Back to Archived Journals » Medicolegal and Bioethics » Volume 9

Surgical And Medical Error Claims In Ethiopia: Trends Observed From 125 Decisions Made By The Federal Ethics Committee For Health Professionals Ethics Review

Authors Wamisho BL , Tiruneh MA , Enkubahiry Teklemariam L

Received 17 June 2019

Accepted for publication 7 October 2019

Published 23 October 2019 Volume 2019:9 Pages 23—31

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/MB.S219778

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Bethany Spielman

Biruk L Wamisho,1 Mesafint Abeje Tiruneh,2 Lidiya Enkubahiry Teklemariam2

1Head, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Addis Ababa University (AAU), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2Ethiopian Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Biruk L Wamisho

Head, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Addis Ababa University (AAU), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Email [email protected]

Background: Surgical and medical errors are not uncommon but the majority are often subtle. Even in highly developed countries, medical error is the third highest leading cause of death. Patient harm from medical error can occur at an individual or a system level.

Methods and materials: A decision data base of the Health Professionals Ethics Committee that reviews medical error complaints and malpractice claims available at Federal level was used. Descriptive statistics were used to describe and see trends observed over seven years, 2011–2017, inclusive. Numbers from National data were used to see the 10-year trend.

Results: In the seven-year review period, the committee made a final decision on 125 complaints. Over 20 types of health professions were present. Death was the issue in 72 (57.6%) of them and 27 (21.6%) of the claimants associated the error with bodily injury. The majority of complaints, 94 (75.2%), were from hospitals. Most of the complaints were surgical-related and emerged from the operation room (90/125, 72%). Forty-one (28.1%) complaints were against obstetricians and gynecologists, 15 (10.2%) against general surgeons, and eight (5.5%) against orthopedic surgeons. Among all complaints, in 27 (21.6%) claims, actual ethical breach or medical error was found. Gross professional negligence was observed in four of these and the professionals were permanently prevented from practicing medicine at all.

Conclusion: In Ethiopia, an increasing number of applications is filed for investigation of possible surgical/medical error. Most of the complaints did not result in payouts; only one fifth benefited the plaintiff. Some specialties are particularly at high risk for accusations.

Recommendations: The increasing number of complaints filed for medical error investigation in Ethiopia needs deeper investigation by all stakeholders. Routine patient safety measures have to be exercised to prevent/decrease incidents of surgical/medical errors.

Keywords: surgical and medical errors, ethics committee, health professionals, Ethiopia

Introduction

A medical error is commonly defined as an unintended act (either of omission or commission) or one that does not achieve its intended outcome, the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (an error of execution), the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (an error of planning), or a deviation from the process of care that may or may not cause harm to the patient.1 Patient harm from medical error can occur at the individual or system level. The taxonomy of errors is so many and is always expanding to better categorize preventable factors and events. Preventable adverse event (PAE) is a better terminology proposed these days.2

This definition of medical error includes explicitly the key domains of error causation (omission and commission, planning and execution), and captures faulty processes that can and do lead to errors, whether adverse outcomes occur or not. The inclusivity and explicitness of the definition should make it useful for research into the etiology of errors from the perspective of the provider: given this definition, a health care worker has a clear roadmap with which to designate a process as error-prone or error-laden. By including potential adverse outcomes, the definition includes the “silent majority” of errors that do not cause harm but reflect faulty processes. At the same time, it ignores trivial mistakes (for example, taking the wrong route to visit a patient) that have no potential for adverse outcome.3

Medical error is a common encounter and represents an important public health problem posing a serious threat to patient safety. A study released in 2016 found medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease and cancer. Researchers looked at studies that analyzed the medical death rate data from 2000 to 2008 and extrapolated that over 250,000 deaths per year had stemmed from a medical error, which translates to 9.5% of all deaths annually in the United States of America.3

Ethics can be referred to as a study of the standards of conduct and moral judgment as well the code of morals of a particular profession. Ethics are always presented in the form of values, theories, and principles. Ethical values, theories, and principles can influence health professionals’ ethical decision making. Ethics include not only what ought to be done but also what must be done in a compassionate, respectful, and caring manner.4

Not properly practicing medical ethics, poor management and solution for medical error not only threaten to weaken patient-health professional relationship, but may also lead to poor quality health service delivery and high incidences of violence and abuse.5,6

