Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

The Effect of Contact with a Horse During a Three-day Hippotherapy Session on Physiotherapy Students' Emotions

Authors Choińska AM , Bajer W , Żurek A , Gieysztor E

Received 28 September 2021

Accepted for publication 8 April 2022

Published 3 June 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1385—1396

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S332046

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Anna Maria Choińska,1,2 Weronika Bajer,1 Alina Żurek,3 Ewa Gieysztor1,2

1Department of Physiotherapy, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland; 2SKN15 Child and Adolescent Developmental Disorders, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland; 3Institute of Psychology, University of Wroclaw, Wroclaw, Poland

Correspondence: Ewa Gieysztor, Department of Physiotherapy, Wroclaw Medical University, Ul. Grunwaldzka 2, Wrocław, 50-355, Poland, Email [email protected]

Background: Activities with horses cause many emotional reactions in their recipients, the measurement and analysis of which can provide information about positive or negative attitudes toward hippotherapy activities. The purpose of the study was to explore how horse contact affects the emotions of female and male students experiencing horseback riding during a three-day hippotherapy session.

Material and Methods: The study included 252 physiotherapy students from the Medical University of Wrocław who participated in hippotherapy classes during a three-day didactic and scientific course implemented in the years 2014–2019. The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) and the Sanoquell automatic 766 pulse measuring device were used for the study. The SPANE took place at the beginning (study I) and at the end (study II) of the camp. Pulse was measured daily before and after hippotherapy (6 times).

Results: Analysis of variance proved the existence of statistically significant difference between the intensity of positive feelings (SPANE-P, p=0.000) and negative feelings (SPANE-N, p=0.000) and in the outcome of overall satisfaction/happiness balance (SPANE-B, p=0.000) in I and II study in the group of women. No such difference was noted for the men. The pulse in women measured on the third day was statistically significantly higher than in men (p=0.0345).

Conclusion: Hippotherapy classes bring physiotherapy students an increase in positive feelings and a decrease in negative feelings. Personal experience seems to be the best way to understand and consciously use hippotherapy as a therapeutic method.

Keywords: hippotherapy classes, the positive and negative, emotions, physiotherapy students

Background

Hippotherapy (HPT) is a term that comes from the Greek words “hippos” (horse), “hippike” (the art of riding) and therapy. According to the canons of Polish hippotherapy developed by the Polish Hippotherapeutic Association, HPT is defined as a targeted therapeutic activity aimed at improving human functioning in physical, emotional, cognitive and/or social spheres, during which a specially prepared horse is an integral part of the therapeutic process.1

One of the purposes of HPT is to transmit the three-dimensional movements of a horse to the patient on horseback through rhythmic impulses. The movement of the patient’s pelvis is repetitive, it follows a certain pattern and rhythm and involves rocking (elevation and decrease), rotational (anteversion and retroversion) and lateral motions that are similar to those of a person walking. This three-dimensional movement in all planes of the pelvis, which is transmitted to the entire body through the patient’s spine, stimulates proprioception reactions and thus improves postural balance and back straightening.2 Another effect of the sensory input involved in HPT is the improvement of postural control and motor responses.3

The primary activity of HPT sessions consists in a patient sitting on horseback performing specific tasks assigned by a qualified therapist. At the same time, a second person (instructor/tutor) who knows the horse, guides the horse and controls its behavior while performing each exercise. During exercise, the horse is in motion and the therapist determines its gait pace and direction.2 Equally important in HPT is the patient’s work with the horse from the ground - cleaning, leading the horse in hand, feeding, stroking, cuddling to the horse, and messages conveyed verbally and nonverbally - body language through which the patient expresses his/her emotions.4 The effects of HPT result from the patient’s contact with a live animal in a natural environment. The special influence of HPT on the human psyche is connected to the unique sensitivity of horses developed in the course of evolution. Horses have the ability to read subtle signals that come from the environment, which is fundamental in human-horse nonverbal communication. Horses enjoy interacting with humans5 and can also read human emotions, as showed in the study by Smith et al.6 Smith et al were the first to provide evidence of horses’ ability to actively read human facial expressions in photographs and differentiate between positive (happy) and negative (angry) expressions. There are also known results that olfaction might contribute to the human recognition of horse emotions.7 Nevertheless, the relationships formed between riders and horses can help improve emotional well-being, self-confidence, self-esteem and self-awareness of riders.8 While little research can be located on the psychological benefits of students participating in hippotherapy courses,1,9 there are many studies examining the benefits of students engaging in service-learning experiences10,11 and departmental physical activity courses involving some form of practicum experience.12,13 A study by Eyler et al14 reported that service-learning activities have a positive effect on students’ personal development such as personal identity, spiritual growth, and moral development. Adapted faculty physical activity courses and service-learning courses generally include some form of practicum experiences and are the experiential education where learning occurs through a process of alternating occurring activities and reflection. At the same time, students reflect on their experience in an effort to achieve a deeper understanding of an activity, such as HPT, and a skill for themselves.

