Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

The adaptive problems of female teenage refugees and their behavioral adjustment methods for coping

Authors Mhaidat F

Received 18 June 2015

Accepted for publication 7 December 2015

Published 28 April 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 95—103

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S90718

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Fatin Mhaidat

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

Abstract: This study aimed at identifying the levels of adaptive problems among teenage female refugees in the government schools and explored the behavioral methods that were used to cope with the problems. The sample was composed of 220 Syrian female students (seventh to first secondary grades) enrolled at government schools within the Zarqa Directorate and who came to Jordan due to the war conditions in their home country. The study used the scale of adaptive problems that consists of four dimensions (depression, anger and hostility, low self-esteem, and feeling insecure) and a questionnaire of the behavioral adjustment methods for dealing with the problem of asylum. The results indicated that the Syrian teenage female refugees suffer a moderate degree of adaptation problems, and the positive adjustment methods they have used are more than the negatives.

Keywords: adaptive problems, female teenage refugees, behavioral adjustment

Introduction

Asylum is considered to be a social event or phenomena that usually occur in a historical and political context, which in turn holds in significant negative effects on the communities in general and on individuals in particular. It is considered as one of the worst incidents that the communities were exposed to, which leads to changes in the structure of the new community, in addition to the massive and sudden changes in the lives of refugees.1 Asylum is one of the most difficult life experiences; it may be the only option for saving life because most of those, who decided to abandon their countries, homes, cultures, and civilizations, did that for the purpose of saving their own lives as well as their children.2

Given the negative impacts of asylum on families and children, it is perceived as a negative event and a severe mental shock for all community members. It is also a dangerous event that threatens societies and requires lots of planning and preparation for the tremendous numbers of people who may be forced to leave their home country and move to another country or the interior asylum, seeking security, safety, and rescue. Refugees suffering from mental, social, and family troubles move to different societies because they were exposed to various painful events and experiences such as killings, torture, or loss of family members. These painful experiences are reflected on them and their families, particularly children, either kids or teenagers, who may experience several psychological disorders as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3

The change made by asylum in the lives of kids and teenagers can cause huge psychological difficulties due to changes in daily routine, living in a new strange community, leaving their schools and friends, and living in a poor environment. All these put tremendous pressures on children, so they may face difficulties in adapting, creating feelings of depression and grief, and severe fear of the unknown.4

The problem

This paper seeks to answer the following question:

What is the level of adaptive problems that Syrian teenage female refugees suffer from, and their positive and negative behavioral methods for adapting with asylum?

Research objectives

- What is the level of the adaptive problems that Syrian teenage female refugees suffer from in the government schools within the First Zarqa directorate?

- What are the positive and negative behavioral methods used by the female refugees to adapt with the problems of asylum?

Importance of the study

Identifying the problems that the Syrian teenage female refugees suffer from and their negative behavioral methods for coping with asylum could provide solutions for them and suggest recommendations for coping methods.

Operational definitions

Female Syrian refugee adolescents: the females aged 12–16 years old, who moved to Jordan as a result of war conditions in their home country.

Adaptive problems: the degree the student gets on the scale of adaptive problems prepared for this study.

Adaptation methods: the degree the student gets on the questionnaire of behavioral styles adopted by the female refugee adolescents to cope with their asylum in Jordan.

Theoretical framework

Asylum

The word “refugee” is defined as every person who was forced to leave his/her original homeland in search of shelter, having justifiable fear of being exposed to persecution as a result of racism, religion, nationalism, belonging to a certain social party, or because of political opinion, and being unable to go back because of fear of being exposed to persecution.2

Every year, all around the world, millions are forced to abandon their homes only to join the refugee population.5 Civilians can be targeted by the political violence. Therefore, they have no choice but to escape to other areas or to leave their country for another seeking safety.6

The number of Syrian refugees in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan reached nearly 937,830 people with some of them living in camps and others outside. These huge numbers of human beings, who forcibly left their country in fear of death, torture, and persecution and who need many economical resources and various services within all life domains, forming huge mental, social, and economical burdens to Jordan and also to Syrian refugees.7 According to Ministry of Education statistics, the total number of Syrian refugee students in Jordan was 121,882 (30,476 males and 91,406 females).

