Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 12

The conundrum of indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB Gold results before anti-tumor necrosis factor initiation

Authors Hakimian S , Popov Y, Rupawala AH, Salomon-Escoto K, Hatch S, Pellish R

Received 13 September 2017

Accepted for publication 1 November 2017

Published 27 February 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 61—67

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S150958

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Shahrad Hakimian,1 Yevgeniy Popov,1 Abbas H Rupawala,2 Karen Salomon-Escoto,3 Steven Hatch,4 Randall Pellish1,2

1Department of Medicine, 2Division of Gastroenterology, 3Division of Rheumatology, 4Division of Infectious Disease, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA, USA

Background: Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is a key cytokine in both the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the host defense against tuberculosis (TB). Consequently, anti-TNFα medications result in an increased risk of latent TB infection (LTBI) reactivation. Here, we sought to evaluate the factors affecting the results of QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay as a screening tool for LTBI.

Methods: We conducted an observational, retrospective study in patients with IBD and RA who underwent LTBI screening using QFT-GIT at UMass Memorial Medical Center between 2008 and 2016 prior to initiation of anti-TNF medications.

Results: We included 107 and 89 patients with IBD and RA, respectively. We found that a higher proportion of IBD patients had indeterminate QFT-GIT result compared to RA patients. Furthermore, we found that the majority of patients with indeterminate results were tested during an acute flare of IBD (88%) and while taking corticosteroids. Of all patients receiving ≥20 mg equivalent prednisone dose (n=32), 63% resulted in indeterminate QFT-GIT, compared to only 6% indeterminate testing in patients receiving <20 mg of equivalent prednisone dose (n=164, P<0.001). There was no correlation between indeterminate results and age, gender, disease duration, or distribution, or smoking status within each population.

Conclusion: We observed that high-dose corticosteroids may affect QFT-GIT outcomes leading to a high proportion of indeterminate results. We propose that IBD patients should be tested prior to initiation of corticosteroids to avoid equivocal results and prevent potential delays in initiation of anti-TNF medications.

Keywords: indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB Gold, latent TB infection, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, corticosteroids, IBD flare

Introduction

An estimated 2 billion people worldwide are affected by latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI).1,2 Many patients with LTBI never exhibit any signs of infection and remain asymptomatic for many years. However, LTBI reactivation remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Globally, 8.8 million new cases of active infections are diagnosed annually resulting in 1.8 million deaths.3 The incidence of both active and latent tuberculosis (TB) in the US is lower than global average.4 However, reactivation of LTBI in at-risk patients, particularly immunosuppressed patients, remains a concern.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is a key cytokine in pathogenesis of various inflammatory conditions including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)5 and rheumatoid arthritis (RA); therefore, blockade of the TNFα signaling pathway is very effective in the treatment of these diseases.6 Furthermore, TNFα is also a key cytokine in the development and maintenance of the granuloma that compartmentalizes tuberculous bacilli and therefore plays a major role in protective host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB).7 Consequently, TNFα inhibitors result in an increased risk of LTBI reactivation8 and have been implicated in several deaths.9,10 Therefore, screening for LTBI is the standard protocol prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy.11 However, the best screening strategy in this population remains controversial.

The tuberculin skin test (TST) is the older method of screening for LTBI.12 TST is performed by injecting purified protein derivative (PPD) into the forearm and measuring the diameter of skin induration after 48–72 h.13 PPD is a species nonspecific precipitate of MTB derivatives and relies on the ability of the immune system to form skin induration in response to the foreign antigen.14 Therefore, TST has low sensitivity and specificity, especially in the population of patients with inflammatory condition and patients previously vaccinated with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG).15 Evidence indicates that patients with active IBD or RA may exhibit anergy in up to 80% of cases especially in the presence of corticosteroids resulting in false-negative results,16–18 which lowers the sensitivity even further.

More recently, several companies have developed blood tests known as interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) as an alternative to TST in screening for LTBI.19–21 These assays employ the innate ability of T cells to release interferon gamma in response to exposure to specific antigens. QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay is an IGRA that uses ELISA to quantify interferon-gamma release in vitro when patient’s whole blood is exposed to a cocktail of 3 mycobacterial proteins (ESAT-6, CFP-10, and TB 7.7). This protein cocktail is more specific to MTB and does not cross-react with prior BCG vaccination,22 increasing the specificity of the test. Additionally, QFT-GIT includes internal positive and negative controls to increase the sensitivity of the test. However, there are only a few reports23–25 that evaluate the utility of LTBI screening by QFT-GIT in a setting of active inflammation or steroid use. Here, we sought to evaluate the factors that affect the results of QFT-GIT when used specifically as a screening tool for LTBI prior to initiation of anti-TNF medications.

