Back to Journals » Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology » Volume 9

Splenosis involving the gastric fundus, a rare cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report and review of the literature

Authors Reinglas J, Perdrizet K, Ryan SE, Patel RV

Received 5 July 2015

Accepted for publication 9 November 2015

Published 22 September 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 301—305

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S91835

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Andreas M. Kaiser

Jason Reinglas,1 Kirstin Perdrizet,1 Stephen E Ryan,2 Rakesh V Patel1

1Department of Medicine, 2Department of Diagnostic Imaging, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Abstract: Splenosis, the autotransplantation of splenic tissue following splenic trauma, is uncommonly clinically significant. Splenosis is typically diagnosed incidentally on imaging or at laparotomy and has been mistakenly attributed to various malignancies and pathological conditions. On the rare occasion when splenosis plays a causative role in a pathological condition, a diagnostic challenge may ensue that can lead to a delay in both diagnosis and treatment. The following case report describes a patient presenting with a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed resulting from arterial enlargement within the gastric fundus secondary to perigastric splenosis. The cause of the bleeding was initially elusive and this case highlights the importance of a thorough clinical history when faced with a diagnostic challenge. Treatment options, including the successful use of transarterial embolization in this case, are also presented.

Keywords: therapeutic, endoscopy, UGIB, intervention

Introduction

Splenosis refers to the autotransplantation of splenic tissue following a splenectomy or splenic trauma. It is thought to be secondary to the seeding and subsequent growth of splenic cells within the peritoneal cavity and, less commonly, within extraperitoneal locations.1–3 Given that splenosis is usually asymptomatic, its true incidence is unknown.4 The diagnosis of splenosis is usually made incidentally on imaging or at laparotomy, masquerading as benign or malignant tumors or other pathological conditions, such as endometriosis.5 It is uncommonly of clinical significance and despite the extent of neovascularization which occurs as the splenic tissue grows, major bleeding complications are rare.6 The following report describes a rare case of massive gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to perigastric splenosis that was treated successfully with transarterial embolization.

Case

A 52-year-old male with no previous history of gastrointestinal bleeding presented to the emergency department with chest pain and solid food dysphagia. His medical history included atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, and splenectomy at age 14 following a traumatic splenic rupture after being kicked by a horse. Initial cardiac workup was negative and he was discharged home with an outpatient follow-up appointment with gastroenterology.

His medications included dabigatran, diltiazem, irbesartan, montelukast, budesonide/formeterol, fluticasone/salmeterol, and salbutamol.

Outpatient upper endoscopy identified a Schatzki’s ring at the esophageal–gastric junction as well as several small clean-based ulcers at the prepyloric region on a duodenum hiatus hernia. Biopsies were obtained from the gastric mucosa to rule out Helicobacter pylori. He was placed on a proton-pump inhibitor and sent home following the procedure.

Four days later he re-presented to the emergency department with multiple episodes of melena, light-headedness, progressive shortness of breath on exertion, and rapid atrial fibrillation (heart rate ~130 bpm, normotensive). Bloodwork revealed: hemoglobin 112 g/L (baseline ~150 g/L), mean corpuscular volume 83.8 fL, platelets 312×109/L, creatinine 79 μmol/L, urea 10.8 mmol/L, international normalized ratio 1.2, partial thromboplastin time 28, and normal liver function tests. He was given 1 L of crystalloid, placed on a pantoprazole infusion, and his dabigatran was held.

Urgent upper endoscopy revealed stigmata of recent hemorrhage from recent biopsy sites, the previously observed clean-based ulcers, and a submucosal lesion in the third part of the duodenum, which was not bleeding. The biopsy sites were cauterized with a gold-probe and he was admitted for observation.

