Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 15

Suicide Attempts Among Adult Eritrean Refugees in Tigray, Ethiopia: Prevalence and Associated Factors

Authors Gebremeskel TG , Berhe M, Tesfa Berhe E

Received 16 March 2021

Accepted for publication 15 November 2021

Published 2 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 133—140

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S311335

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Kent Rondeau

Teferi Gebru Gebremeskel,1,2 Mulaw Berhe,3 Elsa Tesfa Berhe1,4

1Department of Reproductive Health, College of Health Sciences, Aksum University, Aksum, Ethiopia; 2Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia; 3Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Aksum University, Aksum, Ethiopia; 4Sexual Reproductive Health Department, Medicine Sans Frontier MSFUM Rakuba Project in Gedarif State, Gedarif, Sudan

Correspondence: Teferi Gebru Gebremeskel Email [email protected]

Purpose: The present study assessed the prevalence of and factors associated with suicide attempts among adult Eritrean refugees in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out among adult refugees from February 2020 to April 2020. The exposure variables included socio-demographic, clinically related, and psychosocial characteristics, and substance use-related factors. We included 400 participants and recruited them via a systematic random sampling technique. The study participants were between 18 and 60 years old. Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. We applied bivariable and multivariable logistic regression to determine predictors for suicide attempts. Multicollinearity was checked to test correlations among predictor variables, and the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p> 0.2) was conducted to check the fitness of the model. Odds ratios and p-values were determined to check the associations between variables, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered as a cut-off for statistical significance.

Results: The prevalence of suicide attempts was 7.3% (95% CI: 4.8%, 9.8%). Having current symptoms of trauma (AOR=5.6, 95% CI: 2.1, 14.9), a family history of mental disorder (AOR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.01, 9.07), a history of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (AOR=2.7, 95% CI: 1.01, 7.4), and severe hopelessness (AOR=3.9, 95% CI: 1.3, 12.7) were significantly associated with suicide attempts.

Conclusion: This study showed that during the stay in the refugee camp, there was a high prevalence of suicide attempts compared to the prevalence of suicide attempts among the general populations of Ethiopia, Europe, and China, and the lifetime pooled prevalence across 17 countries. Current symptoms of trauma, PTSD, a family history of mental illness, and hopelessness were the factors statistically associated with the suicide attempt. Early screening, detection, and management of suicidal behavior, as well as appropriate mental healthcare, are warranted in refugee camps to reduce the number of suicide attempts.

Keywords: suicide attempt, refugee, Eritrea, Tigray, Ethiopia

Introduction

A suicide attempt is an effort made to deliberately harm oneself aimed at ending one’s life, which, however, is non-fatal for various reasons such as intervention by others.1 Most people can be helped in getting through their moment of crisis if they have someone who will spend time with them, listen, take them seriously, and help them to talk about their thoughts and feelings.2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one person dies by suicide every 40 seconds.3 When a person takes their own life, there is a serious psychological, social, and financial impact on at least six other people.4 The WHO estimates that 800,000 people die by suicide each year, with 11.4 deaths per 100,000 globally.5

Suicide does not just occur in high-income countries, but is a global phenomenon in all regions of the world. In fact, over 77% of global suicides occurred in low- and middle-income countries in 2019.6 Suicide attempts are a major global concern, especially in refugee settings.7

The prevalence of attempted suicide among refugees has been variably reported from Germany (7.6%8 and 8.0%9), Europe (10.5%),10 Sri Lanka (11.9%),11 and Ethiopia (4% for 12-month and 4% for lifetime prevalence).12 According to different kinds of literature, factors that are associated with suicide attempts among refugees include current symptoms of trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), family history of mental illness, and hopelessness.13–20

Suicide is one of the priority conditions in the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP), launched in 2008, which provides evidence-based technical guidance for countries to scale up service provision and care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders.6 In the WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030, WHO Member States have committed themselves to working towards the global target of reducing the suicide rate in their countries by one-third by 2030.6

In addition, the suicide mortality rate is an indicator of target 3.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals: by 2030, to reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and well-being. Despite Ethiopia receiving a significant number of refugees annually (from Eritrea), there is little evidence of suicide attempts among refugees. The present study will assess suicide attempts among adult Eritrean Refugees in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among adult Eritrean refugees from February 2020 to April 2020. The study was conducted in the Mai-Aini Eritrean refugee camp, North West Tigray, Ethiopia, which is located at a distance of 367 km from Mekelle, the capital city of Tigray Regional State, and 1150 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. As of December 2018, the Eritrean refugee camp had a total population of 6311 men and 5826 women, of whom some 6830 refugees were adults aged 18–60 years (3850 males, 2980 females). There is one health center, jointly funded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA), providing several health services including mental health services.

