Back to Journals » ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research » Volume 8

Relative cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Brazil

Authors Guest JF , Yang AC, Oba J, Rodrigues M, Caetano R, Polster L

Received 24 May 2016

Accepted for publication 18 July 2016

Published 19 October 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 629—639

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S113448

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Giorgio Colombo

Julian F Guest,1,2 Ariana C Yang,3 Jane Oba,4 Maraci Rodrigues,5 Rosane Caetano,6 Lilian Polster7

1Catalyst Health Economics Consultants, Northwood, Middlesex, UK; 2Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, King’s College, London, UK; 3Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo & Universidade Estadual de Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil; 4Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil & Hospital Municipal Menino Jesus, São Paulo, Brazil; 5Department of Gastroenterology, University of São Paulo School of Medicine, São Paulo, Brazil; 6General Pediatrician, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 7General Pediatrician, São Paulo, Brazil

Objective: To estimate the cost-effectiveness of three alternative dietetic strategies for cow’s milk allergy in Brazil: 1) using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHCF; Nutramigen) as a first-line formula, but switching to an amino acid formula (AAF) if infants remain symptomatic; 2) using an AAF as a first-line formula and then switching to an eHCF after 4 weeks once infants are symptom-free, but switching back to an AAF if infants become symptomatic; and 3) using an AAF as a first-line formula and keeping all infants on that formula. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the Brazilian public health care system, Sistema Único de Saude.

Methods: Decision modeling was used to estimate the probability of immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and non-IgE-mediated allergic infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula. The models also estimated the Sistema Único de Saude cost (at 2013/2014 prices) of managing infants over 12 months after starting a formula, as well as the relative cost-effectiveness of each of the dietetic strategies.

Results: The probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula was higher among infants with either IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated allergy who were initially fed with an eHCF, compared with those who were initially fed with an AAF. The total health care cost of initially feeding an eHCF to cow’s milk allergic infants was less than that of initially feeding both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated infants with an AAF.

Conclusion: Within the study’s limitations, using an eHCF instead of an AAF for the first-line management of newly-diagnosed infants with cow’s milk allergy affords a cost-effective use of publicly funded resources, since it improves the outcome for less cost.

Keywords: amino acid formula, Brazil, cost-effectiveness, cow’s milk allergy, extensively hydrolyzed formula

Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is an immunologically mediated reaction to the proteins in cow’s milk1 and is the most common food allergy in Brazil.2 CMA has an estimated annual prevalence of 0.02–0.03 in children <1 year of age.3 The affected children generally acquire tolerance to cow’s milk proteins within the first 5 years of life,4 although the allergy can persist until late in life.5,6 Elimination of cow’s milk proteins from a child’s diet and challenge tests are essential for diagnosing and treating this allergy,7 and for infants this necessitates the use of a hypoallergenic formula instead of standard infant formulas.7

In a recent observational study in Italy, an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHCF; Nutramigen) was found to accelerate the development of tolerance to cow’s milk in infants with CMA compared to those who received an amino acid formula (AAF).8 Otherwise healthy cow’s milk allergic infants without comorbidities were prescribed a formula by a family paediatrician or general physician. Then, 15–30 days after starting the formula, the infants were referred to a tertiary pediatric allergy center for a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) to confirm the diagnosis of CMA. Tolerance to cow’s milk was assessed at 12 months from the start of the formula by a full anamnestic and clinical evaluation, skin prick test, atopy patch test, and oral food challenge. Clinical acquisition of tolerance was defined by the presence of a negative DBPCFC over a 7-day postchallenge observational period. Infants with negative DBPCFC were reevaluated after 6 months to validate the persistence of tolerance to cow’s milk.8 After 12 months, significantly more infants fed with an eHCF (43.6%) were found to have developed oral tolerance to cow’s milk, compared to those fed with an AAF (18.2%).8 Data from this study (kindly provided by the study’s authors) were used for decision modeling to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of using different first-line formulas for managing cow’s milk allergic infants in Italy.9

There has been much discussion in Brazil about general pediatricians initially treating all infants presenting with the symptoms of CMA with an AAF and then switching to an extensively hydrolyzed formula once infants become symptom-free. Notwithstanding this, the comparative health economic impact of extensively hydrolyzed formulas and AAFs in Brazil is unknown, and therefore, dietetic choices are based largely on their safety, nutritional value, and purchase cost. Hence, the objective of the current study was to amend the Italian decision models9 to estimate the cost-effectiveness of using three alternative dietetic strategies in Brazil, from the perspective of the Brazilian public health care system, Sistema Único de Saude (SUS): 1) using an eHCF as a first-line formula, but switching to an AAF if infants remain symptomatic; 2) using an AAF as a first-line formula and then switching to an eHCF after 4 weeks once infants are symptom-free, but switching back to an AAF if infants become symptomatic; and 3) using an AAF as a first-line formula and keeping all infants on that formula.

