Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 12

Severe Fatigue is an Important Factor in the Prognosis of Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Sorafenib

Authors Qiu X , Li M, Wu L, Xin Y, Mu S, Li T, Song K

Received 4 October 2019

Accepted for publication 3 August 2020

Published 4 September 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 7983—7992

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S233448

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Ahmet Emre Eşkazan

Xuan Qiu, Manjiang Li, Liqun Wu, Yang Xin, Siyu Mu, Tianxiang Li, Kangjian Song

Liver Disease Center, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Liqun Wu

Liver Disease Center, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, No. 59 Haier Road, Laoshan District, Qingdao, Shandong 266003, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 15315328331

Email [email protected]

Objective: To investigate the effects of fatigue on the survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib.

Patients and Methods: A retrospective analysis of 182 cases of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib in our hospital from October 1, 2008, to October 31, 2017, showed clinical and pathological data and follow-up results. The clinical and pathological data as well as follow-up results of 182 patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib in our hospital from October 1, 2008, to October 31, 2018, were retrospectively analyzed. All patients were treated for at least 3 months. Patients were divided into three groups: fatigue grade I (n=74), fatigue grade II (n=62), and fatigue grade III (n=46), according to National Cancer Institute common terminology criteria for adverse events (NCI CTCAE) version 5.0. Survival analysis between groups was performed by the Kaplan–Meier method (Log rank test), continuous variables were analyzed by t-test, and categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square test.

Results: The overall survival (OS) of patients who were relieved of fatigue was 33.0± 9.3 months, whereas the OS of patients who were not relieved of fatigue was 15.0± 1.8 months (P< 0.000). Furthermore, the time to progress (TTP) of patients who were relieved of fatigue by resting was 20.3 ± 10.9 months compared to a TTP of 7.7 ± 1.0 months in patients who were not relieved of fatigue (P< 0.000).

Conclusion: Patients, especially the elderly and infirm, were more susceptible to toxicity.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, sorafenib, fatigue, survival

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 The number of HCC deaths (approximately 800,000 per year) overlap with that of new cases, a testament to its high lethality.1,2 In recent years, with the advancement of diagnostic techniques and the improvement of surgical methods, the early diagnosis rate and resection rate of HCC have been improved, but even in patients with tumor resection, the recurrence rate after the resection is as high as 68%- 98%, the patient’s long-term prognosis is extremely poor.2

Sorafenib is a molecular targeted therapeutic. It is an oral multi-target, multi-kinase inhibitor that targets the serine/threonine kinase and receptor tyrosine on tumor cells and tumor blood vessels.3–5 Two Phase III clinical trials of Sorafenib, Sharp and Oriental, and Gideon have shown that sorafenib shows therapeutic effects in patients with advanced liver cancer and inoperable patients, and can improve the time to disease progression in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and Overall survival time.6,7

Common adverse reactions to sorafenib include diarrhea, rash, scaling, fatigue, skin reactions in the hands and feet, hair loss, nausea, vomiting, itching, high blood pressure and loss of appetite. Fatigue is the most common symptom associated with cancer and cancer treatment. It is a subjective symptom, but objectively, under the same conditions, it will lose more or less its normal activities or work ability.8,9 This condition has a negative impact on the functional status of the cancer patient and the health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which affects many aspects of daily simple physical activity.8,10,11 Fatigue is a multifactorial process, and the precise underlying pathophysiology is still often unclear; therefore, many interventions for the treatment of this condition remain empirical.11–13 Among the underlying causes, anemia and hypothyroidism play an important role, accompanied by comorbidities such as cachexia. The onset of moderate or severe fatigue may have a serious impact on treatment, and the need to reduce the dose until the symptoms subsided may affect the outcome of patients treated with sorafenib.11 Fatigue is usually associated with many endocrine disorders. In cancer patients treated with VEGFR TKI, the overlap of signs and symptoms caused by treatment and the tumor itself makes it difficult to identify and manage endocrine-related dysfunction associated with fatigue development. These factors include changes in the adrenal gland, thyroid gland, and gonads, as are bone and glucose metabolism abnormalities.14,15 Fatigue is one of the most common side effects, and it can also lead to the adjustment of sorafenib dosage or even the interruption of treatment.

Fatigue is one of the common adverse reactions to sorafenib, but few have been reported in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. This study investigated the adverse effects and prognosis of 182 patients taking sorafenib from October 1, 2008, to October 31, 2018, to investigate the effect of sorafenib on the prognosis of such patients.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The clinical data and follow-up results of 182 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University from October 1, 2008, to October 31, 2018, were retrospectively analyzed. There were 163 males and 19 females with an average age of 56.03 ± 9.8 years. Clinical data included gender, age, previous treatment (resection, ablation, TACE, others), and adverse reactions (hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea, fatigue), drug dose adjustment, hepatitis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, alcoholism, diabetes, Child-Pugh classification, TNM staging, survival time, and disease progression time. All patients were diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma by postoperative pathology or CT/MR. Solid tumor evaluations were performed in all patients using mRECIST.15

Inclusion criteria: 1. Hepatocellular carcinoma was confirmed by imaging or surgical resection; 2. Sorafenib was administered for more than 3 months.

