Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

Self-reported quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: preliminary results based on the Polish MS Registry

Authors Brola W , Sobolewski P , Fudala M , Flaga S , Jantarski K, Ryglewicz D, Potemkowski A

Received 30 March 2016

Accepted for publication 14 June 2016

Published 26 August 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 1647—1656

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S109520

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Waldemar Brola,1 Piotr Sobolewski,2 Małgorzata Fudala,1 Stanisław Flaga,3 Konrad Jantarski,4 Danuta Ryglewicz,5 Andrzej Potemkowski6

1Department of Neurology, Specialist Hospital, Końskie, 2Department of Neurology, Holy Spirit Specialist Hospital, Sandomierz, 3AGH University of Science and Technology, Krakow, 4Swietokrzyski Regional Branch of the Polish National Health Fund (NFZ), Kielce, 5First Department of Neurology, Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw, 6Department of Psychology, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland

Background: The aim of the study was to analyze selected clinical and sociodemographic factors and their effects on the quality of life (QoL) of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients registered in the Polish MS Registry.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional observational study performed in Poland. Data on personal and disease-specific factors were collected between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2015, via the web portal of the Polish MS Registry. All patients were assessed by a physician and asked to complete the Polish language versions of the following self-evaluation questionnaires: EuroQol 5-Dimensions, EuroQoL Visual Analog Scale, and Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale. Univariate analysis and logistic regression were performed to determine the factors associated with QoL.

Results: The study included 2,385 patients (female/male ratio 2.3:1) with clinically confirmed MS (mean age 37.8±9.2 years). Average EuroQol 5-Dimensions index was 0.72±0.24, and the mean EuroQoL Visual Analog Scale score was 64.2±22.8. The average Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale score was 84.6±11.2 (62.2±18.4 for physical condition and 23.8±7.2 for mental condition). Lower QoL scores were significantly associated with higher level of disability (odds ratio [OR], 0.932; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.876–0.984; P=0.001), age >40 years (OR, 1.042; 95% CI, 0.924–1.158; P=0.012), longer disease duration (OR, 0.482; 95% CI, 0.224–0.998; P=0.042), and lack of disease modifying therapies (OR, 0.024; 95% CI, 0.160–0.835; P=0.024). No significant associations were found between QoL, sex, type of MS course, patient’s education, and marital status.

Conclusion: The Polish MS Registry is the first national registry for long-term observation that allows for self-evaluation of the QoL. QoL of Polish patients with MS is significantly lower compared with the rest of the population. The parameter is mainly affected by the level of disability, duration of the disease, and limited access to immunomodulatory therapy.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, Poland

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive, inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system and represents one of the major causes of neurological disability in young people.1 The estimated prevalence of MS in Europe over the past three decades is 83 cases per 100,000 people, with higher rates in northern countries, and the mean annual incidence is 4.3 per 100,000 people.2,3 The number of MS patients worldwide exceeds 2.3 million of whom approximately 600,000 live in Europe.1–3 It is estimated that there are 40,000–50,000 such patients in Poland, while the prevalence of MS is estimated to be between 37 and 91 cases per 100,000 citizens.4 In Poland, no epidemiological studies or systematic studies of quality of life (QoL) that include the overall population of the country have been conducted.5 Most published studies from Poland were performed many years ago and provided data pertaining to only 10% of Poland’s area.6–14 Systematic registration of patients started in 2011 with the creation of an electronic database called the Polish MS Registry (RejSM).15 All departments and wards of neurology, rehabilitation centers, clinics, and private neurological offices were invited to participate. Registration began in central regions of Poland and was expanded throughout the country. Demographic and clinical data were collected. As investigating QoL is recommended for the assessment of disease progression, treatment effectiveness, and quality of care provided, each patient was asked to independently assess QoL using selected questionnaires, standardized for the Polish population that was available in Polish. The aim of this study was to estimate the effect of the disease on the self-assessed QoL and analyze the demographic and clinical parameters of patients with MS based on information gathered from the RejSM.

Methods

The survey was conducted in several dozen neurological centers in Poland, dealing with the treatment of MS.

