Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 17

Safety and Effectiveness of Lurasidone in Patients with Schizophrenia: A 12-Week, Open-Label Extension Study

Authors Iyo M , Ishigooka J, Nakamura M , Sakaguchi R, Okamoto K, Mao Y, Tsai J, Fitzgerald A, Takai K , Higuchi T

Received 19 May 2021

Accepted for publication 24 July 2021

Published 16 August 2021 Volume 2021:17 Pages 2683—2695

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S320021

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Taro Kishi

Masaomi Iyo,1 Jun Ishigooka,2 Masatoshi Nakamura,3 Reiko Sakaguchi,4 Keisuke Okamoto,5 Yongcai Mao,6 Joyce Tsai,7 Alison Fitzgerald,8 Kentaro Takai,9 Teruhiko Higuchi10,11

1Department of Psychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan; 2Institute of CNS Pharmacology, Tokyo, Japan; 3Department of Data Science, Drug Development Division, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 4Department of Clinical Research, Drug Development Division, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 5Department of Clinical Operation, Drug Development Division, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 6Division of Data Science, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA; 7Division of Clinical Research, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA; 8Division of Clinical Operations, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA; 9Medical Affairs, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 10Japan Depression Center, Tokyo, Japan; 11National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan

Correspondence: Kentaro Takai Email [email protected]

Purpose: The goal of this study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of lurasidone among patients with schizophrenia in a 12-week open-label extension study.

Patients and Methods: Patients who completed a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study were enrolled in a 12-week open-label extension study with flexible dosing of lurasidone at 40 or 80 mg/day. Safety assessments included adverse events, vital signs, laboratory tests, and electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters. Effectiveness measures included the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score, Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale (CGI-S), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) and quality of life measure.

Results: A total of 289 patients were enrolled in the open-label extension study. Rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were low; akathisia was the most common TEAE with an incidence of 6.6%. There were 54 patients (18.7%) who discontinued the extension study, with 17 (5.9%) discontinuing due to adverse events. Minimal or no effects of lurasidone on weight, body mass index, metabolic parameters, prolactin, and ECG parameters were evident. There was continued improvement to week 12 in PANSS and CGI-S scores beyond the initial gains made during the prior 6-week double-blind study. Non-responders to lurasidone 40 mg/day in the prior 6-week study showed a mean (standard deviation) improvement from open-label baseline of 10.7 (13.8) points on the PANSS total score after lurasidone dose was increased to a modal dose of 80 mg/day during the extension study. Changes from double-blind baseline in CDSS and quality of life were maintained in the extension study.

Conclusion: Treatment with lurasidone 40 or 80 mg once daily (flexibly dosed) continued to be well tolerated with patients demonstrating further improvement in symptoms over the course of a 12-week open-label extension study in patients with schizophrenia.

Keywords: lurasidone, schizophrenia, antipsychotic, safety, effectiveness, open-label

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a disabling psychiatric disorder that is estimated to affect 21 million people worldwide.1 The severity and chronicity of this disorder result in substantial burden on the individual and society. These burdens are evident in terms of decreased quality of life and poor functioning, increased morbidity including cardiovascular disease, and lowered life expectancy.2–9

Negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, and mood symptoms all affect every day functioning in those with schizophrenia.10 Cognitive impairments and negative symptoms adversely affect the long-term functional outcomes in schizophrenia.11,12 To change the illness trajectory and reach recovery, continuous effective treatment together with a high level of safety and tolerability, are needed to prevent relapse and improve functioning.13

Lurasidone is a novel second-generation antipsychotic currently marketed in over 40 countries including the US, Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, Australia, Brazil, China, and Japan for the treatment of schizophrenia in recommended doses between 40 and 160 mg/day. This compound possesses high affinities for dopamine D2, serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)2A, 5-HT7, and noradrenaline α2C receptors as antagonist, and 5-HT1A as partial agonist. Compared with other atypical antipsychotics, lurasidone demonstrates similar binding affinities for the D2 and 5-HT2A receptors, but greater affinity for serotonin 5-HT1A receptors. Lurasidone displays weak affinity for 5-HT2C, histamine H1 or muscarinic M1 receptors which are thought to be involved with metabolic syndrome effects, weight gain and sedation.14 The pharmacokinetics of lurasidone are dose proportional within a range of 20–160 mg/day.

