Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 13

The Awareness of Violence Reporting System Among Healthcare Providers and the Impact of New Ministry of Health Violence Penalties in Saudi Arabia

Authors Towhari AA , Bugis BA

Received 14 April 2020

Accepted for publication 8 September 2020

Published 9 October 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 2057—2065

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S258106

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Marco Carotenuto

Aisha A Towhari,1,2 Bussma A Bugis3

1Respiratory Care Department, Prince Sultan Military College of Health Sciences, Al-Dhahran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Saudi Electronic University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 3Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Saudi Electronic University, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Aisha A Towhari Respiratory Care Department, Prince Sultan Military College of Health Sciences, Dhahran P.O. Box 946, 31932, Saudi Arabia

Tel +966 13 8440000

, EXT: 3603 Email [email protected]

Purpose: Healthcare professionals are one of the most vulnerable groups subjected to verbal and physical violence daily while carrying out their duties; such violence is a worldwide concern. This study aimed to explore the awareness of a violence reporting system among healthcare providers and the impact of the new Ministry of Health (MOH) violence regulations at one of the Eastern Region hospitals in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted from January to February 2020. The study included 210 healthcare providers from different specialties working in critical care units. A sample of 137 healthcare providers was selected randomly, and a self-administered questionnaire was distributed accordingly.

Results: In this study, 31.4% of participants were not aware of whether they had a specific system for reporting violent incidents, while 68.6% had no training on these systems. Experiences of violence among the staff decreased from 78.6% before the MOH regulations to almost 20% after the MOH regulations.

Conclusion: The majority of victims did not report incidents because there is a lack of system privacy, and the workers felt that the incidents of violence were a part of their daily jobs. In addition, this study revealed that the majority of healthcare workers did not receive training on the reporting system, which explains their lack of knowledge about the formal reporting system. Finally, the MOH initiative and penalties for controlling workplace violence have resulted in a significant drop in the prevalence of violence among healthcare workers.

Keywords: Saudi Arabia, violence penalties, Ministry of Health, reporting of violence, healthcare workers

Introduction

Violence in the workplace is the deliberate use of force, either threatened or actual, against another person or a group in work-related circumstances, that results in either injury, death, psychological harm, poor performance, or deprivation.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) describes violence in the workplace as incidents in which workers are harassed, threatened, or assaulted in job-related settings, including commuting to and from work, involving a direct or indirect challenge to their safety, well-being or health2. Violence in health institutions can be physical, verbal, or psychological.3

Healthcare workers are at a greater risk of verbal and physical abuse compared to the workers in any other occupational sector.4 These widespread unethical attacks lead to significant corruption of the fluency of patient care in particular and of the healthcare system in general.5 Studies showed that the workplace violence in the healthcare sector might result in poor-quality services, turnover, absenteeism among healthcare professionals, the deterioration of public health services, unsafe work environments, inappropriate social behavior, increased health costs, and the degradation of healthcare workers.6,7

Today, violence in the workplace is generally accepted as a common occurrence in medical jobs; studies showed that 24–88.8% of healthcare workers have experienced violent incidents each year.8 A study conducted in China found that the main reason for such violence was poor quality of care; one million cases of violence against healthcare providers were reported annually.9 In Egypt, 78.2% of physicians were exposed to violence annually.10 The most common unit in the hospital subjected to violence was the Emergency Department,11 where the source of violence is the patient’s families/friends in Middle East.12 According to AlBashtawy, the reasons for violence were long waiting time, unmet patients/families expectation and over-crowding.13 These violent incidents resulted in a significant decrease in healthcare providers’ self-esteem as statistics have shown that 70% of physicians prefer for their children to not enter the medical field because of violent behaviour.14,15

Workplace violence against healthcare professionals in the Middle East has been thoroughly studied recently.16–18 Although government policies and regulations are in place, the rate of workplace violence in the Middle East, such as in Saudi Arabia, is quite high.16 In Saudi Arabia, over two-thirds of healthcare professionals have experienced some form of violence, from either patients or their families.19 According to Algwaiz’s study, verbal violence is the most common source of violence; the main causes of such abuse are long wait times, staff shortages, and under-expectation of patient demands.19

