to the promotion of affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. On the other hand, employees’ affective commitment to the organization can be promoted by the leader’s prosocial orientation. Thus, the production of affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs is indirectly promoted by the leader’s prosocial orientation. At the same time, this mediating process can be weakened by workplace ostracism. As a key organizational situation, workplace ostracism can affect the positive effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ affective commitment. In detail, the positive effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ affective commitment are weaker when the level of workplace ostracism is higher. Conversely, the positive effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ affective commitment are stronger when the level of workplace ostracism is lower.

Theoretical Implications

First, from the perspective of leadership traits, this study enriches the research on the antecedent variables for OCB to explain the formation mechanism of employees’ OCB, Derue et al4 pointed out that leadership traits are an important perspective for predicting employees’ behavior. However, most studies have investigated OCB from a behavioral perspective, and few studies have explored it from a trait perspective. From the leadership trait perspective, the leadership personality trait of leaders’ prosocial tendencies is included in this study, which verifies that leaders’ prosocial tendencies have significant positive effects on both affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. The study broadens the application of leadership trait theory in the field of organizational behavior and enriches the research related to the influencing factors of employees’ OCB. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that leaders’ prosocial tendencies are effective leadership traits in Chinese management situations and expand the explanatory boundary of the theoretical perspective for leader personality traits.

Second, based on social identity theory, affective commitment as a mediating variable is selected and introduced into the study’s theoretical model. In organizations, affective commitment characterizes employees’ feelings about organizations, which can change their behaviors in terms of intrinsic values and psychological attitudes. From the perspective of employees’ affective commitment, this study illustrates the effects of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. Moreover, the findings validate the mediating role of affective commitment. The study’s findings have theoretical implications for opening the “black box” regarding the influence process of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on OCBs. The research on the influencing mechanism of the psychological paths between leaders and employees can be thereby enriched.

Finally, workplace ostracism, as an important organizational situation, is introduced as the boundary condition in this paper. The research on the influencing mechanism of leadership traits on employees’ OCB is furthered by the current study. In general, leadership personality traits are relatively stable, external situation-independent predictors of OCB. However, due to the different individual characteristics of employees, the effectiveness of leadership influence tends to vary from person to person, which can be examined through the inclusion of moderating variables. Therefore, in the context of Chinese organizational management situation, this study examines the moderating effects of employees’ perceived levels of workplace ostracism. It also validates that workplace ostracism has a negative moderating effect on the pathway through which leaders’ prosocial tendencies influence affective commitment. Furthermore, the mediating effect of workplace ostracism on affective commitment has a significant moderating effect. By establishing a moderated mediating model, this paper studies the differences in leadership effectiveness under different workplace cold violence situations and highlights the importance of situational factors. The findings further enhance the explanatory power of the existing research framework for realistic management practices.

Management Implications

First, the results of this study show that leaders’ prosocial tendencies have positive effects on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. Therefore, in management practices, the degree of prosocial tendencies of candidates should be examined when selecting team leaders. In addition, organizations should consciously cultivate leaders’ prosocial tendencies to induce them to exhibit more prosocial behaviors and further promote the development of employees’ OCBs. From the employee perspective, the leader is the most direct representative of the organization, and the leader’s behaviors and attitudes will directly affect the feelings of employees in the organization. Therefore, leaders need to pay more attention to the effects they exert on employees. A prosocial tendency is an excellent personality trait. Leaders should improve prosociality as much as possible in their daily work and show more prosocial behaviors to enhance the positive effects on employees. Prosocial behaviors, such as timely caring for employees’ work and life, taking the initiative to provide humanitarian assistance and actively fighting for employees’ benefits, can be adopted to promote employees’ sense of belonging and identification with the organization. Employees sense of belonging and responsibility to the organization will be correspondingly promoted.56 Furthermore, leaders’ prosociality tends to implement positive behaviors that benefit the organization and thereby improve business performance.

Second, the results of this study show that affective commitment mediates the influence of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. In other words, affective commitment shows a driving effect on OCB. Therefore, in management practices, leaders should focus on creating a harmonious environment and value employees’ interests to increase their affective commitment to the organization. Furthermore, the generation of OCB among employees can be promoted. On the one hand, the organization can improve rules related to recruitment, training, promotion, reward and punishment. Appropriate practice measures of human resource management should be adopted to create a fair, just, harmonious and inclusive environment and to enhance employees’ identity perception and emotional attachment to the organization. On the other hand, leaders should pay attention to the personal interests of employees and take the initiative to help employees work better and plan for their career development. At the same time, more opportunities for job performance and autonomy should be given to employees, which can help employees recognize the organization’s attention and cultivation.57 As a result, the sense of belonging and affective attachment to the organization will be improved for employees and promote the implementation of OCB.

