Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 15

Statin Use and the Risk of Subsequent Hospitalized Exacerbations in COPD Patients with Frequent Exacerbations

Authors Lin CM , Yang TM , Yang YH , Tsai YH, Lee CP, Chen PC , Chen WC, Hsieh MJ

Received 28 August 2019

Accepted for publication 10 January 2020

Published 10 February 2020 Volume 2020:15 Pages 289—299

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S229047

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Chunxue Bai

Chieh-Mo Lin, 1, 2 Tsung-Ming Yang, 1 Yao-Hsu Yang, 3–5 Ying-Huang Tsai, 6, 7 Chuan-Pin Lee, 4 Pau-Chung Chen, 8–11 Wen-Cheng Chen, 12 Meng-Jer Hsieh 1, 7

1Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Chiayi, Taiwan; 2Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan; 3Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Chiayi, Taiwan; 4Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Chiayi, Taiwan; 5School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 6Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 7Department of Respiratory Therapy, School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 8Institute of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, National Taiwan University College of Public Health, Taipei, Taiwan; 9Department of Public Health, National Taiwan University College of Public Health, Taipei, Taiwan; 10Department of Environmental and Occupational Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital and National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan; 11Office of Occupational Safety and Health, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; 12Department of Radiation Oncology, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Chiayi, Taiwan

Correspondence: Meng-Jer Hsieh

Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, No. 6, West Sec., Jiapu Road, Puzi City, Chiayi County 61363, Taiwan

Tel +886-5-3621000

Email [email protected]

Rationale: The potential benefits of statins for the prevention of exacerbations in patients with COPD remains controversial. No previous studies have investigated the impact of statins on clinical outcomes in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations.

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the association between the use of statins and the risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in COPD frequent exacerbators.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a population-based cohort study using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. 139,223 COPD patients with a first hospitalized exacerbation between 2004 and 2012 were analyzed. Among them, 35,482 had a second hospitalized exacerbation within a year after the first exacerbation, and were defined as frequent exacerbators. 1:4 propensity score matching was used to create matched samples of statin users and non-users. The competing risk regression analysis model was used to evaluate the association between statin use and exacerbation risk.

Results: The use of statins was associated with a significantly reduced risk in subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in COPD patients after their first hospitalized exacerbation (adjusted subdistribution hazard ration [SHR], 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85– 0.93, P< 0.001). In frequent exacerbators, the SHR for subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in statins users was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81– 0.94, P=0.001). Subgroup analysis among frequent exacerbators demonstrated that the use of statins only provided a protective effect against subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in male patients aged 75 years and older, with coexisting diabetes mellitus, hypertension or cardiovascular disease, and no protective effect was observed in those with lung cancer or depression. Current use of statins was associated with a greater protective effect for reducing subsequent hospitalized exacerbation.

Conclusion: The use of statins was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalized exacerbations in COPD patients after a first hospitalized exacerbation and in specified COPD frequent exacerbators.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, statin, exacerbation, frequent exacerbator

Summary at a Glance

The benefits of statins for the prevention of exacerbations in patients with COPD remains controversial. This is the first study to observe a reduced risk of hospitalized exacerbations with the use of statins in frequent exacerbators of COPD in a real-world setting. The use of statins was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalized exacerbations in COPD patients after the first hospitalized exacerbation and in specified COPD frequent exacerbators.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Exacerbations of COPD can lead to hospitalization, worsening lung function, worsening quality of life, and increased mortality.1–4 A higher frequency of COPD exacerbations has been associated with worse disease progression, a higher risk of further exacerbations and hospitalization, and mortality.5–8 Therefore, the “frequent exacerbator” is recognized as an important phenotype in patients with COPD. In recent years, there has been a growing understanding of systemic inflammation in patients with COPD.9–11 Frequent exacerbators have been shown to have higher levels of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) during their exacerbation recovery period.12 Therefore, new therapeutic strategies to reduce systemic inflammation might play a role in the prevention of recurrent exacerbations in COPD patients.

