Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 10

Thai women’s experiences of and responses to domestic violence

Authors Chuemchit M , Chernkwanma S , Somrongthong R, Spitzer DL

Received 3 May 2018

Accepted for publication 25 July 2018

Published 27 September 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 557—565

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S172870

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Montakarn Chuemchit,1 Suttharuethai Chernkwanma,1 Ratana Somrongthong,1 Denise L Spitzer2

1College of Public Health Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Patumwan, Bangkok, Thailand; 2Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Purpose: Domestic violence has been linked to many health consequences. It can impact women’s mental, physical, sexual, and reproductive health, and all of these effects can be long lasting. Despite the growing awareness of the deleterious effects of domestic violence in Thailand, there have been few nation-wide studies that have examined the issue and its consequences. In fact, Thailand has not examined intimate partner violence incidence for the past 20 years. This study aimed to investigate the consequences of domestic violence across the country.

Subjects and methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in four areas of Thailand: central, southern, northern, and northeastern. One province in each area was selected by simple random sampling techniques. One thousand four hundred and forty-four married or cohabiting females in a heterosexual union, aged 20–59 years, were included in the sample and were interviewed about their experiences of psychological, physical, and sexual violence by their male partners.

Results: One thousand four hundred and forty-four women completed the interviews. Sixteen percent of respondents encountered domestic violence in its various psychological, physical, or sexual forms. In the majority of cases, all forms of domestic violence were exerted repeatedly. Four-fifths of women who faced domestic violence reported that it had an impact on their physical and mental health as well as employment. This study also found that half of the domestic violence survivors reported their children had witnessed violent situations. These women exercised four coping strategies to deal with their domestic violence: 1) counseling; 2) requesting help from others; 3) fighting back; and 4) running away from home.

Conclusion: The findings confirm that domestic violence has implications that extend beyond health and result in the deterioration of the quality of women’s lives. These results underscore that domestic violence is a serious problem that must be addressed in Thai society.

Keywords: domestic violence, intimate partner violence, Thailand, prevalence, consequences, violence countrywide, health impact, coping strategy

Introduction

Domestic violence is a global problem1 and a serious public health issue worldwide.2 The WHO defines domestic violence as any act of violence including emotional abuse, physical abuse, and/or sexual abuse between people who are in an intimate relationship.3 The other technical terms used in the scientific literature are intimate partner violence, battering, or wife abuse.4

In terms of its public health effect, domestic violence contributes to emotional, physical, and/or sexual health problems. Many studies have found that abused women experience short- and long-term health and social impacts.2,5 For example, in terms of mental health, researchers have found that domestic violence is associated with expanded levels of depression and suicidal behaviors.6 With regards to physical health and sexual health problems, many studies have discovered that women who faced partner violence are more vulnerable to HIV infection.7,8

As in many Asian countries and across the globe, domestic violence in Thailand is viewed as a private issue or an internal family affair.5 Couples learn to keep quiet and refrain from sharing relationship conflicts with outsiders; resultantly, domestic violence is swept under the carpet and remains a hidden issue in Thai society. Most abused Thai women have to manage and resolve intimate partner violence problems in their lives alone.9 The magnitude of the domestic violence problem in Thailand is underestimated and has rarely been documented. Until recently, most of the domestic violence data in Thailand are documented by government organizations, such as the One Stop Crisis Center (OSCC) – a unit in government hospitals designed to assist victims of crises or other violent situations, police organizations, or by non-government organizations such as individual women’s shelters or women’s organizations.9 The numbers of domestic violence cases reported by the Ministry of Public Health between 2010 and 2013 significantly increased from 25,767 to 31,866.10,11 Furthermore, in 2015, one hospital-based OSCC in Bangkok reported receiving an average of 66 women cases per day.12 While most research to date has illuminated specific issues or geographic areas, there are significant gaps in our knowledge of domestic violence in Thai society as there are no specific studies on the issue nation-wide. The latest research on domestic violence and women’s health in Thailand was conducted in 2003 as part of a WHO-sponsored multi-country study.9 Data in Thailand were collected in two settings – a large urban center and a rural area.9

Our current understanding of how Thai women face domestic violence and how the health effects of partner violence are manifest has been drawn mainly from the OSCC report. This study aimed to 1) examine the prevalence of domestic violence in Thailand; 2) identify the association between the experience of violence and controlling behaviors by the male partner; and 3) investigate the consequences of domestic violence toward Thai women and problem-solving methods in order to understanding how Thai women confront, pass through, and survive intimate partner violence. Such knowledge will be helpful in designing services and intervention that serves women’s needs.

