Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 12

Reporting of adverse events related to dietary supplements to a public health center by medical staff: a survey of clinics and pharmacies

Authors Ide K, Yamada H, Kawasaki Y, Noguchi M, Kitagawa M, Chiba T, Kagawa Y, Umegaki K

Received 30 April 2016

Accepted for publication 1 June 2016

Published 12 September 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 1403—1410

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S111749

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Kazuki Ide,1 Hiroshi Yamada,1 Yohei Kawasaki,1 Marika Noguchi,1 Mamoru Kitagawa,1 Tsuyoshi Chiba,2 Yoshiyuki Kagawa,3 Keizo Umegaki2

1Department of Drug Evaluation & Informatics, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka, 2Information Center, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition, Tokyo, 3Department of Clinical Pharmaceutics, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka, Japan

Background: Dietary supplements are used by >50% of the adult population in Japan, and adverse events related to these products have been reported with their increased use. Thus, an efficient system to gather and report data on these adverse events is essential. To date, however, reporting has been limited. The aim of this study was to address this deficiency by exploring the routine reporting practices of the medical staff employed at clinics or pharmacies in Japan.

Methods: We conducted a survey of the procedures used by the medical staff to report adverse events related to dietary supplement intake to public health centers in Japan. The survey was conducted in Japan between November 2015 and January 2016. Based on a sample size calculation, questionnaires were administered to 1,700 potential respondents (850 pharmacists and 850 physicians). The questionnaire inquired about the sociodemographic characteristics and dietary supplement-related adverse event-reporting practices.

Results: The response rate was 34.7%, including 286 pharmacists and 304 physicians. Although >30% of the pharmacists and physicians had prior experience dealing with such adverse events, <5% had reported these to a public health center. The survey identified several barriers to reporting, such as “difficulty judging the relationship between an adverse event and the dietary supplement” and “lack of clarity regarding the severity of an adverse event”.

Conclusion: This is the first study to explore the routine reporting practices of physicians and pharmacists in terms of adverse events related to dietary supplements. Further studies are required to elucidate the severity of these adverse events. Moreover, standard reporting criteria ought to be introduced to improve public health.

Keywords: dietary supplements, complementary medicine, pharmacy practice, government regulations, survey

Introduction

Dietary supplements are used by >50% of the adult population in Japan and the US.1,2 With their increased use, adverse events related to these products have been reported.3–8 Several reports of such adverse events include mortality risks;3,5,6,8 longitudinal cohort studies have suggested a relationship between dietary supplements and mortality.9,10 Hence, causal assessment of adverse events related to dietary supplements is important for prompt regulatory action. Reliable methods for estimating causal relationships between dietary supplements and adverse events have been developed.11 However, before such relationships can be assessed, an efficient means to gather data – such as the MedWatch system established by the US Food and Drug Administration – is essential.12,13

In Japan, there are three main avenues for reporting adverse events related to dietary supplements: 1) manufacturers or retail stores; 2) the practical living information online network system (http://www.kokusen.go.jp/pionet/); and 3) local government public health centers.14 However, manufacturers or retail stores often do not disclose detailed information from consumers, and practical living information online network system reports include limited information, which makes it difficult to identify a cause-and-effect relationship.14 Local government public health centers are the formal points of contact for reporting adverse events related to dietary supplements. However, such reporting is not rigorously enforced, and no formal reporting form has been produced.14 Therefore, the number of cases of adverse events reported is limited; only 20 cases per year were reported between April 2008 and October 2012 according to the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.15 Several barriers to reporting adverse events related to dietary supplements have been reported in other countries.16–18 These include physicians not knowing where and/or how to report adverse events;16 however, there are no similar reports from Japan. To address this issue, it is important to understand the routine reporting practices of the medical staff working in clinics or pharmacies. Hence, we conducted a survey that focused on the habits of the medical staff with respect to reporting adverse events related to dietary supplement intake to public health centers in Japan.