Methods

Economic model

The Italian decision models (as previously described9) were adapted to reflect the structure of the health care system in Brazil and the context in which CMA is managed in this country. Similarly, patients’ pathways and resource use were adapted using estimates derived from a panel of general pediatricians (n=9), pediatric gastroenterologists (n=13), and pediatric allergists (n=9). The models considered three dietetic strategies: 1) using an eHCF as a first-line formula, but switching to an AAF if infants remain symptomatic; 2) using an AAF as a first-line formula and then switching to an eHCF after 4 weeks once infants are symptom-free, but switching back to an AAF if infants become symptomatic (eHCF-AAF); and 3) using an AAF as a first-line formula and keeping all infants on that formula. The period of the models was up to 12 months from starting a formula or when an infant developed tolerance to cow’s milk if that occurred sooner. Ethical approval and patient consent were not required as this was an economic modeling study and not a patient cohort analysis.

Model inputs – clinical outcomes

The models were populated with data from an observational study (as previously described).8,9 The probability of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk at different time points was calculated from the percentages of infants who developed oral tolerance to cow’s milk after being fed with a formula, as previously described for our Italian models.9

Model inputs – resource use

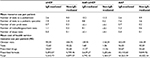

The models were populated with estimates of health care resource use pertaining to the management of infants with CMA in Brazil. These estimates were based on the clinical experiences of 31 pediatricians (Table 1).

| Table 1 Estimates from pediatricians Abbreviations: GP, general pediatrician; IgE, immunoglobulin E; PA, pediatric allergist; PG, pediatric gastroenterologist. |

The general pediatricians who participated in this study each see a mean of <70 infants with suspected CMA per annum, with a mean age at presentation of ~3 months (range 1–6 months). According to these pediatricians, 85% of infants with immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated allergy and 15% of those with non-IgE-mediated allergy are expected to be referred to a pediatric specialist (ie, gastroenterologist or allergist) for further investigations and confirmation of diagnosis. The pediatric gastroenterologists who participated in this study each see a mean of 70 infants with CMA per annum, compared to 30 infants per annum seen by the pediatric allergists. The mean age at presentation to a specialist was estimated to be ~4 months (range 2–7 months).

All the pediatricians would recommend a cow’s milk elimination diet and prescribe a substitute formula for the affected infants. At the initial visit to a general pediatrician, 60% of infants would generally be prescribed an extensively hydrolyzed formula. The other infants would receive either a soy-based formula, a partially hydrolyzed formula, or AAF. Over 95% of infants referred to a pediatric allergist would generally be prescribed an extensively hydrolyzed formula at the first visit. In contrast, an estimated one-third of infants would be prescribed an extensively hydrolyzed formula at the first visit to a pediatric gastroenterologist. The other two-thirds would be prescribed an AAF at the first visit and would generally remain on that formula. In addition, an estimated 20% of infants would be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor or prokinetic for ~7 days, 40% an emollient for 6–12 months, 20% a corticosteroid for ~7 days, and 40% an antihistamine for up to 1 month.

The interviewed pediatricians prescribe formula based on an infants’ age and weight. Therefore, the prescribed volumes that have been incorporated in models were consistent with the estimates previously described for our Italian study.9

Model outputs

The primary measure of clinical effectiveness was the probability of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula.