Subjects and methods

Participants

This study was conducted in four areas of Thailand: central, southern, northern, and northeastern. A multi-stage sampling technique was used. Firstly, simple random sampling was used for choosing one province in each area: central (Chonburi province, n=425), southern (Surat Thani, n=230), northern (Phitsanulok province, n=284), and northeastern (Khonkaen province, n=505). Secondly, all districts were selected for the study and the sample was calculated as being proportionate to the size in each province and district. Lastly, convenience sampling was used to choose the respondents in each district site. At the district level, the research team met a community leader in order to ask for the name list of married or cohabiting women and their addresses. After that, the researchers visited their houses based on the list in order to collect the data. All women who fit into the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were selected as respondents. One thousand four hundred and forty-four married or cohabiting heterosexual women aged 20–59 years were included in the study.

Data collection

In each area, the interviews were conducted by trained interviewers who worked in the area of public health and who were experienced in community-based research. All interviewers were trained in the delivery of the questionnaire and in interview techniques and skills, and were given further education on issues pertaining to gender and violence, cultural and interpersonal sensitivity, and research ethics. Face-to-face interviews were conducted following the “gold standard”13 – meaning that data collection focused on safety and confidentiality concerns and was carried out in a private setting by a trained female interviewer. Broad invitations and open questions pertaining to general information and overall health were used at the onset of the interview to make the respondents feel less anxious in responding to questions. The interviewer then posed questions relating to their conjugal relationships, which were followed by queries that asked them to identify specific violent acts of abuse – psychological, physical, and/or sexual – by their male partners. Participants could stop, pass on questions, or terminate the interview at any time. When finished, participants were provided with a booklet that included information about public health services in each area, for instance, hotline numbers and OSCCs. If requested, interviewers also updated the respondents about further support from local health authorities.

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Subjects, Health Science Group, Chulalongkorn University (COA No 158/2017), Thailand.

Measurement tool

The questionnaire consisted of three parts: 1) general information; 2) relationship and partner violence experiences; and 3) consequences of, and strategies for dealing with, partner violence. The survey was based on the WHO questionnaire on domestic violence and women’s health.9,14 In the second section, experiences of partner violence were categorized as: 1) psychological (insulting, humiliating, scaring, and threatening); 2) physical (slapping or throwing, pushing or shoving, hitting, kicking or dragging, choking or burning, and threatening to use weapon); and 3) sexual (physically forcing a woman to engage in sexual activities, compelling sexual activity against a woman’s will, and forcible sexual humiliation). For each act of violence, respondents were asked about the timing (within the past 12 months) and then about the frequency of each act (once or twice, a few times, or more than five times). Furthermore, interviewees were asked about seven forms of controlling behaviors that may have been exhibited by their male partners. For each controlling act, each participant was asked whether it had occurred within the past 12 months (Yes or No). “Yes” answers were assigned a score of one and “No” answers were assigned a score of zero. The maximum possible score was seven. Total scores were categorized into four levels:14 1) none (score of zero); 2) low (score of one); 3) medium (scores of two to three); and 4) high (scores ranging from four to seven). In the final section, women were asked the following: about their perspectives regarding the precipitating circumstances for violent episodes, whether children were witnesses to violent situations, if and how they felt intimate partner violence affected their health and/or daily life, and to describe their health, support-seeking, and coping strategies. The pre-test was done and the Cronbach’s alphas for part two and part three were 0.94 and 0.88 respectively.

Data analysis

Data were entered into the SPSS (Version 21). Univariate and bivariate analyses were used in this study. Univariate analysis – frequencies and percentages – was used to explain and conclude variables and examine the patterns in the data. Bivariate analysis was used to find out whether there was an association between the variables.