Health professionals encounter ethical issues every day. These ethical issues involve doing what is right, fair, honest, and legal. It is concerned with arriving at the best course of action in health facilities presenting ethical dilemmas so that the best interests of the patients and clients will be maintained. Health professionals might face situations where there are conflicts between values and uncertainty about what course of action to take. Sometimes, there are equally compelling reasons for or against possible courses of action.7

Ethical dilemmas in the health care setting are common. Some of the ethical issues health professionals encounter include those issues related to end-of-life care, resuscitation, consent, competence, care and treatment decisions, and overall organizational healthcare management. Ethics in health services have been seen as an integrated part of health care workers’ profession, and primarily something that health professionals themselves handle as part of their daily work in health facilities.7

Medical errors are a very common phenomenon in health care settings worldwide which can cause temporary or permanent harm or death. The other consequence of medical error is high economic burden on the health care system.8

Medical malpractice claims may arise when health professionals, through an error or omission in diagnosis, treatment, aftercare or health management, cause an injury and/or death in a patient. The definition of error or omission is based upon the deviation of the health professional from a generally accepted standard of care. However, an injury or inadvertent complication that is the result of a medical treatment is not malpractice if the health professional administering the treatment properly advised the patient about the potential risks, obtained consent, and exercised appropriate/standard care in providing the treatment.9

Health services have become more specialized and complex.

Nowadays, health professionals seem to work under pressure from fear of committing possible error and get sued.7 Effective response to ethical concerns is essential for both individuals and health facilities. When ethical concerns are not resolved properly, the result can be errors or unnecessary and potentially costly decisions that can be bad for patients/clients, health professionals, health facilities, and society at large.10–12 In addition, failure to maintain an effective medical ethics regulation program can seriously jeopardize health facilities' reputation and harm the health profession.13

Health professionals’ ethics are also closely related to quality of health care. A health professional who fails to meet established ethical norms and standards (code of ethics) could not deliver quality health care. Similarly, failure to meet the minimum quality standards raises ethical concerns. Hence ethics and quality of health care could not be seen separately.14

Simply responding to each ethics question as they arise is not enough to resolve the problem. It is also important to address the underlying systems and processes that influence health professionals’ behavior. Implementation of ethical norms and principles needs a systematic approach to proactively identify, prioritize, and address concerns about professional ethics at the health facility level.14

According to Proclamation No. 661/2009 Ethiopian Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority (EFMHACA) and regional health regulatory bodies have the mandate to regulate health professionals including assurance of competency and ethics.15

The first Federal Health Professionals Ethics Committee was established in 2002 under Ethiopian Health Professionals Council. It was functional until 2013.16 To ensure health professionals' ethics in health facilities, health professionals’ Code of Ethics was developed and endorsed through Regulation No. 299/2013. Based on this Regulation, Federal Health Professionals Ethics Committee was reorganized. According to the powers and duties given: the committee shall examine, investigate, and propose appropriate administrative measures the Authority on complaints made with respect to substandard health service and incompetent and unethical health professionals; shall, where it proves available sufficient evidence to support the complaint, send summons to the health professional or institution against whom a complaint is lodged with the notification to respond within 30 days; may, where appropriate, assign an independent researcher in consultation with the Authority to investigate the complaint; may propose suspension of license or certificate of competence to the Authority until the appropriate decision is passed on the complaint; shall, upon identifying the root cause of frequently lodged complaints and grievances, propose policy directions intended to provide sustainable solutions to the problems; shall perform such other duties that may be assigned to it by the Authority. Ethiopia is currently establishing a new proclamation to replace the old one.17

Since there is limited information in the country regarding health professionals’ ethics and surgical and medical error trends, this review will provide information for concerned stakeholders to design strategies for the implementation of a code of ethics.

Therefore, the objective of this article was to review surgical and medical error investigation files submitted to the federal ethics committee and summarize the decisions/administrative measures taken in the last seven years.

Materials And Methods

The database prepared to prospectively feed in the decisions passed by the Federal Health Professionals Ethics committee was organized. Variables on the datasheet were prospectively filled every time when a decision was made. Analysis of the seven years' (January, 2011 to December 2017) decisions was done in September 2018. Only numbers of claims reviewed by other similar committees in the regions were included to observe ten-year trend at national level; otherwise these data are Federal.

