Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 8

Student-led widening access schemes

Received 17 April 2017

Accepted for publication 15 June 2017

Published 9 August 2017 Volume 2017:8 Pages 581—585

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S139836

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Utkarsh Ojha, Shivam Patel

Imperial College School of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK

Abstract: Medicine is among the most competitive degrees in the UK. Successfully gaining admission into medical school requires students to demonstrate a variety of academic and nonacademic skills in addition to experience and insights into the profession. However, gaining relevant experience within medicine may not be equally available to all students. The 2012 report from the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission stated that in terms of widening access and improving social mobility “medicine lags behind other professions”. As president and vice president of Imperial College School of Medicine’s student-led widening access society, we can provide an insight into the role of medical students in leading widening participation programs within a large medical school. In this article, we discuss our organizational structure, our core activities and our collaboration with the university’s outreach program.

Keywords: widening access, medical school, social inequality

Introduction

Gaining admission into medical school has always been a competitive process. In 2016, there were 20,100 students who applied via University and Colleges Admission Service (UCAS) for medicine courses in the UK for approximately 8,000 places.1 The application process for medicine is long and requires students to demonstrate a variety of academic and nonacademic skills in addition to experience and insight into the profession.2 However, gaining such relevant experience may not be equally accessible to all students. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the social disparity which exists in medical school. Gallagher et al3 reported that successful applicants for medicine are more likely to be from higher social class. Similarly, Houston et al4 described that students’ chances of gaining admission into medical school are increased by applying with good grades after attending private school. It has also been suggested that candidates from ethnic minorities are at a more disadvantage than their peers.5 The General Medical Council’s (GMC) “Tomorrow’s Doctors” outlines that medical schools should ensure that “all applicants and students are treated fairly and with equality of opportunity, regardless of their diverse backgrounds.”6 As a result, medical schools employ various instruments for fair selection, including aptitude tests, personal statements, academic references and interviews.7,8 Despite these efforts, a recent study reported that students from low socioeconomic status groups remain underrepresented in UK medical schools.9 The study highlighted that applicant residents in the most deprived areas and attending nonselective state schools were less likely to obtain an accepted offer for medicine. Furthermore, the 2012 report from the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission stated that in terms of widening access and improving social mobility, “medicine lags behind other professions.”10,11

As the current selection procedure is considerably failing to close the socioeconomic disparity at medical schools, governments have requested for the medical selection system to be reviewed.12 In response to this issue, many universities run widening participation schemes, which aim to address the discrepancies between different social groups at university and remove barriers faced by students from underrepresented backgrounds.13

The GMC’s “Good Medical Practice” guides future doctors to “contribute to teaching and training doctors and students” and encourages them to “take on a mentoring role.”14 In accordance with these guidelines, the student body of Imperial College School of Medicine (ICSM) established a widening participation society, “ICSM Vision.” Vision provides resources and supports students from underprivileged background who are aiming to study medicine at university by hosting various events throughout the year. Vision was founded in 2007 and soon built up a reputation by more than doubling in capacity since its establishment to cater for over 500 students annually.15 The society is widely recognized for its work, having featured in “British Medical Association widening access to medicine guide,” and was nominated for society of the year at the UK Medical Student Association Conference 2011. As president and vice president of the 2016–2017 ICSM Vision Committee, we can provide an insight into the role of medical students in leading widening participation programs within a large medical school. In this article, we discuss our organizational structure, our core activities and our collaboration with the university’s outreach program.

Organizational structure

Vision is entirely student led, with a core committee of 20 current Imperial College medical students forming the organizing committee. The structure of the committee consists of a senior (executive) team made up of 7 students, and a wider (general) committee made up of 13 (Figure 1). The committee is elected at the annual general meeting in advance of the academic year they will serve.

| Figure 1 Hierarchy of the ICSM Vision Committee. Abbreviation: ICSM, Imperial College School of Medicine. |

The executive committee consists of the president, who is responsible for the overall management of the society and enduring the activities operate smoothly, and will be assisted by a vice president. The senior conference chair, junior conference chair and roadshow chair are responsible for managing their respective activities. In addition, the secretary is responsible for organizing bookings and communicating with schools and the treasurer is responsible for financial matters. The general committee consists of several students, each responsible for a specific aspect of organizing activities, such as catering or sponsorship.