In this study, we attempted to answer the question of how contact with a horse during a practical HPT class affects the positive and negative emotions of physiotherapy students, during university classes. We believe that confronting one’s own emotions before and after horseback riding gives students, as future potential therapists, a chance to get closer to the patient’s emotional situation during HPT. In other words, the goal of the 3-day course is for students to experience this type of therapy before they start recommending it to patients. Thus, the objective of the study was to explore how horse contact affects the emotions of female and male students experiencing it during three-day hippotherapy classes.

The presented study is the result of a research project from 2014 to 2019 carried out in cooperation with the Department of Physiotherapy of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Medical University of Wrocław and the Institute of Psychology of the University of Wrocław. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The work was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University in Wrocław (KB- 796/2017).

Materials and Methods

Participants

A total of 252 students (191 females and 61 males) participated in the study, with a mean age of 23 years. Detailed information about the number of students participating in the course in subsequent years of the project is provided in Table 1. Data were collected during three-day HPT sessions for the following 6 years from 2014 to 2019. All course participants consented to participate in the study. They were briefed on the objective and the measurement methods prior to the study.

|

Table 1 Mean Age of Surveyed Physiotherapy Students (n=252) During the 3-Day Turnaround in 2014–2019 |

HPT Course Description

Physiotherapy students of the Medical University of Wrocław stayed at a three-day scientific and didactic camp organized as part of the course “Special methods in hippotherapy” and as part of the activities of the Student Scientific Group SKN15 Child and Adolescent Development Disorders, of which the first author is a supervisor. (Figure 1, SKN 15 logo).

|

Figure 1 Logo of the Student Association of Child and Adolescent Development Disorders at the Department of Physiotherapy of Medical University of Wrocław. |

The course was 30 hours long, delivered over three days, with students participating in lecture and hands-on activities on each day. During the course, students performed such activities: as the horse from the pasture and the stables to the horse cleaning station, caring for the course- preparing the horse for riding (putting on a vaulting belt or saddle and bridle), exercising with it while standing on the ground and while riding on horseback at a trot as well as watering and feeding it and cleaning the stables.

Classes were held in Dąbrówka Łubniańska in the stable “Kalinówka” where there is a predominance of Silesian horses. Exercises with students were led by a riding instructor and hippotherapist (first author). The aim of the course was substantive and practical (through active horse riding) familiarization of the student with the essence of HPT, as one of the methods supporting physiotherapy. The classes included balance, vestibular system, coordination, deep sensation, body schema, lateralization, and superficial sensation exercises. The duration of a single session on horseback was 60 minutes.

Measurement Methods

Emotional Reactions

The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE), in a Polish adaptation based on the version of the SPANE by Diener et al.15 It is a short 12-adjective scale that describes human feelings, including 6 UP pleasant feelings and 6 UN unpleasant feelings. Each SPANE item is rated on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means “very rarely or never” and 5 means “very often or always.” The scales in the positive and negative parts are scored separately due to the partial independence or separability of these two types of feelings. The total score for both SPANE-P and SPANE-N can range from 6 to 30 points. These two scores can be combined by subtracting the SPANE-N score from the SPANE-P score, and the resulting SPANE-B (happiness balance) scores can range from −24 to 24. SPANE-B is shown in Table 2. Finally, determining the “happiness balance” involves translating the score into a 7-point scale (the higher the value, the better the student performed on the happiness balance).15 SPANE-B was defined as the subjective well-being (SWB).9 Emotional response surveys took place twice, on the first day of camp before the start of practical activities (Study I) and on the third day of camp after the end of practical activities (Study II).