Results

The majority of the respondents were 40–49 years of age and the mean age was 39.5 years. Most of the women (33.8%) had completed higher education, and the rest had finished high school, primary education, and secondary education, respectively. Ten percent of the respondents were housewives, while 90% were employed outside the home. Nearly 32% of the study population stated that their incomes were insufficient to cover household expenses, while a little over half (52.4%) reported sufficient household earnings, but had no savings. Nearly 50% of women earned wages that were equal to or above that of their male partners. The majority of the respondents (69.7%) had one to two children (see Table 1).

| Table 1 Selected sociodemographic characteristics of married/cohabiting women (N=1,444) |

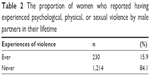

According to this study, nearly 16% of the 1,444 married or cohabiting women faced various forms of psychological, physical, or sexual violence by their male partner, suggesting that 1 in 6 of Thai women cohabiting in a heterosexual relationship encountered domestic violence experience in their lifetime (see Table 2).

| Table 2 The proportion of women who reported having experienced psychological, physical, or sexual violence by male partners in their lifetime |

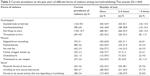

Table 3 shows the percentage of Thai women in the sample who reported experiencing some form of domestic violence within the past 12 months. The study found that of the 1,444 women, 30.8% had experienced some form of psychological violence. The most common form was being made to feel frightened or scared (10.7%), followed by being insulted or made to feel bad (8.5%), being humiliated or belittled (6.8%), and being threatened with physical violence (4.8%). Most respondents contended with repeated acts of domestic violence. Additionally, 5.6% had been pushed or shoved by a male partner and 5.1% had been slapped or had something thrown at them. Among the incidences of sexual violence, 6.7% of the respondents reported unwanted sexual intercourse and 3.6% were physically forced to engage in sexual activities. In the majority of cases, all forms of domestic violence were exerted repeatedly.

| Table 3 Current prevalence (in the past year) of different forms of violence among married/cohabiting Thai women (N=1,444) |

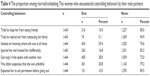

Tables 4 and 5 illustrate the proportion of women among the respondents who had experienced controlling behaviors by their partners and highlight the association between the experience of partner violence and forms of controlling behaviors. The most commonly reported controlling behavior used by male partners was “insisting on knowing where you were at all times”, whereas the least frequently claimed behavior was “trying to prohibit you from contacting your family”. The percentage of respondents who disclosed less or more level of acts of controlling behaviors by male partner varied from 13.5% to 37.0%, which suggests that the level of controlling behaviors over female behavior is normative to distinct degrees. Women who faced domestic violence were significantly more likely to have undergone controlling behavior by the partner than the women who had not encountered domestic violence in their lifetime.

| Table 4 The proportion among married/cohabiting Thai women who encountered controlling behaviors by their male partners |

| Table 5 The association between experience of violence and controlling behavior level by the male partner |

Table 6 shows the consequences of domestic violence. The study revealed that four-fifths of women who had experienced domestic violence reported deleterious impact on their physical and mental health. Furthermore, three-tenths reported they were forced to have sexual intercourse after fighting or arguing. Forty-six percent of abused women reported being injured due to intimate partner violence. When examining the types of injuries, most of the respondents had scratches/bruises (74.8%), followed by sprains (56.1%) and cuts/bites (15.9%). Some informants mentioned serious injuries including broken eardrums or eye injuries (11.2%), broken bones or teeth (6.5%), and burns or deep cuts (6.5%). Three-tenths of women surviving abuse and getting physically injured had been admitted to the hospital as an in-patient. Notably, the women in this study also stated that their encounters with intimate partner violence had an impact on their work, with 61% of the 230 abuse survivors noting that they had difficulty concentrating on their work. Some revealed they lost confidence and developed low self-esteem; some stated they took medical leave as they felt too ashamed to appear at work. A minority of this subsample said they were stalked by their partners, and half of the abused women affirmed that their children had witnessed domestic violence.

| Table 6 Consequences of domestic violence (n=230) |

Table 7 reflects the coping strategies and solving measures. The study showed four methods of coping strategies as follows: 1) counseling, 2) requesting help from others, 3) fighting back, and 4) running away from home. We found that after some violent situations, 21.3% of women who had experienced domestic violence told nobody about their violence because they had no one to tell or share it with, whereas 90.8% shared their experiences with their own parents, siblings, or cousins on some occasions. Nearly 32% approached their friends, 14.3% spoke with neighbors, and 13.9% talked to their children after some violent episodes. A few mentioned they spoke with non-family members such as health care providers (6.1%), police officers (4.3%), and women’s organizations or shelters (1.7%). Regarding seeking outside help and protection, it was found that nearly 80% (77.8%) of abused women disclosed no one was helping them to improve the situation. When considering the reasons why they did not ask for any help, nearly half of them reported being too embarrassed and ashamed (49.7%), while others were unaware of the sources of support (44.7%). Approximately 20% of those who did not seek outside help believed that domestic violence is normal. A few stated they refrained from engaging support due to the fear that something worse might happen, that the relationship would end, and/or that they would lose their children. Three-tenths of the abuse survivors fought back against their partners. After fighting back, nearly 60% reported experiencing escalating violence, whereas 32% stated the violence had either decreased or ceased. Only 8% disclosed that nothing changed in their domestic violence situation. The last coping strategy was running away from home and we found that three-tenths of abused women chose this method to resolve this issue. The respondents who never ran away mentioned four main reasons including beliefs that their partner would change, commitment to the sanctity of marriage (such that one should not separate or divorce), being convinced by their family to return, and/or being worried about their children.

