Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Ten steps to plan, design, and implement an endocrinology and endocrine surgery module for the Faculty of Medicine, Al-Baha University

Authors Elfakey WEM , Al-Ghamdi AH

Received 19 May 2016

Accepted for publication 25 August 2016

Published 27 October 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 617—622

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S113144

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Walyeldin EM Elfakey,1,2 Ahmed H Al-Ghamdi,1

1Pediatrics Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Baha University, Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia; 2Pediatrics Department, University of Bahri, Khartoum, Sudan

Introduction: The Faculty of Medicine, Al-Baha University (FMBU), is a newly established medical school that implements a community-oriented and integrated system-based curriculum which is suitable for both medical students and serving the needs of the local community.

Objective: The aim of this study is to describe the steps that were followed to plan, design, and implement an endocrinology and endocrine surgery module (EESM) for the fourth-year medical students, as an example of how system-based modules are designed at FMBU.

Methods: Ten questions based on Harden’s methodolgy were asked in order to design, plan, and implement an endocrinology and endocrine surgery module. The module committee determined the needs of the module and accordingly stated the aims and objectives of the module. The module planners selected the relevant contents, teaching methods, and assessment strategies and organized them.

Results: After addressing each of the ten questions, the results indicated the need, aim, objectives, and contents for the endocrinology and endocrine surgery module at FMBU. The implementation strategies were chosen according to the SPICES model. The teaching methods and the assessment strategies were selected and arranged. The module is well communicated at all levels, and the module committee used every effort to create a productive teaching environment. The module is well managed and follows the hierarchy of FMBU.

Conclusion: Implementing Harden’s ten steps methodology resulted in an integrated module of endocrinology and endocrine surgery where related disciplines and systems were merged and medical and surgical endocrine topics were included.

Keywords: endocrinology, endocrine surgery, module, curriculum

Introduction

The Faculty of Medicine, Al-Baha University (FMBU) was established in 2008. It adopts a fully integrated system-based curriculum. This is applied in three phases, namely the premed phase (phase I), preclinical phase (phase II), and clinical phase (phase III). There is a new level of integration in which all disciplines related to the respective system are merged into one module. In this endocrinology and endocrine surgery module (EESM), both medical and surgical endocrine topics are taught.

As well, the school applied the strategies of community-oriented education, with partial implementation of problem-based and student-centered learning concepts.

As it is clear that there is the application of horizontal integration to its maximum end, the vertical integration is carried out in almost all modules. At FMBU, both horizontal and vertical integrations are implemented to the latter. As well FMBU implements a triangular approach in teaching and the assessment places as described by Abdelaziz and Koshak.1 The curriculum and some courses like cardiology and cardiovascular surgery were well received by both the academic staff and the students.2

For developing FMBU curriculum guidelines and strategies, a module committee was tasked with designing, planning, and implementing the EESM. Since it is the first time that such a course was being planned and taught, we followed Harden’s methodology (ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum) for developing the curriculum.3

The work was assigned to two FMBU faculty members in addition to personnel from the Medical Education Development Unit. In this article, a description of how Harden’s questions were answered to design, plan, and implement EESM at FMBU is provided in this paper.

The needs of endocrinology and endocrine surgery module at the FMBU

The main objective of the whole curriculum is to produce doctors who will serve their local community and country, and the world. Many studies (for example Abdullah et al4 and Al Jurayyan5) have revealed that the incidence of endocrine disorders has increased in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in recent decades. After studying the growing incidence of endocrine disorders, Abdullah et al4 recommended the establishment of special health care services for adolescents at the primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels. Al Jurayyan as well stated that the frequency and pattern of endocrine disorders show the need for well-trained pediatricians to improve the health of the population. The need for well-trained doctors in endocrinology and endocrine surgery are clear.5

The newly founded medical school in Al-Baha is community based. The main target of this school is to interact with the community, raise awareness within the community about the dangers of endocrine disorders like diabetes, carry out screening services for apparent endocrine problems like short stature and others, and offer follow-up and refer the needy cases to the health care system.

Our curriculum should respond to the needs of the community by explaining what the product will be able to do by the time he/she has successfully completed the program.

The aims and objectives of EESM

This is a cardinal step in developing the EESM before putting up intended learning outcomes for the module; a module committee was formed and asked to carefully revise the Undergraduate Program Objectives of FMBU. It is an essential step to revise these objectives as the intended learning outcomes of the EESM should match as a part from that whole. Table 1 shows the curriculum aims and the module learning outcomes.

| Table 1 Modules general aims and intended learning outcomes |

Endocrinology and endocrine surgery contents

The module planning committee included the most important contents related to endocrinology and endocrine surgery. The contents were divided into three categories: 1) core knowledge, 2) clinical skills and cases to be seen, and 3) practical skills.