Study design

All relevant data were gathered via the web portal of the Rejestr Chorych na Stwardnienie Rozsiane ([Registry of Multiple Sclerosis Patients] RejSM) (http://www.rejsm.pl). Patients with MS were prospectively and retrospectively registered and followed at each visit, in accordance with the McDonald criteria (2010).16 The collected data included patients’ age, sex, family status, place of residence, education, family history, and information directly related to the disease itself, such as the date of onset, type of first symptoms, date of diagnosis, type of disease, comorbidities, occurrence of relapses, additional examinations and tests (magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, evoked potentials), Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) results, and types of treatment (modifying the course of the disease and symptomatic treatment). Data were recorded by an experienced neurologist. All participating centers took responsibility for their data and accepted source data monitoring. MS specialists responsible for data collection had been previously trained in data collection, patient monitoring, and treatment procedures. The patients were evaluated with the EDSS proposed by Kurtzke.17 Questionnaires were completed by assessing the QoL: EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) and EuroQol Visual Analog Scale (EQ-VAS)18 and Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29).19 Patients completed the questionnaires either during a meeting with a doctor or later at home, by registering at the web portal.

The EQ-5D questionnaire consists of two parts: the EQ-5D descriptive system and EQ-VAS.18 The EQ-5D descriptive system covers the following five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each of the dimensions has three levels: 1= no problem, 2= some problems, and 3= severe problems. Respondents indicate their state of health by ticking the box next to the most appropriate statement for each of the five dimensions. The combination of one level from each dimension defines the individual’s state of health.

The answers provided by each respondent were presented as a five-digit number describing the respondent’s health state (from “11111” meaning “no problems at all” to “33333” meaning “extreme problems” in all five dimensions). The system defines 243 possible states of health. Each state of health was assigned a certain value (index or weight). In order to calculate EQ-5D-3L index values, we used a Polish EQ-5D-3L value set elicited directly by using the time trade-off method.20,21 These index values illustrate societal preferences for different health states and range from −0.523 to 1.0, where negative values correspond to bad health states (states worse than death) and 1.0 corresponds to perfect health.

EQ-VAS is a standard scale for recording an individual’s rating of their current state of health. The ends of the scale are defined as the “best imaginable health state =100” and the “worst imaginable health state =0”. A Polish version of the EQ-5D is available, and it is standardized for the general Polish population.20,21

MSIS-29 is a disease-specific health-related QoL (HRQoL) instrument, developed using patients’ perspective on disease impact.19 It consists of 29 questions divided into two subscales assessing the physical (MSIS-29-PHYS) and psychological (MSIS-29-PSYCH) impact of MS, of twenty and nine questions, respectively. The responses are recorded on a Likert scale (1–5) and summed up to give a maximum of 100 on MSIS-29-PHYS and 45 on MSIS-29-PSYCH.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or the next of kin before any interview or neurological examination was conducted. All individual data were automatically anonymized by replacing personal identity numbers (Powszechny Elektroniczny System Ewidencji Ludności; Universal Electronic System for Registration of the Population) with unique number codes for use in the study. The study was approved by the Regional Medical Ethics Committee of the Swietokrzyskie Medical Council in Kielce.

Statistical analysis

In the first step, all continuous variables were tested for normal distribution and equality of variances. Mean values of EQ5D index, EQ VAS, MSIS-29-PHYS, and MSIS-29-PSYH were compared in each subgroups using Student’s t-test. The magnitude and clinical relevance of the scores were evaluated by the effect size statistic. According to Cohen’s benchmarks, a value of 0–0.20 denotes negligible, 0.21–0.5 a small, 0.51–0.80 a medium, and >0.80 a large effect size. Logistic regression was done to determine the factors associated with QoL. The results of logistic regression models are presented as odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATISTICA software, version 8.0 (2007; StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

By the end of 2015, the RejSM comprised a list of 4,650 persons with MS, among whom 2,385 independently evaluated their QoL. This group included 1,663 (69.7%) women and 772 (30.3%) men (female/male ratio 2.3:1) with MS, whose diagnoses had been clinically confirmed in accordance with McDonald criteria (2010). The clinical characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 Clinical characteristics of study patientsa |

Patients’ mean age was 37.8±9.2 years, and the average duration of the disease was 14.5±8.5 years. First onset of symptoms most frequently occurred at an age of 29 years. Average time between the onset of first symptoms to final diagnosis amounted to 2.4±1.6 years.