Exclusion criteria: 1. Patient with Child-Pugh grade C; 2. Patients with an ECOG PS score of ≥3 before medication.

Sorafenib administration

The initial dose of sorafenib was 800 mg/day in two divided doses. Adverse reactions (AE) to administration of sorafenib were recorded, and the criteria for fatigue were based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (NCI-CTCAE v4.0). Adverse reactions were examined on the 10th day and one month after drug administration. When there was an adverse reaction of grade III or above, the dose was adjusted to 400mg/day (one oral dose per day) or temporarily discontinue, and the withdrawal time should not exceed 7 days.16

Follow-Up

Patients administered sorafenib were followed up once a month, all in the clinic. Liver function and AFP were reviewed monthly; CT was reviewed once every 3 months, and enhanced CT, enhanced MRI or related examinations (such as radionuclide bone scan or PET-CT) were performed when disease progression was suspected. Time to disease progression was calculated by referencing the date of imaging diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

Univariate analysis was used to identify predictors of survival using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons were performed using the Log rank test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

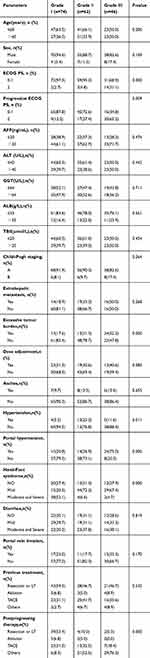

The study included 163 male patients and 19 female patients. Baseline data are shown in Table 1. Their average age was 56.01 years (range: 35–81 years). The patients included 147 cases of viral hepatitis B and 3 cases of viral hepatitis C. Premedication: 93 patients with liver transplantation or hepatectomy, 64 patients with TACE, 13 patients with ablation, and 12 patients with direct oral medication. There were 162 cases of Child-Pugh grade A and 20 cases of Child-Pugh grade B. ECOG PS 0–1163 cases (89.6%), ECOG PS score 0–1 was 126 (69.2%) in patients 1 month after taking the drug.

|

Table 1 Baseline Data |

The survival factors of the patients in this group were analyzed and obtained in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Factors Influencing Survival After Taking Sorafenib |

According to the multivariate analysis results in Table 2, fatigue is an independent risk factor for HCC patients taking.

Survival Analysis

The OS and TTP analysis of the patients in this group were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method, and Figure 1 is obtained. As can be seen from Figure 1, the median OS for this group of patients was 19.5 months (95% Cl: 16.48–22.53), and the median TTP was 10.7 months (95% Cl: 9.14–12.26) (Table 2). Fatigue is an independent risk factor for the survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib (P<0.009).

|

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier curves of OS (A) and TTP (B) of patients with sorafenib treatment. MST, median survival time; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. |

Fatigue

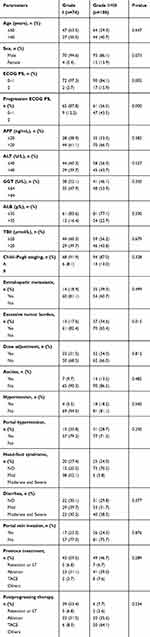

To better study the effects of fatigue on this group of patients, we divided patients into fatigue grade I (n=74), fatigue grade II (n=62), and fatigue grade III (n=46) according to NCI CTCAE version 5.0.17 (Table 3). The following statistics were performed on the baseline data of the grouped patients, as shown in Table 4.

|

Table 3 Tired Rating (NCI CTCAE 5.0) |

|

Table 4 Relationship Between Severity of Fatigue and Clinical and Follow-Up Results [n(%)] |

After the patients were divided into three groups according to the fatigue level, the overall survival time (OS) and time to disease progression (TTP) analysis of the patients after grouping were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method, and Figure 2 is obtained.

|

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival curves associated with OS (A), TTP (B) and fatigue in patients treated with sorafenib. |

OS and TTP

The median follow-up time of the overall survival for patients with grade I, II, and III fatigue was 33.0 months, 18.3 months, and 10.1 months (P<0.000), with OS time for grade I and II patients. Statistically significant (χ2 = 25.069; P<0.000). The OS time of grade I and III patients was statistically significant (χ2 = 59.272; P<0.000), and the OS time of grade II and III patients was also statistically significant (χ2 =10.667; P=0.001). In the time course of disease progression, the median follow-up time for patients with grade I, II, and III fatigue was 20.3, 10.0, and 6.2 months (P<0.000), with grade I and grade II patients. The TTP was statistically significant (χ2 = 21.606; P<0.000). The TTP of patients with grade I and III fatigue was statistically significant (χ2 = 39.931; P<0.000). The TTP of patients with grade II and III fatigue was also statistically significant (χ2 = 5.861; P = 0.015).

