Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 10

Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases in elderly patients

Authors Yue M, Li S, Yan G, Li C, Kang Z

Received 7 November 2017

Accepted for publication 14 March 2018

Published 10 August 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 2581—2587

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S156379

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Lu-Zhe Sun

Meng Yue, Shiquan Li, Guoqiang Yan, Chenyao Li, Zhenhua Kang

Department of Surgery, First Hospital, JiLin University, Changchun, Jilin, People’s Republic of China

Purpose: This study aimed to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) in elderly patients.

Patients and methods: Between January 2009 and January 2016, LH was performed for 241 consecutive patients who were ≥60 years old and had CRLM. Based on their age at the LH, the patients were divided into an elderly group (≥70 years old, 78 patients) and a middle-aged group (60–69 years old, 163 patients). The short- and long-term outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Results: Compared to the middle-aged group, the elderly group had higher values for Charlson comorbidity index, proportion of preoperative chemotherapy, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score. No other significant differences were observed in the preoperative characteristics. The elderly group had a higher conversion rate, compared to the middle-aged group, although no significant differences were observed in the surgical procedures, surgical times, intraoperative blood losses, numbers and severities of postoperative 90-day complications, postoperative 90-day mortality rates, pathology results, and other short-term outcomes. Long-term follow-up revealed similar rates of recurrence, disease-free survival, and overall survival in the two groups. Multivariable analysis revealed that age did not independently predict overall survival or disease-free survival.

Conclusion: Similar short- and long-term outcomes were observed after LH for CRLM in elderly and middle-aged patients. Thus, advanced age is not a contraindication for LH treatment in this setting.

Keywords: laparoscopic hepatectomy, minimally invasive surgery, colorectal liver metastases, surgical oncology

Introduction

The westernization of Chinese lifestyle has created recent trends toward decreased physical activity, increased life expectancy, and an increased incidence of colorectal cancer.1 Studies have demonstrated that approximately one-half of colorectal cancers develop liver metastases, and surgical resection is the primary treatment for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM).2–4 A large number of studies have revealed that the 5-year overall survival rate is 30%–60% among patients who undergo radical resection for CRLM, and good long-term survival can be achieved using open hepatectomy for CRLM.5–7 However, ~70% of patients with CRLM are ≥65 years old when they seek treatment, and elderly patients may be less able to tolerate hepatectomy (versus younger patients), which has led some surgeons to reject hepatectomy for elderly patients.5–8

The first reported laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) was performed in 1992,9 and a growing number of reports have described LH treatment for CRLM.10–15 Compared to open hepatectomy, LH for CRLM leads to lesser intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, similar or lower incidences of complications, and similar long-term outcomes.10–15 However, the previous studies have not included large numbers of elderly patients, and only a few English reports have described LH treatment for CRLM.16–19 Furthermore, there is a lack of studies comparing short- and long-term outcomes of LH treatment between elderly and middle-aged patients with CRLM. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the short- and long-term outcomes of LH treatment among elderly and middle-aged patients with CRLM.

Patients and methods

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki rules. This retrospective research was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Hospital, JiLin University. The need for informed consent from all patients was waived because this was a retrospective study. All data had no personal identifiers and were kept confidential.

Between January 2009 and January 2016, 241 consecutive patients underwent LH treatment for CRLM and were considered eligible for this retrospective study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) the patient was undergoing their first hepatectomy, 2) the patient had undergone radical resection of colorectal cancer, and 3) complete clinical and follow-up data were available for the patient. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) repeat hepatectomy and 2) palliative hepatectomy. Based on their age at the LH, the patients were divided into an elderly group (≥70 years old, 78 patients) and a middle-aged group (60–69 years old, 163 patients). The location, number, diameter, and operability of liver metastatic lesions were preoperatively confirmed in all patients using tumor biomarkers, abdominal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and other examinations. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography was performed as needed. Lung function tests, electrocardiography, echocardiography, and other examinations were performed to determine the patients’ preoperative cardiopulmonary function. All patients were operated using the totally laparoscopic technique, and intraoperative ultrasonography was performed in all cases. The LH was performed according to a previous report.19 All LHs were carried out by the surgeon Dr Zhenhua Kang. Before this study, he had successfully completed 50 LH surgeries.

The Clavien–Dindo criteria were used to classify the severity of postoperative 90-day complications. Minor complications were defined as grades I–II and major complications as grades III–V. Postoperative 90-day mortality was defined as any death from oncological or non-oncological causes within 90 days after surgery.