The average degree of disability on EDSS was 3.2±2.1. Relapsing-remitting MS was diagnosed in 68.9% of patients, secondary progressive MS in 21.7%, and primary progressive MS in 9.4%. Diagnosis was made based on neurological examination carried out in all patients and magnetic resonance imaging which was performed in vast majority of patients (98%). Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid was performed in 58.1% of patients, and visual evoked potentials were studied in 71.0%.

At the time of questionnaire completion, 34% were receiving disease modifying therapies (interferon-β, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, or fingolimod), 3.8% of subjects had been treated this way in the past, and 62.2% of patients had never been treated this way. Symptomatic treatment was administered for 98% of patients (72%, spasticity-reducing medications; 42%, antidepressants; 32%, analgesics).

Sociodemographic data according to sex are presented in Table 2. Approximately 49.8% of patients were married, and 50.2% had made a deliberate choice not to get married or were single for other reasons (widowed, divorced, or separated). Female patients with MS either gave birth to one child (57.8%) or did not have children at all (29.2%). Approximately 9.7% of women had two children and very few women had three or more children (3.3%). Among 2,385 people, only 796 (33.5%) were gainfully employed. The source of support for all other subjects was benefits, pensions, or help from their family members. Positive family history defined as presence of MS in parents, siblings, or cousins was observed in 65 (3.9%) women and 32 (4.4%) men.

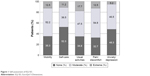

Average EQ-5D index was 0.72±0.24, and the mean score in EQ-VAS was 64.2±22.8. A significant score reduction was observed with reference to age and disease duration. Results of self-evaluation of health based on EQ-5D showed that two-thirds of patients had problems with moving around and performing everyday activities, two-thirds suffered from pain or discomfort and ~50% of patients had problems with self-care or suffered from anxiety or depression (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Self-assessment of EQ-5D. |

The results of this study showed significant associations and the effect sizes with 0.64–1.14 Cohen’s value between age (P<0.001), disability (P<0.001), disease modifying treatment (P<0.001), disease duration (P<0.001), and QoL. A significant relationship between occupational status (P=0.013), place of residence (P=0.023), and QoL was also observed, while no significant associations were found between QoL, sex, type of MS course, patient’s education, and marital status.

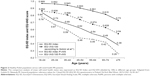

These results affected EQ-VAS-based QoL to a similar extent (Table 3). The comparison of EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores of MS patients with reference values for the Polish population in particular age groups proposed by Golicki et al20,21 is presented in Figure 2.

| Figure 2 Healthy Polish population versus self-rated health MS patients. |

Average MSIS-29 score for the Polish population of patients with MS was 82.5±24.6 (62.2±18.4 for physical condition and 23.8±7.2 for mental condition). In both the physical and psychological components of the MSIS-29 assessment, a significantly lower QoL was declared by dwellers of rural areas, unemployed subjects, subjects with long disease duration, with higher level of disability, and those not treated with disease modifying therapies (DMTs). However, no associations were observed for the results with respect to sex, course of the disease, education, and family status (Table 4).

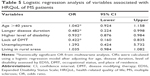

ORs were calculated using a logistic regression model after adjusting for age, disease duration, level of disability assessed by EDSS, DMT, occupational status, and place of residence (Table 5). HRQoL was significantly associated with higher level of disability (OR, 0.932; 95% CI, 0.876–0.984; P=0.001), age >40 years (OR, 1.042; 95% CI, 0.924–1.158; P=0.012), longer disease duration (OR, 0.482; 95% CI, 0.224–0.998; P=0.042), and lack of DMT (OR, 0.024; 95% CI, 0.160–0.835; P=0.024).