The Committee collected information from concerned bodies for each case and requested additional professional opinions from professional associations and universities. The committee also reviewed complaints thoroughly to reach the final decision. The report includes all complaints coming from various bodies such as police, court, patient/client, patient families, and other governmental organizations including Federal Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa Health Bureau and Addis Ababa Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority. In addition, the report contains case handling process, decisions made by the committee, and administrative measures taken by EFMHACA.

The data were collected using a checklist which was prepared by the investigators. Variables collected for each case included: who filed the complaint, cause of complaints, outcome of the incidents, type of health facility the incident happened in, specialties and health professionals involved in the complaint, decisions suggested by the ethics committee, type of health facilities and administrative measures taken. Descriptive data analysis was done and results are presented in relevant descriptive statistics.

The investigators got permission from Ethiopian Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority (EFMHACA) to conduct this review and to publish the findings.

Results

General Information

The Federal Health Professionals’ Ethics Committee is composed of 19 Senior Health Professional members from Professional Societies/Associations, Federal Ministry of Health, regulatory authorities, and lawyers too. The specialists investigating the claims have over ten-year experience in their specialties. In seven years (2011–2017), 125 incidents were investigated and case files closed. Only 22 cases at federal level are pending. One hundred and forty-six professionals from over 20 different types of health professions were involved.

Who Filed The Complaints?

Among the complaints, 47 (37.6%) were filed by patients/family of patients followed by police/regular courts, 42 (33.6%). 12 health professionals had already been arrested by the police and put in prison before the committee reviewed the incident and forwarded a decision. Media report declaring that there was a “medical error” was aired or released to the public before any investigation or decision in 15 cases (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Complaints Submitted To The Federal Health Professionals Ethics Committee Of Ethiopia, January 2011-December 2017 (n=125) |

Causes Of Complaints And The Final Outcome Of The Health Service Provided

Death was the reason to file for investigation in 72 (57.6%) of the claims and bodily injury was the reason in 27 (21.6%) of the complaints (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Surgical And Medical Error Claims Reviewed In Ethiopia, Final Outcome Of The Incident, January 2011-December 2017 (n=125) |

Type Of Health Facility The Incident Happened In

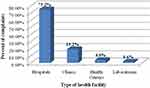

From all complaints, 60 (48%) of them happened in governmental health facilities and 65 (52%) of them in private health facilities. From those complaints, the majority, 94 (75.2%), were from hospitals followed by clinics, 24 (19.2%) (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Surgical and medical error claims reviewed in Ethiopia: type of health facility where the incident happened, January 2011-December 2017 (n=125). |

Specialties And List Of Health Professionals Involved In The Complaint

In the last 10 years increasing trend observed in number of medical error claims in Ethiopia (Figure 2). Most of the complaints were surgical and emerged from the Operating Rooms (90/125, 72%). In some complaints more than one health professional was involved. Specialists considered, 41 (28.1%) of complaints were against Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 15 (10.2%) against General Surgeons, and 8 (5.5%) were against Orthopedic Surgeons. 20 (13.7%) nurses were investigated (Table 3).

|

Figure 2 A 10-year increasing trend observed in number of medical error claims in Ethiopia. (Some Regions in Ethiopia established the Committees recently). |

|

Table 3 Surgical And Medical Error Claims Reviewed In Ethiopia, Categories Of Health Profession And Professionals Involved; January 2011-December 2017 (n=146) |

Complaints And Professional Opinions

Even though the Federal Health Professionals Ethics Committee is a mix of various professionals, it further requested professional opinions from universities and health professional Associations and Societies that could assist the committee in the investigation and decision making process. The committee requested additional professional opinions from health professional associations in 31 (25%) cases and from major University departments in 6 (4.8%) cases. Such cases were multidisciplinary and very complex in nature.

Decisions Suggested By The Ethics Committee

Among all complaints, in 27 (21.6%) claims actual ethical breach or medical error was found. The major issues identified were lack of competence, practicing beyond professional scope of practice, practicing beyond the standard of the health facility, inappropriate sexual advance and physical examination, and poor recording/documenting of patient information. Gross negligence was established in six of the investigations. These included wrong site surgeries, miss or delayed diagnoses, unnecessary infection, wrong medicines, wrong implants leading to serious consequences. Files involving sexual assault were criminalized and were immediately transferred to criminal courts.