Methods

Study overview

We conducted a survey of clinical pharmacists and physicians aimed at ascertaining their reporting of adverse events related to dietary supplement intake to public health centers. The survey was conducted in Shizuoka Prefecture (Tokai region), Japan, between November 2015 and January 2016. The survey questionnaire included 13 questions with several branch questions (Supplementary materials). The questions pertained to sociodemographic characteristics and dietary supplement-related adverse event-reporting practices. In the survey sheet targeted at physicians, a branch question about their specialty was added. Survey sheets were sent by postal mail to 1,700 potential respondents (850 pharmacists and 850 physicians).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) a pharmacist employed at an insurance agency-approved pharmacy or a physician employed at a clinic; 2) the institution (pharmacy or clinic) was listed in the database of the Tokai-Hokuriku Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare.19 Pharmacists and physicians working at an unlisted pharmacy or clinic were excluded.

Survey contents and procedures

The contents of the survey are shown in Tables 1–3. Briefly, both pharmacists and physicians were asked about their sex, age, work experience, dietary supplement use, and dietary supplement sales in their place of work. The survey also collected data on the number of monthly consultations about the use of dietary supplements; efforts to obtain information; the number of monthly consultations about adverse events related to dietary supplements (if any occurred, questions were asked about how such adverse events were dealt with); whether literature around dietary supplement-related adverse events was reviewed, and the source of any such literature; whether a public health center had been contacted (if not, the reason why); barriers to reporting adverse events to a public health center; and opinions on potentially efficient methods to report adverse events.

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents |

| Table 3 Contacting a public health center |

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Shizuoka (No 27–26; approved on October 5, 2015) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants involved in this study gave their written informed consent before participating in the study.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measure of this study was the rate at which a public health center was contacted about adverse events related to dietary supplement intake. Several secondary outcome measures were also examined. The response rates of the other questions were descriptively analyzed, and the following data were compared between the groups: sale of dietary supplements in the respondent’s place of work, the number of consultations about the use of dietary supplements per month, and the number of monthly consultations about adverse events related to dietary supplements.

Statistical analysis

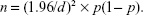

Based on our previous survey,20 we estimated a response rate of 45.3%. We calculated the sample size using this response rate and standard error of the answer to the question from which the primary outcome measure was determined. In this calculation, n denotes sample size, and the probability of the answer chosen is p. The standard error of the answer for each question (d) is thus given by

|

|

In our study, d was set to 0.05. To maximize p (1− p), p was set at 0.5. We thus calculated that a total sample size of 1,700 potential respondents (850 pharmacists and 850 physicians) would suffice to ensure that the standard error of the primary outcome measure was within 5%.

Categorical variables in the survey sheet were expressed as number and percentage, and were compared between the pharmacists and physicians groups using the chi-squared test.21 Statistical significance was set to P<0.05, and all statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.4 for Windows, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. Of the 1,700 potential respondents, 286 pharmacists (49.0% males and 51.0% females) and 304 physicians (88.5% males, 10.9% females, and 0.6% unknown) responded. The majority of pharmacists were aged 30–39 years, while the majority of physicians were aged 60–69 years. The majority of pharmacists had 10–19 years of work experience while the majority of physicians had >20 years of experience. Overall, 156 pharmacists (54.5%) and 81 physicians (26.7%) had used dietary supplements.

Consultations related to dietary supplements

The responses to questions about consultations related to dietary supplements are shown in Table 2. Dietary supplements were sold in 58.0% of the pharmacist–respondent’s stores and in 7.6% of the physician–respondent’s clinics (P<0.0001). Overall, most respondents were consulted about dietary supplements 1–2 times per month (36.0% of pharmacists and 27.0% of physicians; P=0.0126). Over 85% of pharmacists and physicians made no effort to obtain information about dietary supplements (87.1% of pharmacists; 95.1% of physicians). Almost half of the respondents indicated that they had not had any consultations about adverse events related to dietary supplements, while 16.4% of pharmacists and 18.4% of physicians responded that they were consulted 1–2 times per month (P=0.0663). The most frequent means to deal with adverse events in both groups was to recommend stopping the dietary supplement (87.5% of pharmacists and 92.4% of physicians). Only 68.8% of pharmacists and 44.3% of physicians searched the literature for information on adverse events; the details of these literature searches are shown in Table 2.