Moreover, the media has played a negative role by reflecting a poor image of focusing on the malpractice of healthcare.14 Breaking news on the media and television channels about the deaths of patients owing to negligence by the physician has only served to work against patients’ own benefit, as well as against healthcare practitioners.20 This has resulted in mistrust between patients and healthcare providers and triggered widespread violent incidents; in fact, many practitioners are aiming to undergo self-defense training to protect themselves.14

Most acts of violence remain unknown and under-reported.21 Therefore, we do not know the actual level of workplace violence that occurs. This includes studying the behaviors of medical staff following abuse in the workplace and finding reasons why most victims do not appropriately disclose violent acts.21 Unfortunately, healthcare facilities have weak violence prevention system and major concern with training program, as the focus has always been more on patient satisfaction than workers’ protection.22 In fact, all these violent incidents against healthcare providers who lacked support from their hospital administration had highly impacted the staff’s psychological status.23 As reported by Tonso et al, 33% of victims of violence developed distress.23 An even higher rate (64.2%) was reported by Basfr et al in their study, which was conducted in psychiatric hospitals.24

Therefore, reporting violent events is an essential element to plan for future effective preventive methods.25 The lack of staff training in handling aggressive behavior and the absence of a system/process for violence prevention could be related to underreported events.26 A study conducted in Saudi Arabia found that the reasons for the lack of violence reporting among nurses were the inadequate reporting procedures, mistrust of the reporting system, and a lack of belief in the effectiveness of the violence prevention system.17 These alarming findings from both national and international studies emphasize the urgent need for preventive measures and strict policies to prevent violent behaviour.21,25,27 By applying such measures, healthcare providers will feel safe in the workplace in order to effectively perform their duties and provide high-quality healthcare.21,25 The culture of acceptance of patients’/relatives’ aggressive behavior is widespread among healthcare workers, though it should not be accepted unless the violence was unintentional.25,28

Violence against healthcare providers has been neglected and underestimated for a long time. However, currently, this occupational hazard is receiving wide attention. In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Health (MOH) implemented fines and penalties in July 2018 to control and prevent the occupational hazard of violence. The MOH stated, ″The verbal and physical abuse against the health practitioners is a crime punished by law, with imprisonment up to 10 years”29 In addition, a line of service center (937) was introduced for immediately reporting and communicating about any verbal or physical abuse against healthcare practitioners.29 This humble yet extensive research revealed that there is a lack of studies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that assess the availability and the knowledge of healthcare providers in regards to the violence reporting system/procedure in the hospitals of Saudi Arabia. This study aimed to explore the awareness of a violence reporting system among healthcare providers, and the impact of the MOH violence regulations in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study is a descriptive, cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study targeting healthcare providers in critical care units in the hospital. The information was collected at one point in time to explore the knowledge of the violence reporting system and the impact of MOH violence penalties.

Study Population and Sampling Technique

The targeted hospital was a tertiary hospital with a current population of 210 healthcare providers working in the Intensive Care Units (ICU). Healthcare providers in the ICU include nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, nutrition specialists, pharmacists, and social workers. With a 95% confidence level, a margin of error of 5%, and using the Raosoft sample size calculator available online, the calculated sample size is 137 healthcare providers. Inclusion criteria are all healthcare providers with at least two years of experience and working in any critical care unit. Exclusion criteria are any healthcare provider with less than two years of experience and not working in a critical care unit. The time of at least two years was set in this study as an inclusion criterion because the MOH violence penalties were launched in July 2018.

The data were collected from three Intensive Care Units from January to February 2020 through the use of a self-administered questionnaire in the English language after the approval of the research by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Prince Sultan Military College for Health Science (PSMCHS) in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The self-developed questionnaire was pilot-tested by 10 expert healthcare providers to effectively capture the topic under investigation and to control the errors in questions and understanding. The anonymous questionnaire contained three sections: Section #1: Demographic data. Section #2: Questions regarding the knowledge of violence reporting system and how they respond to violence. Section #3: Questions about the impact of the new MOH violence penalties law and how violence would be mitigated. The questions were in the form of Yes/No and multiple-choice questions. The last question was an open-ended question seeking participants’ opinions about enhancing the reporting system and ideas to mitigate violent incidents. A randomized sampling was conducted by Excel program to ensure the correct representation of our population and study variables.