| Table 7 Problem-solving methods (n=230) |

Discussion

This study examined domestic violence among a nation-wide sample of Thai women in heterosexual conjugal relationships to investigate the frequency, types, and consequences of domestic violence in terms of impact and coping strategies employed by women who experienced abuse. The study findings show that a significant number of Thai women have experienced lifetime domestic violence. Nearly 16% of married/cohabiting women surveyed around Thailand had encountered various acts of psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence by their male partner. In addition, in the majority of cases, all forms of domestic violence were exerted as repeated acts. Our findings revealed that male perpetrators in domestic violence showed higher rates of controlling behaviors than those who did not perpetrate their female partner, which is consistent with a WHO multi-country study report of 200614 showing that controlling behaviors by male partners were significantly associated with domestic violence. Consequently, male involvement and de-emphasizing traditional gender norms are important to diminish the rates of domestic violence in Thai society. However, future research focusing on this important concept, that is, male controlling behaviors and their association with domestic violence, may consider using a different validated measure of controlling behavior, as the current study only focuses on seven forms of controlling behaviors that consist of various ways to control women’s daily life activities.

When considering the forms of violence, we found that psychological violence and physical violence were highly more prevalent than sexual violence. These findings are inconsistent with the WHO findings14 showing that in Thailand, sexual violence was more prevalent than physical violence.9,14 The difference between these results could be due to the impact of policies and campaigns on domestic violence protection that Thailand has launched over the past 10 years. For example, until it was amended in 2007, the criminal law B.E. 2550 section 276 stated that “any person who commits sexual intercourse with a woman who is not his wife, and against the latter’s will, by threatening her, or doing any act of violence…, shall be punished with imprisonment….”15 However, changes to the law, which entailed eliminating the phrase “with a woman who is not his wife”, acknowledge that marital rape is a crime and affirms that spouses are legally protected against sexual violence by their partner.16 In addition, in 2007, Thailand launched the “Victims of Domestic Violence Protection Act, B.E. 2550”.17 Furthermore, the government and public agencies released a mass media campaign to promote the cessation of domestic violence. All of these tools may have contributed to a decrease in intimate partner violence in the past decade. Nevertheless, at present, domestic violence prevention campaigns are hardly seen in mainstream Thai culture.

Our findings confirm that domestic violence leads to physical and mental health problems. Women who had experienced physical violence often had various injuries.2,9,18 Among this group of women, about three-tenths went to a professional for medical treatment, with some still hiding the causes of their injuries. Research of Archavanitkul et al has shown that the one reason Thai women did not seek professional treatment is because they did not want to disclose the causes of their injuries to physicians or nurses.9 Societal attitudes such as victim-blaming and refraining from speaking about private problems are still common in many countries across the globe.5,18,19 The dichotomy between private and public in Thai society is particularly salient when it comes to reporting incidences or seeking help for the sequelae of domestic violence. These beliefs and norms can make Thai women feel too embarrassed to speak out about their experiences with domestic violence.

Consistent with many studies,20–22 domestic violence not only affects health, but also impacts other aspects of life including employment and the well-being of children who witness violence. Children who are exposed to their parents’ violence may become fearful and anxious; they may always feel the need to be on guard, watching and waiting for the next event to occur. Because of this these children are always worried about the safety of themselves, their mother, and their siblings, and also may feel worthless and powerless. Many studies reported that women who faced domestic violence also confront employment problems such as loss of concentration at work and needing to take sick leave or days off because of injuries or shame.18,23,24 The survivors in this study disclosed intense feelings of fear, distress, anxiety, and suffering as a result of intimate partner violence. In addition, the results showed that some had problems at work, such as missing work, starting late or leaving early, as well as loss of confidence and low self-esteem.

