Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Employees’ Tacit Knowledge Sharing in Start-Ups: A Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Pu B , Sang W, Yang J, Ji S, Tang Z

Received 8 November 2021

Accepted for publication 2 January 2022

Published 14 January 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 137—149

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S347523

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Bo Pu,1,2,* Wenyuan Sang,2 Juan Yang,3,* Siyu Ji,2 Zhiwei Tang1

1School of Public Affairs and Administration, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Business and Tourism, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, 611830, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, 610031, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Bo Pu; Wenyuan Sang Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: This study explores the causal relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups. Construct a moderated mediation model to test the mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of career growth opportunities.

Methods: A questionnaire was used to collect data, and 485 samples of employees in Chinese start-ups were collected. Regression analysis and structural equation model were used to analyze data and verify hypotheses.

Results: The study shows that entrepreneurial leadership has a significant positive effect on employees’ affective commitment and tacit knowledge sharing. Affective commitment plays a mediating effect between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ tacit knowledge sharing. Career growth opportunities play a positive moderating role in the impact of entrepreneurial leadership on affective commitment and tacit knowledge sharing, and positively moderate the indirect effect of entrepreneurial leadership on tacit knowledge sharing through affective commitment.

Conclusion: The research illustrates that the managers of start-ups can improve employees’ affective commitment by giving full play to entrepreneurial leadership and combining the career growth opportunities provided by the organization. Employees’ tacit knowledge sharing behavior is stimulated, providing guiding value for knowledge management and the human resource management of start-ups.

Keywords: entrepreneurial leadership, tacit knowledge sharing, affective commitment, career growth opportunities

Introduction

Science and technology such as the internet promote economic growth, and emerging enterprise groups appear in the spring breeze of innovation and entrepreneurship. Since 2012, the number of Chinese enterprises registered has increased sharply.1 There were 3.159 million newly registered enterprises in China in the first three-quarters of 2015.2 According to the Hurun Global Unicorn List 2020, China ranked second globally with 227 Unicorn enterprises.3 Start-ups are “potential stocks” facing high risk and high returns. The management styles can reflect entrepreneurial spirit and have an essential impact on employees’ attitudes and behavior.4

Entrepreneurial leadership (EL) is one of managers’ more common leadership styles in start-ups. It refers to the leadership behavior that inspires subordinates by creating a vision, wins their commitment, and devotes themselves to discovering and creating strategic value.5 EL integrates the entrepreneurial spirit and leadership of the managers of start-ups and can provide new enterprises with the ability to make the necessary diversity and deal with the complex dynamic environment.6 Some studies showed that EL positively impacted organizational resilience and employee innovation behavior. However, current research still lacked in-depth exploration of the impact on employees’ knowledge management behavior.7

Tacit knowledge sharing (TKS) is one of the crucial extra-role behavior of the new generation of enterprise employees. Due to its difficult coding and transfer,8 the nature of non-role behavior, and the pressure of group competition, TKS has become the focus and difficulty of organizational knowledge management. Tacit knowledge (TK) is essential to enhancing individual competitive advantage and enterprise value.9 Zhong et al pointed out that the organization’s leadership ability, leadership style and organizational cultural atmosphere are potential factors affecting employees’ knowledge sharing (KS).10 However, existing studies have focused on the impact of transformational leadership on employees’ KS.11,12 Although EL in start-ups has played a critical role in leadership research, empirical research on the relationship between EL and TKS is limited.13 To fill this research gap, the study puts forward the first research question: Is the TKS behavior of employees in start-ups affected by EL?

Cognitive-affective personality system (CAPS) theory points out that when facing specific situational characteristics, the dynamic network structure of the personality system begins to function, and individual cognitive affective units are activated to stimulate the change of behavior units. There are many possible connections between each unit in the personality network system. Some situational features may directly activate the unit or produce explicit behavior through the activation of other units in the system. Previous studies have shown that leadership can directly affect employees’ KS and indirectly affect KS, such as organizational culture and emotional connection.14,15 Reviewing the relevant literature, few studies have investigated the mediating role of affective commitment (AC) in the study of EL of start-ups. Therefore, does employees’ AC mediate the relationship between EL and employee TKS?

Self-determination theory (SDT) pointed out that personal motivation and behavior result from the interaction between individual and external environment stimulation. As a positive information environment provided by the organization, career growth opportunities (CGO) can positively affect employees’ emotions, motivation, and behavior.15 Career development and CGO are feasible for managers to maintain and rebuild organizational commitment and affirm employees’ past work and the actual performance of organizational resource allocation.16,17 But only a few studies consider the moderating role of CGO in transformational leadership research. As a positive information environment provided by the organization, can CGO moderate the strength of the relationship between EL, AC and TKS? Does CGO moderate the mediating role of AC?

This study mainly investigates the positive influence of El on employees’ TKS from the following aspects. This paper expounds that EL positively affects employees’ TKS, then discusses the mediating role of AC, and verifies that employees’ perceived CGO positively moderate the relationship between EL and employees’ AC and TKS; finally, this paper confirms that CGO can positively moderate the indirect effect of EL on TKS through AC.