On post-admit day 2, the patient had a syncopal episode associated with melena and a hemoglobin decline of 30 g/L. Repeat endoscopy revealed only a large adherent clot in the fundus, which could not be aspirated. The patient’s melena persisted and hemoglobin continued to fall prompting another upper endoscopy that demonstrated a small pouch in the gastric fundus without any stigmata of recent hemorrhage, but concerning for either a diverticulum or fistula. A subsequent upper gastrointestinal series confirmed a mild focal out-pouching of the gastric fundus without any evidence of a fistula or leak. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and revealed replacement of the spleen by multiple soft tissue nodules consistent with splenosis, but could not identify a clear source of bleeding due to retained oral contrast within the stomach from the prior upper gastrointestinal series. On post-admit day 8, the patient had a repeat CT scan which revealed a previously unidentified 1.3 cm perigastric lesion with moderate vascularity within the gastric fundus. The possibility of a gastric varix was raised. An endoscopic ultrasound was performed, which did not reveal any large varices, but did confirm a number of smaller perforating vessels within the fundal lesion, as well as several perigastric lesions, which were later identified as perigastric splenosis. Endoscopic ultrasound-assisted fine-needle aspiration of one of the perigastric lesions revealed a mixed population of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils favoring a reactive lymph node, thus, nondiagnostic.

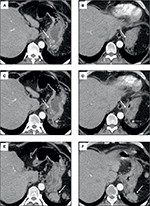

The patient continued to have melena stool and a subsequent CT angiogram was acquired revealing an extensive network of enlarged arteries within the wall of the gastric fundus that were supplying a grouping of splenosis along the posterior aspect of the gastric fundus (Figure 1). The dominant arterial supply was localized to a branch of the left inferior phrenic artery, which underwent successful transarterial coil embolization that was confirmed on a follow-up CT scan (Figures 1 and 2). The patient clinically improved, his hemoglobin stabilized, and he was ultimately discharged home.

Follow-up imaging 2 months later revealed further interval decrease in the size of the intramural gastric arterial collaterals perfusing the perigastric splenules. As of the most recent follow-up appointment 8 months following the patients’ initial presentation, there was no further bleeding. Verbal consent was provided by the patient to have his data used in this study.

Discussion

Splenosis is an acquired condition that can arise following iatrogenic or traumatic splenic rupture. Residual viable splenic tissue can autotransplant throughout the peritoneal cavity and elsewhere, deriving its blood supply from adjacent tissues and organs.5 The splenic implants are commonly found within the greater omentum due to its vascularity, which provides an ideal environment for regeneration and neovascularization. Additional potential sites of implantation include (in order of frequency): the serosal surface of the small bowel, parietal peritoneum, mesentery, diaphragm, intrahepatic, and intrathoracic.6–8 Although splenosis has been implicated in intestinal obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding, and relapse of hematological diseases, patients are usually asymptomatic and the diagnosis is typically made incidentally on imaging or at laparotomy.3 As the ectopic splenic tissue may provide a degree of normal splenic function, asymptomatic splenosis is managed conservatively and resection is unnecessary.3,5,9

Diagnosing splenosis can be challenging given the extent and varied potential sites for autotransplantation as well as its relatively nonspecific appearance on conventional imaging modalities (ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance imaging). As such, splenosis has been mistakenly reported as renal, adrenal, or abdominal tumors, metastases, lymphoma, endometriosis, and ectopic testicles.6 The diagnosis of splenosis can be confirmed by scintigraphy with technetium Tc 99m-labeled red blood cells.10,11 Biopsies taken from the splenic tissue of splenosis generally display characteristics consistent with splenic tissue, such as red and white pulp and marginal zones.5

Gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to splenosis is rare and usually occult.5,6 To our knowledge, three cases of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to splenosis have been reported in the literature. All cases required surgical resection for definitive management (Table 1).3,6,11 This is the first case of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to splenosis involving the gastric fundus successfully managed through endovascular embolization.