Statins have been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.13–18 The use of statins has also been shown to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular outcomes.19–21 Observational studies have demonstrated that the use of statins may reduce the risk of exacerbations,22–25 as well as lung-related and all-cause mortality26–29 in patients with COPD. Nevertheless, another observational study demonstrated that statins may only be associated with a decreased risk of exacerbations in patients with COPD with comorbid cardiovascular disease.30 Although observational studies have reported that statins have a beneficial effect on the prevention of COPD exacerbations, a large randomized trial reported that simvastatin treatment had no effect on exacerbation rates or the time to a first exacerbation in patients with COPD.31 In patients with COPD, the potential effects of statins remain controversial.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the impact of statins on clinical outcomes in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the potential association between the use of statins and the risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations in a real-world setting.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

The present population-based observational retrospective cohort study was conducted using medical claims data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan. The NHIRD contains registration files and original claims data, including details of all medical and pharmacy claims from hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and emergency services. Access to and the use of the database for the current study was approved by the National Health Research Institute. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Taiwan (approval number: 103-2966B).

Study Population and Design

Subjects who had a diagnosis code for COPD (ICD-9 codes 491, 492, and 496) in the NHIRD in at least six outpatient visits or one hospitalization from January 1997 to December 2010 were eligible for inclusion within the current study. These patient’s data were retrieved from the NHIRD for analysis. A hospitalized exacerbation was defined as a primary discharge diagnosis code for COPD with at least one prescription for respiratory antibiotics or systemic steroids during the hospital admission. Those without a prescription for any COPD medication before enrolment, including beta agonists, ipratropium bromide, tiotropium, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or xanthins, were excluded from the study. Patients with a first COPD hospitalized exacerbation between January 2004 and December 2012 were selected for analysis, because the major maintenance medications for COPD, the combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA), and the first long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), were available for prescription in Taiwan from 2001 and 2003, respectively.

Propensity score matching was performed for gender, age, urbanization, income level, comorbidities and medications with ratio matching of 1 (statin users) to 4 (statin non-users). A total of 9462 statin users and 37,848 non-users were included in the matched cohort, which was classified as cohort 1. Patients with a second hospitalized exacerbation within 1 year of their discharge from the first hospitalization were selected as frequent exacerbators. Again, 1:4 propensity score matching was used, and 2116 statin users and 8464 non-users were included the matched cohort, which was classified as cohort 2. The index dates for cohorts 1 and 2 were the dates of discharge from the first and second hospitalized exacerbations, respectively. The study cohorts were further classified into statin users and non-users. The pre-index period for each cohort was 1 year before the index date, and this was used to determine baseline characteristics and statin exposure. The post-index period included a variable-length follow-up period to a maximum of 1 year, during which the study outcomes were assessed. These two study cohorts were followed from the index date to the occurrence of a hospitalized exacerbation, discontinuation of enrolment in the NHI program, the end of the 1-year follow-up period, or the end of the study period (December 31st 2013), whichever came first.

Exposure Measurements

Patients who received statin prescriptions for a cumulative defined daily dose (cDDD) for more than 28 days within the 365 days prior to the index date, were defined as statin users. Those who used statins for less than 28 cDDD days before the index date were defined as statin non-users. To evaluate the association between the total dosage of statins and the study outcomes, statin users were categorized into two groups according to their cDDD: 28–83, and ≥84. In addition, the use of statins was further categorized as current use (≤180 days) and past use (>180 days) according to the end of the most recent prescription before the index date.

Potential Confounders

Potential confounding risk factors for COPD were defined as the following comorbidities recorded during the enrolment period: cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and diabetes mellitus. Information on other medications that may have affected the risk of COPD exacerbation was also collected, this included LAMA, ICSs, ICS/LABA combinations, acetylcysteine, oral corticosteroids, respiratory antibiotics, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), and aspirin. In addition, sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, income, and level of urbanization) of the patients were also collected.

Statistical Analysis

The demographic factors and the proportions of comorbidities between the statin users and non-users were compared. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables. The incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in each cohort were calculated for the 1-year follow-up period. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of hospitalized exacerbations. The Log rank test was performed to examine differences in the risk for subsequent hospitalized exacerbations. Death was considered to be a competing event prior to subsequent exacerbation and the competing risk regression model was applied as described by Austin and Fine,32 to estimate the subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) of subsequent hospitalized exacerbation for the matched cohorts and subgroups. Adjusted SHRs were calculated by controlling for demographic data and confounding factors, including gender, age, urbanization, income, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, osteoporosis, depression and medications. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Sensitivity Analyses

Many medications have shown positive effects on the prevention of COPD exacerbations. To evaluate potential effect modifiers, analyses were stratified by groups with and without the use of long- or short-acting bronchodilators, ICSs, acetylcysteine, oral corticosteroids, respiratory antibiotics, cardioselective and non-cardioselective beta-blockers, ACEI, and aspirin. Outcomes were also stratified by groups according to sex, age, and those with or without diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer. These sensitivity analyses were used to evaluate the difference and consistency between the use of statins and the risk of COPD exacerbations.