The rest of the study is organized as follows. This study begins with the theory and hypothesis development, including discussing the emergence and research vacancy of EL. Next, this study presents the research hypotheses and model, followed by a description of the research methodology. Then this paper presents the results and discussion of crucial findings. Finally, this paper discusses the implications and limitations and provides the concluding remarks in the final section.

Theory and Hypothesis Development

Entrepreneurial Leadership

Entrepreneurial leaders can cope with the complex and changeable market environment and create sustainable value, making start-ups gain advantages in new fields.18 The research on EL began in the 1940s. The concepts involved mainly include “entrepreneurship”, “entrepreneurial orientation”, and “entrepreneurial management”.19–21 Gupta et al believed that EL is a visionary scenario creation used to gather and mobilize a group of supportive participants.5 EL integrates the entrepreneurial spirit and leadership of the managers of start-ups and can provide new enterprises with an ability to deal with the complex dynamic environment.6,22

EL has gradually formed a trait and behavior perspective in its development. Gupta believed that EL includes five dimensions: building challenges, absorbing uncertainty, clearing the way, establishing commitments and clarifying restrictions. Kuratko believed that entrepreneurial leaders need to find development opportunities, take risks, point out the direction and put ideas into practice.23 As one of the general leadership styles in recent years, EL has attracted scholars’ attention on its impact on enterprise performance and employee behavior. EL is usually used as an antecedent variable to explore its implications for enterprise performance and innovation behavior.24–26 In contrast, the research on the impact of EL on the individual level in China still lacks in-depth exploration.27

Entrepreneurial Leadership and Tacit Knowledge Sharing

Entrepreneurial leader’s behavior is an important factor in the organizational context, which will undoubtedly impact employees’ in-role and extra-role behavior. As extra-role behavior of enterprise employees, TKS is the major source of improving individual competitive advantage and enterprise value.28 The research on the influence of leaders’ behavior style on TKS among organization members has attracted more and more attention. Zhang discussed the impact of self-sacrificing leadership on employees’ TKS, and the data results verified the positive promotion effect between them.29 From the moral lens, moral leadership also plays a pivotal positive role in TKS.14 But abuse and authoritarian leadership negatively affected employees’ willingness and behavior of TKS.30,31

Entrepreneurship and knowledge management have a specific internal relationship, while they focus on establishing and constructing innovation situations.32 EL has the transformative and innovative nature of transformative leadership and the high participation and incentive of team-oriented leadership to promote employees’ TKS. The continuous integration and adjustment of resources of start-ups may bring uncertainty to employees. Employees will pay more attention to the potential risks brought by their behavior, so they will be cautious in TKS.33 EL enable employees to establish self-confidence and commitment and improve employees’ loyalty and interest dependence.34 This organizational atmosphere enables employees to take a positive attitude towards TKS to achieve organizational and individual achievements. Therefore, this paper puts forward the following assumption.

H1: Entrepreneurial leadership has a positive effect on employees’ tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups.

Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

Affective commitment reflects employees’ emotional dependence and involvement in the organization and is the core dimension of organizational commitment.35 According to the CAPS, various stimuli in the corporate context will activate the cognitive affective unit of employees, and then affect employees in-role behavior and extra-role behavior.4 Transformational leadership is positively correlated with AC, while laissez-faire leadership is negatively correlated with AC.15 Authoritarian leaders reduce employees’ AC by weakening employees’ insider identity perception, and finally reduce employees’ mutual assistance behavior.4 Gupta pointed out that EL refers to the leadership behavior that inspires subordinates by winning subordinates’ commitment and devoting themselves to discovering and creating strategic value.5 Yang confirmed that entrepreneurial leaders make employees commit to strategic value creation by formulating achievable challenges, creating vision and building support.36 Based on the above, this paper proposes the following assumption.

H2: Entrepreneurial leadership positively affects employees’ AC in start-ups.

AC is the vital factor to explain employees’ extra-role behavior. When employees have high AC, they tend to show a more positive attitude and behavior, promoting employees to better complete work tasks and achieve organizational goals.37 Klein showed that employees with high AC expressed high trust in the organization, enabling internal motivation to make more positive organizational behavior.38 Study also confirmed that employees with high AC would produce a sense of responsibility in return for the organization and create more extra-role behavior.4 Akturan pointed out that the knowledge-sharing behavior of organization members was directly driven by self-worth and self-efficacy,39 and TKS was influenced by personal characteristics, motivation, resource adequacy and subjective factors expected to report. This study proposes the following hypothesis.

H3: Affective commitment of employees has a positive impact on their tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups.

Hendriks pointed out that the key to promoting KS was to enable knowledge owners to obtain some incentives.40 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the organizational support felt by employees had a positive impact on employee well-being and participation behavior, and employees’ AC mediates this relationship.41,42 Data from the medical field also confirmed that AC played a mediating role between nurses’ involvement and innovative behavior.43 Entrepreneurial leaders make the employees of start-ups emotionally satisfied utilizing authorization and incentive. Their identification with the organization and close connection with members promote positive in-role and extra-role behavior. Positive role behavior can build and maintain employees’ social network. This study proposes the following hypothesis.

H4: Affective commitment of employees plays a mediating role between entrepreneurial leadership and tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups.