The information sheet that contains the aim of the study, contact information for inquiries, and the right to withdraw questionnaires completion was given to each participant, thus informed signed consent was obtained then from participants who agreed to participate in this study before distributing the questionnaires. Participants’ confidentiality and data privacy were ensured by maintaining completely anonymous involvement in the study and were clearly written in the questionnaire’s face sheet.

Statistical Analysis and Study Variables

After collection of the sheets, each sheet was coded into serial numbers using the Excel program. The variables were transferred as categorical data to the variable sheet of SPSS. Descriptive analysis was done for demographic data such as education degree, years of experience, gender, and specialty, which were reported as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square analysis was used to find the association between dependent and independent variables. Dependent variable was violence reporting system awareness and independent variables were violence reporting system training and years of experience. All statistical tests were considered significant with a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Demographic Analysis

Responses were achieved with 135 completed questionnaires out of 137 distributed surveys (98% response rate). Fourteen responses were excluded because they came from workers who had less than two years of experience or who did not work in critical care units. Most respondents were females (66.9%), while those with a bachelor’s degree constituted 86.6% of the study sample. The majority of respondents were 26 to 30 years old (42.1%), while most respondents had from 6 to 10 years of experience (38%). The dominant occupation in the study sample was nurses at 72.7%, followed by respiratory therapists at 21.5% (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic Data |

Sources of Violence and Incidents Report

Regarding exposure to violence, 56 out of 121 (46%) respondents had been exposed to verbal assaults only, while 37 respondents (30.6%) had been victims of both verbal and physical violence (Figure 1). Only 26 respondents (21.5%) had experienced no violence in their work setting. The most common source of violence in the study was the patient’s relatives/friends or visitors, which accounted for 44.5%. When victims were asked to select all applicable reasons for violence, the majority reported that a lack of security personnel and the patient’s health condition were the two most frequent causes. Thirty-six victims believed that the causes of assaults are the shortage of staff and the poor image of healthcare providers. Over 85% of participants believed that social media news about patients’ deaths and injuries triggers violence attacks by the patients and their relatives.

|

Figure 1 Types of violence experienced by healthcare workers. |

Regarding the reporting of these incidents, 44.6% did not report violent events and only 34.7% of the victims had reported the violence to different channels. The common reporting channels, as indicated by the respondents, were direct supervisors and electronic reporting systems, with 11.6% and 10.7%, respectively. The most frequent reasons for not reporting these episodes were the lack of system privacy (26.35%), feeling that violence is a part of the job nature (25.15%), and the fear of consequences (20.96%) (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Reasons of unreported violence incidents. |

Awareness and Availability of a Reporting System

When participants were asked if they had a formal or electronic reporting system in their healthcare organization, 53.7% reported that they were aware of the availability of incident reporting system, while 15.9% had no reporting system. Unfortunately, 31.4% were not aware of whether they had a specific system for incident reports and 68.6% had no training on these systems.

Negative Consequences

The most frequently reported negative consequence that was reported by 78 respondents (37%) was a negative effect on their overall health and well-being (depression, anxiety, fear, and anger). This was followed by two negative outcomes with the same percentage (24% for each), ie, violence led them to consider changing/leaving their job and decreased their motivation to work.

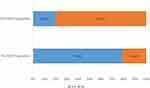

MOH Violence Penalties

When respondents were asked if their violence reporting behavior had changed and whether they were encouraged to report violent events after the launch of the MOH penalties, the majority (43%) were not sure. Only 26.4% replied with yes, while 17.4% said that it had no impact on their reporting behavior. Ninety-seven participants (80.2%) reported that they had not experienced any form of violence after the MOH implemented the new regulations, comparing with only 26 participants (21.4%) reported that they had not experienced any form of violence before the implementation. On the other hand, 78.6% indicated that they had been exposed to different forms of violence before the implementation, while 19.8% indicated that they had been exposed to violence after the implementation (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Exposure to violence pre and post MOH regulations. |

Overall, 79.3% of respondents felt secure in their workplace after the implementation of the MOH regulations. Over 47% of participants were satisfied, 40.5% had an average satisfaction level, and 11.5% were dissatisfied after the announcement of the MOH regulations. Finally, in terms of healthcare providers’ satisfaction with their hospital violence management system, 33% said that they were satisfied, 43% indicated an average satisfaction, and 23.1% indicated that they were dissatisfied. Study respondents’ most frequent suggestions for lessening violence were to create a special and clear violence reporting system inside the healthcare organization and to expand security staff coverage in hospital units.