Core knowledge

As shown in Table 2, the most important topics were included. It is sometimes difficult to choose what is suitable for undergraduate study. The extremes are not desirable; therefore, the module committee chose to tread the middle path by excluding both rare and difficult topics that do not suit undergraduate study and important and common topics.

| Table 2 Module contents, instruction methods, and organization Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus. |

In the selection of topics, the committee was guided by the recommended standards in endocrinology and diabetes for undergraduate medical education and suggested strategies prepared by the UK Endocrine Society.6

Clinical skills

The module determined the clinical skills that should be learned by the students. These skills to be learned included common endocrine problems with special interest in diabetes mellitus, thyroid problems, and endocrinology of the reproductive system.

On completion of this module, the students were expected to perform an excellent clinical history and proper physical examination in an endocrine-focused manner. As well, this module would give them the opportunity to follow complex endocrine cases through their treatment and complications. A structured logbook was prepared for this reason.

Practical skills

In addition to the special skills of performing clinical history and physical examination, the procedures that should be practiced and learned by the students during this module (Table 2) are listed.

Endocrinology and endocrine surgery module organization

In response to Harden’s question, how should contents be organized, the distribution of module contents in many categories is shown in Table 2. These include lectures, skill laboratory sessions, hospital-based clinical and practical teaching, problem-based teaching, seminars, and self-directed learning. The distribution of the topics was based on their nature and the committee studied the best way for delivery.

Educational strategies adopted in the EESM

The six major issues described by Harden, the famous SPICES model for curriculum planning is applied. Each issue of these six cover a continuum, the committee chose where to lie in planning this module according to the circumstances, available resources, and directions of the undergraduate medical curriculum at FMBU.

Student-/teacher-centered

EESM is a mainly teacher centered curriculum. Students in the fourth year are not yet mature enough to be involved in all the issues included in the curriculum. However, the committee discussed with the students and involved them in the selection of some contents and assessment methods.3

Problem solving/information gathering

Due to the short time available for the implementation of this module, which was 3 weeks, and the variety of objectives to be covered, the module committee adopted the strategy of problem solving and case-based learning in which the students would be taught and trained to cover multiple problems in a short time. This strategy was chosen with the aim of saving time and raising the clinical skills of students more than information-gathering strategy.

Many studies have concluded that applying problem-solving techniques lead to an increase in the efficiency of learning, develop experienced physicians, and also improve patient care.7

Integrated (multidisciplinary)/specialty (disciplinary)

EESM is delivered through a multidisciplinary approach. The FMBU is adopting a system-based fully integrated curriculum. This integrated strategy was applied in all the modules and despite the difficulties related to human resources and academic staff shortage, this strategy has shown to be successful.2

Community-/hospital-based

Despite the fact that the main activities of EESM are hospital based, community-based activities still take place during the implementation of this module. Two main activities are counted in this respect. First is organizing an open activity with the families of children with diabetes mellitus in which health education messages and handouts are distributed, training is conducted in insulin handling, and dietary control methods are taught by the students, all under the supervision of teaching physicians. Second is organizing visits to homes of such families that have many members suffering from diabetes. These activities are few but they have a strong educational impact when compared to the gained outcome.

Elective/standard

This module planned and implemented the adoption of a standard strategy for choosing and delivering the contents. However, students were given a chance to select topics for self-directed study from a list of uncovered topics. The self-directed topics stated in Table 2 are the most frequently selected topics by the students.3

Systematic (planned)/apprenticeship (opportunistic)

The nature of the curriculum at FMBU and the limited time to learn it led to making the module systematic (planned) rather than apprenticeship. The students were handed the module study guide on the first day so that they could familiarize themselves with all the activities, instruction methods, teaching places, assessment methods, and marks distribution.3

Teaching methods used in EESM

The teaching methods planned by the module planner are listed in Table 2. Lectures and seminars are organized for the whole class in the faculty building. Students are divided into small groups during the skill laboratory sessions, hospital-based clinical teaching, and problem-solving sessions. In individual learning, the students study on their own; this is referred to as self-directed learning. In self-directed learning, the students choose topics of their interest from a structured list and are assessed in this topic by two means. They are asked to prepare a report from the literature and as well will be asked in the written exam. Teaching modalities described by Lisa Vaughn and Raymond Baker are all selected with some modifications to suit our situation.8

At FMBU, there are two approaches for teaching endocrinology topics. The relevant endocrinology topics are taught in relevant system-based and basic medical sciences modules. During the first 3 years, some of the basic concepts related basic medical science like physiology of the endocrine system, hormones biochemistry, and anatomy of the endocrine glands are taught. In basic medical science modules, practical sessions conducted in the laboratory are dominant.