Moderating Role of Career Growth Opportunities

CGO is a crucial non-economic reward, which refers to the opportunities an organization provides employees with learning, growth, and career development.44 The increase of CGO and related resources can enhance the employability and safety of employees. When an organization provides employees with proper career development planning, an effective training system, fair performance evaluation and a salary system, employees will transform perceived organizational support into dependence and AC to the organization and its members.45 The case of university teachers showed that CGO actively moderated the impact of transformational leadership on organizational commitment.17 The interaction between EL and employees’ perceived CGO may considerably impact employees’ AC. The following hypothesis was made:

H5: Career growth opportunities positively moderate the effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ affective commitment in start-ups.

CGO can induce and strengthen employees’ willingness and obligation to the organization. The research results of Bock showed that fair performance evaluation, reasonable reward procedure and practical training activities in organizations could positively affect employees’ attitudes and willingness towards KS.46 Huo believed that CGO helped employees learn professional knowledge, focus on work tasks and bring vigorous development to the organization.47 In the context of industrial upgrading and organizational change, organization members face job insecurity, such as workplace competition. Employees are usually reluctant to share TK representing core competitiveness to avoid resource loss and energy consumption.48 The improvement of employees’ employability, recognition of the organization and perception of career development and success opportunities make them willing to achieve the organization’s goals and make positive in-role and extra-role behavior. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

H6:Career growth opportunities positively moderate the effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ tacit knowledge sharing in start-ups.

As one of the crucial resources provided by the organization to individuals, CGO can effectively alleviate the exhaustion of resources such as emotional exhaustion caused by work pressure and strengthen employees’ perceived sense of organizational support and significance.49 Previous studies have confirmed that obtaining high CGO occupies a high weight in employees’ psychological contracts.50 The perception of internal growth opportunities can enhance employees’ AC, promote employees’ investment and create the performance.51 As mentioned earlier, the AC of employees in start-ups may mediate between EL and employees’ TKS, which may also be affected by the CGO perceived by employees. TKS is usually a self-conscious individual behavior of employees that is not clearly and directly defined by the organizational and compensation systems. When employees perceive higher CGO, the indirect effect of EL on employees’ TKS through AC may be stronger. Therefore, this paper put forward the following assumption.

H7: Career growth opportunities can moderate the mediating effect of affective commitment in start-ups.

The conceptual model of this paper was shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual model. |

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

A questionnaire survey was used to collect data in this study. After completing the first draft of the questionnaire, experts in relevant fields of universities and employees of start-ups were invited to give preliminary answers. According to their feedback, the language expression of the questionnaire was further modified. The formal questionnaire was collected through an online survey agency, Wenjuanxing. This study uses a two-stage survey method to reduce the influence of common method deviation. Respondents’ assessment of El, AC and personal information was completed first. In the second phase, the above respondents answered their perceived TKS and CGO in the organization. The interval between the two stages of investigation was three months. The respondents were limited to employees of start-ups in recent five years. 529 questionnaires from 62 start-ups were collected, 485 valid questionnaires were finally recovered. In terms of gender distribution, 182 men (37.53%) and 303 women (62.47%) were effective respondents. 64.53% of the respondents were between 21 and 30 years old. 77.94% had a bachelor’s degree or above in terms of education level. And 60.20% of the respondents had worked in the enterprise for 2 to 5 years.

Measures

Mature scales measured variables except for control variables. The scale was translated, retranslated and revised to form an authentic expression. The scales were measured by the Likert seven-point method, “1” means “very disagree”, and “7” means “very agree”.

Entrepreneurial Leadership

The measurement of EL adopted the scale developed by Huang6 based on the concept and dimension of EL in Gupta5 and the situation in China. The scale specifically included five dimensions: framing the challenge, absorbing uncertainty, path-clearing, building commitment and specifying limits, including 26 items such as “entrepreneurial leaders can make business decisions quickly and effectively according to the enterprise’s existing capabilities and resources”. This study took the first-order latent variable as the second-order latent variable’s index and reduced the dimension of the high-order latent variable.52,53 The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.845.

Affective Commitment

The scale of AC referred to the scale by Yao and Yang et al.36,54 This scale explored and improved the subscale of AC in the organizational commitment scale developed by Meyer and Allen55 and Ko et al.56 The items included “I’m glad to work in this enterprise”, “I feel like a part of this enterprise”, “I think working in this enterprise has a sense of belonging”, and “I have deep feelings for this enterprise”. The Cronbach’s α was 0.876.

Tacit Knowledge Sharing

TKS scale referred to the scale prepared by Bock and Tang et al.46,57 Items included “team members often share ideas and inspiration”, “team members often share each other’s work experience or know-how”, and “other team members will provide the source or insider of knowledge if requested”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.748.

Career Growth Opportunities

The measurement items of CGO referred to the CGO scale of Zhang et al.58 The items included “this enterprise provides me with the opportunities to keep up with new trends related to work”, “this enterprise provide me with the opportunities to learn new knowledge or improve professional skills”, and “this enterprise provides me with the opportunities to improve myself at work”. The Cronbach’s α was 0.810.

Control Variables

Previous studies had shown that the demographic data of enterprise employees (gender, age, education, working tenure, etc.) had a significant impact on their TKS.59 This study took employee gender, age, education and working tenure as control variables.