A structured committee has many advantages for a student-run outreach society. First, it allows the division of labor given the stresses and constant pressure of medical school, a single person would not be able to handle the large amount of work needed to run such a society. Having set roles and a hierarchy is the most efficient way to manage this workload.16 Second, a concern of many is that student-led outreach societies will die out over time as students graduate and leave the university. The mandatory handovers that occur every year are absolutely vital to ensuring the continuity of Vision’s activities each year. Finally, junior committee members, usually those newer to Vision, are given numerous responsibilities in planning events and in managing them on the day itself, this maximizes their exposure and ensures they are ready to lead in future years.

Core events and activities

ICSM Vision runs two large conferences (Figure 2) each year, as well as a number of smaller events throughout the year through the Vision roadshow program.

| Figure 2 Conference day. |

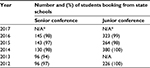

The general committee contacts state schools, within the catchment area, and informs them of our upcoming events. Prospective delegates from these schools send in their application form; priority is given to students attending from state schools. If places are not filled up, then the event is advertised to students from independent schools (Table 1).

The senior conference is aimed for year 13 students and is held in September, just prior to the submission of UCAS applications. The day consists of a series of talks from distinguished members of the medical profession. Previously, physicians, surgeons and senior medical students have given talks on “life as a junior doctor,” “life as a surgeon” and “life as a medical student,” although in response to feedback the shift has focused onto increasing the provision of small group teaching on medical school entrance examinations and personal statement writing. Medical students also deliver tutorials on medical ethics, aimed at preparing pupils for ethics and law-related questions at the admission interview, topical issues in health care, and guide students on how to best prepare for their interviews. To ensure that the program is not restricted to one university, Vision invites representatives from medical schools across the country to host stands and answer pupil’s question about the admission process of their medical school. The conference receives considerable help of over 100 medical students and alumni of ICSM who volunteer as tutors and general helpers for the day.

The junior conference is similar to senior on an operational level. However, the junior conference aims to inspire and inform younger years, particularly students from years 10, 11 and 12 about the medical profession and the medical school application process. The conference consists of similar talks as the senior conference, although focuses more on inspiring pupils to pursue a career in medicine than detailed advice on the application process. In the past, the junior conference has hosted alumni working as foundation program and core training doctors, who have given their personal insight into life as a doctor. The day also allows students to participate in case scenarios based around various aspects of medicine, including cardiology, respiratory, neurology and clinical communications. In these sessions, students are introduced to basic medical instruments and have a chance to try practical skills such as heart auscultation, blood pressure measurement and neurological reflexes. In 2016, the junior conference launched a 1000-word essay competition for students to enter prior to the event. The focus of the essay was on a topical issue regarding the financial pressures on the National Health Service. A handful of essays were shortlisted and sent to a senior faculty member, who selected the final winners. The introduction of the essay competition allowed delegates to engage in current medical affairs and take time to research and practice their academic skills. Winners and runners up were awarded prizes on the day of the conference.

The roadshow program consists of school visits made by Imperial College medical students to nonselective state schools within London. Teachers and career advisers can contact the roadshow chair, who will confirm the suitability of the school and advertise out to the many medical student members of Vision, and any volunteers are put in contact with the school and a visit arranged. Teachers can choose the particular topic or content they wish for the student to cover, and common themes include hosting a mock interview session for pupils with upcoming interviews and holding talks or lectures on medicine as a career or how to be successful in medical school admissions.

In previous years, it has been challenging to track how many students from disadvantage schools, who attend Vision’s conference or roadshow program, gain admission into medical schools. This is mainly because students fail to keep in touch after the event. This year, Vision introduced a postconference survey to keep track of students’ progress in the application process and provide ongoing support if required.