Of the total number of Syrian students registered in the government schools within the Zarqa region, 4,873 were male students and 5,834 were female students.

Refugees come from all over the world after being exposed to difficult conditions or experiencing different types of oppression, which in turn reflected on them and their families. Most of those who have experienced asylum as a result of wars suffered from PTSD. This resulted in them showing particular behavioral traits such as suicides, problems with alcohol and drugs, and other psychological troubles. Some of the refugees who were exposed to torture demonstrated mental problems that are more dangerous than those who were not tortured.3

As a result of asylum, families enrolled in the new community become poorer, and the children and adolescents may live with their parents or without them. They live in refugee camps, which are often unsatisfactory because of the harsh troubles and conditions they usually experience inside these camps.1 Refugees and their families, during the initial stages of migration which include leaving their original countries, usually suffer from the difficulty of adapting to and coping with the new culture. Accepting the host country’s culture and leaving the original country’s culture can be a huge shock to the family, making the family members to feel as if they are defeated and broken, and consequently unsafe.8

The family members may face painful situations, such as like being threatened by forceful separation from family or death, physical violence, and torture, leading them to experience PTSD.1 They also experience emotional disorders such as depression, grief, isolation, and withdrawal behavior in addition to the social disorders such as inability to interact with peers, not willing to go to school, as well as psychophysical disorders such as conflict, stomach aches, and other pains.4 The kids who are <8 years old show signs of exhaustion, tiredness, irregular behaviors, increase in hostility, attachment, and depression.8 The most common mental disorder seen in migrants and stricken people is PTSD.9

Adolescence

The term “adolescent” means transition from childhood to adulthood, and it extends between the ages of 13 years and 19 years, 2 years earlier or after 1–2 years (Al-Mtiri, unpublished data, 2007). Adolescence is considered one of the important growth phases, particularly this stage is considered significantly important for the individual’s personal formation, and it may result in troubles for the adolescent and his/her family. Scholars call this stage as the transformational stage.10

Adolescence is characterized by being in the preparation phase for practical life and taking responsibility.11 But the adolescents usually face several difficulties and challenges such as psychological conflicts, social pressures,12 identity crisis,13 confusion, or lack of clarity among parents and teachers regarding concepts such as authority, freedom, and the difference between adults’ and adolescents’ point of view regarding these concepts (Mhaidat, unpublished data, 2011), and choices and decisions, which identify their future life.12

The previously mentioned difficulties and challenges faced by adolescents within normal safe and loving families become more tense and severe when the adolescent finds himself/herself amid a hard experience or a huge mental shock, such as migrating and leaving their original land. Asylum is considered one of the compressing life experiences, leading to several pressure sources such as the decline in the living standard.

Related studies

The study by Dahl et al14 aimed at identifying the shocking events and anticipating PTSDs among the Bosnian refugee women who had left their country. The sample was composed of 209 women, aged 15–70 years old. The result showed that the levels of PTSD were increasing.

Also, Perez et al15 conducted a study for identifying the spreading of PTSD among school children; the sample comprised 493 kids, aged 5–14 years old. The study was done using mental health interviews and PTSD scale. The findings showed that PTSD can spread among children who were exposed to war in a higher degree than those who were not exposed.

In a study conducted by Meis et al,16 a sample consisting of 301 soldiers used the PTSD scale, the social adaptation scale, and the depression scale. The results indicated that there is a relationship between PTSD and the social and mental adaptation disorders, since soldiers were suffering from nightmares, isolation, and sleeplessness.

Ahmad et al17 conducted a study for the purpose of identifying the general features that characterize PTSD among kids living in refugee camps to the north of Darfur. The sample consisted of 5,200 kids and teenagers. The study found that PTSD is the most prevalent disorder.