Association Among Study Variables

Association was tested by applying Chi-square test analysis between the awareness about the availability of the reporting system and years of experience. There was a significant association between system awareness and years of experience with P-value of 0.008 (Table 2). Workers with more years of experience showed to be more aware of violence reporting system than those with less years of experience. Another association was conducted among awareness about the availability of the reporting system and system training. There was a P-value of 0.000 as workers tend to be more aware of the system if they were received training (Table 3).

|

Table 2 Association Between Violence System Awareness and Years of Experience |

|

Table 3 Association Between Violence System Awareness and Training |

Discussion

In this study, over three-quarters of healthcare workers had been exposed to different forms of violence in the workplace. This finding is more than what was reported in other studies conducted in Saudi Arabia.17,19 However, these variations in the prevalence of violence (as two-thirds of respondents were exposed to violence in Algwaiz’s study, while 30.7% were exposed to violence in Al-Shamlan’s study) could be related to sample size and the time period of exposure, which is in the previous studies was only one year.17,19 Exposure to violence in this study was not limited to one year, but to any event of violence that the participants could have within the past period of their employment, which may explain these variations. On the other hand, the prevalence of violence in this study is similar to that of a previous study done in Egypt, in which almost 78% of respondents indicated that they had been exposed to verbal and physical assaults within the course of one year.10 The fact that over three-quarters of respondents have experienced to violent aggression is alarming the preventive systems in healthcare organizations of Saudi Arabia.

The most common sort of violence in this study was verbal abuse reported by almost half of the respondents. The majority of studies indicated a similar finding, with verbal violence being the most recurrent form of violence.19,30 In one study carried out among emergency nurses in Jordan, there were five violent verbal incidents for every one physical attack.31 The most common source of attack in this study was the patient’s relatives/friends or visitors. This could be related to emotional and stress factors among the patient’s relatives. This finding is consistent with those of other studies, which concluded that the common perpetrators were patients and their relatives.31,33 The patient’s health condition, a shortage of staff, staff workload, and the lack of security personnel were the major violence triggers in this study. This result came in consistent with the recent evidences from middle east.21,32 In fact, efforts must be made to ensure that healthcare workers have a comfortable and safe workplace to guarantee their safety, health, well-being, and overall satisfaction.

The majority of incidents were not reported in this study despite the respondents’ knowledge of the availability of a formal incident report system in their hospital. The primary reasons for under-reported cases were a lack of system privacy and the belief that workplace violence was part of one’s job duties, similar to Al-Shamlan’s findings.17 Therefore, serious investigations should be made to ensure that healthcare workers trust the reporting system and prevention efforts. On the other hand, as indicated above, accepting violence as part of the nature of the job was the second common barrier to reporting cases and highly influenced respondents’ decisions regarding whether to report. These findings of not-reported violent incidents are consistent with the results identified in the literatures.19,28 Moreover, in agreement with the previous study, a lack of report action and following up on cases is one of the preventable causes of reporting.34

The healthcare practitioners in this study indicated that violence has an alarming negative impact on them. The majority of respondents were concerned about their motivation to work and/or were planning to leave/change their job. In addition, their health and well-being were negatively impacted. These negative consequences are similar to those reported in previous studies.21,23,35 Moreover, the majority of respondents believed that social media, by reporting about the poor quality of care and conveying a poor image of healthcare providers, plays a negative role by triggering violent attacks by patients and their relatives; this is consistent with Ahasan’s findings.14,20 Healthcare providers should work in a healthy environment to maintain their health and safety and allow them to provide quality care. Thus, serious initiatives should be implemented by responsible agencies to prevent such abuse and to control the workplace environment.

MOH Regulations for Violent Attackers

In Saudi Arabia, on July 2018, the Ministry of Health (MOH) launched fines and penalties to control and prevent the occupational hazard of violence. The penalties include imprisonment (up to 10 years) for multiple periods, discretionary punishment in front of the healthcare facility where the violence occurred, and a fine of up to one million riyals.29 Also, a line of service center (937) was introduced to enable immediate communication about verbal or physical abuse of healthcare practitioners.