A meta-analysis of 8 short-term (6 week) placebo-controlled studies conducted in the US, Europe, Asia, and South America found that, in the treatment of schizophrenia, lurasidone (40–160 mg/day) was efficacious relative to placebo in terms of change in positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology.15 Lurasidone was also found in this meta-analysis to be well tolerated with minimal effects on body weight, and glucose and lipid parameters.15

Long-term continuation studies with lurasidone for patients with schizophrenia have been conducted over 6 to 22 months. These studies found continued efficacy and continued minimal effects on body weight and metabolic parameters.16–19 A recent 26-week, open-label study of lurasidone 40–80 mg/day extended these efficacy and safety findings to patients with schizophrenia from Asia (Japan, Taiwan, Korea and Malaysia).20 Two further unpublished 52-week studies involving Japanese patients with schizophrenia found continued efficacy and no clinically significant safety problems with lurasidone doses of 20 to 120 mg/day and 40 to 120 mg/day, respectively (Data on file, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.).

In a recent 6-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study (JEWEL study; EudraCT number: 2016-000060-42), lurasidone 40 mg/day demonstrated various efficacy and safety outcomes in a diverse patient population with acute schizophrenia, including patients from Japan.21 Since the JEWEL study adopted the inclusion/exclusion criteria of a US study that demonstrated the efficacy and safety of 80 and 160 mg/day of lurasidone,22 further confirmation of the impact of the long-term effects of lurasidone on patients recruited in the criteria of the US study, with extension to a Japanese population, is important. The goal of the present study was to evaluate the longer term safety and tolerability, and secondarily the effectiveness of open-label lurasidone 40 or 80 mg/day in patients with schizophrenia including patients from Japan who completed the JEWEL 6-week study and enrolled in a 12-week extension study.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a 12-week open-label extension study that followed a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group 6-week study.21 The initial 6-week study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lurasidone 40 mg/day administered to patients with acute schizophrenia. The patients had to meet the following key criteria: a Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS)23 total score ≥80; a PANSS item score ≥4 (moderate) on 2 or more of the following PANSS items: delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, suspiciousness, or unusual thought content at both screening and baseline; a score of 4 (moderately ill) or higher on the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness (CGI-S)24 at screening and baseline; an acute exacerbation of mainly positive symptoms. Patients were recruited at 73 clinical sites in 5 countries (Japan, Ukraine, Russia, Romania, Poland). In the extension study (clinical trial registration: EudraCT Number: 2016–000061-23) reported here, eligible patients who completed the short-term double-blind study, who were treated with either placebo or lurasidone 40 mg/day during the 6-week study, were treated with flexibly-dosed 40 or 80 mg/day of open-label lurasidone for an additional 12 weeks.

The study protocol and amendments received institutional review board/ethics committee review at each site. A list of the sites and Institutional Review Boards with permit numbers is provided in Tables S1-1 and S1-2. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment.

To be eligible for the 12-week extension study, patients needed to have completed the 6-week double-blind study and all assessments on the final visit of that phase. Excluded were patients judged to be an imminent risk of suicide or injury to self or others or who answered “yes” to item 4 (active suicidal ideation with some intent to act, without specific plan) or item 5 (active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent) on the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS),25 at the final visit of the preceding 6-week double-blind study, which also served as open-label baseline visit of the extension study. Also excluded were patients who exhibited evidence of severe tardive dyskinesia, severe dystonia, or other severe movement disorder, as determined by the investigator, or who required treatment with any potent cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors or inducers during the preceding double-blind study.

Drug Administration and Concomitant Medications

All patients received open-label lurasidone 40 mg/day during week 1 of the 12-week extension study. Beginning at day 8, flexible dosing to 80 mg/day was permitted, if judged clinically necessary. Thereafter, an increase or decrease in dose could occur at each visit. Study visits occurred at open-label baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 of the extension study. A follow-up visit occurred at week 13. During the 12-week extension study, study drug consisted of tablets containing lurasidone 40 mg and was administered orally, as one for 40 mg and two for 80 mg once daily, in the evening, with food or within 30 minutes after eating.