Study Population and Sampling Process

The study participants included in the study were adult refugees aged between 18 and 60 years who are living permanently in the Mai-Aini refugee camp. We excluded immigrants with impaired hearing and seriously ill refugees. The sample size was determined using a single proportion calculation formula assuming the following parameters: 50% proportion of participants with a suicide attempt, 95% CI (Ζ1 − α/2) = 1.96, 5% degree of marginal error (d), and 10% non-response rate. Given that the source population is below 10,000, we applied a correction formula,21 and the minimum required sample size was 400. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to recruit study respondents. When two or more eligible participants were present in a household, we selected one eligible participant using a lottery method. The Geneva Convention defines a “refugee” as “someone unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion”.22

Data Collection Process

Data were collected using an interviewer-administered and structured questionnaire from the WHO survey questions. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic and clinically related variables, psychosocial characteristics, and substance use. To establish face validity and translation quality, the questionnaire was tested on 5% of the total sample size determined for this study, on participants outside the study site, by data collectors and supervisors during training. A few questions, language clarity, and information were revised and the questionnaire was finalized for the study. Three data collectors and supervisors were recruited and they were given rigorous training for 2 days. The supervisors followed the process of data collection, checked the consistency of data completeness, and communicated with the principal investigators on a daily basis.

Variable and Measurements

The response variable in the study was a suicide attempt. A suicide attempt was defined as potentially self-injurious behavior with a non-fatal outcome, where the person intended at some level to kill themselves, and was assessed using the question: “Having you ever attempted suicide?”, with response options “Yes (1)” and “No (2)”.23

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) was designed to measure three major aspects of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and expectations. The test is designed for adults and consists of a list of 20 statements. The person is asked to decide about each sentence whether it describes his/her attitude for the past week, including that day. If the statement is false for the person, he/she should write “false” next to it. If the statement is true for the person, he/she should write “true” next to it. Scores of 4–8 indicate mild hopelessness, 9–14 moderate, and 15–20 severe hopelessness. The translation of the BHS was accomplished according to the internationally accepted procedure for scientific measures.24

Current symptoms of traumatic experiences were assessed using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.25

The PTSD screen is a four-item screening instrument that was designed for use in primary care and other settings and is currently used to screen for PTSD. It includes an introductory sentence to cue respondents to traumatic events. The results of the PC-PTSD should be considered “positive” if a patient answers “yes” to any three items.26

Social support was measured using the three-item Oslo Social Support Scale, as “poor”, “intermediate”, or “good”. A sum index may also be generated by summarizing the raw scores, the sum ranging from 3 to 14. A score of 3–8 is “poor support”, 9–11 is “moderate support”, and 12–14 is “strong support”.27

Data Analysis

Data were entered into Epi Info 728 and then exported to SPSS version 20.00 for analysis. We described the socio-demographic, clinically related, and psychosocial characteristics, and substance use-related factors. We performed bivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the crude association between the factors and outcome variables and select candidate variables (variables with a p-value <0.2) for multivariable logistic regression. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% CI was calculated and p-values less than 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression were considered to indicate a significant association.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

A total of 396 respondents participated in the study, giving a response rate of 99%. Out of the total respondents, 232 (58.6%) were in the age range of 25–49 years. Males made up the majority [204 (51.5%)] of the participants, and 215 participants (54.4%) were Christian Orthodox followers. The majority of respondents [271 (68.4%)] had lived in a rural residence in their country of origin. Also, over half of the respondents [206 (52%)] had attended primary education. More than three-fourths of participants [312 (78.8%)] were unemployed, and 217 (54.8%) of the respondents had lived in the camp for less than 5 years. Table 1 demonstrates the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in the study.