Half of the women (49.6%) experiencing domestic violence revealed that their children witnessed violence, which may lead to negative impacts. Witnessing family violence is associated with severe effects on children’s health and development.25 These effects range from various forms of behavioral disorders and psychological distress to problems with social development and social interaction.26,27 Women whose children have seen their abuse often express anxiety as they fear their sons will become perpetrators and their daughters will become victims.22,26,28 Witnessing parental violence is significantly associated with increased risk for violence perpetration and/or the perception that domestic violence is normal.29,30 Women who witness domestic violence are three times more likely to repeat the cycle of violence in adulthood.5 The strong association highlights the potential importance of interventions programs to prevent child abuse and children witnessing violence by their parents,22,31 especially community-based measures, for example, enhancing a monitoring and supporting network in the community to ensure women can easily access effective services. Family and community members must be encouraged to intervene in domestic violence situations and offer assistance. Men must be motivated to collaborate at all levels of activities.

Regarding the need for protection and support, this study showed that women experiencing domestic violence had four main coping strategies: 1) counseling, 2) requesting help from others, 3) fighting back, and 4) running away from home. Most survivors chose to talk to their own family and relations for practical and emotional support in coping with domestic violence as they did not want to share with outsiders due to shame, fear, or concern about potential untoward results. However, this study found that more than half of the abused women surveyed did not seek help of any kind. This result also confirms the beliefs and norms toward domestic violence in Thai society. Nearly half of the abused respondents did not have any information about support agencies, which reflects inaccessibility to services or the lack of publicity of related organization, even though there are services available in all regions. Thirty percent of abused women ultimately dealt with violence perpetrated by their partners by fighting back or leaving their home. However, most of the respondents who left home eventually returned to their conjugal household. The high pressure and negative attitude of Thai society toward divorce or even separation may affect women’s decision. These findings are consistent with those reported in the Netherlands by Pels et al, who noted that barriers to help-seeking are grounded in women’s experiences and enculturation, including their desire to avoid hurting their family’s name, pressure from their own family to remain in the relationship, and women not knowing where they could ask for help.22

This study was conducted based on self-report, which may lead to the respondents’ bias and willingness to report their domestic violence problems, as in the Thai society, domestic violence is still perceived as a private issue or an internal family matter. However, this study used a standardized questionnaire that identified specific acts of violence, performed pretesting, used well-trained female interviewers, and also collected data following strictly the ethical guidelines, all of which should have reduced bias and enhanced disclosure from all respondents. However, a qualitative study is needed to further explore how Thai women encounter, pass through, and survive from domestic violence, in order to reflect women’s voices, what they really want and need.

This study was conducted in four regions of Thailand. Simple random sampling was used for the selection of one province in each region. Although the sample was calculated proportionate to the size of each province, this study cannot make inferences about the broader population of Thai women who did not participate in this research. It is recommended that in future, the researcher should be more concerned about using a sample methodology to support a truly representative sample of domestic violence in Thailand.

Conclusion

Our findings emphasize that Thailand has the high prevalence of domestic violence and suggests that domestic violence has a significant impact on many dimensions of women’s lives. The government is positioned to highlight domestic violence and work to stop violence against women in a national policy agenda that could be implemented through all public sectors, particularly in the educational system. Actions at the policy and practice levels are urgently required. The national policy level should aim at eradicating the root of domestic violence and re-building the Thai society as a violence-free zone. For instance, the government needs to provide services to serve women’s needs; the services should include treatment, counseling, shelter, and referrals for further support. Training should be given for multidisciplinary practitioners on issues regarding gender sensitivity and violence against women. Eventually, employers could be involved in learning more about recognizing and accommodating people who are dealing with domestic violence. Also, the heightening of a social campaign over the mass and social media to eliminate all forms of partner violence is needed. Moreover, we have to challenge the social beliefs and social norms to confirm that partner violence is a public concern rather than a private issue, and build community participation by teaching people how to be allies and support for people who experience violence and how/when to intervene when appropriate. We must also train and install competent authorities to ensure effective service delivery to victims of domestic violence. Family members must be encouraged to intervene in situations of violence and provide assistance. Men must be urged to participate in activities at all levels. Another key issue is increasing the public relations and information of existing services in order to encourage abused women to use the specialized services available and also to communicate and disseminate information about these programs to police, health practitioners, and community leaders, so that they can refer women to the appropriate interventions. Finally, various media should be deployed to encourage gender equity and non-violent relationships in Thai society, such as avoiding reproducing structural and cultural violence against women in media reporting by not producing contents that reinforce and motivate violence and also supporting contents that advocates gender equality and respect of human dignity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend a huge thank you to everybody who was involved in this project. Contributions made by all participants are honestly appreciated. This research project is supported by Chulalongkorn University and the Thailand Research Fund.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Devries KM, Mak JY, García-Moreno C, et al. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–1528. | ||