Results

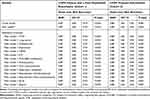

As shown in Figure 1A and B, there were a total of 139,223 patients who had their first hospitalized exacerbation between 2004 and 2012 were selected for analysis. After 1:4 propensity score matching, 9462 statin users and 37,848 non-users were included in cohort 1. Among the patients with a first hospitalized exacerbation, 35,482 patients had a second hospitalized exacerbation within 365 days after being discharged for their first exacerbation and were defined as frequent exacerbators. After propensity score matching, 2116 statin users and 8464 non-users were included in the matched cohort, which was classified as cohort 2. The basic demographic characteristics of the patients after propensity score matching are summarized in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics of COPD Patients After Propensity Score Matching |

Statin Use and the Risk of Hospitalized Exacerbations

Table 2 shows that the use of statins was associated with a significantly reduced risk (adjusted SHR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85–0.93, P<0.001) of a subsequent hospitalized exacerbation after the first hospitalized exacerbation of COPD. In the frequent exacerbators of COPD group, the use of statins was associated with a significantly reduced risk (adjusted HR, 0.88, 95% CI, 0.81–0.94, P=0.001) of a subsequent hospitalized exacerbation. Figure 2A and B illustrate the results of the Kaplan-Meier method for cohorts 1 and 2. The Log rank test revealed a significant difference over the entire Kaplan-Meier curve.

|

Table 2 Adjusted Subdistribution Hazard Ratios (SHRs) for the Development of Subsequent Hospitalized Exacerbations for COPD Patients Associated with Statin Use in Propensity Score Matched Cohorts |

Sensitivity Analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis adjustments; this revealed a significant association between the use of statins and a reduced risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations according to different models in patients in cohort 1 (with a first exacerbation), except for those with female gender, those under 55 years of age, without hypertension, and those coexisting with lung cancer or osteoporosis. In the frequent exacerbators of COPD (cohort 2), the use of statins provided a protective effect against subsequent hospitalized exacerbations only in male patients aged 75 years and older coexisting with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease, except for those patients with lung cancer or depression. Stratified analyses revealed that the protective effect of statins remained in frequent exacerbators with and without the concomitant use of ICS/LABA combination, acetylcysteine, oral corticosteroids, cardioselective beta-blockers, ACEIs and aspirin, but did not remain for those who used Tiotropium, inhaled corticosteroids, respiratory antibiotics, or non-cardioselective beta-blockers.

|

Table 3 Adjusted Subdistribution Hazard Ratios (SHRs) for the Subsequent Hospitalized Exacerbations in COPD Patients in Subpopulations Treated with Statins in Propensity Score Matched Cohorts |

Dosage and Recency of Statin Use

Table 4 demonstrates that the use of statins reduced the risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in a dose-dependent manner in COPD patients with a first exacerbation (cohort 1). However, the dose-dependent effect of statins was not significant in the frequent exacerbators of COPD. Although the use of statins was associated with a reduced risk in COPD exacerbations, the decreased risk appeared to vary according to the recency of statin use. Current use of statins was associated with a greater reduced risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations, whereas there was no statistically significantly decreased risk for past users of statins in COPD frequent exacerbators.

|

Table 4 Adjusted Subdistribution Hazard Ratios (SHRs) for Subsequent Hospitalized Exacerbation According to Dosage and Recency of Statin Use in Propensity Score Matched Cohorts |

Discussion

In the present population-based study, it was found that the use of statins was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in patients with COPD after a first exacerbation. In the frequent exacerbators of COPD, the use of statins provided a protective effect against subsequent hospitalized exacerbations only in male patients aged 75 years and older coexisting with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease, except for those patients with lung cancer or depression. Furthermore, current statin use was associated with a greater reduced risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to observe a reduced risk of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations with the use of statins in patients with frequent exacerbations.

Wang et al used administrative data from the NHIRD to demonstrate that any use of statins was associated with a 30% decreased risk of COPD exacerbations.22 However, their study cohort comprised of only 14,316 patients diagnosed with COPD and 1584 cases with COPD exacerbations. Our study included a larger study population of patients diagnosed with COPD (1,565,248 patients), and 139,223 patients with a first hospitalized exacerbation for COPD were identified. In addition, the impact of statins on clinical outcomes in the frequent exacerbators of COPD had not been previously investigated. Our study was the first to demonstrate a reduced risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbation with the use of statins in frequent exacerbators of COPD.

