Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 10

The association between stress and acne among female medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Authors Zari S , Alrahmani Dana

Received 7 August 2017

Accepted for publication 6 November 2017

Published 5 December 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 503—506

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S148499

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Shadi Zari,1,2 Dana Alrahmani3

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; 2Adjunct Division of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada; 3Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: Although there is widespread acceptance of a relationship between stress and acne, not many studies have been performed to assess this relationship. The objective of this study was to determine the relationship between stress and acne severity.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 144 6th year female medical students 22 to 24 years in age attending the medical faculty at King Abdulaziz University. This study used the global acne grading system (GAGS) to assess acne severity in relation to stress using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The questionnaire also included some confounding factors involved in acne severity.

Results: The results indicated an increase in stress severity strongly correlated with an increase in acne severity, which was statistically significant (p<0.01). Subjects with higher stress scores, determined using the PSS, had higher acne severity when examined and graded using the GAGS.

Conclusion: On the basis of this study, it is concluded that stress positively correlates with acne severity.

Keywords: acne, acne vulgaris, acne severity, acne grade, stress, stress scale

A Letter to the Editor has been received and published for this article.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a common cutaneous inflammatory disorder affecting more than 85% of adolescents worldwide.1,2 Its pathogenesis is multifactorial. One of these factors is stress, which influences several dermatological disorders.3,4 Seventy four percent of 178 patients and relatives in a questionnaire survey reported that they believed that anxiety is an exacerbating factor of acne.5 An interventional study found that patients had an improvement in their acne compared to controls when receiving biofeedback training, relaxation training, and stress reduction techniques.6

Although there is widespread acceptance of a relationship between stress and acne flares, not many studies have been conducted to assess this relationship. This study uses the global acne grading system (GAGS) to assess acne severity in relation to stress by using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).

Methods

A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study was distributed among 144 6th year female medical students (aged 22–24 years) at King Abdulaziz University Hospital. The Ethics Committee at King Abulaziz University Hospital and the Research Committee at the University of Jeddah Faculty of Medicine approved the study. PSS was used to measure the degree to which the respondents’ external situation is perceived as being stressful with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. This 14-item self-questionnaire is reliable and has been widely used in stress research.7,8 The questionnaire also included some confounding factors in acne severity, such as, menstruation, heat and humidity, sweating, use of makeup and cosmetic products, oily hair products, use of topical steroids, and squeezing pimples. Also, the similar age and sex of the study group eliminates confounding by age or sex.

After providing verbal consent, the 6th year female medical students received the PSS to complete during teaching sessions conducted at King Abdulaziz University Hospital. The two ethics committees approved the verbal consents. There were no exclusion criteria. All participants completed the questionnaire. Upon completion of the questionnaire, an intern who was trained earlier by the consultant dermatologist examined the students for the presence of acne lesions. The trained intern then graded the acne severity and was blinded to the study outcome.

Clinical classification of acne severity was done using the GAGS. The type of acne lesions present (comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules) and their location were noted. The severity of acne was then calculated.9

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 13 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Regression analysis of stress severity and acne severity was carried out by the method of least squares. The analysis of covariance was also used to test whether certain factors have an effect on the relationship between stress as a dependent variable and acne as a covariate among female medical students. In addition, chi-squared test and correlation analysis were performed. p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Using the GAGS, it was found that 3 students (2.1%) had no acne, 104 students (72.2%) had mild acne, 33 students (22.9%) had moderate acne, and 4 students (2.8%) had severe acne.

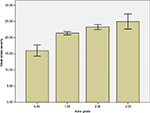

An increase in stress severity was strongly correlated with an increase in acne severity, which was statistically significant (r=0.23; p<0.01). Subjects with higher stress scores, determined using the PSS, had higher acne severity when examined, and acne severity was graded using the GAGS. Figure 1 shows that stress severity increased with increasing acne grade. Of the eight acne aggravators included in the questionnaire, excessive heat and humidity was the only statistically significant aggravating factor (p<0.05%) as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Effects of some factors on the relationship between stress severity and acne severity among female medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (analysis of covariance) |

Discussion

Acne has a high worldwide prevalence rate of 85%.1,2 Although there is widespread acceptance of the relationship between stress and acne flares, not many studies have been conducted to assess this relationship. There is already wide perception that stress aggravates acne. In a study performed in Australia among final year medical students at the University of Melbourne, 67% of students identified stress as an exacerbating factor.10 Also, a multicenter epidemiological study from patients who visited 17 Korean hospitals was conducted. It found that the main triggering factor was psychological stress and was reported by 82% of patients.11

In our study, students with higher stress scores of perceived stress determined by using PSS had a higher acne grade, which was found using GAGS. This positive correlation was statistically significant (p<0.01). Our results go along with two studies done previously which explored this correlation. First, a university study of 22 patients showed that increased acne severity was significantly associated with increased stress levels (r=0.61, p<0.01).12 In the second study in which 94 students in Singapore were enrolled in a prospective cohort study, there was a statistically significant correlation between stress levels and severity of acne (r=0.23, p=0.029).13

Many factors have been implicated as aggravators of acne including blood hormone changes and premenstruation,14 excessive heat and humidity,11,15–17 sweating,1,16,17 use of makeup and cosmetic products,11,18,19 and the use of oily hair products.1,20 Also, the use of topical corticosteroids21–23 and squeezing pimples24 have been known to increase acne lesions. Excessive heat and humidity was the only significant aggravating factor in our study. It is postulated that heat and humidity make it more favorable for Propionibacterium acnes to colonize the ductal hyperplasia.17