Discussion

HRQoL is a broad multidimensional concept that usually includes self-reported measures of physical and mental health. QoL refers to an individual’s overall well-being and daily functioning and can be divided into three principal components: physical health, for example, daily functioning, symptoms such as spasticity, physical disability; mental health, for example, mood, self-esteem, perception of well-being, perceived stigma; and social health, for example, social activities and relationships.

For several dozens of years, HRQoL has been widely used in the evaluation of many chronic diseases. The first study involving HRQoL in MS was published in 1990, and the first comparative study appeared 2 years later.22 Evaluation of the QoL of MS patients has become one of the most crucial elements of the diagnostic process, and minimization of the negative effects of MS on everyday functioning is a significant aim of treatment. In Poland, several attempts have been made to evaluate QoL in small groups of patients with MS, but those analyses were carried out only provisionally, for specific purposes.23–28

Our study is based on the RejSM that encompasses the entire country and is envisaged to continue for many years. The current analysis is an initial assessment of the first registered patients who self-evaluated their QoL using Polish EQ-5D and MSIS-29 questionnaires. Validation of instruments for QoL evaluation with regard to the cultural conditions of a given country is extremely important for interpretation and comparison of results with those obtained in countries with geographic or cultural differences.

One example that illustrates variation between countries is the study carried out in Germany, Austria, and Poland using the same questionnaire (Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis, FAMS), comparing QoL of MS patients in these three countries.29 Country-specific cultural factors significantly affected the results; therefore, is it unreliable to directly compare the effect of MS on the QoL without considering these factors.29 It seems that the QoL of Polish patients with MS is definitely lower compared with countries of Western Europe. This is affected by numerous specific factors, from limited access to treatment, lack of certified MS training health professionals, lack of specialist clinics, to limited access to work for the disabled, their low socioeconomic status, and lack of palliative care. Also, perception of the disease and disability in Polish reality differs from the one in Western countries of Europe. Patients frequently have to fight for their rights on their own. This results from faulty systemic solutions in Polish health care system and wrong approach to disability that is generally expressed by the general population.

EQ-5D was the first QoL questionnaire validated for the Polish population. The validation study was conducted by Golicki et al20,21 in 2008 and 2014 in a representative population for age and sex within the general group of respondents. The mean value of the EQ-5D index was 0.893±0.21, and the EQ-VAS was 73.7±14.4. The most frequently reported complaints were pain/discomfort (45.8%) followed by anxiety/depression (33.3%), while the least commonly reported problem was self-care (9.4%). The use of the EuroQol questionnaire allows for a direct comparison of mean results obtained from MS patients age-matched with the general population (Figure 2). This comparison clearly shows the reduction in QoL of MS patients relative to the healthy Polish population (EQ-5D index 0.72±0.24 and EQ-VAS 64.2±22.8).

The QoL of our MS patients was significantly lower in all age groups with a clear tendency toward a decrease in mean results of EQ-5D and EQ-VAS with age. This most probably resulted from an increase of disability over the course of the disease and appearance of new MS symptoms or onset of other age-related comorbidities. In our study, moderate problems in at least one of the domains were reported by 47% of the respondents, while severe problems were reported by 11.8%. Pain or discomfort was reported by 67.3% of the respondents, daily activity by 65.2%, problems with mobility by 64.7%, anxiety and depression by 51.7%, and self-care by 47.7% of respondents.

In another Polish study involving over 3,500 patients, conducted by Mitosek-Szewczyk et al,30 the mean EQ-5D score was 0.8±0.27, and mean EQ-VAS score was 65.6±21.5. In this group, patients most commonly complained of pain or discomfort (40%), anxiety and depression (38%), and problems with mobility (16%).

The aim of the study was to generally assess the QoL of MS patients, and it did not take into account the effect of particular sociodemographic or clinical factors. This was a one-time undertaking, carried out in 21 selected centers in Poland between May 2008 and January 2009. It involved ~18% of all Polish patients. However, some regions of Poland were not included at all. Our study is a long-term observation, involving patients from all regions of Poland. In addition to EQ-5D, we also applied the MSIS-29. Disease duration in our study was significantly longer (14.5 vs 10.3 years), the disability level in EDSS was lower (3.2 vs 3.6), and treatment involved more patients (34% vs 24%).