Five (4%) of the files were closed without any decision. This in itself is taken as a decision. Three files were transferred to other similar committees (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Surgical And Medical Error Claims Reviewed In Ethiopia: Decisions Of The Investigating Federal Ethics Committee, January 2011-December 2017 (n=125) |

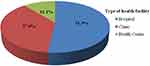

Among the 27 complaints in which actual ethical breach or medical error was found, 16 (59.3%) were from private health facilities where as 11 (40.7%) were from governmental health facilities. From these cases, 14 (51.9%) took place in hospitals followed by clinics, 10 (37%) (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Surgical and medical error claims reviewed in Ethiopia: type of facility where error or ethical breach actually happened, January 2011-December 2017 (n=27). |

In addition to complaints in which actual medical error or ethical breach was found, administrative issues were entertained in18 cases such as practicing without a valid and renewed professional license, issues related to settlement of payment and detainment of deceased’s body.

The committee took a minimum of two weeks and a maximum of three years to finalize investigation and propose the final decision on the previously mentioned cases. The average time taken to complete the investigation and reach a final decision was 9.6 months.

Administrative Measures Taken By EFMHACA

Administrative measures were taken by EFMHACA according to Proclamation No. 661/2009 and Regulation No. 299/2013 against those who were guilty of ethical breach and/medical error. Surgical/medical error was found in 27 (21.6%) of the claims. Among 146 health professionals against whom complaints were raised, 39 (26.7%) breached medical ethics or committed medical error. Administrative measures were taken by the regulatory (EFMHACA). Decision to suspend from practice was passed on 18.4% (27/146) of the health professionals. Over 82% of the administrative measures were mild. Due to serious/gross ethical breaches, four (10.3%, n=39) of health professionals’ licenses were permanently revoked and 23 (58.9%, n=39) suspended temporarily (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Surgical And Medical Error Claims Reviewed In Ethiopia: Administrative Measures Taken By EFMHACA, January 2011-December 2017 (n=39) |

Discussion

Medical malpractice occurs when a medical professional, hospital or any other entity directly injures a patient through a negligent act or an omission (the failure to act). Most mistakes performed by medical practitioners on patients can be considered medical errors, but may not rise to a level of medical malpractice. Although most people tend to use the words interchangeably, they are not synonymous. Medical errors cannot be remedied by law without the elements of harm, negligence, and the deviation from minimal expected standards of care. Medical errors could be precursors to malpractice occurrences. Errors could be at prevention, diagnosis, treatment, following up or at any other system level.18

Health care facilities and practitioners have recently decided to place an emphasis on correcting medical errors before they progress and turn into mistakes that could constitute malpractice, in hope of avoiding future lawsuits. But with the rising rates of malpractice claims pursued by patients, it is evident that much more work needs to be done on behalf of physicians, administrators, lawmakers, and advocacy groups to improve rapidly growing medical error and malpractice complaints – an epidemic that every country is currently facing.18

Doctors and patients are not generally seen as adversaries and great trust links the two. But with commercialization, this relationship has not retained the age old sanctity, which is a matter of great concern to the medical profession. The changing doctor-patient relationship and commercialization of modern medical practice have affected the practice of medicine. These days, it is customary to see a patient as plaintiff and a health professional as a defendant in several civil lawsuits. In countries like Ethiopia, institutions or insurance are not involved. On the one hand, there can be unfavorable results of treatment and on the other hand the patient suspects “negligence” as a cause of their suffering. There is an increasing trend of medical litigation by unsatisfied patients.19

The Medico-legal issue is a common cross-road where medicine meets humanity. It is handled by senior faculty both from medicine and law. It needs careful and complex analysis. Usually, arguments involving medico-legal matters are reviewed by a senior specialist who has been in practice for at least 10 years.20

The Health Professionals Ethics Federal Committee of Ethiopia operates in its scope and mandate emerging from the following pertinent declarations: The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Constitution, Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Proclamation No. 661/2009, Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Regulation No. 299/2013, EFMHACA establishment Regulation No. 189/2009, The 2004 FDRE Criminal Code, Proclamation No. 414/2004 and The 1960 Civil Code of Ethiopia. It follows legal procedures, receives complaints, investigates and gives independent expert opinion. There is procedural TOR and also a clear algorithm for appeal. Regional states have their own similar versions.