During later clinical years, relevant endocrinology and endocrine surgery topics are taught in the relative body system modules. In these modules, the hospital-based clinical teaching is dominant. Most of the time, availability of teaching place and technology-based learning tools affect the choice of the teaching method.

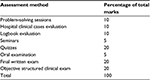

The assessment methods in the EESM

The module planners defined all items of the assessment. These items are clearly described in the module study guide. Table 3 shows the items of assessment and marks distribution.

| Table 3 Assessment methods and marks distribution |

Assessment techniques

Both formative and summative assessment techniques are used. The formative techniques include module portfolio in which the students are asked to record the cases seen, learning points, procedures attended and performed, and the reports of community activities and mid-module quizzes.

The summative assessment includes multiple-choice questions, short essays, and objective structured clinical examination.

Choice of the assessor

The academic staffs who take part in teaching are selected to perform the assessment in addition to the clinicians from the hospitals who also take part in clinical teaching. The external assessors are oriented to the methods of assessment and marking system.

Timing of the assessment

The formative assessment consists of monitoring during the course, while the summative assessment is performed at the end of the module.

Standards

The standard used for the assessment is criterion based, rather than norm based. Criterion-based assessment was chosen because the module planners wanted to make sure that the students achieved the planned specific standards of competency. Those who did not fulfill the criterion stated would not be able to pass.

After implementation, feedback was obtained from the students and the academic staff for evaluation of the module. The results were excellent, in spite of the presence of some weak points. Identifying these weak points would give a chance to improve them during the next implementation.

How the module issues are communicated?

The choice of a module planner and forming the module committee is based on the specialty. There were many levels of communication:

- Planners communicated with departments to include departments output.

- Module committee communicated on technical issues with medical education, academic affairs, and the quality assurance.

- Communication with hospitals and vice-dean for clinical teaching.

- Coordinating meetings with teachers who participated in teaching the module.

- Meeting with students at the start to discuss all issues related to the module and maintaining contact throughout the module with the students’ representative.

The educational environment

Planners were concerned with the implementation environment and worked hard to make it encouraging and productive. Genn described the importance of educational climate and the module committee tried to apply the same in EESM.9

There are many factors that helped to create a productive environment in the EESM such as:

- A variety of activities: the module includes different activities such as classroom teaching, hospital-based teaching, and community-based activities. The aforementioned teaching methods cultivate an enthusiastic attitude in both the students and teachers and makes the curriculum interesting.

- Group distribution helped to create a reactive environment between students themselves and with their tutors alike. This, in turn, proved more supportive and encouraging for both involved.

- Students were very enthusiastic with community-based activities and enjoyed interacting with people at the community level.

Module management

The module committee comprised members from related departments. It included physicians, adult endocrinologists, pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, surgeons, biochemists, physiologists, and anatomists.

The module committee prepared the basic documents including the plan. Then they presented their initial plan to the medical education department which revised and added amendments to the plan and contents. These documents were again revised by the faculty and academic affairs and the clinical teaching coordination committee. Approval was obtained from the quality assurance department before the module plan and documents were finally approved by the faculty board and signed by the dean, faculty of medicine, and became ready for implementation. The hierarchy of the module management is shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Hierarchy of the module management. Abbreviation: EESM, endocrinology and endocrine surgery module. |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Abdelaziz A, Koshak E. Triangular model integrating clinical teaching and assessment. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:61–64. | ||

Elfakey WEM, Koshak EA, Abdelaziz A, Akl U, Alqahtani F, Mady E. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary clinical module on cardiology and cardiovascular surgery at Al-Baha University: students and academic staff perceptions. Educ Med J. 2015;7(3):27–34. | ||

Harden RM. Ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum. Med Educ. 1986;20(4):356–365. | ||

Abdullah MA, Al-Salhi HS, Anani MA, Melendrez LQ. Adolescent endocrinology in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(1):24–30. | ||

Al Jurayyan NAM. Spectrum of endocrine disorders at the Paediatric Endocrine Clinic, King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2012;7(2):99–103. | ||

Society for Endocrinology. Recommended standards in endocrinology and diabetes for undergraduate medical education and suggested strategy for implementation. Available from: http://www.endocrinology.org/clinical/undergraduate/UndergraduateEducation.Full.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2016. | ||

Grosswald SJ. Problem-solving strategies of experienced and novice physicians. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1992;12(4):205–213. | ||

Vaughn L, Baker R. Teaching in the medical setting: balancing teaching styles, learning styles and teaching methods. Med Teach. 2001;23(6):610–612. | ||

Genn JM. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 23 (Part 1): Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—a unifying perspective. Med Teac. 2001;23(4):337–344. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.