Statistical Analysis Program

SPSS 26.0 and Amos 24.0 were used for data processing. Firstly, confirmatory factor analysis, descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis are carried out on the samples using the above statistical software to determine whether the corresponding relationship between the measurement items meets the assumptions and expectations. Then, researchers used hierarchical regression analysis60 to test the main effect, mediating effect and moderating effect under the participation of control variables. Finally, The Bootstrapping method in the SPSS PROCESS Macro 3.361 is used to test the moderated mediation model to verify whether CGO moderates the mediating effect of AC.

Results

Measurement Model Assessment

To check the reliability and validity of constructs used in this study, three sets of necessary tests were performed: internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity,62 which were assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (α), factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) (see Table 1). The value of CR of each variable was above 0.761, Cronbach’s α falls between 0.748–0.876, all greater than 0.7. The factor loadings of each item of the variables are distributed between 0.537–0.845, which can judge that all variables have high reliability and good internal consistency. In terms of validity, the value of AVE range of the variable is 0.523–0.641, indicating that the measure term has good convergent validity.63 The square root of each variable AVE in Table 2 is greater than the correlation coefficient between variables, proving that the scale has good discriminant validity.

|

Table 1 Assessment of Measurement Model |

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between the Main Variables |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to verify the discriminant validity between core variables, mainly to test the goodness of fit of the four-factor model of EL, AC, TKS and CGO. AMOS 24.0 was used for the CFA of the model. The test results showed that the four-factor model (χ2 = 117.976, χ2/df=1.662, GFI = 0.966, AGFI = 0.941, CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.037, SRMR = 0.030) were obviously superior to other models and met the general specification requirements (χ2/df ≤ 3, GFI ≥ 0.90, AGFI ≥ 0.90, CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, SRMR ≤ 0.08).64,65 The discrimination validity of the scale was good, and there was no serious homologous deviation among the four variables.

Descriptive Statistics

Through descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis of EL, TKS, AC, CGO and control variables, the results showed that (Table 2): El was significantly positively correlated with TKS (r = 0.484, p < 0.01), AC (r = 0.549, p < 0.01) and CGO (r = 0.514, p < 0.01). TKS was positively correlated with AC (r = 0.560, p < 0.01) and CGO (r = 0.527, p < 0.01). AC was also positively correlated with CGO (r = 0.661, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis Testing

The hierarchical regression method was used to test hypothesis H1-H3. Firstly, the employees’ TKS was set as the dependent variable. Then, control variables (gender, age, education and working tenure) were added. Finally, independent variables (EL, AC, and TKS) were put into the regression equation. The test results were shown in Table 3. EL (M2, r = 0.451, p < 0.001) and AC (M3, r = 0.536, p < 0.001) had a significant positive impact on employees’ TKS in start-ups. Then employees’ AC was set as the dependent variable, and EL was set as an independent variable. AC (M6, r = 0.492, p < 0.001) had a significant positive impact on employees’ TKS. H1, H2 and H3 were verified.

|

Table 3 Hierarchical Regression Analysis Results (Main Effects) |

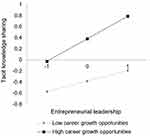

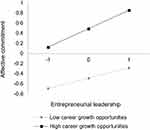

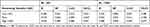

Hierarchical regression was used to test the mediating role of AC and the moderating role of CGO (see Table 4).64 The main effect test results showed that the first two conditions were verified (see Table 3). After adding the mediating variable AC, the regression coefficient of EL on employees’ TKS (M8, r = 0.254, p < 0.001) became smaller, that was, from 0.451 in M2 to 0.254 in M8. But the goodness of fit of the model became higher (M2, R2 = 0.076, M8, R2 = 0.370, ΔR2 = 0.294). It can be seen that employees’ AC played a partial mediating role between EL and employees’ TKS, H4 was confirmed. EL and CGO were centralized respectively and multiplied to obtain their interactive term Int_1. Put the control variables into the regression model and took AC and TKS as dependent variables, the interactive item Int_1 of EL and CGO had a significant positive effect on employees’ AC (M9, r = 0.108, p < 0.01), and also had a positive impact on employees’ TKS (M12, r = 0.081, p < 0.05). As shown in the moderating effect decomposition diagram in Figures 2 and 3, when the CGO were at a low level, EL had a positive effect on TKS and AC. However, the impact was lower than the effect of EL on TKS and AC when CGO were high, which also showed the positive moderating role of CGO. H5 and H6 were verified.

|

Figure 2 The moderating role of CGO between EL and TKS. |

|

Figure 3 The moderating role of CGO between EL and AC. |

Moderated Mediating Effect Test

Referring to Hayes and Scharkow’s views,66 the SPSS PROCESS Macro 3.3 was used for testing moderated mediating effects. The moderated mediating effects were analyzed by Bootstrapping method (Model 8). Bootstrap uses the repeated sampling method with the return to form a relatively stable sample combination distribution and effectively judge the overall characteristics of the sample. The confidence interval is set to 95%, and the number of Bootstrap samples is 5000. The results showed that the effect of the interaction between EL and CGO on TKS was 0.115, and the confidence interval was [0.022, 0.207], which did not include 0. The interaction effect on AC was 0.118, and the confidence interval was [0.027, 0.208], which also did not include 0. H5 and H6 were further confirmed.