For the initial 6-week study, patients were required to discontinue prohibited medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and other psychotropics. During the open-label extension study, treatment with antidepressant medications (except fluvoxamine) and/or mood stabilizers (except carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine) could be initiated. Treatment with benztropine (≤6 mg/day) was permitted as needed during both the 6-week double-blind study and 12-week open-label study for the management of treatment-emergent movement disorders. Biperiden, trihexyphenidyl, diphenhydramine or promethazine were also permitted if benztropine was not available, or if a subject had an inadequate response or intolerability to benztropine treatment. Treatment with propranolol (≤120 mg/day) as needed for akathisia was permitted. Concomitant use of lorazepam, zolpidem, temazepam, brotizolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, zopiclone, or eszopiclone was permitted within limits during both the 6-week study and 12-week extension study. Treatment with fluoxetine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, additional antipsychotic medications, electroconvulsive therapy, herbal supplements (for psychotropic reasons), and antiarrhythmic drugs of Class 1A or of Class 3 were prohibited during the open-label extension study.

Safety Assessments

Safety endpoints during the 12-week extension study included reported treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), laboratory tests (Hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c], total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, serum prolactin), vital signs, waist circumference, body weight (from physical), body mass index (BMI), QTc interval determined from electrocardiography (ECG) measurements, and use of concomitant antiparkinsonian drugs. The clinician-rated Drug-Induced Extrapyramidal Symptom Scale (DIEPSS)26 was also administered to assess extrapyramidal symptoms induced by antipsychotics. Emergence of suicidality was evaluated using the C-SSRS. TEAEs, vital signs, body weight, DIEPSS, and C-SSRS were measured at each study visit including the week 13 follow-up visit. ECGs were conducted at open-label baseline and weeks 4 and 12 (or the early termination visit). The clinical laboratory panel including urinalysis was conducted at open-label baseline and weeks 4, 8, and 12. TEAEs of special interest were identified as extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperglycemia and new-onset diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, weight gain, and hypersensitivity. TEAEs were classified based on MedDRA Version 19.1.

Effectiveness Assessments

Effectiveness measures included the PANSS total score and the CGI-S, administered at open-label baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12. In addition, the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia score (CDSS)27 was administered at open-label baseline and weeks 4 and 12. Also evaluated were PANSS subscale scores and PANSS 5-factor Lindenmayer28 model scores including negative symptoms, excitement, cognitive disorders, positive symptoms, and anxiety/depression. The self-reported Euroqol-5 Dimensions-3 levels (EQ-5D-3L)29 was obtained at baseline and week 12. An additional outcome was time to all-cause discontinuation from open-label baseline.

Statistical Analysis

An “all patients enrolled” population was defined as all patients who provided informed consent for the open-label extension study. The safety population included patients who received at least 1 dose of open-label study drug during the extension study. An intent-to-treat (ITT) population was defined as all patients who received at least 1 dose of open-label study drug during the extension study, had both double-blind and open-label baseline PANSS total score assessments, and at least 1 post-open-label baseline PANSS total score assessment. Double-blind baseline is defined as the last non-missing measurement taken prior to or on the date of first dose of double-blind study medication (including unscheduled assessments) in the 6-week double-blind study. Open-label baseline is defined as the last non-missing assessment in the 6-week double-blind study. In addition to examination of the overall safety and ITT samples, the subgroup of patients from Japan was also examined for both safety and effectiveness. Data for the extension study were also examined for the patients who had received lurasidone 40 mg/day (lurasidone-lurasidone), and separately for those who had received placebo (placebo-lurasidone), during the prior 6-week double-blind study. Effectiveness during the extension study was also examined for those that failed to respond to lurasidone 40 mg/day during the prior 6-weeks double-blind study. Non-response was defined as less than a 20% reduction from double-blind study baseline to open-label study baseline on the PANSS total score. Alternative definitions of non-response were also examined, including percent improvement from double-blind baseline to open-label baseline <30% and open-label baseline ≥80.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize safety and effectiveness outcomes. No statistical inference methods were used. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated whenever appropriate. The primary safety analyses were summaries (number and percent of patients) of TEAEs, TEAEs leading to discontinuation, and serious adverse events (SAEs). Mean change from double-blind and open-label baseline to each of the post open-label baseline visits was summarized for vital signs, laboratory values, DIEPSS total score, PANSS total score, PANSS subscale scores, PANSS 5-factor Lindenmayer model scores, CDSS total score, CGI-S score, and EQ-5D-3L. For time to all-cause discontinuation from open-label baseline, the median and 25th percentile of time to discontinuation and their 95% CIs were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. For patients with missing assessment at week 12 of the extension study, a last observation carried forward (LOCF) endpoint was derived, using the last post-baseline value in the open-label study up to 7 days after the last dose of open-label study drug. All data analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 593 patients were screened to achieve 483 randomized (247 to lurasidone 40 mg/day and 236 to placebo) to the 6-week double-blind study (Figure 1). Of those 375 patients who completed the 6-week study, 289 enrolled in the 12-week extension study (148 from lurasidone 40 mg/day and 141 from placebo). A total of 54 patients (18.7%) discontinued the extension study. The primary reasons for discontinuation of the extension study were withdrawal by patient (9.7%) and adverse event (5.9%). All patients who enrolled in the extension study were included in the safety analyses. Two patients from the lurasidone 40 mg/day 6-week study group did not have assessments after the open-label baseline and therefore were excluded from the ITT population. Patient disposition for the subgroup of Japanese patients is provided in Table S2.