Last, the study finds that workplace ostracism plays a negative moderating role in the proposed model, which can inhibit the generation of OCB. Therefore, to reduce the occurrence of workplace ostracism in organizations, leaders should pay attention to the constructions of harmonious working environments and humanistic environments. In the Chinese organizational context, the ideas of “human society” and a “small circle culture” exist widely in organizations.58 Workplace ostracism is a type of performance of “small circle culture”, and it is felt by employees in organizations to mainly come from leaders and colleagues. For leadership ostracism behavior, its damaging effects obviously exceed other sources of ostracism in the workplace due to the central position and authoritative image of leaders in organizations. The main forms of leadership ostracism involve leaders treating employees differently and not handling matters fairly. When an employee in an organization notices that a leader treats other employees differently, he may imitate the leader’s behavior out of fear of authority or establish a close relationship with the leader. Furthermore, this allows leadership ostracism to be escalated and to spread within the organization. Therefore, leaders should be fully aware of the potentially damaging effects of leadership ostracism. On the one hand, organizations should have a strict and clear system of rewards and punishments to monitor leaders to handle affairs fairly to establish a harmonious, fair and just working environment. On the other hand, leaders should develop rules and a culture to improve the organization’s humanistic environment. At the same time, leaders should resolutely resist the “small circle culture” and establish effective monitoring rules to prosecute and punish the leadership ostracism phenomenon.

Research Limitations and Perspectives

The study explores only the leadership traits of leaders’ prosocial orientation, and other leadership traits can be further studied in the future. Additionally, the questionnaire data were analyzed using cross-sectional data, and future measurements can be tracked over time to reveal the dynamic relationships between the variables.

Conclusion

The results show that leaders’ prosocial tendencies have significant positive effects on both affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. Affective commitment partially mediates the relationships between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affiliation-oriented, challenge-oriented OCBs. Workplace ostracism significantly negatively moderates the relationship between leaders’ prosocial tendencies and affective commitment. Moreover, the study verified that the mediating effect of workplace ostracism on affective commitment had a significant moderating effect.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) From the perspective of leadership traits, the psychological paths and boundary conditions of leaders’ prosocial tendencies to influence OCB are explored, which provides a new perspective for studying the influencing factors of OCB. (2) From the perspective of psychology, affective commitment mediates the influence of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on affiliation-oriented and challenge-oriented OCBs. The study has theoretical implications for opening the “black box” of the influencing process of leaders’ prosocial tendencies on OCB. (3) A moderated mediating model is established by introducing an important organizational situation of workplace ostracism as the boundary condition. The study also has significant meanings for the knowledge improvement in terms of the mechanism of leadership traits on employees’ OCBs.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Committee of Ethics of Liaoning Technical University. Participation in this study was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured in this study. Before the survey, we obtained permissions from the management committees of 14 enterprises. An invitation letter appeared above the survey in which the participants were told about the purpose of the survey. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51404125.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bennett N, Lemoine J. What VUCA really means for you. Harv Bus Rev. 2014;92:

2. Arne LE, Berge MS. Viking leadership: how Norwegian transformational leadership style effects creativity and change through organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Int J Cross Cultural Manag. 2018;18(3):309–325.

3. Gupta V, Agarwal UA, Khatri N. The relationships between perceived organizational support, affective commitment, psychological contract breach, organizational citizenship behaviour and work engagement. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(3):1624.

4. Joanne CSH, Kim KOM. Antecedents of civic virtue and altruistic organizational citizenship behavior in Macau. Soc Bus Rev. 2021;16(1):113–133. doi:10.1108/SBR-06-2020-0085

5. Torlak N, Gokhan CK, Muhammet SD, Budur T. Links connecting nurses’ planned behavior, burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. J Workplace Behav Health. 2021;36(1):77–103. doi:10.1080/15555240.2020.1862675

6. Hermawan H, Thamrin HM, Priyo S. Organizational citizenship behavior and performance: the role of employee engagement. J Asian Finance Econ Bus. 2020;7(12):1089–1097. doi:10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no12.1089

7. Meniado JC. Organizational citizenship behavior and emotional intelligence of EFL teachers in Saudi Arabia: implications to teaching performance and institutional effectiveness. Arab World English J. 2020;11(4):3–14. doi:10.24093/awej/vol11no4.1

8. Ruhul A, Alamgir HM, Masud A. Job stress and organizational citizenship behavior among university teachers within Bangladesh: mediating influence of occupational commitment. Management-Poland. 2020;24(2):107–131.