Garcia-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stockl H, Watts C, Abrahams N. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization; 2013. | ||

Krug Eg MJ, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;9339:1083–1088. | ||

Krantz G, Garcia-Moreno C, Garcia MC. Violence against women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(10):818–821. | ||

Mohamad M, Wieringa S. Family ambiguity and domestic violence in Asia: reconceptualising law and process. IIAS Newsletter. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam; 2014:21–23. | ||

Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001439. | ||

Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. | ||

Kouyoumdjian FG, Calzavara LM, Bondy SJ, et al. Intimate partner violence is associated with incident HIV infection in women in Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27(8):1331–1338. | ||

Archavanitkul K, Kanchanachitra C, Im-em W, Lerdsrisuntad U. Intimate Partner Violence and Women’s Health in Thailand. Nakhonprathom, Thailand: Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University; 2005. | ||

Thai Health Promotion Foundation. Situation of violence against women and child: one stop crisis centre of Ministry of Public Health; 2011. Available from: http://www.thaihealth.or.th/healthcontent/news/18221. Accessed August 25, 2011. | ||

The Women’s Affairs and Family Development. Report on Violence Health. Bangkok, Thailand: Thai Health Promotion Foundation; 2013. | ||

The Women’s Affairs and Family Development Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. Report on Intimate Partner Violence Situation. Bangkok, Thailand. 2015. | ||

Garcia-Moreno C, Heise L, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Watts C. Violence against women. Science. 2005;310(5752):1282–1283. | ||

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH, WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269. | ||

Penal Code Amendment Act (No.16) B.E. 2546 (2003). Royal Thai Government Gazettee, 120, 4a 1. Bangkok, Thailand: Royal Thai Government; 2003. | ||

Penal Code Amendment Act (No.19) B.E. 2550 (2007). Royal Thai Government Gazettee, 124, 56 a, 1. Bangkok, Thailand: Royal Thai Government. 2007. | ||

Royal Thai Government Gazette, 41 a, 1. Victims of Domestic Violence Protection Act, B.E. 2550. Bangkok, Thailand: Royal Thai Government; 2007. | ||

Alsaker K, Moen BE, Baste V, Morken T. How has living with intimate partner violence affected the work situation? a qualitative study among abused women in Norway. J Fam Violence. 2016;31:479–487. | ||

Alsaker K, Moen BE, Baste V. Employment, experiences of intimate partner violence, and health related quality of life. J Couns Psychol. 2009;1(4):60–63. | ||

Hedtke KA, Ruggiero KJ, Fitzgerald MM, et al. A longitudinal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(4):633–647. | ||

Rodríguez M, Valentine JM, Son JB, Muhammad M. Intimate partner violence and barriers to mental health care for ethnically diverse populations of women. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(4):358–374. | ||

Pels T, van Rooij FB, Distelbrink M. The impact of intimate partner violence (IPV) on parenting by mothers within an ethnically diverse population in the Netherlands. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(8):1055–1067. | ||

Rothman EF, Hathaway J, Stidsen A, de Vries HF. How employment helps female victims of intimate partner violence: a qualitative study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;12(2):136–143. | ||

Postmus JL, Plummer SB, Mcmahon S, Murshid NS, Kim MS. Understanding economic abuse in the lives of survivors. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(3):411–430. | ||

Pernebo K, Almqvist K. Young children exposed to intimate partner violence describe their abused parent: a qualitative study. J Fam Violence. 2017;32(2):169–178. | ||

Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, Martinez-Torteya C. PTSD symptoms in young children exposed to intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2013;19(2):187–201. | ||

Bernstein RE. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents: scientific foundations and therapeutic models. Ford JD, Courtois CA, editors. J Trauma Dissociation. 2014;15(5):607–610. | ||

Autry A, Davis L, Mitchell-Clark K. Conversations with Mothers of Color Who Have Experienced Domestic Violence Regarding Working with Men to End Domestic Violence. San Francisco: Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2003. | ||

Mallory AB, Dharnidharka P, Deitz SL, et al. A meta-analysis of cross cultural risk markers for intimate partner violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31:116–126. | ||

Hungerford A, Wait SK, Fritz AM, Clements CM. Exposure to intimate partner violence and children’s psychological adjustment, cognitive functioning, and social competence: a review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17(4):373–382. | ||

Heise L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2011. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.