The majority of respondents were not sure if these regulations affected their reporting behavior, as only about 9% of participants had called the service centre. However, they indicated that there had been a significant drop in violent incidents in their workplace. Experiences of violence among the staff has decreased from 78.5% to almost 20%. Moreover, the feeling of security among medical staff, which was the major negative consequence of exposure to violence, showed significant improvement after the new MOH penalties, as about 41% of participants in this study felt secure, while 38% were still not sure about their workplace security. In terms of overall staff satisfaction among participants, 43% were satisfied and 40.5% had an average satisfaction level. These facts had explored the importance of high-level administration interventions in controlling such events and satisfying healthcare providers during their work. In addition, the majority of respondents in this study believed that the creation of a special and clear violence reporting system inside the healthcare organization, the expansion of security staff coverage in hospital units, and public awareness about violence in healthcare settings were the best solutions to lessen aggressive behaviors against them.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that violent attacks—mainly verbal, inflicted by the patient’s relatives/friends—in the healthcare setting are a significant issue. The majority of victims do not report the incidents, as there is a lack of system privacy, and they feel that it is part of their job. The current study revealed that the majority of healthcare workers did not receive training on the reporting system, which explains their lack of knowledge about the formal reporting system. The MOH’s initiative and penalties for controlling workplace violence have resulted in a significant drop in the prevalence of violence and have satisfied healthcare workers. In addition, the trust in the violence reporting system may bring down the number of violence and further investigations are recommended in this regard. Finally, the respondents in this study suggested that public awareness of violence-related issues and the building of an effective reporting system could mitigate this occupational hazard.

The current study has some limitations. First, the study was limited to workplace violence in critical care units of one hospital due solely to time constraints. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to all hospital units. Second, the study was conducted in a public hospital; accordingly, further studies are required to explore this issue in private hospitals. Third, recall bias as the survey’s questions were aimed to explore events in the past.

Further research must be undertaken to address the current study limitations. The key recommendations revealed by this study are: 1) Build an effective reporting and management system inside a healthcare organization and emphasize the importance of serious actions and following up on cases. 2) Conduct multiple public awareness events to address the negative consequences of workplace violence for workers and patients, and to promote overall quality of care. 3) Empower healthcare providers with knowledge about their formal reporting system by conducting training sessions, thereby changing their attitude towards reporting and dealing with such assaults. 4) Engage in periodic investigation by the Ministry of Health (MOH) to ensure safe and healthy environments for both healthcare practitioners and patients.

Acknowledgment

The researchers acknowledge the help of Mr. Zechariah Jebakumar Arulanantham and Mr. Meshal AlEnezi in the data analysis and the help of Mr. Hesham AlDraiweesh in data collection. Special thanks to the Institution Review Board at Prince Sultan Military College for Health Science for issuing the ethical approval to conduct this study. The cooperation of healthcare providers who participated in this study is highly appreciated. The content is under the responsibility of the researchers and does not represent the views of research site.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Cooper CL, Naomi S. Workplace violence in the health sector state of the art. WHO Int; 2020, Available from: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/injury/en/WVstateart.pdf.

2. WHO. World report on violence and health. Who Int; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/.

3. Zainal N, Rasdi I, Saliluddin SM. The risk factors of workplace violence among healthcare workers in public hospital. Malaysian J Med Health Sci. 2018;14(SP2):120–127.

4. Lanctôt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(5):492–501. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.010.

5. Lipscomb JA, El Ghaziri M. Workplace violence prevention: improving front-line health-care worker and patient safety. New Solut. 2013;23(2):297–313. doi:10.2190/ns.23.2.f.

6. Chen S, Lin S, Ruan Q, et al. Workplace violence and its effect on burnout and turnover attempt among Chinese medical staff. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2015;vol 71(6):330–337. doi:10.1080/19338244.2015.1128874.

7. Higazee MZ, Rayan A. Consequences and control measures of workplace violence among nurses. J Nurs Health Stud. 2017;02(03). doi:10.21767/2574-2825.100028.

8. d’Ettorre G, Mazzotta M, Pellicani V, Vullo A. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in emergency departments. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(4–S):28–36. doi:10.23750/abm.v89i4-S.7113.

9. Liebman BL. Malpractice Mobs: medical dispute resolution in China. Columbia Law Rev. 2013;113(1):181.

10. Abdel-Salam D. Violence against physicians working in emergency departments in Assiut, Egypt. J High Inst Public Health. 2014;44(2):98–107. doi:10.21608/jhiph.2014.20334.