Patients with grade II and III fatigue were combined and compared with those with grade I fatigue, and the results are presented in Figures 3 and 4.

|

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival curves of patients taking sorafenib until time to OS and fatigue. |

|

Figure 4 Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival curves of patients taking sorafenib until TTP and fatigue. |

The results indicated that fatigue that can be relieved by resting had an important effect on the overall survival time of patients and on time to disease progression. We analyzed the patients after regrouping and the results are shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Baseline Table for Grade I and Grade II+III |

Discussion

Sorafenib is a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits tumor proliferation and angiogenesis.3,7,18,19 The formulation has mild to moderate toxicity and a variety of solid tumors are resistant to it.7,20 This is the first systemic drug that has been shown to prolong the survival of liver cancer patients in two phase III trials.6,7,20 It is now the standard for systemic treatment in patients with advanced liver cancer.13,21–24 To prolong the survival of patients with advanced liver cancer, the initial dose of sorafenib recommended in the treatment is 800 mg/day. However, since the incorporation of sorafenib into clinical applications, and because of the intolerable side effects, a lower initial dose has been reported, with starting dose of 800 mg/day that decreases to 400 mg/day, or a starting dose of 400 mg/day. A large number of reports have reported side effects in patients such as hand-foot reactions as well as the effects of drug dosage on patient survival due to intolerable side effects.17,23,25 There have been few reports of patients suffering from fatigue due to sorafenib. This article explores and elaborates these issues.

At present, it is believed that the fatigue experienced by patients with liver cancer is mainly due to the weak constitution of the patient, the dyscrasia caused by the tumor, the side effects caused by the drug itself, the tumor burden26 and the psychological state of the patient, but the exact mechanism of its occurrence is still not clear.12 Fatigue is one of the common adverse reactions to sorafenib. Therefore, studies on the drug-related fatigue would have a greater impact on the survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.27,28 Drug-related fatigue is different from tumor-related fatigue. The so-called tumor-related fatigue refers to the continuous subjective fatigue caused by the treatment for the tumor or the tumor itself. It has nothing to do with the daily activities of the patient. Furthermore, tumor-related fatigue affects the patient’s activities and their restfulness. During post-remission therapy; drug-related fatigue is caused by the side effects of the drug, and changes the dosage of the drug can improve fatigue. Here, our team analyzed 182 patients from our hospital. The fatigue was related to tumor burden and physical fitness, and most patients could adjust the dose to reduce fatigue.

In clinical practice, treatment-related fatigue is a painful and disabling disease that is often underreported, misled and under-managed.10–13,20 Studies have shown that fatigue was the most common side effect, leading to a dose reduction or even treatment interruption.3,4 Patients, especially the elderly and infirm, are more susceptible to the drug’s toxicity, and studies have shown that they may be associated with more comorbidities or poor nutrition.1,19,22 An analysis of the patient’s fatigue-related indicators can guide a customized treatment plan for the patient and reduce the risk of fatigue-related dose reduction or treatment interruption. Therefore, the determination of risk factors for fatigue may allow for early management in the most susceptible patients. At the same time, the new and simpler classification method in this paper is more conducive to clinical practice.

After regrouping the patients, the patients were analyzed by chi-square test. The ECOG PS of the two groups were different before or after treatment with the drug. The patients with severe fatigue had larger tumor burdens, while the patients with less fatigue had better hand-foot reactions. The above results are in line with the current mainstream views.9,17,23,24

In this study, patients taking sorafenib had TTP time (MST) of 10.7months (95% Cl: 9.3––12.1) and a total OS time (MST) of 19.0months (95% Cl: 15.5––22.5). In this clinical trial review, the prognosis of patients with hand-foot reaction was better; but the prognosis of patients with vascular invasion was poor, which was consistent with previous literature reports. After grouping the patients according to their fatigue level, Kaplan–Meier (Log rank test) was performed, followed by Cox analysis. The median OS times of patients with grades I, II, III fatigue were 20.9, 18.7 and 13.0 months, respectively. This indicated that the lighter the fatigue, the longer the overall survival time. Furthermore, of all patients, 158 (90.8%) patients a preoperative ECOG score ≤1, whereas 19 (83.1%) patients had an ECOG score of ≤1 after taking sorafenib. Overall, the patient’s fatigue was related to the administration of sorafenib. Good physical foundation is conducive to resistance to fatigue, so as to obtain a longer survival period.