Add or subtract a standard deviation to form high and low groups for CGO. Table 5 conditional indirect effects showed that the confidence intervals under high and low groups do not contain 0. For the employees of start-ups with high CGO, with the strengthening of EL, TKS behavior of employees was also increasing. And the increase rate was significantly greater than that of employees with low CGO. Using the moderated mediating effect test method, the mediation index of moderation was 0.031, and the 95% confidence interval of bootstrap was [0.004, 0.064], excluding 0. Moderated mediating effect was proved, and H7 was confirmed.

|

Table 4 Hierarchical Regression Analysis Results (Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects) |

|

Table 5 Bootstrap Test with Moderated Mediating Effect |

Conclusion

Research Results

This study discusses the positive influence of EL on employees’ TKS, clarifies the mediating effect of employees’ AC in this relationship, and defines the boundary conditions for the impact of El on TKS. This paper constructs a moderated mediation model from CAPS and SDT. The study shows that EL can directly affect employees’ willingness and behavior and indirectly affect employees’ TKS through AC. AC plays a mediating role between EL and TKS. In addition, CGO is a valuable boundary condition of the above effects, which can actively moderate the direct impact and positively moderate the mediating effect of AC. The higher EL of start-ups, the stronger AC and TKS of employees. And for employees who perceive high CGO, EL has a stronger indirect effect on TKS through AC.

Theoretical Implications

This paper answers the process and conditions of EL affecting employees’ TKS in start-ups, expands the entrepreneur leadership theory and analyzes the boundary conditions of the impact of EL on employees’ TKS in China. The study provides a new perspective on the relationship between leadership behavior traits and TKS and helps to expand the research on the influence of EL and knowledge management.

Entrepreneurial leaders can actively set opportunities situations, use limited resources to clarify the innovation development approach of enterprises.8 In this process, entrepreneurial leaders actively create an excellent organizational atmosphere and obtain the trust and follow of employees and partners.67 In previous studies, scholars pay more attention to individual and collective factors when they focus on the factors affecting the TKS intention of organizational employees. Although EL is popular in start-ups, it has been largely ignored in knowledge management research. The sustainable and healthy development of start-ups needs to pay more attention to the sharing, integration and coordination of TK among employees. EL and Chinese cultural background characteristics determine this situation: employees’ perceived emotional maintenance, self-development, relationship construction, and collective responsibility are the potential driving forces to promote employees’ TKS behavior. The empirical study of EL and employees’ TKS in Chinese start-ups showed that EL would lead enterprises to innovate and develop and play a direct and positive role in employees’ TKS.

Previous studies have pointed out that authoritarian, inclusive, and authorized leadership can promote TKS through certain factors. However, knowledge management of start-ups has not received sufficient attention. If the enterprise vision, organizational culture, and values brought by EL meet employees’ expectations, employees will have a positive emotion towards the organization.68 Emotional information often induces TKS.69 Enterprises in start-ups often need employees to have a sense of work mission and produce a spiritual experience sharing a common destiny with the enterprise.70 Under this psychological tendency and spiritual experience, employees were often willing to make positive in-role and extra-role behavior for the organizational interests. As an essential extra-role behavior, TKS will be affected by objective factors such as organizational cultural environment and sharing objects and subjective factors such as personal characteristics and resource adequacy.71 The research confirms that EL can indirectly affect employees’ TKS by affecting employees’ AC, which provides a new perspective for the impact of corporate leadership style on TKS.

CGO helps enhance employees’ employability, loyalty and recognition to the organization. Under certain circumstances, employees who perceive more CGO will be more likely to rely on and affirm the organization and be more inclined to carry out positive behavior. The case of employees of start-ups in China proved that CGO had a positive moderating effect on the impact of EL on employees’ AC and TKS. This is somewhat different from previous studies. Zhou and Xin pointed out that if individuals with new career orientation perceive more CGO, their employability will get a significant commission. Still, they will not produce higher AC.72 Briscoe and Finkelstein also pointed out that CGO cannot moderate the relationship between career orientation and AC.73 The research object of this study is the employees of start-ups in China, most of whom are in the early stages of their careers. Positive work experience and career development trends are very attractive to employees.74 The characteristics of “relationship” and “Ren Qing” in Chinese traditional culture and the principle of reciprocity also play a significant role.

Previous studies focused on the boundary conditions of the main effect in the study of organizational behavior. For example, CGO negatively moderates the relationship between happiness orientation and turnover intention,75 and positively moderate the relationship between employees’ psychological capital and job investment.76 Few researchers consider that the mediating role in the study of organizational behavior may also have boundary conditions. This study confirmed that employees’ perception of CGO moderated the mediating role of employees’ AC in EL and TKS. For employees with high CGO, their organizational behavior is more vulnerable to individual factors compared with the impact of organizational environmental factors. In this study, when the EL of start-ups is significant and effective, employees with high CGO are more likely to affect their TKS behavior and willingness through AC, and their TKS is significantly higher than that of employees with low CGO. The research confirms the boundary conditions of the main effect and mediating effect of knowledge management in start-ups. It provides a complete theoretical support for better explaining the behavior of employees in start-ups.

