Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 11

Safety and efficacy of duloxetine in Japanese patients with chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: an open-label, long-term, Phase III extension study

Authors Uchio Y, Enomoto H , Ishida M , Tsuji T , Ochiai T, Konno S

Received 17 April 2018

Accepted for publication 7 June 2018

Published 31 July 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 1391—1403

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S171395

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

Yuji Uchio,1 Hiroyuki Enomoto,2 Mitsuhiro Ishida,3 Toshinaga Tsuji,4 Toshimitsu Ochiai,5 Shinichi Konno6

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Shimane University School of Medicine, Shimane, Japan; 2Bio-medicine, Medicines Development Unit, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Kobe, Japan; 3Clinical Research Development, Shionogi & Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan; 4Medical Affairs Department, Shionogi & Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan; 5Biostatistics Center, Shionogi & Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan; 6Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan

Purpose: To assess long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of duloxetine in Japanese patients with chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis.

Methods: In this open-label extension study (NCT02335346), Japanese patients with knee osteoarthritis and pain (Brief Pain Inventory [BPI] – Severity average pain score ≥4 at start of randomized trial) who had previously received duloxetine 60 mg/day or placebo for 14 weeks in a double-blind randomized trial entered the extension and received duloxetine 60 mg/day for 48 weeks. The primary outcome was safety/tolerability, secondary outcomes were change in BPI-Severity (BPI-S) average pain, BPI-Interference (BPI-I), Patient Global Impression-Improvement (PGI-I), Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I), 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF36), and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), and exploratory outcomes were knee range of motion (efficacy outcome) and Kellgren–Lawrence grade (safety outcome).

Results: Of 323 patients who completed the randomized trial, 93 (50 placebo, 43 duloxetine) entered the extension. Most patients (85, 91.4%) experienced an adverse event, most commonly constipation, nasopharyngitis, somnolence, and dry mouth (≥10% of patients). There were eight serious adverse events in seven patients and no deaths. No obvious duloxetine-related changes were observed in laboratory tests, vital signs, or electrocardiograms. The change from baseline in BPI-S average pain score was significant throughout the extension. Significant reductions in BPI-I, PGI-I, CGI-I, WOMAC, and SF36 scores were also maintained through 52 weeks. There were no substantial changes in range of motion or Kellgren–Lawrence grade.

Conclusion: In Japanese patients with chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis, long-term treatment with duloxetine was well tolerated and associated with sustained improvements in pain and health-related quality of life without radiographic deterioration.

Keywords: analgesics, chronic pain due to knee osteoarthritis, duloxetine, quality of life, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is an increasingly common degenerative joint disease, with the worldwide age-standardized prevalence of OA increasing by 32.9% between 2005 and 2015.1 The prevalence of symptomatic (ie, with pain or stiffness) OA of the knee increases with age and obesity and is more common in women than in men.2 In nonobese adults in the USA, the prevalence of symptomatic knee OA ranges from 0.74% (men aged 25–34 years) to 14.97% (women aged ≥85 years).3 The lifetime risk of developing symptomatic knee OA in the USA has been estimated to range from 13.83%3 to 44.7%.4 OA has substantial negative effects on morbidity and socioeconomic perspectives and is often associated with pain, functional impairment, and loss of quality of life (QoL),5 as well as reduced work productivity and high medical costs to patients.5–7

The Research on Osteoarthritis/osteoporosis Against Disability (ROAD) study has investigated the characteristics of Japanese patients with knee OA.8–10 In this prospective cohort study, the overall prevalence of radiographic knee OA in Japanese people aged 40 years and older was 17.9% (21.5% in women and 11.6% in men).8 The results led the authors to estimate that >25 million Japanese people aged 40 years and older may have radiographic knee OA.10 Knee pain was a common symptom in the ROAD study, observed in approximately half the patients with radiographic knee OA, with a prevalence of 5.0% in men and 11.3% in women aged 40 years and older.8 Among people aged 60 years and older, the risk of knee pain increases with the severity of OA (according to Kellgren–Lawrence [KL] grade).9 As expected, QoL is adversely affected by knee pain and associated with KL grade.8 Pharmacotherapy is one type of intervention that can reduce pain and improve QoL in patients with knee pain due to OA. In Japan, the currently available pharmacotherapy options include systemic and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, intraarticular hyaluronic acid, intraarticular steroids, and weak opioids. As knee OA is a chronic disease and its prevalence associated with aging, physicians need to assess the risk–benefit balance of pain medication prescribed to patients, primarily from the perspective of safety.