Uguak18 conducted a study with the aim of identifying the importance of social and mental needs for migrating children who suffer from PTSD in schools and who experienced war in the south of Sudan. The sample contained 235 kids, aged 8–14 years old, and the results indicated that 63 children suffered from PTSD. The study utilized different activities such as games and using theater for treating children, and a clear improvement was achieved.

Methods

Participants

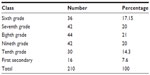

The sample used in this study comprises all female Syrian refugee adolescents enrolled at grades sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, and first secondary within government schools at the First Zarqa Educational Directorate. The sample included 210 female students who were chosen randomly from ten secondary schools as listed in Table 1. This study was approved by Hashemite University human ethics committee. Students who voluntarily agreed to participate were included in the study, and all participants provided informed written consent.

| Table 1 Distribution of the sample according to the class |

Instruments

Adaptive problems measure

After reviewing the previous literature related to the topic of asylum impact on female Syrian adolescents and the adjustment problems they suffer from, in addition to conducting survey interviews with ten female refugees, the researchers found that the most common adjustment problems among the refugee kids are feeling unsafe, anger, depression, and low self-esteem. Based on these, a scale for measuring adaptation problems was created, including four submeasures and using available measures such as the list of adjusted symptoms by Derogatis and others, Lynett’s (1998) measure for controlling anger, Maslow’s measure for feeling safe that was translated to Arabic by Dawani and Deerani (1983), and the self-esteem measure that was developed by Al-Khateeb (Al-Khateeb, unpublished data, 2004).

Data input

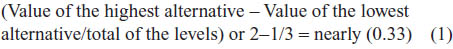

After collecting the study tool from the sample participants, a degree was extracted for each examinee representing the level of their adaptive problems, by translating the answer sheet of the tool items from a verbal scale into a quantitative scale. This was done by giving the answer (Yes) 1 score and the answer (No) 2 scores, then the mean values were calculated for all scores recorded for the items. The degree of having problems was classified according to the averages of the participants’ answers on each item as follows: (1–1.33) low level, (1.34–1.67) moderate level, and (1.68–2) high level, based on the formula:

Then (0.33) was added to (1), it became (1–1.33), which defines the lowest level of the adaptive problems, the moderate level was (1.34–1.67), and the highest level was (1.68–2).

Validity

Face validity by ten specialists in counseling as a jury gave their evaluation about the adaptive problems measure items. The cutting point for accepting any item was 80% agreement among the jury.

The discriminative validity

The t-test for two independent samples was applied on the data of 30 students, outside the study sample, by comparing the difference between mean of the high and low 50%. The t-test results showed a significant difference at 0.000, as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Results of independent samples t-test for independent samples according to high and low groups |

After finding out the significances of validity and reliability for the tool, its items were modified by omitting some and altering others, and the final version contained 94 items.

Reliability

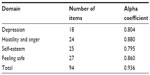

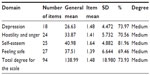

The reliability of the adaptive problems measure for the female Syrian refugees was calculated by using the internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha equation, as shown in Table 3.

| Table 3 Results of alpha coefficient test |

In Table 3, the values of alpha coefficient were high and that means the availability of a high degree of reliability in the tool domains and in it as a whole.

The questionnaire of behavioral adaptive methods

This questionnaire consists of 22 items, including 12 negative and nine positive items. A Likert-type scale was used that includes “always, usually, often, sometimes, rarely, and never”. Five marks were given to “always” and one mark was given to “never”.

Validity

Face validity by ten specialists in counseling as a jury gave their evaluation about the questionnaire items. The cutting point for accepting the items was 80% agreement among the jury.

Reliability

Internal consistency

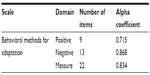

The reliability coefficient of the behavioral adaptive methods questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha equation, as shown in Table 4.

| Table 4 Results of alpha coefficient test |

In Table 4, the values of alpha coefficient were high and that means the availability of a high degree of reliability in the tool domains and in it as a whole.