|

Figure 1 Patient disposition. Abbreviation: PI, principal investigator. |

The mean (standard deviation [SD]; range) age of the sample enrolled in the 12-week open-label study was 40.1 (11.2; 18–70) years (Table 1), and the majority of patients (257, 88.9%) were <55 years old. There were similar numbers of men and women. Sample sizes by country were Japan 71, Ukraine 124, Russia 82, Romania 9, and Poland 3. These characteristics were similar for lurasidone-lurasidone group compared to placebo-lurasidone group.

|

Table 1 Demographics and Open-Label Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Open-Label Treatment Period (Safety Population) |

Concomitant medications used over the course of the 12-week extension study included antiparkinsonian (n = 21, 7.3%), anxiolytics (n = 66, 22.8%), hypnotics/sedatives (n = 49, 17.0%), and other antipsychotics (n = 36, 12.5%); concomitant use of an antipsychotic was a protocol violation. Lorazepam (n = 55, 19%) was the most commonly used anxiolytic, while brotizolam (n = 24, 8.3%), eszopiclone (n = 12, 4.2%), and triazolam (n = 10, 3.5%) were the more commonly used hypnotics/sedatives.

Study Drug Exposure

The mean (SD) duration of days of study drug exposure was 75.4 (21.4), with a median of 84 days, and the overall mean (SD) daily dose of lurasidone during the extension study was 57.1 (16.6) mg/day (Table S3). A modal dose of lurasidone 40 mg/day in the extension study was provided to 153 (52.9%) patients (74 in lurasidone-lurasidone and 79 in placebo-lurasidone) and 80 mg/day was provided in the extension study to 136 (47.1%) patients (74 in lurasidone-lurasidone and 62 in placebo-lurasidone).

Safety

Treatment with lurasidone over the course of the 12-week extension study was generally well tolerated in the patients with schizophrenia. A total of 146 (50.5%) patients experienced 1 or more TEAEs during the study. Akathisia was the most frequently reported TEAE (6.6%), followed by nasopharyngitis (5.9%), and schizophrenia (5.5%) (Table 2). Rates of TEAEs were similar for both lurasidone-lurasidone and placebo-lurasidone groups. The incidence of TEAEs did not increase with duration of treatment (Table S4). The highest incidence of TEAEs occurred during the first month of open-label lurasidone treatment (110 patients, 38.1%).

|

Table 2 Summary of Adverse Events That Occurred in at Least 2% of Subjects in the Overall Population (Safety Population) |

Most of the TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity, and severe TEAEs occurred in 11 (3.8%) patients during the extension study. Study drug-related TEAEs occurred in 100 (34.6%) patients. SAEs occurred in 14 (4.8%) patients, with schizophrenia in 4.2%, and anxiety, impulsive behavior and suicide attempt in 0.3% each. Study drug discontinuation due to TEAEs was relatively low and occurred in 18 (6.2%) patients, with 10 of these discontinuing due to a drug-related TEAE. No deaths were reported during the study.

TEAEs of special interest occurred in relatively low frequencies. There were 28 (9.7%) patients who experienced any extrapyramidal TEAEs (11 in the lurasidone-lurasidone group and 17 in the placebo-lurasidone group). The most commonly experienced TEAE was akathisia (6.6%) followed by parkinsonism (2.1%). Hyperglycemia and new onset diabetes mellitus were experienced by 5.9%, and dyslipidemia by 0.7% during the extension study. There were 8 (2.8%) patients who reported a TEAE of weight gain. Hypersensitivity was experienced by 12 (4.2%) patients. None of the TEAEs of special interest were severe and none led to study discontinuation except for 2 patients who experienced hypersensitivity.