Duloxetine is a serotonin and noradrenaline-reuptake inhibitor that is approved in the USA as analgesia for chronic musculoskeletal pain, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathic pain, and in Japan for chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, diabetic neuropathic pain, and chronic pain due to OA. The recent Japanese approval of duloxetine for OA pain was supported in part by the results of a Phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Japanese patients with chronic OA associated with knee pain.11 In this trial, 14 weeks of treatment with duloxetine (60 mg/day) significantly reduced pain intensity and improved health-related QoL (HRQoL). However, as knee OA and its associated pain are chronic conditions, it is important to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of duloxetine in the treatment of knee OA, which has not been previously reported. Here, we report the results of an open-label, 52-week extension of the randomized trial, which assessed the long-term safety and efficacy of duloxetine 60 mg/day in Japanese patients with knee pain due to OA.

Methods

This study was conducted at 28 medical institutions throughout Japan between January 2015 and March 2016. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each study site (Table S1) and conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study design and treatment protocol

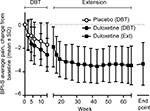

This was a multicenter, long-term, open-label, extension study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02335346) of a previously conducted randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial of duloxetine in Japanese patients with chronic knee pain due to OA (NCT02248480). As described previously,11 patients in the double-blind trial were randomized (using an interactive Internet-response system and stochastic minimization) 1:1 to placebo or duloxetine (Cymbalta; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) taken orally once daily after breakfast (Figure 1A). The dose of duloxetine was increased from 20 mg/day (1 week) to 40 mg/day (1 week) to the target dose of 60 mg/day (12 weeks). At the end of the 14-week treatment phase, patients entered a 1-week dose-tapering phase. After completing the 1-week dose-tapering phase, patients were invited to participate in this extension study (Figure 1A). There was no washout period before entering the extension. Duloxetine was increased to 60 mg/day over 2 weeks. Patients then received duloxetine 60 mg/day for 48 weeks. After completion of treatment in the extension study (or discontinuation), patients underwent tapering for 2 weeks, followed by an observational phase of 1 week. The use of analgesic medication was not restricted during the extension study. Other allowed and prohibited treatments/interventions were similar to those in the previous study.11

| Figure 1 (A) Study design and (B) patient disposition. Abbreviation: Dlx, duloxetine. |

Study population

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the double-blind trial have been described previously.11 The main inclusion criteria were male and female outpatients aged 40–79 years with current OA based on American College of Rheumatology classification of idiopathic OA of the knee,12 pain for ≥14 days of each month for the previous 3 months, and Brief Pain Inventory-Severity (BPI-S) 24-hour average pain score ≥4. A validated Japanese version of the BPI was used.13 Patients were excluded from this study if they had serious medical or neuropsychiatric disorders, clinically significant laboratory abnormalities, or electrocardiographic abnormalities; alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase concentration ≥100 IU/L or total bilirubin ≥1.6 mg/dL; serum creatinine concentration ≥2 mg/dL, renal transplantation, or renal dialysis; diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune disorder, uncorrected thyroid disease, uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, history of uncontrolled seizures, or uncontrolled or poorly controlled hypertension; depression diagnosed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview;14 invasive procedures (eg, proximal tibial osteotomy, total knee arthroplasty); suicidal ideation or attempt; or a primary painful condition that could interfere with assessment of the knee. Excluded medications were monoamine oxidase inhibitor treatment within 14 days and analgesic agents (other than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen) or other medication used for treatment of chronic pain.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of the extension study was the safety and tolerability of duloxetine, assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), severity of AEs, and rate of discontinuation due to an AE. AEs included those that continued from the double-blind phase and those that occurred after the start of the extension study. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 17.1 was used to code and summarize all AEs. Standard laboratory measures, vital signs, body weight, and electrocardiography were also assessed.

The efficacy of duloxetine for pain reduction was assessed by the BPI-S 24-hour average pain score, which uses a scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).13 Global improvement from baseline (start of the double-blind phase) was assessed by using the Patient Global Impression-Improvement (PGI-I)15 and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scales,16 recorded by patients and physicians, respectively, and rated from 1 (very much better) to 7 (very much worse).