Methods

This observational, retrospective, single-center study included patients with IBD (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) and RA who underwent screening for LTBI using QFT-GIT at UMass Memorial Medical Center between 2008 and 2016 prior to initiation of anti-TNF medications. Patients were identified through billing codes, and the diagnoses were verified by chart review of clinical data. Inclusion criteria included age >18 years, correct diagnosis of IBD and RA, and available QFT-GIT results. Our protocol was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB), application number H00010536. A waiver of consent was granted by the IRB as the data were retrospective and included older records that could not be reasonably tracked back to all individual patients, some of whom have moved or passed away since. Such inclusion of missing data would add selection bias and limit data interpretation. Data extracted for analysis included demographics, disease phenotype, duration of disease, measures of disease activity, imaging, and endoscopic data. All data collection was conducted in accordance with state, local, and federal laws and as approved by the IRB.

IBD was defined by the presence of symptoms consistent with IBD in addition to objective inflammation as evidenced by elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], and fecal calprotectin), computed tomography (CT) findings of inflammation consistent with IBD, and/or endoscopic findings consistent with IBD. RA diagnosis was based on American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative 2010 classification criteria.26 IBD and RA flare were defined by treating clinician’s determination. This determination was generally based on worsening of symptoms, elevation of inflammatory markers, new or worsening imaging or endoscopic evidence of inflammation. RA disease severity was assessed based on 2 commonly used previously validated scoring systems for RA: global assessment of RA and disease activity assessment (DAS 28). Corticosteroid dosing is presented in oral prednisone dose equivalents.

Patient’s blood samples were tested for LTBI using QFT-GIT manufactured by QIAGEN NV (Venlo, the Netherlands), run by Quest Diagnostics Laboratory. In this technique, each patients’ blood sample was collected in 3 separate tubes. Qnil tube contained all test components but no TB antigen. This tube, therefore, serves as the negative control for the test and controls for background interferon-gamma release as measured by ELISA. Qmito tube contains mitogen, a mixture of components that should always result in interferon-gamma release regardless of prior to exposure to TB. This tube serves as the positive control for the test and assesses the ability of the immune cells in the blood sample to mount a response and produce interferon gamma in response to antigens. The third tube, TB-Ag, contains a cocktail of 3 mycobacterial proteins (ESAT-6, CFP-10, and TB 7.7) and should only result in interferon-gamma release in the case of prior exposure to MTB. Positive QFT-GIT result is defined per manufacturer as a TB-specific antigen response of >0.35 (IU/mL) with any mitogen control response. Negative result is defined as a TB antigen response of <0.35 (IU/mL) and a mitogen control response of >0.5 (IU/mL). Indeterminate response is defined as a TB antigen response of <0.35 (IU/mL) and a mitogen response of <0.5 (IU/mL). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for binary variables.

Results

We identified 196 patients who underwent screening for LTBI using QFT-GIT prior to initiation of anti-TNF therapy. This included 107 patients with IBD (90 Crohn’s disease and 17 ulcerative colitis) and 89 patients with RA. There were 61 (57%) male and 46 (43%) female patients in the IBD group and 20 (22%) male and 69 (78%) female patients in the RA group. Baseline characteristics, disease duration, and distribution are presented in Table 1.

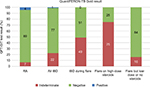

In the IBD group, 82 patients (77%) had a negative QFT-GIT result, 24 patients (22%) had an indeterminate result, and 1 (1%) patient had a positive result. Of the IBD patients with indeterminate results, 21 of 24 patients (88%) were tested during an acute flare. We, therefore, further analyzed the QFT-GIT results of all IBD patients tested during a flare and found that 21 of 43 (49%) patients had an indeterminate test result. Further stratification by steroid treatment within this group (IBD patients during a flare) showed that 18 of 24 (75%) patients on high-dose (≥20 mg) steroids had indeterminate test results as opposed to 3 of 19 (16%) who were on low dose (<20 mg) or no steroids. By contrast, in the RA cohort, 79 patients (89%) had a negative QFT-GIT result, 6 patients (7%) had indeterminate result, and 4 patients (5%) had positive results (Figure 1). There was no correlation between having an RA flare and indeterminate result in this group.

