Back to Journals » ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research » Volume 15

Teachers’ Willingness to Pay for Social Health Insurance and Its Determinant Factors at Harar Region, Ethiopia, 2021

Authors Girma S, Abebe G, Tamire A , Fekredin H , Taye B

Received 19 November 2022

Accepted for publication 3 March 2023

Published 9 March 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 181—193

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S397766

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Giorgio Colombo

Sintayehu Girma,1 Gizachew Abebe,2 Aklilu Tamire,3 Hamdi Fekredin,3 Bedasa Taye3

1Fred Hollows Foundation, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2Gutazer Health Center, Gurage Zone, South Nation Nationalities and People, Walkite, Ethiopia; 3School of Public Health, College of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Aklilu Tamire, Email [email protected]

Background: Most developing nations lag behind in maintaining their populations’ health. These nations are characterized by under-financing, low health cost protection mechanisms for the poor, and lack of risk pooling and cost sharing methods. To tackle this challenge, Ethiopia proposed social health insurance in 2010 even though its implementation was delayed. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess teachers’ willingness to pay for the newly proposed social health insurance and its associated factors.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted and a stratified sampling technique was used to select government and private schools. After data were collected using a semi-structured self-administered questionnaire, binary and multivariate logistic regressions were done to examine determinants of willingness to pay for social health insurance.

Results: Among participants who faced illness six months prior to the study, 85.7% reported that they paid “out of their pocket”. About 59.2% and 54% of the teachers had a positive attitude and good knowledge toward health insurance schemes respectively. Of the total study respondents, 89.5% were willing to pay for the suggested insurance scheme. Forty eight percent of participants agreed to pay greater than or equal to 4% of their monthly salary. Willingness to pay was more likely among those who taught in secondary schools, had a positive attitude and good knowledge.

Conclusion: Nearly three fourths of the teachers showed willingness to pay for social health insurance. Participants with good knowledge, a positive attitude and from primary schools were more likely to be willing to pay for social health insurance. Equipping all public facilities’ employees with necessary knowledge of social health insurance is essential to reduce catastrophic health care costs. Future researchers need to consider qualitative studies to support these findings.

Keywords: social health insurance, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia, willingness to pay

Introduction

At least half of the world’s population still does not have optimum coverage of essential health services.1 A survey from 89 countries suggested that an estimated 150 million people suffer financial catastrophes due to out-of-pocket payment (OOP) for health service.2 In 2019, the WHO reported that an estimated 930 million people, around 12% of the world’s population, spend at least 10% of their household budgets to pay for health care.1 Catastrophic spending for healthcare is defined as “paying more than 40% of household income directly for health care after basic needs have been met”. Even though it occurs in all countries at all income levels, it is greatest in those that rely most on direct payments to raise funds for health care.2

In most low income countries where government expenditure on health is low, 85% of the cost for healthcare is covered by out-of-pocket payment.3 The removal of user fees aims to reduce financial barriers and health financing through risk pooling mechanisms,4 giving special attention to the poor, promoting universal health coverage and equity.5 The implication of health financing through risk pooling mechanisms is that the healthy will pay for some or all of the health care services and if the mechanism advances, the wealthier will pay for the services used by the poor.6 Health insurance reduces catastrophic health spending, improves access to and use of health care, which ultimately improves health outcomes.7

The Ethiopian health system is characterized by extreme under-financing, low protection mechanisms for the poor, and under financing ways of risk pooling and cost sharing; all of which result in inequality in access to healthcare. Data from trends reported by the World Bank showed that Ethiopia remained one of the highest, 78% from 1995 to 2014 with no improvement between those years. For many households in Ethiopia, a small OOP can result in financial catastrophes.8 A steady drip of medical bills forces people with chronic diseases or disabilities into poverty.9,10 Since the Ethiopian parliament ratified health insurance in 2011, the government has struggled to start compulsory social health insurance and community based health insurance for the formal and informal sectors respectively. The implementation of all forms of health insurance systems in Ethiopia is at the earliest stages of development. In general, health insurance has been nearly non-existent in Ethiopia.11

Recently, the Ethiopian government planned to implement social health insurance (SHI) among employees in the formal sector. This health insurance is meant to provide health insurance for employees of the formal sector and their families. Active employees are expected to pay a monthly premium of 3%, while retired people are required to pay 1% of their monthly salary.12,13