HRQoL was assessed by patient-reported BPI-Interference (BPI-I) with seven daily activities (general activities, walking ability, normal work, mood, enjoyment of life, relationships with people, and sleep), rated from 0 (does not interfere) to 10 (completely interferes);13 the Short-Form Health Survey (SF36), consisting of 36 questions related to the patient’s health status within eight subscales (physical functioning, physical role limitations, emotional role limitations, general health perceptions, social functioning, bodily pain, vitality, and mental health) and rated from 0 to 100;17 and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), consisting of 24 questions pertaining to the patient’s knee condition on three subscales (pain, stiffness, and physical function), each on a 5-point (0–4) scale, with lower scores indicating better knee condition.18 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-II, consisting of 21 items related to symptoms of depression on a 4-point (0–3) scale,19 was also assessed. Range of motion (ROM) of the knee, an exploratory efficacy measure, was measured by goniometry. The KL grade, an exploratory safety measure, was evaluated in one knee by examination of radiography in the upright position.

Statistical analysis

A target sample size of 90 patients was set for this extension study to allow for 60 patients treated with duloxetine for 1 year, assuming an estimated maximum withdrawal rate of 30%. The safety analysis population included all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. The efficacy analysis population included all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study treatment and had at least one BPI-S average pain-score measurement after the start of treatment. Missing data were not imputed, and a last observation carried forward approach was used for end-point values. Baseline was defined as the start of the double-blind phase. All safety and efficacy measurements are summarized descriptively. Baseline characteristics and ROM data are presented as number (%), mean (SD), and/or median (range), safety data presented as number (%), and efficacy data presented as mean value or mean change from baseline, with 95% CI or SD.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Of 323 patients who completed the 14-week, double-blind study, a total of 93 patients (50 placebo, 43 duloxetine 60 mg) entered the extension study (Figure 1B). Of these, 81 (87.1%) completed the 52-week extension. The main reason for discontinuation from the extension study was an AE. The rate of discontinuation due to an AE was greater in patients from the placebo group of the double-blind phase (7 of 50, 14.0%) than in patients from the duloxetine group (4 of 43, 9.3%). The baseline characteristics of patients who entered the extension study were similar to those of the overall study population in the double-blind phase of the study (Table S2). Most (72%) patients were female, with a mean age of 66.2 years, mean OA duration of 4.8 years, and mean BPI-S average pain score of 4.9.

Safety and tolerability

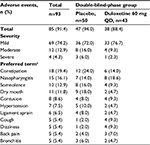

Almost all (91.4%) patients reported an AE during the extension study (Table 1). The most common AEs (reported by ≥10% of patients) were constipation, nasopharyngitis, somnolence, and dry mouth, consistent with the incidence of these AEs during the double-blind phase among patients receiving duloxetine.11 The incidence of AEs, especially constipation, somnolence, and dry mouth, was greater in patients who received placebo during the double-blind phase than in those who received duloxetine. Most patients experienced a mild (69 of 93, 74.2%) or moderate (12 of 93, 12.9%) AE, and four (4.3%) patients had a severe AE (all were SAEs).

| Table 1 Adverse events occurring during the extension study (≥5% in total) Notes: aMedical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 17.1. Abbreviation: QD, quaque die (once daily). |

There was a total of eight SAEs in seven patients (7.5% of patients) during the extension study: six of these patients had received placebo during the double-blind phase. One patient developed infectious enteritis (not considered related to the study drug) and loss of consciousness after a fall the next day (considered possibly related to the study drug). The other SAEs were intervertebral disk protrusion (two patients), progressive supranuclear palsy, lumbar spinal stenosis, femur fracture, and intestinal obstruction (one patient each). All SAEs led to discontinuation from the study, except for one case of intervertebral disk protrusion. All SAEs were considered resolved or recovered by the end of the study, except for the progressive supranuclear palsy. No obvious changes attributable to duloxetine were observed in laboratory tests, vital signs, or electrocardiography findings.

Efficacy and health-related QoL outcomes

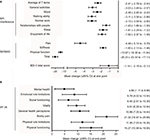

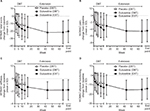

As reported previously,11 during the double-blind phase the mean BPI-S average pain score decreased to a greater extent in duloxetine-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients (Figure 2). Importantly, mean BPI-S average pain score decreased further during the extension study, including in patients who had previously received duloxetine, and was maintained throughout the 52-week extension study. The change from baseline (before starting continuous, long-term administration of the study drug, ie, at the start of the double-blind phase) in BPI-S average pain score was significant (upper 95% CI was negative) at all time points during the extension study. Duloxetine treatment was associated with significant improvements from baseline in pain, stiffness, and physical function, as assessed by WOMAC scores (Figures 3A and S1), and these improvements were maintained during the extension study (Figure S1). Both PGI-I and CGI-I scores also improved during the extension study (Figure S2).