Unit costs in Brazilian Real at 2013/2014 prices (Table 2)10,11 were assigned to the estimates of resource use in the models in order to calculate the cost of health care resource use funded by the SUS over 12 months from the start of a formula.

| Table 2 Unit costs in R$ at 2013/2014 prices Note: Data from Ministry of Health (Brazilian SUS – SIGTAP)10 and Brasindice.11 Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formula; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; R$, Brazilian Real. |

The models were used to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of the three dietetic strategies in terms of the “incremental cost per additional infant who developed tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula” in Brazil. This was calculated using a previously described methodology,9 as the difference between the expected costs of two alternative dietetic strategies divided by the difference between the expected outcomes of the alternative strategies in terms of the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk. If one of the dietetic strategies improved the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk for less cost, it was considered to be the dominant (cost-effective) dietetic strategy. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the SUS.

Sensitivity analyses

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were undertaken (10,000 iterations of each model) by simultaneously varying the probabilities, clinical outcomes, resource use values, and unit costs within the models to assess uncertainty in the results. The distributions used were similar to those previously described for our Italian models.9 Using the outputs from these analyses, an estimation was made of the probability of being cost-effective at different thresholds of incremental cost per additional infant who developed tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were also performed to identify how the incremental cost-effectiveness of the alternative dietetic strategies would change by varying different model inputs. The budget impact and resource implications of starting the infants with each of the dietetic strategies under investigation compared with current practice were also estimated for the annual cohort of newly-diagnosed infants with CMA in Brazil.

Results

Probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk

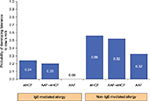

The probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk was higher among infants who were initially fed with an eHCF (Figure 1). Also, the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk was higher among those infants with non-IgE-mediated CMA compared to those with IgE-mediated allergy.

Health care resource use and corresponding costs

Use of health care resources is expected to be less among infants who are initially managed with an eHCF compared to those managed with the other dietetic strategies (Table 3). Hence, the total health care cost of initially feeding infants with an eHCF was estimated to be less than that of feeding infants with an AAF (Table 3). Furthermore, initially feeding infants with an eHCF instead of an AAF is expected to free up health care resources for alternative use by other patients.

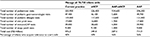

Cost-effectiveness analyses

Of the three dietetic strategies, use of an eHCF resulted in the lowest 12-month cost from the start of a formula and the highest probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk among both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated allergic infants (Table 4). Hence, initial feeding with an eHCF was found to be a dominant strategy when compared to starting feeding with an AAF (Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed (Figure 2A and B) to estimate the distribution of expected SUS cost differences between the alternative dietetic strategies over 12 months from starting a formula and expected differences in the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk between the alternative dietetic strategies by 12 months. Using these distributions, it was estimated that the probability of an eHCF being cost-effective compared to an AAF–eHCF and an AAF was 0.62 and 0.84, respectively, and the probability of an AAF–eHCF being cost-effective compared to an AAF was 0.81 at all cost-effectiveness thresholds, for both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated allergic infants.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses (Table 5) demonstrated that changes in the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk at different time points can potentially change the results. So too can changes in the number of cans of formula being prescribed. However, the relative cost-effectiveness of the three dietetic strategies was not sensitive to changes in any other model input.

| Table 5 Deterministic sensitivity analyses Abbreviations: AAF, amino acid formula; eHCF, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; IgE, immunoglobulin E; R$, Brazilian Real; SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde. |

Budget impact and resource implications of managing CMA

There are an estimated 2.83 million live births in Brazil per annum,12 and the annual incidence of CMA is reported to be 0.025.13 Hence, there are an estimated 70,750 new CMA-affected infants per annum in Brazil. Using the distribution of formula use estimated from the interviewed pediatricians, current management of all 70,750 newly-diagnosed infants was estimated to result in 42% of the cohort developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months from starting a formula, and a cost to the SUS of R$ 476.3 million (Table 6). If all these infants were initially managed with an eHCF, it is expected that 50% of the cohort would develop tolerance to cow’s milk and there would be 24,500 fewer visits to general pediatricians, 2,800 fewer visits to pediatric specialists, 700 fewer diagnostic tests, and a 27% cost reduction to the SUS of R$ 126.9 million. If all these infants were initially managed with an AAF followed by an eHCF (AAF–eHCF), it is expected that 46% of the cohort would develop tolerance to cow’s milk and there would be 383,700 more visits to general pediatricians, 147,200 fewer visits to pediatric specialists, 58,500 fewer diagnostic tests, and a 19% cost reduction to the SUS of R$ 88.9 million. If all these infants were initially managed with an AAF and not switched to an extensively hydrolyzed formula, it is expected that 26% of the cohort would develop tolerance to cow’s milk and there would be 45,400 more visits to general pediatricians, 5,200 more visits to pediatric specialists, 1,500 more diagnostic tests, and a 49% cost increase to the SUS of R$ 235.6 million.