There are a number of proposed mechanisms of why stress aggravates acne. In adult women with acne, chronic stress increases the secretion of adrenal androgens and results in sebaceous hyperplasia.25 Activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is the main adaptive response to systemic stress. In response to emotional stress, the HPA axis activates increased levels of cortisol release. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is the most proximal element of the HPA axis. CRH acts as a central coordinator for neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress.26 CRH stimulates sebaceous gland lipid production and steroidogenesis, which contributes to acne.27,28 Studies have also shown an increase of CRH expression in the sebaceous glands of acne-involved skin, compared to a low expression in normal skin.26,29 This upregulation of CRH expression in acne-involved skin may influence the inflammatory processes that lead to stress-induced acne lesions. CRH also induces cytokines IL-6 and IL-11 production in keratinocytes, contributing to inflammation, which is regarded as a key component in the pathogenesis of acne.30

Peripheral nerves release the neuropeptide substance P or vasointestinal peptide in response to stress. Substance P stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of sebaceous glands and upregulates lipid synthesis in sebaceous cells.31,32 Also, psychological stress could delay wound healing up to 40%, which could affect the repair of acne lesions.33,34

Conclusion

Stress triggers or worsens acne by multiple mechanisms. Not many studies have assessed the relationship between stress and acne flares. On the basis of this study, it is concluded that stress positively correlates with acne severity. Therapeutic approaches can be adjusted according to stress levels and behavioral intervention could be an option in some cases.

Acknowledgment

The authors thanks go to Professor Talal Zari for performing the statistical analysis for this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361–372. | ||

James WD. Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1463–1472. | ||

Rodriguez-Vallecillo E, Woodbury-Fariña MA. Dermatological manifestations of stress in normal and psychiatric populations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(4):625–651. | ||

Garg A, Chren MM, Sands LP, et al. Psychological stress perturbs epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis: implications for the pathogenesis of stress-associated skin disorders. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:53–59. | ||

Rasmussen JE, Smith SB. Patient concepts and misconceptions about acne. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:570–572. | ||

Hughes H, Brown BW, Lawlis GF, Fulton GE. Treatment of acne vulgaris by biofeedback, relaxation, and cognitive imagery. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27:185–191. | ||

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. | ||

Linn MW. Modifiers and Perceived Stress Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:507–513. | ||

Doshi A. Zaheer A. Stiller MJ. A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:416–418. | ||

Green J, Sinclair RD. Perceptions of acne vulgaris in final year medical student written examination answers. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42(2):98–101. | ||

Suh DH, Kim BY, Min SU, et al. A multicenter epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Korea. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(6):673–681. | ||

Chiu A, Chon SY, Kimball AB. The response of skin disease to stress: changes in the severity of acne vulgaris as affected by examination stress. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):897–900. | ||

Yosipovitch G, Tang M, Dawn AG, et al. Study of psychological stress sebum production and acne vulgaris in adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(2):135–139. | ||

Williams M, Cunliffe WJ. Explanation for premenstrual acne. Lancet. 1973;2(7837):1055–1057. | ||

Tucker SB. Occupational tropical acne. Cutis. 1983;31:79–81. | ||

Sardana K, Sharma RC, Sarkar R. Seasonal variation in acne vulgaris – myth or reality. J Dermatol. 2002;29(8):484–488. | ||

Belisario JC. Acne vulgaris. Aust J Dermatol. 1951;1:86. | ||

Perera MPN, Peiris WMDM, Pathmanathan D, Mallawaarachchi S, Karunathilake IM. Relationship between acne vulgaris and cosmetic usage in Sri Lankan urban adolescent females. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Epub Sep 22. | ||

Kligman AM, Mills OH. Acne cosmetica. Arch Dermatol. 1970;10:843. | ||

Plewig G, Fulton JE, Kligman AM. Pomade acne. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:580–584. | ||

Fulton JE, Kligman AM. Aggravation of acne vulgaris by topical application of corticosteroids under occlusion. Cutis. 1968;4:1106–1109. | ||

Plewig G, Kligman AM. Induction of acne by topical steroids. Arch Dermatol Forsch. 1973;247:29–52. | ||

Kligman AM, Leyden JJ. Adverse effects of fluorinated steroids applied to the face. JAMA. 1974;229(1):60–62. | ||

Mills OH Jr, Kligman A. Acne mechanica. Arch Dermatol. 1975; 111(4):481–483. | ||

Kligman AM. Post-adolescent acne in women. Cutis. 1991;48:75–77. | ||

Ganceviciene R, Graziene V, Fimmel S, et al. Involvement of the corticotropin-releasing hormone system in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:345–352. | ||

Zouboulis CC, Seltmann H, Hiroi N, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone: an autocrine hormone that promotes lipogenesis in human sebocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(10):7148–7153. | ||

Zouboulis CC, Böhm M. Neuroendocrine regulation of sebocytes – a pathogenetic link between stress and acne. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13(Suppl 4):31–35. | ||

Krause K, Schnitger A, Fimmel S, Glass E, Zouboulis CC. Corticotropin-releasing hormone skin signaling is receptor-mediated and is predominant in the sebaceous glands. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39(2):166–170. | ||

Zbytek B, Mysliwski A, Slominski A, Wortsman J, Wei ET, Mysliwska J. Corticotropin-releasing hormone affects cytokine production in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Life Sci. 2002;70(9):1013–1021. | ||

Toyoda M, Nakamura M, Morohashi M. Neuropeptides and sebaceous glands. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12(5):422–427. | ||

Todoya M, Morohashi M. New aspects in acne inflammation. Dermatology. 2003;206:17–23. | ||

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, Mercado AM, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet. 1995;346:1194–1196. | ||

Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Laskowski BF, Malarkey WB. Stress-related changes in proinflammatory cytokine production in wounds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:450–456. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.