Contacting a public health center

The replies to questions regarding contacting the public health center are shown in Table 3. Of the respondents who were consulted about adverse events related to dietary supplements, 97.9% (94 of 96) of pharmacists and 98.5% (129 of 131) of physicians did not contact the public health center (P=0.0996). The most frequently cited reason for this was “difficulty judging the relationship between an adverse event and the dietary supplement” among pharmacists, and “the adverse event was not serious enough to report” among physicians. Regarding the question about barriers to reporting adverse events to a public health center, “difficulty judging the relationship between an adverse event and the dietary supplement” and “lack of clarity regarding the severity of an adverse event” were the most frequent responses. The facsimile (fax) was selected by the majority of respondents as an efficient way to report adverse events (66.4% of pharmacists and 63.5% of physicians), followed by telephone and email in both groups.

Discussion

We conducted a survey of clinical pharmacists and physicians regarding their reporting of dietary supplement-related adverse events to a public health center. This is the first study to explore the real-world reporting of such adverse events in Japan. Our data showed that >30% of pharmacists and physicians had experience in dealing with adverse events related to dietary supplements, yet >95% of them did not report them to a public health center. Several barriers to reporting adverse events were also identified.

Dietary supplement sales levels differed significantly between pharmacists and physicians. The number of consultations concerning the use of dietary supplements per month also differed significantly between groups; however, the number of consultations regarding adverse events related to the use of these supplements did not. Thus, pharmacists and physicians were similarly expected to deal with any complications, regardless of whether or not dietary supplements were sold in their establishments. While both pharmacists and physicians were consulted regarding adverse events, >85% of them made no effort to obtain information. This may partly explain the very limited number of adverse events reported to public health centers, and may have led to the oversight of such occurrences. Therefore, a structured or semi-structured system, such as employing MedWatch forms (FDA 3500, 3500A, 3500B) used by the US Food and Drug Administration, is required.12 Incidentally, the rate of occurrence of adverse events related to dietary supplements observed by physicians in Japan may be lower than that observed by physicians in the US, where a survey by Pascale et al revealed that over 70% of physicians encountered adverse events.16 Effort to obtain information may also differ between the two countries.

In terms of dealing with adverse events, the most frequent recommendation by both pharmacists and clinicians was to stop taking the dietary supplement. However, literature searches and proper reporting are important to help other individuals who experience more serious effects when using the same dietary supplements. Proper reporting could prompt official evaluation and appropriate regulatory intervention. Additionally, this information could be made accessible on a public platform such as HF-Net, the information system on safety and effectiveness for health foods.22 This would be helpful to both consumers and health care professionals (including physicians and pharmacists) by enabling them to check dietary supplement safety.

As for communication with a public health center, >95% of pharmacists and physicians who were consulted about dietary supplement-related adverse events did not make contact. The two most cited reasons for not reporting adverse events were difficulty in judging the relationship between the adverse event and the dietary supplement, and the lack of standard reporting criteria outlining the severity of adverse events. Hence, our proposed easy-to-use assessment methods should be helpful for evaluating the relationship between adverse events and dietary supplements.11 As there are no standard reporting criteria regarding the severity of adverse events, such criteria ought to be specified by legislation or public agencies. Several countries already have such criteria;23–27 therefore, the lack of criteria appears to be a crucial problem specific to Japan. Other barriers to reporting adverse events to a public health center were also cited.15 For example, 36% of pharmacists and 35% of physicians selected the answer “Unclear which department is responsible for these adverse events”. By comparison, >60% of respondents to a survey in the US did not know where and/or how to report adverse events, even though there are several systems and structured forms available.12 This suggested that the reporting system is not being used effectively. Hence, in addition to establishing a reporting system for reporting adverse events associated with dietary supplements, it is also important to share information about utilizing such a system.

While we revealed real-world adverse event-reporting practices in Japan, there were several limitations in our study. The main limitation was the lack of detailed information on the adverse events encountered by respondents. This information might provide an indication of how respondents judged an event to be related to a dietary supplement, and how various adverse events were dealt with. These data could also be useful for devising the standard reporting criteria based on the severity of adverse events. Further studies on the details of adverse events are required, for which our own study can serve as a foundation. Another limitation was the possibility of barriers not included in the choices listed in our questionnaires. For example, there may be barriers to gathering information, such as limited staff or time available; such data should be collected and analyzed in future studies.