Data analysis

To achieve the study goals and to answer its questions, SPSS (Version 17.0) was used to carry out the statistical analysis process and reach the targeted goals within the study frame. The significance level 0.05 was accredited that matches a confidence level of 95% for illustrating the tests’ results. The researcher used the following statistical methods:

- Reliability:

Cronbach’s alpha equation was used to test the degree of internal consistency of the tool. - Pearson correlation coefficient:

It was used for measuring the validity of the study tool. - The descriptive statistical analysis:

Some statistical methods related to the scales of central tendency and standard deviation were used, for example:

- Arithmetic mean:

It was used for the participants’ responses on the study questionnaire while answering the first question, where the practicing degree was identified according to the following classification: (1–1.33) low, (1.34–1.67) medium, (1.68–2) high. - Standard deviation:

It was used to measure and reveal the extent of dispersion for the participants’ responses around the mean. The more the standard deviation decreases, the best is achieved. Low standard deviation refers to little dispersion in the answers around the mean. - Frequencies and percentages:

They were used to describe the sample.

Results

To assist in understanding the results of this study, questions have been divided into two types.

Results of the first question

“What is the level of adaptive problems female Syrian refugee adolescents suffer from in government schools within the First Zarqa directorate?”

To answer this question, mean and standard deviations were calculated for the students’ responses on each domain of the four domains of adaptation problems, in addition to the total degree of the scale. Table 5 clarifies the results of this question, noting that the scale used was dual (Yes–No). Levels of adaptive problems based on item mean are (1–1.33) the lowest level, the moderate level (1.34–1.67), and the highest level (1.68–2). Levels of adaptive problems based on general mean are (94–125.20) low, (125.96–156.98) moderate, and (157.92–188) high.

| Table 5 Mean and standard deviations for the students’ responses of adaptation problems |

Table 5 shows that female Syrian refugees perceive themselves to have moderate adaptive problems while attending government schools, where the mean for their responses on the entire items of the scale was 138.99, with a percentage of 73.93% of the sample whose marks were within the moderate category; thus, these adolescents suffer from adaptation problems with a moderate degree, based on the general mean.

To identify the level of these adaptation problems that these female Syrian refugee adolescents suffer from, mean, standard deviations, and percentages were calculated for each item in the four domains: depression, feeling unsafe, hostility and anger, and low self-esteem.

First: depression domain

Table 6 refers to these mean and percentages for each item of the depression domain. It is clear in Table 6 that most of the participants’ responses are around the mean, which indicates a moderate degree, where the number of the medium-degree items was 13 items out of 18, three items indicate the low degree, and two items signify the high depression degree.

Second: hostility and anger domain

Regarding the domain of hostility and anger, its total items were 24. Table 7 shows that there are adaptation problems related to hostility and anger, where the mean of their degrees was 70.56. This mean is located within the medium level of anger and hostility. Table 7 displays the entire degree for each of the domain items.

It is clear in Table 7 that most of the participants’ responses are around the mean, which indicates a moderate degree of problems, where the number of the medium-degree items was 13 items out of 24, while the items that indicate a high degree of anger and hostility were two. Low degrees were represented by nine items.

Third: low self-esteem domain

Regarding the domain of low self-esteem, its total items were 25. Table 8 shows that the mean related to low self-esteem domain was 81.96. This mean is located within the moderate level of low self-esteem. Table 8 displays the degree for each of the domain items.

It is clear in Table 8 that the number of medium-degree items was ten of 25 items, whereas the number of items that scored high level of low self-esteem was 14. On the other hand, only one item was of low level.

Results showed that most answers were around the general mean, and it illustrates that there are moderate problems with low self-esteem domain.

Fourth: feeling unsafe domain

Regarding the domain of feeling unsafe, its total items were 27. Table 9 shows that there are adaptation problems related to feeling safe, where the mean was 69.46. This mean is located within the moderate level.

It is clear in Table 9 that most of the participants’ responses are around the mean, which indicates a moderate degree, where the number of the moderate items was 13 of 27, while only one item indicated a high degree of feeling unsafe was one, and the low were eight items.