|

Table 2 SPANE-B; “Balance of Happiness” |

The usefulness of the SPANE scale has been confirmed in many studies.15–19 The two-factor SPANE model has been validated in several countries using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the evidence supporting the assumption of its greater universality was shown. In Latin America, validation studies have been conducted in Peru20 and Chile.21 Other western countries in which SPANE has been validated are Portugal,22 Canada,23 Serbia,24 Turkey,25 Germany,26 and Italy.27 Validation studies were also performed in Asian countries, such as China,28 Japan,29 and India.30 Cronbach's Alpha coefficients are satisfactory and are for SPANE-N 0.81, for SPANE-P 0.87, and for SPANE-B 0.89.15

Physiological Responses

Students’ heart rates were measured with a Sanoquell automatic 766 immediately before riding the horse and immediately after dismounting each day - A total of 6 times over three days. The class was held in the morning. Pulse testing was done 6 times, before getting on and after getting off the horse, each day.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software (v. 13.3 ed). The study was analysed using Wilcoxon test, Mann–Whitney U-Test and ANOVA test. The mean values (X) and standard deviations (SD) were statistically analysed.

Additionally, the Mann–Whitney U-Test and ANOVA factor analysis was conducted to assess the significance of differences in outcomes, considering separately N valid sessions of women and men. Finally, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of changes in outcomes across the group when pre and post-intervention measurements were considered.

Results

At the hippotherapy course, where the physiotherapy students themselves had the opportunity to experience both pleasant and unpleasant feelings, they were able to experience what future patients are likely to feel during therapy on horseback and experience the emotions associated with riding a horse themselves. The following results were obtained from the studies carried out:

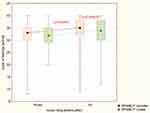

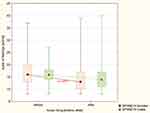

- Both male and female students frequently experienced pleasant feelings (SPANE-P) and rarely experienced unpleasant feelings (SPANE-N) before they started exercising on the horse, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, and Tables 3 and 4. Compared to the first day of the HPT class (SPANE-P1), the frequency of pleasant sensations increased on the third day in women after dismounting from the horse (SPANE-P2) p=0.0000 (Figure 2), and decreased unpleasant feelings (SPANE-N) p=0.0000, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were observed in men, positive and negative emotions in men remained constant, both on the first and third day of the turn (Figures 2 and 3, Table 4). Therefore, only a statistically significant increase in positive emotion (SPANE-P) was observed in females, compared to males, on the third day during the HPT course. The difference between men and women of positive feelings (SPANE-P2) was statistically significant at p=0.044629, while the reduction in negative feelings in both men and women followed a similar pattern as shown in Figure 2 and Table 5.

|

Table 3 SPANE-P, SPANE-N, SPANE-B- Women (N=191) - Positive and Negative Feelings on the First and Third Day of Hippotherapy in Female Students During a Three-Day Turn of Hippotherapy |

|

Table 4 SPANE-P, SPANE-N, SPANE-B-u Males (N=61) - Positive and Negative Feelings Before and After Hippotherapy in Male Students During a Three-Day Turn of Hippotherapy |

|

Figure 2 Positive feelings before (SPANE-P1) and after (SPANE-P2) 3-day’s hippotherapy session. Notes: Mann–Whitney test (with correction for continuity) for the variable: gender, p<0.05000. |

|

Figure 3 Negative feelings before (SPANE-N1) and after (SPANE-N2) 3-day’s hippotherapy session. Notes: Mann–Whitney test (with correction for continuity) for the variable: gender, p<0.05000. |

|

Figure 4 Balance of happiness of men and women before (SPANE-B1) and after (SPANE-B2) hippotherapy. Notes: Mann–Whitney test (with correction for continuity) for the variable: gender, p<0.05000. |

Discussion

The presented research shows that the psychological effect of students’ participation in hippotherapeutic activities is positive. After three days of contact with the horse, the level of pleasant feelings increases, while the level of unpleasant feelings decreases. Similarly, the overall satisfaction with the course, as indicated by the so-called SPANE-B happiness balance obtained from the Emotional Well-being Scale (SPANE), ranks high both before and after the course, especially in women.

A review of the literature shows that patients’ emotional reactions during close contact with a horse vary.