However, little is known about willingness to pay (WTP) for social health insurance (SHI). On the other hand, whether an individual demands SHI and is willing to pay for it depends on the perceived difference between the level of expected utility with insurance and expected utility without insurance.14,15 Despite Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health’s plan to fully implement SHI by 2014,16 it has been repeatedly postponed, largely due to strong resistance from public servants. Hence, this study was conducted to explore public servants’ WTP and factors contributing to resistance to social health insurance. The Ethiopian healthcare system is largely reliant on out-of-pocket spending, exposing many households to financial hardship and causing them to give up seeking healthcare, especially in rural areas of the country. This poor health care financing slows down health improvements in access and utilization of essential health services among the poor and rural communities.17 For example, in 2014/2015 the government and other public enterprises provided 31% of the financing, donors and non-government organizations provided 37%, households provided 31%, and other private employers and funds about 1%.13,18 Educational policy has progressively become an integral part of economic and social policy irrespective of teachers’ economic benefit.19 In Ethiopia, the scarce budget of the government limits the capacity to cover the health care allowance especially for those whose monthly salary is very minimal, including high school teachers.20 The current study focused on employed teachers’ WTP for proposed SHI as teachers in Ethiopia are victims of limited monthly salary, as it does not cover all their expenses in life, including health care.21 Therefore, this study aimed to determine their willingness to pay for SHI so that they can benefit from it, and associated factors among teachers in the Harar region, Eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Study Period

This study was conducted in Harar city Eastern Ethiopia from December to January 2021. Harar is a city located in Eastern Ethiopia, 526 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of the country. Harar city has nine woreda and 19 kebeles, while the rural part of the state has 17 rural kebeles. The state’s size is estimated to be 340 km2. Based on 2019’s population projection from the 2007 Census conducted by the central statistics agency, the Harar National Regional States’ (HNRS) total population was found to be 257,000 and the region has a total of 321 schools with 2693 teachers. According to data from Harar City, there are 27 government and 34 non-government schools with 1065 and 421 teachers, respectively. From these, 46 are primary and 15 are secondary schools, with 1024 and 462 teachers, respectively.

Study Design

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was used.

Sample Size Determination

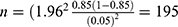

Number of teachers participating in the study was determined by using single population proportion formula with the following assumptions. According to a study done among public servants in Mekelle city in 2017, Northern Ethiopia n=384, 328 (85.3%) were willing to pay for the proposed social health insurance scheme.22

- Proportion of teachers willing to pay for SHI= 85.3% (p=0.85)22

- 95% confidence interval (Z= 1.96)

- Margin of error (d=0.05)

- Sample size was estimated by the formula:

, by adding 10% for potential non-response, the final sample size became 215.

, by adding 10% for potential non-response, the final sample size became 215.

- By considering 1.5 design effect the final sample size became 323 participants.

In this study, stratified sampling method was applied to select primary and secondary government and non-government teachers. The total number of primary and secondary teachers were 1024 and 462 in both government and private schools respectively. By using probability proportional to size for the possible allocation of all teachers. First, primary and secondary government and non- government teachers were divided into 4 strata. Then simple random sampling technique was used to select both government and private schools. Then calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to each stratum. Simple random sampling method was applied to get 323 teachers (Figure 1).

Outcome Variable

Willingness to pay (WTP) for social health insurance.

Independent Variable

Socio-Demographic Factors

Socio-demographic factors incuded age, educational status, family size, professional status, marital status.

Socio-Economic Factors: Monthly Salary and Household Belongings

Health and health-related factors such as the health status of household members, the accessibility of health care facilities, the perceived quality of health care, the presence of chronic disease in household members, medical bills, and so on were included.

Awareness and knowledge of SHI, membership in a social organization, exposure to a source of credit, premium affordability, and the teachers’ trust in system management attitude are all SHI related factors.

Data Collection Procedure

Three data collectors with qualification diplomas were recruited from outside the student health facilities and participated in data collection. The data collection team reached the study area and submitted a supporting letter to Harar city health bureau. After taking support letters from the Harar city health department, data collectors traveled to assigned schools. After permission was obtained from the directors of each school, data collection started immediately by using self-administered structured questionnaires. The questionnaire was developed after extensive revision of different literature. The questionnaire consisted of socio-demographic characteristics, socio-economic factors, health and health-related factors, knowledge of participants, attitudes toward social health insurance, organizational factors and questions related to willingness to pay for social health insurance of teachers.