Comprehensive measures of HRQoL (BPI-I, SF36) significantly improved from the start of the double-blind phase to the end of the extension study (Figure 3). There were significant improvements in all BPI-I and SF36 profiles. The largest improvements occurred for items related to physical aspects of HRQoL, such as BPI-I general activities, walking ability, and normal work, and SF36 bodily pain, physical functioning, and physical role limitations. Further, items related to mental, emotional, and social aspects also improved significantly. There was also a small but significant improvement in BDI-II scores from the start of the double-blind phase to the end of the extension study.

Exploratory analysis

Long-term treatment with duloxetine was not associated with any major changes in the ROM efficacy measure (Table 2) or the KL-grade safety measure (Table 3). A change in KL grade from baseline to the end of the extension study was observed in only seven patients, all of whom had received placebo during the double-blind phase (Table 3). KL grade worsened from KL1 or KL2 to KL3 in three patients and improved from KL3 to KL2 in four patients.

| Table 2 Changes in range of motion from baseline to the end of the extension study Abbreviation: QD, quaque die (once daily). |

| Table 3 Changes in KL grade from baseline to last observation Abbreviations: KL, Kellgren–Lawrence; QD, quaque die (once daily). |

Discussion

This is the first long-term study of duloxetine in the treatment of chronic knee pain due to OA. In this extension study of a randomized placebo-controlled trial conducted in Japanese patients with knee OA,11 duloxetine was generally well tolerated, and there were no additional safety concerns with use for up to 65 weeks. Duloxetine treatment was associated with significant and sustained improvements in pain, stiffness, and physical function in terms of BPI-S average pain and WOMAC profiles. Importantly, there were also improvements in physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of HRQoL (BPI-I and SF36 scores). These improvements in pain and HRQoL occurred without changes in the severity of OA, as assessed by KL grade. Studies of whether duloxetine is an effective alternative to other analgesics in the long-term treatment of knee pain due to OA are warranted. Long-term administration of analgesics is sometimes necessary in patients with knee OA, especially while they await surgical procedures.

The most common AEs observed in this extension study (constipation, nasopharyngitis, somnolence, and dry mouth) were also observed in the duloxetine group of the prior double-blind study.11 In the double-blind study, constipation, somnolence, and dry mouth, as well as nausea, decreased appetite, and malaise, occurred in >5% of duloxetine-treated patients, and at significantly higher incidence than in placebo-treated patients, and are thus considered duloxetine-related AEs.11 These duloxetine-related AEs were also observed in another 13-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Chinese patients with knee or hip pain due to OA who were treated with 60 mg duloxetine once daily.20 In addition to constipation, somnolence, and dry mouth, other common (>5%) duloxetine-related AEs in the Chinese study included nausea, dizziness, decreased appetite, and insomnia.20 Somnolence and/or constipation were also common duloxetine-related AEs in two other randomized placebo-controlled trials conducted in North American and European patients with knee OA treated with 60–120 mg duloxetine once daily.21,22 Other duloxetine-related AEs in these trials included nausea, fatigue, dizziness, hyperhidrosis, and decreased libido.21,22

Similar incidence rates and types of AEs have also been observed in long-term studies of duloxetine in other chronic pain conditions,23–26 including in Japanese patients.27,28 In a 52-week extension study of duloxetine 60 mg in Japanese patients with fibromyalgia, the most common AEs considered treatment-related were somnolence (22.8%), constipation (18.1%), nausea (14.8%), weight increase (9.4%), dry mouth (7.4%), and malaise (5.4%).27 Most of these AEs occurred during the first 8 weeks of treatment. Similarly, in a 52-week extension study of duloxetine (40 mg or 60 mg) in Japanese patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP), the most common duloxetine-related AEs were somnolence (13.6%), nausea (10.5%), dizziness (7.0%), malaise (4.3%), and vomiting (7.4%). Increases in laboratory aspartate aminotransferase (9.7%) and white blood cell count (8.1%) were also observed.28 In two 52-week extension studies in American and European patients with DPNP,25,26 there were no AEs that occurred at a greater frequency in patients receiving duloxetine 120 mg than in those receiving routine care, except for asthenia in one study (5.6% of duloxetine-treated patients vs no routine care-treated patients, P=0.018).26 Overall, these results suggest that most duloxetine-related AEs are transient and that long-term duloxetine treatment (up to ~1 year) is not associated with any additional safety concerns.