We next sought to evaluate the factors influencing the outcome of the QFT-GIT test. In our cohort, we found no correlation between an indeterminate QFT-GIT and age, gender, disease duration, or distribution, or smoking status within each population (IBD data shown in Table 2). However, there was a strong correlation between an indeterminate QFT-GIT and active Crohn’s flare (peak ESR and CRP). Additionally, there was also a strong correlation between indeterminate QFT-GIT and corticosteroid use with a significantly higher rate of indeterminate results at an equivalent prednisone dose of ≥20 mg (Table 2B). As expected, indeterminate result was observed with inadequate response to positive control in the test (mitogen) (Figure S1).

Discussion

LTBI screening remains the standard protocol before initiating anti-TNF therapy. However, there are currently no standard methods of LTBI screening in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions such as IBD and RA. An ideal screening strategy should include a detailed history of risk factors for LTBI, as well as laboratory testing based on those risk factors. However, the most accurate laboratory test, and the ideal timing of testing, remains to be determined.

We examined the role of QFT-GIT assay as a screening tool for LTBI before initiation of anti-TNF therapy in a setting of active inflammation and corticosteroid use. We found that a high proportion of IBD patients have indeterminate results during active flares. No similar correlation was found in the RA population, though our RA cohort were generally treated less frequently with steroids and generally at lower doses at the time of testing. Furthermore, we found that corticosteroid treatment at the time of testing may be responsible for a high proportion of these indeterminate results as observed in our IBD patients, with higher indeterminate rates associated with higher steroid doses. This result, we suspect, is due to a blunted interferon-gamma response to the positive control (mitogen) portion of the IGRA test.

The question of whether RA patients can be reliably tested for LTBI with QFT-GIT while on corticosteroids remains open. Further studies exploring the association with higher doses of steroids may answer this question more specifically. However, the results in the IBD cohort suggest that, when possible, a patient with RA should ideally be tested for LTBI off steroid therapy and prior to initiation of TNFα inhibitors to minimize the chance of indeterminate result.

Despite our findings regarding high rates of indeterminate IGRA results, IGRAs such as QFT-GIT continue to serve as a useful tool for LTBI screening in the IBD population. IGRAs have previously been shown to have better sensitivity and specificity than TSTs in the general population.19 Other studies suggest that IGRAs may also be more sensitive than TSTs particularly in the IBD population during acute flares. The inclusion of a positive control distinguishes IGRAs from more traditional testing with TSTs. The TST has only a single readout, the appearance of a wheal, and does not have a positive control equivalent to the IGRA “mitogen” tube to determine whether the immune system is capable of mounting a response. Thus, the TST provides no method to readily distinguish between true- and false-negative results. This can markedly decrease the sensitivity of the test in the setting of an acute flare or corticosteroid treatment. Indeed, studies have reported high rates of anergy with TST in the setting of IBD and RA flares.16,17

By contrast, IGRAs such as QFT-GIT assay do have additional positive and negative controls (mitogen and nil antigen, respectively) to serve as internal quality controls for the test, thereby decreasing the false-positive and false-negative rates and increasing the sensitivity and specificity of the test, especially in a setting of corticosteroids when the sensitivity of the test might otherwise be compromised. Indeed, indeterminate QFT-GIT results were found to be more common among patients with negative TST results in an inpatient hospital population, many of whom were on immunosuppressive medications.27 IGRAs such as QFT-GIT are often chosen over TSTs when possible in the IBD population on corticosteroids when the corticosteroids cannot be practically weaned off before LTBI screening prior to initiation of anti-TNF therapy.

Our findings raise the question of how one might deal with indeterminate results. In these situations, one has to resort to clinical judgment based on patients’ TB risk factors and likelihood of disease. In our experience, some even suggest empirically treating high-risk patients for LTBI until more definite testing can be obtained off corticosteroids by repeat testing. However, one must balance the risk of LTBI reactivation in such patients with the risk of complications from treatment in a potentially uninfected individual. LTBI treatment is not a zero-risk proposition, and the risks of rash, liver toxicity, and drug–drug interactions remain a concern. The indeterminate results pose significant management questions.

Our study has certain limitations. First, it is a retrospective study that could not control for age differences in IBD and RA populations or doses of corticosteroids in each group. In this study, we have observed a lower rate of indeterminate results in the RA compared to IBD population. However, caution should be advised as patients in the RA group tend to have lower rates of corticosteroids treatment and are on lower doses of prednisone equivalents. Therefore, the difference seen here may not necessarily be specific to the disease process but rather the effect of corticosteroids. However, larger randomized controlled trials controlling for age, gender, and steroid dose may elucidate other differences. Selection bias is also possible due to the retrospective nature of the study and ICD code-based ascertainment of diagnosis which may unintentionally exclude certain patients with RA and IBD. Future studies may evaluate whether the inflammatory process in IBD itself can interfere with QFT-GIT results in the absence of corticosteroids.