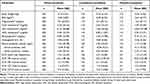

There were no clinically significant mean changes from double-blind or open-label baseline to endpoint in blood chemistry (including serum prolactin), hematology, or urinalysis (Table 3). For body weight (obtained from physical), few markedly abnormal (≥7.0%) decreases or increases were observed from open-label baseline (7 [2.4%] patients and 12 [4.2%] patients, respectively).

|

Table 3 Mean (SD) Change from Open-Label Baseline to Week 12 in Weight, BMI, Laboratory Parameters, and ECG Parameters (Safety Population) |

There were no clinically meaningful mean changes from double-blind or open-label baseline QTcB and QTcF intervals. The incidence of patients with abnormal post-baseline ECG results for heart rate, QRS, QT, and QTcF occurred in relatively low frequencies. No patient had a QTcB or QTcF interval >500 msec and an increase from double-blind or open-label baseline of ≥60 msec.

DIEPSS total scores, excluding the overall severity, were stable throughout the 12 weeks of the extension study. In the overall safety population, the mean (SD) change in DIEPSS total score from double-blind baseline and open-label baseline were −0.3 (1.3) and 0.0 (0.9) at Week 12 and −0.2 (1.3) and 0.0 (0.8) at LOCF endpoint, respectively. The DIEPSS overall severity scores largely remained none/normal (210 patients, 86.8%) to minimal/questionable (27 patients, 11.2%) following 12 weeks of open-label lurasidone treatment. There were no patients whose DIEPSS overall severity scores were moderate or severe at week 12.

The proportion of patients who had at least 1 occurrence of suicidal ideation as measured by the C-SSRS was low (2.4%, 7 of 289 patients). The number of patients with the most severe ideation overall included 6 with Type 1 and one with Type 4 who had one suicide attempt.

When the summaries of TEAEs were analyzed for Japanese patients who continued in the open-label extension study, lurasidone treatment at 40 or 80 mg/day was generally safe and well tolerated, with safety outcomes consistent with the findings in the overall population (Table S5).

Effectiveness

Treatment effectiveness was broadly evident across outcome measures, including maintenance of reductions from the 6-week double-blind study on the PANSS total score, PANSS subscale scores, and PANSS 5-factor Lindenmayer model scores throughout the 12-week, open-label extension study. For the extension study overall ITT population, the PANSS total score mean (SD) changes from double-blind and open-label baselines were −29.4 (17.6) and −8.8 (13.3) at LOCF endpoint of the extension study, respectively (Figure 2). Similar evidence for continued effectiveness during the extension study was seen on the CGI-S. The CDSS score tended to be the same as in the previous 6-week study (Table 4). Continued effectiveness of lurasidone during the extension study was also apparent for the subgroup of patients from Japan (Figure 3). The mean (SD) change in PANSS total score relative to open-label baseline was −8.2 (13.1) at week 12 and −6.1 (13.4) at LOCF endpoint for the Japanese extension study subgroup (Table S6). Changes on effectiveness measures were generally similar for other countries and by races (Table S7-1 and S7-2).

|

Table 4 Mean (SD) Change from Double-Blind and Open-Label Baseline to LOCF Endpoint in Secondary Efficacy Measures (ITT Population) |

The mean (SD) change in PANSS total score from double-blind and open-label baseline to LOCF endpoint, respectively, were −32.7 (17.7) and −7.8 (12.8) for patients with a modal dose of lurasidone 40mg/day (n = 151), and −25.7 (16.7) and −10.0 (13.7) for patients who had a modal dose of lurasidone 80mg/day (n = 136).

Among patients who failed to respond to lurasidone 40 mg/day during the 6-week double-blind study (non-responder, defined as percent reduction from double-blind baseline to open-label baseline <20%), those (n = 11) that received a modal flexible dose of 40 mg/day during the 12-week extension study showed a mean (SD) improvement on the PANSS total score of −15.7 (18.4) points from their double-blind baseline and −6.2 (16.7) points from their open-label baseline to LOCF endpoint (Table S8-1). The non-responders from the double-blind study (n = 28) who received a modal dose of 80 mg/day during the extension study showed even larger improvements, with a mean (SD) change of −17.1 (13.2) from double-blind baseline and −10.7 (13.8) from open-label baseline. Similar changes were evident for alternative definitions of non-response (Tables S8-2 and S8-3). Furthermore, the Japanese subgroup showed the same tendency of increase effect as the whole population (Tables S9-1–S9-3).