For some, there is a sense of danger that comes from the height of the horse as well as its movement through space. The basis of HPT is the selection of a suitable horse in terms of its height and temperament. An important part of the exercise is for the patient to get to know the horse by cleaning, stroking, feeding and talking. In addition, horseback riding, for most patients, offers the possibility of independent movement without the help of a carer or orthopaedic supplies. The experience of such success strengthens the patient’s self-esteem, contributes to improved motivation to make efforts and encourages increasing independence.31

Because of the expected psychological effects of HPT, its value as a method of supporting the patient’s emotional and social development is emphasised. According to Choińska et al, HPT helps the patient to cope with their feelings, ie to increase their awareness, by expressing (ie relieving) and controlling them.1

Tilešová-Rychlewska in her book states that a horse gives a sense of boundaries but also the possibility to experience consequences - positive and negative. The horse corrects our behaviour and gives a sense of I can, I am able, I can do it, i.e. it triggers positive feelings.31 The research conducted by Earles et al shows that equine therapy can be an effective treatment for symptoms of anxiety and post-traumatic stress.32 Analysis of the statements of patients participating in the study conducted by Kern-Godal et al33 showed that contact with the horse is related to the emotional effect of the therapy received. Patients experienced a sense of well-being, feelings of calm, and increased self-awareness.

According to Strauß34 and Choińska et al,9 therapeutic horseback riding influences the development of our senses through the formation of the sensory integration process, developing the perception of body schema, balance (vestibular system), coordination, deep sensation (sensation from the muscle joints and fascia) and superficial sensation (temperature, pain and touch), combined with visual, auditory and taste perception. This is done by changing the pace, and direction of movement in the horse’s space.

Our study of a HPT session with students has shown an increase in emotion and heart rate. Similar observations were made by Cabbidu et al35 who observed an increase in heart rate variability (HRV) sinus rhythm complexity compared to baseline values during HPT. The authors of the Brazilian study suggested that this increase may affect vagus nerve activation. This in turn may be an explanation for the tendency to experience positive emotions during and after HPT, as reported by the patients. The regulatory mechanism of our participants responded positively to HPT induced disruption. Cabiddu et al concluded that HPT can be beneficial to children with development disorders of neurological nature. Such disorders involve the autonomic nervous system which is stimulated during HPT.35

To date, there is little research on the psychological effects of horse contact conducted in groups of potential therapists such as physical therapy students. A study conducted by Choińska et al on physiotherapy students participating in HPT classes in 2011 found that the level of stress measured by the diagnostic synthetic function ZPS according to Krefft is statistically significantly higher in men than in women, both immediately before and immediately after horseback riding (p<0.005).9

On the other hand, the presented research shows that the intensity of pleasant feelings, and thus the positive well-being of the students increases after the hippotherapeutic course. Similar results were obtained by Buswell and Leriou11 in a study in which students reported psychological benefits from their service-learning experience in HPT, experience such as high levels of personal gratification and satisfaction, self-esteem, self-worth, and confidence. It led students to report they would like to participate in similar activities in the future, and they would recommend similar out of lecture portion of the classes to other students. Smith36 in his research on social work students, listed the student community as the primary place for practical experiences and learning about HPT and therapeutic driving. Additionally, Little and Harris37 and Astin and Sax38 reported statistically significant improvements in areas related to academic achievement for instance motivation, competence, educational aspirations, test scores, civic responsibility and life skills by service-learning participating.

The results presented in this paper were produced in a project that aimed to document the psychological benefits for students to participate in practical HPT activities. Hopefully, the results presented will encourage the enrichment of Master's degree courses with equine activities. During HPT classes, which involve direct contact between a person and a horse, participants experience positive emotions that are in harmony with nature, which enhances the attractiveness of the therapy. A study by Buswell and Leriou11 found that service-learning HPT experiences can be rewarding and inspiring. Our study examined the impact of three-day HPT classes on participants' emotions and confirmed the conclusions about the psychological benefits of contacting students with a horse. We believe that these types of classes/practicums offer students the opportunity to learn new skills and a deeper understanding of HPT, and provide a real-world experience beyond the typical classroom where many students of therapy preparation programs participate. Choosing practicums outside of regular theoretical classes allows students to gain experience in settings that will be more applicable to their future employment.

Conclusions

HPT exercises bring the physiotherapy students an increase in pleasant feelings and a decrease in unpleasant feelings, which in turn fosters a good attitude to the HPT itself as well as to life (happiness balance).

During the HPT the students experienced an increase in pleasant feelings and a decrease in unpleasant feelings, which are likely to be experienced by their future patients. The therapist’s personal experience of contact with a horse is the best way to understand and consciously apply the therapeutic method of HPT.