Managerial Implications

The development and application of big data, the internet and other technologies have provided good soil for Chinese innovative enterprises, and Chinese start-ups have mushroomed rapidly. This study has certain managerial implications for start-ups in employee TK management.

Start-ups should pay attention to professional cognition, ability, and leadership and management style in management recruitment and post promotion. Leadership development and training in start-ups are also necessary. Enterprises can regularly hold relevant training courses and experience sharing meetings to cultivate entrepreneurial leaders.

The commitment view under the social exchange theory shows that employees’ perceived sense of support from the organization will make them obligatory to the employer,77 and TKS as a positive employee behavior will continue to occur. Start-ups should emphasize the construction of organizational atmosphere to improve the effectiveness and interest connection between employees and organizations through certain performance appraisal and promotion systems, and finally, make TKS become the normal behavior of employees.

Compared with economic remuneration, employees pay more and more attention to long-term employability, such as promotion and development.49 Employees feel that the CGO provided by the organization can give them a sense of career security and stability. Organization managers or leaders should pay attention to guiding employees to make career planning, reasonably arrange work tasks for employees, and provide them with career guidance and training. Their perceived CGO can stimulate employees’ TKS in multiple ways to achieve start-ups’ sustainable development and performance improvement.

Limits and Prospects

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, this study discussed the factors affecting the TKS of employees in start-ups from the organizational level (entrepreneur leadership) and individual level (AC and CGO). But TKS behavior is often affected by multiple factors, such as team atmosphere,78 working environment,40 innovation pursuit,79 and reciprocal relationship.46 The above variables can be added to knowledge management research to explore their role and utility. Second, EL is a multi-dimensional variable. The study focuses on the overall situation of variables without considering the internal relationship between various dimensions. Later research can consider the effect and internal relationship of different dimensions of EL. Finally, cross-sectional data were used in the study. Although the two-stage method was used to collect the questionnaires, it was still inevitable that it could not explain the continuity and variability of individual development. The interview, experiment and follow-up investigation methods can be used to research EL and TKS in the future.

Ethical Approval

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. All the procedures were approved by the ethical committee of the School of Business and Tourism, Sichuan Agricultural University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the article editor and reviewers for their thoughtful comments that greatly improved the article. Bo Pu and Juan Yang are co-first authors for this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71804119) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M663482).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. China Central Government Portal [homepage on the Internet]. The growth rate of the number of start-ups ranks first globally, and the hope of reengineering China’s talent and economy; 2015. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-12/14/content_5023515.htm.

2. China Central Government Portal [homepage on the Internet]. There are more than 10000 newly registered enterprises every day, and the number of Chinese start-ups is the world leader; 2015. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-12/15/content_5024394.htm?gs_ws=tsina_635857979203970855.

3. Huren Report [homepage on the Internet]. Suzhou new district-Hurun global unicorn index 2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.hurun.net/zh-CN/Rank/HsRankDetails?pagetype=unicorn.

4. Leiblein MJ, Reuer JJ. Building a foreign sales base: the roles of capabilities and alliances for entrepreneurial firms. J Bus Ventur. 2004;19(2):147–307. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00031-4

5. Gupta V, MacMillan IC, Surie G. Entrepreneurial leadership: developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. J Bus Ventur. 2004;19(2):241–260. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00040-5

6. Huang S, Ding D, Chen Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and performance in Chinese new ventures: a moderated mediation model of exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and environmental dynamism. Creativity Innov Manag. 2014;23(4):453–471.

7. Desouza KC. Strategic contributions of game rooms to knowledge management: some prelimenary insights. Info Manag. 2004;41(1):63–74. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00027-2

8. Nonaka I, Takeuchi H. The knowledge-creating company. Harv Bus Rev. 1991;69(6):96–104.

9. Le PB, Lei H. Fostering knowledge sharing behaviors through ethical leadership practice: the mediating roles of disclosure-based trust and reliance-based trust in leadership. Knowl Manag Res Pract. 2018;16(2):183–195. doi:10.1080/14778238.2018.1445426

10. Zhong X, Fu Y, Wang T. Inclusive leadership, insider identity cognition and employee knowledge sharing: the moderating role of organizational innovation atmosphere. Res Dev Manag. 2019;31(03):109–120.

11. Wu WL, Lee YC. Empowering group leaders encourages knowledge sharing: integrating the social exchange theory and positive organizational behavior perspective. J Knowl Manag. 2017;21(2):474–491. doi:10.1108/JKM-08-2016-0318

12. Le PB, Lei H. The mediating role of trust in stimulating the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing processes. J Knowl Manag. 2018;22(3):521–537. doi:10.1108/JKM-10-2016-0463

13. Latif KF, Nazeer A, Shahzad F, Ullah M, Sahibzada UF, Sahibzada UF. Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on project success: mediating role of knowledge management processes. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2020;41(2):237–256. doi:10.1108/LODJ-07-2019-0323

14. Lei H, Do NK, Le PB. Arousing a positive climate for knowledge sharing through moral lens: the mediating roles of knowledge-centered and collaborative culture. J Knowl Manag. 2019;23(8):1586–1604. doi:10.1108/JKM-04-2019-0201

15. Jackson TA, Meyer JP, Wang XH. Leadership, commitment, and culture: a meta-analysis. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2013;20(1):84–106. doi:10.1177/1548051812466919

16. Weng Q, Mcelroy JC, Morrow PC, Liu R. The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(3):391–400. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.05.003

17. Bashir MS, Haider S, Asadullah MA, Ahmed M, Sajjad M. Moderated mediation between transformational leadership and organizational commitment: the role of procedural justice and career growth opportunities. SAGE Open. 2020;10(2):1–19. doi:10.1177/2158244020933336

18. Ghoshal S, Bartlett CH. Rebuilding behavioral context: a blueprint for corporate renewal. Sloan Manage Rev. 1996;37(2):23–36.