In the study by Pierzchała et al31 involving 640 patients from Górny Śląsk, mean EQ-VAS score was 66.11±20.12. Another questionnaire, MSIS-29, standardized for the Polish population,23 also showed a significant effect of MS on the QoL of our patients. As shown in our study and by other authors,32–39 QoL of patients with MS depends on numerous factors and clinical parameters such as the level of disability, disease duration, patient’s age, professional status, and application of appropriate immunomodulatory therapy. The studies differed methodologically and used different questionnaires in culturally disparate populations, preventing accurate comparison. However, the fact that MS is a chronic, incurable disease, inevitably reducing QoL, is certain, which was documented in our study. This was also confirmed in other countries previously.34–39 Older subjects, subjects with progressive, long-term disease, subjects with less-efficient locomotor functions, and those not treated with DMTs evaluate their QoL at a much lower level compared with younger patients with lower EDSS and those treated with DMTs. It seems that QoL is mainly affected by the level of disability, assessed in EDSS, and disease duration. Regardless of the method of QoL evaluation applied, these relations are confirmed by most authors.26–33

The study by Twork et al,40 performed using the MSQOL-54 questionnaire in Germany, indicated that QoL significantly decreases along with the deterioration of motor skills. A rapid decrease of QoL with increasing motor disability occurs up to EDSS 6.5 (severe disability) and then a further gradual reduction of QoL in patients with EDSS >7.0 is evident.

Studies conducted by Patti et al41 indicate that patients in Italy whose EDSS is <3.0 have significantly better scores in all 36-item short form (SF-36) subscales compared with other subjects. In a study of 526 patients from 12 countries with EDSS <7.0, Baumstarck et al42 showed a correlation between a deterioration in the level of motor function and a decrease in QoL. However, these correlations only pertain to areas associated with physical functioning evaluated with both the generic SF-36 and the specific Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) questionnaires.

Disease duration is another significant factor decreasing the QoL, which is confirmed in most publications.38–44 Among Polish authors, only Jamroz-Wiśniewska et al,23 in her study of 104 randomly selected patients (77 women and 27 men; mean age 36.9±9.4 years, mean disease duration 9.05±6.68 years) with diagnosed MS showed no correlation between the QoL in particular aspects of life and disease duration. The authors attributed this result to heterogeneity of the course of MS or occurrence of the mild type of the disease.

Another factor decreasing QoL in Polish patients is poor access to DMT. In Poland, there are very strict therapeutic programs that provide treatment for a narrow scope (EDSS ≤4.5), and in some regions of the country, DMTs are not available at all.

In our study, 34% of all patients were treated with DMT. This is a much higher percentage than the one quoted in MS Barometer 2013,45 which stated that in Poland only 11% of all MS patients are treated with DMT. However, this does not change the fact that Poland is in one of the last places in Europe with respect to access to this therapy. Therapeutic programs are only used by patients with the relapsing-remitting form of MS and moderate disability. They are not available in cases of clinically isolated syndrome and are limited with respect to duration (fingolimod and natalizumab – only 60 months). In many regions of Poland, patients have to wait in queues before they can be treated. The registration process of new medications and their inclusion in reimbursement programs take a very long time, which makes therapeutic personalization impossible.

In our study, significantly lower EQ-5D and MSIS-29 scores were also characteristic for nonworking patients. Only 33.5% of our patients were in gainful employment. It was observed that patients with MS resign or retire earlier or face difficulties with finding a job that would be appropriate for their level of disability. General MSIS-29 evaluation, as well as MSIS-29-PHYS and MSIS-29-PSYCH subscales, confirmed significantly lower QoL in patients living in villages. This factor is rarely mentioned, but in Poland it may be of great significance. Limited access to physicians, awareness, or access to therapies available in large centers can decrease QoL in patients living in rural areas.46

Country dwellers also have significantly limited access to rehabilitation, follow-up examinations, psychologists, and other consultants (ophthalmologists, urologists, and psychiatrists). Due to high unemployment rate, the chances that they will get employed are low, even though their disability may be very mild. Lower level of education, no awareness of health care, and lack of social support are other factors that decrease QoL in Polish patients from rural areas, compared with those living in rural areas in Western countries or inhabitants of larger Polish cities.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. The oldest and most disabled patients may not have been identified. Additionally, some young patients suffering from mild forms of MS might have avoided or not required any contact with the health service during 2011–2015. However, systematic implementation of the registry over the course of the next several years should allow us to identify the entire population of MS patients. It is necessary to continue research aimed at the assessment of other aspects as well, such as the economic status, social support, or access to rehabilitation.