The consideration of instituting anti-TNF treatment, particularly in patients with IBD in the throes of an acute flare, often requires urgent decision-making. Such clinical scenarios can include the emergent consideration of anti-TNF therapy to treat steroid-refractory disease and possibly avoid the need for surgical intervention. An indeterminate QFT-GIT result can delay induction with an anti-TNF medication while attempting to determine an appropriate response to the indeterminate result and the best treatment approach to possible LTBI. With our results indicating an association between steroid use and indeterminate QFT-GIT results, we suggest testing with QFT-GIT prior to initiation of, or even before the consideration of, steroids to prevent delays in initiation of anti-TNF therapy if needed later in a patient’s course. Accordingly, many experts advocate TB testing at an initial encounter (or at initial diagnosis) of IBD to avoid any urgent scenario of delay in anti-TNF induction due to an indeterminate LTBI test.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Jonathan Kay for help with access to RA database used to gather part of the data. Part of the data was presented as a poster at American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV, USA, in October 2016.

Author contribution

SH, AHR, and RP designed the study. SH and YP collected the data. All the authors helped with interpretation of the data, drafting the article or revising it critically, and provided final approval of the submitted version.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Ncayiyana JR, Bassett J, West N, et al. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection and predictive factors in an urban informal settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):661. | ||

Houben RM, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. | ||

Zumla A, George A, Sharma V, et al. The WHO 2014 global tuberculosis report – further to go. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e10–e12. | ||

Mancuso JD, Diffenderfer JM, Ghassemieh BJ, Horne DJ, Kao TC. The prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(4):501–509. | ||

Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:289–298. | ||

Lin J, Ziring D, Desai S, et al. TNFalpha blockade in human diseases: an overview of efficacy and safety. Clin Immunol. 2008;126(1):13–30. | ||

Flynn JL, Chan J, Lin PL. Macrophages and control of granulomatous inflammation in tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4(3):271–278. | ||

Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(15):1098–1104. | ||

Malipeddi AS, Rajendran R, Kallarackal G. Disseminated tuberculosis after anti-TNFalpha treatment. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):162. | ||

Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1409–1422. | ||

Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(6):443–468. | ||

Koch R. An address on bacteriological research. Br Med J. 1890; 2(1546):380–383. | ||

Chaparas SD, Vandiviere HM, Melvin I, Koch G, Becker C. Tuberculin test. Variability with the Mantoux procedure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132(1):175–177. | ||

Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):15–21. | ||

Tissot F, Zanetti G, Francioli P, Zellweger JP, Zysset F. Influence of bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination on size of tuberculin skin test reaction: to what size? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(2):211–217. | ||

Mow WS, Abreu-Martin MT, Papadakis KA, Pitchon HE, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA. High incidence of anergy in inflammatory bowel disease patients limits the usefulness of PPD screening before infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(4):309–313. | ||

Agarwal S, Das SK, Agarwal GG, Srivastava R. Steroids decrease prevalence of positive tuberculin skin test in rheumatoid arthritis: implications on anti-TNF therapies. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2014;2014:430134. | ||

Taxonera C, Ponferrada Á, Bermejo F, et al. Early tuberculin skin test for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(7):792–800. | ||

Schoepfer AM, Flogerzi B, Fallegger S, et al. Comparison of interferon-gamma release assay versus tuberculin skin test for tuberculosis screening in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(11):2799–2806. | ||

Karataş Toğral A, Muştu Koryürek Ö, Şahin M, Bulut C, Yağci S, Ekşioğlu HM. Association of clinical properties and compatibility of the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test with the tuberculin skin test in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(6):629–633. | ||

Bae W, Park KU, Song EY, et al. Comparison of the sensitivity of QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube and T-SPOT.TB according to patient age. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156917. | ||

Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM, Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1099–1104. | ||

Papay P, Eser A, Winkler S, et al. Predictors of indeterminate IFN-gamma release assay in screening for latent TB in inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41(10):1071–1076. | ||

Helwig U, Muller M, Hedderich J, Schreiber S. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy influence the result of QuantiFERON TB Gold testing in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(4):419–424. | ||

Bélard E, Semb S, Ruhwald M, et al. Prednisolone treatment affects the performance of the QuantiFERON gold in-tube test and the tuberculin skin test in patients with autoimmune disorders screened for latent tuberculosis infection. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2340–2349. | ||

Kay J, Upchurch KS. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(Suppl 6):vi5–vi9. | ||

Ferrara G, Losi M, Meacci M, et al. Routine hospital use of a new commercial whole blood interferon-gamma assay for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(5):631–635. |

Supplementary material

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.