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents Among Adults Aged 18–60 Years in Mai-Aini Eritrean Refugee Camp, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia |

Clinical Variables

Table 2 presents the clinical variables. The majority of respondents had no history of trauma [304 (76.8%)], no history of a natural disaster [360 (90.9%)], and no history of major family loss [290 (73.2%)]. On the other hand, 73 respondents (18.4%) had PTSD symptoms, 125 (31.6%) had depression symptoms, 45 (11.4%) had a history of chronic illness, and 45 (11.4%) had a family history of mental disorders.

|

Table 2 Clinical Characteristics of Respondents Among Adults Aged 18–60 Years in Mai-Aini Eritrean Refugee Camp, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia |

Psychosocial and Substance Use-Related Factors

The majority of the respondents had no history of hopelessness [227 (57.3%)], were not lonely [281 (71%)], and had strong social support [234 (59.1%)]. Besides, 66 respondents (16.7%) had a history of ever drinking alcohol, and 47 (11.9%) had ever smoked cigarettes in their lifetime (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Psychosocial and Substance Use-Related Characteristics of Respondents in Mai-Aini Eritrean Refugee Camp, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia |

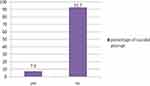

Prevalence of Attempted Suicide

Among the total of 396 adult refugees who participated in this study, 29 (7.3%) had attempted suicide during the stay in the refugee camp (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Percentage distribution of suicide attempts among adults aged 18–60 years in Mai-Aini Eritrean Refugee Camp, Tigray, northern Ethiopia, 2020. |

Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts

Factors that were significantly associated with a suicide attempt included a history of trauma, family history of mental disorder, history of PTSD, and severe hopelessness (Table 4). Refugees with a history of trauma were at five times (AOR=5.6, 95% CI: 2.1, 14.9) greater risk of a suicide attempt than those without a history of trauma. Refugees with a family history of mental disorder had a three times (AOR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.01, 9.07) higher risk of a suicide attempt than those who did not have a family history of mental disorder. Those with a history of PTSD symptoms were three times (AOR=2.7, 95% CI: 1.01, 7.4) more likely to have attempted suicide than those with no history of PTSD. Participants who felt severe hopelessness also had a higher risk (AOR=3.9, 95% CI: 1.3, 12.7) of attempting suicide than those with no feelings of hopelessness (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Prevalence of Suicide Attempts and Associated Factors at Mai-Aini Eritrean Refugee Camp, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia |

Discussion

The present study determined the prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts among adult Eritrean refugees in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. The prevalence of suicide attempts among participants was 7.3% (95% CI: 4.8%, 9.8%), and this is in line with several studies conducted in Germany, which reported rates of 7.6%,8 8.0%,9 9.0%,29 and 6.5%,30 and a meta-analysis of community studies, which reported a rate of 6%.31

The prevalence of attempted suicide in our study was lower than findings from studies in Europe, with an average rate of 10.5%,10 and Sri Lanka, at 11.9%.11 But the present finding is higher than that seen in studies conducted in the general population of Ethiopia (4% for 12-month and 4%, for lifetime prevalence),12 in the European general population (0.57% for 12-month and 2.88% for lifetime prevalence),32,33 and in China (0.2% for 12-month and 0.8% for lifetime prevalnce),34 as well as being higher than the lifetime pooled prevalence across 17 countries (2.7%).35

The possible difference from the previous studies may be due to social and financial problems, and that the United Nations (UN) and aid organizations do not pay attention to the emotional and mental health of refugees because their focus is typically on food, shelter, and physical diseases. In addition, in Ethiopia, there is a strong social support system for families following a natural death; yet, fears associated with stigma, cultural taboos, and cultural criticism affect the community’s attitude, practices, and help-seeking behaviors.

There are several predictive variables for a suicide attempt in our study. Our study revealed that participants who had a history of trauma were two times more likely to have attempted suicide than those who had not experienced trauma. This finding was supported by studies conducted in Canada,13 the UK,14 and Australia,15 but was inconsistent with findings from the USA5,17 and Europe.18,36

These discrepancies could be due to a lack of knowledge, training, and experience among immigration officials. Concerning this, the current study found that participants who had a family history of mental disorder and a history of PTSD were more likely to have attempted suicide than those who had not, as also found in Canada,13 the UK,14 and Australia.15

Consistent with the results of studies from Jordan, the USA, and Sweden,16,37–39 the present study also found that participants who had a history of chronic illness were more likely to have attempted suicide than those who had no chronic illness. Karasouli et al19 explored how chronic illnesses could lead to suicide attempts. They found that people with chronic physical illness suffer from pain, disfigurement, disability, and an invasive treatment regimen. This leads to their having a compromised quality of life to the extent that the pain is unbearable or living with the illness is intolerable, and these patients may deliberately not comply with their medication, and could subsequently consider suicide as a very real possibility.19 Health workers should be alert to intentional non-adherence as it may end a patient’s life. We also found that participants who felt severe hopelessness were three times more likely to have attempted suicide than those who did not have a feeling of severe hopelessness, as also revealed in other studies.20,40 Evidence shows that people who feel hopelessness have lost their purpose for living and the meaning in their life, and this can cause several mental illnesses leading to serious suicide attempts.41 It is crucial to recognize such signs and symptoms of hopelessness or demoralization and understand the suffering of people in clinical practice, in order to develop suicide prevention programs.