Data Quality Assurance

One-day training was given to data collectors concerning overall purpose, goal, objectives, content of tools, way of approaching to reduce non-response rate and to increase the data quality of the study. To ensure adherence to data collection protocols and to increase the validity of data collection techniques, supervisors and a research team reviewed the collected data at the end of the data collection day for completeness. The data collection process was supervised closely and daily performance. Any problems encountered during data collection were checked overnight and solutions were planned for the next day. Each morning of data collection day, supervisors and data collectors communicated on how to proceed and solve problems encountered for the next day. Based on the findings from pretest, necessary amendments were made to data collection tools.

Data Analysis and Procedure

Data were entered into Epi data version 4.6.0.6. The entered data were exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Participants who answered more than or equal to mean were scored as having good knowledge of SHI whereas those who answered less than mean were scored as having poor knowledge. Participants’ attitudes had two categories; positive attitudes above certain categories and negative attitudes below that point. This point was calculated by a demarcation threshold formula,[{(total highest score-total lowest score)/2}+total lowest score].23 Descriptive data were analyzed and presented using frequency, percentage, summary measures, charts, and tables. First, bivariate analysis was done to identify candidate variables for multivariate variables. A variable with a p-value of less than 0.25 was taken as a candidate for multivariate analysis. Finally, multivariate analysis was done and variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were taken as significantly associated with WTP.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Haramaya University College of health and medical science. To ensure voluntary participation of each participant, oral informed consent was obtained from each participant. Furthermore, the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed by using a code which is “non-identifier” and also the data were maintained in a safe and protected place.

Result

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

From the 323 study participants, 272 of the teachers completed the form, making a response rate of 84.2%. From these, 186 (68.4%) and 86 (31.6%) were from primary and secondary level schools respectively. One hundred and forty-five (53.3%) of the teachers were male. On the other hand, 61.8% of the study participants had bachelor’s degrees. The median age was 34 (SD ±9.5) years. One hundred and sixty-five (60.3%) were married, followed by 118 unmarried (36%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Teachers in Government and Private Schools of Harar City, Eastern Ethiopia, 2021 (N=272) |

Socio-Economic and Health-Related Factors

The majority of the study participants felt that their health status was very good and 87.1% of the study participants did not have chronic illness. On the other hand, 40.8% of them sought health care from the government health facilities. From the total who experienced illness in the past six months, 63 (23.2%), 85.7% payed out of pocket for treatment (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Health and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Teachers in Government and Private Schools of Harar City, Eastern Ethiopia 2021 (N=272) |

Knowledge and Attitudes of Participants Toward SHI

The majority of the study participants, 209 (76.8%), had heard about schemes. Their sources of information on SHI scheme were television: 186 (89.0%), radio: 130 (62.2%) and the least was conferences: 17 (8.1%) respectively. All of the study participants had no SHI coverage despite the majority (147 (54%)) having good knowledge of SHI (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Teachers’ Knowledge of Social Health Insurance at Harar Government and Private Schools, Eastern Ethiopia January 2021 (N=209) |

Assessment of Teachers’ Attitudes Toward SHI

The majority of the teachers responded that the introduction of SHI should be appreciated. However, 36.8% of teachers responded that they were neutral on budget allocation for health. On the other hand, most of them agreed that SHI can reduce cost burden, promote equity, teachers can benefit from SHI, and they also agreed that teachers can benefit from SHI. Fifty-nine percent of the teachers had a positive attitude (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Attitude of Teachers Toward Social Health Insurance at Government and Private Schools of Harar, Eastern Ethiopia 2021 (N=209) |

Willingness to Pay for Social Health Insurance

One hundred and eighty-nine (69.5%) teachers showed willingness to pay for the proposed social health insurance scheme. Of these, 126 (66.7%) showed willingness to pay 3% while the rest were unwilling to pay 3%. Of those unwilling to pay 3%, 39.7% were willing to pay 2% of their monthly salary. Of those who were willing to pay four percent, 48.8%, 42.6%, 42.6% and 14.7% responded that they would pay a maximum of 4%, 5% and 6% respectively (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Diagrammatic representation of measurement of WTP for SHI among teachers, in Harar city, eastern Ethiopia, 2021(n=272). |

From those unwilling to pay, 83 (30.5%), 9.6% was due to their perception of the quality of service provided followed by lack of confidence in institution (5.10%) and government responsibility (5.10%)(Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Reasons for not being willing to pay for social health insurance among school teachers of Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia 2021 (n=63). |

Predictors of Willingness to Pay for SHI

From total variables entered into multivariate analysis, level of schools, teachers’ knowledge and attitude were significantly associated with WTP for SHI. Teachers from secondary school.