Discussion

This study assessed the cost-effectiveness of using three alternative dietetic strategies for managing cow’s milk allergic infants in Brazil. The analysis was based on the only comparative analysis of an eHCF with an AAF that was available at the time of performing this study, which had separately assessed tolerance acquisition to cow’s milk in IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated allergic infants.8 This comparative analysis was an observational study in which the dietary effect of each formula was measured under controlled conditions. Nevertheless, the infants were not randomized to their formula, sample sizes were small in absolute terms and unbalanced between the groups, and resource use was not recorded.8 The study’s authors made every attempt to overcome the nonrandomized study design and account for any baseline differences between the groups.8 The inherent uncertainty of using data from this observational study was addressed, to some extent, by our extensive sensitivity analyses.

The relative cost-effectiveness of an eHCF in Brazil is consistent with the findings from our recent studies in Spain and Italy, which also found that initial use of an eHCF as a first-line management for CMA was cost-effective when compared with an AAF.9,14 We also found that in clinical practice in the US and UK, more cow’s milk allergic infants who were initially fed with an eHCF were successfully managed, compared to those who were fed with an AAF.15,16 These two studies also showed that initial dietary management with an eHCF instead of an AAF affords a more cost-effective use of health care resources since it reduced costs and released health care resources for alternative use within the system without impacting on the time needed to manage the allergy.15,16

The Brazilian Food Allergy Guidelines recommend 8 weeks of a diagnostic elimination diet with an extensively hydrolyzed formula in infants <6 months of age prior to an oral food challenge.17 However, based on the interviews with 31 pediatricians across Brazil, it would appear that the guidelines are not being followed by about one-third of general pediatricians and two-thirds of pediatric gastroenterologists. Moreover, according to our estimates, only 30% of all infants are referred to a pediatric specialist. The other 70% are managed exclusively by a general pediatrician and less than half of these infants would undergo any type of diagnostic test. Moreover, they would not undergo an oral food challenge until they had been fed with a formula for 6, 9, or 12 months. This is consistent with the findings of others who reported that use of a food challenge has been limited.18 Instead, a diagnosis of food allergy is usually established based on clinical history, physical examination, presence of specific IgE, and restricted diets.18 Notwithstanding this, it is important to note that results from skin prick tests and measurements of specific IgE are markers of sensitization. The DBPCFC remains the standard for diagnosing food allergy.19 However, given the time-intensive nature of the DBPCFC, a single-blind or open food challenge is used more often in clinics in Brazil. This reflects the practical difficulty of performing challenges on non-IgE-mediated allergic infants who may react as late as 1 or 2 weeks to a cow’s milk protein challenge.

It has been reported that using an AAF as a diagnostic tool for CMA followed by treatment according to current practice is cost-effective, when compared with managing infants according to current practice in Brazil.20,21 However, this analysis20,21 assumed that all infants treated with an AAF would be successfully managed and it did not account for differences in the probability of tolerance acquisition to cow’s milk between different formulas. It has been shown in clinical practice that fewer infants fed with an AAF acquire tolerance to cow’s milk than those fed with an eHCF, a soy formula, or a hydrolyzed rice formula.8 Also, findings from a recent DBPCFC study found an estimated 50% of infants aged <4 months remained symptomatic on an AAF.22 Furthermore, in our UK study of 295 infants with CMA who were followed up for a year,16 more AAF-treated infants received prescriptions for short-term use of bronchodilators than eHCF-treated infants (odds ratio 2.4 [95% confidence interval: 1.09; 5.29]; P<0.03), although patients in both groups were matched (Guest et al, unpublished data, 2012). This difference in requirement for bronchodilators may be indicative of a propensity to develop respiratory disease, and warrants further research. Accordingly, the costs estimated in the study on using an AAF as a diagnostic tool,20,21 particularly those for infants being fed with an extensively hydrolyzed formula, are likely to have been overestimated, since costs were attributed to patient management when infants are likely to have acquired tolerance to cow’s milk and no longer require a hypoallergenic formula. Consequently, their estimate of symptom-free days20,21 is potentially inaccurate, as is their conclusion.20,21 According to our analysis, feeding an AAF to a suspected CMA infant for 4 weeks and then switching to an eHCF would increase resource use and the corresponding SUS costs by 11%, when compared with using an eHCF as the initial formula. It would also reduce the probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk at 12 months from starting a formula by 8%.