In the current study, long-term treatment with duloxetine was associated with significant and sustained improvements in pain, stiffness, and physical function. Significant improvements were observed in the primary pain measure – BPI-S average pain score – during the extension study. Similar reductions in BPI-S average pain score have been reported in long-term studies of patients with fibromyalgia27 and DPNP28 in Japan, as well as in patients with fibromyalgia23 and chronic low back pain24 in predominantly Western countries. The SF36 bodily pain score was significantly improved by duloxetine treatment in this extension study as well as in previous studies of chronic pain.25–27 Improvements in all three WOMAC subscales (pain, stiffness, and physical function) were also observed in this extension study. The WOMAC index, a patient-reported, disease-specific outcome measure for OA, has been used in several short-term, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine in OA. In these trials, duloxetine was associated with a significantly greater change from baseline in WOMAC total and/or physical function subscales compared with placebo.21,22,29 Our study is the first to report changes in WOMAC scores with long-term duloxetine treatment.

In addition to pain reduction, the primary goals of OA treatment include improvements in function, activities of daily living, and HRQoL.30 In this study, long-term duloxetine treatment was associated with significant improvements in physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of HRQoL, as reported by both patients and physicians. Scores for all BPI-I and SF36 subscales, as well as for PGI-I and CGI-I, were significantly improved and maintained over the course of long-term duloxetine treatment. Improvements in these and other HRQoL measures have been reported in other long-term studies of duloxetine for chronic pain.23–28 These results suggest that reduction of pain and the associated increase in physical functioning resulting from duloxetine treatment can lead to better overall QoL, including mental, emotional, and social aspects.

Long-term treatment with duloxetine was not associated with substantial changes in ROM or KL grade. To our knowledge, this and the prior double-blind trial are the first studies to examine these parameters in patients with knee OA treated with oral pharmacotherapy, although changes in ROM have been studied previously in patients treated with intraarticular therapies, such as corticosteroids.31 The lack of ROM improvement in this study suggests that pain reduction may not be sufficient to increase joint mobility, and that additional therapy, such as exercise therapy, is required in conjunction with analgesia. Although an increase in daily activities made possible by pain reduction could potentially exacerbate knee OA, the lack of KL-grade worsening indicates that long-term treatment with duloxetine was not associated with worsening severity or progression of knee OA from a structural perspective. Further, despite being associated with radiographic progression of knee OA,32–34 KL grade changes slowly over time (compared with other joint disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis) and differences may not be detectable, even after 52 weeks of treatment.

The strengths of this study include its extended duration (52 weeks) and the broad range of outcomes, including safety, efficacy (BPI-S average pain, WOMAC, PGI-I, CGI-I), and comprehensive measures of HRQoL (BPI-I, SF36), as well as the exploratory outcomes of KL grade and ROM. However, the study is limited by its open-label, single-treatment-arm design, the use of a single dose of duloxetine (60 mg), and the inclusion of only Japanese patients. Also, results from clinical trials are not always indicative of real-world results, as patients vary in their characteristics, levels of adherence, and comorbidities that may affect their response to duloxetine. For example, patients with depression were excluded from this study to observe the direct analgesic effects of duloxetine, rather than any potential pain reduction due to improvement in depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, long-term treatment with duloxetine was well tolerated in Japanese patients with knee OA and associated with sustained improvements in pain and comprehensive general and disease-specific HRQoL without any radiographic deterioration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all clinical investigators and patients for their participation in the study. Medical writing assistance was provided by Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP and Hiroko Ebina, BPharm, Ph, MBA of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group – and was funded by Shionogi & Co. Ltd. and Eli Lilly Japan K.K. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3). This study was conducted by Shionogi and funded by Eli Lilly Japan and Shionogi, manufacturers and licensees of Cymbalta (duloxetine) in Japan.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of study results, drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. YU, MI, TO, and SK were involved in the study design and were investigators in the study. TT was an investigator in the study. TO was involved in the data collection and conducted the statistical analysis.