The study has a few limitations. Given the quantitative nature of the study, data on sensitive issues or topics may be distorted based on cultural grounds and the self-reported nature of information in the study. Furthermore, the potential reasons and mediators leading to a suicide attempt could not be explored. The use of a cross-sectional approach also means that causal relationships could not be determined. The respondents may not have been assured that their answers would be treated with confidence and may have felt that reporting their use of alcohol, chat, or cigarettes could have harmed their standing in some way.

Conclusions

This study showed that during the stay in the refugee camp there was a high prevalence of suicide attempts compared to the prevalence of suicide attempts among the general populations of Ethiopia, Europe, and China, and to the lifetime pooled prevalence across 17 countries. We found the following predictors for a suicide attempt: history of trauma, level of hopelessness, family history of mental disorder, and history of PTSD. The following recommendations are important to reduce the rate of suicide attempts: 1) ongoing professional development and training should be provided to healthcare workers to identify signs of mental disorders, PTSD, and demoralization/hopelessness, in order to provide appropriate services or referrals; 2) there should be integrated screening to all service provision sites for mental health disorders (PTSD, depression, chronic illness) in outpatient departments; 3) a comprehensive multi-sector suicide prevention strategy is needed; and 4) health information and awareness about the causes of or factors in suicide attempts should be provided in schools and workplaces on a regular basis.

Abbreviations

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ARRA, Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odds ratio; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; UN, United Nations; UNHCR, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

All relevant data are contained within the paper. The SPSS data of individual patients are not permitted to be provided to other bodies, as outlined by the ethics committee who approved the study. However, Teferi ([email protected]) can provide an anonymized data set for researchers who need further clarification.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee (IRB number: IRB I79/2020) of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Aksum. A permission letter was obtained from the zonal office and refugee camp before data collection. A letter of cooperation from the kebele’s administrators was also secured. Finally, written and verbal informed consent was obtained from every study participant included in the study during the data collection time, after explaining the objectives of the study and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The study participants included were aged between 18 and 60 years. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki).

Acknowledgments

We are highly indebted to all participants of the study, supervisors of data collection, and data collectors for their worthy efforts and participation in this study. We are also thankful to the administrative bodies at all levels who endorsed the undertaking of this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding Suicide: Fact Sheet. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015.

2. De Silva SA, Colucci E, Mendis J, Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Minas H. Suicide first aid guidelines for Sri Lanka: a Delphi consensus study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s13033-016-0085-3

3. World Health Organization. Suicide: one person dies every 40 seconds; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds.

4. Bitew H, Andargie G, Tadesse A, Belete A, Fekadu W, Mekonen T. Suicidal ideation, attempt, and determining factors among HIV/AIDS patients, Ethiopia. Depress Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–6. doi:10.1155/2016/8913160

5. Meyerhoff J, Rohan KJ, Fondacaro KM. Suicide and suicide-related behavior among Bhutanese refugees resettled in the United States. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):270. doi:10.1037/aap0000125

6. World Health Organization. Suicide. World Health Organization; 2021.

7. Scott A, Guo B. For Which Strategies of Suicide Prevention is There Evidence of Effectiveness. Denmark: World Health Organization; 2012.

8. Donath C, Bergmann MC, Kliem S, Hillemacher T, Baier D. Epidemiology of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and direct self-injurious behavior in adolescents with a migration background: a representative study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1404-z

9. Brunner R, Parzer P, Haffner J, et al. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(7):641–649. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.7.641

10. Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Arapaki A, Richardson C. Adolescents’ self‐reported suicide attempts, self‐harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2012;53(4):381–389. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02457.x

11. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–2236. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324

12. Bifftu BB, Tiruneh BT, Dachew BA, Guracho YD. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in the general population of Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s13033-021-00449-z

13. Gojer J, Ellis A. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the Refugee Determination Process in Canada: Starting the Discourse. UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service; 2014.