Conclusion

This study comprised ~5% of the population of Polish patients with MS. Long-term observation and further development of the RejSM will provide access to the entire population of MS patients and help comprehensively analyze the factors affecting the quality of their lives. Self-evaluation indicated a significant reduction of QoL compared to the overall population, and it was decreased mainly according to the level of disability, disease duration, and lack of access to immunomodulatory therapy.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank all patients, collaborators, and institutions that contributed to this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1502–1517. | ||

Pugliatti M, Rosati G, Carton H, et al. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(7):700–722. | ||

Kingwell E, Marriott JJ, Jette N, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Europe: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2013;13(128):1–13. | ||

Potemkowski A. Multiple sclerosis in Poland and worldwide – epidemiological considerations. Aktualn Neurol. 2009;9(2):91–97. | ||

Brola W, Fudala M, Flaga S, Ryglewicz D. Need for creating Polish registry of multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2013;47(5):484–492. | ||

Cendrowski W. Multiple sclerosis in a small urban community in central Poland. J Neurol Sci. 1965;2(1):82–86. | ||

Cendrowski W, Wender M, Dominik W, Flejsierowicz Z, Owsianowski M, Popiel M. Epidemiological study of multiple sclerosis in western Poland. Eur Neurol. 1969;2(2):90–108. | ||

Wender M, Pruchnik-Grabowska D, Hertmanowska H, et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Western Poland – a comparison between prevalence rates in 1965 and 1981. Acta Neurol Scand. 1985;72(2):210–217. | ||

Kowal P, Wender M, Pruchnik-Grabowska D, Hertmanowska H. Contribution to the epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Poland. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1986;7(2):201–204. | ||

Wender M, Kowal P, Pruchnik-Grabowska D, et al. Multiple sclerosis: its prevalence and incidence in the population of western Poland. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 1987;21(1):33–39. | ||

Fryze W, Obiedziński R. Występowanie stwardnienia rozsianego wśród mieszkańców miasta Tczew położonego na północy Polski. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 1996;(Suppl 3):77. | ||

Potemkowski A. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in the region of Szczecin: prevalence and incidence 1993–1995. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 1999;33(3):575–585. | ||

Potemkowski A. An epidemiological survey of a focus of multiple sclerosis in the province of Szczecin. Przegl Epidemiol. 2001;55:331–341. | ||

Łobińska A, Stelmasiak Z. Epidemiological aspects of multiple sclerosis in Lublin (Poland). Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2004;38(5):361–366. | ||

Brola W, Fudala M, Flaga S, Ryglewicz D, Potemkowski A. Polish registry of multiple sclerosis – current status, perspectives and problems. Aktualn Neurol. 2015;15:68–73. | ||

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292–302. | ||

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurological impairment in multiple sclerosis and expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–1452. | ||

Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. | ||

Hobart JC, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29); a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 5):962–973. | ||

Golicki D, Niewada M, Jakubczyk M, Wrona W, Hermanowski T. Self-assessed Heath status in Poland: EQ-5D findings from the Polish valuation study. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010;120(7–8):276–281. | ||

Golicki D, Niewada M. General population reference values for 3-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire in Poland. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2015;125(1–2):18–26. | ||

Rudick RA, Miller D, Clough JD, Gragg LA, Farmer RG. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(12):1237–1242. | ||

Jamroz-Wiśniewska A, Papuć E, Bartosik-Psujek H, Belniak E, Mitosek-Szewczyk K, Stelmasiak Z. Validation of selected aspects of psychometry of the Polish version of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale 29 (MSIS-29). Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2007;41(3):215–222. | ||