Disclosure

YU received honoraria/consulting fees, travel support, fees for participation in review activities, fees for writing assistance, medicine, equipment, administrative support, and/or grants from Shionogi, Astellas Pharma, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical, Seikagaku, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma, Pfizer Japan, Japan Tissue Engineering, Ayumi Pharmaceutical, Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical, Hoya Technosurgical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Olympus Terumo Biomaterials, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan Sports Medicine Foundation, and the Terumo Foundation for Life Sciences and Arts. HE is an employee of Eli Lilly Japan. MI, TT, and TO are employees of and minor stock holders in Shionogi. SK has received grants, honoraria, reviewing fees, payment for lectures, fees for writing assistance, medicines, equipment, and/or administrative support from Shionogi, MSD, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Eli Lilly Japan, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Showa Yakuhin Kako, Johnson and Johnson, Daiichi Sankyo, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Terumo, Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical, Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Ayumi Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Nippon Shinyaku, Stryker Japan, Tsumura, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

References

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. | ||

Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105(1):185–199. | ||

Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(5):703–711. | ||

Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1207–1213. | ||

Kingsbury SR, Gross HJ, Isherwood G, Conaghan PG. Osteoarthritis in Europe: impact on health status, work productivity and use of pharmacotherapies in five European countries. Rheumatology. 2014;53(5):937–947. | ||

Agaliotis M, Mackey MG, Jan S, Fransen M. Burden of reduced work productivity among people with chronic knee pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(9):651–659. | ||

Hermans J, Koopmanschap MA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Productivity costs and medical costs among working patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(6):853–861. | ||

Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, et al. Association of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis with health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort study in Japan: the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(9):1227–1234. | ||

Muraki S, Oka H, Akune T, et al. Prevalence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and its association with knee pain in the elderly of Japanese population-based cohorts: the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(9):1137–1143. | ||

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, lumbar spondylosis, and osteoporosis in Japanese men and women: the research on osteoarthritis/osteoporosis against disability study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2009;27(5):620–628. | ||

Uchio Y, Enomoto H, Alev L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of duloxetine in Japanese patients with knee pain due to osteoarthritis. J Pain Res. 2018;11:809–821. | ||

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. | ||

Uki J, Mendoza T, Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Takeda F. A brief cancer pain assessment tool in Japanese: the utility of the Japanese Brief Pain Inventory – BPI-J. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16(6):364–373. | ||

Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224–231. | ||

Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. | ||

Busner J, Targum SD. The Clinical Global Impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28–37. | ||

Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1037–1044. | ||

Hashimoto H, Hanyu T, Sledge CB, Lingard EA. Validation of a Japanese patient-derived outcome scale for assessing total knee arthroplasty: comparison with Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC). J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(3):288–293. | ||

Kojima M, Furukawa TA, Takahashi H, Kawai M, Nagaya T, Tokudome S. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2002;110(3):291–299. | ||

Wang G, Bi L, Li X, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in Chinese patients with chronic pain due to osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(6):832–838. | ||

Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, Liu-Seifert H, et al. Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2009;146(3):253–260. | ||

Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract. 2011;11(1):33–41. | ||

Chappell AS, Littlejohn G, Kajdasz DK, Scheinberg M, d’Souza DN, Moldofsky H. A 1-year safety and efficacy study of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(5):365–375. | ||

Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Chappell AS, Walker DJ, Murray I, Backonja M. Maintenance of effect of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain: a 41-week uncontrolled, dose-blinded study. Pain Med. 2010;11(5):648–657. | ||

Wernicke JF, Raskin J, Rosen A, et al. Duloxetine in the long-term management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: an open-label, 52-week extension of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2006;67(5):283–304. | ||

Wernicke JF, Wang F, Pritchett YL, et al. An open-label 52-week clinical extension comparing duloxetine with routine care in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2007;8(6):503–513. | ||

Murakami M, Osada K, Ichibayashi H, et al. An open-label, long-term, phase III extension trial of duloxetine in Japanese patients with fibromyalgia. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(4):688–695. | ||

Yasuda H, Hotta N, Kasuga M, et al. Efficacy and safety of 40mg or 60mg duloxetine in Japanese adults with diabetic neuropathic pain: results from a randomized, 52-week, open-label study. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7(1):100–108. | ||

Frakes EP, Risser RC, Ball TD, Hochberg MC, Wohlreich MM. Duloxetine added to oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for treatment of knee pain due to osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(12):2361–2372. | ||

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–1155. | ||

Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005328. | ||

Emrani PS, Katz JN, Kessler CL, et al. Joint space narrowing and Kellgren-Lawrence progression in knee osteoarthritis: an analytic literature synthesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(8):873–882. | ||

Fukui N, Yamane S, Ishida S, et al. Relationship between radiographic changes and symptoms or physical examination findings in subjects with symptomatic medial knee osteoarthritis: a three-year prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:269. | ||

Nishimura A, Hasegawa M, Kato K, Yamada T, Uchida A, Sudo A. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee among Japanese. Int Orthop. 2011;35(6):839–843. |

Supplementary material

| Table S1 Institutional review boards |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.