14. Cohen J. Safe in our hands?: a study of suicide and self-harm in asylum seekers. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15(4):235–244. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.11.001

15. Brough M, Gorman D, Ramirez E, Westoby P. Young refugees talk about well‐being: a qualitative analysis of refugee youth mental health from three states. Austra J Soc Issues. 2003;38(2):193–208. doi:10.1002/j.1839-4655.2003.tb01142.x

16. Darvishi N, Farhadi M, Haghtalab T, Poorolajal J. Alcohol-related risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126870. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126870

17. Wenzel T, Griengl H, Stompe T, Mirzaei S, Kieffer W. Psychological disorders in survivors of torture: exhaustion, impairment and depression. Psychopathology. 2000;33(6):292–296. doi:10.1159/000029160

18. Médicins Sans Frontières. Confronting the Mental Health Emergency on Samos and Lesvos: Why the Containment of Asylum Seekers on the Greek Islands Must End. Athens: Médicins Sans Frontières; 2017.

19. Karasouli E, Latchford G, Owens D. The impact of chronic illness in suicidality: a qualitative exploration. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):899–908. doi:10.1080/21642850.2014.940954

20. Wolfenden LL. Parental Psychosis: Exploring Emotional and Cognitive Processes and the Feasibility of a Parenting Intervention. The University of Manchester (United Kingdom); 2019.

21. Israel GD. Determining sample size. 1992.

22. Verroken S, Schotte C, Derluyn I, Baetens I. Starting from scratch: prevalence, methods, and functions of non-suicidal self-injury among refugee minors in Belgium. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(1):51. doi:10.1186/s13034-018-0260-1

23. García-Vega E, Camero A, Fernández M, Villaverde A. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in persons with gender dysphoria. Psicothema. 2018;30(3):283–288. doi:10.7334/psicothema2017.438

24. Osman A, Downs WR, Kopper BA, et al. The reasons for living inventory for adolescents (RFL‐A): development and psychometric properties. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54(8):1063–1078. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1063::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-Z

25. Afewerki Haylom F. Depression among Eritrean immigrants in OSLO and surrounding areas: associated factors. 2017.

26. Cameron RP, Gusman D. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatr. 2003;9(1):9–14.

27. Kocalevent R-D, Berg L, Beutel ME, et al. Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s40359-018-0249-9

28. Dean AG, Dean JA, Burton AH, Dicker RC. Epi Info: a general-purpose microcomputer program for public health information systems. Am J Prev Med. 1991;7(3):178–182. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30936-X

29. Donath C, Graessel E, Baier D, Bleich S, Hillemacher T. Is parenting style a predictor of suicide attempts in a representative sample of adolescents? BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-113

30. Plener PL, Libal G, Keller F, Fegert JM, Muehlenkamp JJ. An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychol Med. 2009;39(9):1549–1558. doi:10.1017/S0033291708005114

31. Dong M, Zeng L-N, Lu L, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempt in individuals with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of observational surveys. Psychol Med. 2019;49(10):1691–1704. doi:10.1017/S0033291718002301

32. Bernal M, Haro JM, Bernert S, et al. Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: results from the ESEMED study. J Affect Disord. 2007;101(1–3):27–34. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.018

33. Castillejos MC, Huertas P, Martín P, Moreno Kuestner B. Prevalence of suicidality in the European general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archiv Suicide Res. 2020;25:1–19.

34. Lee S, Fung S, Tsang A, et al. Lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt in metropolitan China. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(6):429–437. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01064.x

35. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatr. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113

36. Demetry Y. Suicidal ideation and attempt among immigrants in Europe: a literature review. 2014.

37. Amer NRY, Hamdan-Mansour AM. Psychosocial predictors of suicidal ideation in patients diagnosed with chronic illnesses in Jordan. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(11):864–871. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.917752

38. Daniels SR, Jacobson MS, McCrindle BW, Eckel RH, Sanner BM. American Heart Association childhood obesity research summit report. Circulation. 2009;119(15):e489–e517. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192216

39. Leiler A, Hollifield M, Wasteson E, Bjärtå A. Suicidal ideation and severity of distress among refugees residing in asylum accommodations in Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2751. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152751

40. Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(2):187. doi:10.1037/bul0000084

41. Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, et al. The role of demoralization and hopelessness in suicide risk in schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2019;55(5):200. doi:10.3390/medicina55050200

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.