Experiencing a surge in pleasant feelings during HPT, is associated with an increase in heart rate and stimulation of the autonomic nervous system and may translate into stimulation of the vagus nerve – especially in women.

There is a need to enrich the didactic offer directed to physiotherapy students with practical HPT classes in Poland.

Limitations

The limitation of the presented research is the lack of control of variables that may have a significant impact on the obtained results. Such variables include: different weather conditions accompanying three days of classes for six consecutive years, different times of the day in which classes take place in subsequent sessions, and the level of initial anxiety accompanying students before the first practical horse riding. We also did not take into account the cultural context when collecting and interpreting data. In continuing research, it is important to consider the control of these variables during the intervention. The cultural context in which the results were obtained was also not taken into account. Diener et al15 propose such analyzes because the results obtained in SPANE, based on a respondent's judgments about their feelings, may differ between cultures. Because of the general items included in the scale, the score may reflect not only pleasant and unpleasant emotional feelings, but also other states such as interest, flow, positive engagement, and physical pleasure. It assesses the full range of positive and negative experiences, including specific feelings that may have unique labels in specific cultures.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Choińska AM, Żurek A, Gieysztor E, Górna S, Trafalska A, Selwa D, The influence of contact with a horse on emotions of physiotherapy students, Hippotherapeutic review 2017/1 (18). Warsaw; 2017.

2. Guindos-Sanchez L, Lucena-Anton D, Moral-Munoz J, Salazar A, Carmona-Barrientos I. The effectiveness of hippotherapy to recover gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children. 2020;7(9):106. doi:10.3390/children7090106

3. Lucena-Antón D, Rosety-Rodríguezb I, Moral-Munozac JA. Effects of a hippotherapy intervention on muscle spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:188–192. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.013

4. Dominguez-Romero JG, Molina-Aroca A, Moral-Munoz JA, Luque-Moreno C, Lucena-Anton D. Effectiveness of mechanical horse-riding simulators on postural balance in neurological rehabilitation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010165

5. Koca TT. What is hippotherapy? The indications and effectiveness of hippotherapy. North Clin Istanbul. 2016;2(3):247. doi:10.14744/nci.2016.71601

6. Smith AV, Proops L, Grounds K, Wathan J, McComb K. Functionally relevant responses to human facial expressions of emotion in the domestic horse (Equus caballus). Biol Lett. 2016;12:20150907. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0907

7. Sabiniewicz A, Białek M, Tarnowska K, Swiątek R, Dobrowolska M, Sorokowski P. A Preliminary Investigation of Interspecific Chemosensory Communication of Emotions: Can Humans (Homo sapiens) Recognise Fear- and Non-Fear Body Odour from Horses (Equus ferus caballus). Animals (Basel). 2021;11(12)3499. doi:10.3390/ani11123499

8. Bizub AL, Joy A, Davidson L. It’s like being in another world” Demonstrating the benefits of therapeutic horseback riding for individuals with psychiatric disability. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2003;26(4):377-384.

9. Choińska AM, Sadowska L, Filipowski H, et al. Występowanie stresu u studentów fizjoterapii realizujących program dydaktyczny z zakresu specjalnych metod hipoterapii [The occurrence of stress in physiotherapy students implementing a didactic program in the field of special methods of hippotherapy]. Przegląd Hipoterapeutyczny. 2011;1(12). [Polish]

10. Eyler J, Giles DE, Jnr. Where's the Learning in Service-Learning? Astin AW, editor. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1999.

11. Buswell D, Leriou F. Perceived Benefits of Students’ Service-Learning Experiences with Hippotherapy. Faculty Publication. 15. Available from http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/kinesiology/15

12. Emes C, Velde BP. racticum in adapted physical activity. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005.

13. Sherrill C. Service-learning, practicums, internships: issues in professional preparation. Palaestra. 2006;22(4):55–56.

14. Eyler JS, Giles DE Jr, Stenson CM, Gray CJ. At a glance: What we know about the effects of service-learning on college student, faculty, institutions and communities, 1993-2000 (3rd ed.). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University; 2000.