After the patients were discharged, follow-ups were performed at outpatient clinics, the patient’s house, community health service centers, and other locations. The follow-ups were performed every 3 months during the first year after surgery, every 4 months during the second year, every 6 months during the third year, and annually thereafter. Patients were referred for in-hospital treatment if tumor recurrence was suspected at any time. The follow-up rate was 100%, as all patients lived near our hospital, and the last follow-up was performed on May 31, 2017.

All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed variables were analyzed by Student’s t-tests and presented as mean and SD. Non-normally distributed variables were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test and presented as medians and ranges. Differences between semiquantitative results were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U tests. Differences between qualitative results were analyzed by chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Survival rates were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between the two groups were analyzed by log-rank test. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to identify the factors predictive of poor disease-free survival and overall survival by using both forward and backward stepwise selection. Explanatory variables with univariate P values ≤0.100 were included in the multivariable analysis. The results are reported as hazard ratios with 95% CIs. A level of 5% was set as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

The patients’ general preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared to the middle-aged group, the elderly group had significantly higher values for Charlson comorbidity index, proportion of preoperative chemotherapy, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists score. No other significant differences were observed in the other preoperative characteristics (e.g., gender, body mass index, TNM stage, pre-LH carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and location of liver metastases).

| Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the two groups Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. |

The patients’ short-term prognoses are shown in Table 2. Both groups underwent similar surgical procedures, with most patients undergoing wedge resection or sectionectomy and a few patients undergoing left lateral sectionectomy. No significant inter-group differences were observed in the surgical times, intraoperative blood losses, intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusion rates, or incidences and severities of postoperative complications. The elderly group had a higher rate of conversion to open hepatectomy, and conversion in both groups was primarily related to bleeding. There were no intraoperative deaths in either group, although one patient in the elderly group died within 90 days because of liver failure and one patient in the middle-aged group died after 2 months because of metastasis to the central nervous system. Both groups had similar pathology results.

| Table 2 Short-term outcomes of the two groups |

The median follow-ups for the elderly and middle-aged groups were 31 and 34 months, respectively, and this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.387). During the follow-ups, 32 patients in the elderly group died because of recurrence (n=29), ischemic stroke (n=1), hemorrhagic stroke (n=1), and sudden cardiac death (n=1), as shown in Table 3. Fifty-three patients in the middle-aged group died because of recurrence (n=48) and non-cancer-related diseases (n=5). There were no significant inter-group differences in the recurrence locations, median time to recurrence, or other factors (Table 3).

| Table 3 The follow-up data of the two groups |

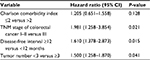

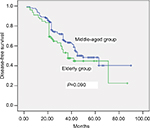

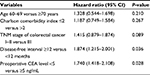

The 5-year overall survival rates for the elderly and middle-aged groups were 52% and 59%, respectively, and this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.139; Figure 1). Multivariable analyses revealed that TNM stage, disease-free interval, and number of metastases independently predicted overall survival (Tables 4 and 5). The 5-year disease-free survival rates for the elderly and middle-aged groups were 45% and 49%, respectively, and this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.090; Figure 2). Multivariable analyses revealed that disease-free interval and preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels independently predicted disease-free survival (Tables 6 and 7). Age did not independently predict overall or disease-free survival.

| Figure 1 Comparison of overall survival rate between elderly and middle-aged groups (P=0.139). |

| Table 4 Univariate Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. |

| Table 5 Cox proportional hazards model for overall survival |

| Figure 2 Comparison of disease-free survival rates between elderly and middle-aged groups (P=0.090). |

| Table 6 Univariate Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease-free survival Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis. |

| Table 7 Cox proportional hazards model for disease-free survival Abbreviation: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis. |

Discussion

Increasing life expectancy is leading to a rise in the surgical treatment of elderly patients with CRLM, and surgical resection of liver metastases is considered safe for these patients. However, elderly individuals have more comorbidities and less cardiopulmonary functional reserve, compared to younger patients, and elderly patients experience relatively high rates of postoperative complications and mortality.5–8 These factors explain the relatively small proportion of elderly patients in the present study, as well as their higher Charlson comorbidity index and American Society of Anesthesiologists score, compared to middle-aged patients. Interestingly, the patients and their families expressed concern regarding the surgery and a desire for non-surgical CRLM treatments.