9. Kang J, Ji Y, Baek W, Byon KK. Structural relationship among physical self-efficacy, psychological well-being, and organizational citizenship behavior among hotel employees: moderating effects of leisure-time physical activity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):643–652. doi:10.3390/ijerph17238856

10. Li N, Chiaburu DS, Kirkman BL. Cross-level influences of empowering leadership on citizenship behavior: organizational support climate as a double-edged sword. J Manage. 2017;43(4):1076–1102. doi:10.1177/0149206314546193

11. Vandyne L, Cummings LL, Parks JM. Extra-role behaviours: in pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). Res Organ Behav. 1995;17:215–285.

12. Choi JN. Change—oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Effects of work environment characteristics and intervening psychological processes. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(4):467–484. doi:10.1002/job.433

13. Mcallister DJ, Kamdar D, Morrison EW, Turban DB. Disentangling role perceptions: how perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(5):1200–1211. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1200

14. Li R, Zhang Z, Tian X. Can self-sacrificial leadership promote subordinate taking charge? The mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of risk aversion. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(5):758–781. doi:10.1002/job.2068

15. Foote DA, Tang T. Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Manage Decision. 2008;46:933–947. doi:10.1108/00251740810882680

16. Paulin M, Ferguson R, Bergeron J. Service climate and organizational commitment: the importance of customer linkages. J Bus Res. 2006;59(8):906–915. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.03.004

17. López-Domínguez M, Enache M, Sallan JM, Simo P. Transformational leadership as an antecedent of change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. J Bus Res. 2013;66(10):2147–2152. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.041

18. Cote S, Kraus MW, Cheng B, et al. Social power facilitates the effect of prosocial orientation on empathic accuracy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(2):217. doi:10.1037/a0023171

19. Armstrong SM, Schlosser F. Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. J Organ Behav. 2011;32(2):319–344. doi:10.1002/job.647

20. Newman A, Schwarz G, Cooper B, Sendjaya S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J Bus Ethics. 2017;145(1):49–62. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2827-6

21. Zhang Y, Xie Y. Authoritarian leadership and extra-role behaviors: a role-perception perspective. Manag Organ Rev. 2017;13(1):147–166. doi:10.1017/mor.2016.36

22. Derue DS, Nahrgang JD, Wellman NED, Humphrey SE. Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: an integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Pers Psychol. 2011;64(1):7–52. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x

23. Zhou X, Wu Z, Liang DD, et al. Nurses’ voice behaviour: the influence of humble leadership, affective commitment and job embeddedness in China. J Nurs Manag. 2021. doi:10.1111/jonm.13306

24. Phomane KP, Douglas M. Bolstering innovative work behaviours through leadership, affective commitment and organisational justice: a three-way interaction analysis. Int J Innov Sci. 2021. doi:10.1108/IJIS-10-2020-0205.ISSN:1757-2223

25. Bizri R, Wahbi M, Jardali HA. The impact of CSR best practices on job performance: the mediating roles of affective commitment and work engagement. J Organ Effect. 2021;8(1):129–148. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-01-2020-0015

26. Jessica SYH, Sanjayas SG, Kok WC, Nasreen K. Gender roles and customer organizational citizenship behaviour in emerging markets. Gender Manage. 2017;32(8):503–517. doi:10.1108/GM-01-2017-0009

27. Ansa S, Nahid R, Rauf A. The relationship between transformational leadership, prosocial behavioral intentions, and organizational performance. J Asian Finance Econ Bus. 2021;8(1):487–493.

28. Lee SY, Ito T, Kubota K, Ohtake F. Reciprocal and prosocial tendencies cultivated by childhood school experiences: school uniforms and the related economic and political factors in Japan. Int J Educ Dev. 2021;83:102396. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102396

29. Feng L, Zhang L. Prosocial tendencies and subjective well-being: the mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Soc Behav Pers. 2021;49(5):e9986. doi:10.2224/sbp.9986

30. Wu Q, Zhang X, He F. The multi-level influence of leader’s prosocial orientation on employee’s organizational citizenship behavior. Chin J Manag. 2020;17(10):1470–1477. In Chinese.

31. Grant AM, Mayer DM. Good soldiers and good actors: prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(4):900–912. doi:10.1037/a0013770

32. Cote S, Kraus MW, Cheng BH, et al. Social power facilitates the effect of prosocial orientation on empathic accuracy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(2):217–232.