The limited number of respondents was an additional limitation. We calculated the sample size using the response rate of our previous study and the standard error of our primary outcome measure. However, the overall response rate was 34.7%, which was lower than our estimate. Therefore, the dispersion around the answer to the primary outcome question may be larger than assumed. However, >500 pharmacists and physicians completed and returned the survey. Therefore, our results still ought to be generalizable. Furthermore, this is (to our knowledge) the first report of the routine dietary supplement-related adverse event-reporting habits of pharmacists and physicians in Japan. Therefore, our data ought to provide relevant information in this regard.

Conclusion

Approximately 35% of pharmacists and physicians who responded to the survey had experience dealing with adverse events related to dietary supplements. However, >95% of them did not contact the public health center in this regard. Several barriers to reporting adverse events were identified; however, further studies are required to elucidate the severity of these events. Additionally, adoption of standard reporting criteria would serve to improve our understanding of dietary supplements as related to public health.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participants of this study. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (No 24220501 to HY and KU), and a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (No 15J10190 to KI). The funders had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

KI and Y Kawasaki had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KI, HY, Y Kawasaki, KU, TC, Y Kagawa designed the study. KI, Y Kawasaki, MN, MK acquired the data. KI, Y Kawasaki, MN statistically analyzed the data. KI wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Imai T, Nakamura M, Ando F, Shimokata H. Dietary supplement use by community-living population in Japan: data from the National Institute for Longevity Sciences Longitudinal Study of Aging (NILS-LSA). J Epidemiol. 2006;16(6):249–260. | ||

Garcia-Cazarin ML, Wambogo EA, Regan KS, Davis CD. Dietary supplement research portfolio at the NIH, 2009–2011. J Nutr. 2014;144(4):414–418. | ||

Pittler MH, Schmidt K, Ernst E. Adverse events of herbal food supplements for body weight reduction: systematic review. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):93–111. | ||

Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV, Lin CT. Dietary supplements in a national survey: Prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):1966–1974. | ||

Haller C, Kearney T, Bent S, Ko R, Benowitz N, Olson K. Dietary supplement adverse events: report of a one-year poison center surveillance project. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4(2):84–92. | ||

Patel DN, Low WL, Tan LL, et al. Adverse events associated with the use of complementary medicine and health supplements: an analysis of reports in the Singapore Pharmacovigilance database from 1998 to 2009. Clin Toxicol. 2012;50(6):481–489. | ||

Cohen PA. Hazards of hindsight – monitoring the safety of nutritional supplements. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1277–1280. | ||

Stickel F, Shouval D. Hepatotoxicity of herbal and dietary supplements: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89(6):851–865. | ||

Mursu J, Robien K, Harnack LJ, Park K, Jacobs DR Jr. Dietary supplements and mortality rate in older women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(18):1625–1633. | ||

Michaëlsson K, Melhus H, Warensjö Lemming E, Wolk A, Byberg L. Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f228. | ||

Ide K, Yamada H, Kitagawa M, et al. Methods for estimating causal relationships of adverse events with dietary supplements. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009038. | ||

Kessler DA. Introducing MEDWatch. A new approach to reporting medication and device adverse effects and product problems. JAMA. 1993;269(21):2765–2768. | ||

Getz KA, Stergiopoulos S, Kaitin KI. Evaluating the completeness and accuracy of MedWatch data. Am J Ther. 2014;21(6):442–446. | ||

Umegaki K, Yamada H, Chiba T, Nakanishi T, Sato Y, Fukuyama S. [Information sources for causality assessment of health problems related to health foods and their usefulness]. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2013;54(4):282–289. Japanese. | ||

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/shokuhin/hokenkinou/index.html. Accessed May 25, 2016. | ||

Pascale B, Steele C, Attipoe S, O’Connor FG, Deuster PA. Dietary supplements: Knowledge and adverse event reporting among American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Physicians. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26(2):139–144. | ||

Shaw D, Graeme L, Pierre D, Elizabeth W, Kelvin C. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(3):513–518. | ||

Walji R, Boon H, Barnes J, Welsh S, Austin Z, Baker GR. Reporting natural health product related adverse drug reactions: is it the pharmacist’s responsibility? Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(6):383–391. | ||