The second question

“What are the positive and negative behavioral methods used by the female refugees to adapt and cope with the problem of asylum?”

To answer this question, mean and standard deviations were calculated for the students’ responses on the questionnaire of behavioral methods for adaptation with asylum.

Positive behavioral adaptation methods

Table 10 clarifies the results. It is clear in Table 10 that most of the participants’ responses are around the mean, which indicates a moderate degree of a positive adaptation, where the number of the moderate-degree items was six of nine, while the items that indicate a high degree were two, and one in the low degree.

| Table 10 Mean and percentages for each item of the positive methods |

Negative behavioral adaptation methods

Table 11 shows the results. It is clear in Table 11 that most of the participants’ responses are in the low level, which indicates that less negative methods are used by the participants, where the number of the low-degree items was eleven of 13, and one item for each of the moderate and high level. This result confirms the results showing that positive methods are used by the participants to help cope with their refugee problems.

| Table 11 Mean and percentages for each item of the negative methods |

Discussion

Results related to the first question

What is the level of adaptation problems that female Syrian refugee adolescents suffer in government schools within the First Zarqa area?

Findings indicate that the female refugee adolescents suffer from adaptation problems in a level of 73.93% on the whole scale and regarding the subdimensions as following: depression, 73.97%; hostility and anger, 70.56%; low self-esteem, 81.96%; and feeling unsafe, 69.46%. This result agrees with the study by Burnett and Peel,4 which pointed out that refugees suffer from huge pressures, creating the feelings of depression, grief, and severe fear from the unknown. War experiences are considered to be harsh and painful, such as death threats, witnessing death, torture, or being threatened by it. Other experiences such as destruction of homes, losing sources of income, and insecurity because of their homes being raided day and night make the people extremely afraid. It also agrees with the study by Kantemir3, which showed that kids and adolescents who experienced asylum and were exposed to torture events suffer from severe mental disorders as well as PTSD. It also agrees with the study by Saidoom and Thabet,19 which showed that the university students in the Gaza Strip suffer from severe shocks and variations in their mental health such as worry and depression due to the location of universities near areas of bombing and destruction, which causes a fear for their lives. These results again support the study by Skotnicka,20 which was conducted on the Polish soldiers after coming back from the Iraqi war, where it was found that the soldiers who experienced the war were having a high level of anger, suffering from physical–mental disorders such as exhaustion, increase in heart rate, and tiredness.

Results related to the second question

What are the positive and negative behavioral methods used by the female refugees to adapt with the problems of asylum?

The study found that the most used behavioral methods among the female refugees were the positive adaptation ones, where the item (I practice sportive exercises) got the highest responses, in addition to the item (working after formal hours). This may be ascribed to the fact that the sample contained females who usually act away from negative adaptation methods, in addition to the large sympathy and wide acceptance refugees got from the schools’ teachers and administrators. Moreover, there were the educational consultants who were qualified within the government schools through passing experimental courses for dealing with kids of crises in order to help this class of people in emotional expression and self-expression. These results match the ones achieved by Nahla’s study,21 which revealed that the female Palestinian refugees were forced to work and get out of school in order to help carry out family affairs and to get a financial income for the family. Fleeing one’s native country creates a new burden in the new country, providing food and shelter, as well as providing school requirements, which makes asylum a new cause of stress and pressure. In addition to the enormous psychological difficulties that refugees suffer as a result of their flight from war, witnessing terrifying sights and experiencing many scenes of violence, murder, and destruction, many refugees are forced to quit school and work full-time or part-time jobs, especially males. Syrian families in Jordan rely on foreign aid that are not sufficient to cover the family’s needs. Therefore, Syrians resort to working part-time jobs, which causes them to lose job stability and most of them are of school-going age yet do not attend. These results contradict the findings of Kantemir’s study,3 which showed that many refugee children and adolescents tried suicide, having problems in using alcohol and drugs. Many refugees may resort to drugs to lessen the effects of psychological stress of war and life-threatening experiences and the difficulty to adjust in the new country. That may not apply to this study, because it was conducted on teenage girls in government schools, which often enforce good behavior, obedience, and morality. Based on what the study came up with, I recommend the following:

- Conducting more studies that involve refugee families.