The liver receives an abundant supply of blood from the hepatic artery and portal vein, and bleeding is common during open hepatectomy.20–23 However, it is difficult to control any bleeding and replicate some of the open procedures during LH, which can necessitate conversion to open hepatectomy in up to 12% of cases.10–15 In the present study, the conversion rate among elderly patients was higher than that among middle-aged patients (7% versus 1%, respectively), and bleeding was the overwhelming reason for conversion to open hepatectomy. These findings may be related to the deterioration of physiological mechanisms (e.g., vascular elasticity) and coagulation function in elderly patients, which makes it difficult to control intraoperative bleeding.24–26 Thus, only open hepatectomy can ensure patient safety. Although we did not detect any obvious differences in the preoperative platelet counts and coagulation test results, coagulation is a very complicated process that may not be completely described using clinical platelet counts and coagulation tests.

The current guidelines categorize LH based on the extent and complexity as minor hepatectomy, major hepatectomy, and difficult hepatectomy.27 Only minor hepatectomy was performed in the present study, and previous reports have also confirmed that LH generally involves minor hepatectomy,5–8 with a few reports showing major and difficult hepatectomy. This is likely because major and difficult hepatectomies are inherently difficult to perform using the open approach, and the laparoscopic approach further complicates the surgery. Thus, patients who require major or difficult hepatectomy for CRLM may not be able to benefit from the advantages of laparoscopic surgery. Nevertheless, recent reports have indicated that laparoscopic major and difficult hepatectomy is safe and feasible,28–31 and our hospital began performing laparoscopic major and difficult hepatectomy in June 2016, based on the accumulated experience with LH. We hope to generate additional data to examine the utility of laparoscopic major and difficult hepatectomy in future studies.

Relatively few elderly patients with CRLM undergo LH because of concerns among surgeons that elderly patients may not be able to tolerate pneumoperitoneum, which can lead to higher intraperitoneal pressure and CO2 retention in the blood. These factors can theoretically lead to cardiopulmonary complications, although none of the elderly patients in the present study experienced severe cardiopulmonary complications. Three elderly patients experienced minor lung infections, based on the Clavien–Dindo criteria,32–35 although they recovered fully after treatment using intravenous antibiotics.

Previous studies have revealed 5-year overall survival rates of 48%–61% and 5-year disease-free survival rates of 43%–58% among elderly patients who underwent hepatectomy for CRLM.36–38 We observed similar outcomes among our elderly patients, and their outcomes were comparable to those of the middle-aged patients. The predominant cause of death among elderly patients was tumor recurrence, with relatively few deaths caused by non-oncological diseases. Therefore, LH appears to be beneficial when indicated for elderly patients with CRLM and to provide good long-term survival, compared to the outcomes for middle-aged patients. Moreover, elderly patients with CRLM have an extremely poor prognosis after receiving non-surgical treatments.

The present study has two important limitations. First, the retrospective design is associated with known risks of bias, and a prospective randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm that LH is safe and effective for elderly patients with CRLM. Second, we only examined data from a single center with a small sample size, and it is possible that our findings may not generalize to other centers and/or patient groups. The fact that the study failed to find statistical significance between the two groups in survival may be due to the small sample size.

Conclusion

The present study results indicate that LH was not associated with elevated rates of postoperative complications or mortality among elderly patients with CRLM, and that their long-term outcomes were comparable to those of middle-aged patients. Therefore, advanced age is not a contraindication for LH treatment of CRLM.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely thank our colleagues who participated in this research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Chen W, Zheng R, Zuo T, Zeng H, Zhang S, He J. National cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2012. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28(1):1–11. | ||

Heinrich S, Lang H. Liver metastases from colorectal cancer: technique of liver resection. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(6):579–584. | ||

Akgül Ö, Çetinkaya E, Ersöz Ş, Tez M. Role of surgery in colorectal cancer liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(20):6113–6122. | ||

McNally SJ, Parks RW. Surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Dig Surg. 2013;30(4–6):337–347. | ||

Matias M, Casa-Nova M, Faria M, et al. Prognostic factors after liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis. Acta Med Port. 2015;28(3):357–369. | ||

Frankel TL, D’Angelica MI. Hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(1):2–7. | ||

Parau A, Todor N, Vlad L. Determinants of survival after liver resection for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J BUON. 2015;20(1):68–77. | ||

Mentha G, Terraz S, Andres A, Toso C, Rubbia-Brandt L, Majno P. Operative management of colorectal liver metastases. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;3(3):262–272. | ||

Reich H, McGlynn F, DeCaprio J, Budin R. Laparoscopic excision of benign liver lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(5 Pt 2):956–958. | ||