19. Wei J, Xiong R, Hassan M, Mohamd SA, Fawzi AF, Khader JA. Entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibilities, and innovation impact on banks’ financial performance. Front Psychol. 2021;12:680661. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680661

20. Miller D. The Correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manage Sci. 1983;29(7):770–791. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

21. Hameed I, Ali B. Impact of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial management and environmental dynamism on firm’s financial performance. J Econ Behav Stud. 2011;3(2):101–114. doi:10.22610/jebs.v3i2.260

22. Renko M, Tarabishy AE, Carsrud AL, Brännback M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J Small Bus Manag. 2015;53(1):54–74. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12086

23. Kuratko DF. Entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century: guest editor’s perspective. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2007;13(4):1–11. doi:10.1177/10717919070130040201

24. Rehman KU, Aslam F, Mata MN, et al. Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on product innovation performance: intervening effect of absorptive capacity, intra-firm networks, and design thinking. Sustainability. 2021;13(13):7054. doi:10.3390/su13137054

25. Shahid MM, Zhang J, Gul GF. Entrepreneurial leadership and employee innovative behavior: intervening role of creative self-efficacy. Human Syst Manag. 2020;39(3):367–379. doi:10.3233/HSM-190783

26. Yang J, Pu B, Guan Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and turnover intention of employees: the role of affective commitment and person-job fit. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(13):2380. doi:10.3390/ijerph16132380

27. Ke JL, Ding Q. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ attitude and innovation performance in start-ups: the mediating effect of workplace spirit and leader member exchange moderating effect. Econ Manag Res. 2020;41(01):91–103.

28. Li C, Makhdoom HUR, Asim S. Impact of entrepreneurial leadership on innovative work behavior: examining mediation and moderation mechanisms. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:105–118. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S236876

29. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Yao N. The impact of self-sacrificing leadership on employees’ tacit knowledge sharing. Leadersh Sci. 2017;2007(32):40–43.

30. Li Y, Zhang J, Liu Q. Research on the impact of abuse management on employees’ tacit knowledge sharing: mediated by psychological capital. Finan Account Commun. 2018;21:125–128.

31. Chen ZJ, Davison RM, Mao JY, Wang ZH. When and how authoritarian leadership and leader Renqing orientation influence tacit knowledge sharing intentions. Info Manag. 2018;55:840–849. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.03.011

32. Bandera C, Keshtkar F, Bartolacci MR, Neerudu S, Passerini K. Knowledge management and the entrepreneur: insights from Ikujiro Nonaka’s Dynamic Knowledge Creation model (SECI). Int J Innov Stud. 2017;1(3):163–174. doi:10.1016/j.ijis.2017.10.005

33. Liu B, Zhao J, Yu SX. Influence of goal orientation on tacit knowledge sharing of new generation employees: a moderated mediation model. Finance Econ. 2020;2020(02):83–93.

34. Crespo CF, Crespo NF, Curado C. The effects of subsidiary’s leadership and entrepreneurship on international marketing knowledge transfer and new product development. Int Bus Rev. 2021;(10):101928. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101928

35. Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Manag Rev. 1991;1(1):61–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

36. Yang J, Pu B, Guan Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and turnover intention in startups: mediating roles of employees’ job embeddedness, job satisfaction and affective commitment. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):1101. doi:10.3390/su11041101

37. Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442–1465.

38. Klein HJ, Molloy JC, Brinsfield CT. Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Acad Manag Rev. 2012;37(1):130–151.

39. Akturan A, Çekmecelioğlu HG. The Effects of knowledge sharing and organizational citizenship behaviors on creative behaviors in educational institutions. Procedia Social Behav Sci. 2016;235:342–350. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.11.042

40. Hendriks P. Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge sharing. Knowl Process Manag. 1999;6(2):91–100. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1441(199906)6:2<91::AID-KPM54>3.0.CO;2-M

41. Mihalache M, Mihalache OR. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum Resour Manage. 2021;(6):1–20. doi:10.1002/hrm.22082

42. Alshaabani A, Naz F, Magda R, Rudnák I. Impact of perceived organizational support on OCB in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary: employee engagement and affective commitment as mediators. Sustainability. 2021;13(14):7800. doi:10.3390/su13147800

43. Renkema M, Leede JD, Zyl L. High-involvement HRM and innovative behavior: the mediating roles of nursing staff’s autonomy and affective commitment. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29:2499–2514. doi:10.1111/jonm.13390

44. Veldhoven MV, Meijman TF. The Measurement of Psychosocial Strain at Work: The Questionnaire Experience and Evaluation of Work. Amsterdam: NIA (in Dutch); 1994.