Tokai-Hokuriku Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare. Available from: https://kouseikyoku.mhlw.go.jp/tokaihokuriku/gyomu/gyomu/hoken_kikan/shitei.html. Accessed May 25, 2016. | ||

Nakajima Y, Kaneko T, Kintsu M, et al. [Study on the changes in usage of generic drugs in community pharmacies following the 2008 medical treatment fee revisions]. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;40(6):295–302. Japanese. | ||

Plackett RL. Karl Pearson and the chi-squared test. Int Stat Rev. 1983;51(1):59–72. | ||

Information system on safety and effectiveness for health foods. Available from: https://hfnet.nih.go.jp/. Accessed May 25, 2016. | ||

Petroczi A, Taylor G, Naughton DP. Mission impossible? Regulatory and enforcement issues to ensure safety of dietary supplements. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(2):393–402. | ||

Park KS, Kwon O. The state of adverse event reporting and signal generation of dietary supplements in Korea. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;57(1):74–77. | ||

Murty M. Postmarket surveillance of natural health products in Canada: clinical and federal regulatory perspectives. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85(9):952–955. | ||

Kwan D, Boon HS, Hirschkorn K, et al. Exploring consumer and pharmacist views on the professional role of the pharmacist with respect to natural health products: a study of focus groups. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:40. | ||

Gardiner P, Sarma DN, Low Dog T, et al. The state of dietary supplement adverse event reporting in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(10):962–970. |

Supplementary materials

Survey of pharmacists’ and physicians’ dietary supplement-related adverse event reporting practices.

Q1. Are you male or female?

- Male

- Female

Q2. Which age group do you fall into?

- 20–29

- 30–39

- 40–49

- 50–59

- 60–69

- 70–79

- ≥80

Q3-1. For how long have you been working as a pharmacist/physician?

- <1 year

- 1–2 years

- 3–4 years

- 5–9 years

- 10–19 years

- ≥20 years

<Q3-2 is only for physicians>

Q3-2. Which is your specialty? – Multiple choice

- Internal medicine

- Pediatrics

- Obstetrics and gynecology

- Other

Q4. Have you ever used dietary supplements?

- Currently use

- Previously used

- Never used

Q5. Are dietary supplements sold in your clinic/pharmacy?

- Yes

- No

Q6. What is the average number of consultations per month about the use of dietary supplements?

- 0

- <1

- 1–2

- 3–4

- 5–9

- ≥10

Q7. Have you made any effort to obtain information on adverse events related to dietary supplements? – Multiple choice

- Format is prepared

- Standard operating procedure (SOP) is documented

- Other

- No effort made

Q8. What is the average number of consultations per month about adverse events related to dietary supplements?

- 0

- <1

- 1–2

- 3–4

- 5–9

- ≥10

<Q9 to Q11 are for respondents who selected any option other than “0” in Q8>

Q9. How did you deal with the adverse event? – Multiple choice

- Followed up the event

- Recommended stopping the dietary supplement

- Recommended to consult other specialists

- Contacted the manufacturer

- Contacted the consumer information center

- Contacted the consumer affairs agency

- Other

Q10-1. Did you search the literature for information on how to deal with such adverse events?

- Yes

- No

Q10-2. What literature did you use? – Multiple choice

- Natural medicines comprehensive database (NMCD)

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare’s (MHLW) website

- National Institute of Health and Nutrition’s (NIHN) website

- Manufacturer’s website

- Other

Q11-1. Did you report the adverse events to the public health office?

- Yes

- No

Q11-2. The reason why you did NOT report – Multiple choice

- Not severe enough to be reported

- Unable to conclude a causal relationship

- Concluded that the product was not the cause

- Contacted another institution

- Recommended the patients to contact the public health office themselves

- Other

Q12. Are there any barriers to reporting adverse events to the public health center? – Multiple choice

- Unclear which department is responsible for these adverse events

- Unclear what severity of adverse event requires reporting

- Difficult to determine a relationship between the event and supplement

- Difficult to negotiate the reporting system

- Other

Q13. Which do you think are efficient ways to report adverse events? – Multiple choice

- Visit the public health office

- Telephone

- Facsimile (fax)

- Postal mail

- Other

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.