Our economic analysis has several limitations. The decision models may not necessarily reflect the clinical outcomes associated with managing a large cohort of infants in clinical practice. The models were informed with assumptions about treatment patterns from 31 pediatricians, who are based at different centers in eleven different towns/cities across Brazil. Hence, the estimated levels of health care resource use incorporated into the models may not be representative of the whole of Brazil. Also, the models were based on clinical outcomes from an Italian study,8 which may not necessarily be reproducible in Brazil. Hence, a controlled study of alternative formulas is required to assess tolerance acquisition to cow’s milk among allergic infants in Brazil, in order to validate the measures of clinical effectiveness in this study. The analysis estimated the cost-effectiveness of managing infants up to 12 months from starting a formula and does not consider the potential impact of managing infants who remain allergic beyond that period. Infants with comorbidities were excluded from the observational study.8 Hence, this economic analysis does not consider the impact that factors such as comorbidities, underlying disease severity, and pathology of underlying disease may have on the results. Also, the analysis does not consider the suitability of infants to receive different formulae. Only direct health care costs borne by the SUS have been estimated and indirect costs incurred by society as a result of employed parents taking time off work were excluded. Also, changes in quality of life and improvements in general well-being of sufferers and their parents, as well as parents’ preferences were excluded. Consequently, this study may have underestimated the relative cost-effectiveness of an eHCF.

Despite these limitations, the analysis showed that proportionally more infants in Brazil who are initially fed with an eHCF are likely to develop tolerance to cow’s milk compared to those initially fed with an AAF, over the initial 12 months after starting a formula. Furthermore, infants who develop tolerance to cow’s milk no longer require any management or feeding with a hypoallergenic formula. Consequently, initially feeding an eHCF to the annual cohort of 70,750 new CMA-affected infants in Brazil, instead of the current mix of formulas, has the potential to increase the percentage of infants developing tolerance to cow’s milk from 42% to 50%. It also has the potential to lead to a reduction of 27,300 pediatrician visits and decrease in health service costs by up to R$ 126.9 million. Hence, initially using an eHCF to treat cow’s milk allergic infants has the potential to release health care resources for alternative use within the system.

For the purpose of the budget impact analysis, the annual incidence of CMA was assumed to be 0.025.13 However, the actual epidemiology of CMA in Brazil is unknown. Furthermore, an increasing number of patients in Brazil are developing allergies to local foods such as pineapple, papaya, pequi, and manioc.2 Reference centers have now been created to support the increasing demand of food allergy, offering allergy training programs that include clinical experience in oral food challenges and other diagnostic tests.

Conclusion

Within the study’s limitations, first-line management of newly-diagnosed cow’s milk allergic infants with an eHCF instead of an AAF affords a cost-effective use of publicly funded resources, since it improves outcome, releases health care resources for alternative use, and reduces costs to the SUS.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following general pediatricians for their contributions: Dra. Denise A. Brasileiro, Belo Horizonte, MG; Dr. João da Costa Pimentel Filho, Brasília, DF; Dr. Luís Felipe da S. Mader, Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Dr. Marcelo Silber, São Paulo, SP; Dra. Mônica C. de Lima Pires, Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Dr. José Nélio Cavinatto, São Paulo, SP; and Dr. Tadeu Fernando Fernandes, Campinas, SP.

The authors wish to thank the following pediatric gastroenterologists for their contributions: Dr. Aderbal Sabrá, UnigranRio, RJ; Dra. Cristina Palmer Barros, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, MG; Dra. Cristina Targa Ferreira, Hospital da Criança Santo Antônio, Santa Casa de Porto Alegre, RS; Dr. Hugo da Costa Ribeiro Júnior, Universidade Federal da Bahia, BA; Dr. José Cesar da Fonseca Junqueira, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Dr. José Vicente Spolidoro, Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS; Dr. Magno Cardoso Veras Neto, Belo Horizonte, MG; Dr. Mário C. Vieira, Hospital Pequeno Príncipe, Curitiba, PR; Dr. Mauro Batista de Morais, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP; Dra. Roberta Paranhos Fragoso, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, ES and Dra. Selma D. T. Sabrá, UnigranRio, RJ.