According to the survival curve analysis and whether the patients can be grouped according to the fatigue of rest relief, the OS of the patients who were relieved of fatigue was 33.0±9.3 months, whereas the OS of the patients who could not be relieved of fatigue was 15.0±1.8 months. This difference was statistically significant. (P<0.000).Furthermore, the TTP of patients who were relieved of fatigue by rest was 20.9 months (95% Cl: 18.3–27.8), compared a TTP of 7.7months (95% Cl: 8.8–12.2) in patients who were not relieved of fatigue. This difference was also significantly different (P<0.000). Overall, fatigue relieved by rest is an important factor that affects the OS of patients.

Conclusion

Based on a study of 182 patients, treatment-related fatigue is an independent risk factor affecting the TTP and OS of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The new and simpler classification method in this paper is more conducive to clinical practice.

Furthermore, approximately 59.3% of patients were unable to reduce their fatigue through rest, fatigue can seriously affect the prognosis of patients.

Ethics Approval and Consent

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All patients signed a written informed consent. The study was conducted in strict compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (ethics approval number: QYFYEC 2013-021-01). All the participants and the contributors of this work have signed informed consent for publication.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Shandong Province, People’s Republic of China.

Author Contributions

Xuan Qiu and Liqun Wu collected patients’ data. Xuan Qiu analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Xuan Qiu and Liqun Wu conducted this study and revised the manuscript. All authors took part in the treatment of patients. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.18

2. Cabrera R, Nelson DR. Review article: the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(4):461–476.

3. Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, et al. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(10):835–844. doi:10.1038/nrd2130

4. Gordon SW, McGuire WP, Shafer DA, et al. Phase I study of sorafenib and vorinostat in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42(8):649–654. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000567

5. Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66(24):11851–11858. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377

6. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

7. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7

8. Curt GA. The impact of fatigue on patients with cancer: overview of FATIGUE 1 and 2. Oncologist. 2000;5:9–12. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-suppl_2-9

9. Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the fatigue coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5:353–360. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353

10. Poort H, Jacobs JM, Pirl WF, et al. Fatigue in patients on oral targeted or chemotherapy for cancer and associations with anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Palliat Support Care. 2019;19:1–7.

11. Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, et al. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):22–34. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22

12. Santoni M, Conti A, Massari F, et al. Treatment-related fatigue with sorafenib, sunitinib and pazopanib in patients with advanced solid tumors: an up-to-date review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(1):1–10. doi:10.1002/ijc.28715

13. Lodish MB, Stratakis CA. Endocrine side effects of broad-acting kinase inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(3):R233–44. doi:10.1677/ERC-10-0082

14. Brassard M, Neraud B, Trabado S, et al. Endocrine effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor vandetanib in patients treated for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):2741–2749. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2771

15. Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1247132

16. Fu Y, Wei X, Li L, Xu W, Liang J. Adverse reactions of sorafenib, sunitinib, and imatinib in treating digestive system tumors. Thorac Cancer. 2018;9(5):542–547. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.12608

17. Ogawa C, Morita M, Omura A, et al. Hand-foot syndrome and post-progression treatment are the good predictors of better survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib: a multicenter study. Oncology. 2017;93(Suppl 1):113–119. doi:10.1159/000481241

18. Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(5):965–972. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124

19. Van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1879–1886. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5

20. Alves RC, Alves D, Guz B, et al. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Review of targeted molecular drugs. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10(1):21–27. doi:10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31582-0

21. Keating GM. Sorafenib: a review in hepatocellular carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2017;12(2):243–253. doi:10.1007/s11523-017-0484-7

22. Saraswat VA, Pandey G, Shetty S. Treatment algorithms for managing hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(Suppl 3):S80–9. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.05.004

23. Vincenzi B, Santini D, Russo A, et al. Early skin toxicity as a predictive factor for tumor control in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Oncologist. 2010;15(1):85–92. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0143

24. Otsuka T, Eguchi Y, Kawazoe S, et al. Skin toxicities and survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2012;42(9):879–886. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.00991.x

25. De Giorgi U, Scarpi E, Sacco C, et al. Standard vs adapted sunitinib regimen in elderly patients with metastatic renal cell cancer: results from a large retrospective analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(3):182–189. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2013.11.005

26. Wang YY, Zhong JH, Xu HF, et al. A modified staging of early and intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma based on single tumour >7 cm and multiple tumours beyond up-to-seven criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(2):202–210. doi:10.1111/apt.15074

27. Rimassa L, Danesi R, Pressiani T, Merle P. Management of adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: improving outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;77:20–28. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.05.004

28. Ochi M, Kamoshida T, Ohkawara A, et al. Multikinase inhibitor-associated hand-foot skin reaction as a predictor of outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(28):3155–3162. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i28.3155

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.