Although previous observational studies have reported that statins may reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations, this evidence has been questioned due to the negative results of the STATCOPE trial, which showed no association between the use of statins and COPD exacerbations.31 However, that prospective study was questioned because the exclusion criteria for the study participants led to decreased generalizability of the results.33,34 Patients in that study were excluded if they were taking statins previously or had any indications for receiving statins. Excluding these patients may lead to a situation where patients with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular comorbidities were excluded from the trial.33 In our study, a large proportion of the patients with COPD had cardiovascular comorbidities, and systemic inflammation caused by the cardiovascular comorbidity may act synergistically with pulmonary inflammation, especially in frequent exacerbators of COPD, which could partly explain the findings. To eliminate the impact of cardiovascular comorbidities on the protective effects of statins on COPD exacerbations, propensity score matching was performed for gender, age, urbanization, income level, comorbidities and medications. Adjusted SHRs were calculated by controlling for demographic data and confounding factors, including comorbidities and medications.

The stratified analyses found that in frequent exacerbators, the protective effect of statins was not observed in patients without hypertension or cardiovascular disease. The beneficial effect of statin use on exacerbations may be partly explained by a reduction in systemic inflammation, and the findings of the current study indicate that cardiovascular disease and hypertension seemed to play a more important role in systemic inflammation and pulmonary inflammation in frequent exacerbators of COPD compared with patients with a first exacerbation. Ingebrigtsen et al30 reported that statin use was associated with a reduced risk of exacerbations in COPD patients, but had no beneficial effects on exacerbations in those with the most severe COPD without cardiovascular comorbidity, which is consistent with the findings of our study. Therefore, our study suggests that statin treatment is important in patients with COPD, especially in frequent exacerbators with cardiovascular comorbidity. Conversely, statins seemed to provide no beneficial effect for exacerbations in COPD patients with lung cancer. This may be partly explained by the worse outcomes and survival in patients with coexisting COPD and lung cancer. Furthermore, the protective effect of statins was not apparent in frequent exacerbators of COPD who had concomitant use of tiotropium and ICS. In frequent exacerbators of COPD, the use of tiotropium or ICS might provide maximal protective and anti-inflammatory effects for these severe COPD patients and thus statins could have no add-on effect to reduce the risk of further exacerbations. Analyses also found that statin use did not provide beneficial effects in frequent exacerbators of COPD with concomitant use of non-cardioselective beta-blockers, and this finding may be due to the fact that non-cardioselective beta-blockers can result in adverse respiratory effects in COPD patients.

Our study had several strengths. The study was conducted using a national database, which is population-based and includes all patients diagnosed with COPD in Taiwan. To ensure that patients who had diagnostic codes for COPD truly had COPD, patients who did not use any medications for COPD in the previous year before the index date were excluded from the study; thus minimizing the possibility of selection bias. Furthermore, data on the use of medications were obtained from the administrative claims database during the study period, which therefore eliminated the possibility of recall bias.

There are several potential limitations to our study. First, histological data on lung function and the severity of symptoms were not obtained, and therefore it was not possible to assess the severity of COPD. However, the patients included in our study have experienced at least one hospitalized exacerbation of COPD. In addition, the patients in cohort 2 were frequent exacerbators of COPD and were considered more severe than most COPD patients. Second, details on several confounders including smoking, body mass index, and radiologic images, which are associated with the extent of emphysema, were not included in the database. Third, it was not possible to confirm the precise dosage of statins that the study participants actually took. The actual dosage they took may have been overestimated if there was poor-compliance. Furthermore, a possible bias in the study was health behavior bias. A person who regularly receives certain healthcare or medications, has specific lifestyle characteristics that may lead to a decreased risk of exacerbations. Previous study found that patients who adhere to statins are systematically more health seeking than patients who do not remain adherent.35

Conclusions

In conclusion, the use of statins was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalized exacerbations in patients with COPD after a first exacerbation. Current use of statins was associated with a reduced risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations. Meanwhile, the use of statins in frequent exacerbators provided a protective effect against subsequent hospitalized exacerbations only in male patients aged 75 years and older coexisting with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease, except for those patients with lung cancer or depression. Therefore, in frequent exacerbators of COPD, statins may be associated with a reduced risk of hospitalized exacerbations in specified patients.