33. Marcos A, García-Ael C, Topa G. The influence of work resources, demands, and organizational culture on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors of Spanish Police Officers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7607. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207607

34. Shin J, Lee BY. The effects of adolescent prosocial behavior interventions: a meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Educ Rev. 2021;1–3. doi:10.1007/s12564-021-09691-z

35. Albalawi AS, Naugton S, Elayan MB, Sleimi MT. Perceived organizational support, alternative job opportunity, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intention: a moderated-mediated model. Organizacija. 2019;52(4):310–324. doi:10.2478/orga-2019-0019

36. Qian X, Zhang M, Jiang Q. Leader humility, and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior and withdrawal behavior: exploring the mediating mechanisms of subordinates’ psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2544. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072544

37. Duarte AP, Ribeiro N, Semedo AS, Gomes DR. Authentic leadership and improved individual performance: affective commitment and individual creativity’s sequential mediation. Front Psychol. 2021;12(12):675749. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.675749

38. Simon LA, Andrew M. Personality, self-efficacy and job resources and their associations with employee engagement, affective commitment and turnover intentions. Int J Human Resource Manag. 2020;31(5):657–681. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1362660

39. Tatfur EO, Xhako D, Metin CS. The buffering effect of perceived organizational support on the relationships among workload, work–family interference, and affective commitment: a study on nurses. J Nurs Res. 2021;29(2):1–11.

40. Zhu X, Wang T. How does entrepreneur humor inspire team entrepreneurial passion? The Composite multiple mediating role of team psychological safety and team affective commitment. Econ Manag J. 2019;6:75–90. in Chinese.

41. Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Affective organizational commitment and citizenship behavior: linear and non-linear moderating effects of organizational tenure. J Vocat Behav. 2011;79(2):528–537. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.006

42. Tharikh SM, Ying CY, Saad ZM, Sukumarana K. Managing job attitudes: the roles of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behaviors. Procedia Econ Finance. 2016;35:604–611. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00074-5

43. Khalid AD, Mohammed A, Anjali B. Servant leadership and affective commitment: the role of psychological ownership and person–organization fit. Int J Organ Anal. 2020;29(2):493–511.

44. Xu J, Xie B, Chung B. Bridging the gap between affective well-being and organizational citizenship behavior: the role of work engagement and collectivist orientation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4503. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224503

45. Liu C, Cao J, Zhang P, Wu G. Investigating the relationship between work-to-family conflict, job burnout, job outcomes, and affective commitment in the construction industry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5995. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165995

46. Ferris DL, Brown DJ, Berry J, Lian H. The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(6):1348–1366. doi:10.1037/a0012743

47. Chung YW. The relationship between workplace ostracism, TMX, task interdependence, and task performance: a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4432. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124432

48. Wang B, Chen M, Qian J, Teng X, Zhang W. Workplace ostracism and feedback-seeking behavior: a resource-based perspective. Curr Psychol. 2021;1–5. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01531-y

49. Hasnawi HHA, Abbas AA. Workplace ostracism as a mediating variable in the relationship between paradoxical leader behaviours and organizational inertia. Organizacija. 2020;53(2):165–182. doi:10.2478/orga-2020-0011

50. Amer AAA, Cai Y, Amoah JA. Workplace ostracism, paranoid employees and service performance: a multilevel investigation. J Manag Psychol. 2021;36(2):121–137. doi:10.1108/JMP-01-2020-0008

51. Chen Y, Li S. The relationship between workplace ostracism and sleep quality: a mediated moderation model. Front Psychol. 2019;10:319. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00319

52. Feldman S, Steenbergen MR. The humanitarian foundation of public support for social welfare. Am J Pol Sci. 2001;45(3):658–677. doi:10.2307/2669244

53. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

54. Mackenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP. Challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors and organizational effectiveness: do challenge-oriented behaviors really have an impact on the organization’s bottom line? Pers Psychol. 2011;64(3):559–592. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01219.x

55. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;51(6):1173–1176. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

56. Arshad M, Abid G, Contreras F, Elahi NS, Ahsan AM. Impact of prosocial motivation on organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment: the mediating role of managerial support. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2021;11(2):436–449. doi:10.3390/ejihpe11020032

57. Khan GJ, Ullah KN, Muhammad K, Muhammad Y, Asfia O, Ayunni SNA. Do environmental transformational leadership predicts organizational citizenship behavior towards environment in hospitality industry: using structural equation modelling approach. Sustainability. 2021;13(10):5594. doi:10.3390/su13105594

58. Arshad M, Abid G, Torres FVC. Impact of prosocial motivation on organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating role of ethical leadership and leader–member exchange. Qual Quant. 2021;55:133–150. doi:10.1007/s11135-020-00997-5

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.