Measures of quality of life (EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS) also improved over time with lurasidone treatment (Table 4). At Week 12, there was an overall mean (SD) increase of 0.097 (0.190) and 0.028 (0.141) relative to double-blind and open-label baseline on EQ-5D-3L index scores, respectively. Similarly, after 12 weeks of lurasidone treatment, there was an overall mean (SD) increase in EQ VAS scores of 16.8 (24.1) and 5.3 (18.8) relative to double-blind and open-label baseline, respectively.

A Kaplan–Meier plot for time to all-cause discontinuation is presented in Figure 4. The 25th percentile was not reached and median time to study treatment discontinuation could not be estimated. The probability of patients prematurely discontinuing from lurasidone treatment during the extension study was similar for both lurasidone-lurasidone and placebo-lurasidone groups.

Discussion

The results of this 12-week extension study demonstrated that treatment with lurasidone 40 or 80 mg/day (flexibly dosed) was generally well tolerated in the patients with schizophrenia including Japanese subgroup. Rates of TEAEs were similar for patients who had received prior placebo vs lurasidone in the prior 6-week double-blind study. Of particular note, there was a low occurrence of TEAEs of special interest (extrapyramidal, hyperglycemia and new-onset diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, weight gain, hypersensitivity). None of these TEAEs severe and hypersensitivity was the only TEAE of special interest that led to discontinuation, in two patients.

The pattern of specific TEAEs evident during the 12-week open-label extension study was consistent with common adverse events reported in previous lurasidone short-term double-blind clinical studies. In two of the short-term studies of lurasidone for schizophrenia, the largest differences between drug and placebo in the incidence of specific adverse events over the course of 6 weeks of treatment were for akathisia, somnolence, and abdominal discomfort (or nausea).30,31 In addition to schizophrenia and nasopharyngitis, akathisia and nausea were also among the more common adverse events during the current 12-week extension study, though occurring at a low overall incidence (akathisia at 6.6% of patients was the most common TEAE). Although study designs differ, the incidence of akathisia for some antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia has been reported32 to be 3–13% across various studies, and the current result is also within that range. The lack of noticeable effects on weight, BMI, metabolic parameters, prolactin, and ECG parameters in the current study is consistent with previous safety findings,30,31 and the double-blind study that preceded the extension study reported here.21 It is speculated that these minimal effects on weight and metabolic parameters are due to the lack of clinically relevant affinity of lurasidone for the receptors (H1-histamine and 5-HT2c) that are believed to be associated with weight gain.14,33 The continued minimal effect of lurasidone on metabolic parameters across 12 weeks of extension treatment following 6 weeks of initial treatment is of particular clinical importance given the fact that the medical problems associated with metabolic syndrome develop over time and that individuals with schizophrenia are at high risk for metabolic syndrome.34

Patient symptoms, as measured by the PANSS total, subscale scores, 5-factor Lindenmayer model scores, and CGI-S showed continued improvement during the 12-week extension study beyond the gains made during the initial 6-week double-blind study. This was evident for patients who received either lurasidone 40 mg/day or placebo during the 6-week double-blind study.

Non-responders to lurasidone 40 mg/day during the 6-week double-blind study were administered lurasidone 80 mg/day during the 12-week extension study and showed improvement in symptoms. This dose-increase effect was also observed in the Japanese subpopulation of patients. In a previous study, a lurasidone dose increase from 80 to 160 mg/day for early (2 weeks) non-responders resulted in significant improvement in PANSS total scores.35 As some treatment guidelines recommend assessing efficacy with optimal dose in at least 2–4 weeks,36,37 including multiple episodes,38 this dose increase range would be more relevant to real world clinical practice of lurasidone treatment of schizophrenia.