Abbreviations

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; NHIRD, National Health Insurance Research Database; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; cDDD, cumulative defined daily dose; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; ICS/LABA, Combination of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta agonist, ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory (CLRPG6G0042) for their comments and assistance in data analysis. This study was supported by a grant from Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (grant no. CORPG6D0211).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 Report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(5):557–582. doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP

2. Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2003;124(2):459–467. doi:10.1378/chest.124.2.459

3. Miravitlles M, Ferrer M, Pont A, et al. Effect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 2 year follow up study. Thorax. 2004;59(5):387–395. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.008730

4. Singanayagam A, Schembri S, Chalmers JD. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized adults with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(2):81–89. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201208-043OC

5. Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957–963. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518

6. Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909883

7. Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martinez-Garcia MA, Roman Sanchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–931. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.040527

8. Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–852. doi:10.1136/thorax.57.10.847

9. Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Rabe KF. Systemic manifestations of COPD. Chest. 2011;139(1):165–173. doi:10.1378/chest.10-1252

10. Fabbri LM, Rabe KF. From COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome? Lancet. 2007;370(9589):797–799. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61383-X

11. Agusti A. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what we know and what we don’t know (but should). Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):522–525. doi:10.1513/pats.200701-004FM

12. Perera WR, Hurst JR, Wilkinson TM, et al. Inflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(3):527–534. doi:10.1183/09031936.00092506

13. Kinlay S, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, et al. High-dose atorvastatin enhances the decline in inflammatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the MIRACL study. Circulation. 2003;108(13):1560–1566. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000091404.09558.AF

14. Inoue I, Goto S, Mizotani K, et al. Lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has an anti-inflammatory effect: reduction of MRNA levels for interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, cyclooxygenase-2, and p22phox by regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in primary endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2000;67(8):863–876. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00680-9

15. Davignon J. Pleiotropic effects of pitavastatin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(4):518–535. doi:10.1111/bcp.2012.73.issue-4

16. Wang CY, Liu PY, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statin therapy: molecular mechanisms and clinical results. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(1):37–44. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.004

17. Hothersall E, McSharry C, Thomson NC. Potential therapeutic role for statins in respiratory disease. Thorax. 2006;61(8):729–734. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.057976

18. Bellosta S, Via D, Canavesi M, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors reduce MMP-9 secretion by macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(11):1671–1678. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.18.11.1671

19. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–2207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807646

20. Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b2376. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2376

21. Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD004816.

22. Wang MT, Lo YW, Tsai CL, et al. Statin use and risk of COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization. Am J Med. 2013;126(7):598–606 e592. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.036

23. Blamoun AI, Batty GN, DeBari VA, Rashid AO, Sheikh M, Khan MA. Statins may reduce episodes of exacerbation and the requirement for intubation in patients with COPD: evidence from a retrospective cohort study. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(9):1373–1378. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01731.x

24. Huang CC, Chan WL, Chen YC, et al. Statin use and hospitalization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Clin Ther. 2011;33(10):1365–1370. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.08.010

25. Ajmera M, Shen C, Sambamoorthi U. Association between statin medications and COPD-specific outcomes: a real-world observational study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2017;4(1):9–19. doi:10.1007/s40801-016-0101-6

26. Raymakers AJN, Sadatsafavi M, Sin DD, De Vera MA, Lynd LD. The impact of statin drug use on all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a population-based cohort study. Chest. 2017;152(3):486–493. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.002

27. Soyseth V, Brekke PH, Smith P, Omland T. Statin use is associated with reduced mortality in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(2):279–283. doi:10.1183/09031936.00106406

28. Lawes CM, Thornley S, Young R, et al. Statin use in COPD patients is associated with a reduction in mortality: a national cohort study. Primary Care Respir j. 2012;21(1):35–40. doi:10.4104/pcrj.2011.00095

29. Lahousse L, Loth DW, Joos GF, et al. Statins, systemic inflammation and risk of death in COPD: the Rotterdam study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(2):212–217. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2012.10.008

30. Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P, Hallas J, Vestbo J. Statin use and exacerbations in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2015;70(1):33–40. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205795

31. Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SD, et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2201–2210. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403086

32. Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting fine-gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36(27):4391–4400. doi:10.1002/sim.v36.27

33. Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Agusti A. Statins as adjunct therapy in COPD: how do we cope after STATCOPE? Thorax. 2014;69(10):891–894. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205814

34. Mancini GB, Road J. Are statins out in the COLD? The STATCOPE trial. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(8):970–973. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.03.016

35. Dormuth CR, Patrick AR, Shrank WH, et al. Statin adherence and risk of accidents: a cautionary tale. Circulation. 2009;119(15):2051–2057. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.824151

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.