The Federal Ethics Committee is composed of senior members from all mainstream health professions, who have been in practice for over ten years as well as lawyers. We feel that credible and balanced decisions are passed with such composition of senior professionals, public representatives, and lawyers.20

As shown on Table 1, anyone can file for an investigation; hence most of the files are opened by the patient or a family member. Usually patients/relatives sue after getting opinions from the committee. If the ethics committee investigation does not show medical error, clients/patients may not go to court. Courts/Police requested the committee’s opinion in 33.6% of the cases. Either the plaintiff or the defendant can request for investigation and expert opinion from ethics committees. We witnessed increasing requests for professional/expert opinion from courts, before passing their final decision.21

Death is involved in more than half of the complaints (57.6%). In around 80% of the files, there is death or physical disability, as final outcome. This is consistent with other reports.22 Operation room is the main place where disputes occur. This is shown by the fact that three quarters of the claimants had surgical care. Disciplines using the operation room are at a higher risk of being sued. This is in line with general literature.23

As most of the incidents involved a form of surgical care provider, it is obvious that hospitals would be sued the most compared toclinics or centers. Gross negligence resulting in total revocation of license to practice was seen in four incidents. Only one fifth (21.6%) of the claims were proven to have some form of surgical/medical error.

Potential media bias was frequently encountered by the committee. Appellate hearing reversed only two of the decisions. This is a consistent figure with international data.24 In the last ten years (2009–2018), an increasing trend of applications for investigation of surgical/medical error has been observed in Ethiopia. This is seen as a trend equation: Y=5.4x-6 with R-Squared (coefficient of determination) value of 0.95 (95%). F-test of 30.7 shows this increase is statistically significant. But still, it is a fact that most medical errors are not reported and claims are only made in less than 3%, even in developed countries.25 On average, it took over 9 months for the committee to give its expert opinion. This is relatively quicker than most such investigations handled by the courts in Ethiopia.

In “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System”, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) demonstrates that technological advances in the hospital setting do not come without consequences. In this report, the IOM revealed that of the 98,000 hospital deaths that can be attributed to medical errors each year, 90% are the result of failed systems and procedures.26,27 The IOM report also emphasizes that the cause of most of preventable adverse events is neither negligence nor carelessness but, rather, the result of the inevitability of human errors. The theme is not that we must “do better” as individuals but rather that we must acknowledge our individual fallibility and implement systemic approaches to reducing and intercepting errors. As Leape puts it, “errors result from faulty systems not from faulty people!”.28 The issue of patient safety plays a prominent role in health care. Its prominence is fueled by an expanding body of literature that shows a high incidence of error in medicine, coupled with well-publicized medical error cases by the media that have raised public concern about the safety of modern health care delivery.29 There has to be a check and balance mechanism that maintains the doctor-patient trust while addressing medico legal issues, media, and public safety. Patients shall feel safe and professionals shall not be frustrated. Medical error claim investigation can be well addressed by such Medico-Legal Committees (MLC) and surgical disciplines are most affected, needing serious attention.23

Conclusion And Recommendations

Medical error and malpractice investigation requests are alarmingly increasing in Ethiopia. But, medical errors are not just the result of human error, but also the result of the systems in which humans work and interact. Thus, any improvement in reducing medical errors must come from looking at the systems and processes as a whole, not just at the individual level.

The growing awareness of the frequency, causes and consequences of error in medicine reinforces an imperative to improve our understanding of the problem and to devise workable solutions and prevention strategies. Variations in nomenclature without a universally accepted definition of medical error hinder data collection and collaborative work to improve health care systems. If health care providers and researchers are to improve patient safety, we must all speak the same language.

For hospitals and other institutions, the introduction of technical change, although necessary and desirable, carries with it a responsibility to guard against potential risks. Institutions are obligated to investigate adverse events as they transpire, and work to prevent recurrences. To preserve patient safety, hospitals must focus on overall quality improvement, not individual blame and punishment. Some institutions have overcome the challenges involved in meeting this goal, and implemented creative plans that increase communication about and learning from medical errors.