Negative symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, and mood disorders often remain after suppressing positive symptoms of schizophrenia such as hallucinations and delusions.39–41 Although second generation antipsychotics have been reported to be effective not only for positive symptoms but also for negative symptoms, adverse events such as weight gain and movement disorders caused by some of these agents often prevent continued treatment with the same agent.42,43 Therefore, high safety are required to maintain good adherence during the maintenance phase to prevent relapse. In previous studies, treatment with lurasidone compared to placebo has resulted in a broad range of benefits including improvements in depressive symptoms and the cognitive impairments of schizophrenia.44,45 Such broad improvements were also evident in the current study, in which improvements in all of the PANSS 5-factor Lindenmayer model scores were demonstrated over the course of the 12-week extension study along with good tolerability and minimal changes in metabolic parameters and weight gain. In regard to relapse, a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal 28-week study of lurasidone 40–80 mg/day for schizophrenia previously found a significant advantage of lurasidone compared to placebo in time to relapse with a 33.7% reduction in risk of relapse.46 The safety profile and wide-ranging efficacy of lurasidone shown in previous and the current study may meet the therapeutic needs of the acute and subsequent phase of schizophrenia.

Study Limitations

There are study limitations that should be noted. First, the duration of the current study is 12 weeks, which is not enough to investigate long-term safety and efficacy profiles (relapse/recurrence of symptoms). Second, the current study did not include a comparator treatment that would provide more relevant interpretation of safety and efficacy. However, in previous longer-term studies of lurasidone, the first adverse events occurred most often within 1–12 weeks and therefore the results of the current 12-week study would help to capture early signs of adverse events occurring in long-term treatment.

Conclusions

Safety findings in this 12-week open-label extension study were consistent with the results from the prior 6-week double-blind study as well as previous studies of lurasidone in adult patients with schizophrenia. There were minimal or no effects of 40 or 80 mg/day (flexibly dosed) lurasidone on weight, BMI, metabolic parameters, prolactin, and ECG parameters. Twelve weeks of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Lurasidone at 80 mg/day was effective in improving positive and negative symptoms in non-responder patients previously treated with lurasidone 40 mg/day.

Data Sharing Statement

Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma makes individual patient, de-identified data sets and associated clinical documents such as study protocol, statistical analysis plan and clinical study report available upon request via the Clinical Study Data Request site (https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/ Study-Sponsors.aspx). Access is provided after a research proposal is submitted and has received approval from the Independent Review Panel and after a Data Sharing Agreement is in place. Access is provided for an initial period of 12 months but an extension can be granted, when justified, for up to another 12 months.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and providers who participated in the study. Medical writing assistance was provided by Edward Schweizer, MD, of Paladin Consulting Group, Inc. (Princeton, NJ).

Funding

The study was funded by Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.

Disclosure

Dr Iyo reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Jansen Pharmaceutical K.K, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry Co., Ltd, and Eli Lilly Japan, and also reports grants and personal fees from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., personal fees and other from MSD K.K. Dr Ishigooka reports personal fees from Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Eli Lilly Japan, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co, Alfresa Pharma, Lundbeck, and Yoshitomiyakuhin. Dr Higuchi reports personal fees from Meiji Seika Pharma, MSD, Allergan, Eisai, Pfizer, Janssen, Lundbeck, Shionogi, Yoshitomi, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Mochida, Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Eli Lilly, and Takeda. M Nakamura, R Sakaguchi, K Okamoto, and K Takai are full-time employees of Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. Y Mao and A Fitzgerald are full-time employees of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. J Tsai was an employee of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals at the time this study was conducted, but is currently at COMPASS Pathways. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Schizophrenia fact sheet; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia.

2. Palmer B, Pankratz V, Bostwick J. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):247–253. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247

3. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123

4. Daumit G, Anthony C, Ford D, et al. Pattern of mortality in a sample of Maryland residents with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2–3):242–245. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.006

5. Tandberg M, Sundet K, Andreassen O, Melle I, Ueland T. Occupational functioning, symptoms and neurocognition in patients with psychotic disorders: investigating subgroups based on social security status. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(6):863–874. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0598-2

6. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

7. Evensen S, Wisløff T, Lystad J, Bull H, Ueland T, Falkum E. Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: a population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophr Bull. 2015;42(2):476–483. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv141

8. Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):163–180. doi:10.1002/wps.20420

9. Hjorthoj C, Sturup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):295–301. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

10. Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Harvey PD. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(5):505–511. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022

11. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM. Symptomatic and functional recover from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):473–479. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473

12. Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495–506. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495

13. Gitlin M, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, et al. Clinical outcome following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1835–1842. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1835

14. Ishibashi T, Horisawa T, Tokuda K, et al. Pharmacological profile of lurasidone, a novel antipsychotic agent with potent 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 (5-HT7) and 5-HT1A receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(1):171–181. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.167346