On the other hand, the teachers who had good knowledge were 2.785 times more likely to pay for social health insurance as compared to those with poor knowledge (AOR= 2.785,95% CI =1.509 to 5.142). The teachers who had bad attitudes were 0.284 times less likely to pay for SHI (AOR 0.284,95% CI= 0.156 to 0.517) (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Determinants of Willingness to Pay for Social Health Insurance at Government and Private Schools of Harar Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2021 (N=209) |

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the willingness to pay for social health insurance and associated factors among teachers in Eastern Ethiopia. The study revealed that nearly three fourths of the respondents are willing to pay for SHI, which is lower than a study reported in Mekelle City, Ethiopia.22 The difference is possibly due to the difference in response rate. In the current study, the response rate was 84% while in Mekelle City the rate was about 99.2%.22

In the current study, more than three fourths of teachers had heard of the health insurance scheme, which is higher as compared to studies done in other parts of Ethiopia.24 On the other hand, respondents in this study had better knowledge regarding SHI as compared to a qualitative study conducted in Addis Ababa where little knowledge of participants was reported.20 This may lead to high participation in SHI, which in turn contributes to a reduction in catastrophic costs for health care. However, the participants in this study had no previous exposure to the insurance scheme and perceived benefit from it, while nearly half of the study participants in Nigeria demanded to be enrolled in the insurance scheme.25

Among those who showed willingness to pay 3%, nearly half of them were ready to contribute greater than or equal to 4% of their monthly salary as a monthly premium. This is greater than the study done in Northwest Ethiopia where nearly three percent of the study participants showed willingness to pay.25 The inconsistency may be due to the difference in awareness and attitude of study participants between the study settings. It was found that nearly eight in ten of the respondents used out-of-pocket financing to cover their medical bills. This is in line with similar studies conducted in southern Ethiopia.24 The possible explanation for this may be due to the fact that the Ethiopian health financing system has been based on out of pocket payment throughout the country. However, the magnitude of those paying “out of their pocket” was higher than in studies done in Nigeria.25 The possible explanation might be that employees from the public sector of Ethiopia are not used to any insurance for their health care. Consequently, they are used to an expensive out-of-pocket payment system to cover their health bills.

Respondents from primary level schools were more likely to be willing to pay than those from secondary level, which is more comparable with the findings from China.26 This might be due to the fact that people from secondary schools may have relatively higher confidence in covering the cost of health from their pockets than those at primary school level. Participants with good knowledge were more willing to pay for SHI than the others. On the other hand, teachers with positive attitudes were more likely to be willing to pay than those with different attitudes. However, single (unmarried) participants were less likely to pay for SHI.

The Implication of the Findings

In this study, the majority of the teachers were willing to pay for proposed SHI. It is very important to enroll teachers and similar civil servants from sectors with very low monthly salary to SHI so that they will not be the victim of the disproportionate rising costs of health care expenditure. On the other hand, efficient enrollment in SHI adds value greater than its costs. SHI adds costs to the health care system of a country as it is an extra factor in the health care system.27 If implemented well in Ethiopia, SHI can mobilize revenue for health care, reform health sector performance, provide universal coverage and it can also balance the health care coverage among the poor and rich individuals.28 Furthermore, teachers’ good knowledge and positive attitude toward SHI increase the enrollment of the teacher population so that they may not suffer from financial catastrophes due to non-proportionate increment of out-of-pocket payment for health care and teachers’ monthly salary.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that nearly three fourths of the teachers showed willingness to pay for social health insurance. More than eight in ten of the participants had paid for health care from their pocket. Being in line with their willingness to pay, more than half and nearly six in ten of the study participants had good knowledge and positive attitude toward social health insurance respectively. Participants with good knowledge, positive attitude and from primary schools showed more willingness to pay for social health insurance. However unmarried participants were less likely to pay for it. Equipping all public facilities’ employees with necessary knowledge of social health insurance is essential to reduce catastrophic health care costs . Future researchers need to consider a qualitative study to support these findings.

Abbreviations

OOP, out of pocket; SHI, Social Health Insurance; WTP, Willingness to Pay.