45. Yan L, Bai S. High-performance work system and employee innovation behavior: influence from personal perception. Sci Technol Progr Countermeasures. 2016;33(20):134–139.

46. Bock GW, Zmud RW, Kim YG, Lee GN. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. Mis Quarter. 2005;29(1):87–111. doi:10.2307/25148669

47. Huo ML. Career growth opportunities, thriving at work and career outcomes: can COVID-19 anxiety make a difference? J Hospital Tour Manag. 2021;48:174–181. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.007

48. Min R, He J. Analysis of knowledge sharing based on leadership quality and employee status. Econ Jingwei. 2011;04:121–125.

49. Wang Y, Qiao M. Study on the impact of delayed job satisfaction on employee overwork: the moderating role of career growth opportunities. Western Forum. 2018;28(01):109–117.

50. Rousseau DM. New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: a study of psychological contracts. J Organ Behav. 1990;11(5):389–400. doi:10.1002/job.4030110506

51. Wang J, Han XN. Firmness and wavering: a study on the professional commitment of journalists and its influencing factors. Int Press. 2020;310(08):66–87.

52. Robert CM, Michael WB, Hazuki MS. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

53. Wu Y, Wen ZL. Topic packaging strategy in structural equation modelling. Adv Psychol Sci. 2011;19(12):1859–1867.

54. Yao T, Huang W, Fan X. Research on employee loyalty in service industry based on organizational commitment mechanism. Manage World. 2008;05:

55. Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(4):538–551. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

56. Ko JW, Price JL, Mueller CW. Assessment of Meyer and Allen’s three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(6):961–973. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.961

57. Tang C, Ai S, Gong Z. The social function of positive emotion and its impact on Team Creativity: the mediating role of tacit knowledge sharing. Nankai Bus Rev. 2011;14(04):129–137.

58. Zhang M, Zhang D. An Empirical Study on the moderating effect of value variables in Price-Mueller turnover model. Manage Rev. 2006;9:46–51.

59. Iqbal S, Toulson P, Tweed D. Employees as performers in knowledge intensive firms: role of knowledge sharing. Int J Manpow. 2015;36(7):1072–1094. doi:10.1108/IJM-10-2013-0241

60. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator- mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

61. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. NY: the Guilford Press; 2013.

62. Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Market Theory Pract. 2011;19(2):139–152. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

63. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Market Res. 1981;18(3):382–388. doi:10.1177/002224378101800313

64. Maccallum RC, Hong S. Power analysis in covariance structure modelling using GFI and AGFI. Multivariate Behav Res. 1997;32(2):193–210. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3202_5

65. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

66. Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br J Mathe Statis Psychol. 2014;67(3):450–472. doi:10.1111/bmsp.12028

67. Zhao SJ, Yi LF, Lian YL. Entrepreneurial leadership, organizational resilience and entrepreneurial performance. Foreign Econ Manag. 2021;43(03):42–56.

68. Ma F, Kong F, Sun H. Review of organizational commitment theory. Info Sci. 2010;28(11):1741–1745.

69. Benaraba C, Bulaon N, Escosio S, Narvaez A, Suinan A, Roma M. A comparative analysis on the career perceptions of tourism management students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Journal of Hospitality, Leisure. Sport Tour Educ. 2021;30:100361.

70. Xie B, Xin X, Zhou W. Sense of mission: a recovering research topic. Prog Psychol Sci. 2016;2016(5):783–793.

71. Yang H. Research on the construction of tacit knowledge sharing in informal organizations within enterprises. Info Theory Pract. 2012;35(07):

72. Zhou W, Xin X. Does the career orientation of borderless consciousness, and self-guidance improve or reduce employees’ organizational loyalty: intermediary and regulation of employability and career growth opportunities? Manag Sci. 2013;2013(09):5–20.

73. Briscoe JP, Finkelstein LM. The “new career” and organizational commitment: do boundaryless and protean attitudes make a difference? Career Dev Int. 2009;14(3):242–260. doi:10.1108/13620430910966424

74. Weng Q, McElroy JC. Organizational career growth. Affect Occup Commit Turnover Intent. 2012;80(2):256–265.

75. Rasheed MI, Okumus F, Weng Q, Hameed Z, Nawaz MS. Career adaptability and employee turnover intentions: the role of perceived career opportunities and orientation to happiness in the hospitality industry. J Hospital Tour Manag. 2020;44:98–107. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.006

76. Guo Z, Xie B, Cheng Y. How to improve the work input of knowledge workers: based on the dual perspective of resource conservation theory and social exchange theory. Econ Manag. 2016;38(02):81–90.

77. Shore LM, Wayne SJ. Commitment and employee behavior: comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(5):774–780. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.774

78. Dong P, Liu J, Wei H, Ma X. The influence of inclusive leadership on nurses’ sense of organizational support and tacit knowledge sharing. Nurs Res. 2018;32(06):938–940.

79. Zhao SS. Research on the motivation model of employee knowledge sharing under Chinese culture background. Nankai Bus Rev. 2013;16(05):26–37.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.