15. Diener E, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

16. Daniel-González L, de la Rubia JM, Valle de la OA, García-Cadena CH, Martínez-Martí ML. Validation of the Mexican Spanish version of the scale of positive and negative experience in a sample of medical and psychology students. Psychol Rep. 2020;123(5):2053–2079. doi:10.1177/1359105313478644

17. vera-Villarroel P, Pavez P, Silva J. El rol predisponente del optimismo: hacia un modelo etiologico del bienestar [The causal role of the optimism: towards an etiological model of well-being]. Terapia Psicologica. 2012;30(2):77–84. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082012000200008

18. Pakenham KI, Stafford-Brown J. Stress in clinical psychology trainees: current research status and future directions. Aust Psychol. 2012;47(3):147–155. doi:10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00070.x

19. Ruiz-Aranda D, Extremera N, Pineda-Gala NC. Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and subjective happiness in female student health professionals: the mediating effect of perceived stress. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(2):106–113. doi:10.1111/jpm.12052

20. Cassaretto M, Martinez P. Validacion de las escalas de bienestar, de florecimiento y afectividad [Validation of the scales of well-being of flourishing and feelings]. Pensamiento Psicologico. 2017;15(1):19–31. doi:10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI15-1

21. Carmona-Halty M, Villegas-Robertson M. Escala de experiencias positivas y negativas (SPANE): adaptacion y validacion en un contexto escolar chileno [Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE): adaptation and validation in a Chilean school context]. Revista de Ciencia y Tecnologia de America. 2018;43(5):317–321.

22. Silva AJ, Caetano A. Validation of the flourishing scale and Scale of Positive and Negative Experience in Portugal. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110(2):469–478. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9938-y

23. Howell AJ, Buro K. Measuring and predicting student well-being: further evidence in support of the flourishing scale and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experiences. Soc Indic Res. 2015;121(3):903–915. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0663-1

24. Jovanović V. Beyond the PANAS: incremental validity of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) in relation to well-being. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;86:487–491. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.015

25. Telef BB. The positive and negative experience scale adaptation for Turkish university students. Eur Sci J. 2015;11(14):49–59. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3987.3124

26. Rahm T, Heise E, Schuldt M. Measuring the frequency of emotions - validation of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) in Germany. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):1–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171288

27. Giuntoli L, Ceccarini F, Sica C, Caudek C. Validation of the Italian versions of the flourishing scale and of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience. SAGE Open. 2017;7(1):1–12. doi:10.1177/2158244016682293

28. Li F, Bai X, Wang Y. The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE): psychometric properties and normative data in a large Chinese sample. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):1–9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061137

29. Sumi K. Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the flourishing scale and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience. Soc Indic Res. 2014;118(2):601–615. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0432-6

30. Singh K, Junnarkar M, Jaswal S. Validating the flourishing scale and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience in India. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2016;19(8):943–954. doi:10.1080/13674676.2016.1229289

31. Tilešová- Rychlewska Stanislava: Good Practices in Hippoterapy what every hippotherapist should know psycho-pedagogically and psychotherapeutically,Association 'Strapete Ranch'. Bełchatow; 2016.

32. Earles JL, Veronon LL, Yetz JP. Equine - assisted therapy for anxiety and posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(2):149–152. doi:10.1002/jts.21990

33. Kern Godal A, Brenna JH, Koqstad N, et al. Contribution of the patient - horse relationship to substance use disorder treatment: patients’ experiences. Int J Qual Stud. 2016;11:31636.

34. Strauß I, Transl from German. Elżbieta Karpińska-Pawlak: Hippotherapy: physiotherapy on and with the horse, Wyd. 4. Krakow: Hippotherapy Foundation - for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Children; 2012.

35. Cabiddu R, Silva AB, Trimer R, et al. Hippotherapy effects on the autonomic cardiac control in children with neurological disorders. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(5S):981–982. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000487950.72122.d1

36. Smith D. Hippotherapy and Therapeutic Riding: Practicing Social Workers and Undergraduate Social Work Students. Social Work Theses; 2010:59. Available from: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/socialworkstudents/59

37. Little PMD, Harris E. A Review of Out-of-School Time Program Quasi-Experimental and Experimental Evaluation Results. Out-of-School Time Evaluation Snapshot. Harvard Family Research Project; 2003. Available from: https://archive.globalfrp.org/evaluation/publications-resources/a-review-of-out-of-school-time-program-quasi-experimental-and-experimental-evaluation-results

38. Astin AW, Sax LJ. How undergraduates are affected by service participation. J Coll Stud Dev. 1998;39:251–263.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.