Bias

Cognitive errors are common pitfalls in medicine and surgery. In practice, the anchoring heuristic implies relying on initial impressions to answer a clinical question.12 In our case report, the patient initially presented with a massive gastrointestinal bleed shortly following upper endoscopy and gastric biopsy. Despite the rarity of massive bleeding following routine endoscopic gastric biopsy, this became the initial working diagnosis.13 Following an additional episode of bleeding, a repeat upper endoscopy suggested the bleeding to be secondary to a gastric diverticulum, a more common cause than gastric splenosis. The disposition to consider a diagnosis as being more likely after being previously exposed to such a diagnosis defines the availability heuristic.12 As a consequence, arriving at the patient’s true diagnosis was delayed. Finally, a CT scan demonstrated a perigastric vascular lesion, considered at one point to be a potential gastric varix with therapeutic endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate considered, further exemplifying the availability heuristic. Fortunately, the patient’s underlying history was reconsidered and an endoscopic ultrasound performed ruling out gastric varices. Subsequent consultation with an interventional radiologist and acquisition of a triphasic CT scan ultimately uncovered the correct diagnosis and led to successful embolization of an enlarged branch of the left inferior phrenic artery perfusing a grouping or perigastric splenosis.

Interobserver variability may have played a role in delaying the diagnosis of the fundal lesion as well. A study conducted by Lau et al found the level of agreement between experts assessing the severity of bleeding peptic ulcers using video endoscopy was poor in more than a third of occasions.14 In our case report, each endoscopy was performed by a different gastroenterologist. Within large tertiary care facilities, it is unlikely an emergent procedure will be performed by the same interventionist on the same patient. As a result, interobserver variability is a potential source of bias.

Conclusion

Although the pathology was nondiagnostic and scintigraphy with technetium Tc 99m-labeled red blood cells was not performed, given the patient’s course and findings on imaging, a diagnosis of splenosis was made and treated successfully. Thus, we suggest considering splenosis in the main differential diagnoses in patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and a history of prior splenic trauma.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Ludtke FE, Mack SC, Schuff-Werner P, Voth E. Splenic function after splenectomy for trauma. Role of autotransplantation and splenosis. Acta Chir Scand. 1989;155(10):533–539. | ||

Gunes I, Yilmazlar T, Sarikaya I, Akbunar T, Irgil C. Scintigraphic detection of splenosis: superiority of tomographic selective spleen scintigraphy. Clin Radiol. 1994;49(2):115–117. | ||

Basile RM, Morales JM, Zupanec R. Splenosis, a cause of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Surg. 1989;124(9):1087–1089. | ||

Normand JP, Rioux M, Dumont M, Bouchard G. Ultrasonographic features of abdominal ectopic splenic tissue. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1993;44(3):179–184. | ||

Sikov WM, Schiffman FJ, Weaver M, Dyckman J, Shulman R, Torgan P. Splenosis presenting as occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2000;65(1):56–61. | ||

Margari A, Amoruso M, D’Abbicco D, Notarnicola A, Epifania B. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to a splenotic nodule of the gastric wall. Chir Ital. 2008;60(6):863–865. | ||

Brancatelli G, Vilgrain V, Zappa M, Lagalla R. Case 80: Splenosis. Radiology. 2005;234(3):728–732. | ||

Wedemeyer J, Gratz KF, Soudah B, et al. Splenosis – important differential diagnosis in splenectomized patients presenting with abdominal masses of unknown origin. Z Gastroenterol. 2005;43(11):1225–1229. | ||

Balfanz JR, Nesbit ME Jr, Jarvis C, Krivit W. Overwhelming sepsis following splenectomy for trauma. J Pediatr. 1976;88(3):458–460. | ||

Bresciani C, Ferreira N, Perez RO, Jacob CE, Zilberstein B, Cecconello I. Splenosis mimicking gastric GIST: case report and literature review. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2011;24(2):183–185. | ||

Alang N. Splenosis: an unusual cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. R I Med J. 2013;96(11):48–49. | ||

Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):775–780. | ||

Domellöf L, Enander LK, Nilsson F. Bleeding as a complication to endoscopic biopsies from the gastric remnant after ulcer surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18(7):951–954. | ||

Lau JY, Sung JJ, Chan AC, et al. Stigmata of hemorrhage in bleeding peptic ulcers: an interobserver agreement study among international experts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(1):33–36. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.