To reduce the incidence of errors, health care providers must identify their causes, devise solutions, and measure the success of improvement efforts. Moreover, accurate measurements of the incidence of error, based on clear and consistent definitions, are essential prerequisites for effective action. The common initial reaction is to find and blame someone when an error occurs. However, even apparently single events or errors are due most often to the convergence of multiple contributing factors. Blaming an individual does not change these factors and the same error is likely to recur. Preventing errors and improving safety for patients require a systems approach in order to modify the conditions that contribute to errors. People working in health care are among the most educated and dedicated workforce in any industry. The problem is not bad professionals, the problem is that the system needs to be made safer. Potential media bias and health professionals' inappropriate arrest procedures have to be addressed by the regulatory/government not to prejudice the public as well as the committee.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Grober, ED, Bohnen, JA. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39–44.

2. Kohn KT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

3. Martin A, Michael D. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:2139.

4. Health PEI Clinical Ethics Committee Clinical and Organizational Ethical Decision–Making Guidelines. June 2012.

5. Baldwin D

6. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Christakis NA. Do clinical clerks suffer ethical erosion? Students’ perceptions of their ethical environment and personal development. Acad Med. 1994;69(8):670–679. doi:10.1097/00001888-199408000-00017

7. Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo. Manual for Working in a Clinical Ethics Committee in Secondary Health Services. July 2012.

8. Vozikis A, Riga M. Patterns of Medical Errors: A Challenge for Quality Assurance in the Greek Health System, Quality Assurance and Management. University of Piraeus. 2012:245–266.

9. Hannover re. Medical malpractice. February 2017. Available from: www.hannover-re.com.

10. Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1166–1172. doi:10.1001/jama.290.9.1166

11. Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD. Impact of ethics consultations in the intensive care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3920–3924. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00033

12. Heilicser BJ, Meltzer D, Siegler M. The effect of clinical medical ethics consultation on healthcare costs. J Clin Ethics. 2000;11(1):31–38.

13. Gellerman S. Why Good Managers Make Bad Ethical Choices. Harvard Business Review on Corporate Ethics. Cambridge, MA: HBS Press; 2003.

14. Ellen F, Kenneth A, Barbara L, Tia P. Integrated Ethics: Improving ethics quality in health care. In: National Center for Ethics in Health Care, editor. Washington, DC; Viterans Health Administration. 2005:7.

15. Federal Demcratic Republic of Ethiopian, The House of Peoples Representatives. Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administratuion and Control Proclamation No. 661/2009. Fed Negarit Gazeta. 2010;9(13):5180.

16. Federal Democratice Republic of Ethiopia, The House of Peoples Representatives. Ethiopian Health Profesionals Council Establishment Council of Ministers Regulation No. 76/2002. Fed Negarit Gazeta. 2002;13:1686–1693.

17. Federal Democratice Republic of Ethiopia, The House of Peoples Representatives. Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administratuion and Control Council of Ministers Regulation No. 299/2013. Fed Negarit Gazeta. 2014;11(24):7210.

18. Letitia P. Investigating the reasons behind the increase in medical negligence claims. PER/PELJ. 2016;19(1).

19. Pandit M, Shobha P. Medical negligence: criminal prosecution of medical professionals, importance of medical evidence: some guidelines for medical practitioners. Indian J Urol. 2009;25(3):379–383. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.56207

20. James D. The medico-legal expertise: solid medicine, sufficient legal and a measure of common sense. Mcgill J Med. 2006;9(2):147–151.

21. Zhan W. Medical malpractice litigation in China. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(6):430–436. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.179143

22. Peters P. Tenty years of evidence on the outcomes of malpractice claims. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:352–357. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0631-7

23. Jamal S, Al Jarallah NA. The pattern of medical errors and litigation against doctors in Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2013;20(2):98–105. doi:10.4103/2230-8229.114771

24. Dwight G. Dropped medical malpractice claims: their surprising frequency, apparent causes, and potential remedies. Health Aff. 2011;30(7):1343–1350. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1132

25. Joseph B. Malpractice: problems and solutions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:715–720. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2782-9

26. Maria A, Courtney D, Storm J, Howard A. Medical errors: physician and institutional responsibilities. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(1):24.

27. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Waschington, DC; National Academies Press. 2000.

28. Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients: results of the harvard medical practice study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:377–384. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240605

29. Cook R, Woods D, Miller C. A Tale of Two Stories: Contrasting Views of Patient Safety. Chicago: National Patient Safety Foundation; 1998.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.