15. Zheng W, Cai DB, Yang XH, et al. Short-term efficacy and tolerability of lurasidone in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:244–251. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.06.005

16. Citrome L, Cucchiaro J, Sarma K, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of lurasidone in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind, active-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(3):165–176. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32835281ef

17. Stahl SM, Cucchiaro J, Simonelli D, Hsu J, Pikalov A, Loebel A. Effectiveness of lurasidone for patients with schizophrenia following 6 weeks of acute treatment with lurasidone, olanzapine, or placebo: a 6-month, open-label, extension study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(05):507–515. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08084

18. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Xu J, Sarma K, Pilalov A, Kane JM. Effectiveness of lurasidone vs. quetiapine XR for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind, noninferiority study. Schizophr Res. 2013;147:95–102. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.03.013

19. Correll CU, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, Hsu J. Long-term safety and effectiveness of lurasidone in schizophrenia: a 22-month, open-label extension study. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(5):393–402. doi:10.1017/S1092852915000917

20. Higuchi T, Ishigooka J, Iyo M, Hagi K. Safety and effectiveness of lurasidone for the treatment of schizophrenia in Asian patients: results of a 26-week open-label extension study. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;12(1):e12377. doi:10.1111/appy.12377

21. Iyo M, Ishigooka J, Nakamura M, et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in acutely psychotic patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75(7):227–235. doi:10.1111/pcn.13221

22. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Sarma K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2013;145(1–3):101–109. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.009

23. Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi:10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

24. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, (revised), (ADM) 76–338 edn. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976.

25. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

26. Inada T, Beasley C, Tanaka Y, Walker D. Extrapyramidal symptom profiles assessed with the drug-induced extrapyramidal symptom scale: comparison with Western scales in the clinical double-blind studies of schizophrenic patients treated with either olanzapine or haloperidol. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:39–48. doi:10.1097/00004850-200301000-00007

27. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the calgary depression scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1993;163(S22):39–44. doi:10.1192/S0007125000292581

28. Lindenmayer JP, Bernstein-Hyman R, Grochowski S. A new five factor model of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 1994;65(4):299–322. doi:10.1007/BF02354306

29. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. doi:10.3109/07853890109002087

30. Meltzer H, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and olanzapine-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):957–967. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10060907

31. Nasrallah H, Silva R, Phillips D, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of acutely psychotic patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(5):670–677. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.020

32. Chow CL, Kadouh NK, Bostwick RJ, VanderBerg AM. Akathisia and newer second-generation antipsychotic drugs: a review of current evidence. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40(6):565–574. doi:10.1002/phar.2404

33. Kroeze WK, Hufeisen SJ, Popadak BA, et al. H1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(3):519–526. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300027

34. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–347. doi:10.1002/wps.20252

35. Loebel A, Silva R, Goldman R, et al. Lurasidone dose escalation in early nonresponding patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(12):1672–1680. doi:10.4088/JCP.16m10698

36. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]; 2014. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178.

37. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia.

38. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71–93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp116

39. Arndt S. A longitudinal study of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. Prediction and patterns of change. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(5):352–360. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170026004

40. Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):24–32. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24

41. Austin SF, Mors O, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al. Long-term trajectories of positive and negative symptoms in first episode psychosis: a 10 year follow-up study in the OPUS cohort. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1–2):84–91. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.021

42. Halliday J, Farrington S, Macdonald S, et al. Nithsdale schizophrenia surveys 23: movement disorders. 20-year review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(5):422–427. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.5.422

43. Hasnain M, Fredrickson SK, Vieweg WV, Pandurangi AK. Metabolic syndrome associated with schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(3):209–216. doi:10.1007/s11892-010-0112-8

44. Harvey PD, Siu CO, Hsu J, Cucchiaro J, Maruff P, Loebel A. Effect of lurasidone on neurocognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia: a short-term placebo- and active-controlled study followed by a 6-month double-blind extension. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1373–1382. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.08.003

45. Nasrallah HA, Cucchiaro JB, Mao Y, Pikalov AA, Loebel AD. Lurasidone for the treatment of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of 4 pooled, 6-week, placebo‐controlled studies. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(2):

46. Tandon R, Cucchiaro J, Phillips D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of lurasidone for the maintenance of efficacy in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(1):69–77. doi:10.1177/0269881115620460

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.