11. Abdellah RF, Salama KM. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence against health care workers in emergency department in Ismailia, Egypt. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:21. doi:10.11604/pamj.2017.26.21.10837

12. Pector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX, et al. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;vol 51(1):72–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.01.010.

13. ALBashtawy M, Aljezawi M. Emergency nurses’ perspective of workplace violence in Jordanian hospitals: a national survey. Int Emerg Nurs. 2016;24:61–65. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2015.06.005.

14. Ahasan HAMN, Das A. Violence against doctors. J Med. 2014;15(2):106–108. doi:10.3329/jom.v15i2.20680.

15. Hesketh T, Wu D, Mao L, et al. Violence against doctors in China. BMJ. 2012;345:e5730–e5730. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5730.

16. Alshehri FA. Workplace Violence Against Nurses Working in Emergency Departments in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. The University of Adelaide; 2017.

17. Al-Shamlan NA, Jayaseeli N, Al-Shawi M, et al. Are nurses verbally abused? A cross-sectional study of nurses at a university hospital, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2017;24(3):173. doi:10.4103/jfcm.jfcm_45_17.

18. Alkorashy HAE, Al Moalad FB. Workplace violence against nursing staff in a Saudi University hospital. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(2):226–232. doi:10.1111/inr.12242.

19. Algwaiz WM, Alghanim SA. Violence exposure among health care professionals in Saudi Public Hospitals. A preliminary investigation. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(1):76–82.

20. Sun J, Liu S, Liu Q, et al. Impact of adverse media reporting on public perceptions of the doctor-patient relationship in China: an analysis with propensity score matching method. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e022455. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022455

21. Alsaleem SA, Alsabaani A, Alamri RS, et al. Violence towards healthcare workers: a study conducted in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2018;25(3):188–193. doi:10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_170_17

22. Nevels MM, Tinker W, Zey JN, Smith T. Who is protecting healthcare professionals? Workplace violence & the occupational risk of providing care. Am Soc Safe Eng. 2020;65(7):39–43.

23. Tonso MA, Prematunga RK, Norris SJ, et al. Workplace violence in mental health: a victorian mental health workforce survey. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25(5):444–451. doi:10.1111/inm.12232.

24. Basfr W, Hamdan A, Al-Habib S, et al. Workplace violence against nurses in psychiatric hospital settings: perspectives from Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2019;19(1):19. doi:10.18295/squmj.2019.19.01.005.

25. Al Ubaidi B. Workplace violence in healthcare: an emerging occupational hazard. Bahrain Med Bull. 2018;40(1):43–45. doi:10.12816/0047466.

26. Alyaemni A, Alhudaithi H. Workplace violence against nurses in the emergency departments of three hospitals In Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. Nurs Plus Open. 2016;2:35–41. doi:10.1016/j.npls.2016.09.001.

27. Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–937. doi:10.1136/oemed-2019-105849.

28. Hogarth KM, Beattie J, Morphet J, et al. Nurses’ attitudes towards the reporting of violence in the emergency department. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2016;19(2):75–81. doi:10.1016/j.aenj.2015.03.006.

29. MOH. MOH news - sentencing offenders against health practitioners. Moh.Gov.Sa; 2020. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2018-07-30-003.aspx.

30. Samir N, Mohamed R, Moustafa E, et al. 198 nurses’ attitudes and reactions to workplace violence in obstetrics and gynaecology departments in Cairo hospitals. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(3):198–204. doi:10.26719/2012.18.3.198.

31. ALBashtawy M. Workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):550–555. doi:10.1111/inr.12059.

32. Al-Shiyab AA, Ababneh RI. Consequences of workplace violence behaviors in Jordanian public hospitals. Employee Relat. 2018;40(3):515–528. doi:10.1108/er-02-2017-0043

33. Al-Turki N, Afify AA, AlAteeq M. Violence against health workers in family medicine centers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:257–266. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S105407

34. Blando J, Ridenour M, Hartley D, Casteel C. Barriers to effective implementation of programs for the prevention of workplace violence in hospitals. Online J Issues Nurs. 2014;20(1):7.

35. Alqahtani MA, Alsaleem SA, Qassem MY, et al. Physical and verbal assault on medical staff in emergency hospital departments in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. Middle East J Fam Med. 2020;18(2):94–100. doi:10.5742MEWFM.2020.93753.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.