- Using cognitive behavioral remedy programs for easing the impact of asylum on kids and adolescents.

- Providing teachers and educational consultants with training programs for dealing with kids suffering from crises.

- Providing families of refugees with training programs to help develop their skills for coping with new situations.

The limitations of the study

- The sample of the study was restricted to female Syrian refugee adolescents in government schools within the First Zarqa region only.

- The sample included the female Syrian refugee adolescents within the age group 12–16 years old, so the results will be limited to this class of students.

- The results of the study will be identified by the tools used as well as the procedures implemented to examine their validity and reliability.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Marina AJ. Impact of displacement on the psychological well-being of refugee children. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1998;1998(10):186–195. | |

Lipson G. Afghan refugees in California: mental health issues mental health issues. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1993;14(4):411–423. | |

Kantemir E. Studying torture survivor: An Emerging Field in Mental Nursing. JAMA. 1994;272(5):411–423. | |

Burnett A, Peel M. Health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. Br Med J. 2001;322:544–547. | |

Forster BA. A statistical overview of displaced persons. Natl Soc Sci J. 2010;17(1):38–44. | |

Schmidt M, Kravic N, Ehlert U. Adjustment to trauma exposure in refugee, displaced, and non-displaced Bosnian women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(4):269–276. | |

UN General Assembly, Executive Committee of the Program of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Summary record of the 682nd meeting (A/AC.96/SR.682), 2014. http://www.unhcr-arabic.org/pages/4be7cc278c8.html. Accessed June 18, 2015. | |

Briskman L, Goddard C. Australia traffics and abuses asylum seeker children. Comment Age. 2014;4:376. | |

Sa’da M. A Seminar in the Course of Psychological War. [dissertation] Damascus: Damascus University, Psychology Department; 2003. | |

Al-Nayyal M. A Recent Study in Adolescence. Part 2. Amman: Arab Knowledge Company; 2008. | |

Rice F. Human Development. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1992. | |

Zahran H. Growth Psychology “Childhood and Adolescence”. Beirut: Books World; 1985. | |

Gerow RJ. Psychology: An introduction. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publisher; 1992. | |

Dahl S, Mutapcic A, Schei B. Traumatic events and predictive factors for posttraumatic in displaced Bosnian women in a war. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(1):137–145. | |

Perez OI, Fernandez P, Rodado F. Prevalence of war-related post-traumatic stress disorder in children from Cundinamarca, Colombia. Revista de salud Publica. 2005;7(3):268–280. | |

Meis LA, Erbbes C, Polusny M. Dyadic adjustment and PTSD symptoms among OIF veterans: symptoms clusters and pre-to post-deployment functioning. In: Abstract of 27th VA Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) National Meeting February 11–13, 2009; Baltimore, MD. Abstract No.1040. | |

Ahmad A, Okasha A, Abd Al-Majeed AM. Post-shock disorder among kids and adolescents in the displaced camps in West Darfur. Afr Stud J. 2012;46(1):241–289. | |

Uguak UA. The importance of psychological needs for the post-traumatic stress disorder and displaced children in schools. J Instr Psychol. 2004;37(4):340–351. | |

Saidoom R, Thabet A. Disorders of post-shock event from an Arabian perspective. Arabic J Psychol Sci. 2012;3(2):5–24. | |

Skotnicka J. Stabilization mission in Iraq, the individual symptoms of PTSD and a comparison of level of depression, anxiety, and aggression among soldiers returning from the mission and soldiers that stayed in Poland, archives of psychiatry and psychotherapy. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2012;49(5):689–702. | |

Nahla A. Nationalism and feminism: Palestinian women and the intifada – no going back? In: Valentine M, editor. Gender and National identity: Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. London and Atlantic Highlands, NJ/Karachi: Oxford University Press; 1994:148. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.