Luo L, Zou H, Yao Y, Huang X. Laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: short- and long-term outcomes comparison. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(10):18772–18778. | ||

Jiang X, Liu L, Zhang Q, et al. Laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term outcomes. J BUON. 2016;21(1):135–141. | ||

Emile SH. Evolution and clinical relevance of different staging systems for colorectal cancer. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):43–52. | ||

Wu D, Wu W, Li Y, et al. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases located in all segments of the liver. J BUON. 2017;22(2):437–444. | ||

Sahay SJ, Fazio F, Cetta F, Chouial H, Lykoudis PM, Fusai G. Laparoscopic left lateral hepatectomy for colorectal metastasis is the standard of care. J BUON. 2015;20(4):1048–1053. | ||

Kazaryan AM, Marangos IP, Røsok BI, et al. Laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: surgical and long-term oncologic outcome. Ann Surg. 2010;252(6):1005–1012. | ||

Allard MA, Cunha AS, Gayet B, et al; Colorectal Liver Metastases-French Study Group. Early and long-term oncological outcomes after laparoscopic resection for colorectal liver metastases: a propensity score-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):794–802. | ||

Zeng Y, Tian M. Laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for elderly patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J BUON. 2016;21(5):1146–1152. | ||

Spampinato MG, Arvanitakis M, Puleo F, et al. Totally laparoscopic liver resections for primary and metastatic cancer in the elderly: safety, feasibility and short-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(6):1881–1886. | ||

Nomi T, Fuks D, Kawaguchi Y, Mal F, Nakajima Y, Gayet B. Laparoscopic major hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases in elderly patients: a single-center, case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(6):1368–1375. | ||

Huntington JT, Royall NA, Schmidt CR. Minimizing blood loss during hepatectomy: a literature review. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(2):81–88. | ||

Emile SH. Advances in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: fluorescence-guided surgery. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):53–65. | ||

Emile SH. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: technique, oncologic, and functional outcomes. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(2):74–84. | ||

Xie M, Zhu J, He X, et al. Liver metastasis from colorectal cancer in the elderly: is surgery justified? Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(12):3525–3535. | ||

Chen J, Bai T, Zhang Y, et al. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic and open hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with liver cirrhosis: a systematic review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):20679–20689. | ||

Goussous N, Shmelev A, Cunningham SC. Minimally invasive surgery for gallbladder cancer. Minim Invasive Surg Oncol. 2017;1(3):103–116. | ||

Buell JF, Cherqui D, Geller DA, et al; World Consensus Conference on Laparoscopic Surgery. The international position on laparoscopic liver surgery: the Louisville Statement, 2008. Ann Surg. 2009;250(5):825–830. | ||

Coelho FF, Kruger JA, Fonseca GM, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection: experience based guidelines. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(1):5–26. | ||

Yoon YS, Han HS, Cho JY, Ahn KS. Total laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma located in all segments of the liver. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(7):1630–1637. | ||

Xiang L, Xiao L, Li J, Chen J, Fan Y, Zheng S. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in the posterosuperior liver segments. World J Surg. 2015;39(5):1202–1209. | ||

Xiao L, Xiang LJ, Li JW, Chen J, Fan YD, Zheng SG. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in posterosuperior segments. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(10):2994–3001. | ||

Lee W, Han HS, Yoon YS, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma located in the posterosuperior segments or anterolateral segments: a case-matched analysis. Surgery. 2016;160(5):1219–1226. | ||

Xiao H, Xie P, Zhou K, et al. Clavien-Dindo classification and risk factors of gastrectomy-related complications: an analysis of 1049 patients. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8262–8268. | ||

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–196. | ||

Wang W, Shao M, Zhang R. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopic versus open surgery for elderly patients with rectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(9):18160–18167. | ||

Wu D, Li Y, Yang Z, Feng X, Lv Z, Cai G. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma in elderly patients: a pair-matched study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(2):3465–3472. | ||

Wang C, Luo W, Fu Z, Sun M, Si H, Guo D. A propensity score-matched case-control comparative study of laparoscopic and open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J BUON. 2017;22(4):936–941. | ||

Nagano Y, Nojiri K, Matsuo K, et al. The impact of advanced age on hepatic resection of colorectal liver metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(4):511–516. | ||

Figueras J, Ramos E, López-Ben S, et al. Surgical treatment of liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma in elderly patients. When is it worthwhile? Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9(6):392–400. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.