The authors wish to thank the following pediatric allergists for their contributions: Dra. Ana Paula B. Moschione Castro, Universidade de São Paulo, SP; Dr. Bruno A. P. Barreto, Universidade Estadual do Pará, Belém, PA; Dra. Cristina Miuki Abe Jacob, Universidade de São Paulo, SP; Dra. Corina Toscano Sad, Belo Horizonte, MG; Dr. Evandro Alves do Prado, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Dr. Fábio Kuschnir, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Dra. Fátima Rodrigues Fernandes, Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual, SP; and Dra. Renata R. Cocco, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP.

Disclosure

This study was supported with an unrestricted research grant from Mead Johnson Nutrition, São Paulo, Brazil. However, Mead Johnson Nutrition had no influence on the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Mead Johnson Nutrition. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to disclose in this work.

References

Allen KJ, Koplin JJ. The epidemiology of IgE-mediated food allergy and anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012;32(1):35–50. | ||

Rosario-Filho NA, Jacob CM, Sole D, et al. Pediatric allergy and immunology in Brazil. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(4):402–409. | ||

Rona RJ, Keil TK, Summers C, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):638–646. | ||

Høst A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, Christensen AE, Herskind AM, Plesner K. Clinical course of cow’s milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13 Suppl 15:23–28. | ||

Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1172–1177. | ||

Levy Y, Segal N, Garty B, Danon YL. Lessons from the clinical course of IgE-mediated cow milk allergy in Israel. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(7):589–593. | ||

Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(10):902–908. | ||

Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Formula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: a prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):771–777. | ||

Guest JF, Panca M, Ovcinnikova O, Nocerino R. Relative cost-effectiveness of an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:325–336. | ||

Ministry of Health (Brazilian SUS – SIGTAP). Available from: http://sigtap.datasus.gov.br. Accessed February 2015. | ||

Brasindice. Available from: http://www.eln.gov.br. Accessed January 2015. | ||

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/registrocivil/2011/default_pdf_vivos.shtm. Accessed February 2015. | ||

Apps JR, Beattie RM. Cow’s milk allergy in children. BMJ. 2009;339:b2275. | ||

Guest JF, Weidlich D, Mascuñan Díaz JI, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Spain. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:583–591. | ||

Ovcinnikova O, Panca M, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared to an extensively hydrolyzed formula alone or an amino acid formula as first-line dietary management for cow’s milk allergy in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:145–152. | ||

Taylor RR, Sladkevicius E, Panca M, Lack G, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed formula compared to an amino acid formula as first-line treatment for cow milk allergy in the UK. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(3):240–249. | ||

Brazilian Society of Pediatrics, Brazilian Society of Allergy and Immunopathology. [Brazilian Consensus About Food Allergy] Consenso Brasileiro Sobre Alergia Alimentar. Rev Bras alle Imunopatol 2008;31(2):64–89. Portuguese. | ||

Mendonça RB, Franco JM, Cocco RR, de Souza FI, de Oliveira LC, Sarni RO, Solé D. Open oral food challenge in the confirmation of cow’s milk allergy mediated by immunoglobulin E. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2012;40(1):25–30. | ||

Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, et al. Food allergy: a practice parameter update – 2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1016–1025. | ||

Castro AP, Morais MB, Cardoso AL, Vieira MC, Spolidoro JV, Nishikawa AM, Clark OA. Amino acid formula as a first-line diagnosis tool in infants with cow’s milk allergy (CMA): a cost-effectiveness analysis under the Brazilian public healthcare system perspective. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A176. | ||

Morais MB, Spolidoro JV, Vieira MC, Cardoso AL, Clark O, Nishikawa A, Castro AP. Amino acid formula as a new strategy for diagnosing cow’s milk allergy in infants: is it cost-effective? J Med Econ. 2016;6:1–21. | ||

Jirapinyo P, Densupsoontorn N, Kangwanpornsiri C, Wongarn R, Tirapongporn H, Chotipanang K, Phuangphan P. Improved tolerance to a new amino acid-based formula by infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Nutr Clin Pract. Epub 2016 Apr 11. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.