Pathways to medicine scheme

In 2014, Vision began collaboration with the faculty’s outreach program, “Pathways to Medicine.” The program is co-funded by the Sutton Trust and also supported by Health Education England and the Medical Schools Council.2

As part of this scheme, 60 year 11 pupils are selected to form a cohort that will, through their further studies, be given access to help and activities intended to prepare them for medical school applications.2 These resources include access to the junior and senior conferences and to a separate entrance examination and interview workshop. Unlike many other medical widening participation schemes, Vision follows a model of an entirely student-led society which provides a service to the faculty.

Conclusion

Vision provides a unique model of medical school outreach in the UK: an entirely student-led scheme, hosting two large events and many smaller workshops and collaborating with other groups within the university and beyond. Student-led schemes, in the authors’ opinion, provide a more relaxed and flexible approach to widening participation, and being run by motivated and enthusiastic students allows for them to thrive. It is conceivable that such a model could be set up at other medical schools currently lacking such schemes and possibly abroad to help narrow the disparity in socioeconomic backgrounds at medical school.

Acknowledgment

SP served as the president of ICSM Vision Society for the academic year 2016–2017. UO served as the vice president of ICSM Vision Society for the academic year 2016–2017.

Author contributions

UO and SP were involved in the conception, design, drafting, revision and final approval of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Rebekkah Morris. The Medical School Application Guide. 2017. Available from: http://themsag.com/blog/competition-ratios.html. Accessed April 11, 2017. | ||

Kevin Murphy. How Can We Widen Access to Medicine? 2017. Available from: http://www.endocrinology.org/endocrinologist/121-autumn16/features/how-can-we-widen-access-to-medicine/. Accessed April 11, 2017. | ||

Gallagher J, Niven V, Donaldson N, Wilson N. Widening access? Characteristics of applicants to medical and dental schools, compared with UCAS. Br Dent J. 2009;207(9):433–445. | ||

Houston M, Osborne M, Rimmer R. Private schooling and admission to medicine: a case study using matched samples and causal mediation analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:136. | ||

McManus IC. Factors affecting likelihood of applicants being offered a place in medical schools in the United Kingdom in 1996 and 1997: retrospective study. BMJ. 1999;318(7176):94–94. | ||

General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education; 2009. Available from: www.gmc-uk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_1214.pdf_48905759.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2017. | ||

Tiffin PA, Dowell JS, McLachlan JC. Widening access to UK medical education for under-represented socioeconomic groups: modelling the impact of the UKCAT in the 2009 cohort. BMJ. 2012;344:1805. | ||

Steele K. Selecting tomorrow’s doctors. Ulster Med J. 2011;80(2):62–67. | ||

Steven K, Dowell J, Jackson C, Guthrie B. Fair access to medicine? Retrospective analysis of UK medical schools application data 2009–2012 using three measures of socioeconomic status. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:11. | ||

Medical Schools Council. Selecting for Excellence: Final Report; 2014. Available from: http://www.medschools.ac.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Selecting-for-Excellence-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2017. | ||

Bedi R, Gilthorpe M. Recruitment: social background of minority ethnic applicants to medicine and dentistry. Br Dent J. 2000;189(3):152–154. | ||

Cleland J, Dowell J, McLachlan J, Nicholson S, Patterson F. Identifying Best Practice in the Selection of Medical Students. London: General Medical Council; 2012. | ||

Dearing R. Higher Education in the Learning Society (The Dearing Report). London: The National Committee of Enquiry into Higher Education; 1997. | ||

General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice; 2013. Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice/teaching_training.asp. Accessed March 2, 2017. | ||

Vision [homepage on the Internet]. Imperial College School of Medicine Students’ Union Vision Society. About Us. 2017. Available from: http://www.icsmvision.co.uk/. Accessed April 11, 2017. | ||

Mann S. Unleashing your leadership potential: seven strategies for success. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2012;33(7):705–706. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.