Data Sharing Statement

The supporting data of this study are available on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted according to Haramaya university research protocol which is in line with the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki declaration. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of health and medical science, Haramaya University. To ensure voluntary participation of each participant, oral informed consent, approved by IRB, was obtained from each participant. This is because the study involved only the interviews and no other invasive procedures. All study participants were informed that participation was voluntary and also they could discontinue the study whenever they wanted. Furthermore, the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed by using codes which were “non-identifiers” instead of names of study participants.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Haramaya university department of health policy and management for technical support. Furthermore, our gratitude goes to Harar city educational bureau for their cooperation during this work. Lastly, we would like to thank the participants, supervisors and data collectors for their contribution to this work.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; have drafted or written, or substantially revised or critically reviewed the article; have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted; reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission, during revision and any significant changes introduced at the proofing stage; agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Vian TJG. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(sup1):1694744. doi:10.1080/16549716.2019.1694744

2. Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, et al. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff. 2007;26(4):972–983. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972

3. Gollogly L. World Health Statistics 2009. World Health Organization; 2009.

4. Ir P, Bigdeli MJTL. Removal of user fees and universal health-care coverage. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):608. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61515-4

5. Frenk JJTL. Leading the way towards universal health coverage: a call to action. Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1352–1358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61467-7

6. Pettigrew LM. Mathauer, voluntary health insurance expenditure in low-and middle-income countries: exploring trends during 1995–2012 and policy implications for progress towards universal health coverage. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–19.

7. Bocchini CE. Commentary on trends in child health insurance coverage: a local perspective. J Appl Res Child. 2013;4(2):11.

8. Savedoff WD. Kenneth Arrow and the birth of health economics. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:139–140.

9. Etienne C, Asamoa-Baah A, Evans DB. Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. World Health Organization; 2010.

10. Yip WC, Hsiao WC. Non-evidence-based policy: how effective is China’s new cooperative medical scheme in reducing medical impoverishment? In: Health Care Policy in East Asia: A World Scientific Reference: Volume 1: Health Care System Reform and Policy Research in China. World Scientific; 2020:85–105.

11. Mariam DH. Exploring alternatives for financing health care in Ethiopia: an introductory review article. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2001;15(3):153–163.

12. Tegegne AA, Braka F, Shebeshi ME, et al. Characteristics of wild polio virus outbreak investigation and response in Ethiopia in 2013–2014: implications for prevention of outbreaks due to importations. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1–10.

13. Rispel LJ. Analysing the progress and fault lines of health sector transformation in South Africa. S Afr Health Rev. 2016;2016(1):17–23.

14. Kirigia JM, Sambo LG, Nganda B, et al. Determinants of health insurance ownership among South African women. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):1–10.

15. Reshmi B, Nair NS, Sabu KM, et al. Awareness of health insurance in a south Indian population: a community based study. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2007;30(3):177–188.

16. Haile M, Ololo S, Megersa BJ. Willingness to join community-based health insurance among rural households of debub bench district, bench maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10.

17. Mebratie A, Sparrow R, Yilma Z, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Essays on evaluating a community based health insurance scheme in rural Ethiopia. Health Policy and Planning. 2015;30:1296–1306. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu142

18. Mesafint ZJ. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Addia Ababa. 2007;5(6):

19. Buchberger F, Campos BP, Kallos D, Stephenson J. Green paper on teacher education; high quality teacher education for high quality education and training; 2000.

20. Obse AD. Normand, knowledge of and preferences for health insurance among formal sector employees in Addis Ababa: a qualitative study. Annu Rev Pathol. 2015;15(1):1–11.

21. Goshu BS. Woldeamanuel, Society, and B. Science, Education quality challenges in Ethiopian secondary schools. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;31(2):1–15.

22. Gidey MT, Gebretekle GB, Hogan ME, Fenta TG. Willingness to pay for social health insurance and its determinants among public servants in Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia: a mixed methods study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2019;17(1):1–11.

23. Kitila SB. Yadassa, Client satisfaction with abortion service and associated factors among clients visiting health facilities in Jimma town, Jimma, south west, Ethiopia. Qual Prim Care. 2016;24(2):67–76.

24. Agago TA, Woldie M. Willingness to join and pay for the newly proposed social health insurance among teachers in Wolaita Sodo town, South Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24(3):195–202.

25. Uzochukwu B, Ughasoro MD, Etiaba E, et al. Health care financing in Nigeria: implications for achieving universal health coverage. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18(4):437–444. doi:10.4103/1119-3077.154196

26. Bärnighausen T, Liu Y, Zhang X, et al. Willingness to pay for social health insurance among informal sector workers in Wuhan, China: a contingent valuation study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):1–16.

27. Bank, W. Social health insurance_FINAL_English_spreads_0; 2017.

28. Shaw RP. Social Health Insurance for Developing Nations. World Bank Publications; 2007.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.