Opara JA, Jaracz K, Brola W. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Med Life. 2010;3(4):352–358. | ||

Kułakowska A, Bartosik-Psujek H, Hożejowski R, Mitosek-Szewczyk K, Drozdowski W, Stelmasiak Z. Selected aspects of the epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Poland – a multicentre pilot study. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2010;44(5):443–452. | ||

Karakiewicz B, Stala C, Grochans E, et al. Assessment of the impact of some sociodemographic factors on the quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2010;56(3):107–112. | ||

Papuć E, Stelmasiak Z. Factors predicting quality of life in a group of Polish subjects with multiple sclerosis: accounting for functional state, socio-demographic and clinical factors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(4):341–346. | ||

Łabuz-Roszak B, Kubicka-Baczyk K, Pierzchała K, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis – association with clinical features, fatigue and depressive syndrome. Psychiatr Pol. 2013;47(3):433–442. | ||

Pluta-Fuerst A, Petrovic K, Berger T, et al. Patient reported quality of life in multiple sclerosis differs between cultures and countries: a cross-sectional Austrian-German-Polish study. Mult Scler. 2011;17(4):478–486. | ||

Mitosek-Szewczyk K, Kułakowska A, Bartosik-Psujek H, Hożejowski R, Drozdowski W, Stelmasiak Z. Quality of life in Polish patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Med Sci. 2014;59(1):34–38. | ||

Pierzchała K, Adamczyk-Sowa M, Dobrakowski P, Kubicka-Baczyk K, Niedziela N, Sowa P. Demographic characteristics of MS patients in Poland’s upper Silesia region. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125(5):344–351. | ||

Papuć E, Stelmasiak Z. Factors predicting quality of life in a group of Polish subjects with multiple sclerosis: accounting for functional state, socio-demographic and clinical factors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(4):341–346. | ||

Wilski M, Tasiemski T, Kocur P. Demographic, socioeconomic and clinical correlates of self-management in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(21):1970–1975. | ||

Isaksson AK, Ahlstrøm G, Gunnarsson LG. Quality of life and impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:64–69. | ||

Findling O, Baltisberger M, Jung S, Kamm CP, Mattle HP, Sellner J. Variables related to working capability among Swiss patients with multiple sclerosis – a cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0121856. | ||

Phillips GA, Wyrwich KW, Guo S, et al. Responder definition of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale physical impact subscale for patients with physical worsening. Mult Scler. 2014;20(13):1753–1760. | ||

Jones KH, Ford DV, Jones PA, et al. The physical and psychological impact of multiple sclerosis using the MSIS-29 via the web portal of the UK MS Register. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55422. | ||

Jones KH, Ford DV, Jones PA, et al. How people with multiple sclerosis rate their quality of life: an EQ-5D survey via the UK MS register. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65640. | ||

Gupta S, Goren A, Phillips AL, Dangond F, Stewart M. Self-reported severity among patients with multiple sclerosis in the U.S. and its association with health outcomes. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(1):78–88. | ||

Twork S, Wiesmeth S, Spindler M, et al. Disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: non-linearity of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:55. | ||

Patti F, Russo P, Pappalardo A, et al. Predictors of quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis: an Italian cross-sectional study. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252(2):121–129. | ||

Baumstarck K, Pelletier J, Butzkueven H, et al. Health-related quality of life as an independent predictor of long-term disability for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(6):907–914. | ||

Yamout B, Issa Z, Herlopian A, et al. Predictors of quality of life among multiple sclerosis patients: a comprehensive analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(5):756–764. | ||

Kwiatkowski A, Marissal JP, Pouyfaucon M, Vermersch P, Hautecoeur P, Dervaux B. Social participation in patients with multiple sclerosis: correlations between disability and economic burden. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:115. | ||

European Multiple Sclerosis Platform. MS Barometer 2013. Available from: http://www.emsp.org/projects/ms-barometer/. Accessed January 22, 2016. | ||

Opara J, Jaracz K, Brola W. Burden and quality of life in caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2012;46(5):472–479. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.